CHAPTER 5

THINKING HOMELAND SECURITY

Theory, Strategy, Decision-Making, Planning, and Analysis Tools

War has been waged against us by stealth and deceit and murder. This nation is peaceful, but fierce when stirred to anger. The conflict was begun on the timing and terms of others. It will end in a way, and at an hour, of our choosing.

President George W. Bush, quoted in the National Security Strategy of the United States, September 2002

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

This chapter is about how choices get made. After 9/11, leaders in the United States at every level of government and the private sector were too busy thinking about securing their parts of the homeland to spend much time considering theories, principles, and constructs. For the most part, they started with what they knew and feared. Threats (see Chapter 3), in large part, determined the character of the U.S. response. Leaders, however, soon had much more to consider. They began with the foundations of America civil society—history and traditions and the strictures of the Constitution (as described in Part 1). Government also built on existing organizations and institutions, albeit reorganizing and refocusing them (see Chapter 4). Leaders in Washington also relied on the instruments used to guide national security during the Cold War. These included developing national strategies to focus the nation’s efforts. The United States has long relied on national strategies to deal with security issues, from World War II to the war on drugs. After 9/11, the Bush administration crafted a family of strategies to guide the global war on terrorism. The National Strategy for Homeland Security of 2002 was perhaps the most important of these documents, providing a framework for how the federal government would organize domestic security activities. These were a start—but not enough.

Dissatisfied by the results achieved with existing strategies, but still believing in the role of strategic assessments, planning, and forecasting in driving public polices, Congress established the requirement for a Quadrennial Homeland Security Review in the Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007. After taking office, President Obama issued new strategies to focus the efforts of his administration.

As the homeland security enterprise developed, it had become clear that a more expansive conceptual tool kit was required—one that enabled leaders to understand current risks and responses better and apply more foresight to future challenges. This chapter addresses key questions faced by the homeland security enterprise and the tools now available to address them. The strategic guidance and methods of analysis, planning, and assessment applicable to homeland security are described and evaluated. These tools apply to international, federal, state, local, and private sector operations, as well as activities that integrate these disparate efforts. They help transform abstract goals into concrete strategies, plans, programs, and budgets.

CHAPTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. Discuss the most significant obstacles to effective management of homeland security activities.

2. Describe which theories have application to homeland security.

3. Explain methods that might be used in homeland security analysis and when they are applicable.

4. Understand challenges to homeland security planning and decision making.

5. Describe the most useful tools for forecasting.

THE CHALLENGES

It is not surprising that the homeland security enterprise has great demand for analytic tools, planning methodologies, and means of strategic assessment. Homeland security encompasses a complex array of activities. The enduring characteristics of this complicated environment include the following.

An Interagency Environment

Effective whole-of-government or interagency operations (where more than one agency or authority combine efforts to address difficult challenges) are essential to successful governance. The United States has a history of both successes and failures in coordinating the activities of major agencies. The national response to the pandemic of 1918 (see Chapter 1), while highly centralized, produced disastrous results, directing policies government-wide that facilitated rather than combated the spread of the disease. In contrast, the Washington-led recovery after the Alaskan earthquake of 1964 (also discussed in Chapter 1) proved a model of effective cooperation.

The capacity of the government to achieve unity of effort is affected by a web of legislative and regulatory guidelines. A case in point is the Economy Act of 1932. This law requires that one federal agency reimburse another for services or goods provided to it. The act was passed to prevent duplication of efforts by government agencies, but it can serve to limit cooperation because one agency can provide support to another only if the recipient has the budget to pay for it. Likewise, the act set limits on the goods and services that can be provided. For example, the Department of Defense cannot provide transportation to other agencies if commercial transportation is available. As a result, during Hurricane Katrina, National Guard aircraft could not be used to transport FEMA personnel to the site of the disaster.

The current interagency system has its roots in the National Security Act of 1947, which reorganized the military departments and U.S. intelligence activities, as well as creating the National Security Council, to address shortfalls in intergovernment cooperation before and during World War II. In the years between World Wars I and II, for example, the U.S. State Department refused to participate in war planning or issue political guidance to Army and Navy planners because it was felt such coordination would be an inappropriate intrusion of the military into the civilian sphere of government. While the system established in 1947 addressed such problems and served well enough during the Cold War, the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security added new challenges to interagency operations.

Interagency activities occur at three levels: policy, operations, and practice. The highest level of interagency activity is policy. At this level, agencies in Washington reach broad agreement on what each will do to support an overall U.S. policy. (The National Security Council, the intelligence community, federal departments, Congress, and other institutions that play major roles in policy are outlined in Chapter 4.)

The intermediate level is operational, where organizations come together to undertake major activities. This is where interagency cooperation often appears weakest. This is a legacy of the Cold War, since federal agencies never needed to do that kind of integrated planning to contain the Soviet Union. Agencies generally agreed on the broad role each would play. There were few requirements under which they planned to work together in the field to accomplish goals under unified direction. After the Cold War, a system was developed under Presidential Decision Directive 56 (PDD–56) which established an interagency process to respond to complex contingencies overseas, such as providing assistance to foreign countries after earthquakes and hurricanes. Agencies chafed under a formal process that required them to define an end state, allocate resources, articulate a plan, and then jointly monitor execution. After a few years, PDD–56 was scrapped. In the wake of 9/11, this level of coordinated government operations has come under criticism on numerous occasions, including the response to Hurricane Katrina (see Chapter 3).

At the lowest level of interagency activity is the practice of cooperation among individuals on the ground. Here too the U.S. government has a mixed record. However, a positive example of interagency operations in practice is the Joint Interagency Task Forces (JIATFs) that direct drug interdictions in the Caribbean and the Western coast of North America. They are a model of effective intelligence sharing and operational coordination, not just for U.S. military and law enforcement agencies, but also for foreign governments. It is not unusual for a French naval vessel to intercept drug runners headed for Europe based on information provided by a JIATF.

The homeland security enterprise encompasses all three levels of government operations. Achieving unity of effort requires establishing cooperation not just at each level, but also in between.

Clash of Cultures

A diverse array of institutions supports the homeland security enterprise. Each has unique attributes that create its organizational culture. These cultures derive from many sources, including the organization’s history and traditions and legal strictures that control its activities. Organizational culture manifests itself in many forms, including jargon (terms and abbreviations used to describe equipment and activity) and the manner of planning and organizing operations. These differences, in turn, can inhibit effective cooperation, serving as a barrier to building trust or contributing to misunderstandings. For example, the Posse Comitatus Act (discussed in Chapter 1), passed in 1878, continues to significantly affect the practice of civil-military relations. Interpreting the law created great confusion during responses to both the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the Los Angeles riots in 1992 (also discussed in Chapter 1). The disputes reflected more than differing legal interpretations. They also demonstrated biases and assumptions based on the cultural perspectives of military and civilian leaders.

Today several forms of “culture clash” are routinely present in the homeland security enterprise and continue to impact efforts to achieve unity of effort.

Emergency responders constitute a diverse group (as described in Chapter 4) with many contrasting cultures. Melding the efforts of responders can be challenging. In the aftermath of a terrorist attack, for example, the police will view the disaster as a crime scene where evidence must be preserved and access controlled. Fire and emergency medical personnel will be primarily concerned with rendering aid. This can cause them to address the same task from different perspectives. While not necessarily a typical example, in at least one major jurisdiction animosity between police and fire personnel has been known to go beyond bureaucratic wrangling to actual disputes at emergency scenes. Such negative dynamics are only exacerbated by unclear policies.

Harmonizing military and civilian cultures can prove a challenge. Civilian federal agencies chafed at the interagency planning process ordered under PDD–56 in part because the methods directed were primarily derived from the military decision-making model. Military jargon and principles can make civilian responders uncomfortable. For example, the military principle of “unity of command,” where all forces serve under a single commander with absolute authority, can chafe civilian responders, such as those from nongovernmental organizations and volunteer groups, who zealously guard their independence.

Relationships among the intelligence community and between the community and nonintelligence organizations have also proved contentious. In order to protect intelligence sources and materials from inadvertent exposure, traditional practices rely on restricting information to those with “a need to know.” After the 9/11 plot went undetected despite the plethora of information available (as described in Chapter 2), a contrasting principle—“the need to share”—was offered up as a means to ensure officials could “connect the dots” and prevent a terrorist attack before it occurred. In industry vernacular, this included the drive to share intelligence found “below the tear line,” referring to the traditional separation in paper intelligence reports between the meat of the report “below the line” and highly-sensitive information about the report’s sources and methods “above the line.” In 2011 debate intensified over the right balance between the intelligence community’s penchant for secrecy and demands for greater sharing of information with the rest of the homeland security enterprise. Huge numbers of classified files on a computer network for sharing by multiple government agencies were stolen and transferred to a foreign website called WikiLeaks, which publicly released them. Disagreements over the role of intelligence, particularly in domestic security, remain contentious.

DHS has struggled to address cultural conflicts within its own ranks. In merging offices and agencies with diverse missions from across the breadth of government, the department has faced the challenge of harmonizing efforts, establishing trust and confidence among subordinate organizations, and instilling a common sense of mission. Establishing the “one face at the border” initiative with Customs and Border Protection (see Chapter 4) was one effort to restructure organizational culture. In 2007 the secretary of homeland security established a task force within the department’s Homeland Security Advisory Council to make recommendations on dealing with internal cultural challenges. The task force concluded that creating a “single” department culture was unrealistic. Instead, it recommended leadership, education, and personnel reforms to facilitate understanding and cooperation among operating agencies.

Different levels of governance can also create challenges. Federal officials and authorities in small communities, major metropolitan areas, states, and territories, as well as tribal leaders, will often come at common problems from different perspectives. Mayors of major metropolitan areas, for example, are responsible for clearly defined jurisdictions and command most of law enforcement resources and responders that maintain safety and security in their cities. They are known to guard jealously their prerogative to manage homeland security–related activities in the communities that elect them. Governors, on the other hand, are responsible for the overall state, with numerous and sometimes overlapping and interdependent jurisdictions, and so may clash with local leaders over priorities, policies, and the allocation of federal assistance such as grants.

Public-private partnerships can be significantly affected by contrasting cultures. Private entities are often reluctant to share data with governments, citing concerns over liability and protecting proprietary information. Furthermore, the American private sector is built on the principle of free enterprise, which holds that government interference in business affairs should be restricted.

Culture clash at the international level is yet another factor in homeland security and a critical one given the importance of cross-border travel, trade, and communication. The United States and the European Union, for example, have contrasting visions on how to best protect individual privacy. This debate is most clearly reflected in continuing disagreements over how to manage Passenger Name Recognition data, the personal identifying information used to check international flight manifests against the Terrorist Watch List (described in Chapter 4).

America’s Culture of Unpreparedness

A culture of preparedness includes both societal norms for preparing before a disaster and behavior after it strikes. Each nation has a unique culture of preparedness that colors how it views the challenges of public safety and disaster preparations and response. This diversity is well illustrated by contrasting U.S. and Japanese responses to disaster. On March 11, 2011, Japan was struck by the fourth-most intense earthquake in recorded history. Following the earthquake, a massive tsunami swept across the country’s northeast coast. With destruction and damage to roads, bridges, ports, railroads, buildings, and other infrastructure, as well as more than 28,000 dead and missing, the disaster impacted more than two dozen prefectures with a population estimated at over 15 million On the whole, the population acted according to pre-established government-organized drills, warnings, and procedures. In the aftermath of the catastrophe, the Japanese people demonstrated remarkable resilience and discipline with no reports of rioting or large-scale disruptions.

Japanese preparedness culture differs significantly from that in the United States. Japan is geographically a much smaller country. When large disasters strike, they tend to impact the nation as a whole. The country has frequent disasters, of uniform character. Everyone in Japan, for example, worries about earthquakes. With many families remaining in the same location for generations, the consequences and responses are shared knowledge in households and local communities. This uniformity makes establishing a common preparedness culture less challenging than in the United States, which is more diverse geographically, in types of disasters, and the makeup of the population.

Research by emergency preparedness experts shows that in the United States, individuals prepare for natural or human-made (technological) disasters only if their experience makes them believe such events might actually affect them. Thus, people in Oklahoma take the threat of tornados seriously, and people in Florida prepare for hurricane season. Yet as the event recedes in memory, preparedness levels decline. For example, in California, as time between major earthquakes lengthens, preparedness levels drop off commensurately. At the same time, U.S. internal migration patterns mean that people raised in an area with one type of disaster threat may move to areas with very different concerns.

The United States does not have a consistent culture of preparedness across the country or even within the same communities. An example of diversity of behavior is the response to major blackouts in New York City. After a power failure in Ontario, Canada, a massive blackout swept through the Northeast on November 9, 1965, plunging the entire city of New York into darkness. Despite the inconvenience, New Yorkers passed the night quietly. In contrast, on July 13, 1977, two lightning strikes caused overloading in the electric power substations of the Con Edison power company, leading to a cascading power failure that spread throughout the New York area. This blackout lasted only one day yet resulted in widespread looting and breakdown of the rule of law throughout many neighborhoods. The contrasting response, even in the same city, demonstrated the great variability in how Americans meet disaster.

These factors, among others, contribute to the complexity of the homeland security environment. As a result, since 9/11 an expanding tool kit has been applied to understanding, managing, and directing the national homeland security enterprise. Some components of this tool kit are described and analyzed in the remainder of the chapter.

THEORIES OF SECURITY

A theory is an intellectual construct or a model used to predict outcomes or describe behavior. Theories are usually thought of as tools for understanding scientific phenomenon, such as Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity concerning the relationship of space and time. Theories, however, are also used to analyze human behavior, comprehend social and political interactions, and predict the impact of strategies and events. Specifically, in the United States, since the dawn of the twentieth century, theories have been increasingly applied to analyze national security challenges.

The utility of such theories is controversial. Some argue there are too many variables for theoretical constructs to make useful predictions or explanations. Theorists contend that while imperfect, their models may be the best or only tools available to explain a particular phenomenon or predict an outcome. Other observers believe theories are valuable mostly because powerful individuals believe in them and shape their behaviors to conform with them. Leaders have preconceptions on how the world should work. Knowing the theories accepted by these people can help explain their motivation, the choices they make, and the outcomes they try to achieve. Understanding the theories behind homeland security is necessary to interpret how strategies, decisions, and plans get made, as well as how decision makers elect to analyze problems.

Two types of theories are prevalent in this arena. One is the “theory of phenomenon,” which purports to represent the nature of activity as it occurs in reality. The other category of theoretical constructs is the “theory of practice,” which seeks to explain the “how” of engaging in an activity rather than explaining the activity’s general nature. Both categories of theory have application to homeland security. There are, however, limits to their usefulness.

In the aftermath of 9/11, there was no unified theory of either the phenomenon or practice of homeland security. Complicating the challenge of “modeling” how to protect the homeland was the dizzying array of activities considered “homeland security” since 9/11, including everything from public safety and public health to immigration and civil defense.

Theories of International Security

Following the September 11 attacks, theories used to address previous national security challenges were applied to homeland security. This included theories of international relations and security and their traditional “schools of thought.” One family of international relations theory is referred to as the Realist School. Realism holds that the international system is basically a collection of states in ceaseless competition. Conflict is inevitable. “Power” is the core concept of this paradigm and the driving objective of states. Conflicts occur because states are constantly striving to ensure national security by maximizing their power in relation to other nations, creating an unending quest for security

A second school of international relations theory is often called “Idealism.” Idealist or “liberal” theories emphasize the “structure” of the environment in which competition takes places rather than just the relative power of nations and their desire for more of it. A structuralist approach to international relations (focusing on how power is exercised and distributed through formal organizations and institutions) holds that conflict and competition are not inevitable. Institutions can act to ameliorate or exacerbate the quest for power and security.

The third general category or “school” of international relations theories is known as “Constructivism.” This paradigm holds that states do not conform to Realist or Idealist patterns of behavior because neither power nor international institutions are most significant in determining behavior. Instead, Constructivist theories contend, nations change behavior depending on their “identity” as determined by both internal and external conditions, including politics, ethnicity, culture, and history.

International relations theories remain helpful in guiding thinking about the homeland security enterprise. For example, the construct known as “democratic peace theory” argues simply that democracies do not go to war with one another. If that is true, then democratic states should be natural allies in battling transnational terrorism. Not surprisingly, after 9/11 the United States quickly looked to forge partnerships with “democratic” allies such as other NATO nations (see Chapter 3), while it was more tentative in embracing countries such as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, which might be helpful but were less than fully democratic.

While theories to describe international relations and security offered some practical use, they also had limits. These theories traditionally focused on the activities of nation states. However, many transnational terrorist groups, such as al-Qaida, were directed by nonstate actors. Additionally, in combating terrorism or providing for disaster response, states needed to ally with international, multinational, and nongovernmental organizations and the private sector. The behavior of these groups may not be adequately accounted for in international relations theories. Further, international security, which focused on interactions between nations, was less useful when looking at domestic security challenges that include actors from local volunteers to “lone wolf” terrorists and a confusing conglomeration of local, state, and federal authorities. Finally, these models had little specific to say about a vast array of homeland security–related activities, from protecting critical infrastructure to safeguarding civil liberties.

Military Conflict Theories

Theories of how conventional wars, insurgencies, and terrorist campaigns are fought have long been a staple of national security decision making. These models emphasize the competitive and interactive nature of armed struggle. Carl von Clausewitz, a Prussian military officer and author of the treatise On War, is perhaps the best known theorist of warfare. Clausewitz offered a “theory of practice” for understanding conflict. He did not provide a prescription on how to ensure victory in war; rather, he stressed how to think about making decisions in war. He emphasized the complexity and unpredictability of warfare, often referred to as the “fog” or “friction” of battle. Clausewitz also stressed the importance of the intuitive judgment of commanders—what he called “genius for war.” Despite writing in the nineteenth century, Clausewitz is still widely cited and debated today.

Contemporary theories of warfare have also been used to understand and deal with terrorist threats. Often discussed, for example, is the work of Cold War theorist John Boyd, an Air Force officer who offered a conception of warfare based on the importance of relative decision making between combatants. His theory of competitive decision making—known as the OODA loop (Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action), Boyd loop, or Boyd cycle—basically holds that the side that acts first wins. Some argue, for example, that terrorist groups, with less decision-making bureaucracy than governments, can act “faster” than states can protect themselves and thus have an inherent advantage. Others, however, disagree that the speed of decision making is the most important factor in a security competition.

Since 9/11 other theories have been cited, including models for battling insurgency and theories of “network-centric warfare” that conceptualize conflict as a battle to protect or degrade networks. For example, some have argued that attacking a terrorist group’s network, including its ability to recruit, fund-raise, and communicate, is more important that targeting individual terrorists.

The virtue of military theories is their emphasis on viewing terrorism as another form of armed competition, a cycle of action and counteraction between those trying to slaughter innocents and those seeking to protect them. Most military theories, however, do not address the underlying motivation of combatants; the “war of ideas” (the struggle between competing ideologies); or other economic, social, or religious factors that influence terrorist threats. Furthermore, these theories have limited utility in addressing issues such as disaster response and civil defense concerns. Many military conflict theories place limited emphasis on “noncombatants,” but this population is central to homeland security activities.

Theories of Public Choice

Another group of theories were borrowed not from models used for national security, but from constructs employed to understand financial, regulatory, and economic decisions. “Public choice theory” involves describing how individuals make decisions in their best interests or the best interest of a group. These theories, first developed to examine economic decision making (how costs and benefits are calculated and acted upon) represent another way of thinking about homeland security that sprang up after 9/11.

Applying public choice theories to homeland security made sense. Many homeland security decisions are made in the absence of information about exactly what a terrorist may do or what natural disaster might strike next. In the face of uncertainties, these theories were applied to determine how to allocate resources and make trade-offs—and, most importantly, determine what part of society should pay for and be responsible for overseeing homeland security measures.

Perhaps the most influential contribution to modern public choice theory was ecologist Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons,” published in the journal Science. Hardin actually began his article with a discussion of a national security issue (nuclear war), suggesting that his theory had applications beyond economic transactions. Hardin’s theory predicts that individuals, acting independently and rationally in accordance with their own self-interest, will ultimately deplete a shared limited resource (such as a common pasture where farm animals graze) even though that outcome is not in their long-term interest. Thus, Hardin argues, “commons” must be protected by a greater authority. Many have used similar arguments for government-imposed homeland security measures to protect “shared” resources such as critical infrastructure.

Writing in the Journal of Law and Economics, economist Ronald Harry Coase offered a conflicting model called the “Problem of Social Cost.” Coase argued that individuals would make the right decision regarding long-term interests and sharing resources if everyone understood all “transaction costs” (the expenses incurred in an economic exchange). For example, if companies fully understood the impact a terrorist attack or natural disaster might have on their businesses, they would take measures to mitigate the risk on their own without regulation from government.

In an influential article in The Atlantic, social scientists George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson discussed another aspect of public choice, their “broken windows theory.” They looked at how governments chose which laws to enforce. Their premise was simple: By enforcing “petty” laws, police can help create a “well-ordered” environment that discourages more serious crime. With great controversy, New York City applied the theory in practice. Former mayor Rudolf Giuliani recalled: “[W]e started paying attention to the things that were being ignored. Aggressive panhandling, the squeegee operators (individuals that would wipe the windshields of passing cars at traffic lights and demand money for the service) … the graffiti, all these things that were deteriorating the city…. It worked because we not only got a big reduction in that, and an improvement in the quality of life, but massive reductions in homicide, and New York City turned from the crime capital of America to the safest large city in the country for five, six years in a row.” Others, however, have questioned the cause-and-effect relationship. “The most sustained attack on broken windows and NYPD achievements has not been practical or factual, but political and ideological,” observed William J. Bratton and Kelling in a 2006 article for National Review Online. “Many social scientists are wedded to the idea that crime is caused by the structural features of a capitalist society—especially economic injustice, racism, and poverty. They assume that true crime reduction can come only as the result of economic reform, redistribution of wealth, and elimination of poverty and racism.” Debates over the cause and effect of public choices continue to rage in regard to homeland security, not only over possible root causes of terrorism, but other controversial concerns, such as enforcing immigration laws.

Determining optimal “public choice” outcomes is central to many hotly debated issues in homeland security, from regulations overseeing critical infrastructure to distribution of security grants. There have been difficulties in applying these theories in practice. Incomplete knowledge, political agendas, the need for secrecy or protecting proprietary information, and other factors can limit the transparency necessary to understand costs and benefits.

Neither public choice, military conflict, international relations, nor other constructs applied to homeland security offer a comprehensive, compelling theory of either phenomenon or practice. Perhaps such theories will emerge in the future. Yet, while current homeland security theories have shortfalls, they still provide frameworks for practitioners who must think through assumptions, preconceptions, and principles to keep America safe, free, and prosperous.

THE WHAT AND WHY OF STRATEGY

Strategies are intended to serve as guidance for the implementation of plans, programs, campaigns, and other activities. In practice, they may serve other purposes as well. Strategies released to the public may also serve political purposes to appeal to certain constituencies, influence public opinion, or intimidate an enemy.

The purpose of strategy is to guide dynamic change in organizations, not direct routine activities. They are used to deal with big complex problems, drive significant change in organizational behavior, or achieve radically different levels of performance. For example, “gaining operational control of the border” can describe a strategic problem. Grappling with this issue involves securing many thousands of miles of varied terrain, from urban centers to rugged desert and hundreds of crossing points. It requires coordinating efforts of multiple agencies and dealing with many challenges, including transnational criminal cartels, human smuggling, and border violence, as well as facilitating the legitimate flow of goods and peoples while enforcing U.S. customs, public health, and immigration laws. On the other hand, a task such as improving the matching of manifests for international flights with the Terrorist Watch List is not usually considered a “strategic” issue, even though the consequences of failure might be very significant. Addressing the efficiency of a particular process or activity is usually about incremental changes that do not require radical transformation such as wholesale reallocation of resources, major reorganization, or drastic policy changes.

Strategies link vision (the endstate being sought, such as “a world without global transnational terrorism”) with specific implementation plans, policies, and programs. The achievement of a vision often outlasts the term of a leader. For example, President Bush had a vision for what “success” would look like in the global war on terrorism, including spreading democracy across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, to help local populations while also denying sanctuaries to terrorists. These were not necessarily conditions to be achieved on his “watch.” Rather, the president established strategic goals requiring numerous interim steps.

The formulation of strategy has broad utility for homeland security. Strategies can be used to guide unity of effort. They can inform the allocation of scarce resources, such as budget dollars and intelligence assets. These are common problems often faced in the homeland security domain.

The most influential strategies are those that make hard choices—allocating limited resources, setting clear bold goals, or establishing priorities. Strategies need not be long, complicated documents. U.S. strategy during World War II, which declared the Allies would “defeat Germany first,” offers a case in point. That simple declarative sentence drove a cascading series of decisions and actions that defined the conduct of the war. Likewise, the simple declaration of a U.S. policy of “containment” defined American policies toward the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War. Thus, there is no single definition of what makes a great strategy other than its ability to mobilize the country in pursuit of a national aim.

The formulation of strategies begins with strategic assessments or evaluations. This is the process of evaluating strategic problems. The first step involves defining the problem (the threat to be overcome), identifying interests (what is important—protecting civil liberties, for example), and the desired end state (what conditions will look like when activities are successfully conducted). This step bounds and scopes the issues that must be addressed in the analysis.

The second step in assessment is to undertake an analysis of the costs and benefits of different options. By their nature, strategic issues tend to address multiple goals at the same time. Border security, which includes enforcing laws, facilitating cross-border trade and travel, and thwarting security threats, is a good example. These goals may often be competing. In other words, facilitating the accomplishment of one goal makes achieving another more difficult. For example, inspecting laptops, hard drives, and memory devices at the border might spot criminal and terrorist activity, but also deter international commerce if companies grew reluctant to expose proprietary information to border inspectors. Assessments allocate relative value to goals and also rate how well different options will achieve a goal. They then use these relative values to determine the best trade-offs. The choice of strategy is determined by considering the importance of each goal and how well proposed responses would achieve them.

Several methods of analysis can be helpful in undertaking a strategic assessment. Key tools are described below.

The objective of a strategic assessment is to help decision makers understand the potential consequences of their choices. For example, a strategy might propose comprehensive and exhaustive physical inspections of all cargo and people to ensure no terrorist threats pass through a point of entry. On the other hand, this strategy might add significant costs and delays that unacceptably diminish tourism and imports.

Strategic assessment is the process of determining how to “pick” a strategy. In turn, the strategy articulates the ends, ways, and means of achieving objectives. The ends define the goals of the strategy. Ways comprise methods employed to achieve the ends. Means describe resources available to accomplish the goals.

Determining the adequacy of strategy is a key task for leaders. One set of criteria often used is the suitability-feasibility-acceptability test. A suitable strategy, if implemented as described, would likely achieve stated objectives. A strategy to secure the border that did not address transnational criminal cartels, for example, would not be suitable. These criminal organizations are one of the chief sources of border violence and human, drug, people, and arms smuggling. A strategy that did not reduce cross-border transnational criminal activity on the U.S.-Mexican border could not successfully impose operational control on the border.

Feasibility is assessing whether the strategy can be implemented. For example, a strategy that cannot be implemented with available resources such as funding is not feasible.

Acceptability measures whether the “stakeholders” affected by the implementation of the strategy consider the course of action appropriate. For example, in the wake of 9/11, Congress passed a resolution supporting the use of military force against those who undertook the attacks on New York and Washington, DC. This act signaled that Congress would accept a strategy involving the use of the armed forces to deal with transnational terrorism.

Crafting American Strategy

National strategies are those that address issues of importance to the nation. They consider how all elements of national power are employed in the pursuit of national objectives, including military force, economic power, diplomacy, intelligence, and law enforcement. These are sometimes referred to as “grand” strategies.

Some national strategies are required by law. Others are prepared at the direction of the president. Strategies can be drafted and coordinated by the National Security Council, or a lead federal agency, such as the Defense or State Department, may be directed to prepare the document. Strategies remain in effect until they are revised or superseded by presidential direction.

National strategies are public documents, designed not only to guide government efforts but also to explain U.S. efforts to American citizens, friendly and allied nations, and potential enemies. Thus, while strategies might not detail everything being done (particularly classified actions, such as spying and secret operations), they do outline future efforts.

Strategy and Homeland Security

National strategies are particularly important to the task of homeland security. While defending the homeland is not new, merging the many activities of that task into a holistic mission is revolutionary. Likewise, determining how to set priorities, organize activities, and measure successes is an unprecedented challenge. Obtaining national unity requires the guiding vision of national strategies. Homeland security activities are guided by a number of overarching strategies. In the wake of the September 11 attacks, eight new strategies were published; five were specifically developed for combating terrorism, while the others were revisions of earlier strategies to account for dangers of the post–9/11 world.

NATIONAL STRATEGIES

The national strategies comprise both offensive and defensive measures. Strategies prepared by the Bush administration for national security, combating terrorism, controling weapons of mass destruction, and using the military were primarily focused on defeating terrorists overseas. The national homeland security strategy and strategies for critical infrastructure protection and cybersecurity centered on the homeland. Strategies relating to drug control policy and money laundering dealt with transnational criminal activities in which terrorists might also engage.

The national security strategy, required by law, provides a broad framework for how all instruments of national power will be employed, including the military, intelligence, diplomacy, and law enforcement. President Reagan issued the first public national security strategy in 1988. President Bush issued the first version of his strategy in September 2002, which included a specific section related to global terrorism.1

Prior to 9/11, combating transnational terrorism was primarily considered a law enforcement activity. The new strategy shifted the priority from arrest and prosecution to preventing attacks and killing or capturing terrorists.

In 2010 President Obama released his national security strategy. The president continued to make defeating transnational terrorism a pillar of American strategy. While there were distinct differences in tone, there were also significant continuities, despite the first post–9/11 shift in the political party affiliation of the presidency. Obama’s published strategy, for example, included a section titled “Disrupt, Dismantle, and Defeat Al-Qa’ida and Its Violent Extremist Affiliates in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Around the World.”

One significant difference between strategies offered by the first two post–9/11 presidents was President Obama’s decision to merge concepts of national security and homeland security more closely. The strategy, Obama contended, complemented “our efforts to integrate homeland security with national security, including seamless coordination among Federal, state, and local governments to prevent, protect against, and respond to threats and natural disasters.”2

ASSESSING THE NATIONAL STRATEGIES

There is little question that national strategies provide a comprehensive and nested set of guidelines. But it may require years of implementation before it can be determined whether they are effective.

Evaluating the national strategies will likely fall into two areas. The first concerns the sufficiency of the strategies—whether they contain adequate guidance to direct purposeful national policies and programs. The second area that will bear examination is the capacity of the strategies to reduce the threat of global terrorism and enhance homeland security. On the second point, the success of the strategies will turn on their underlying assumptions. While strategies can be modified and updated as lessons are learned, strategies based on faulty premises are unlikely to prove effective.

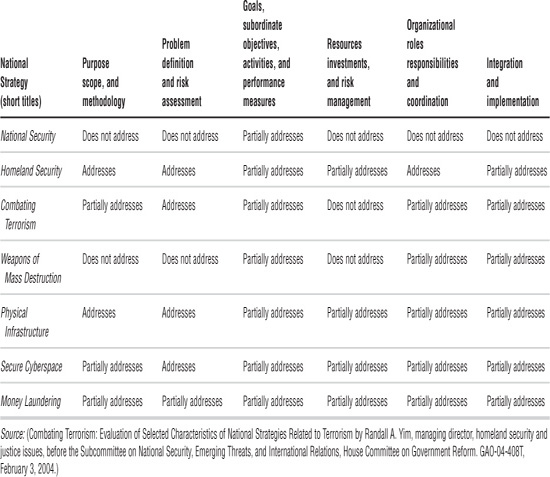

The Fundamentals of Strategy

There is no universal agreement on the necessary components of strategy for describing ends, ways, and means. An analysis of the national strategies by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) in 2004 listed several useful criteria. The characteristics the GAO identified are (1) purpose, scope, and methodology; (2) problem definition and risk assessment; (3) goals, subordinate objectives, activities, and performance measures; (4) resources, investments, and risk management; (5) organizational roles, responsibilities, and coordination; and (6) integration and implementation. At the time GAO (now called the Government Accountability Office) determined that U.S. strategies were generally good at establishing the purpose, scope, definition of the problem, and overall goals. The GAO, however, determined that none of the strategies addressed all elements of resources, investments, and risk management or integration and implementation.3

Questioning Assumptions

Another means for evaluating strategies is to examine their underlying premises. By questioning such assumptions, one can evaluate whether a strategy has correctly diagnosed the nature of the problem and proposed adequate solutions. There are several issues that an assessment of the national strategies might explore.

FIGURE 5.1

National strategies and the extent they address GAO’s desirable characteristics

Offense versus Defense

One key debate is whether to emphasize offense or defense. Rethinking that balance in the light of emerging threats remains a priority. Cold War strategy relied on deterrence. New strategies look to employ a mix of deterrence, preemption, retaliation, and homeland security. What constitutes the best balance and what defenses best complement offensive measures are open to debate. For example, some defenses might better enable offense, allowing the United States to apply diplomatic, economic, or military means abroad without fear that an enemy could retaliate on the homeland. An optimum homeland security system would enhance freedom of action and be facile enough to deal with threats not easily countered by taking the battle to the enemy.

President Bush’s national security strategy was built on the assumption that the best defense is a good offense. The first priority of the strategy with regard to terrorism was disrupting and destroying terrorist organizations with global reach. Specific targets include leadership, means of communication, and control of terrorist cells, financing sources, and material support. In contrast, while President Obama’s strategy did not preclude offensive action, his strategy emphasized the importance of exercising restraint in the use of force.

Layered Defense

The homeland security strategy and its supporting directives assume a layered approach to America’s security system. This approach offers both advantages and disadvantages. One advantage of multiple layers of security is that they increase the challenges facing terrorists. In addition, the redundancies provide multiple defenses that mitigate the requirement for each and every system to function flawlessly. A disadvantage of multiple measures is the expenseof maintaining and coordinating numerous disparate security systems. Additionally, it may be unclear how much protection is achieved through layered security until all the systems supporting them are up and running.

War of Ideas

Another controversial component of national strategy is how to wage a “war of ideas.” The Bush strategy emphasized this goal, calling for a campaign to make clear that acts of terrorism are illegitimate and diminish underlying conditions that support terrorism by promoting democratic values and economic freedom.

The administration argued that reducing global terrorism requires addressing problems in the developing world, including lack of good governance and poor economic growth. While there are many failed and failing states, however, not all have proved to be midwives for transnational terrorist threats. In addition, many of the world’s most notorious terrorist leaders are well educated and from families of some means. Some security analysts doubt a strong nexus between transnational threats and weak states. Others argue that even if such a connection can be made, the United States can only tangentially affect developments in these countries. In short, they argue the United States cannot conduct an effective war of ideas.

In contrast to the emphasis placed on the “war of ideas” by the Bush administration, the national strategy authored by President Obama made little mention of combating extremist ideology. Rather, Obama emphasized engagement and partnership with key Islamic nations.

Sufficient Strategies

One subject for debate is whether current strategies sufficiently address critical mission areas in homeland security. For example, maritime, border, and transportation security are interrelated, complex missions. While each element is addressed in various defensive strategies, it is not clear they comprise a holistic solution. Another area of concern is the connection between terrorism and transnational crime. Although the national drug policy and money-laundering strategies address these problems, terrorists also use other types of crimes, including identity theft, insurance fraud, and human smuggling.

Adequacy of Resources

Federal spending on homeland security more than doubled after the 9/11 attacks. The Bush administration’s strategy for homeland security, however, did not envision substantial further increases in federal spending. The strategy’s stated preference was to rely on the principles of federalism and cost sharing between the public and private sectors. This approach may not be sufficient to ensure adequate participation by cash-strapped state and local governments, as well as by a private sector reluctant to invest in improvements to protect critical infrastructure, particularly following the economic recession from 2007–9. After taking office in 2009, President Obama emphasized the importance of restraining security spending.

STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT

Strategy is meaningless without means to turn aspirations into action. This task requires drafting plans, programs, and policies for effective implementation. Guiding implementation of homeland security activities can be particularly challenging in light of the numerous stakeholders involved, the many threats that must be considered, competing priorities, and innumerable “culture” clashes to be overcome. Key elements of the task are deliberate decision making, crisis action decision making, and planning. They are described below.

Deliberate Decision making

This is the process by which leaders make deliberate choices for establishing and implementing policies and programs. Decision making has an impact on every aspect of homeland security, from budgeting to personnel management to overseeing operational activities, such as conducting border security.

Deliberate decision making is appropriate when there is the time, information, and other resources required to analyze and make decisions. Some formal decision-making processes, such as issuing federal contracts, are governed by laws and regulations, in this case the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). The FAR provides rules for government agencies in purchasing goods and services. Federal agencies supplement these rules with their own departmental acquisition regulations. Other laws and regulations guide personnel, budgeting, and operational activities. The Stafford Act, for example, bounds how federal agencies can respond in supporting state and local governments during emergencies.

Some homeland security decision-making processes have been established by policy. A good example is the National Terrorism Advisory System, established in 2011. DHS established a formal process for determining when advisories are appropriate, the format for issuing them, and the duration of their effectiveness. Each president also establishes formal procedures through which policies are coordinated, adjudicated, and reviewed by the National Security Council.

There is no standard means for undertaking deliberate decision-making. Components of this process usually include (1) an analysis of the task to understand all stated and implied subtasks required, as well as all internal and external factors (budget, etc.) that impact the accomplishment of the task; (2) development of alternative, distinct, and feasible courses of actions or policies that might accomplish the task; (3) an evaluation and comparison of alternatives to determine their advantages, disadvantages, and relative utility in accomplishing the task; and (4) making a decision—selecting a course of action or policy.

The challenges of deliberate decision making for homeland security are many, including coordinating decisions. Homeland security activities are bound by directions of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. In the case of DHS, for example, multiple congressional committees and subcommittees have jurisdiction over the department. In performing their oversight, they can issue contradictory guidance that complicates the department’s efforts to establish priorities. Even inside the executive branch, coordination of programs and policies within the bureaucracy can be time consuming and difficult. For example, after DHS concluded the Homeland Security Advisory System should be replaced by the National Terrorist Threat Advisory System, it took a year to vet the decision with other federal agencies and obtain presidential approval. Similar challenges may be faced at every level of government.

Crisis-Action Decision Making

This decision-making process differs when limited time and information are available, yet there is an urgent imperative. By its nature, homeland security often deals with unexpected and grave threats and will require crisis-action decision making.

As with deliberate decision making, there is no uniform process for managing crisis-action decisions. The homeland security enterprise does include structures such as emergency operations centers, organized to provide information and support to facilitate crisis decisions. The United States also relies on the Incident Command System to provide an organizational structure to manage disaster response. These institutions, however, do not dictate how crisis decisions get made, nor are they universally applicable to every challenge.

Leadership in a crisis consists of several steps. The first is recognizing a “crisis” and the nature of the challenge to be overcome. This is not a trivial step. During World War I, for example, the U.S. government was slow to recognize the threat of a deadly pandemic influenza outbreak (described in Chapter 1). When Washington did identify the problem, it misperceived the most important objectives in the response, emphasizing rushing U.S. troops overseas rather than stopping the spread of the contagion. In the end, crisis decisions made by Washington actually made the situation worse.

The second step in a crisis is selecting and implementing a course of action. Unlike with deliberate decision making, in a crisis there is limited time for analysis, study, and consideration of alternative courses of action. Thus, it is usually only feasible to consider and refine a single means to address the crisis. In some cases, decision makers can rely on contingency plans, which are developed beforehand to deal with anticipated emergencies. Often, however, conditions may not be exactly the same as anticipated, and contingency plans must be modified. The 2010 Gulf oil spill offers a case in point. National plans for responding to spills of significant size anticipated they would be similar to the 1989 Alaska oil spill from the Exxon Valdez tanker. The spill in the Gulf of Mexico, however, proved a very different challenge, covering a much larger geographical area and the jurisdiction of several states. Thus, existing plans proved inappropriate. In other cases, such as the attacks on 9/11, no applicable contingency plans may be available. Under these circumstances leaders must rely on expert judgment and limited assessments to develop a course of action.

The third vital step in crisis-action decision making is communicating decisions and risks. While consulting with stakeholders and explaining decisions to the public and the press are also part of deliberate decision making, with critical and independent tasks during a crisis, when the consequences of misperception and misunderstanding can be far graver. Failing to communicate effectively and rapidly can undermine the legitimacy of decision makers and put people at risk. For instance, in 2004 the Spanish government rushed to attribute devastating train bombings in Madrid to a domestic terrorist group. When it was later determined the attack was perpetrated by a transnational Islamist organization, the government was severely criticized and the ruling party driven from power. Another example of poor communications during a crisis occurred in the 2011 nuclear incident after the earthquake and subsequent tsunami in Japan. The Japanese government’s inability to provide satisfactory information regarding the conditions at the Fukushima nuclear plant exacerbated fear and uncertainty among Japanese citizens and led to speculation and misinformation in news reports around the globe.

The fourth step in crisis-action decision making is making a determination that the crisis is over and transitioning back to deliberate means to oversee operations and activities. The most difficult aspect of termination often involves public reflection on the crisis, such as determining responsibilities for failure and the adequacy of the response.

Planning

Planning is formalized procedures that result in executing an integrated system of decisions. Planning processes are formal for the same reason that chefs write down recipes—to make sure nothing gets left and the results have a uniform character. Establishing a framework to ensure that decisions are explicit and integrated is necessary to produce predictable results. Plans distinguish what tasks must be done, who should do them, in what sequence they should be performed, and what coordination is required.

Homeland security planning can be used to implement both deliberate and crisis-action decisions. Planning is a tool for developing plans, policies, directives, standard operating procedures, regulations, and other guiding documents that direct how activities will be conducted. Plans are useful to ensure the accomplishment of tasks, facilitate unity of effort, and increase collaboration, understanding, and trust between organizations participating in the process.

Fundamental elements of the planning process are (1) establishing a planning team; (2) analyzing information and understanding the situation; (3) determining goals and objectives; (4) developing a “concept of operations,” a conceptual explanation of how the goals and objectives will be achieved; (5) writing the plan; (6) coordinating, validating, refining, and disseminating the plan; (7) training, exercising, testing, and evaluating the plan’s effectiveness; and (8) reviewing, revising, and updating the plan.

As of 2011, there was no standard planning process for homeland security at any level of government or within the Department of Homeland Security, though a number of plans had been established, including ones for distributing aerosolized anthrax medical countermeasures, responding to a pandemic influenza outbreak, and dealing with mass maritime migration. FEMA has also developed contingency plans for some regions for a variety of incidents, from mitigating the terrorist use of explosives to responding to winter storms.

Within DHS, planning functions are distributed among several entities. The secretary sets priorities and direction for overall strategic planning efforts. The secretary chairs a senior leadership group, which includes heads of all department components. This group acts as an advisory body to the secretary. The Office of Policy is responsible for developing strategic guidance. The Directorate of Management oversees resource allocation (including managing the department’s budget). The Office of Operations Coordination and Planning integrates various internal plans developed by components of the department. Furthermore, each operational and support component develops its own plans to guide its activities. Finally, the department’s Office of General Counsel, the Privacy Office, and the Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties review plans and policies to ensure they comply with laws and regulations.

There are many pitfalls to effective homeland security planning. These include the following.

• Leaders not engaged in the planning process. All too often leaders become engrossed in day-to-day activities and either neglect planning activities, fail to provide adequate resources, or delegate planning to subordinate staff. Plans that lack the input or commitment of senior leaders are more difficult to implement.

• Failing to integrate planning and managing an organization. Many organizations produce “shelfware” plans, documents stuck on a shelf and ignored because the process of comprehensive planning was not fully integrated into how the organization is actually run.

• Missing appropriate metrics to evaluate adequacy of planning. The evaluation of plans requires “feedback” to determine whether the guidance provided is actually leading toward the accomplishment of goals. This feedback may come in many forms, including tests, exercises, and evaluations of performance.

• Balancing formal and adaptive planning. Plans are useless if they do not conform to conditions “on the ground.” There is always tension between the requirement to establish routinized and structured plans and the need to modify planning processes to meet changing situations.

• Lack of community involvement. Many emergency plans are developed without direct involvement from the community. As a result, people tend to have little faith that these plans offer the best courses of action to protect them and their families. On the other hand, disaster planning that includes input from the community produces not only better plans but also far higher levels of community approval and confidence.

Even if these and the myriad of other challenges can be overcome, successful planning does not by itself ensure effective execution of the plan. A chief of the Prussian military staff once remarked that “no plan survives contact with the enemy.” In other words, it is unlikely that planners can anticipate and account for all conditions and variables that might thwart the smooth implementation of the plan. However, as General Dwight D. Eisenhower once remarked, “Plans are nothing, but planning is everything.” A good plan provides a guiding idea from which organizations can adapt. Planning is fundamental to the homeland security enterprise.

ANALYTICAL TOOLS

Analytical methods have utility for all tasks related to “thinking” security, from applying theory to conducting strategic assessments to decision making and detailed planning. Many analytical tools are suitable for the difficult and complex challenges of homeland security, from dealing with present problems to forecasting future needs.

No single method of analysis is suitable for every problem. Some issues that confront leaders and managers have a “linear” character. In other words, they involve processes or activities that can be defined by specific cause-and-effect relationships, where changing conditions, variables, inputs, and outputs produces predictable affects. For example, managing the Terrorist Watch List is mostly a linear activity. Each step in the process can be mapped and measured. When specific changes are made to how the list is collected, correlated, and disseminated, they can be evaluated. In contrast, other activities related to homeland security are nonlinear. These are often called “wicked problems.” A characteristic of nonlinear activity is that the effect of changes cannot be predicted easily because it is difficult to understand how they will alter the overall activity. This is especially true when those affected by the change are able to alter their behavior in response. An example of a more complex problem might be terrorist travel. While changes to the Terrorist Watch List may be made with predictable affects (for example, making the distribution of the list more efficient), predicting how those modifications might impact terrorist efforts to infiltrate the United States might be more difficult. There are many variables in terrorist travel. These may or may not be affected at all by changing Terrorist Watch List procedures. The problem for accounting for all of the decisions and choices the terrorists might make is nonlinear.

The first task in applying analytical tools to homeland security is to understand the nature of the problem. Some methods of analysis are more appropriate for linear analysis. Others are better suited to understanding complex, nonlinear systems. Sometimes methods are combined.

Deciding which tools to apply is also influenced by the nature of the research question, the kind and amount of data available for analysis, and the optimum research method to yield results that adequately address the research question. All three of these elements are essential to crafting an effective analysis. The research methods described below provide a spectrum of tools to address a range of questions and data sets.

Complex Systems Analysis

Many problems faced by policymakers today involve trying to understand, predict, or affect the behavior of complex systems. Yet policy makers rarely comprehend the full impact their decisions have on the behavior of these systems. Rather than deal with systems as a whole, contemporary decision makers tend to concentrate their choices on discrete activities that are easier to identify and understand. The problem is that the more complex and disorganized the system, the more unpredictable the outcomes of discrete, uninformed intuitive decisions by policy makers. Failing to understand how discrete decisions impact the system as a whole can produce unintended and counterproductive consequences. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, for example, emergency officials barred all but authorized emergency responders from entering New Orleans. As a result, fuel handlers, who had not been credentialed by officials, could not make deliveries to emergency operations centers that were powered by generators. Without gas or fresh batteries, the centers lost power and became inoperable. Officials failed to understand how the entire system worked. They fixed one problem—preventing unnecessary convergence at the disaster scene—but they also created another—preventing resupply of key command and control nodes.

Describing complex systems—how they work and how the systems’ performance can be changed—is the task of complex systems analysis. There is no single means to undertake the study of complex systems. Often mathematical models or visualization maps are developed to interpret system behavior.

Operations Research

Rather than focusing on the performance of a system as a whole, operations research entails focusing narrowly and in greater depth on a single process or organizational activity. In short, it conducts an end-to-end assessment of how specific tasks or missions are performed. Operations research is a means of evaluating linear activities to determine the most efficient means to improve or disrupt a process. Conducting effective operations research normally requires comprehensive, complete, and reliable data on the activity being studied.

Risk assessment and risk mitigation are common tools often used in evaluating homeland security activities. There are, however, many other techniques and tools. Operations research can employ a diversity of techniques, from surveys and direct observation to computer analysis. Simulations are used to test different options and evaluate ideas for improvement. Optimization analysis determines trade-offs and which options offer the best balance of costs and benefits. Statistical analysis tests and predicts outcomes. While operations research is not new, information age capabilities (the ability to gather and sort vast amounts of data) have greatly expanded its potential to improve homeland security decision making.

The Delphi Technique

Seeking the judgment of experts is a common method of assessing the efficacy of current activities or anticipating future problems. However, experts often give conflicting advice. In part, this is because their advice is often “unstructured,” provided different forms on various topics focused more on the experts’ knowledge and interest than the questions analysts are interested in answering. Unstructured queries of experts can also leave unchallenged their individual assumptions and prejudices. The Delphi technique, developed by the RAND Corp., is designed to provide a richer and more structured process for drawing on expert judgment. This process, though, can require significant time and resources.

The method engages many experts in formal process to produce a comprehensive estimate of “future” states. While this method of analysis depends heavily on experts’ intuition and judgment, it tests their ideas against others through an iterative process using a questionnaire. First a questionnaire is developed and submitted to a panel of experts. The results are analyzed, and the mean responses are returned to the panel with a second-round refined questionnaire. This process is repeated until clear points of convergence or disagreement are identified. The questionnaire process is superior to the traditional peer-review process because it limits the influence of strong personalities and views.

Horizon Scanning

This method of analysis has been referred to as “looking for black swans.” Horizon scanning seeks opinions, analysis, views, or data that dramatically diverge from expected trends—expert judgments that diverge from commonly held views with unique predictions. Point of horizon scanning recognizes that black swans are out there and are going to appear. When they do, they seem to be a surprise, but only because they are unexpected, not because they were unlikely. The purpose of horizon scanning is to forecast trends that might happen or be happening, but are not being noticed.

Fundamentally, horizon scanning is about analyzing an amount of data in a systematic manner and picking out anomalies. A common horizon-scanning technique is the structured oral interview, which includes a diverse group of experts in different fields. Other techniques rely on accumulating data to look for irregularities in current trends, sometimes called “weak signals” of emergent patterns or activities.

Scenario-based Planning

Most future forecasting is linear. In other words, analysts look at present conditions and try to predict if they will get worse or better—if, for example, there will be more or fewer transnational terrorist attacks. This is called trend analysis. The attacks on 9/11 were not predicted by many analysts because they departed so radically from contemporary terrorist trends. These are called “shocks,” which may simply represent discernible trends that went unrecognized. For example, al-Qaida had stated its intentions of attacking America and launched strikes against U.S. targets before 9/11. On the other hand, shocks may represent true discontinuities.

Scenario-based planning is an alternative method for forecasting future requirements. It provides a means to combat the tendency to plan against only the most anticipated end state. In scenario-based planning, analysts postulate alternative future conditions and determine the optimum response for each. They then analyze the capabilities needed to provide that response and determine how to obtain those capabilities. Finally, they compare the results of each analysis and identify common capabilities and responses across the scenarios.

Common capabilities identified by the analysis form the basis for future contingency planning, offering a core set of responses that would likely be highly useful regardless of how the future unfolds. Scenario-based planning may also identify unique capabilities required to meet specific contingencies. This method also holds the advantage of providing a structured, common framework for problem solving and planning.

Net Assessment

Another problem often found in forecasting, and the way that Washington makes decisions regarding homeland security, is that the urgent often crowds out the important. Leaders distracted by the pressures of daily meetings, briefings, and decisions often fail to anticipate the long-term consequences of their decisions. The free-thinking, speculative nature of net assessment offers senior leaders a disciplined process to expand their thinking horizon beyond the immediate environment and timeframe. This process begins with a premise—many homeland security challenges are a series of actions and counteractions between competitors—and asks how these competitions might progress in the future. Net assessment argues for a comprehensive approach to analysis, looking at the full range of factors that shape and alter the security environment of the future, including social, political, technological, and economic trends.

The net assessment method employs diverse tools for understanding the nature of competition. The net assessment process often begins with systems analysis and game theory to interpret competitive environments. It adds to these analytical methods by helping to produce predictable outcomes, such as computer modeling that posits the impact of changing oil prices on consumer goods following a terrorist attack on pipelines. This process encourages leaders to consider unexpected outcomes that emerge from unforeseen and unappreciated factors. In the end, net assessment takes on multiple complexities and forecasts futures that conventional analyses or formal models may overlook. A net assessment will not predict the future but can help analysts appreciate future outcomes they might confront.

Red Teaming

Examining a competition from an adversary’s perspective, or “red teaming,” is a common technique used either as part of a net assessment or as independent analysis. The method of analysis is also called “adversary-based assessment.” The goal of the red team is to provide a fuller understanding of an adversary’s options and potential actions. Its task is to propose technically feasible and responsive threats. Red teams challenge assumptions, expose vulnerabilities, and identify unappreciated risks or opportunities.

A number of different techniques are used for this type of analysis. Red teams can play the role of surrogate adversaries. They emulate an enemy, offering counters to each action taken against them, or actually conduct operations, such as penetrating security at sensitive facilities, to identify vulnerabilities. Individuals or teams can act as “devil’s advocates,” who offer critiques or alternatives to strategies, policies, or plans. They might, for example, be given the same intelligence as that provided to decision makers, offering alternative conclusions or assessments of enemies’ intentions. A third category of red teaming is the use of advisory boards or outside experts who offer alternative judgments.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Homeland security is about making hard choices, which in many cases are only getting harder in an era of budgetary limitations and competing priorities. In managing the homeland security enterprise, leaders and their support staffs have many tools available, from conceptual frameworks provided by theory to detailed methods for analyzing problems and drafting complex plans. All these instruments for “thinking” homeland security have both strengths and weaknesses. Understanding what they can and cannot do, the challenges to utilizing them, and how to apply them is one of the most significant challenges in the homeland security enterprise.

CHAPTER QUIZ

1. What is meant by the term war of ideas, and why is it important to U.S. strategy?

2. What does the concept of layered defense mean?

3. What do decisionmakers do when they lack necessary information to make a decision?

4. Why is there not a single theory of homeland security?

5. How, and how much, did the strategies of Presidents Bush and Obama differ?

NOTES

1. PL 107–296 § 2(6).

2. National Security Strategy of the United States (May 2010), http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_strategy.pdf, 2.

3. U.S. General Accounting Office, “Combating Terrorism: Evaluation of Selected Characteristics in National Strategies Related to Terrorism,” GAO–04–408T (February 3, 2004).