3

Culture for knowledge sharing and

transfer

Many people and companies talk about knowledge management and learning, and the importance of ‘managing’ knowledge. Many actually try to ‘do it’, yet only a few actually succeed. The unfortunate reality is that knowledge for the most part frightens organizations as it is inevitably linked to risk. Many companies merely pay lip service to the power and benefits of learning and knowledge. To a large extent most remain averse to the aggressive investment and commitment that managing knowledge demands. Even though knowledge is debated in senior-level meetings as being the lifeblood of the company, and occasional resources and funds are pumped in, the commitment often dies there. Becoming a true-to-life learning and knowledge-led organization demands more than debate and resources; it requires an organizational culture that constantly guides organizational members to strive for knowledge, and a climate that is conducive to it.

The knowledge imagery

Knowledge is holistic in nature. It covers the entire range of activities necessary to provide value to customers and a satisfactory return to the business. Knowledge is something that cannot be smelt, touched, heard, tasted or seen, yet its outcomes impact on organizational success and survival. Knowledge management is embedded in the organizational environment – it is an almost spiritual force that exists in a company and drives value creation. In this sense, knowledge management is probably best described as a pervasive attitude that allows businesses to see beyond the present and to create the future.

In short, knowledge is the engine of change. Resisting change is a dangerous act in today's fiercely competitive scene – companies cannot protect themselves from change regardless of their excellence or the vastness of their current resource basin. Nonetheless, while change brings with it uncertainty and risk, change also creates opportunity. One key driver of the organization's capacity for change is its ability to manage knowledge. Simply deciding that the organization has to be able to manage knowledge, however, is not sufficient. That decision must be backed by actions that create an environment in which people are so comfortable with knowledge sharing and transfer that they will it spontaneously.

Culture is a primary determinant of knowledge management. Culture has multiple elements that can serve to enhance or inhibit the tendency to share knowledge. A word of caution, however – a culture of knowledge sharing needs to be matched to organizational legacy, competence base and environment. Therefore, to examine culture in isolation is a mistake and to identify one type of culture and propose it as the panacea to an organization's lack of knowledge is to compound that mistake.

When visiting companies that excel in knowledge management, one is left with a certain distinct feeling of extraordinariness. This ‘feeling’ even though it defies definition and despite its intangibility contains organizational ‘concreteness’ as real as heavy tools sitting on the shop floor. This feeling is an expression of the prevailing psyche of each organization. The feel of the organization reflects both its climate and culture.

Knowledge cultures versus knowledge climates

The term ‘climate’ historically originates from organizational theorists such as Lewin (leadership styles create social climates) and McGregor (theory X and theory Y), who used the term to refer to social climate and organizational climate respectively. The climate of the organization is inferred by its members through the organization's practices, procedures and rewards systems, and is indicative of the way the business runs itself on a routine basis. In one sense it is the encapsulation of the organization's real priorities and actions.

All people are observers of the environment in which they live. They shape the environment and are shaped by the environment in which they exist. In interacting with their environment, employees are able to infer organizational priorities. From this understanding they align themselves to achieve their own particular ends. Sometimes these personal ends coincide with those of the organization and sometimes they conflict. Understanding and perceptions therefore act as guiding mechanisms. The practices and procedures that come to define these perceptions are often labelled ‘climate’. Schneider, Brief and Guzzo (1996) define four dimensions of climate:

1 Nature of interpersonal relationships

(a) Is there trust or mistrust?

(b) Are relationships reciprocal and based on collaboration, or are they competitive?

(c) Does the organization socialize newcomers and support them to perform, or does it allow them to achieve and assimilate simply by independent effort?

(d) Do individuals feel valued by the company?

2 Nature of hierarchy

(a) Are decisions made centrally or through consensus and participation?

(b) Is there a spirit of teamwork or is work more or less individualistic?

(c) Are there any special privileges accorded to certain individuals, such as management staff?

3 Nature of work

(a) Is work challenging or boring?

(b) Are jobs tightly defined and produce routines or do they provide flexibility?

(c) Are sufficient resources provided to undertake the tasks for which individuals are given responsibility?

4 Focus of support and rewards

(a) What aspects of performance are appraised and rewarded?

(b) What projects and actions/behaviours get supported?

(c) Is getting the work done (quantity) or getting the work right (quality) rewarded?

(d) On what basis are people hired?

The parameters listed above help to define climate. From these sources, employees draw their inferences about the organizational environment in which they work and understand the priorities accorded to certain goals that the organization espouses.

Closely allied to the concept of climate is culture. Organizational culture refers to deeply held beliefs and values. Culture is therefore, in a sense, a reflection of climate, but operates at a deeper level. Whereas climate is observable in the practices and policies of the organization, the beliefs and values of culture are not visible at that level but exist as cognitive schema which governs behaviour and actions to given environmental stimuli. To illustrate, 3M has the practice of setting aside a certain amount of time for employees to do creative work on their own initiative. To support this, specific seed funding is provided, and the individuals are encouraged to share and involve and become involved in each other's projects. These practices and support (climate) make individuals believe that senior management values knowledge (culture). Culture thus appears to stem from the interpretations that employees give to their experience of organizational reality (why things are the way they are and the how and why of organizational priorities).

If the notion of knowledge culture is to be useful it is important to be clear about what we mean by the term. Failure to specify terms often leads to confusion and misunderstanding. The question, ‘what is knowledge culture?’ is pertinent yet complex. The reason for this is partly to do with the way the concept has evolved and partly to do with the inherent complexity within the concept itself. It is perhaps important to remember that the concept of corporate culture has developed from anthropological attempts to understand whole societies. The term over time came to be used for other social groupings, ranging from whole nations, corporations, departments and even teams within businesses.

There is a multitude of definitions of culture but most suggest culture is the pattern of arrangement or behaviour adopted by a group (society, corporation or team) as the accepted way of solving problems. As such, culture includes all the institutionalized ways and the implicit beliefs, norms, values and premises which underline and govern behaviour. Furthermore culture can be thought of as having two components – explicit or implicit.

- Explicit culture represents the typical patterns of behaviour by the people and the distinctive artefacts that they produce and live within.

- The implicit component of culture refers to values, beliefs, norms and premises which underline and determine, the observed patterns of behaviour (i.e. those expressed within explicit culture).

The distinction is important because it serves to highlight that it is easier to manipulate explicit aspects when trying to fashion organizational change. For example, in trying to make the company knowledge orientated, it may be possible to elicit certain actions and behaviours from employees through relatively simple training in intranet tools and techniques but not necessarily effect any change in implicit culture. A change in implicit culture would necessitate altering the value set of the individual members to the extent that sharing becomes an unconscious norm of action, rather than guided by procedural or other organizational control routines. The degree and extent to which this happens is dependent on the strength of the culture.

The strength of culture relies primarily on two things:

- the pervasiveness of the norms beliefs and behaviours in the explicit culture (the proportion of members holding strongly to specific beliefs and standards of behaviours)

- the match between the implicit and explicit aspects of culture.

Another way of looking at culture is in terms of cultural norms. Creating culture through use of words is seldom enough. O'Reilly (1989) suggests norms vary along two dimensions:

- intensity – the amount of approval/disapproval attached to an expectation

- crystallization – the prevalence with which the norm is shared.

For instance, when analysing an organization's culture it may be that certain values are held widely but with no intensity, i.e. everyone may understand what top management wants but there is no strong approval/disapproval if demands are followed or not. Additionally, it may be that a given norm such as knowledge sharing is positively valued in one group (e.g. marketing) and negatively valued by another (e.g. manufacturing). In this case, there is intensity but no crystallization. Existence of both intensity and consensus creates strong cultures. This is why it is diffi-cult to develop or change culture.

Strong cultures score highly on both intensity and crystallization attributes. Moreover, really strong cultures work at the implicit level and exert a greater degree of control over people's behaviour and beliefs. Strong cultures can be beneficial as well as harmful depending on the circumstances that the organization finds itself. Strong cultures, by virtue of deeply held assumptions and beliefs, help the organization to facilitate behaviours in accordance with organizational principles. A company that can create a strong culture has employees who believe in its products, customers, systems and processes. By subscribing to its philosophy the organization becomes part of the employees’ own identity.

Organizations need also to be wary of strong cultures since it can in some circumstances be a hindrance. To use culture over the long-term, organizations need to posses certain values and assumptions about accepting change. These assumptions and values must be driven by the strategic direction in which the company is moving. Without this dynamic, a strong culture can act as a straitjacket and constrain the need for change. Supporting this apparently contradictory facet of culture, longitudinal studies of culture have found evidence that suggests incoherent and weak cultures at one point in time were associated with greater organizational effectiveness in the future, and that some strong cultures eventually led to decline in corporate performance (Denison and Mishra, 1995). Clearly balance and understanding of context is important.

Generally, we can say that because culture can directly effect behaviour it can help a company to prosper. A sharing culture can make it easy for senior management to implement knowledge strategies and plans. The key benefit is that culture often can do things that simple use of formal systems, procedures or authority cannot. Moreover, given the nature of culture and climate, it is clear that senior managers play a critical role in shaping culture, since they are able to give priority to knowledge sharing, as well as take steps, in terms of rewards for instance, to guard against complacency. Employees take the priorities set by what management values, and use these to guide their actions. The challenge for management, then, is to make sure that the employees make the right type of attributions, since any mismatches or miscommunication quite easily leads to confusion and chaos.

Organizational culture and effectiveness

Apart from defining culture, it is necessary to check the attributes that make for its effectiveness. The topic of culture and effectiveness is of central importance yet the area is beset by formidable problems. Any theory of cultural effectiveness must by definition encompass a broad range of phenomena extending from core assumptions to visible artefacts, and from social structures to individual meaning. In addition, the theory must also address culture as symbolic representations of past attempts at adaptation and survival, as well as a set of limiting or enabling conditions for future adaptation. Indeed, a great deal of scepticism exists about whether culture can ever be ‘measured’ in a way that allows one organization to be compared with another.

Research on organizational culture is easily traced back to classical organization theorists such as Likert (1961), Burns and Stalker (1961) or Lawrence and Lorsch (1967). More recently writers such as Peters and Waterman (1982) have popularized it by espousing a theory of excellence, which purports to identify cultural characteristics of successful companies.

Numerous studies have produced evidence which highlights the importance of culture to organizational performance and effectiveness. To cite a handful of exemplary studies: Kotter and Heskett (1992) present an analysis of the relationship between strong cultures, adaptive cultures and effectiveness; Deshpande, Farley and Webster (1993) link culture types to innovativeness; more generally, Dennison and Mishra (1995) identify four cultural traits and values that are positively related to effectiveness. These are:

1 Involvement. Involvement of a large number of participants appears to be linked with effectiveness by virtue of providing a collective definition of behaviours, systems and meanings in a way that calls for individual conformity. Typically this involvement is gained through integration around a small number of key values. This characteristic is popularly recognized as a strong culture. Involvement and participation create a sense of ownership and responsibility. Out of this ownership grows a greater commitment to the organization and a growing capacity to operate under conditions of ambiguity.

2 Consistency. Consistency has both positive and negative organizational consequences. The positive influence of consistency is that it provides integration and co-ordination. The negative aspect is that highly consistent cultures are often the most resistant to change and adaptation. This concept of consistency allows us to explain the existence of subcultures within an organization. Sources of integration range from a limited set of rules about when and how to agree and disagree, to a unitary culture with high conformity and little or no dissent. Nonetheless in each case the degree of consistency of the system is a salient trait of the organization's culture.

3 Adaptability, or the capacity for internal change in response to external conditions. Effective organizations must develop norms and beliefs that support their capacity to receive and interpret signals from its environment and translate them into cognitive, behavioural and structural changes. When consistency becomes detached from the external environment, firms will often develop into insular bureaucracies, and are unlikely to be adaptable.

4 Sense of mission or long-term vision. This contrasts sharply with the adaptability notion, in that it emphasises the stability of an organization's central purpose and de-emphasizes its capacity for situational adaptability and change. A mission appears to provide two major influences on the organizations functioning. First a mission provides purpose and meaning, and a host of non-economic reasons why the organization's work is important. Second, a sense of mission defines the appropriate course of action for the organization and its members. Both these factors reflect and amplify the key values of the organization.

Denison and Mishra propose that for effectiveness, organizations need to reconcile all four of these traits. The four traits together serve to acknowledge two contrasts:

- the contrast between internal integration and external adaptation

- the contrast between change and stability.

Involvement and consistency have as their focus the dynamics of internal integration, while mission and adaptability address the dynamics of external adaptation. This focus is consistent with Schein's (1985) observation that culture is developed as an organization learns to cope with the dual problems of external adaptation and internal integration. In addition, involvement and adaptability describe traits related to an organization's capacity to change, while the consistency and mission contribute to the organization's capacity to remain stable and predictable over time.

The individual and knowledge culture

Personality traits for knowledge management and learning

Individuals play a fundamental role in organizational culture. Organizations need to consider the type of employees that can most effectively drive knowledge management. From a diverse range of research (psychology to management) it is possible to tentatively postulate a core of reasonably stable personality traits by proximally defining characteristics associated with creative individuals. A select few of these are as follows:

- high valuation of aesthetic qualities in experience

- broad interests

- attraction to complexity

- high energy

- independence of judgement

- intuition

- self-confidence

- ability to accommodate opposites

- firm sense of self as creative

- persistence

- curiosity

- energy

- intellectual honesty

- internal locus of control (reflective/introspective).

There appears to be general agreement that personality is related to creativity and learning orientation. Nevertheless, any attempt to try and use this type of inventory approach in an organizational setting as predictor of learning and sharing accomplishments is fraught with dangers. This is hardly likely to prove any more useful than attempts at picking good leaders through the use of early trait theory approaches. It does, however, highlight the need to focus on individual actors – to try and nurture such characteristics or at least bring them out, if necessary, in an organizational setting.

Personal motivational factors affecting knowledge sharing

At the individual level, numerous motivation-related factors can be suggested as drivers of learning, sharing and creative production. The three key factors are presented below:

1 Intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation (such as inherent personalities described previously in the chapter) is a key driver of knowledge creation and sharing. Extrinsic interventions such as rewards and evaluations may even adversely affect the knowledge creation and sharing motivation because they appear to redirect attention from ‘experimenting’ to following rules or technicalities of performing a specific task. Furthermore, apprehension about evaluation can divert attention away from the knowledge because individuals become reluctant to share or take risks in an environment where individual performance or failure may be negatively evaluated. In contrast, a sharing and learning environment allows individuals to be creative, allows freedom to take risks, play with ideas and expand the range of considerations from which new innovative solutions may emerge.

2 Challenges faced. Open-ended, non-structured tasks engender higher learning and creativity than narrow jobs. This occurs by virtue of the fact that people respond positively when they are challenged and provided with sufficient scope to generate novel solutions. This suggests that it is not the individual who lacks sharing tendency potential but it is the organizational expectations that exert a primary debilitating effect upon the individual's inclination to share and transfer knowledge.

3 Skills and knowledge. Knowledge creation and exploitation is affected by relevant skills such as expertise, technical skills, talent, etc. However, domain-related skills can have both positive as well as negative consequences. Positively in-depth knowledge enhances the possibility of creating new understanding. Negatively high-domain relevant skills narrow the search heuristics to learnt routines within functional departments. This fundamentally constrains new perspectives and leads to functional ‘fixedness’ and a functional ‘blindness’.

Yet another challenge facing organizations is that at a more macro level organizations may attract and select persons with matching styles. Organizational culture, as well as other aspects of the organization may be difficult to change because people who are attracted to the organization may be resistant to accepting new cognitive styles. When a change is forced, those persons attracted by the old organization may leave because they no longer match the newly accepted cognitive style. Among other things, this culture-cognitive style match suggests that organizational conditions (including training programmes) supportive of a knowledge culture will be effective only to the extent that the potential and current organizational members know of and prefer these conditions.

Structure and knowledge sharing

Although most research appears to agree that knowledge is influenced by social processes, research in this area thus far has taken a back seat to research on individual differences and antecedents. Generally it can be said that knowledge is enhanced by organic structures rather than by mechanistic structures. Knowledge sharing is increased by the use of highly participative structures and cultures (e.g. high performance–high commitment work systems). For instance, a knowledge champion must be made to feel part of the programme – involvement via ownership enhances attachment and commitment at the organizational level.

Organic structures promote knowledge sharing:

- freedom from rules

- participative and informal

- many views aired and considered

- face-to-face communication; little red tape

- interdisciplinary teams; breaking down departmental barriers

- emphasis on creative interaction and aims

- outward looking; willingness to take on external ideas

- flexibility with respect to changing needs

- non-hierarchical

- information flows downwards as well as upwards.

Mechanistic structures hinder knowledge sharing and transfer:

- rigid departmental separation and functional specialization

- hierarchical

- bureaucratic

- many rules and set procedures

- formal reporting

- long decision chains and slow decision making

- little individual freedom of action

- communication via the written word

- much information flows upwards; directives flow downwards.

Cultural norms for knowledge sharing and transfer

Bearing in mind, external context impacts heavily upon organizational efforts to manage knowledge we need to ask how culture can promote knowledge sharing and transfer? Indeed, does culture hinder or enhance the process of knowledge sharing and transfer? The answer is that it simply depends on the norms that are widely held by the organization. If the right types of norms are held and are widely shared, culture can activate knowledge sharing. Just as easily, if the wrong cultural norms exist, regardless of the effort and good intention of individuals trying to promote knowledge, little knowledge transfer is likely to be forthcoming as a result.

Investigation into this by examining case examples as well as empirical work suggests a common set of critical norms involved in promoting and implementing knowledge, learning and creativity.

Norms that promote knowledge sharing and learning are summarized below.

1 Challenge and belief in action – the degree to which employees are involved in daily operations and the degree of ‘stretch’ required. Key attributes:

(a) do not be obsessed with precision

(b) emphasis on results

(c) meet your commitments

(d) anxiety about timeliness

(e) value getting things done

(f) hard work is expected and appreciated

(g) eagerness to get things done

(h) cut through bureaucracy.

2 Freedom and risk-taking – the degree to which the individuals are given latitude in defining and executing their own work. Key attributes:

(a) freedom to experiment

(b) challenge the status quo

(c) expectation that knowledge is part of your job

(d) freedom to try things and fail

(e) acceptance of mistakes

(f) allow discussion of dumb ideas

(g) no punishment for mistakes.

3 Dynamism and future orientation – the degree to which the organization is active and forward looking. Pace of work is ‘full speed’, ‘breakneck’, etc. Key attributes:

(a) forget the past

(b) willingness not to focus on the short term

(c) drive to improve

(d) positive attitudes towards change

(e) positive attitudes toward the environment

(f) empower people

(g) emphasis on quality.

4 External orientation – the degree to which the organization is sensitive to customers and external environment. Key attributes:

(a) adopt customers perspective

(b) build relationships with all external interfaces (e.g. suppliers, distributors).

5 Trust and openness – the degree of emotional safety that employees experience in their working relationships. When there is high trust new ideas surface and sharing of these occurs more easily (see TOTS model in this chapter). Key attributes:

(a) open communication and share communication

(b) listen better

(c) open access

(d) accept criticism

(e) encourage lateral thinking

(f) intellectual honesty.

6 Debate and listening – the degree to which employees feel free to debate issues actively, and the degree to which minority views are expressed readily and listened to with an open mind. Key attributes:

(a) expect and accept conflict

(b) accept criticism

(c) do not be too sensitive

(d) opened-mind listening.

7 Cross-functional interaction and freedom – the degree to which interaction across functions is facilitated and encouraged. Key attributes:

(a) move people around

(b) teamwork

(c) manage interdependencies

(d) flexibility in jobs, budgets, functional areas

(e) cross-functional process orientation.

8 Myths and stories – the degree to which success stories are designed and celebrated. Key attributes:

(a) symbolism and action

(b) build and disseminate stories and myths.

9 Leadership commitment and involvement – the extent to which leadership exhibits real commitment and leads by example and actions rather than just empty exhortation. Key attributes:

(a) senior management commitment

(b) walk the talk

(c) declaration in mission/vision.

10 Awards and rewards – the manner in which successes (and failures) are celebrated and rewarded. Key attributes:

(a) ideas are valued

(b) top management attention and support

(c) respect for beginning ideas

(d) celebration of accomplishments, e.g. awards

(e) suggestions are implemented

(f) encouragement.

11 Time and training – the amount of time and training employees are given to develop and share new ideas and new possibilities, and the way in which new ideas are received and treated. Key attributes:

(a) built-in resource slack

(b) funds budgets

(c) time

(d) opportunities

(e) promotions

(f) tools

(g) infrastructure, e.g. rooms, equipment, etc.

(h) continuous training

(i) encouragement of lateral thinking

(j) encouragement of skills development.

12 Corporate identification and unit – the extent to which employees identify with the company, its philosophy, its products and customers. Key attributes:

(a) sense of pride

(b) willingness to share the credit

(c) sense of ownership

(d) absence/elimination of mixed messages

(e) shared vision and common direction

(f) build consensus

(g) mutual respect and trust

(h) concern for the whole organization.

13 Organizational structure: autonomy and flexibility – the degree to which the structure facilitates knowledge activities. Key attributes:

(a) decision-making responsibility at lower levels

(b) decentralized procedures

(c) freedom to act

(d) expectation of action

(e) belief the individual can have an impact

(f) delegation

(g) quick, flexible decision making

(h) minimum bureaucracy.

Culture change

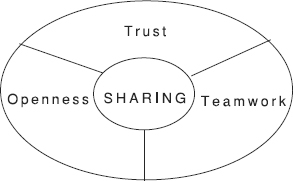

As knowledge rests largely in people's heads, managing it requires aligning employees’ goals against those of the organization (Michele, 1996). Ensuring that both the workers and the organization share similar goals saves a lot of future effort in sorting out office politics, bargaining with the individual or even dealing with the unions. Alignment requires the instalment of appropriate infrastructures that have to be in place to support the capturing, sharing and using of knowledge. These infrastructures are linked to basic human feelings which organizations should learn to adopt and manage. As knowledge management is essentially about sharing one's knowledge, one has to be comfortable about sharing. It is through trust, openness and team-work that the basic foundation for sharing is formed. People, who trust one another, will share information and are more likely to listen to one another in a team situation (Sonnenberg, 1994).

Trust refers to one's perception of integrity, reliability and openness, be it in an individual to group environment or within a group (Sonnenberg, 1994). The literature is unequivocal in its views that trust features centrally in a host of organizational desired outcomes. Golembiewski and McConkie (1975) state that trust determines the effectiveness of relationships within groups. A high level of trust among people is linked to increased profits and improved customer loyalty (Sonnenberg, 1994). Schindler and Thomas (1993) note that trust improves productivity in teamwork. The ties between trust, openness and team-work for sharing (TOTS) to occur constitute the TOTS model in Figure 3.1.

The TOTS model

1 Trust does not only apply to managers trusting employees to act in the organization's best interest, but also to managers themselves to act in ways that earn trust from their workforce. Also, as the business grows, so does the responsibility of the staff and hence a certain degree of freedom to practise their own initiatives must be given. Regardless of whether the driving force for change is in eliminating waste, improving quality of service or product, workers at all levels need to be empowered to act in their personal capacity to make effective decisions be it in a group or as individuals. Empowerment requires management's trust in employees.

2 Openness. Building on some existing level of trust, openness makes employees feel more comfortable in confiding in people knowing that their trust will never be broken. This establishes an open line of communication between all levels of the organization and further encourages the sharing of knowledge. Trust coupled with appropriate rewards prompts employees to further contribute to the organization's knowledge repository.

3 Teamwork. Managers can achieve trust by acting as part of a team. It is necessary under team conditions to offer help only when asked, and not be seen as a person who just gives the orders and imposes the rules. Combined with openness and trust, teamwork creates a formidable weapon, which cannot easily be copied by competitors. Such communities of interest might already exist informally, but they need to be formally recognized for sharing to become part of the corporate culture. Hence using existing teams or workgroups would be a good starting point.

Fig. 3.1 The TOTS model

Sharing: the desired result of creating an environment of trust, openness and teamwork.

Why is sharing difficult?

Sharing is by no means an easy task. Ask any child to share his or her favourite toy with you! The same is true for most of us in organizations. It is interesting then to note that the problem is probably even more acute given that most of us have gone through an education system and social indoctrination that frowned upon teamwork, emphasizing instead the need to be competitive, independent and self-reliant. This idea of individual efforts and knowledge hoarding is perpetuated in the working environment. Furthermore, hierarchical structures within organizations lead individuals to use knowledge hoarded as a means of advancement and hence the ubiquitous phrase ‘knowledge is power’. This is further demonstrated none more so than on our personal knowledge repositories, the personal computer. Passwords are required, reinforcing the notion that sharing is not encouraged. With locked filing cabinets and information access restrictions, the growth of the organization is severely impeded creating an environment counter to sharing. Hence, strategies have to be in place to promote sharing, and questions have to be asked regarding recruitment criteria, management styles, corporate structures, training, compensation and reward schemes, to help break the mould of ‘selfish’ organizations.

The barriers to knowledge management are reflected in two common employee attitudes:

1 Knowledge is power.’ This attitude gives employees a sense of security and political influence within the organization. Structurally, many organizations exhibit and even encourage such ‘turf’ battles. Dysfunctional internal rivalries are sustained through functional and/or product silos. To seek knowledge from these internal sources is seen as compromising themselves – an admission of ignorance rather than of learning. Consequently, individuals hoard their personal knowledge and refrain from sharing or learning new knowledge.

2 ‘Knowledge sharing is not my job.’ Employees view knowledge management as a job ‘add-on’. They are paid to do their job, not for the time it takes them to do it. This attitude is perpetuated by the inadequacies of existing knowledge systems that often are not user-friendly. Furthermore given the extra effort required and the loss of ‘power’, the way work is structured and rewarded may run counter to nurturing a sharing and learning culture.

Attitudes that hinder knowledge management must be communicated and understood by managers and employees. This helps employees to accept the need for a culture change and its value for the organization and, ultimately, for themselves.

Strategies for sharing

Organizations that support their knowledge management applications with cultural and structural change initiatives are much more likely to receive high returns on investment. These changes should focus not just on removing the cultural barriers but also on creating the proper environment for knowledge sharing and learning to flourish.

The following five factors have been identified as having a positive effect on people's eagerness to share and learn:

- core cultural values

- recruitment of suitable personnel

- role of human networks

- rewards as a motivational tool

- the role of a champion.

Cultural values

Typically, most organizations have a set of corporate values that are explicitly stated and aligned with the business strategy. Given that knowledge management is integral to the business strategy, the new knowledge management behaviours should either be formalized as part of the corporate values or be introduced as a distinct set of knowledge management values.

The crucial knowledge management value that must be articulated and nurtured is that of knowledge sharing, transforming the attitude that ‘knowledge is power’ to that of ‘sharing knowledge is power’.

In addition, other values that will support a sharing and learning culture include:

- Open communication: encouraging dialogue and access between all levels of employees to facilitate real-time exchanges and feedback, thereby creating learning opportunities from both successes and failures by encouraging experimentation, learning by trying, and management having a higher tolerance to mistakes taking them as lessons learnt.

- Networking: establishing a community with a common purpose in which employees assume a broader perspective and engage in exchanges through cross-functional teamworking.

Recruitment of suitable personnel

Hiring people who are good at learning and teaching makes a big difference in the effectiveness of knowledge management. ‘If you've got people who are hungry to learn, and people who are good at transferring knowledge, the organization will be much more alive’ (Davenport, quoted in Wah, 1999). The role of the human resources department has therefore never been more critical as it has to have the vision to employ the right people with the desired traits, either determined through psychometric tests or through a well-developed training programme that is capable of inculcating and maintaining the will to learn and transfer learning. Hence it has to have systems in place to hire appropriate staff as well as training systems and job rotation schemes to ensure knowledge is shared and used as competitively as possible.

Role of human networks

There are probably many potential strategies to facilitate a culture where knowledge is valued and shared efficiently, but one that is highly effective is that of creating formal communities of interest (Kaye and Hogan, 1999).

In a recent survey (Eckhouse, 1999), 72 per cent of IT managers responded that their technical teams have a clear understanding of the value of knowledge management, but estimated that only 43 per cent of senior executives grasp its value. More crucially, only 11 per cent of these IT managers indicated that it is easy or somewhat easy to change their organizations’ culture to encourage knowledge sharing and collaboration.

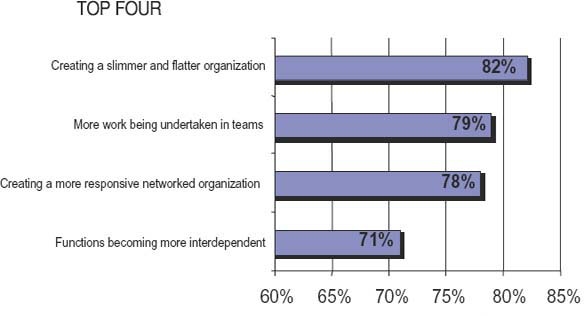

Fig. 3.2 Reasons for restructuring

In another survey of CEOs and senior executives (Skyrme and Amidon, 1997) on how they were restructuring to meet the needs for knowledge management indicates that organizations were becoming flatter and highly networked. The top four responses are shown in Figure 3.2.

Knowledge sharing will only take place if mechanisms exist in the organization to bring people together. Connecting people can be done either through formal or informal mechanisms (Table 3.1). The more there is of such mechanisms, the higher the chances of facilitating more of the right conversations between individuals.

Table 3.1 Mechanisms for creating connections

|

Temporary/flexible |

Permanent |

Formal |

Office layout Multi-function teams Multi-function committees Co-location Secondment, job rotation |

Reward systems Training and development Building design Formal knowledge bases Cross-functional career path Defined co-ordination roles Groupware, intranet (some) Informal networks Professional networks |

Informal |

E-mail, groupware (some) Meeting areas, team rooms Meetings, events Share-fairs Communities of practices |

Source: Skyrme and Amidon (1997)

As a result of business process re-engineering and other change initiatives, many companies have moved to a cross-functional team model as a key building block of the organization. These teams usually comprise individuals from different professions or jobs, whose knowledge and skills are needed to produce a whole output. Cross-functional teams are characterized by common goals, interdependent work and joint accountability for results. Despite their benefits, cross-functional teams can also become the new silos and could experience trouble in getting information from other teams. Being aware of this can certainly help in being part of an effective cross-functional team.

Rewards and motivation

Creating a culture of sharing may be the most difficult obstacle to overcome. Current performance and rewards systems exemplify an individual's personal achievement and rarely takes into account an individual's contribution to or participation in formal collaboration efforts. For sharing to take off, this must change. Reward structures and performance metrics need to be created which benefit those individuals who contribute to and use a shared knowledge base. Based on Herzberg's (1987) theory of individual motivation, which assesses five factors as motivators – challenge of work, promotional opportunities, sense of achievement, recognition of job done and sense of responsibility – those who excel at knowledge sharing should be recognized either in public forums such as newsletters and e-mails or be made to understand that the success and advancement in their career will be based on knowledge management principles. Davenport suggests that, ‘sharing knowledge is mostly considered a sideline activity. Workers will only take it seriously when rewards are built into the compensation and benefits plan’. He goes on to say that ‘the best kind of knowledge transfer is informal, but the best way to get knowledge transferred is to reward them for transferring it’ (Davenport, quoted in Wah, 1999).

The role of a champion

In any new form of management initiative, a leader should be chosen to head the call for reform (Puccinelli, 1998). In organizations they may be referred to as champions. It is, however, critical to select the right champion. Earl and Scott (1999) point out that it is advantageous if the champion were to come from within the organization, as knowing the organization, its culture and its key players, renders acceptability and yields advantages in the consulting and influencing aspects of becoming a champion. Also, having been in the organization and having had a certain length of experience, helps give credibility to the entrepreneurial and building aspects of the job. Some organizations have elected chief knowledge officers (CKO) as their champions, but one of the fundamental requirements for sharing is the lack of any formal hierarchy. A hierarchical title of ‘CKO’ can damage the creation of a successful knowledge-based organization. This would appear to indicate that a CKO should only exist, as a temporary position until the organization becomes self-sufficient and the CKO's championing of sharing has become part of the organizations culture.

A good example of electing a champion is found in Glaxo Wellcome Research and Development, which uses ‘thought leaders’ as knowledge carriers within the organization (Macleod, 1999). Crucially, their roles involve ensuring that knowledge is leveraged into profitable innovations, which is important in a busy environment where knowledge can easily be lost.

Conclusion

The organization's people are central to the deployment of a knowledge management strategy. Because knowledge is rooted in human experience and social context, managing it well means paying attention to people and to individual and organizational culture. As such, the implementation of processes supporting knowledge management can only be carried out successfully if it is accompanied by corresponding changes in both individual and organizational behaviours.

In attempting to build an enduring company, it is vitally important to understand the key role of the ‘soft’ side of the organization in knowledge management. Many companies have failed in their learning and knowledge programmes because they focused narrowly on managing technical aspects of knowledge management and failed to appreciate the importance of culture and climate in innovation. Many companies expend large amounts of energy in turning around their technology-led knowledge programmes or re-energizing them. Instead, their time would have been better spent designing and creating an environment for learning and knowledge sharing. These company leaders need to note that the most successful knowledge management companies have leaders who spend their energy and effort in building organizational cultures and climates which perpetually create learning and innovation through knowledge sharing. Without doubt the most successful companies of the future will be dominated by those that do not simply focus energies upon products and technical innovations, but those who have managed to build enduring environments of human communities striving towards knowledge sharing through the creation of appropriate cultures and climate. This will be the energy of renewal and the drive to a successful future.