5

Measurement and technology

Knowledge, like people, is a resource for companies to harness and from which to obtain returns. However, it is becoming apparent that knowledge, as opposed to traditional resources, is actually subject to increasing returns, thus making it more attractive than before to companies. Hence, building up a knowledge resource would enable companies to leverage on a competitive advantage not easily copied by others. The dawning of the importance of the knowledge resource has long been apparent, especially when evaluating companies for the purpose of trading on the stock market. Examples are plentiful of companies trading several hundred per cent over their actual asset value, all due to their ‘hidden value’.

Even though the measurement of knowledge and intangible assets is a science that cannot be mastered accurately, several methods for measuring have been widely used. Some of the methods are briefly described at the end of this introduction. However, before we move on to these, let us go through some broad fundamentals which originate from the old philosophy of total quality management (TQM) and see how they can be used in this knowledge era.

The PDCA cycle in a knowledge management context

Going back to the total quality movement, theorists such as Deming (1986) have argued that skill acquisition and development will make or break a successful quality strategy. Managing by using Deming's PDCA cycle (Plan–Do–Check–Act) is suggested here, but with a knowledge twist and using it in conjunction with a matrix to make it more complete.

1 Capturing or creating knowledge (Plan). A variety of knowledge repositories offer ways to capture knowledge from external sources (competitive intelligence, vendor comparisons and analyses), structured internal sources (marketing reports, customer profiles) and unstructured internal sources (meeting minutes, lessons learnt).

2 Sharing knowledge (Do). Using electronic and hard copies as communication tools, as well as through informal or formal discussion groups to aid sharing of knowledge.

3 Measuring the effects (Check). Using outcome measures to track the success of the above activities. This will be described in more detail in the analysis of the matrix below.

4 Learning and improving (Act). Hinging on the TQM philosophy of continuous improvement, the above measures will lead the organization towards further efforts to better the ‘scores’.

Knowledge management model

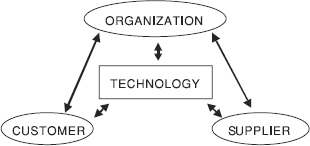

The method of analysing different elements to be measured is proposed here as the COST model, shown in Figure 5.1. In essence there are four perspectives to look at:

1 Customer. What are the known customer problems and solutions? What are the frequently asked questions (FAQs) and what were the answers? What can we learn from our customers? How can we learn from our customers? How can we be more effective in learning from our customers?

Fig. 5.1 The COST model

2 Organization. What are the key skills needed to make the business a success? Who has these skills? How are these skills harnessed, and shared? How are we doing compared with other organizations?

3 Suppliers. How are our supplier links? Does the organization obtain an optimum quality, cost and delivery service from the suppliers? Does the organization conduct supplier quality programmes? How are our links with our joint venture and other business partners?

4 Technology. How many computer terminals (which are hooked up for information transfer) are available per employee? Are these links being used effectively within the customer–organization–supplier value chain? Is technology enabling information to be transferred and made available when and wherever the user is?

The COST model forces practitioners to think about the links between the working functions of an organization. It also puts the technological perspective in its proper place, i.e. it is only an enabler to organize and disseminate information. An example of this link is the use of computers by Federal Express, who allow customers to track their parcels on line anywhere in the world, as it is being transported. This service demonstrates the importance of technology, linking all three core elements of the above model, in order to provide high quality customer satisfaction.

The knowledge management matrix

Combining the COST model and the PDCA – within a knowledge management context, we obtain the matrix in Figure 5.2. This matrix helps in obtaining a deeper understanding of how knowledge management affects the organization as a whole and it also prompts practitioners to look at the various aspects of implementing knowledge management. It forces the practitioner to consider all factors, ‘soft’ as well as ‘hard’, and it also forces managers to link knowledge management to the organization's overall policy and strategy. It will also allow managers to list out the important functions that support knowledge management and to prioritize them. The measures suggested are by no means complete, but we list them as a catalyst for mangers to think of measures which suit their organization's current environment.

Customer matrix

Customer measurements have been suggested which include market share, number of customers and annual sales/customers (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997). These are some measures of intellectual capital that aid in managing knowledge, e.g. if the organization is interested in measuring and capturing its effectiveness in the customer support department. Counter-productive measures are often used during the analysis, e.g. number of completed calls per hour. Though these efficiency measures do have their uses, it encourages throughput rather than satisfied customers. For example, employees are ‘incentivized’ to finish with customers as quickly as possible irrespective of whether customer problems have really been solved or not. This results in a dissatisfied customers. Short-sighted measures create environments where employees will not have the time or interest to add their own experiences, discoveries and solutions to the firm's knowledge repositories.

|

Capture |

Share |

Measuring |

Learning |

Customer |

|

|

|

|

Organization |

|

|

|

|

Supplier |

|

|

|

|

Technology |

|

|

|

|

By moving horizontally across the matrix, managers will be prompted to think of further measures that would indicate the success or failure of knowledge management activities.

Organization matrix

The organizational matrix involves looking at the people as core components of the organization. Professor Hirotaka Takeuchi of the Harvard Business School (speaking at the First Annual University of California Berkeley Forum on ‘Knowledge and the firm’) said, ‘The natural place for knowledge to reside is in the individual. The important question is how to convert individual knowledge to organizational knowledge. The Japanese view is to give people a process to create new knowledge’ (Cohen, 1998) The Japanese have long viewed knowledge to be an integral part of their work, and hence have been using quality circles (QCs) and job rotation as part of their knowledge programme. Measures that could be monitored in this part of the matrix include metrics such as number of workers participating in QCs, number of workers rotated, etc. These can be supplemented by other broader measures. For instance, metrics could be constructed to focus upon obtaining specific types of behaviours and attitudes, which facilitate an environment of trust and collaboration.

Supplier matrix

Suppliers are often mistreated in current working environments. Supplier partnerships have only recently come to light and been acknowledged to be an integral part of the success of an organization. Suppliers’ knowledge is often of vital importance to companies. For example, a supplier's knowledge of raw materials can be passed on to the customer, allowing for a more informed decision to be made. This is evident in the workings of Japanese manufacturing companies, such as Matsushita who often hold meetings with their suppliers to exchange views and to discuss new projects. This is part of the knowledge dialogue that forms the foundation of knowledge management.

Measures which maybe useful include:

- number of supplier meetings

- number of supplier development programmes

- number of benchmarking activities between suppliers.

Technology matrix

This matrix effectively defines the type of system a company needs to obtain in order to improve their management of knowledge. Capture defines the needs of the organization as in how many people will be linked into the system and in what form will the information be stored. Information captured will then have to be shared and this determines the interaction media to be used. As for effectiveness, decisions which were made based on the knowledge transmitted using technology need to be calculated, either in the form of outcomes such as the contribution to the profit levels of the business or in more direct forms such as the number of times the knowledge base was accessed to supplement the decision-making process. Finally, the improvements which can be learnt using technology are those such as, is there an overload of information? Is all of it relevant? How can we ‘police’ the information posted out, in terms of the accuracy of information?

Not all ‘suggested’ knowledge will prove to be useful. It is important, therefore, to ensure that the quality of information held within the knowledge repositories is preserved. One way of addressing this is to use human editors and knowledge quality-checkers to police the knowledge capture process. High-quality knowledge repositories can only be achieved through considerable investment in humans. That is, of course, until technology evolves to give us a ‘thinking computer’.

Hence, it is important that knowledge managers define clearly the requirements for any technology they intend to employ.

Popular knowledge management measurement tools

Many companies are still using traditional accounting tools that were developed in the first half of the twentieth century, and knowledge practitioners are being made to do the impossible – use traditional accounting tools to make the key success factors of the knowledge era visible. Through the years, various measurement systems have been used among the knowledge practitioners. Three commonly used systems are discussed below (Bontis et al., 1999).

Economic value added (EVATM)

Economic value added was introduced by Stern Stewart and Co., a New York based consulting firm, in the late 1980s as a tool to help organizations pursue their prime financial directive by aiding in maximizing wealth of their shareholders. It was an improvement from the traditional financial measures such as return on investments (ROI) and return on equity (ROE) which have been criticized for not guiding strategic decisions.

Economic value added is the difference between net sales and the sum of operating expenses, taxes and capital charges. Expressed in an equation, it is:

Net sales – Operating expenses – Taxes – Capital charges = EVATM

Where capital charges are calculated as the weighted average cost of capital multiplied by the total capital invested. In practice, EVATM increases if the weighted average cost of capital is less than the return on net assets, and vice versa.

By drawing attention on the cost of capital and the drivers of its value, EVATM enables management to focus their actions towards the effective use of their current assets. EVATM added also complements TQM in continuous improvement. Whereas the former concentrates on products and processes, EVATM focuses attention on continuous value creation.

According to Stewart Stern, ‘By assessing a charge for using capital, EVATM makes managers care about managing assets as well as income, and for properly assessing the trade-offs between them. All key management decisions and actions are thus tied to just one measure, EVATM (Skyrme and Amidon, 1998).

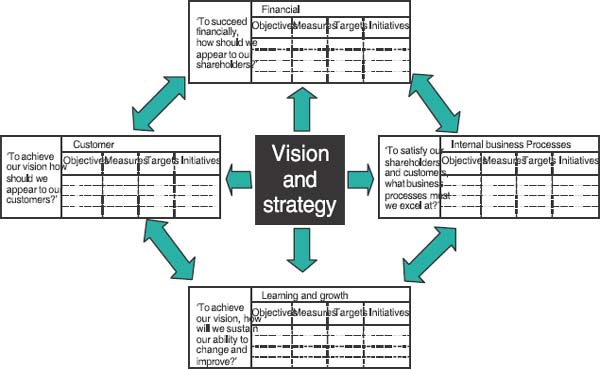

The balanced scorecard (BSC)

One of the methods that has been gaining popularity as a knowledge measurement tool was developed by Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton who first described it in a Harvard Business Review article in 1992. It supplies managers with a multidimensional measurement system that not only caters to financial measures but adds three additional perspectives, namely, a customer perspective, an internal business processes perspective and a learning and growth perspective (Figure 5.3).

1 Financial perspective: includes traditional accounting measures, which address the fundamental question of, are we creating value for all our stakeholders?

2 Customer perspective: measures relating to the performance of the organization's products or services, as well as marketing focused measures such as, how well are we meeting our customer's needs? What are their satisfaction levels? Are our value-added services of value to them?

Fig. 5.3 The balanced scorecard. Source: Kaplan and Norton (1992)

3 Internal business processes: measures are basically drawn on the concept of the supply chain where they are chosen to increase the effectiveness and productivity of manufacturing a product or providing a service that satisfies customers needs.

4 Learning and growth: this perspective allows for the organization to focus on developing knowledge within its individuals that would influence organizational growth. Managing information within the organization to help employees grow is a process often measured by, e.g. number of entries into a knowledge repository and, more traditionally, number of courses attended, bearing in mind the initiatives being measured are deemed to have a direct impact on the organization's overall strategy.

Measuring intellectual capital

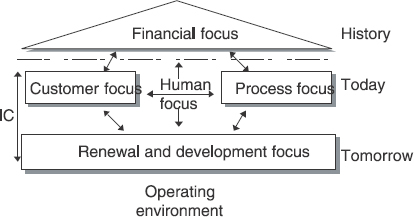

Taking the lead in developing measures of intellectual capital (IC) is the Swedish financial services company Skandia AFS, who supplemented their 1994 annual report with the now legendary Skandia Navigator (Figure 5.4).

Fig. 5.4 The Skandia Navigator. Source: Edvinsson and Malone (1997)

The Navigator has five areas of focus. Aptly focused and directed organizational attention enhances the value of the company's intellectual capital.

The actual layout of the Navigator is like a house. The triangle at the top being the attic, containing the old balance sheet, which still fundamentally acts as the Holy Grail of accounting measures. However, the financial measures are an indication of how the company was at a precise moment in the past and are not forward looking. The term ‘focus’ is supposed to allow for a more futuristic look into how measures of performance and efficiency can lead to improvements.

The ‘walls’ of the house represent the present environment enclosing the company's current activities. These are captured generically by two elements: ‘customer focus’ and ‘process focus’. The first measures a distinct type of external intellectual capital, and the second is a broader measure capturing structural capital. At the bottom is the foundation of the house: the ‘renewal and developmental focus’, which measures how well an organization is preparing for the future. This is assessed through developmental programmes for employees, research and development for products and services, as well as addressing future scenarios of environmental development.

In the centre of the house is the ‘human focus’, which is the heart and soul of the entire organization. This part of the organization leaves every day at 17.00, and one can never be entirely sure of their return. People represent the ‘vitals’ for running any organization. Thus, monitoring the competence and the abilities of the employees, as well as future plans for development, is a key measurable item in this focus area.

The Navigator is used as a model to drive sustained business development and to ensure that management's actions support the renewal and development process as well as financial performance. The Navigator provides Skandia with a nomenclature for intellectual capital reporting. Looking distinctly similar to the balanced scorecard, the Navigator detracts by providing emphasis on the human factor. Table 5.1 shows a sample of actual measures used by Skandia (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997).

Technological aspects

Although technology may not be the complete answer to the difficulties of knowledge management, it can be argued that it helps create the right organizational culture through facilitating proper knowledge capture, storage and dissemination. Many organizations, particularly large multinationals, often do not know of their internal competencies. This situation is aggravated by circumstances where the organization has many business units, organized as profit centres and working independently. Valuable knowledge is held within these ‘silo centres’ but does not get passed around or made use of by the whole organization.

Table 5.1 Sample of actual measures by Skandia

Focus |

Measures |

Financial |

Profits resulting from new business operations ($) Lost business revenues compared to market average (%) Value added/employee ($) Value added/IT employee ($) Investments in IT ($) |

Customer |

Market share (%) Telephone accessibility (%) Customer rating (%) Customer visits to the company (no.) Days spent visiting customer (no.) |

Human |

Leadership index (%) Motivation index (%) Average years of service with the company (no.) Average age of employees (no.) Time in training (days/year) (no.) |

Process |

Administrative expense/total revenue (no.) Cost of administrative errors/management revenue (no.) Contracts filed without errors (no.) Processing times, out payments (no.) IT expense/employee ($) |

Renewal and development |

Competence development expense/employee ($) Marketing expense/customer ($) Share of training hours (%) Average age of company patents (no.) Patents pending (no.) |

Technology plays a pivotal role in enabling knowledge management, since it helps to bridge organizational silos and enhance interaction. We provide below a brief review of some key considerations that need to be taken into account when using technology to manage for knowledge.

Technology for knowing what organizations know

Every day, organizations large and small create billions of bytes of data about all the different aspects of their business, millions of individual facts about their customers, employees and operational details of products or services rendered. For the most part, this data is kept either in individuals’ heads or in computer databases which, as the size of the company increases and its information hoard grows, becomes larger and more difficult to access. Experts have estimated that only a small percentage of data captured is actually made use of again to aid the decision-making process. So, while the technologies for manipulation and presentation of data has improved by leaps and bounds, the source data still sits divided in individual segments and hidden in a dusty database, whether it is a cupboard or state-of-the-art e-repository. There is, therefore, a need to address ‘data warehousing’ so that organizations can use a common pool of relevant information or, alternatively, pool the different sources of existing information and enable a search for relevant information when required.

Data warehousing/creating knowledge repositories

As Ruggles (1998) points out, knowledge repositories capture explicit, codified information wrapped in varying levels of context. Repositories are used to store and make accessible ‘what we know’ as an organization. Repositories include ‘data warehouses’, which are useful in knowledge management when the mining and interpretation of their content allows employees to become better informed. However, current warehouse systems tend to be relatively devoid of context, requiring significant interpretation by users. It is suggested that more sophisticated repository systems are developed since they can enable wrapping more context around information. The best repository attempts to add context to information as it is being captured. For example, simplifying and organizing the documents stored, into common understandable headings, easily searched by everyone in the organization (based on a common context) and not just limited to the authors of the particular document. Additionally, the system should allow users to comment on the vast assemblage of materials (such as text documents, spreadsheets, images and audio recordings) collected within the database. Incorporating these comments and feedback means that each employee is not only able to draw from, but also is able to contribute to a dynamic evolving experience base. Whatever the level of sophistication, repositories essentially capture data, information and knowledge in forms and through processes that enable access throughout the company. Over time, these repositories will contribute to the maintenance of the organization's shared intelligence and organizational memory.

Perhaps the most important concept that has come out of the data warehouse movement is the recognition that there are two fundamentally different types of information systems in all organizations: operational systems and informational systems (Orr, 1996).

Operational systems are, just as their names imply, the systems that help us run the day-to-day operations of the organization. These are the backbone of any organization and, because of their importance to the organization, almost always end up being the first areas to be computerized (e.g. payroll function, inventory control, accounting systems, etc.). Over the years, these operational systems have been overhauled and extremely well integrated into the organization. Indeed, most large organizations would not be able to function without their operational systems.

On the other hand, there are other functions that go on within the organization that have to do with strategic planning, forecasting and managing. These functions are also critical to the organization especially in the current Internet-speed environment. Functions like market planning and inventory management also require information systems to support them. However, these functions are different from operational ones and the types of systems and information required are also different. The knowledge-based functions are information-led systems.

Informational systems are concerned with analysing data and making decisions, often major decisions, about how the organization operates currently and in the future. Hence, not only do informational systems have a different focus from operational ones, they often have a different scope too. Where operational data needs are normally focused upon a single area, informational data needs often span a number of different areas and need large amounts of related operational data.

Using an intranet

Not every intranet project should be considered a knowledgemanagement effort. Intranets are often used to support knowledge access and exchange within organizations. Unlike technologies such as transmission control protocol/Internet protocol (TCP/IP) and linked hypertext web pages, intranets operate within a firm's boundaries, which are usually protected by firewalls and password access. Increasingly, however, these boundaries are drawn to include stakeholders, suppliers and customers in order to allow them to participate in the exchange of knowledge. The intranet can also be used to support a variety of needs, from information sharing among research teams to equipping frontline staff with service details and account backgrounds. In addition, intranet-based electronic point of sales of the different service provided can be implemented to cut across country barriers. Also, by allowing customers to access relevant information and interact directly with the organization, customer knowledge is enhanced by a constant flow of information not only within but also across organizational boundaries.

Technology for knowing what employees know

While capturing knowledge is the objective of the data warehouse, there is a need to complement this with systems that provide access to knowledge or facilitate its transfer among individuals, e.g. software to facilitate group discussions and skills directories. These complementary initiatives recognize that to find the person with the needed knowledge and then successfully transfer it from that person to another are very difficult processes. If a library is a metaphor for conceptualizing data warehouse projects, the Yellow Pages might represent the purpose of access to knowing what employees know, with the technology emphasizing connectivity, access and transfer of individuals’ knowledge through the encouragement of face-to-face interactions.

Skills directory

A skills directory acts as the vehicle that moves, retrieves, points to and enhances the information that travels within an organization. Value is added to this information as it is used, acting as a building block that can later be turned into knowledge by its users. As data can become quickly outdated by the time it is captured and organized, a skills directory should not only take a ‘gather and store’ approach but also act as a pointer to other information sources (i.e. another individual), encouraging the user to contact relevant people to find out more, for example, how a project was done and what additional lessons can be shared, since this information may well not have been captured within a written report.

The skills directory's dual function of ‘gather and store’ and ‘pointer’ approach, enables for a dramatic increase in overall productivity. This is largely due to time savings in having to reinvent the wheel and to make use of current knowledge so that it can be improved upon, thereby helping organizations evolve towards being a truly learning organization. In addition, linking people with like minds and interests would promote innovativeness among staff to produce unique solutions. With the skills directory, users can decide for themselves who the best candidate/candidates is/are to help them add value to their work.

Using groupware

Groupware has long been seen as a way to encourage the sharing of ideas in a much more free-flowing manner than repositories or codified decision-support systems may allow. Collaboration is indeed strongly conducive to knowledge generation and transfer. Groupware facilitates ‘anytime, anywhere’ collaboration spaces.

However, one should not adopt a ‘build it and they will come’ approach. It is necessary to find the right mix of people, process and technology elements and use groupware systems as the backbone for the knowledge-sharing infrastructure. Among the professional services firms, Ernst & Young supports its thousands of knowledge workers with its KnowledgeWeb (KWeb), Arthur Andersen has its Knowledge Xchange and PriceWaterhouse-Cooper its Knowledge View system. Each organization has its own approach, content categories and usage policies, but all rely on the ability to not only represent ideas, but also discuss them.

Implementing knowledge management technology

There is constant bombardment of flyers and e-mails, ‘educating’ us on the various knowledge management tools that are in the market. However, how do we pick the appropriate tools for our organization?

To begin with, implementing a knowledge management system within an organization means analysing its current sources of information and knowledge. This includes not only capturing useful information from wherever it may exist, but also requires analysing e-mails, discussion database logs, as well as sources of customer interactions such as e-mails to customers and minutes of meetings with customers. The phases that a knowledge management effort goes through when capturing knowledge and the activities related to completing each phase are typically: documenting knowledge, sharing knowledge and applying knowledge.

Therefore in general, knowledge management encompasses the broad range of capabilities needed to logically capture, organize, share and use knowledge elements in order to recognize problems and suggest possible solutions. The following are some functions that are crucial for a successful knowledge management implementation. Technology vendors of knowledge management tools must provide solutions that are:

1 Able to capture and organize. The system must be able to capture and categorize knowledge in order of relevance, as well as being able to monitor the validity and accuracy of knowledge stored. The system must also allow for new knowledge to be inserted and the categorization able to recognize and prioritize information according to age.

2 Searchable. The system has to have an in-built search engine able to apply the contents of the database to incoming queries, and be able to match and establish whatever connections or relationships may exist between knowledge elements and query contents. The search engine could also be powerful enough to be Internet enabled. Such a system can match a query and pick external sources of information on the World Wide Web, which may have many pages of information pertinent to the query. The search engine should also be capable of learning with every query, matching future similar queries to past ones, thereby maximizing the reuse of the knowledge elements.

3 Able to recognize the user. Using application specific sources of knowledge within the knowledge management system, individual departments within the organization can have access to department-relevant information. For example, the IT department could have access to IT professional web sites while the finance department could have information sites of specific interests to the finance community.

4 Able to facilitate dissemination and learning. The knowledge management system is ideally capable of supporting multiple channel user access, so that the user (be it on e-mail or through the Web, or other forms such as chat rooms) is able to obtain specific information and knowledge from wherever he or she is and from whatever IT access he or she is using. After using a piece of information, the user should be able to add value of any new experiences learnt through use of the information, and also be able to alter the original information and store it back in the knowledge management system for future users.