1

Knowledge management and learning

for organizations

Many practices attempting to manage individual and corporate learning have over time converged into what is now labelled ‘knowledge management’. A number of disciplines have been involved in this evolution, ranging from psychology to management. This diversity has culminated in the development of a range of terms such as ‘the learning organization’, ‘intellectual capital management’, ‘intellectual asset management’ and ‘knowledge management’.

From these beginnings it is easy to conclude that the modern conceptualization of knowledge management is an umbrella for capturing a range of organizational concerns. Irrespective of the precise terminology, there fortunately is common understanding that knowledge management encapsulates a more organic and holistic way of understanding and leveraging people within work processes for business benefit.

Emergence of knowledge management

Whatever the label given to managing knowledge and organizational learning, during the 1980s the importance of managing knowledge in business started to take-off. With leading edge examples set by a small number of multinational companies and consultancies, others soon began to appreciate that managing knowledge effectively provided competitive advantage in an increasingly competitive and dynamic business environment. By the mid to late 1990s there emerged a significant interest in knowledge management. Companies began to realize that inside their own organizations lay untapped pools of knowledge, knowhow and best practices, which they had thus far failed to employ or even recognize. In an Ernst & Young 1997 survey (Ruggles, 1998), 94 per cent of respondents indicated that they could leverage the knowledge in their organizations more effectively through a more deliberate approach to knowledge management. Over 40 per cent reported they had already started or completed a knowledge management project. Supporting this trend, another survey (KPMG Management Consulting, 1998) of 100 senior executives highlighted that 79 per cent of respondents described their businesses as managing knowledge to some greater or lesser degree. The insight that companies can benefit by applying a more structured and conscious approach to managing knowledge provided it with a strong push onto the corporate agenda.

It was not long before managers began to ask how to leverage knowledge to enhance business success. Indeed, a very large proportion of managers (87 per cent) started to describe their businesses as knowledge intensive (Ernst and Young Centre for Business Innovation and Business Intelligence, 1997). The prevalence of these beliefs led many companies to develop more structured and conscious ways for managing learning and knowledge. Soon thereafter, many began to see management of knowledge and learning as a core competency, fundamental to sustaining competitive advantage. Successful knowledge management programmes highlighted numerous potential benefits, such as:

- improved innovation leading to improved products and services

- improved decision making

- quicker problem solving and fewer mistakes

- reduced product development time

- improved customer service and satisfaction

- reduced research and development costs.

Interest in knowledge management can be divided into two broad camps: academic and practitioner. Academics have been heavily occupied with defining and classifying what constitutes knowledge (Fahey and Prusak, 1998), discussing the knowledge-based view of the organization (Spender, 1996) and so on. This debate received a major push when Nonaka (1994), in his now seminal work, declared that organizations wishing to become strategically innovative must move beyond the traditional model of processing information to one which incorporates the creation and management of knowledge.

The practitioner community, on the other hand is far more interested in pragmatic outcomes (Davenport and Klahr, 1998) – particularly, ways of leveraging knowledge to develop competitive strength for the organization (Earl and Scott, 1999). Capturing and implementing best practices is one of the major reasons why companies would consider engaging in management of knowledge and learning. We will examine, in our discussion, whether knowledge management ‘best practices’ exist, and if so what these are, by elaborating and reflecting upon the experience of numerous companies in the case studies presented in Part Two.

Before moving on, it is as well to note that while a large number of organizations have stated that their objective is to manage knowledge, many of them have not fully understood the problems, opportunities, strategies or solutions required to do so. Managing learning and knowledge requires more than small-time tinkering within the organization. Success demands a paradigm shift in organizational thinking.

Reflections on the importance of knowledge

While knowledge management has become rather fashionable in the 1990s, recognition of its importance precedes current-day interest. Edith Penrose in analysing the economics of the firm commented on the difficulty of managing the process: ‘Economists have, of course, always recognized the dominant role that increasingly knowledge plays in economic processes, but have, for the most part, found the whole subject of knowledge too slippery to handle’ (Penrose, 1959).

Herbert A Simon insightfully declared that knowledge is more than technology: ‘In the period ahead of us, more important than advances in computer design will be the advances we can make in our understanding of human information processing, of thinking, problem solving, and decision making …’ (Simon, 1968). Moreover, interest in knowledge management was not just confined solely within the domain of academic discourse but alluded much more popularly, as the quote from H. G. Wells highlights:

An immense and ever-increasing wealth of knowledge is scattered about the world today; knowledge that would probably suffice to solve all the mighty difficulties of our age, but it is dispersed and unorganised. We need a sort of mental clearinghouse for the mind: a depot where knowledge and ideas are received, sorted, summarised, digested, clarified and compared.

(Wells, 1940)

Scholars and observers from diverse perspectives, sociology, economics and management science, agree that managing knowledge is a fundamental driver of organizational progress in the modern business environment. Harvard sociologist, Bell (1973) presented one of the earliest analyses of the changes that might accompany the increase in knowledge use. Stanford economist, Romer (1990), published the first quantitatively rigorous treatment of how the use of knowledge affects economic growth. Management guru, Drucker (1993), provided a historical perspective of how recent economic changes could be framed within a business context.

The trend over time has been for knowledge-based firms to move towards precognition and adaptation. This is in stark contrast to the traditional emphasis on optimization. This trend is amplified by two facilitating factors: speed and interconnection. All these elements intertwine for future organizational success. Speed, in the form of transmission of information and knowledge, quicker decision making and innovation cycles, together with interconnection of information systems, workers, organizations and economies, facilitates precognition and adaptation. Castells (1996) summarizes the shift as follows: ‘What characterises the current technological revolution is not the centrality of knowledge and information but the application of such knowledge and information to knowledge generation, information processing, communication devices, in a cumulative feedback loop between innovation and the uses of innovation.’

Companies are facing up to this new reality. The modern business economy does not favour organizational competencies that have provided historic business success. The new era demands new formats and new strategies, and managing learning and knowledge rests central within these.

Towards new approaches for competitive advantage

Traditional concepts

Organizations exist because collaboration of resources can yield higher outcomes than an individual alone. Argyris and Schon (1978) note that a collection of individuals becomes an organization when the individuals start to act for the good of the organization. The organizational collective is awarded identity by the actions of the individuals it comprises.

Henri Fayol, in the early twentieth century, was the founder of the administrative school of management. He divided the company into six functional departments: technical, commercial, financial, security, accounting and managerial. These divisions came about prior to modern thinking on marketing and sales. Fayol (1919) was one of the first people to demonstrate the concept of an ultimate system of operation for an organization. At about the same time a German psychologist, Max Weber, developed a series of rules for efficient organization (Weber, 1924). He proposed that a hierarchy should be developed, and positions in that hierarchy should be awarded on merit. Additionally, he suggested that organizations should be divided into parts, with a clear specification for each part. Both of these theories have merit but are somewhat outdated, having been formulated in an era when the turbulence and turmoil we see daily in business today was virtually non-existent. A particular weakness in companies basing their structures on the edifice of these theories is that they become cast in an inflexible mould, finding it difficult to change in the face of external forces.

The business historian and analyst, Alfred D. Chandler, argued in the 1960s that the structure of an organization governs the effectiveness of its use of resources. Therefore company strategies should reflect not only the use of resources, but also the specific goals the company is trying to achieve. Igor Ansoff, the strategy theorist, built on this notion by suggesting that the use of resources was to be maximized prior to the matching of business opportunities with organizational resources (Ansoff, 1988). In short, he believed in maximizing strengths and minimizing weaknesses. However, both these approaches produce a company with distinct strengths that are difficult to change if the market moves on (as it inevitably does). Some of Ansoff's later work focused on ‘paralysis by analysis’, showing such organizations to be too rigid and slow to adapt to change.

In the 1980s, Porter developed a framework for the analysis of competitive strategy (Porter, 1985). It focused on the view of an organization as an entity driven by reactions to its external environment. Porter identified five forces relevant to company success or failure and suggested that strategy should be formulated by the organization to deal with these. The five forces are:

1 The potential of new entrants to the market.

2 The bargaining power of customers.

3 The threat of substitute products.

4 The bargaining power of suppliers.

5 The activities of existing competitors.

Each factor can affect profitability, and this profitability determines what is the most effective and appropriate strategy. In later work, Porter linked internal, or corporate, resources with the external environment by explicating the concept of the value chain (Porter, 1985). The value chain is the chain of business operations that the organization must control and configure to construct a coherent competitive strategy. It includes management of such things as such as logistics, marketing, production and sales, and support functions such as human resources and technical infrastructure. Porter argues that a firm gains competitive advantage by performing these value-chain activities more cheaply, more effectively or in a better way than the competition.

Developing knowledge management and learning as core competencies

It is the management of internal or corporate resources that with which we are most concerned. While market economic theory takes the view of scarcity of resources, organizational theory assumes that the same external resources are available to all. Therefore, only better internal resources can make a difference to achieving a competitive advantage over the competition, i.e. internal resources must perform better than the competition. Internal resources are assets such as the human resources or machinery belonging to a particular organization. These assets must perform its task more effectively than the competition.

Prahalad and Hamel (1990) extend this view in defining the notion of core competencies, which are responsible for competitive advantage. Moreover, to build and sustain competitive advantage the core competencies must be difficult to imitate, non-substitutable, durable and non-transparent (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991). Some of these core competencies are not independent – other factors come into play when you depart from the theoretical world and move into the real world: Itami (1987) stated that irreversible assets were divided into tangible and intangible sources of profits; Collis (1996) built on the work of Teece, Pisano and Shuen (1994) in identifying organizational capability as the firm's dynamic routines that enable it to generate continuous improvement in efficiency or effectiveness, and that it embodied the firm's tacit knowledge of how to initiate or respond to change. From this perspective, the organizational capability of managing knowledge and learning is deemed a core competence.

It is in the science of developing core competencies that organizational learning and knowledge management is most intimately associated. In order for a resource to yield competitive advantage the firm must utilize it in a unique way, or have some unique knowledge about its function. A prime example of a company attaining a competitive advantage is the development of a new product that is patentable. Once patent protected, the product can produce a profit stream. If we look back at how that product was developed we can see that a systematic analysis of a market or a customer need produced the concept or design for that product. There are several systematic ways of generating such concepts or ideas in line with the customer's requirements. It is the basic premise of organizational learning that such insight or process is applied to other aspects of the organization's function in order to generate a better or more efficient way of operating. The process described in this example, at a theoretical level, can be described as the management of knowledge for marketplace advantage.

Defining knowledge and knowledge management

Data, information and knowledge

To be able to manage knowledge, managers need a clear understanding of the nature and characteristics of knowledge. Knowledge is a multifaceted construct and is difficult to come to grips with. One of the most common starting points towards a definition is to distinguish between data, information and knowledge. Data can be described as a series of meaningless outputs from any operation. Data is the symbolic representation of numbers, letters, facts or magnitudes and is the means through which information and knowledge is stored and transferred. Information is the grouping of these outputs and placing of them in a context that makes a valuable output. Information is data arranged in meaningful patterns. Knowledge involves the individual combining his or her experience, skills, intuition, ideas, judgements, context, motivations and interpretation. It involves integrating elements of both thinking and feeling. According to Drucker (1989): ‘Knowledge is information that changes something or somebody, either by becoming grounds for actions, or by making an individual (or an institution) capable of different or more effective action.’ This suggests that knowledge is personal and intangible in nature, whereas information is tangible and available to anyone who cares to seek it out.

Knowledge and information are distinct entities. Information contained in computer systems is not a very rich vessel of human interpretation, which is necessary for potential action. Knowledge is in the user's subjective context of action, which is based on information that he or she possesses. Hence, knowledge resides in the user and not in the collection of information – what really matters is how the user reacts to the collection of information (Churchman, 1971).

While knowledge and information may be difficult to distiguish at times, both are more valuable than raw data. Knowledge starts off with an information base, but it is the intelligence added to that information that converts it into knowledge. Unfortunately, organizations have tended in the recent past to expend their energies in data capture and storage rather than knowledge creation and use. This has been the downside of the information technology revolution (see ‘The role of technology in knowledge management’ in this chapter).

Types of knowledge: tacit versus explicit

Polanyi's (1966) now famous statement, ‘we know more than we can tell’ highlights that much of what constitutes human skill remains unarticulated and known only to the person who has the skill. Polanyi went on to define two types of knowledge: explicit and tacit.

- Tacit knowledge is that which is very difficult to describe or express. It is the knowledge which is usually transferred by demonstration, rather than description, and encompasses such things as skills.

- Explicit knowledge is that which is easily written down or codified. It is relatively easy to articulate and communicate, and is easier to transfer between individuals and organizations. Explicit knowledge resides in formulae, textbooks or technical documents.

In contrast to explicit knowledge, tacit knowledge cannot be explicated fully even by an expert. It is transferred from one person to another only through a long process of apprenticeship (Polanyi, 1966). Tacit knowledge is work-related practical knowhow that is learned informally on the job (Wagner and Sternberg, 1987). Although initially conceived at the individual level, tacit knowledge exists in organizations as well. For example, Nelson and Winter (1982) point out that much organizational knowledge remains tacit because it is impossible to describe all aspects necessary for successful performance.

Analogous to the tacit and explicit dichotomy, Zuboff (1988) makes a distinction between embodied, or action-centred skills, and intellective skills. Action-centred skills are developed through actual performance (learning by doing). In contrast, intellective skills combine abstraction, explicit reference and procedural reasoning, which make them easily representable as symbols, and therefore easily transferable.

Organizations have traditionally focused on the explicit part of knowledge while ignoring tacit knowledge although it has been estimated that only 10 per cent of an organization's knowledge is explicit (Grant, 1996; Hall, 1993). One major reason why tacit knowledge is rarely managed is because it is much more difficult to manage. It involves extraction of personal knowledge which is difficult to express and communicate (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). It is deeply embedded within individual experience, judgement and intuition involving highly impenetrable intangibles such as personal beliefs, perspectives and the individual's value system. Yet, the success of any knowledge and learning programme to produce the much vaunted competitive advantages depends heavily on how well the organization manages its tacit knowledge. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) tacit knowledge lies at the very heart of organizational knowledge.

Knowledge characteristics

Knowledge is a multi-trait complex phenomenon. It possesses a number of interesting idiosyncrasies (Day and Wendler, 1998). These are presented below:

1 Knowledge is ‘sticky’. Some knowledge can be codified, but because tacit knowledge is embedded in people's minds, it is often ‘sticky’ as it tends to stay in people's heads. Even with modern tools, which can quickly and easily transfer information from one place to another, it is often very difficult and slow to transfer knowledge from person to person, since those who have knowledge may not be conscious of what they know or how significant it is. As knowledge is ‘sticky’, it often cannot be owned and controlled in the way that plant and equipment can.

2 Extraordinary leverage and increasing returns. Network effects can emerge as more and more people use knowledge. These users can simultaneously benefit from knowledge and increase its value by adding, adapting and enriching the knowledge base. Knowledge assets can grow in value as they become a standard on which others can build. This is unlike traditional company assets that decline in value as more people use them.

3 Fragmentation, leakage and the need for refreshment. As knowledge grows, it tends to branch and fragment. Today's specialist skill becomes tomorrow's common standard as fields of knowledge grow deeper and more complex. While knowledge assets can grow more and more valuable, others like expiring patents or former trade secrets can become less valuable as they are widely shared.

4 Knowledge is constantly changing. New knowledge is created every day. Knowledge decays and gets old and obsolete. Thus, it is hard to find and pinpoint knowledge.

5 Uncertain value. The value of an investment in knowledge is often difficult to estimate. Results may not come up to expectations. Conversely they may lead to extraordinary knowledge development. Even when knowledge investments create considerable value, it is hard to predict who will capture the lion's share of it.

6 Most new knowledge is context specific. Knowledge is usually created in practice for a particular use, and as such is context specific. Therefore the question is, what aspect of it can be transferred? This would suggest that concepts such as ‘best practice’ are of limited use.

7 Knowledge is subjective. Due to its subjective nature, not all employees might agree that specific knowledge is usable or best practice.

Knowledge management

In sum, we can conclude that knowledge management is as a complex, multi-layered and multifaceted concept. This is demonstrated by the number of differing opinions about the essence of knowledge management, which is reflected by the fact that there is no universally agreed definition of knowledge management. Nevertheless, most agree it is something to do with the systematic management of knowledge to achieve business benefits.

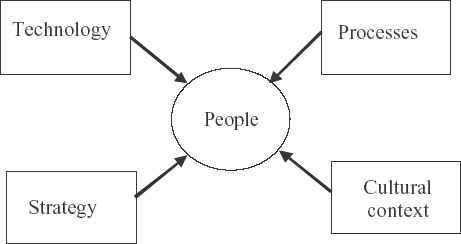

On the basis of the discussion, we propose that knowledge management is the coming together of organizational processes, information processing technologies, organizational strategies and culture for the enhanced management and leverage of human knowledge and learning to the benefit of the company (see Figure 1.1).

Knowledge management is not a separate management function or a separate process. Knowledge management consists of a set of cross-disciplinary organizational processes that seek the ongoing and continuous creation of new knowledge by leveraging the synergy of combining information technologies, and the creative and innovative capacity of human beings. To bring about business benefits, knowledge management has to be aligned to the company's strategic thrust. Indeed, if knowledge management is a ‘new’ organizational paradigm, it is only so in the sense that attempts are now being made to systematically manage it.

Fig. 1.1 Key elements in knowledge management

The role of technology in knowledge management

Managing knowledge creation requires getting individuals and teams to share information, experience and insight. New technologies facilitate this process. In the knowledge-creation process companies must tackle two key activities: collection and connection. The connecting dimension involves linking people who need to know with those who do know, and so developing new capabilities for nurturing knowledge and acting knowledgeably. Connecting is necessary because knowledge is embodied in people, and in the relationships within and between organizations. In carrying out collection and connection the company must achieve a balance of the two.

For many managers the rapidly falling costs of communications and computing, together with the growth and accessibility of the World Wide Web, has been instrumental in catalysing opportunities for knowledge sharing (Davenport and Prusak 1988). The best information environments make it easier for people to work together irrespective of geographic location and time. They do this by providing immediate access to the organizational knowledge base and thus create value to the user. For example:

- Electronic networks can give access to experts on a worldwide basis.

- Teams can work together without being together.

Information becomes knowledge through interpretation and is made concrete in the light of the individual's understandings of the particular context. For example, help desks and advisory services can be very effective, in the short term, in connecting people and getting quick answers to questions, thus accelerating cycle time and adding value for clients. Organizational ‘yellow pages’ can enable staff to connect to the right people and their know-how more efficiently. However, an organization that focuses entirely on connecting, with little or no attempt at collecting, can be very inefficient. Such organizations fail to get full leverage of sharing, and spend much time in ‘reinventing wheels’.

The collecting dimension relates to the capturing and disseminating of know-how. Information and communication technologies facilitate codification, storage and retrieval of content. Through such collections of content, what is learned is made readily accessible to future users. However, even where comprehensive collections of materials exist, effective use still requires knowledgeable and skilled interpretation and alignment with the local context to get effective results. This occurs through people. Therefore, organizations which concentrate completely on collecting and make little or no effort to foster people connections end up with a repository of static documents. Knowledge management programmes must aim to have an integrated approach to managing knowledge. This can be achieved through a balance between connecting individuals who need to know with those who do know, collecting what is learned as a result of these connections and making that easily accessible to others. For example, if collected documents are linked to their authors and contain other interactive possibilities, they can become dynamic and, hence, much more useful.

No matter how great their information processing capabilities, perhaps what is clear is that computers are merely tools (Strassman, 1998). Peter Drucker contends that the confusion between knowledge and information has caused managers to sink billions of dollars in information technology ventures that have yielded marginal results (Drucker, 1995). John Seely-Brown (1997), supports this view in that, in the last twenty years, US industry has invested more than $1 trillion in technology but has realized little improvement in the efficiency or effectiveness of its knowledge workers. Seely-Brown attributes this failure to organizations’ ignorance of ways in which knowledge workers communicate and operate. Knowledge is actually created not through technology but, rather, through the social processes of collaborating, sharing knowledge and building on each other's ideas.

Unfortunately, most conceptions of information technology (IT) do not adequately address the human aspects of knowledge, particularly the tacit dimension (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). Interpretations of knowledge management based primarily on rules and procedures embedded in technology seem misaligned with a dynamically changing business environment. In this sense, IT systems have hampered the management of knowledge because IT management has led to an inward focus to the exclusion of changes in the external reality of business (Drucker, 1993).

Defining learning

Types of learning: adaptive versus generative

Experts in the field of knowledge generation, Argyris and Schon, in their book Organisational Learning (Argyris and Schon, 1978), take the stance that there exists two types of learning: adaptive or generative. Adaptive learning, or single-loop learning, focuses on solving problems without examining the appropriateness of current learning behaviours (Argyris, 1992). Adaptive organizations focus on incremental improvements, often based upon their past track record of success. Essentially, they do not question the fundamental assumptions underlying the existing ways of doing work. This view is about coping.

Increasing adaptability is only the first stage of organizational learning. The next level is double-loop learning, or generative learning, which should be the main preoccupation for companies (Argyris, 1992). Double-loop learning emphasizes continuous experimentation and feedback in an ongoing examination of the very way organizations go about defining and solving problems. The essential difference between the two views is between being adaptable and having adaptability. To maintain adaptability, organizations need to operate as experimenting or self-designing organizations, i.e. they need to maintain themselves in a state of frequent, nearly continuous change (in structures, processes, domains, goals, etc.), even in the face of apparently optimal adaptation (Hedberg, Nystrom and Starbuck, 1976).

For example, single-loop learning is that imparted from a mentor to an apprentice, i.e. a technician can impart to another how to fix a carburettor. However, there is a deeper understanding to be had about the performance of the carburettor and, indeed, how the problem of its malfunction occurred in the first place. This understanding usually comes about after a large amount of experience of, and investigation into, the problem. The research may then be augmented with the knowledge that was not present when the item was designed, i.e. the particular nature of the failure. Therefore, the individual has questioned existing preconceptions and frameworks in order to come up with an improved solution. He or she has taken a wider view than that normally taken by a technician and questioned the specific paradigms upon which his or her day-to-day work has rested. This is referred to as double-loop learning. When viewed in the context of the organization seeking competitive advantage through better use of internal resources it can be seen that this double-loop learning is exactly what needs to be encouraged.

Organizational learning therefore seeks to describe a process of increasing the overall performance of an organization by encouraging knowledge creation and use in each of its value chain functions, in order to render each a source of competitive advantage or core competence. It seeks to do this by arriving at a wider view of each area, such that it can question the existing paradigms that underpin current operation and seek better solutions to the everyday problems.

Learning and knowledge: is there a difference?

In an interview, Peter Senge was asked to expand his views on the learning organization. A brief extract of the transcript is provided below:

Question: How do you define learning?

Senge: Learning concerns the enhancement of the capacity to create. Real learning occurs when people are trying to do something that they want to do. Ask yourselves: why do children learn to walk? Why do they learn to talk? Because they want to. They see an older brother walk across the room and they think, ‘Hey, this looks like a good deal’. It is their intrinsic drive to create something new, to do something that they have never done before that leads to new learning. It is always related to doing something.

Question: Is doing enough?

Senge: No. Real learning has two critical dimensions that are embedded in the phrase ‘expand the capacity to create’. Just creating is not enough. Say you strike it rich by winning the lottery. You brought the right card, which leads to extraordinary results. But you have not expanded your capacity to win the lottery. You did not learn anything by the sheer action of buying the ticket.

Question: How is learning different from knowledge?

Senge: It is not. My colleague Fred Kofman at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] says that ‘learning is the enhancement of or increase in knowledge, and knowledge is the capacity for effective action in a domain, where effectiveness is assessed by a community of fellow practitioners’. There has to be some assessment.

Learning or knowledge is different from information. A fundamental misunderstanding that permeates Western society is that learning and knowledge does not need to be related to action. Colloquially, when we use the word ‘learn’ we most often use it to mean ‘taking in information’. We say, ‘I learned all about finical accounting for executives. I took the course yesterday’. In Japan, they say that you learn when you know it in your body – literally. The Japanese say you do not say, ‘I know it’ because you heard it, but because you know it is in you. This is an important distinction. There is not knowledge until it is in your body, not just in your head. You may not necessarily understand the principles of gyroscopic motion that make riding possible, but you know it within you when you know how to ride a bicycle.

Therefore, learning or knowledge has a cognitive or intellectual dimension, both of which are intricately intertwined and assessed relative to the needs for action. This goes back to John Dewey (1933), who said: ‘All learning is a continuous process of discovering insights, inventing new possibilities for action, producing the actions and observing the consequences leading to insights.’

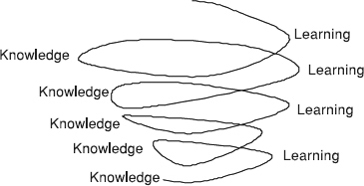

In our view learning involves the action(s) of using existing insight or knowledge to produce new insight or knowledge. Knowledge is a state of understanding (explicit and tacit) which helps guide the form and shape of action(s). Learning and knowledge therefore mutually reinforce each other in a cycle. The act of learning provides knowledge and understanding, which in turn feed further learning. Working in concert, the two create a virtuous spiral of knowledge learning (see Figure 1.2).

Approaches to organizational learning

Ever since Agryris and Schon (1978), raised the question ‘ what is an Organisation, that it learn’, there has been a widespread pursuit of learning as a strategy. Since that exploratory question, many attempts have been made to define and categorize learning, and to explore the various dimensions of learning. One answer was provided by the physicist turned manager, Reg Revans who proposed a formula for action learning:

Fig. 1.2 The knowledge-learning spiral

Learning = P + Q

where

P= programmed learning that comes from books, lectures or secondary sources

Q= learning that comes from asking questions, looking at the evidence, and discussing or drawing conclusions based on experience.

Action learning according to Revans ‘builds primarily on Q’. His basic idea was to organize teams so that every team had two jobs: one is to solve a problem or to complete a project, the other is to learn from the job. Afterwards the learning is to be written down, shared and submitted to the planning group or chief executive officer (CEO) (Revans, 1983).

Another strand in the evolution of the learning organization emerges in the work of Arie de Geus. De Geus, while working for Royal Dutch Shell, was struck by the fact that the average life expectancy of most companies was less than forty years. Yet, some firms were alive and vigorous after more than 200 years. De Geus put forward that most corporations die prematurely – from learning disabilities. They are somehow unable to adapt and evolve as the world around them changes. From the Shell team studies, De Geus identified four common traits in successful corporate citizens:

- a sensitivity to their environments (and potential changes within) which represented their ability to learn.

- a strong degree of cohesion and identity. (Culture, which is considered to be an essential aspect of a company's ability to build a community and persona for itself, and values are often the foundation of this characteristic.)

- tolerance for new or different ways of thinking and acting (often associated with decentralization), which provides an openness for learning and creates a willingness to look objectively at the total ecology of the organization.

- conservative financing (a sensible planned approach toward investments).

Slocum, McGill and Lei (1994) note that leading companies deploy learning strategies for market dominance. These companies adopt three management practices (summarized in Table 1.1) that capitalize on the company's capabilities and culture as well as its competitive strengths:

1 Develop a strategic intent to learn.

2 A commitment to continuous experimentation.

3 An ability to learn from successes and failures.

A manager's greatest challenge is to hone these practices and drive them relentlessly through the organization. These practices (listed below) are a stark contrast to strategies that have worked so well in the past.

Table 1.1 Pillars of learning strategy

In the past |

Pillars |

Learning orientated strategy |

Known capability |

Strategic intent to learn |

Any skill Any capability |

Known market |

Commitment to experimentation |

Any product Any market |

Known result |

Learning from past successes and failures |

Any process of unlearning Any problem-solving process |

Source: Slocum, McGill and Lei (1994)

These practices enable a firm to constantly renew itself and develop new sources of competitive advantage. This contrast between the traditional firm and learning firm is elaborated in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Differences in approach between traditional and learning firms

Strategic dimensions |

Traditional |

Learning |

Underlying premise |

Fit the firm to the environment |

Change the environment to fit the form |

Dominant paradigm |

Mass, size, chess-like |

Manoeuvrability |

Guiding objective |

Preserve advantage |

Renew advantage |

Competitive/analysis |

Generic strategies to lock in local markets |

Create new markets |

Resources/means |

Invested in fixed assets |

Invest in evolving/emerging opportunities |

Problem solving logic |

Formal planning; quantitative analysis |

Intuitive, sense making |

Basis of thinking |

Linear, incremental |

Breakthrough, quantum |

Organizational design |

SBU-based, hierarchial boundaries |

Skill-based, boundaryless |

Roles of alliances |

Cost reduction |

Learning new insights from partners |

Role of customers |

Conceived as marketing tools |

Conceived as groups, individuals to learn from |

Source: Slocum, McGill and Lei (1994)

Knowledge management strategies

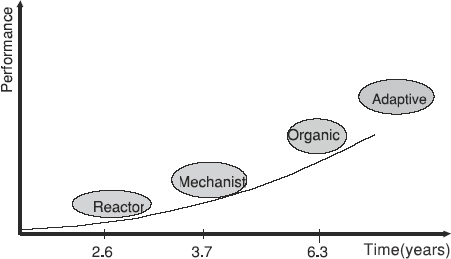

Companies in their attempts to implant knowledge management into their organizations can follow many possible routes. Ahmed (2001) examining performance outcomes of companies following knowledge programmes suggests that there exist three main generic strategies and one emerging generic strategy. The main strategies are: reactive, mechanistic and organic. The emergent form is the adaptive knowledge management strategy. The characteristic associated with of each of these knowledge management strategies are:

1 Reactive knowledge management (or reactors)

(a) ad hoc programme (implicit)

(b) piecemeal implementation

(c) narrow departmental/group focus

(d) lacking senior management support

(e) driven by small group of middle management

(f) poorly understood benefits by individual employee

(g) poor communications and awareness

(h) group/department scale involvement

(i) IT-driven (data-transfer led)

(j) rigid functional structures

(k) benefits purely understood in technical gains (efficiency)

(l) little alignment with long-term strategies.

2 Mechanistic knowledge management

(a) systematic programme (explicit)

(b) organization-wide implementation

(c) mandated by senior management

(d) driven by middle management

(e) organization-wide awareness

(f) organization-wide involvement

(g) good awareness of potential gains for the individual

(h) IT driven (but processes and systems led)

(i) managed structures and processes

(j) benefits broadly understood (efficiency and effectiveness).

3 Organic knowledge management

(a) systematic programme (explicit)

(b) organization-wide implementation

(c) mandated by senior management

(d) driven by middle management

(e) organization-wide awareness

(f) organization-wide involvement

(g) good awareness of potential gains for the individual

(h) people-driven (but backed by IT) processes and systems

(i) benefits broadly understood (efficiency and effectiveness)

(j) open and evolving structures/processes

(k) alignment with strategy.

On examining these summary characteristics, the differences between the reactive and organic approach appears to be relatively clear. The reactive knowledge management approach is characterized by an overall narrow technical and efficiency led focus. It is also a group whose knowledge strategy can be stated to be atypically reactive to outside forces. The defining difference between the mechanistic and organic approaches appears to be much more subtle. The key detectable difference is that organic knowledge management tends to be people driven, placing heavy emphasis of such things as communities of practice and support systems, like rewards and incentives to induce sharing. The mechanistic approach on the other hand, although it possesses many of the characteristics of the organic approach is driven by a much stronger emphasis on IT, and as a whole the approach is top-down driven and heavily prescriptive and structured in outlook. The emerging adaptive format is rare, and appears to encompass organic features with the addition that it contains vastly more open structures and permeable boundaries in its operations and activities. These features lend themselves to endowing a greater internal openness for experimentation, leading to enhanced adaptability.

Stages in knowledge management evolution

Mapping performance against average length of time that a knowledge management programme has been followed produces a very interesting trajectory (see Figure 1.3). Figure 1.3 shows, very clearly, that there appears to be an evolutionary trajectory in knowledge management strategies. It can be tentatively suggested that companies embark upon knowledge management typically within a small part of the organization. These first initiatives are likely to be in reaction to some external attenuating circumstance and are likely to be driven primarily by IT-led initiatives. If successful, these programmes are rolled out organization-wide. Companies that do not succeed are likely to drop the programme, hence the low average life period of the reactive group. The roll-out is accompanied by a wider corporate recognition and buy-in.

Fig. 1.3 Stages in knowledge management evolution

The task of managing large-scale programmes brings with it the need for formal structures of management. In keeping with its IT origin, most of these structures and processes are driven through the management of IT. This is the mechanistic stage of knowledge management.

Over time, the knowledge management programme becomes increasingly embedded within the cultural fabric of the company. At this stage, the practices become more open rather than structured and mechanically driven. This organic stage becomes a stepping-stone to higher-level possibilities of organizational learning and competitive advantage.

In the future, companies will have to be highly geared towards generating innovative solutions to current problems, and will have to anticipate the environmental flux. The higher sensitivity towards utilizing and leveraging knowledge assets enables high-level adaptability. This is the adaptive stage of evolution. Even further into the future, companies will begin to build higher levels of precognition and perception. This will result in the evolution to new platforms of organizational management.

Conclusion

The objective of organizational learning and knowledge management is to create a motivated and energized work environment that supports the continuous creation, collection, use and reuse of both personal and organization knowledge in the pursuit of business success. Central to this equation are two fundamental assets: people (whose knowledge resides in skill, expertise experience, intuition, etc.) and organizations (whose knowledge is embedded within its culture, processes and systems). How well these assets can be capitalized on defines the extent of competitive advantage that may be built. The process of acquiring and using such assets (which are often referred to as generative assets) is what we have come to refer to as knowledge management. Perhaps of even greater significance is the emergence of the belief that generative assets can and must be nurtured and managed. In simple words, it is the duty and function of management to manage knowledge.

The dynamics of the modern marketplace provide a premium to those that are able to utilize their intellectual assets effectively and efficiently. These companies will be the survivors of tomorrow. The question to ask then is – what and how can one develop effective knowledge management and learning systems? Is success derived from technology, from process systems, from employees, from leadership? The simple answer is, from all. Managing knowledge and learning is very much a holistic challenge. It is as much a challenge of managing the parts as it is of managing the whole, simultaneously and seamlessly.