2

Process approaches for management

of knowledge and learning

Present-day corporations have become enamoured with processled organization design. It is easy to see why. In the modern day there is general acceptance that the idea of a functional department handing over to another functional department is not the way to organize for work. For instance, gone are the days when the product designer's work was over with the delivery of a set of drawings for the manufacturing managers to make. The ‘handover’ practice of yesteryear recalls situations in which manufacturing personnel would be, quite justifiably, appalled at being asked to produce to a design that gave no consideration to the manufacturing process, product quantities, tooling, etc. These tradition-bound companies were rigid, hierarchical functionalities. They were insular and isolated with poor interfunctional coordination. Managers in these companies found it difficult to get things done because work was fragmented and compartmentalized. Process organization and management appears to provide one way of solving these problems. In the simplest terms, processes can be defined as collections of interlinked tasks and activities that combine to transform inputs into outputs. These inputs and outputs can be as varied as materials, products, information and people.

The reasons why processes may be a solution to the problems of traditional organization design is that they are able to provide an intermediate level of analysis. This overcomes the previous polarities of analysing and managing parts and subparts or adopting the ‘black box’ perspective of managing the whole. In the days before process organization there was a focus either on the trees (individual tasks or activities) or the forest (the organization as a whole). The process approach is able to combine the two, thereby providing a much needed integration of the jigsaw that captures the realities of work practice. This is key to the overall effectiveness of organizational form and function.

The knowledge creation process

In 1995, Nonaka and Takeuchi published what is now one of the key texts on the creation of organizational knowledge. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), making new knowledge available to others should be a central activity for organizations, and is the defining characteristic of the phenomena of knowledge management. Knowledge management at its heart involves the management of social processes at work to enable sharing and transfer of knowledge between individuals. Sveiby (1997) and Nonaka (1994) assert that business managers need to realize that, unlike information, knowledge is embedded in people, and knowledge creation occurs in the process of social interaction.

Knowledge management encapsulates assessing, changing and improving individual skills and competencies and/or behaviour. Knowledge in this sense is a process involving a complex set of interactions between the individual and the organization. An analogy to describe this interactive process is the game of rugby. Rugby provides a metaphor for the speed and flexibility with which companies, especially Japanese, use knowledge when developing new products. As in rugby, the ball gets passed within the team as the latter moves up the field as a unit. The ball being passed around among the team contains a shared understanding of what the company stands for, where it is going, what kind of a world it wants to live in and how to make that world a reality. Highly subjective insights, intuitions and hunches are also embraced, i.e. what the ball contains is ideals, values and emotions. Ball movement in rugby is borne out of the team members’ interplay on the field. It is determined on the spot, based on direct experience and trial and error. It requires an intensive interaction among members of the team. This interactive process is analogous to how total knowledge is created within an organization.

Nonaka and Takeuchi suggest that the process of knowledge creation is a spiral, moving from tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge and back to tacit. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi, knowledge is created in the interaction of explicit and tacit knowledge. The harvesting of tacit knowledge from the individual and transforming it to explicit knowledge renders that knowledge available to a much wider range of individuals. Innovation is formulated in the mind of the individual but the social interaction of the individual with others is often the stimulus for this creativity. Nonaka calls this the ontological dimension of knowledge creation. He states that social interaction creates a forum for nurturing, transforming and legitimizing new knowledge. It is a premise that organizations should amplify this process by enabling social interaction to take place, by providing mechanism and support for these processes to occur.

Nonaka details specific circumstances that must exist in order to propagate knowledge creation in the individual: those of intention, autonomy and fluctuation. Intention is concerned with how individuals approach the world and try to make sense of their environment. Nonaka quotes Edmund Husserl (1968), who determined consciousness to be only in existence when related to an object that the individual was conscious of, or directed his or her attention towards. It arises, endures and disappears with the subject's commitment to an object. For the creation of new knowledge an individual's consciousness of the object in question must be very intimate.

It is interesting to note that knowledge comes about as a result of an individual's understanding of information. This understanding can only be attained when the information is evaluated in the light of that individual's previous knowledge and values, i.e. the lens through which the individual views the information will ultimately affect the knowledge generated. The intention of the mind not only creates the possibility of meaning, but also limits its form. Our paradigms limit our view and our perceptions. If the purest of truths are to be the goal of an organization's created knowledge, then the organization must nurture a neutral atmosphere that welcomes truly free thought. This leads on to Nonaka's second dimension: autonomy.

Increases in autonomy in an organization allow individuals to bring their own paradigms to bear on the problem in hand. It also allows the individual to ascend Maslow's hierarchy of needs to self-actualization or attaining a sense of purpose.

An excellent stimulus to innovation is viewing a problem in a new light. Circulating the problem to a wide number of people and assimilating each view can bring this about. Alternatively, it is possible to artificially stimulate the creative process by introducing a random element event. The design theorist, Victor Papanek (1972), suggests a procedure called ‘cognitive disassociation’. The problem at hand is viewed in the light of a selection of random concepts, which are drawn from a dictionary. These random interventions and connections stimulate the person to think of the problem in the light of the new concept. If the product of this conflict is useful to the individual then the process has successfully introduced stimulus; if not, the process can be repeated and/or the outcome combined with another random selection. Similarly, fluctuation has the effect of throwing a wild card into the pack. If individuals have to question their values, for whatever reason, they may gain new insight into a particular problem from the modified viewpoint they now command. Winograd and Florres (1986) emphasize the role of periodic ‘breakdowns’ in human perception. Breakdowns refer to the interruption of an individual's habitual, comfortable state of being. When faced with a breakdown, individuals have an opportunity to reconsider their fundamental thinking and perceptions, which can be of benefit to a problem.

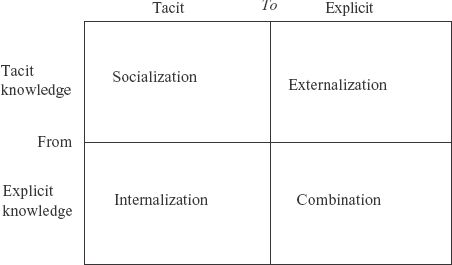

Nonaka (1994), having set the above parameters, goes on to examine the types of knowledge transformation that can come about between the two types of knowledge (tacit and explicit). In this analysis Nonaka develops a matrix, as show in Figure 2.1.

The matrix details the processes that take place when information flows from individuals to others. Nonaka draws the conclusion that while there are specific instances for the socialization, combination and internalization processes there is little research or knowledge about the process of externalization. Additionally, the process of socialization is often ignored because, being a transaction with no documentation, it is difficult to quantify or analyse.

Fig. 2.1 Modes of knowledge generation. Source: Nonaka (1994)

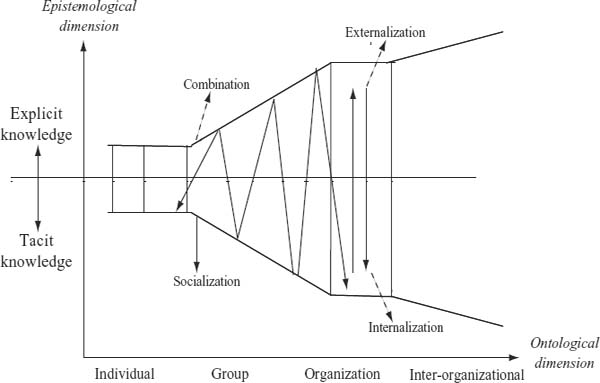

Nonaka suggests that any combination of part of the four processes may leave an incomplete picture of the learning process and fail to cover all the available relevant opportunities for knowledge creation. Rather, a systematic use of all four processes in strict rotation serves to cover all opportunities at each stage. Additionally, the sequence is iterative rather than distinct, i.e. after each full cycle of the four processes, an improvement is made. The process, if continuously repeated, builds knowledge. This precipitates the ‘Spiral of organizational knowledge creation’ (Figure 2.2).

Fig. 2.2 The spiral of knowledge creation. Source: Nonaka (1994)

The spiral starts with socialization when people share their internal knowledge with others, so that tacit knowledge is converted into tacit knowledge. Therefore, the process of knowledge sharing creates new knowledge inside the receiver. Nonaka argues that socialization is the hardest part of capturing tacit knowledge. The next stage in the spiral is externalization, when tacit knowledge is converted or made explicit through metaphors, images and analogies. The third stage Nonaka calls combination, when explicit knowledge is combined with other explicit knowledge to create databases, documents, numbers, spreadsheets and files. The final stage is known as internalization, in which explicit knowledge is converted back to tacit knowledge by operationalizing it through learning by doing and prototyping. Internalization involves knowledge creation transfer through verbalizing or diagramming into documents, manuals and stories.

Nonaka notes that there are certain conditions that propagate the required processes:

1 Creative chaos. This is effectively a motivation factor. The creation of an atmosphere of creative chaos can be genuinely brought about by such things as the rapid loss of market share due to external forces, or artificially created by the setting of tight deadlines. The result is, however, the same, promoting team cohesiveness in the face of adversity.

2 Reflective action. Definition of the problem is of paramount importance but can be adversely affected by the paradigms of the definer. To achieve a true definition one must also examine one's own preconceptions and how they effect the solution.

3 Information redundancy. Redundancy, in this instance, is the over-publication of information, i.e. the dissemination of nonessential information to all participants in a project, rather than selective distribution on a ‘need to know’ basis. In this way the problem is brought to a much wider audience than would normally examine it and, consequently, more differing perspectives can be brought to bear on the problem. Similarly, this sort of information dissemination can overcome hierarchical and departmental barriers.

4 Internal rivalry. This is the division of development staff into multiple teams, each developing a particular concept. The concepts can then, at a later stage, be used as a basis for debate on the merits of each, in conflict with the others. This can generate the social interaction required for knowledge creation.

5 Strategic rotation: The rotation of staff exposes the individual to differing perspectives but also allows him or her to communicate in the language of the others in the organization. In this way organizational knowledge becomes more fluid.

Finally, Nonaka ties these concepts to a theory of organizational structure. In so doing, he joins together several theories of organizational structure to a context-sensitive selection. This suggests that in particular cases it may be favourable to view the organization as a hierarchy. In others, the view of a project-based collective may be more relevant, while in yet others the view of the organization as a collective of tacit and explicit knowledge and skills may be more useful. The point is that these selections can be made to suit the problem. This is described as the ‘hypertext organization’ because of its similarities to a page of hypertext, which can be viewed in several differing ways, each imparting a slightly differing meaning.

Characteristics in the use of tacit knowledge

Knowledge and learning, the source of sustained advantage for most companies, depend upon the individual and collective expertise of employees. Some of this expertise is explicit but most is tacit. The management of tacit knowledge is relatively unexplored, particularly when compared with the work on explicit knowledge. Moreover, while individual creativity is important, exciting and even crucial to business, the creativity of groups is equally important. The creation of today's complex systems of products and services requires the merging of knowledge from diverse national, disciplinary and personal skill-based perspectives. Knowledge, whether it is revealed in new products and services, new processes or new organizational forms, is rarely an individual undertaking.

According to Leonard-Barton and Sensiper (1998), there are three main ways in which tacit knowledge can be potentially exercised to the benefit of the organization:

1 Problem solving. The most common application of tacit knowledge is for problem solving. The reason experts on a given subject can solve a problem more readily than novices is that the experts have in mind a pattern born of experience, which they can overlay on a particular problem and use to quickly detect a solution. The expert recognizes not only the situation in which he or she finds himself or herself, but also what action might be appropriate for dealing with that situation. Writers on the topic note that ‘intuition may be most usefully viewed as a form of unconscious pattern-matching cognition’.

2 Problem finding. A second application of tacit knowledge is to the framing of problems. Some researchers distinguish between problem finding and problem solving. Problem solving is linked to a relatively clearly formulated problem within an accepted paradigm. Problem finding, on the other hand, tends to confront the person with a general sense of intellectual unease leading to a search for better ways of defining or framing the problem. Creative problem framing allows the rejection of the ‘obvious’ or usual answers to a problem in favour of asking a wholly different question. Intuitive discovery is often not simply an answer to the specific problem but is an insight into the real nature of the dilemma.

3 Prediction and anticipation. The deep study of a subject seems to provide an understanding, only partially conscious, of how something works, allowing an individual to anticipate and predict occurrences that are subsequently explored very consciously. Histories of important scientific discoveries highlight that this kind of anticipation, and reliance on inexplicable mental processes can be very important in invention. In stories about prominent scientists, there are frequent references to the ‘hunches’ that occur to the prepared mind, sometimes in dreams, as in the case of Kekule's formulation of the structure of benzene. Authors writing about the stages of creative thought often refer to the preparation and incubation that precede flashes of insight.

Tacit knowledge is best utilized in an environment where learning and the use of personal experience is encouraged. The explication of tacit knowledge is like a subconscious memory recall, which then develops into a ‘feeling’ about the situation (Agor, 1986). Polanyi (1966) refers to this connection as ‘the basic structure of tacit knowing’. He states that we are consciously aware of the memory recall only as it relates to the current cue, which could be either internal or external to the person. Similar to the subconscious recognition of a solution is Melone's (1994) concept of the autonomous stage of learning. At this stage, an individual loses the ability to describe where the knowledge came from. For example, individual learning and experience feeds back into the organization's knowledge base and shapes the dominant logic. So incoming data and experiences are filtered automatically by the dominant logic and the analytical procedures used by managers (Bettis and Prahalad, 1995), until the dominant logic is renewed once again by new learning and knowledge.

Knowledge and learning process

Davenport, Jarvenpaa and Beers (1996), propose that knowledge needs to be managed via a process. However, they highlight that it is difficult to separate a knowledge process from its outcomes. For example, in high-tech organizations, breakthrough products often require the invention of a new process. The product manager has nearly total freedom during the developmental process. The lack of separation between process and outputs is also reflected in the way outputs are valued. The more laborious the process or expensive the input (i.e. expert knowledge workers involved), the more value is placed on the outcome.

In process approaches, effectiveness is typically defined by the value generated for the end-customer. The most frequently used metrics are quantitative assessments of productivity and examining the transformation of tangible inputs to physical outputs. In contrast, in service-related sectors, due to service intangibility, work productivity is measured on the basis of input rather than the effectiveness of transformation. Knowledge and learning share similar difficulties in measurement with service processes. Knowledge work poses challenges, in that the nature of the activity and the people often resist heavily structured and standardized approaches. Therefore, knowledge and learning processes must accommodate openness and adaptability, if knowledge programmes are to succeed.

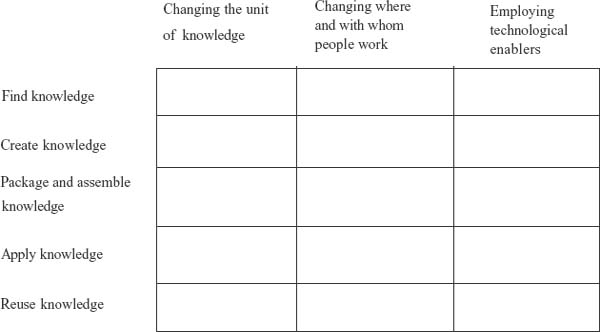

Davenport, Jarvenpaa and Beers (1996), on the basis of their research in thirty projects, identify five primary process orientations to knowledge: acquisition, creation, packaging, application and reuse of knowledge. According to them:

1 Some processes consist of finding existing knowledge, understanding the knowledge requirements, searching for it among multiple sources and passing it along to the user, e.g. competitive intelligence process.

2 Other processes involve creating new knowledge, e.g. activities in a pharmaceutical firm, the creative process in advertising.

3 Knowledge work processes can package or assemble knowledge created externally to the process. Publishing is a good example, since even though it does not create new knowledge, the editing, design and proofreading processes qualify as knowledge work.

4 Certain processes primarily apply or use existing knowledge. In these processes, the creation of new bodies of knowledge might be actively discouraged, e.g. a physician is not normally expected to experiment on a patient to create new knowledge but, rather, to apply existing medical knowledge.

5 Some firms have a primary focus on the reuse of knowledge. They promote learning, but focus on separating it from prior knowledge and leveraging that prior knowledge as much as possible, e.g. in the product development process, use of modular parts reuses existing knowledge about those components.

These different knowledge orientations, in turn, are associated with different objectives and methods for knowledge work improvement. The objectives can vary widely and therefore necessitate different approaches. Davenport, Jarvenpaa and Beers suggest three primary strategies for the redesign of knowledge work:

1 Firms can change knowledge work itself by reducing (or, in some cases, creating) a unit of knowledge that workers can reuse or access or by improving knowledge capture techniques.

2 Firms can improve knowledge work by changing the physical location of where and with whom people work. This change typically involves co-location, new or modified team structures or new roles.

3 Firms can use technology to bolster knowledge work by, among other things, creating knowledge bases and enabling telecommunications infrastructure and applications.

Recalling our earlier thoughts suggests that these knowledge process orientations are only one, albeit important, element of a knowledge management programme. Other factors such as culture, strategy, competitive environment and IT infrastructure can all affect the efficacy of the programme. Only by establishing the relationship between knowledge work process and the overall goals that the company is hoping to move towards is it possible for a manager to assess the types of organizational design to be constructed. This challenge of designing, or improving, the knowledge processes is most easily observed by constructing a matrix of alternative design solutions, or possibilities to move towards via structural re-engineering (see Figure 2.3). The matrix, by drawing out possible alternatives, allows managers to reflect on possibilities, limitations and actions necessary to achieve the selected design solution.

Creating competences through knowledge and learning

The generic goal of the knowledge and learning process is in the development of core competencies to support strategic intent. Managing knowledge and learning helps the company to own, control and properly maintain competencies as state of the art, and also helps it to tailor them to specific projects and business initiatives.

Fig. 2.3 Relationship between knowledge orientation and organizational design. Source: Davenport, Jarvenpaa and Beers (1996)

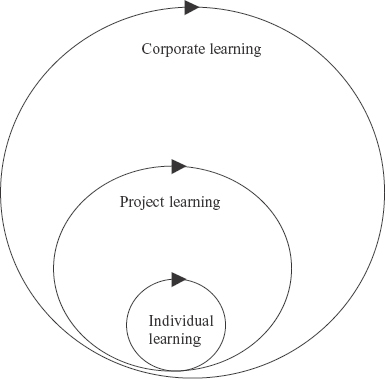

The knowledge and learning process is conceptualized to occur at three different levels: individual, team and corporate (or strategic). In modern corporate settings some individuals (such as scientists involved in basic research) may learn and create in isolation, but for the most part individual competence enhancement occurs within team environments. Teams are organized on a project basis, and teams learn through the experience of completing a project. At completion of a project, experience can be captured and consolidated into the company as part of its corporate intellectual asset (see Figure 2.4). This intellectual asset base can be reused subsequently by individuals and teams to create yet more insight and learning.

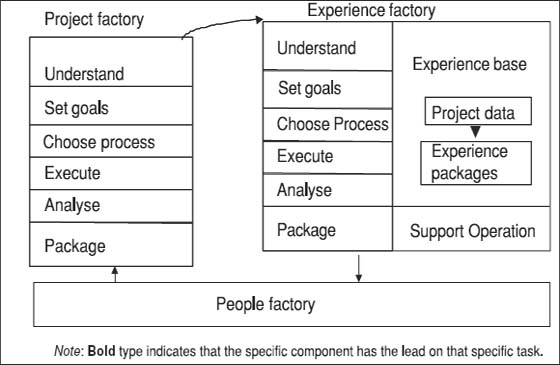

Adapting a number of perspectives (Nevis, Dibella and Gould, 1995; Leonard-Barton, 1992; Roth, Kemp and Doug, 1994) the three levels can be viewed structurally to comprise three essential components: the people factory, the project factory and the experience factory.

Fig. 2.4 The three knowledge-learning improvement levels

Organization as people, project and experience factories

Building a knowledge and learning capability demands the reuse of experience and collective learning. This is best achieved by designing two structures to extend upon individual (people factory) learning. The three structures are:

1 People factory. For an organization to be successful over time it must constantly build competencies in its workforce appropriate to its current and future needs. Knowing its current people competence base and its future needs helps not only long-term planning but also provides guidance to what are the best ways to deploy its human asset base.

2 Project organization. Organizing around a project structure facilitates and capitalizes upon individual learning and skills. Through the execution of projects the organization can build up an experience resource base.

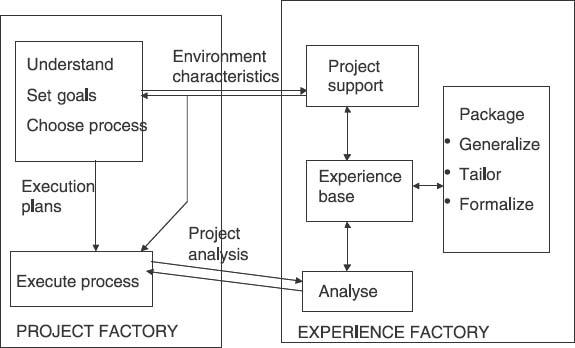

3 Experience factory. This is a knowledge and learning repository. As projects are executed the team gains experiences with products, plans, processes and models that have been used in their attempt to achieve project aims. The data, insight and knowledge gathered during the development and execution of a project can be deposited subsequently in the experience factory. Successes as well as failures are useful learning experiences. They inform you what worked and what did not. The project organization is thus the supply source for the experience factory. The experience factory transforms insights and learning into reusable units (through the process of analysing experiences) and supplies them back to the project organization (through a process of packaging useful insights and knowledge). Analysis involves examining the experience collected, in order to uncover any genuinely new knowledge. Packaging involves taking the new knowledge and converting it into a usable form. This is achieved through three activities: generalize, tailor and formalize. Generalize means taking the knowledge from its specific context and making it more generic. If this can be done then it makes that specific knowledge available for more general use. Tailoring is to customize the knowledge packet to the specific needs of a team, unit or individual. Formalizing a knowledge solution involves taking steps to make the discovered new knowledge a standard throughout the organization, because it is considered to represent best practice. The experience factory can, in addition, provide specific monitoring and consulting support. The experience factory also has a role in keeping the people factory informed about the developing competencies of project team members. The people factory can use this information as a basis of selecting personnel for future engagements.

The experience factory is thus an important part of the knowledge organization. It supports reuse of experience and collective learning by developing, updating and providing ‘packets’ of competencies. These packages of competencies are built from previous ‘learning and knowledge experience’ gleaned from individuals and teams executing projects. The ‘packets’ can be, utilized later by teams to carry out new projects. In this way the company makes effective reuse of its existing knowledge and also updates its corporate learning as new insights are developed from experience.

Personnel in the experience factory sustain and facilitate the interaction between project team members by:

- saving and maintaining information

- making it efficiently retrievable

- controlling and monitoring its access.

The main products of the experience factory are core competencies packaged as aggregates of project development experiences. The company by making these packets amenable can potentially deploy such competencies widely across the organization. The process is, first, one of discovering tacit knowledge and creating new knowledge (via project experience) and, second, one of making knowledge explicit (via the activities of the experience factory). In this interplay (between the individual, the project and the experience factory) a tacit to explicit cycle is constantly turned (Figure 2.5). This interplay facilitates, what Nonaka, terms, the spiral of knowledge creation.

Synergy between the three component structures occurs via the iterations of the knowledge and learning improvement cycle. While all participants go through the knowledge and learning process cycle at each stage, not all play an equivalent role. At times the project factory takes a lead role, at other times the experience factory and on other occasions, the people factory (see Figure 2.6). The knowledge and learning process cycle occurs in six steps:

Fig. 2.5 The inter-linkages between the project factory and experience factory

Step 1: Understanding. The company builds understanding of the environment, within which it lives. This helps it appreciate what projects it needs to undertake for the company to survive and succeed.

Step 2: Set project plans. The company defines the specific aims in alignment with its broader mission and vision of what the company wants to achieve, given the environment in which it resides.

Fig. 2.6 The knowledge-improvement cycle embedded within the three organization structures

Step 3: Choose people, processes, methods and techniques and tools. To achieve its goals the company must decide on the ways it is going to achieve them. This means understanding the problems and tailoring strategies to fit the problem.

Step 4: Execution. After formulating methods the company moves to executing its plans. During execution it analyses the intermediate results and asks if it is satisfying the goals and using appropriate processes. This feedback loop is the first part of project learning.

Step 5: Analysis. After execution of plans is complete the company analyses what happened and learns from it. This becomes part of corporate learning.

Step 6: Packaging. The company stores and propagates the resultant knowledge and experience.

Each turn of the cycle should result in better understanding of the organizational context and capabilities. Improved understanding of the environment leads to better articulation of goals and a better deployment of corporate assets. The better the match between the task at hand and existing capabilities, the better the execution. This results in greater efficiency and effectiveness, which is the essence of any knowledge and learning programme. Each turn either refreshes and rejuvenates existing competencies or builds new ones to be leveraged in the future.

In the initial phases (understand, set goals and choose process) the operation focuses on planning. Here, the people and project factory take a leading role and are supported by the experience factory analysts. The outcome of these of these phases are:

1 On the project factory side: a project plan associated with a management control plan. (The project control plan describes the project's goals, phases and activities with the products, mutual dependencies, milestones and resources. The management control plan indicates the priorities that need to be ‘actioned’ in order to achieve strategic goals.)

2 On the experience factory side: a support plan, which is also associated with the management control framework. (The plan describes the support that it will provide for each phase and activity and expected improvements.)

3 On the people factory side: a project team people plan and competency development plan, linked to the management control plan. (For example, the project team plan indicates the availability of people with requisite skills, and how they will come into play at the various stages of development. The people factory role is also to generate and promote newly acquired competencies from the experience factory into the workforce.)

In the following step (execute), the operation focuses on delivering the ‘product’ assigned to the project organization. Here, the project organization takes a lead role and is supported by the experience factory and people factory. The outcome of this stage is the development of an ‘experience product’, which is associated with a set of potentially reusable products (and/or ‘part’ packets of the product), processes and experiences.

In the remaining phases (analyse and package), the operation concentrates on capturing project experience and making it available to future similar projects. The experience factory has a leading role and is supported by the project organization, which is the source of that experience. The outcomes of these phases are lessons learned with recommendations for future improvements, and new or updated experience packages incorporating the experience gained during project execution. The experience factory then has the role of communicating and disseminating the new knowledge to other people in the company, i.e. it facilitates knowledge-led organizational core competence building.

The knowledge improvement/learning paradigm is an iterative process that repeatedly attempts to build and reinforce competencies. Through each iteration the organization redefines and improves itself. This knowledge and learning paradigm occurs via three major cycles:

1 The skills cycle is the feedback to the individual. It is the process through which individuals past skills and training, and understanding of what works, how it works from specific training and experience, gets updated via a new project experience. During this process some embedded skills may be made transparent (i.e. become explicit). This expertise and learning needs then to be made more widely available (most typically in the project team environment, but it can occur in other formats) to help solve specific business problems.

2 The control cycle is the feedback to the project during the execution phase. It provides analytical information about the project's performance at intermediate stages of the development by comparing the project's data with the average for similar projects. This information is used to prevent and solve problems, monitor and support the project, and realign the project with goals.

3 The capitalization cycle is the feedback to the organization. Its purpose is to understand what happened, how it happened and why it happened. Capitalization involves capturing the experience and devising ways to transfer this experience across application domains. This it does by accumulating reusable experience encapsulated in innovative product, process artefacts and other outcomes, which may prove useful in solving problems in the future.

Structuring the organization as a knowledge and experience factory around project teams in which peoples’ specific competencies can be leveraged and developed, offers the company an opportunity to learn from every project. This way as the company matures, it constantly rejuvenates and reinvigorates itself, with a constant flow of fresh insight and learning. Over the long term, this supports the evolution of the organization from task based, where all activities are aimed at the successful execution of current project tasks, to knowledge and learning capability based. Knowledge and learning based capability endows the company with continuous energy for improvement and change. In other words it makes it adaptive and resilient to its environment.

Types of processes

Garvin (1998) suggests that there are two major categories of generic processes: organizational and managerial.

Organizational processes

Organizational processes can be further divided into three subcategories:

- work processes

- behavioural processes

- change and learning processes.

Work processes

The primary function of work processes is to accomplish tasks. They are based on the organizing principle that work is accomplished through linked chains of activities cutting across departments and functional groups. These chains are called work processes, and can be further categorized into:

- operational processes – processes that create, produce, and deliver products and services that customers want, e.g. new product development, manufacturing, and logistics and distribution

- administrative processes – processes that do not produce outputs that customers want, but are still necessary for running the business, e.g. strategic planning, budgeting and performance measurement.

Typically, operational processes produce goods and services that external customers consume, while administrative processes generate information and plans that internal groups/processes use. The two, therefore, must not be considered as independent and unrelated activities. They must be aligned and mutually supportive if the organization is to function effectively. Unfortunately, there is usually a preoccupation in improving operational processes but a neglect of supportive administrative processes. The outcome of this unbalanced focus often leads to only marginal performance gains.

Behavioural processes

Behavioural processes capture patterns and features of the organization's ways of acting and interacting. They represent the companies ingrained behaviour. Examples are decision-making and communication processes. The underlying patterns are usually so deeply embedded that they are displayed by most organizational members, often without them consciously recognizing the patterns. Behavioural processes also have strong permanency about them and are capable of withstanding turnover of personnel and many organizational upheavals.

In themselves, behavioural processes do not possess an independent existence. Nevertheless they are important because they feature permanently in all processes. They are generalized patterns of the accepted way of doing things, forming a collection, movement and interpretation of information, through people. In most cases, behavioural processes define behaviours that are learnt informally through socialization and on-the-job experience, capturing cognitive and interpersonal aspects of the work. This makes them difficult to identify yet highlights their importance. For example, many new product development processes of different companies roughly share similar work flows yet still involve radically different patterns of decision making and communication. These underlying patterns often determine the effectiveness of the operational process, and its ultimate success or failure.

The most important three behavioural processes are:

Organizational change and learning processes

Organizational learning is a critical facet in the struggle for long-term organizational survival. It involves the creation and acquisition of knowledge and rests ultimately on the development of sharing. Companies often approach this challenge in an abstract and ad hoc way but, as we elaborate in later discussions, within knowledge management processes there exist persistent underlying patterns in the way an organization can and does approach learning and change. Over time these approaches become institutionalized as the organization's dominant mode of knowledge and learning.

Managerial processes

Management is simply the art of getting things done. The reality of the work takes into account that organizations are complex social beings with widely distributed responsibility, resources, politics and power imbalances. Managers spend a large amount of their time working through this maze to get the employees moving in the desired direction. Managers must win support and allegiance from individuals, and harmonize competing interests and goals to get things done. Indeed, it is the actions and mechanics of implementation that constitute the heart of the process approach.

Three broad managerial processes can be defined:

1 Direction-setting processes. Direction-setting, is one of the most common managerial processes. It involves mapping the future and then mobilizing support and ensuring alignment to this agenda.

2 Negotiating and selling processes. To get employees to move in the charted direction, managers must negotiate, persuade and sell the processes necessary to get the job done. These processes need to manage and exploit both horizontal and vertical inter-linkages. Various ways can be used to elicit support, including creating dependence, providing quid pro quo exchanges and appealing to compelling organizational needs.

3 Monitoring and control processes. Once operations are up and running, managers then need to engage in a set of processes designed to ensure the processes conform to requirements.

These control processes are necessary to maintain equilibrium and also to ensure that processes are efficient and effective. To a large extent these are information-driven systems for detecting and controlling process perturbations by initiating corrective actions to restore the organization to its state of equilibrium.

The problem is that many companies fail either to adopt a process perspective or, even when they do, their attention is confined primarily to work processes. Focusing narrowly on work processes without interlacing with all other processes, needless to say, will continue to deliver suboptimal results.

A common problem processes face, even when they are redesigned to represent the state of the art, is when they fail to deliver upon the promise. The sequence often witnessed is that when the process is redesigned there is initial enthusiasm but, once the revised process is documented and the people trained to use it, corporate commitment quickly drops off. You now have a well-designed process but the problem that it is not used. This lack of commitment is often the symptom but not the cause of the problem. The cause usually is that the corporate culture embraces an event perspective rather than a process perspective. Once the process manuals are distributed and users trained, the job is considered done. The failing is that companies often do not realize that the process is an ongoing, culture-embedded, continuously improving living system, thus leading to situations in which the redesigned process merely limps along.

One common way of looking at the process mode of organizational structuring is simply as a series of interlinked activities coordinated and reviewed periodically by management. A better way of looking at processes, however, is also to see them as company-wide decision-making systems. A process is a human-based system that incorporates all business disciplines. It is both defined by the corporate culture and made up of it. Processes enable a company to tap its full potential by engaging the skills, talents and intellectual capabilities of each of its members.

The process context

Learning and knowledge-led organizations are defined simply as groups of people continually enhancing their capacity to create. The knowledge and learning organization is one with an ingrained philosophy for anticipating, reacting and responding to change, complexity and uncertainty. Senge (1990) remarks that practically all conventional management approaches have prevented the natural development and growth of adult individuals, work teams and organizations by creating environments that impede learning and thus prevent employees and organizations from developing to their full potential.

According to Senge (1990) learning organizations are those in which people:

- continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire

- continually learn how to learn together

- share common goals that are larger than individual goals

- function together in extraordinary ways, complementing each other's strengths and compensating each other's limitations as part of a great team.

The significance of knowledge organizations derives from their ability to learn more quickly than competitors, and the ability to shift people's attention from a ‘means to an end’ view of work to a ‘fulfilment’ view, in which people seek intrinsic benefits from work. In this view, employees need to understand that their problems are not caused by someone ‘out there’, but by their own actions as part of a larger system.

In Senge's view, generative learning is about creating learning, it requires systemic thinking, shared vision, personal mastery, team learning and creative tension between the vision and the current reality. According to Senge, the development of a learning organization depends on the mastery of five disciplines. For learning organizations to function properly, all five component disciplines must be effective as an ensemble. These five are useful in defining the broad contextual considerations for knowledge management and learning: systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models, building a shared vision and team learning.

Systems thinking

Systems are interconnected parts or events that resemble a spider's web or a fisherman's net. In a system, each part (which is usually hidden from view) has an influence on the rest of the system. Intervention in one part of a system can have unforeseen effects on the other parts of the system. Therefore, systems can only be understood by contemplating the whole rather than the individual parts.

Systems thinking enables us to make the full patterns of events clearer and to help us to change them effectively. Systems thinking is necessary to balance the human tendency to focus on events or snapshots of isolated parts of a system that may be distant in time and space. According to Senge, systems thinking is the fifth discipline that integrates the other disciplines into a coherent body of theory and practice. It needs the other four to realize its potential. There are two other reasons which indicate the importance of adopting a systems perspective. First, managing change effectively requires changing behaviour patterns (Kanter, Stein and Todd, 1992). This can be most easily accomplished by changing the structure of the system and the rules that make some behaviours easier and others more difficult. Systems thinking enables management to understand better the structure of the existing system. Second, to bring about signifi-cant performance improvement it is important to know where in the system management interventions are most likely to yield results. Using the systems approach to portray an organization's structure makes it easier to identify the points of high leverage. These are the system parts that can be changed with limited effort and bring about maximum possible changes and benefits. Approaching performance improvement using high leverage points in the system not only makes change more efficient, but is likely to lead more easily to breakthrough improvements along a new higher performance curve. What managers must consider is how their actions are likely to affect performance in both the short and the long run. Also, managers must gain insights into ‘hidden from view’ interactions that undermine performance.

Personal mastery

Even in today's business world, very few organizations encourage the growth of their people. However, the foundation of any learning organization is the personal mastery of its members. This is because an organization's capacity for learning cannot exceed that of its members. Personal mastery is the discipline of continually clarifying and deepening personal knowledge, of focusing energies and seeing realities objectively. People with a high level of personal mastery are able to realize consistently the results that matter most to them and the organization.

Mental models

Mental models are the deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations or even pictures or images that influence how we understand the world and how we take action. Very often, we are not consciously aware of the mental models or the effects it has on our behaviour.

Building a shared vision

It is hard for any organization to achieve sustained success without goals, values and a mission. Building a shared vision is the capacity to develop and hold a shared picture of the future. The doors open for success when an organization's leadership manages to bind people together around a common identity and sense of destiny. Organizations cannot be ordered to change, but a powerful vision can pull people in a desired direction.

It is not enough for a leader to have a vision; this vision must be translated into a shared vision that galvanizes an organization to focused action. Building a shared vision involves the skills of unearthing shared pictures of the future that foster genuine commitment and enrolment rather than compliance.

Team learning

Team learning is important because teams, not individuals, are becoming the fundamental unit in modern organizations. When teams really learn, they produce extraordinary results and the members of the team grow more rapidly than otherwise.

The discipline of team learning starts with dialogue. This is the capacity of its members to suspend assumptions and enter into genuine thinking together. Dialogue differs from discussion as it is the free flow of ideas which enables a group to think together. The discipline of dialogue involves learning how to recognize the patterns of interaction in teams, such as defensive routines that undermine genuine learning. Effective dialogue depends on effective communication and the co-ordination of its parts which represent different subcultures (research and development, marketing, production, etc.), through different ‘languages’ and priorities.

Besides the five disciplines, Senge (1990) highlights the importance of the leader in the success of a knowledge programme by emphasizing that the leader's role in a learning company is that of a designer, teacher and steward who can build shared vision and challenge prevailing mental models. He or she is responsible for building organizations where people are continually expanding their capabilities to shape their future, i.e. leaders are responsible for learning. The emphasis is on innovation and the discovery of new ideas. Managers have to develop individual commitment, accountability, ownership, technical excellence plus the ability to work together. Trust is an underlying characteristic that is a fundamental enabler for learning and sharing. It needs to be developed throughout the organization. Without trust, employees hesitate to contribute and the organization will fail in its efforts to manage knowledge and learn.

The final contextual determinant of whether the knowledge and learning programme is likely to be a success or failure is in the way the company processes its managerial experiences. Learning organizations and learning managers learn from their experiences rather than getting bound up in their past experiences. In knowledge and learning environments, the ability of an organization/manager is not measured by what it knows – the product of learning, but rather by how it learns – the process of learning. Management practices should encourage, recognize, and reward openness, systemic thinking, creativity, a sense of efficacy and empathy.

Conclusion

In tomorrow's business world, companies will have to rely on a continuous cycle of learning to capitalize fully on organizational capabilities and continually create new and fresh markets for goods and services. These organizations, the so-called learning or knowledge-led corporations, will be more agile and responsive to their environments. They will build their market success not on traditional economic drivers such as large size, economies of scale and proprietary technology, but on learning and knowledge strategies, and organization designs capable of constantly creating and cultivating new sources of knowledge and ideas to develop products and services. These companies will redefine their industry's landscapes.

Knowledge and learning are part of everyone's task, not just knowledge managers. Knowledge and learning is not just product, it is process, and management.