Chapter 1. Making HR Measurement Strategic

This book will help you better understand how to analyze, measure, and account for investments in people. However, although data and analysis are important to investing in people, they are really just a means to an end. The ultimate purpose of an investment framework is to improve decisions about those investments. Decisions about talent, human capital, and organizational effectiveness are increasingly central to the strategic success of virtually all organizations.

According to 2010 research from the Hay Group, businesses listed in Fortune magazine as the world’s most admired companies invest in people and see them as assets to be developed, not simply as costs to be cut. Consider how the three most admired companies in 64 industries—firms like UPS, Disney, McDonald’s, and Marriott International—managed their people during the Great Recession, compared to their less-admired peers. Those companies were less likely to have laid off any employees (10 percent versus 23 percent, respectively). By even greater margins, they were less likely to have frozen hiring or pay, and by a giant margin (21 points), they were more likely to have invested the money and the effort to brand themselves as employers, not just as marketers to customers. They treat their people as assets, not expenses. Perhaps the most important lesson from the 2010 World’s Most Admired companies is that they did not launch their enlightened human capital philosophies when the recession hit; they’d been following them for years. Once a recession starts, it’s too late. “Champions know what their most valuable asset is, and they give it the investment it deserves—through good times and bad” (p. 82).1

It is surprising how often companies address vital decisions about talent and how it is organized with limited measures or faulty logic. How would your organization measure the return on investments that retain vital talent? Would the future returns be as clear as the tangible short-term costs to be saved by layoffs? Does your organization have a logical and numbers-based approach to understanding the payoff from improved employee health, improvements in how employees are recruited and selected, reductions in turnover and absenteeism, or improvements in how employees are trained and developed? In most organizations, leaders who encounter such questions approach them with far less rigor and analysis than questions about other resources such as money, customers, and technology. Yet measures have immense potential to improve the decisions of HR and non-HR leaders.

This book is based on a fundamental principle: HR measurement adds value by improving vital decisions about talent and how it is organized.

This perspective was articulated by John Boudreau and Peter Ramstad in their book, Beyond HR.2 It means that HR measurements must do more than evaluate the performance of HR programs and practices, or prove that HR can be made tangible. Rather, it requires that HR measures reinforce and teach the logical frameworks that support sound strategic decisions about talent.

In this book, we provide logical frameworks and measurement techniques to enhance decisions in several vital talent domains where decisions often lag behind scientific knowledge, and where mistakes frequently reduce strategic success. Those domains are listed here:

• Absenteeism (Chapter 3)

• Employee turnover (Chapter 4)

• Employee health and welfare (Chapter 5)

• Employee attitudes and engagement (Chapter 6)

• Work-life issues (Chapter 7)

• External employee sourcing (recruitment and selection) (Chapter 8)

• The economic value of employee performance (Chapter 9)

• The value of improved employee selection (Chapter 10)

• The costs and benefits of employee development (Chapter 11)

Each chapter provides a logical framework that describes the vital key variables that affect cost and value, as well as specific measurement techniques and examples, often noting elements that frequently go unexamined or are overlooked in most HR and talent-measurement systems.

The importance of these topics is evident when you consider how well your organization would address the following questions if your CEO were to pose them:

Chapter 2: “I see that there is a high correlation between employee engagement scores and sales revenue across our different regions. Does that mean that if we raise engagement scores, our sales go up?”

Chapter 3: “I know that, on any given day, about 5 percent of our employees are absent. Yet everyone seems to be able to cover for the absent employees, and the work seems to get done. Should we try to reduce this absence rate, and if we did, what would be the benefit to our organization?”

Chapter 4: “Our total employment costs are higher than those of our competitors, so I need you to lay off 10 percent of our employees. It seems “fair” to reduce headcount by 10 percent in every unit, but we project different growth in different units. What’s the right way to distribute the layoffs?”

Chapter 4: “Our turnover rate among engineers is 10 percent higher than that of our competitors. Why hasn’t HR instituted programs to get it down to the industry levels? What are the costs or benefits of employee turnover?”

Chapter 5: “In a globally competitive environment, we can’t afford to provide high levels of health care and health coverage for our employees. Every company is cutting health coverage, and so must we. There are cheaper health-care and insurance programs that can cut our costs by 15 percent. Why aren’t we offering cheaper health benefits?”

Chapter 6: “I read that companies with high employee satisfaction have high financial returns, so I want you to develop an employee engagement measure and hold our unit managers accountable for raising the average employee engagement in each of their units.”

Chapter 7: “I hear a lot about the increasing demand for work and life fit, but my generation found a way to work the long hours and have a family. Is this generation really that different? Are there really tangible relationships between work-life conflict and organizational productivity? If there are, how would we measure them and track the benefits of work-life programs?”

Chapter 8: “We expect to grow our sales 15 percent per year for the next 5 years. I need you to hire enough sales candidates to increase the size of our sales force by 15 percent a year, and do that without exceeding benchmark costs per hire in our industry. What are those costs?”

Chapter 9: “What is the value of good versus great performance? Is it necessary to have great performance in every job and on every job element? Where should I push employees to improve their performance, and where is it enough that they meet the minimum standard?”

Chapter 10: “Is it worth it to invest in a comprehensive assessment program, to improve the quality of our new hires? If we invest more than our competition, can we expect to get higher returns? Where is the payoff to improved selection likely to be the highest?”

Chapter 11: “I know that we can deliver training much more cheaply if we just outsource our internal training group and rely on off-the-shelf training products to build the skills that we need. We could shut down our corporate university and save millions.”

In every case, the question or request reflects assumptions about the relationship between decisions about human resource (HR) programs and the ultimate costs or benefits of those decisions. Too often, such decisions are made based on very naïve logical frameworks, such as the idea that a proportional increase in sales requires the same proportional increase in the number of employees, or that across-the-board layoffs are logical because they spread the pain8 equally. In this book, we help you understand that these assumptions are often well meaning but wrong, and we show how better HR measurement can correct them.

Two issues are at work here. First, business leaders inside and outside of the HR profession need more rigorous, logical, and principles-based frameworks for understanding the connections between human capital and organization success. Those frameworks comprise a “decision science” for talent and organization, just as finance and marketing comprise decision sciences for money and customer resources. The second issue is that leaders inside and outside the HR profession are often unaware of existing scientifically supported ways to measure and evaluate the implications of decisions about human resources. An essential pillar of any decision science is a measurement system that improves decisions, through sound scientific principles and logical relationships.

The topics covered in this book represent areas where very important decisions are constantly made about talent and that ultimately drive significant shifts in strategic value. Also, they are areas where fundamental measurement principles have been developed, often through decades of scientific study, but where such principles are rarely used by decision makers. This is not meant to imply that HR and business leaders are not smart and effective executives. However, there are areas where the practice of decisions lags behind state-of-the-art knowledge.

The measurement and decision frameworks in these chapters are also grounded in general principles that support measurement systems in all areas of organizational decision making; such principles include data analysis and research design, the distinction between correlations and causes, the power of break-even analysis, and ways to account for economic effects that occur over time. Those principles are described in Chapter 2, “Analytical Foundations of HR Measurement,” and then used throughout this book.

Next, we show how a decision-science approach to HR measurement leads to very different approaches from the traditional one, and we introduce the frameworks from this decision-based approach that will become the foundation of the rest of this book.

How a Decision Science Influences HR Measurement

When HR measures are carefully aligned with powerful, logical frameworks, human capital measurement systems not only track the effectiveness of HR policies and practices, but they actually teach the logical connections, because organization leaders use the measurement systems to make decisions. This is what occurs in other business disciplines. For example, the power of a consistent, rigorous logic, combined with measures, makes financial tools such as economic value added (EVA) and net present value (NPV) so useful. They elegantly combine both numbers and logic, and help business leaders improve in making decisions about financial resources.

Business leaders and employees routinely are expected to understand the logic that explains how decisions about money and customers connect to organization success. Even those outside the finance profession understand principles of cash flow and return on investment. Even those outside the marketing profession understand principles of market segmentation and product life cycle. In the same way, human capital measurement systems can enhance how well users understand the logic that connects organization success to decisions about their own talent, as well as the talent of those whom they lead or work with. To improve organizational effectiveness, HR processes, such as succession planning, performance management, staffing, and leadership development, must rely much more on improving the competency and engagement of non-HR leaders than on anything that HR typically controls directly.

Why use the term science? Because the most successful professions rely on decision systems that follow scientific principles and have a strong capacity to quickly incorporate new scientific knowledge into practical applications. Disciplines such as finance, marketing, and operations provide leaders with frameworks that show how those resources affect strategic success, and the frameworks themselves reflect findings from universities, research centers, and scholarly journals. Their decision models and their measurement systems are compatible with the scholarly science that supports them. Yet with talent and human resources, the frameworks that leaders in organizations use often bear distressingly little similarity to the scholarly research in human resources and human behavior at work3 The idea of evidence-based HR management requires creating measurement systems that encourage and teach managers how to think more critically and logically about their decisions, and to make decisions that are informed and consistent with leading research.4

A vast array of research focuses on human behavior at work, labor markets, how organizations can better compete with and for talent, and how that talent is organized. Disciplines such as psychology, economics, sociology, organization theory, game theory, and even operations management and human physiology all contain potent research frameworks and findings based on the scientific method. A scientific approach reveals how decisions and decision-based measures can bring the insights of these fields to bear on the practical issues confronting organization leaders and employees. You will learn how to use these research findings as you master the HR measurement techniques described in this book.

Decision Frameworks

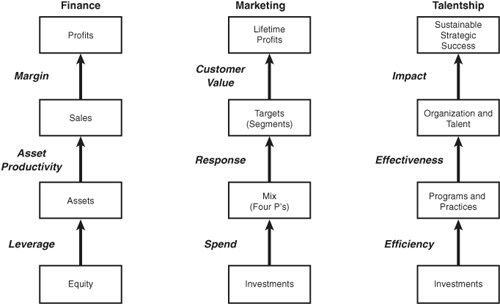

A decision framework provides the logical connections between decisions about a resource (for example, financial capital, customers, or talent) and the strategic success of the organization. This is true in HR, as we show in subsequent chapters that describe such connections in various domains of HR. It is also true in other, more familiar decision sciences such as finance and marketing. It is instructive to compare HR to these other disciplines. Figure 1-1 shows how a decision framework for talent and HR, which Boudreau and Ramstad called “talentship,” has a parallel structure to decision frameworks for finance and marketing.

Figure 1-1. Finance, marketing, and talentship decision frameworks.

Finance is a decision science for the resource of money, marketing is the decision science for the resource of customers, and talentship is the decision science for the resource of talent. In all three decision sciences, the elements combine to show how one factor interacts with others to produce value. Efficiency refers to the relationship between what is spent and the programs and practices that are produced. Effectiveness refers to the relationship between the programs or practices and their effects on their target audience. Impact refers to the relationship between the effects of the practice on the target audience and the ultimate success of the organization.

To illustrate the logic of such a framework, consider marketing as an example. Investments in marketing produce a product, promotion, price, and placement mix. This is efficiency. Those programs and practices produce responses in certain customer segments. This is effectiveness. Finally, the responses of customer segments create changes in the lifetime profits from those customers. This is impact.

Similarly, with regard to talent decisions, efficiency describes the connection between investments in people and the talent-related programs and practices they produce (such as cost per training hour). Effectiveness describes the connection between the programs/practices and the changes in the talent quality or organizational characteristics (such as whether trainees increase their skill). Impact describes the connection between the changes in talent/organization elements and the strategic success of the organization (such as whether increased skill actually enhances the organizational processes or initiatives that are most vital to strategic success).

The chapters in this book show how to measure not just HR efficiency, but also elements of effectiveness and impact. In addition, each chapter provides a logical framework for the measures, to enhance decision making and organizational change. Throughout the book, we attend to measures of efficiency, effectiveness, and impact. The current state of the art in HR management is heavily dominated by efficiency measures, so this book will help you see beyond the most obvious efficiency measures and put them in the context of effectiveness and impact.

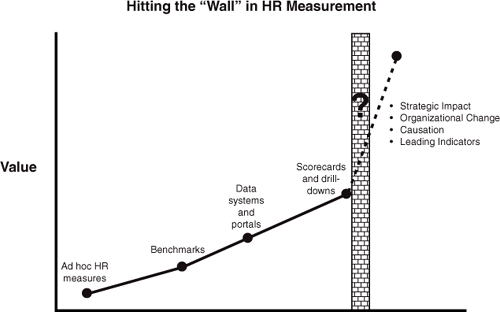

In a well-developed decision science, the measures and data are deployed through management systems, used by leaders who understand the principles, and supported by professionals who add insight and expertise. In stark contrast, HR data, information, and measurement face a paradox today. There is increasing sophistication in technology, data availability, and the capacity to report and disseminate HR information, but investments in HR data systems, scorecards, and integrated enterprise resource systems fail to create the strategic insights needed to drive organizational effectiveness. HR measures exist mostly in areas where the accounting systems require information to control labor costs or to monitor functional activity. Efficiency gets a lot of attention, but effectiveness and impact are often unmeasured. In short, many organizations are “hitting a wall” in HR measurement.

Hitting the “Wall” in HR Measurement5

Type “HR measurement” into a search engine, and you will get more than 900,000 results. Scorecards, summits, dashboards, data mines, data warehouses, and audits abound. The array of HR measurement technologies is daunting. The paradox is that even when HR measurement systems are well implemented, organizations typically hit a “wall.” Despite ever more comprehensive databases and ever more sophisticated HR data analysis and reporting, HR measures only rarely drive true strategic change.6

Figure 1-2 shows how, over time, the HR profession has become more elegant and sophisticated, yet the trend line doesn’t seem to be leading to the desired result. Victory is typically declared when business leaders are induced or held accountable for HR measures. HR organizations often point proudly to the fact that bonuses for top leaders depend in part on the results of an HR “scorecard.” For example, incentive systems might make bonuses for business-unit managers contingent on reducing turnover, raising average engagement scores, or placing their employees into the required distribution of 70 percent in the middle, 10 percent at the bottom, and 20 percent in the top.

Figure 1-2. Hitting the “wall” in HR measurement.

Yet having business leader incentives based on HR measures is not the same as creating organization change. To have impact, HR measures must create a true strategic difference in the organization. Many organizations are frustrated because they seem to be doing all the measurement things “right,” but there is a large gap between the expectations for the measurement systems and their true effects. HR measurement systems have much to learn from measurement systems in more mature professions such as finance and marketing. In these professions, measures are only one part of the system for creating organizational change through better decisions.

Typically, HR develops measures to justify the investment in the HR function and its services and activities, or to prove a cause-effect connection between HR programs and organizational outcomes. Contrast this with financial measurement. Although it is certainly important to measure how the accounting or finance department operates, the majority of financial measures are not concerned with how finance and accounting programs and services are delivered. Financial measures typically focus on the outcomes—the quality of decisions about financial resources. Most HR measures today focus on how the HR function is using and deploying its resources and whether those resources are used efficiently. If the HR organization is ultimately to be accountable for improving talent decisions throughout the organization, HR professionals must take a broader and more complete perspective on how measurements can drive strategic change.

Correcting these limitations requires keeping in mind the basic principle expressed at the beginning of this chapter: Human capital metrics are valuable to the extent that they improve decisions about talent and how it is organized. That means that we must embed HR measures within a complete framework for creating organizational change through enhanced decisions. We describe that framework next.

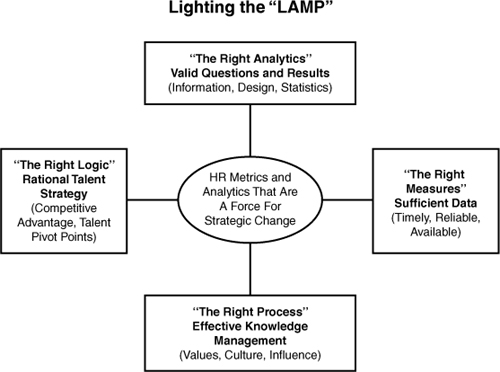

We believe that a paradigm extension toward a talent decision science is key to getting to the other side of the wall. Incremental improvements in the traditional measurement approaches will not address the challenges. HR measurement can move beyond the wall using what we call the LAMP model, shown in Figure 1-3. The letters in LAMP stand for logic, analytics, measures, and process, four critical components of a measurement system that drives strategic change and organizational effectiveness. Measures represent only one component of this system. Although they are essential, without the other three components, the measures and data are destined to remain isolated from the true purpose of HR measurement systems.

Figure 1-3. Lighting the LAMP.

The LAMP metaphor refers to a story that reflects today’s HR measurement dilemma:

One evening while strolling, a man encountered an inebriated person diligently searching the sidewalk below a street lamp.

“Did you lose something?” he asked.

“My car keys. I’ve been looking for them for an hour,” the person replied.

The man quickly scanned the area, spotting nothing. “Are you sure you lost them here?”

“No, I lost them in that dark alley over there.”

“If you lost your keys in the dark alley, why don’t you search over there?”

“Because this is where the light is.”

In many ways, talent and organization measurement systems are like the person looking for the keys where the light is, not where they are most likely to be found. Advancements in information technology often provide technical capabilities that far surpass the ability of the decision science and processes to use them properly. So it is not uncommon to find organizations that have invested significant resources constructing elegant search and presentation technology around measures of efficiency, or measures that largely emanate from the accounting system.

The paradox is that genuine insights about human resources often exist in the areas where there are no standard accounting measures. The significant growth in HR outsourcing, where efficiency is often the primary value proposition and IT technology is the primary tool, has exacerbated these issues.7 Even imperfect measures aimed at the right areas may be more illuminating than very elegant measures aimed in the wrong places.

Returning to our story about the person looking for keys under the street lamp, it’s been said, “Even a weak penlight in the alley where the keys are is better than a very bright streetlight where the keys are not.”

Figure 1-3 shows that HR measurement systems are only as valuable as the decisions they improve and the organizational effectiveness to which they contribute. HR measurement systems create value as a catalyst for strategic change. Let’s examine how the four components of the LAMP framework define a more complete measurement system. We present the elements in the following order: logic, measures, analytics, and, finally, process.

Logic: What Are the Vital Connections?

Without proper logic, it is impossible to know where to look for insights. The logic element of any measurement system provides the “story” behind the connections between the numbers and the effects and outcomes. In this book, we provide logical models that help to organize the measurements and show how they inform better decisions.

Most chapters provide “logic models” for this purpose. Examples include the connections between health/wellness and employee turnover, performance, and absenteeism in Chapter 5, “Employee Health, Wellness, and Welfare.” In Chapter 4, “The High Cost of Employee Separations,” on employee turnover, we propose a logic model that shows how employee turnover is similar to inventory turnover. This simple analogy shows how to think beyond turnover costs, to consider performance and quality, and to optimize employee shortages and surpluses, not just eliminate them. In Chapter 8, “Staffing Utility: The Concept and Its Measurement,” we propose a logic model that shows how selecting employees is similar to optimizing a supply chain for talent, to help leaders understand how to optimize all elements of employee acquisition, not simply maximize the validity of tests or the quality of recruitment sources. In Chapter 9, “The Economic Value of Job Performance,” we propose a logic model that focuses on where differences in employee performance are most pivotal, borrowing from the common engineering idea that improving performance of every product component is not equally valuable.

Another prominent logic model is the “service-value-profit” framework for the customer-facing process. This framework depicts the connections between HR and management practices, which affect employee attitudes, engagement, and turnover, which then affect the experiences of customers, which affect customer-buying behavior, which affects sales, which affect profits. Perhaps the most well-known application of this framework was Sears, which showed quantitative relationships among these factors and used them to change the behavior of store managers.8

Missing or faulty logic is often the reason well-meaning HR professionals generate measurement systems that are technically sound but make little sense to those who must use them. With well-grounded logic, it is much easier to help leaders outside the HR profession understand and use the measurement systems to enhance their decisions. Moreover, that logic must be constructed so that it is understandable and credible not only to HR professionals, but to the leaders they seek to educate and influence. Connecting HR measures to traditional business models in this way was described as Retooling HR, by John Boudreau, in his book of that name.9

Measures: Getting the Numbers Right

The measures part of the LAMP model has received the greatest attention in HR. As discussed in subsequent chapters, virtually every area of HR has many different measures. Much time and attention is paid to enhancing the quality of HR measures, based on criteria such as timeliness, completeness, reliability, and consistency. These are certainly important standards, but lacking a context, they can be pursued well beyond their optimum levels, or they can be applied to areas where they have little consequence.

Consider the measurement of employee turnover. Much debate centers on the appropriate formulas to use in estimating turnover and its costs, or the precision and frequency with which employee turnover should be calculated. Today’s turnover-reporting systems can calculate turnover rates for virtually any employee group and business unit. Armed with such systems, managers “slice and dice” the data in a wide variety of ways (ethnicity, skills, performance, and so on), with each manager pursuing his or her own pet theory about turnover and why it matters. Some might be concerned about losing long-tenure employees, others might focus on high-performing employees, and still others might focus on employee turnover where outside demand is greatest. These are all logical ideas, but they are not universally correct. Whether they are useful depends on the context and strategic objectives. Lacking such a context, better turnover measures won’t help improve decisions. That’s why the logic element of the LAMP model must support good measurement.

Precision is not a panacea. There are many ways to make HR measures more reliable and precise. Focusing only on measurement quality can produce a brighter light shining where the keys are not! Measures require investment, which should be directed where it has the greatest return, not just where improvement is most feasible. Taking another page from the idea of “retooling HR” to reflect traditional business models, organizations routinely pay greater attention to the elements of their materials inventory that have the greatest effect on costs or productivity. Indeed, a well-known principle is the “80-20 rule,” which suggests that 80 percent of the important variation in inventory costs or quality is often driven by 20 percent of the inventory items. Thus, although organizations indeed track 100 percent of their inventory items, they measure the vital 20 percent with greater precision, more frequency, and greater accountability for key decision makers.

Why not approach HR measurement in the same way? Factors such as employee turnover, performance, engagement, learning, and absence are not equally important everywhere. That means measurements like these should focus precisely on what matters. If turnover is a risk due to the loss of key capabilities, turnover rates should be stratified to distinguish employees with such skills from others. If absence has the most effect in call centers with tight schedules, this should be very clear in how we measure absenteeism.

Lacking a common logic about how turnover affects business or strategic success, well-meaning managers draw conclusions that might be misguided or dangerous, such as the assumption that turnover or engagement have similar effects across all jobs. This is why every chapter of this book describes HR measures and how to make them more precise and valid. However, each chapter also embeds them in a logic model that explains how the measures work together.

Analytics: Finding Answers in the Data

Even a very rigorous logic with good measures can flounder if the analysis is incorrect. For example, some theories suggest that employees with positive attitudes convey those attitudes to customers, who, in turn, have more positive experiences and purchase more. Suppose an organization has data showing that customer attitudes and purchases are higher in locations with better employee attitudes. This is called a positive correlation between attitudes and purchases. Organizations have invested significant resources in improving frontline-employee attitudes based precisely on this sort of correlation. However, will a decision to improve employee attitudes lead to improved customer purchases?

The problem is that such investments may be misguided. A correlation between employee attitudes and customer purchases does not prove that the first one causes the second. Such a correlation also happens when customer attitudes and purchases actually cause employee attitudes. This can happen because stores with more loyal and committed customers are more pleasant places to work. The correlation can also result from a third, unmeasured factor. Perhaps stores in certain locations (such as near a major private university) attract college-student customers who buy more merchandise or services and are more enthusiastic and also happen to have access to college-age students that bring a positive attitude to their work. Store location turns out to cause both store performance and employee satisfaction. The point is that a high correlation between employee attitudes and customer purchases could be due to any or all of these effects. Sound analytics can reveal which way the causal arrow actually is pointing.

Analytics is about drawing the right conclusions from data. It includes statistics and research design, and it then goes beyond them to include skill in identifying and articulating key issues, gathering and using appropriate data within and outside the HR function, setting the appropriate balance between statistical rigor and practical relevance, and building analytical competencies throughout the organization. Analytics transforms HR logic and measures into rigorous, relevant insights.

Analytics often connect the logical framework to the “science” related to talent and organization, which is an important element of a mature decision science. Frequently, the most appropriate and advanced analytics are found in scientific studies that are published in professional journals. In this book, we draw upon that scientific knowledge to build the analytical frameworks in each chapter.

Analytical principles span virtually every area of HR measurement. In Chapter 2, we describe general analytical principles that form the foundation of good measurement. We also provide a set of economic concepts that form the analytical basis for asking the right questions to connect organizational phenomena such as employee turnover and employee quality to business outcomes. In addition to these general frameworks, each chapter contains analytics relevant specifically to the topic of that chapter.

Advanced analytics are often the domain of specialists in statistics, psychology, economics, and other disciplines. To augment their own analytical capability, HR organizations often draw upon experts in these fields, and upon internal analytical groups in areas such as marketing and consumer research. Although this can be very useful, it is our strong belief that familiarity with analytical principles is increasingly essential for all HR professionals and for those who aspire to use HR data well.

Process: Making Insights Motivating and Actionable

The final element of the LAMP framework is process. Measurement affects decisions and behaviors, and those occur within a complex web of social structures, knowledge frameworks, and organizational cultural norms. Therefore, effective measurement systems must fit within a change-management process that reflects principles of learning and knowledge transfer. HR measures and the logic that supports them are part of an influence process.

The initial step in effective measurement is to get managers to accept that HR analysis is possible and informative. The way to make that happen is not necessarily to present the most sophisticated analysis. The best approach may be to present relatively simple measures and analyses that match the mental models that managers already use. Calculating turnover costs can reveal millions of dollars that can be saved with turnover reductions, as discussed in Chapter 4. Several leaders outside of HR have told us that a turnover-cost analysis was the first time they realized that talent and organization decisions had tangible effects on the economic and accounting processes they were familiar with.

Of course, measuring only the cost of turnover is insufficient for good decision making. For example, overzealous attempts to cut turnover costs can compromise candidate quality in ways that far outweigh the cost savings. Managers can reduce the number of candidates who must be interviewed by lowering their selection standards. The lower the standards, the more candidates will “pass” the interview, so fewer interviews must be conducted to fill a certain number of vacancies. Lowering standards can create problems that far outweigh the cost savings from doing fewer interviews! Still, the process element of the LAMP framework reminds us that often best way to start a change process may be first to assess turnover costs, to create initial awareness that the same analytical logic used for financial, technological, and marketing investments can apply to human resources. Then the door is open to more sophisticated analyses beyond the costs. Once leaders buy into the idea that human capital decisions have tangible monetary effects, they may be more receptive to greater sophistication, such as considering employee turnover in the same framework as inventory turnover.

Education is also a core element of any change process. The return on investment (ROI) formula from finance is actually a potent tool for educating leaders in the key components of financial decisions. It helps leaders quickly incorporate risk, return, and cost in a simple logical model. In the same way, we believe that HR measurements increasingly will be used to educate constituents and will become embedded within the organization’s learning and knowledge frameworks. For example, Valero Energy tracked the performance of both internal and external sources of applicants on factors such as cost, time, quality, efficiency, and dependability. It provided this information to hiring managers and used it to establish an agreement about what managers were willing to invest to receive a certain level of service from internal or external recruiters. Hiring managers learned about the tradeoffs between investments in recruiting and its performance.10 We will return to this idea in Chapters 8, 9, and 10.

In the chapters that follow, we suggest where the HR measures we describe can connect to existing organizational frameworks and systems that offer the opportunity to get attention and to enhance decisions. For example, organizational budgeting systems reflect escalating health-care costs. The cost measures discussed in Chapter 5, offer added insight and precision for such discussions. By embedding these basic ideas and measures into the existing health-care cost discussion, HR leaders can gain the needed credibility to extend the discussion to include the logical connections between employee health and other outcomes, such as learning, performance, and profits. What began as a budget exercise becomes a more nuanced discussion about the optimal investments in employee health and how those investments pay off.

As another example, leaders routinely assess performance and set goals for their subordinates. Measuring the value of enhanced performance can make those decisions more precise, focusing investments on the pivot points where performance makes the biggest difference. Chapter 9 describes methods and logic for measuring the monetary impact of improved performance.

You will see the LAMP framework emerge in many of the chapters in this book, to help you organize not only the measures, but also your approach to making those measures matter.

Conclusion

HR measures must improve important decisions about talent and how it is organized. This chapter has shown how this simple premise leads to a very different approach to HR measurement than is typically followed today, and how it produces several decision-science-based frameworks to help guide HR measurement activities toward greater strategic impact. We have introduced not only the general principle that decision-based measurement is vital to strategic impact, but also the LAMP framework, as a useful logical system for understanding how measurements drive decisions, organization effectiveness, and strategic success. LAMP also provides a diagnostic framework that can be used to examine existing measurement systems for their potential to create these results. We return to the LAMP framework frequently in this book.

We also return frequently to the ideas of measuring efficiency, effectiveness, and impact, the three anchor points of the talentship decision framework of Boudreau and Ramstad. Throughout the book, you will see the power and effectiveness of measures in each of these areas, but also the importance of avoiding becoming fixated on any one of them. As in the well-developed disciplines of finance and marketing, it is important to focus on synergy between the different elements of the measurement and decision frameworks, not to fixate exclusively on any single component of them.

We show how to think of your HR measurement systems as teaching rather than telling. We also describe the opportunities you will have to take discussions that might normally be driven exclusively by accounting logic and HR cost cutting, and elevate them with more complete frameworks that are better grounded in the science behind human behavior at work. The challenge will be to embed those frameworks in the key decision processes that already exist in organizations.

Software to Accompany Chapters 3–11

To enhance the accuracy of calculations for the exercises that appear at the end of each chapter and make them easier to use, we have developed web-based software to accompany material in Chapters 3–11. The software covers the following topics:

• Employee absenteeism

• Turnover

• Health and welfare

• Attitudes and engagement

• Work-life issues

• External employee sourcing

• The economic value of job performance

• Payoffs from selection

• Payoffs from training (HR development)

Developed with support from the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), you can access this software from the SHRM website (http://hrcosting.com/hr/) anywhere in the world, regardless of whether you are a member of SHRM. Of particular note to multinational enterprises, the calculations can be performed using any currency, and currency conversions are accomplished easily. You can save, print, or download your calculations and carry forward all existing data to subsequent sessions. Our hope is that, by reducing the effort necessary to perform the actual calculation of measures, readers will spend more time focusing on the logic, analytics, and processes necessary to improve strategic decisions about talent.

References

1. Colvin, G., “How Are Most Admired Companies Different? They Invest in People and Keep Them Employed—Even in a Downturn,” Fortune (22 March 2010): 82.

2. Boudreau, J. W., and P. R. Ramstad, Beyond HR: The New Science of Human Capital (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business Press, 2007).

3. Rynes, S. L., A. E. Colbert, and K. G. Brown, “HR Professionals’ Beliefs About Effective Human Resource Practices: Correspondence Between Research and Practice,” Human Resource Management 41, no. 2 (2002): 149–174. See also Rynes, S. L., T. L. Giluk, and K. G. Brown, “The Very Separate Worlds of Academic and Practitioner Publications in Human Resource Management: Implications for Evidence-Based Management,” Academy of Management Journal 50, no. 5 (2007): 987–1008.

4. Briner, R. B., D. Denyer, and D. M. Rousseau, “Evidence-Based Management: Concept Cleanup Time?” Academy of Management Perspectives 23, no. 4 (2009): 19–32.

5. This section draws material from Chapter 9 in Boudreau and Ramstad, Beyond HR (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

6. Lawler, E. E. III, A. Levenson, and J. W. Boudreau, “HR Metrics and Analytics—Uses and Impacts,” Human Resource Planning Journal 27, no. 4 (2004): 27–35.

7. Cook, M. F., and S. B. Gildner, Outsourcing Human Resources Functions, 2nd ed. (Alexandria, Va.: Society for Human Resource Management, 2006). See also Lawler, E. E. III, D. Ulrich, J. Fitz-enz, and J. Madden, Human Resources Business Process Outsourcing (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2000).

8. Rucci, A. J., S. P. Kirn, and R. T. Quinn, “The Employee-Customer-Profit Chain at Sears,” Harvard Business Review (January–February 1998): 83–97.

9. Boudreau, John W., Retooling HR: Using Proven Business Models to Improve Decisions About Talent (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business Publishing, 2010).

10. Boudreau, Retooling HR, Chapter 5.