CHAPTER 11

THE TRANSNATIONAL DIMENSIONS OF TERRORISM

From State Sponsors to Islamist Extremists

The past two years have highlighted the growing breadth of terrorism faced by the United States and our allies. Although we and our partners have made enormous strides in reducing some terrorist threats—most particularly in reducing the threat of a complex, catastrophic attack by al-Qa’ida’s senior leadership in Pakistan—we continue to face a variety of threats from other corners … While these newer forms of threats are less likely to be of the same magnitude as the tragedy this nation suffered in September 2001, their breadth and simplicity make our work all the more difficult.

Statement of Michael E. Leiter, (then) Director of the National Counterterrorism Center, February 9, 2011

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

International and transnational terrorism concern the United States in several ways. Most obvious and important are direct attacks against the U.S. homeland and American citizens abroad. But homeland security must also address terrorist groups that organize and raise funds in the United States to support violent acts against U.S. allies and innocent civilians around the world. The capabilities of international terrorist groups have been enhanced in many cases by the assistance of foreign governments, known as state sponsors of terrorism.

Along with global terrorist networks and sponsors, transnational criminal organizations pose a threat to U.S. security, especially when they cooperate with terrorist groups that exploit the trade in illegal drugs, a phenomenon known as narco-terrorism. This both increases the supply of drugs in America and destabilizes U.S. allies.

Finally, despite success in weakening the main branch of al-Qaida, known as al-Qaida Core or Central, in the years after 9/11, the United States must also remain extraordinarily vigilant against Islamist-inspired terrorist groups. For decades, these groups have singled out the U.S. and its allies for attack. Al-Qaida planned to follow up the 9/11 attack and related groups, such as al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula and the Pakistani Taliban, have now taken up that objective. They have also enlisted a relatively small but significant number of American citizens in their cause since 9/11.

This chapter surveys transnational terrorist trends, including those related to criminal activities and Islamist extremism. The chapter provides a framework for understanding the contemporary nature of transnational terrorism and how it evolved.

CHAPTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. Define transnational terrorism.

2. Describe the beliefs and motives of radical Islamist groups.

3. Identify major international terrorist groups operating in the United States and their objectives.

4. Explain the concept and dimensions of narco-terrorism.

5. Identify terrorist state sponsors and trends in their support of international terrorism.

AMERICA IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD

When President George Washington urged the young nation to avoid foreign entanglements in his 1796 farewell address, he could hardly have imagined the complexity of America’s current relationship with the world. Connected to other countries by technology, economics, travel, news media, diplomacy, security, and vast numbers of immigrants from an array of ethnic and religious backgrounds, the United States is linked inextricably to virtually every corner of the planet. This phenomenon is often called globalization.

DEFINING TRANSNATIONAL TERRORISM

Under the U.S. legal definition, transnational, or international, terrorism occurs primarily outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States or transcends national boundaries by its means, the people it intends to terrorize, or the location in which the terrorists operate or seek asylum. International terrorist groups can also be defined as those whose leadership and personnel are mostly foreign and whose motives are primarily nationalist, ideological, or religious.

Modern History of Transnational Terrorism against the United States

As holiday travelers dashed through New York’s La Guardia Airport on the evening of December 29, 1975, thoughts of upcoming New Year’s Eve celebrations disappeared with an enormous explosion. “A bright blue flash. A blast of air. Deafening noise. Broken glass rained down,” described one account. The impact was so strong one survivor thought a plane had crashed into the terminal, but the actual cause was a time bomb in a coin-operated storage locker. The device killed 11 people and wounded more than 70. Survivors saw bodies, body parts, and blood strewn across the airport, but there was no immediate screaming, reported one observer: “It seemed like everyone was in shock. The whole thing was just a complete wreck, with mobs of people just standing around. You can’t believe it until you see something like this.”1

The blast prompted a massive investigation. But in 1975 there were so many terrorist groups with the capabilities and intent to target the United States that the police faced a daunting task. Domestic groups such as left-wing extremists and the Jewish Defense League came under suspicion. The FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional, or Armed Forces of National Liberation), a Cuban-backed Puerto Rican independence group, had detonated a deadly bomb in a New York tavern less than a year before and appeared a potential suspect.

There was also an extensive roster of international terrorists to consider. U.S. citizens abroad had recently been targeted by Communist ideological terrorists from Germany and Japan, among others, and a variety of Middle Eastern groups. While not believed likely to attack the United States, Irish Republican Army (IRA) operatives were known for their devastating bombings in Great Britain and support of activities in New York and elsewhere in the United States. Investigators considered the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which quickly denied involvement. Then, in September 1976, Croatian nationalist terrorists, seeking independence from Yugoslavia, hijacked a TWA jet leaving La Guardia. They also left a bomb in a coin-operated locker at New York’s Grand Central Station. It went off while being dismantled, killing one police officer and badly wounding another. Despite differences in the airport and train station bombs and denials from the captured hijackers, officials continued to suspect the Croatians of involvement in the La Guardia blast. The crime was never solved.

One lesson, however, was clear: U.S. citizens at home and abroad were at risk from international terrorist groups with a vast range of ideologies but one common belief—that attacking American targets could further their causes.

Ideological Groups

As the leader of the capitalist world and military ally of many nations, the United States found itself the target of numerous ideologically motivated terrorist groups. Left-wing organizations, such as the German Red Army Faction (also known as the Baader-Meinhof group), Japanese Red Army (JRA), Greek left-wing terrorists, and Philippine Communist terrorists, attacked Americans abroad. Many of these groups received support from Communist nations and Palestinian groups. Neo-fascist terrorists, some believed to have Middle Eastern backing and connections to right-wing extremists in the United States, also posed a potential threat to Americans in Europe, with their bombs at public gatherings killing almost 100 people in 1980 alone.

Nationalist and Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

Many terrorists have opposed the United States because of its actual or perceived role in their separatist or nationalist conflicts. U.S. citizens, while not directly targeted in most cases, were put at risk by the attacks of organizations such as the IRA, the Basque separatist organization ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, or Basque Homeland and Freedom), and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). However, the most significant of nationalist conflicts for the United States has been the struggle between the Palestinians and Israelis.

During the 1970s and ′80s, PLO and other Palestinian terrorists from secular and leftist factions killed numerous Americans during their operations abroad, which were sometimes coordinated with European and Japanese leftist terrorists. The Palestinian terrorist strategy and some of its major strikes are detailed in the previous chapter. However, the extensive list of Palestinian terrorism includes numerous other attacks on Americans. During a 1973 raid on a U.S. Pan American jetliner in Rome, terrorists slaughtered many passengers with machine-gun fire and grenades; a statement claimed the attack was retaliation for U.S. arms shipments to Israel. In October 1985 Palestinian commandos seized the Italian cruise liner Achille Lauro, killed wheelchair-bound American Leon Klinghoffer, and threw him into the sea. On March 30, 1986, a bomb made of Soviet-bloc Semtex plastic explosive blew up aboard TWA Flight 840 heading from Rome to Athens. The blast tore open a hole in the fuselage; four victims, including eight-month-old Demetra Klug, were sucked out and plummeted thousands of feet to their deaths. A Palestinian terrorist group called the attack revenge for a recent naval battle between the United States and Libya, an ally of Palestinian extremists and a state sponsor of terrorism.

State Sponsorship

Much of the world’s terrorism during the 1980s was backed by state sponsors—nations that supported terrorist groups as part of their international security policies. Aside from the Soviet bloc, which before its demise provided varying levels of patronage to a number of terrorist organizations, the United States traditionally counted Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Syria, Libya, Sudan, and Iraq as state sponsors.

Iran is the most important state sponsor of terrorism (discussed with other sponsors and terrorist groups in greater detail in the Appendix), in large part through its Quds Force (QF), a special unit of the country’s Revolutionary Guard. This has included support for anti-Israeli groups such as Hamas, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC), and Hizballah, long-time enemy of both Jerusalem and Washington. In recent years, the U.S. has presented substantial evidence of QF lethal action against U.S. troops in both Iraq and Afghanistan, most notably involving specially designed explosives able to penetrate American armored vehicles. Iran has also been linked to support of al-Qaida, from providing training in the group’s earlier days to sheltering al-Qaida fugitives in Iran after 9/11. In effect, the QF, often supported by its Hizballah bloodbrothers, has been engaged in a shadow war with the U.S. for decades. Given severe tensions between Washington and Tehran over the Iranian nuclear program, this raises grave concerns about the presence of Hizballah support cells in the U.S. which, with Hizballah and QF elements around the world must be considered a threat to the homeland and U.S. interests abroad should a broader conflict erupt.

Iran has also provided support and worked in coordination with state sponsor Syria which has continued to support Hizballah and Palestinian terrorist groups and assisted anti-American insurgents in Iraq. Publicly released data indicates the country was constructing a North Korean–designed nuclear plant until it was destroyed in 2007 by an Israeli air strike. The regime also gained attention for the brutal repression of its own citizens.

Other state sponsors reduced their support for terrorism in recent years. Libya was once considered perhaps the most flagrant state sponsor; its flamboyant dictator, Muammar Qadhafi, tangled with the United States for years, often using Palestinian and other terrorist groups to pursue his objectives. This included offering $2.5 million to a Chicago street gang called the El Rukns in return for terrorist attacks in the U.S. homeland—a scheme broken up by American law enforcement. After a Libyan-sponsored bombing killed two U.S. servicemen in Germany, U.S. war planes struck Libya in 1986. But Qadhafi continued his attacks, often using JRA terrorists. They targeted U.S. facilities abroad and, in April 1988, JRA terrorist Yu Kikumura was caught in a plot to set off bombs in New York City (he was reportedly released from prison and returned to Japan in 2007). The Libyan campaign peaked on December 21, 1988, when Pan Am Flight 103 exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 270 passengers and people on the ground.

In the face of U.S. and international pressure, Qadhafi ultimately renounced terrorism, agreed to compensate the families of Pan Am Flight 103 victims, and arranged to dismantle his WMD program. Ultimately the U.S. and its allies supported efforts by Libya’s citizens to overthrow him. Sudan also expanded its cooperation with the West, and Iraq’s terrorist sponsors—who had provided support to certain terrorist groups—were removed by the U.S. invasion. Cuba remained a sponsor, although far less active than in the past, in large part maintaining the ire of the U.S. for harboring ideological terrorists who fled America years before (Cuba noted accurately that it too had suffered terrorist attacks, in some cases from exiles once supported by the U.S. government).

In 2010 the United States recertified Venezuela as “not cooperating fully” with U.S. counterterrorism efforts after Venezuelan weapons turned up in the hands of Colombian terrorist groups such as the FARC and National Liberation Army (ELN). Some observers saw an even greater threat in the growing military relationship between Venezuela and Iran. Unconfirmed reports raised the possibility that the QF might be training members of FARC or other Latin Americas, providing Iran with potential means to strike America from the south.

Meantime, North Korea, enfeebled and often starving due to its Marxist economy, shifted focus from terrorism to organized crime and proliferation, allegedly providing nuclear and missile technology to Iran, Syria, and other nations.

Transnational Crime and Narco-terrorism

Besides global terrorist networks, other nonstate actors, with goals geared toward personal gain rather than public objectives, have significant consequences for homeland security. International criminal organizations participate in drug and arms trafficking, money laundering, cigarette smuggling, piracy, counterfeiting, illegal technology transfers, identity theft, public corruption, and illegal immigration. Assessments of the international crime threat are that it is pervasive, substantial, and growing.

There is no single global crime cartel, but evidence that groups have cooperated in joint operations. Though virtually no country is free of organized crime, notably large crime organizations are centered in China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), Colombia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, the United States, and Canada. Each group has extensive international links and cuts across regions of strategic concern to the United States. In recent years Albanian, Burmese, Filipino, Israeli, Jamaican, Korean, Thai, Nigerian, and Pakistani groups have also drawn the attention of international law enforcement. The organizations appear to be evolving, employing looser, more adaptive, and innovational command structures.

Such groups have been linked to terrorist organizations. “Terrorists and insurgents increasingly will turn to crime to generate funding and acquire logistical support from criminals, in part because of U.S. and Western success in attacking other sources of their funding. Terrorists and insurgents prefer to conduct criminal activities themselves; when they cannot do so, they turn to outside individuals and criminal service providers,” stated Director of National Intelligence James Clapper in 2011.

Narco-terrorism

In the area of drug smuggling, the nexus between terrorism and criminal activity is particularly troubling. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), a narco-terrorist organization is a “group that is complicit in the activities of drug trafficking to further or fund premeditated, politically motivated violence to influence a government or group of people.” The DEA reported the number of designated foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) involved in the global drug trade jumped from 14 groups in 2003 to 18 in 2008. Because “drugs and terror frequently share a common ground of geography, money, and violence,” keeping drug money from financing terror is an important part of the nation’s counterterrorism strategy.2

The international drug market can provide several benefits to terrorist groups. They can acquire operating funds from producing drugs or protecting those who do. For example, the perpetrators of the 2004 Madrid train bombings were reported to have financed the operation with proceeds of the Moroccan hashish trade. Al-Qaida affiliates in West Africa reportedly cooperated with Latin American traffickers to smuggle cocaine to Europe.

They also benefit from instability produced by drug trafficking and may see value in encouraging drug use in the United States and other enemy populations. The Taliban government of Afghanistan earned huge amounts of money from the opium trade during the time it was sheltering al-Qaida, and the DEA has claimed there is “multisource information” that Usama bin Ladin was involved in the financing and facilitation of heroin trafficking.3 The Afghan heroin trade continued after the U.S. invasion, providing operating funds for the Taliban.

The link between drugs and terror is most evident among the terrorist groups active in Colombia, such as the FARC. These groups are responsible for a substantial amount of cocaine and heroin sold in America. They have also targeted U.S. citizens and property in Colombia, often using their trademark strategy of kidnapping for ransom. According to public records, more than 70 Americans have been kidnapped by terrorist and criminal groups in Colombia; at least 13 have died. U.S. security assistance to the Colombian government also put Americans in harm’s way. The FARC reportedly described such assistance as an “act of war.” A U.S. pilot was killed by FARC guerrillas in 2003 after his plane crashed into the jungle. Three U.S. citizens flying with him were captured and held hostage by the group. Ultimately, however, U.S. assistance was credited with helping dramatically reduce FARC attacks.

CURRENT THREAT

The collapse of communism and establishment of negotiations to settle stubborn nationalist disputes, such as those in Ireland and Israel, have reduced or eliminated the power of some international terrorist groups.

Yet while PLO-affiliated groups reduced their international attacks, the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades continued to launch suicide strikes within Israel, killing U.S. citizens and many Israeli noncombatants. An even greater threat was posed by the Palestinian terrorist groups Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ). Dedicated to the destruction of Israel and hostile toward the United States, these radical Islamist groups mounted suicide bomb attacks against Israel, claiming numerous American lives. These activities peaked with major combat between Hamas and Israel in the Gaza Strip and Hizballah and Israel in Lebanon during the years after 9/11.

The FBI has repeatedly confirmed the capability of Hizballah, Hamas, and the PIJ to launch terrorist attacks inside the United States. Historically, however, these groups have reserved America for fund-raising, recruitment, and procurement. Investigations of their supporters revealed extensive criminal fund-raising and support efforts in the United States (including the use of cross-border operations with Mexico), where the groups can count on the assistance of numerous sympathizers. However, U.S. security officials believe these groups, especially Hizballah, might strike the homeland under certain circumstances, such as a major conflict between Iran and the United States.

This underscores the need for the United States to remain vigilant about groups with capability to attack the American homeland or U.S. citizens abroad, even if they are not thought to have such intent. A change in U.S. policy or an internal strategic decision could provide these groups with motive to attack suddenly and without warning.

Monitoring intents and capabilities is made more challenging by the evolving terrorist threat. As in the 1970s and ′80s, when terrorist groups with disparate ideologies cooperated in training and operations, modern international groups appear to share resources. For example, the Colombian government has asserted that at least seven IRA members provided training to members of the FARC in areas such as advanced explosives and mortar techniques (three men with IRA links were arrested in Colombiain 2001; although they were later acquitted, improvements in FARC tactics and other factors suggest IRA assistance). Information flow on effective techniques may occur even without direct contact between groups. There are claims that al-Qaida members received instruction in maritime terrorist techniques perfected by the Tamil separatists of the LTTE and explosives training from Iranian agents. Apparently passive groups, such as remnants of the Aum Shinrikyo group, remained capable of attacking U.S. citizens and presumably retained their traditional hostility to America.

Certain areas of the world have been called “petri dishes” of terrorism, including the remote intersection of Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil. “U.S. concerns have increased over activities of Hezbollah and the Sunni Muslim Palestinian group Hamas (Islamic Resistance Movement) in the tri-border area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, which has a large Muslim population. The TBA has long been used for arms and drug trafficking, contraband smuggling, document and currency fraud, money laundering, and the manufacture and movement of pirated goods,” the Congressional Research Service reported in 2011.4

AL-QAIDA AND OTHER ISLAMIST EXTREMIST GROUPS

Al-Qaida and affiliated groups, other radical Islamist organizations, and sponsors such as the nation of Iran represent the most potent terrorist threats against the United States. Their record of successful attacks across the globe demonstrates the power of the ideology that sustains them—Islamist extremism, a heretical perversion of religious doctrines. More than one billion people follow the Islamic faith. Most of them are not Arabs, but hail from such nations as Indonesia, Pakistan, and India. Other countries with large Muslim populations include Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Algeria, and Morocco. Significant numbers of Muslims live in many other nations, from the United States to China.

Only a small fraction of this population appears to support terrorism, but it is a fraction of a huge total, more than a fifth of the plane’s population, and represents a substantial pool of support and recruits for terrorist groups.

While the terrorists have twisted many of Islam’s principles, their ideology and motives draw upon its foundations. In order to understand the terrorists, it is critical to grasp their faith and view of history. In their eyes, these extremists are engaged in a historic battle that began many centuries ago and includes inspirational events that most Americans recognize vaguely if at all.

While many terrorist groups fight under the flag of religious battle, and there is cooperation among them, the threat is not monolithic. The groups are separated by factors such as religious sect, nationality, and ideology. Al-Qaida has sought to bring many of these groups together, while the nation of Iran has continued to support terrorism in the name of its own version of the faith. To the extent these efforts succeed, the threat to the American homeland will grow.

THE MUSLIM WORLD

It is wrong to equate the religion of Islam with terrorism. A distinction must be made between the religion Islam and a radical political agenda known as Islamism. Islamic extremists who advocate acts of terrorism may be properly termed Islamist terrorists, who seek to cloth their acts in the trappings of the Islamic religion.

The Basic Faith

Islam is a monotheistic religion whose basic belief is “There is no god but God (Allah), and Muhammad is his Prophet.” Islam in Arabic means “submission”; someone who submits to God is a Muslim. Muslims believe Muhammad, a merchant who lived in what is now Saudi Arabia from circa AD 570 to 632, received God’s revelations through the angel Gabriel. Words believed to have come directly from God through Muhammad were compiled into the Qur’an, Islam’s holy scripture.

According to Islam, Muhammad is the final prophet of God. The faith asserts that Abraham, Moses, and Jesus bore revelations from God, but it does not accept the deification of Christ. As in Judaism and Christianity, the religion includes concepts such as the eternal life of the soul, heaven and hell, and the Day of Judgment.

Five pillars of Islamic faith outline the key duties of every Muslim:

1. Shahada: Affirming the faith.

2. Salat: Praying every day, if possible five times, while facing Mecca.

3. Zakat: Giving alms. “It is broader and more pervasive than Western ideas of charity—functioning also as a form of income tax, educational assistance, foreign aid, and a source of political influence,” reported the 9/11 Commission, which explored the role of this tradition in generating funds for Islamist terrorism.5 Terrorists claim zakat requires the devoted to provide for their support.

4. Sawm: Fasting all day during the month of Ramadan.

5. Hajj: Making a pilgrimage to Mecca.

Islamic law, called the sharia, and other traditions outline social, ethical, and dietary obligations; for example, Muslims are not supposed to consume pork or alcohol. Religious leaders may also order fatwas, or religious edicts, authorizing or requiring certain actions. Finally, the Muslim faith includes the concept of jihad. Seen broadly, jihad means “striving” for the victory of God’s word, in one’s own life or that of the community. Seen narrowly, it refers to holy war against infidels, or nonbelievers, and apostates. Detailed Islamist legal guidance and historical precedent—including rules for combat in general and conflict against non-Muslims specifically—often guide those pursuing jihad as holy war. The concepts of jihad and fatwa have been commandeered by extremists, who, despite the disagreement of many Islamic leaders, use them to order and justify terrorism.

Perhaps most importantly, the Islamic tradition is all-encompassing, combining religious and secular life and law. This dramatically complicates attempts to understand Islamist ideology and countermeasures to it solely through the lens of traditional American political science. Separation between church and state, a central tenet of many Western societies, is seen as largely unnecessary by some Muslims and sacrilegious by Islamists.

After Muhammad’s death in 632, Muslims selected caliphs, or successors. These caliphates represented Islamic empires that combined religious and political power and lasted in various forms until 1924. As will be seen, the battles of these caliphates with the West bear an important role in the ideology of al-Qaida and other extremist groups. However, it was early disputes among Muslims over the identities of the rightful caliphs that led to schisms in Islam.

Sects and Schisms

After the death of Muhammad, struggles for succession led to a civil war that divided Muslims into sects, two of which remain most influential today.

Sunni

The largest denomination of Muslims is the Sunni branch. They make up the majority of most Middle Eastern countries and Indonesia, plus substantial populations in many other nations. Usama bin Ladin and most members of al-Qaida are Sunni. Sunnis believe themselves to be the followers of the sunna (practice) of the Prophet Muhammad.

Shiite

The second largest Islamic denomination, estimated to constitute some 10 to 15 percent of Muslims, is the Shiite (or Shi’a) sect. Shiite Muslims believe that Ali, the son-in-law of Muhammad, was the first of the 12 imams appointed by God to succeed the Prophet as the leader of Muslims. Iran is almost entirely Shiite and Iraq mostly so, although members of the Sunni minority in effect ruled Iraq under Saddam Hussein’s regime. Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have significant Shiite minorities.

Fundamentalism and Radicalism: Wahhabism, Salafiyya, and Beyond

Founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the 1700s, Wahhabism has become a powerful strain of the Muslim faith, a “back to basics” purification of Sunni Islam. Its theological power was matched by the economic clout of its best-known adherents, the al-Saud dynasty, which conquered the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, creating Saudi Arabia in 1924. Since then, the Saudi government has used petrodollars to spread this variant of Islam, whose most extreme dimensions captured the imagination of Saudi native Usama bin Ladin.

Other important Islamic doctrines are the Takfir and Salafist systems. Salafists demand a return to the type of Islam practiced in its first generation, before what they regard as its corruption. They seek the absolute application of sharia, or religious law. Takfiris are committed to attacking false rulers and apostates. According to Takfir doctrine, members may violate Islamic laws, such as by drinking alcohol or avoiding mosques, in order to blend in with the enemy.

People who view Islam as a model for both religious and political governance, especially those who reject current government models in Islamic nations, are often called Islamists. Jihadists is a word often used for those committed to waging holy war against the West and what they consider apostate rulers in Muslim-populated nations. However, some critics contend that even using these words provides undeserved religious legitimacy to the terrorist cause and defames Islamic.

Modern Challenges

As discussed earlier, political oppression is linked to terrorism. While poverty is not a proven cause of terrorism, it creates conditions that can allow terrorist groups to operate and recruit. Both circumstances are common in the Islamic world. Countries with a majority of Muslims are far less likely to be free than other nations. They also tend to be poorer. Many Muslim regions are also experiencing a “youth bulge,” with a disproportionate number of citizens in the 15-to–29-year-old age range, for whom poor economic and educational prospects may increase the attraction of extremism and the pool of potential terrorists. Finally, large numbers of refugees are found in many Muslim nations, creating social strains and providing sanctuary for extremists.6

IDEOLOGY OF ISLAMIST TERRORISM

Where leftist and many separatist terrorist groups have focused on producing new social structures, in certain ways Islamist extremists fight to re-create the past. In a manner foreign to many Westerners, these terrorists harken back to a sacred and glorious past of the “Caliphate.” They also appeal to what bin Ladin and others refer to as the “Islamic Nation,” an idealized vision of a massive and united international Islamic population transcending national, ethnic, and class boundaries.

Glorious Past and Bitter Defeats

Islamist extremists often attempt to cast their actions as a defensive jihad against U.S. and Israeli aggression, placing current conflicts in the context of a war for religious control of the world that began more than 1,000 years ago. Following the birth of Islam, Muslim influence spread rapidly, as did the development of nations that practiced the faith. The religion expanded across the globe, including large parts of Europe such as Spain. During medieval times, the caliphates were militarily powerful, economically vibrant, and scientifically advanced.

House of Islam; House of War

As scholar Bernard Lewis described, growth of the Islamic world was central to the Muslim philosophy: “In principle, the world was divided into two houses: the House of Islam, in which a Muslim government ruled and Muslim law prevailed, and the House of War, the rest of the world, still inhabited and, more important, ruled by infidels. Between the two, there was to be a perpetual state of war until the entire world either embraced Islam or submitted to the rule of the Muslim state.”7

The Crusades

During this time, Islam also came into conflict with Christianity. In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church organized crusades, military campaigns initially focused on capturing the holy city of Jerusalem from Muslim control. In the West, crusade ultimately became a word that described the fight for a noble cause. But in the Islamic world, the word was understood to mean an invasion by infidels and still resonates today. Bin Ladin repeatedly invoked the name of famous Muslim warriors from the crusades, including Saladin, who defeated the Christians and recaptured Jerusalem during the twelfth century.

Muslim Strength Fades

But the military might of the Muslim nations flagged. By the early 1900s, European powers had conquered most of the Muslim world and carved up much of it into colonies. As the colonialists withdrew in succeeding decades, they left behind a Muslim world divided into different countries, often ruled by secular strong men.

“After the fall of our orthodox caliphates on March 3, 1924 and after expelling the colonists, our Islamic nation was afflicted with apostate rulers.… These rulers turned out to be more infidel and criminal than the colonialists themselves. Moslems have endured all kinds of harm, oppression, and torture at their hands,” concludes the so-called “Al-Qaeda Manual,” a detailed operational guide found in the home of a British suspect in al-Qaida’s 1998 embassy bombings and entered into evidence by the U.S. Department of Justice (tactical insights from the Manual are discussed in Chapter 13).8

Extremism Rises

The violent Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928, fought against colonial governments and secular “apostate” Muslim rulers for a return to Islamist governance. Represented in scores of countries, the Brotherhood became especially active in Egypt after World War II and engaged in bloody battles across the Middle East, fighting the influence of secular pan-Arabist and Communist ideologies.

The Evolution of Religious-Inspired Terrorism

In 1979 Islamist extremists entered battle with the world’s two superpowers. These events combined to light the fuse on what would become an explosion of Muslim extremism and conflict that would lead to 9/11. That year the U.S.-installed shah of Iran was toppled by the Ayatollah Khomeini, a charismatic Shiite religious leader supported by trained operatives from PLO camps and far more Iranian citizens who hated the shah’s despotic regime. Iran’s new leader promptly declared America the “Great Satan” and allowed his followers to seize the U.S. embassy in Tehran and hold 52 hostages. Khomeini’s triumph fueled religious fundamentalism across the Middle East, along with disdain for the United States, whose response to the hostage taking was a botched raid that left dead American troops and burned equipment strewn across the Iranian desert.

Even followers of rival Muslim sects such as the Sunnis appeared energized by Khomeini’s triumphs. Days after the occupation of Iran’s U.S. embassy, Islamist radicals in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, seized the Grand Mosque and hundreds of hostages. Rooted out by a bloody military operation, many of the terrorists were publicly beheaded by Saudi authorities. In Libya, a mob—unchecked by local authorities—burned the U.S. embassy.

Extremists were further infuriated when the Israel–Egypt peace treaty was signed that same year (Egyptian president Anwar Sadat was assassinated two years later). Finally, in December the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, starting a war against Islamist guerrillas that would contribute to the collapse of communism and the emergence of twenty-first-century terrorism.

1980s: Emergence of Shiite Extremist Terrorism

In 1981 Tehran released its American hostages, due in part to Iranian fears of attack from incoming president Ronald Reagan. Embroiled in a debilitating war with neighboring Iraq, the fundamentalist regime increasingly turned to terrorism as a tool. Iranian hit teams targeted opponents around the world. For example, a former Iranian diplomat was murdered in Maryland by an American operative dressed as a postal worker; the accused killer later surfaced in Iran. At the same time, Tehran began sponsoring a variety of terrorist groups. One of them, al-Dawa, or “The Call,” was dedicated to attacking Iraqi interests. In December 1981, the group demonstrated a terrorist technique previously unfamiliar to many, dispatching a suicide bomber to demolish Iraq’s embassy in Beirut. Lebanon had become a cauldron of religious and political hatred containing Syrian and Israeli invaders, local religious militias, and Iranian Revolutionary Guards. Into that caustic mix landed the U.S. Marines, dispatched to separate the nation’s warring factions in late 1982. In Beirut the Americans would meet Imad Mughniyah, their most lethal foe until the days of bin Ladin, and his Hizballah organization, backed by Iran with support from Syria.

Hizballah, whose members hated the Israelis and aimed to make Lebanon a Shiite Muslim state, wanted the Americans out of the way. On April 18, 1983, a suicide bomber blew up the U.S. embassy in Beirut, killing 63 people, including 17 Americans, among them many of the CIA’s leading experts on the region. The blast was linked to Islamic Jihad, a front name for Hizballah and other Iranian-supported terrorist groups.

The Marines, hunkered down in strategically execrable emplacements near the Beirut airport, tangled with a complicated assortment of adversaries struggling for the future of Lebanon. Shortly before reveille on the warm morning of October 23, a yellow Mercedes truck roared over concertina wire obstacles, passed two guard posts before sentries could get off a shot, slammed through a sandbagged position at the entrance to the barracks, and exploded with the force of 12,000 pounds of dynamite. The building, yanked from its foundations by the blast from the advanced device, imploded, crushing its inhabitants under tons of broken concrete and jagged steel. Simultaneously, a second suicide bomber hit the Beirut compound housing French paratroopers. When rescuers finished tearing through the smoking rubble, while dodging fire from enemy snipers, they counted 241 Americans and 58 French troops dead. Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility.

The American public clamored for a response. President Reagan considered major attacks on the Syrian-controlled Bekaa Valley, where Iranian Revolutionary Guards supported Hizballah. But after disagreements in the administration, Reagan settled for shelling and a limited air strike on other targets (including Syrian positions)—attacks that were seen as ineffective by American adversaries and allies alike. For months the Marines kept up the fight, sustaining numerous casualties. But as the Lebanese security situation continued to disintegrate, the administration pulled the leathernecks from Lebanon in February 1984.

Hizballah continued its attacks, among them hijacking a plane and killing passenger Robert Stethem, a passenger from the U.S. Navy; kidnapping numerous Western hostages; and murdering a captive American CIA official and a Marine officer, allegedly with the close cooperation of Tehran (a terrorist convicted by Germany in connection with the killing of Robert Stethem was released in 2005; according to unconfirmed media reports, he had been swapped for a German citizen captured in Iraq). By the early 1990s, the organization had emerged as a political movement in Lebanon and expanded from its Middle Eastern base to strongholds in Latin America’s tri-border area where Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay meet. Mughniyah, the purported killer of Americans in Lebanon, and his Iranian sponsors were linked to two huge car bomb attacks on Jewish targets in Argentina that left more than 100 dead.

1990s: Emergence of Sunni Extremist Terrorism

Unable to afford Afghanistan’s price in blood and gold, the Soviets began to withdraw in 1988. The ebbing tides of war left aground thousands of hardened foreigner mujahideen (holy warriors) who had traveled across the world to fight communism in support of radical Islam. A 6-foot, 6-inch, left-handed Saudi multimillionaire and mujahideen financier decided to help the so-called Afghan Arabs identify their next battle. In 1988 Usama bin Ladin began forming an organization of these militants; he called it al-Qaida (“the base” in English) after a training camp in Afghanistan. (The CIA provided funding and weapons to the mujahideen but denies having supported bin Ladin directly during the Soviet war.)

As discussed earlier, bin Ladin went on to mold al-Qaida into an Islamist terrorist “organization of organizations” that combined numerous organizations with members from dozens of nations.

The Enemies: The United States and Its Allies

The international fighters turned their attention to the governments of such Islamic countries as Egypt and Saudi Arabia, the so-called “near enemies” which they viewed as apostates, and the United States, Israel, and the United Nations, the “far enemies” which they considered infidels and blood enemies. Al-Qaida began developing an ideology based on the eviction of the United States from the Middle East, the overthrow of U.S. allies in the Islamic world, and the destruction of the Israeli state. This call of Islamist extremism proved magnetic for many Muslims angry with PLO compromises, aware of communism’s failure as a model, and unmoved by self-proclaimed pan-Arabist secular leaders such as Libya’s Muammar Qadhafi and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. The collapse of Soviet communism, for which the mujahideen claimed partial credit, emboldened radicals with a belief they could defeat the remaining superpower.

The U.S.-led war against Hussein in early 1991 fueled the movement; when the United States permanently positioned troops in Saudi Arabia after the war, al-Qaida saw it as a galvanizing issue and promised to drive the “crusaders” from the “land of the two holy mosques” (Mecca and Medina). Over coming years, al-Qaida and its supporters would establish a record of delivering on their promises, even returning to targets, such as the World Trade Center and U.S. Navy ships in Yemen, to complete their destruction.

Major operations executed, coordinated, or inspired by al-Qaida include bombings targeted at U.S. troops in Yemen during 1992; assistance to guerrillas who killed numerous U.S. troops in Somalia in 1993; the car bomb killing of five Americans in Saudi Arabia during 1995; bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that killed some 300 people in 1998; the planned bombing of the Los Angeles airport in 1999; the murder of 17 U.S. sailors in a suicide attack on the USS Cole in 2000; the 9/11 attacks; and deadly strikes in Iraq, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Indonesia, and other locations.

COMMON FRONT AGAINST THE WEST

Long divided by denomination, ethnicity, and other factors, Islamist extremists have found common cause in their hatred of the United States. Al-Qaida sought to exploit this by rallying extremist organizations to its side. In February 1998 bin Ladin announced a new terrorist alliance, the “International Islamic Front for Jihad against the Jews and Crusaders.” The group issued a fatwa, or Islamic religious ruling: “The ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it … We—with Allah’s help—call on every Muslim who believes in Allah and wishes to be rewarded to comply with Allah’s order to kill the Americans and plunder their money wherever and whenever they find it. We also call on Muslim ulema [religious figures], leaders, youths, and soldiers to launch the raid on Satan’s U.S. troops and the devil’s supporters allying with them, and to displace those who are behind them so that they may learn a lesson.”9

Sunni and Shiite Extremists Cooperate

Although the Islamic Front was composed of Sunni Muslims, as discussed earlier there have been signs of cooperation between its members and the Shiite Hizballah and Iranians. An arrested al-Qaida operative testified to ties between that group and Hizballah. The 9/11 Commission reported that al-Qaida operatives had received training from Hizballah, that bin Ladin was interested in Hizballah’s tactics in the 1983 bombing of U.S. Marines in Lebanon, and that the groups had other contacts. While Sunni and Shiite extremists have different political agendas and contrasting religious views, and have engaged in bloody warfare in places such as Iraq, they sometimes cooperate when operations are in their mutual interest, including in combat against the U.S.

Success in a Common Goal

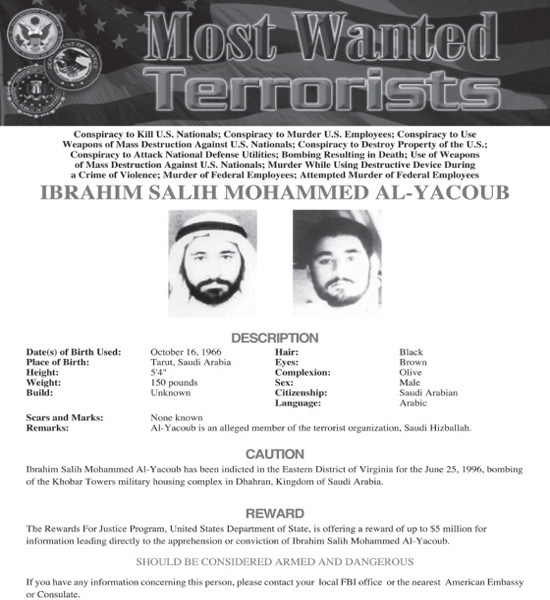

On June 25, 1996, a sophisticated truck bomb tore apart the Khobar Towers, a U.S. military complex in Dharan, Saudi Arabia, killing 19 Americans and wounding hundreds more. “We thought it was the end of the world. Some were crying; some just sat on the ground and held their ears,” said a witness. The attack followed another bombing of Americans a year earlier in Saudi Arabia; an attack the 9/11 Commission reported was supported financially by bin Ladin.

The Khobar Towers attack, which produced images of destruction similar to the 1983 Marine barracks bombing, produced an outcry in the United States. “I am outraged by it,” declared President Clinton. As President Reagan before him, Clinton promised, “The cowards who committed this murderous act must not go unpunished.”10 But they did. Later identified in a U.S. indictment as Saudi Shiite extremists backed by Iran and linked to Hizballah, the Khobar bombers remained free after their attack. According to the 9/11 Commission, there were signs al-Qaida also played a role in the attack.

America responded to the terrorist threat in Saudi Arabia by pulling out of the Khobar Towers and relocating its troops to a remote area of Saudi Arabia; by the summer of 2003, most U.S. troops would be out of Saudi Arabia entirely.

Potential for Ongoing Cooperation

The withdrawal from Saudi Arabia concluded after the U.S. liberation of Iraq; the quick and successful initial stage of that operation lessened the need for a Saudi base. But the operation appeared to energize Hizballah. With agents on four continents, they reportedly continued to conduct surveillance on U.S. facilities. Around the same time, Hizballah’s leader was reiterating the group’s position on the United States. “In the past, when the Marines were in Beirut, we screamed, ‘Death to America!’” Hassan Nasrallah declared in 2003. “Today, when the region is being filled with hundreds of thousands of American soldiers, ‘Death to America!’ was, is and will stay our slogan.”11 While Hizballah had not been known to launch attacks in the United States, U.S. officials stepped up their scrutiny of the group’s operatives in the homeland.

FIGURE 11.1

MOST WANTED TERRORISTS

Iraq and Afghanistan as Magnets

Following 9/11, extended U.S. warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan created a destination for Islamist extremists, much as Soviet-occupied Afghanistan and to a lesser extent Lebanon had in years before. U.S. forces captured hundreds of foreign fighters in Iraq, many with links to al-Qaida. The Ansar al-Islam group and the linked Jama’at al-Tawhid and Jihad organizations, also called the al-Zarqawi network, led by Sunni extremist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, carried out operations against U.S. and other coalition and UN targets (al-Zarqawi was killed by a U.S. airstrike in 2006). Indiscriminate slaughter of civilians by elements of these groups helped turn influential elements of Iraqi society against them. Hizballah and Iranian agents also infiltrated the country. According to the U.S. government, Iranian agents provided sophisticated weaponry for use against U.S. troops, as well as conducting direct operations against American and allied forces. Despite brutal attacks against one another, Shiite and Sunni extremists united in opposition to U.S. plans for a democratic government in Iraq.

In Afghanistan Iranian agents, foreign terrorists and extremists from neighboring Pakistan joined fighting against U.S. and allied forces, often from sanctuaries in the tribal areas of Pakistan. For example, the Tehrik-E Taliban Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban, operated in Afghanistan and Pakistan and also launched the failed 2010 Times Square bombing.

A controversial issue surrounding the wars, especially after the ejection of al-Qaida from Afghanistan, was whether on balance they improved homeland security by eradicating terrorist sanctuaries and midwifing relatively tolerant and democratic regimes in the Muslim world, or increased terrorist recruiting by playing into Islamist propaganda themes of a U.S. war against Islam.

Not in dispute was the success of U.S. and allied military attacks, along with suffocating intelligence and law enforcement blankets, on al-Qaida Core or Central, the group’s traditional leadership in Afghanistan and Pakistan. But with Bin Ladin dead and his organization deeply wounded by 2011, other Sunni terrorist groups, notably al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula and the Pakistani Taliban, rose to prominence. As detailed elsewhere in this book, these groups not only sought to attack the U.S. homeland but also managed to enlist or inspire the support of a small but dangerous collection of U.S. citizen terrorists both abroad and at home.

Democracy Is a Deviation

Following 9/11, U.S. leaders often declared the importance of increasing democracy in the Middle East and across the Muslim world. But the relative liberalism of new governments in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the optimism of the Arab Spring, did not signal the vanquishing of Islamist terrorism. The driving principle of Islamist extremism is that legitimate Islamic nations must submit only to Allah’s laws, not man’s, and that violence to achieve that result is not just acceptable, but required. Increasing human rights in Muslim lands may reduce the popularity of this sentiment but seem unlikely to eliminate it any time soon.

As Anwar al-Awlaki, the influential Islamist propagandist and terrorist leader, put it before he was killed in 2011 by U.S. forces: “We will implement the rule of Allah on Earth by the tip of the sword whether the masses like it or not.”12

PROFILES OF SIGNIFICANT INTERNATIONAL TERRORIST GROUPS AND STATE SPONSORS

For detailed information on significant terrorist groups, see the Appendix.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Over recent decades, the primary terrorist threat to the U.S. homeland from international terrorists has shifted from traditional groups motivated by ideological, nationalist, and state-sponsored goals to Islamist extremists. However, several nationalist and ideological groups, along with the remnants of the Aum Shinrikyo cult, maintain both a capability to strike U.S. citizens and a hostility toward U.S. policies. History also indicates the likelihood that additional international terrorist threats will emerge against the United States.

Islamist extremists will continue to present a particular challenge. These terrorists believe they are fighting a war that has lasted for centuries and will continue on a divine basis until they prevail. Comprised of numerous organizations and numbering many thousands of hardened operatives and active supporters, the Islamist extremist movement is not monolithic but sometimes capable of cooperation. It will harness the most effective weapons it can muster to achieve victory. Democracy and economic reform may lessen the appeal of these groups but will not eliminate their rallying cry or potential for catastrophic violence.

CHAPTER QUIZ

1. What is international terrorism?

2. List two major international terrorist groups, other than al-Qaida, that have conducted support operations in the United States during recent years.

3. Identify a major international terrorist group, other than al-Qaida, with the capability to attack U.S. citizens.

4. What is narco-terrorism?

5. Name a terrorist state sponsor that dramatically reduced its support for terrorism.

NOTES

1. Leslie Maitland, “Witnesses Tell of Horror,” New York Times (December 30, 1975), 75.

2. Statement of Karen P. Tandy, Administrator, Drug Enforcement Administration, before the House Committee on International Relations (February 12, 2004), www.dea.gov/pubs/cngrtest/ct021204.htm.

3. Statement of Asa Hutchinson, Administrator, Drug Enforcement Administration, before the Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Technology, Terrorism, and Government Information (March 13, 2002), www.dea.gov/pubs/cngrtest/ct031302.html.

4. Mark P. Sullivan, Latin America: Terrorism Issues, Congressional Research Service (February 23, 2011), http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/terror/RS21049.pdf

5. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (July 22, 2004), 372.

6. John L. Helgerson, “The National Security Implications of Global Demographic Change,” Remarks to the Denver World Affairs Council and the Better World Campaign, Denver, Colorado, April 30, 2002, www.cia.gov/nic/speeches_demochange.html; Freedom House, “Freedom in the World Survey,” www.freedomhouse.org/research/muslimpop2004.pdf; Michael Cosgrove, “International Economics and State-Sponsored Terrorism,” Journal of the Academy of Business and Economics (February 2003), articles.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0OGT/is_2_1/ai_113563605.

7. Bernard Lewis, “The Revolt of Islam,” New Yorker (November 19, 2001), www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?011119fa_FACT2.

8. “Military Studies in the Jihad against the Tyrants” (or “Al Qaeda Manual”), (date of writing unknown; reported to have been seized in 2000). 8. http://www.justice.gov/ag/manual-part1_1.pdf

9. World Islamic Front Statement, “Jihad against Jews and Crusaders” (February 23, 1998), www.fas.org/irp/world/para/docs/980223-fatwa.htm.

10. Philip Shenon, “23 U.S. Troops Die in Truck Bombing in Saudi Base,” New York Times (June 26, 1996), A1.

11. Josh Meyer, “Hezbollah Vows Anew to Target Americans. Bush Officials, Fearing Attacks, Debate Whether to Go after the Group and Backers of Iran and Syria,” Los Angles Times (April 17, 2003), 1, www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/iraq/world/la-war-hezbollah-17apr17,1,4681007.story?coll=la%2Dhome%2DheadlinesApril 17,2003.

12. Brooks Egerton, “Imam’s E-Mails To Fort Hood Suspect Hasan Tame Compared To Online Rhetoric,” Dallas Morning News (November 29, 2009), http://www.dallasnews.com/news/state/headlines/20091129-Imam-s-e-mails-to-Fort–7150.ece