1. Business Strategy, Financial Strategy, and HR Strategy

What makes one company more successful than another? Is it because it has nicer office buildings, newer research labs, or better manufacturing equipment? If it is the differences in people that create differences in corporate value, then the HR function (though not necessarily the HR department) is critical to a corporation’s success. Clearly line managers have an important role in hiring, developing, and motivating the people that can make an organization successful. Perhaps surprisingly it is the role of human resource managers in this process that is less clear. Should human resource managers have primarily an administrative role focusing on the processing of transactions and compliance with regulations? Should human resource managers be business partners charged with developing and maintaining a workforce with the specific capabilities required to execute their firm’s business strategy? Or should human resource managers be true strategic partners participating along with top management, and their counterparts from other functional areas, in the actual development and monitoring of a firm’s business strategy? In many organizations HR departments play only one or two of these three roles. It is a premise of this book that many firms fail to achieve their maximum success because they do not utilize their HR departments optimally. It must be acknowledged, however, that line managers may be underutilizing their HR departments because they are not confident that HR can perform at higher levels.

Is HR Weakest in the Most Critical Areas?

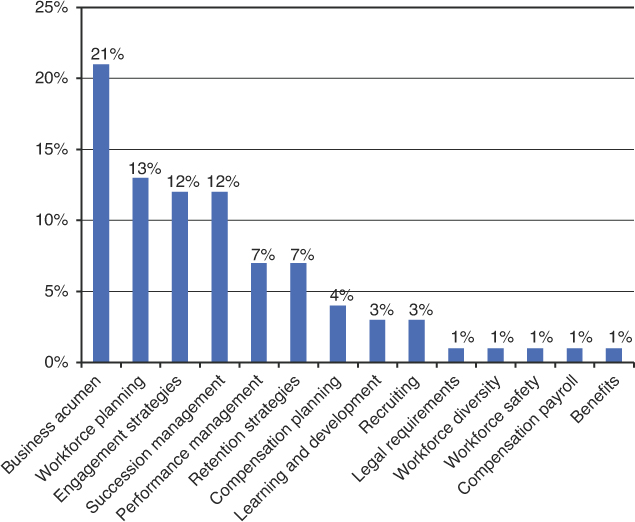

A study conducted by the Corporate Leadership Council (CLC)1 found that in the opinion of the 16,000 line managers who were surveyed, fewer than one in five HR business partners were highly effective in their strategy roles. That’s a statement that the HR profession should find troubling. The good news is that there’s lots of room for improvement, and we know how to generate those improvements. The CLC study also estimated the relationship between HR staff competencies and degree of success as a strategic partner. Their findings are summarized in Exhibit 1-1. Each vertical bar represents an estimate of the maximum impact on strategic role effectiveness of a particular HR capability. The maximum impact was calculated by comparing the strategic role performance of individuals rated high and individuals rated low on each capability. Of far greater importance than expertise in any HR specialization was overall business acumen. What are the implications of that statement for the way you select and train HR professionals? Does it mean you don’t need individuals with specialized training or experience in HR? No, but it suggests that while specialized HR skills are necessary, they are not sufficient.

Exhibit 1-1. Impact of HR competencies on strategic role effectiveness

Source: Graph created using data from Corporate Leadership Council, “Building Next-Generation HR-Line Partnerships,” Corporate Executive Board, 2008, p. 32.

HR professionals need both HR knowledge and a high degree of business acumen. Most individuals in the field today have strong HR skills. There is, however, a wide range in the level of business acumen they possess. That creates substantial competitive advantages for corporations whose HR staffs possess both sets of skills. For individuals who have both sets of skills, it also creates great opportunities for them to advance within their HR careers. The specific mix of skills required depends, of course, on the individual’s job duties and position in the corporate hierarchy. In general, the higher the individual is (or hopes to be) in the corporate hierarchy, the greater the need for strong business acumen to complement their HR knowledge.

What is business acumen, anyway? At the most fundamental level, it is an understanding of how your company makes money and how your decisions and behaviors can impact the company’s financial performance. The business acumen needed by HR managers includes an understanding of their firm’s business strategy, the key drivers of their firm’s success, and the interrelationships among the different components of the organization. This understanding is necessary to develop and execute an effective HR strategy. There is no business department, function, or activity whose success is not dependent upon the firm’s HR strategy. An organization’s HR strategy determines who is employed in each functional area, how much will be invested to enhance their skills and capabilities, and what behaviors will be encouraged or discouraged through the compensation system. A firm’s HR strategy must be tailored to support its business strategy. To produce this alignment, HR managers need the ability to analyze which choices will add value to the firm and which will weaken it. Do most individuals in the HR profession have that ability? In a survey conducted by Mercer Consulting,2 HR leaders were asked to assess the skills of their staffs. They rated their staffs weakest on the following skill sets:

• Financial skills

• Business strategy skills

• Organizational assessment

• Cross-functional expertise

• Cost analysis and management

They felt their staffs were strongest at the following:

• Interpersonal skills

• Recordkeeping/data maintenance

• Team skills

• Functional HR expertise

• Customer service

The skill sets where these HR staffs were strong are important, but they are not the skill sets that drive corporate success or the career success of individual HR managers. No company is going to become an industry leader because of the interpersonal skills or recordkeeping abilities of its HR staff. It is rather striking that the areas in which these HR staffs were weakest are exactly the skill sets that are most likely to contribute to a corporation’s success, and exactly the skills that individual HR managers need to progress in their careers.

You Don’t Need to Be a Quant to Make Good Business Decisions

In most cases HR managers need only a modest level of quantitative skills. There is certainly no need to be the kind of individual the Wall Street firms refer to as a quant. Analyzing business decisions generally requires no more than a tolerance for basic arithmetic and a comfort with the creation and use of spreadsheets. Actually, in many cases more important than the ability to crunch the numbers is the ability to think analytically and creatively about the business challenges a firm faces. Some HR managers are limited in their ability to do this simply because they do not understand all the jargon used in their company’s financial statements or in the models their firm uses to evaluate business alternatives. Without that understanding it’s impossible to know, for example, whether a proposal made by a colleague is brilliant or nonsense.

Fortunately, gaining an understanding of basic financial jargon and concepts is not difficult to do. You don’t need a degree in finance to use financial tools to make better decisions. The goal of this book is to help HR professionals deepen their understanding of business economics and finance. Hopefully an increased understanding of these issues can enable them to make better decisions about resource allocations within the HR function. The bigger potential benefit, however, is that an increased understanding of these issues can enable them to more effectively tailor an HR strategy to the firm’s business strategy. If this can be done they can significantly improve their firm’s competitiveness and add value to the firm’s shareholders. At the same time they can enhance their own prospects for career advancement. Too many HR professionals underestimate the role HR can and should play in strategic decisions. They should not be deterred simply because these decisions involve financial models or analyses.

Which HR Decisions Are Important?

In many organizations, human resource costs (recruitment, selection, compensation, training, and workforce administration) are the largest component of the firm’s operating expenses. In some service organizations these items constitute 70% to 80% of the firm’s total costs. Properly managing those costs is therefore critical to the success of any corporation. Other things equal, a 10% reduction in a firm’s HR costs can produce a huge increase in its bottom line profit. Still, of greater importance than managing workforce costs is creating workforce value. Firms do not become industry leaders because they have the lowest turnover rate, the smallest health insurance premiums, or the lowest cost per hire. Firms succeed because they create value for their customers. Firms succeed because they have a workforce that skillfully executes a value-creating business strategy. A firm’s objective must be to maximize the return on the investment (ROI) it makes in its workforce. The relationship between the ROI and HR costs can be summarized as: HR ROI = Workforce value / HR costs. Yes, other things equal, reducing HR costs in the denominator of this ratio produces an increase in ROI. Of course, increasing HR costs in the denominator of this ratio could also improve ROI. That would be the case when these additional HR expenditures result in even larger increases in workforce value.

Reducing inefficiencies in HR processes and increasing workforce value are both important. Increases in workforce value, however, are most likely to explain a firm’s level of success. Consider these two firms. Company A’s management and workforce are by far the most talented and engaged in the industry. Company B’s management and workforce are about average for the industry, but its cost per hire is much less than average. Which HR department is doing the better job? In which firm will more value be created for shareholders? The amount a firm can save by reducing inefficiencies in HR processes is usually insignificant compared to the amount it can gain by building a more talented and engaged work force. Of course if you can do both, you should. Several books have been written that focus on using financial tools to improve the efficiency of resource allocation within the HR department. This book discusses those issues but focuses on the financial understanding needed to align HR strategy with business strategy and create shareholder value.

What This Book Attempts to Do

When should financial analyses precede HR decisions? The answer to that question is always. That doesn’t mean that in all cases you need to develop spreadsheet models and utilize their built-in financial functions. That may be necessary when decisions involve many factors or substantial amounts of money. However, even in situations in which no formal modeling is warranted, you need to consider the potential financial implications of your recommendations and actions. To do that requires an understanding of and appreciation for the importance of the following:

• Basic financial concepts such as the difference between profit and cash flow

• Difference between the market value and the book value of a company

• Cost of capital

• Time value of money

• Return on investment

• Risk reward trade-offs

• Risk management tools such as diversification and real options

Most of these concepts are just as relevant for your personal decision making as for your decisions at work. HR managers also need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the various financial performance measures used to assess how well a company is doing and as a basis for allocating incentive pay.

This book provides you with an intuitive understanding of each of these topics. Algebraic notation and equations are avoided, and these concepts are illustrated using spreadsheet examples. Not all HR managers are comfortable with algebraic notation, and in any case spreadsheets are the format in which they are most likely to encounter these concepts on the job. Where appropriate the keystrokes for utilizing Microsoft Excel’s built-in financial functions are provided and discussed. This book does not attempt to include an introduction to the HR strategy or to corporate compensation policies. There are excellent volumes devoted to these topics.3 What it does attempt to do is provide HR managers with an understanding of the financial jargon and methods often central to strategy development and compensation policy.

Chapter 2 (“The Income Statement: Do We Care About More Than the Bottom Line?”), Chapter 3 (“The Balance Sheet: If Your People Are Your Most Important Asset, Where Do They Show Up on the Balance Sheet?”), and Chapter 4 (“Cash Flows: Timing Is Everything”) use data from the annual reports of Home Depot, Inc., to review the interpretation of corporate income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements. If you are familiar with the interpretation of basic financial statements and the differences between profit and cash flow, you may want to skip over these chapters. Chapter 5 (“Financial Statements as a Window into Business Strategy”) provides a case study on using financial statements to gain insights into a firm’s business strategy. Chapter 6 (“Stocks, Bonds, and the Weighted Average Cost of Capital”) and Chapter 7 (“Capital Budgeting and Discounted Cash Flow Analysis”) discuss the concepts of cost of capital and time value of money. Chapter 8 (“Financial Analysis of Human Resource Initiatives”) uses these concepts to look at resource allocation within the HR function. Chapter 9 (“Financial Analysis of Corporation’s Strategic Initiatives”) begins with the premise that if HR managers are going to be true strategic partners they must understand the financial models used to develop and evaluate corporate strategy. These techniques are discussed in spreadsheet illustrations. Chapter 10 (“Equity-Based Compensation: Stock and Stock Options”) looks at equity pay and the implications of paying in stock versus paying in stock by stock options. Pensions are of enormous financial significance to the U.S. economy and to most large corporations, and they are the subject of Chapter 11 (“Financial Aspects of Pension and Retirement Programs”). The chapter includes a discussion of the way pension accounting choices can affect the company’s bottom line profit. Chapter 12 (“Creating Value and Rewarding Value Creation”) attempts to pull all these concepts together to look at the conditions under which shareholder value is created and at the strengths and weaknesses of alternative measures of value creation. These topics are discussed within the context of incentive pay and the choice of performance metrics that encourage the development and execution of strategies that create long-term value for the firm and its stakeholders.