CHAPTER 3

Building the Innovative Organization

“Innovation has nothing to do with how many R&D dollars you have … it’s not about money. It’s about the people you have, how you’re led, and how much you get it.”

– Steve Jobs, interview with Fortune Magazine, 1981 [1]

“People are our greatest asset.” This phrase – or variations on it – has become one of the clichés of management presentations, mission statements, and annual reports throughout the world. Along with concepts such as “empowerment” and “team working,” it expresses a view of people being at the creative heart of the enterprise. But very often the reader of such words – and particularly those “people” about whom they are written – may have a more cynical view, seeing organizations still operating as if people were part of the problem rather than the key to its solution.

In the field of innovation, this theme is of central importance. It is clear from a wealth of psychological research that every human being comes with the capability to find and solve complex problems, and where such creative behavior can be harnessed among a group of people with differing skills and perspectives extraordinary things can be achieved. We can easily think of examples. At the individual level, innovation has always been about exceptional characters who combine energy, enthusiasm, and creative insight to invent and carry forward new concepts, such as James Dyson, with his alternative approaches to domestic appliance design; Spence Silver, the 3M chemist who discovered the nonsticky adhesive behind “Post-it” notes; and Shawn Fanning, the young programmer who wrote the Napster software and almost single-handedly shook the foundations of the music industry.

Innovation is increasingly about teamwork and the creative combination of different disciplines and perspectives. Whether it is in designing a new car in half the usual time; bringing a new computer game to market; establishing new ways of delivering old services such as banking, insurance, or travel services; or putting men and women routinely into space; the success comes from people working together in high-performance teams.

This effect, when multiplied across the organization, can yield surprising results. In his work on US companies, Jeffrey Pfeffer notes the strong correlation between proactive people management practices and the performance of firms in a variety of sectors [2]. A comprehensive review for the UK Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development suggested that “… more than 30 studies carried out in the UK and US since the early 1990s leave no room to doubt that there is a correlation between people management and business performance, that the relationship is positive, and that it is cumulative: the more and the more effective the practices, the better the result [3].” Similar studies confirm the pattern in German firms [4]. In a knowledge economy where creativity is at a premium, people really are the most important assets which a firm possesses. The management challenge is how to go about building the kind of organizations in which such innovative behavior can flourish.

This chapter deals with the creation and maintenance of an innovative organizational context, one whose structure and underlying culture – that is, the pattern of values and beliefs – support innovation. It is easy to find prescriptions for innovative organizations that highlight the need to eliminate stifling bureaucracy, unhelpful structures, brick walls blocking communication, and other factors stopping the flow of good ideas. However, we must be careful not to fall into the chaos trap – not all innovation works in organic, loose, informal environments, or “skunk works” – and these types of organization can sometimes act against the interests of successful innovation. We need to determine appropriate organization – that is, the most suitable organization given the operating contingencies. Too little order and structure may be as bad as too much.

Equally, “innovative organization” implies more than a structure or process; it is an integrated set of components that work together to create and reinforce the kind of environment that enables innovation to flourish. Studies of innovative organizations have been extensive, although many can be criticized for taking a narrow view, or for placing too much emphasis on a single prescription like “team working” or “loose structures.” Nevertheless, it is possible to draw out from these a set of components that appear linked with success; these are outlined in Table 3.1 and explored in the subsequent discussion.

TABLE 3.1 Components of the Innovative Organization

| Component | Key Features | Example References |

| Shared vision, leadership, and the will to innovate |

Clearly articulated and shared sense of purpose Stretching strategic intent “Top management commitment” |

[5–8] |

| Appropriate structure | Organization design that enables creativity, learning, and interaction. Not always a loose “skunk works” model; key issue is finding appropriate balance between “organic and mechanistic” options for particular contingencies | [9−15] |

| Key individuals | Promoters, champions, gatekeepers, and other roles that energize or facilitate innovation | [9,16,17] |

| Effective team working |

Appropriate use of teams (at local, cross-functional, and inter-organizational level) to solve problems Requires investment in team selection and building |

[18−20] |

| High-involvement innovation | Participation in organization-wide continuous improvement activity | [21,22] |

| Creative climate | Positive approach to creative ideas, supported by relevant motivation systems | [7,8,23,24] |

| External focus | Internal and external customer orientation | [25−27] |

| Extensive networking |

3.1 Shared Vision, Leadership, and the Will to Innovate

Innovation is essentially about learning and change and is often disruptive, risky, and costly. So, as Case Study 3.1 shows, it is not surprising that individuals and organizations develop many different cognitive, behavioral, and structural ways of reinforcing the status quo. Innovation requires energy to overcome this inertia and the determination to change the order of things. We see this in the case of individual inventors who champion their ideas against the odds, in entrepreneurs who build businesses through risk-taking behavior, and in organizations that manage to challenge the accepted rules of the game.

The converse is also true – the “not-invented-here” problem, in which an organization fails to see the potential in a new idea, or decides that it does not fit with its current pattern of business. In other cases, the need for a change is perceived, but the strength or saliency of the threat is underestimated. For example, during the 1980s, General Motors found it difficult to appreciate and interpret the information about Japanese competition, preferring to believe that their access in US markets was due to unfair trade policies rather than recognizing the fundamental need for process innovation, which the “lean manufacturing” approach that was pioneered in Japan was bringing to the car industry [28]. Christensen, in his studies of hard drives [29], and Tripsas and Gravetti, in their analysis of the problems Polaroid faced in making the transition to digital imaging, provide powerful evidence to show the difficulties faced by the established firms in interpreting the signals associated with a new and potentially disruptive technology [30].

This is also where the concept of “core rigidities” becomes important [31]. We have become used to seeing core competencies as a source of strength within the organization, but the downside is that the mindset, which is being highly competent in doing certain things, can also block the organization from changing its mind. Thus, ideas that challenge the status quo face an uphill struggle to gain acceptance; innovation requires considerable energy and enthusiasm to overcome barriers of this kind. One of the concerns in successful innovative organizations is finding ways to ensure that individuals with good ideas are able to progress them without having to leave the organization to do so [9]. Chapter 12 discusses the theme of “intrapreneurship” in more detail.

Changing mindset and refocusing organizational energies require the articulation of a new vision, and there are many cases where this kind of leadership is credited with starting or turning round organizations. Examples include Bill Gates (Microsoft), Steve Jobs (Pixar/Apple) [10], Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Elon Musk (Tesla), and Andy Grove (Intel) [11]. While we must be careful of vacuous expressions of “mission” and “vision,” it is also clear that in cases like these there has been a clear sense of, and commitment to, shared organizational purpose arising from such leadership.

“Top management commitment” is a common prescription associated with successful innovation; the challenge is to translate the concept into reality by finding mechanisms that demonstrate and reinforce the sense of management involvement, commitment, enthusiasm, and support. In particular, there needs to be a long-term commitment to major projects, as opposed to seeking short-term returns. Since much of innovation is about uncertainty, it follows that returns may not emerge quickly and that there will be a need for “patient money.” This may not always be easy to provide, especially when demands for shorter term gains by shareholders have to be reconciled with long-term technology development plans. One way of dealing with this problem is to focus not only on returns on investment but also on other considerations such as future market penetration and growth or the strategic benefits. Research Note 3.1 and Case Study 3.2 provide examples of such leadership.

A part of this pattern is also the acceptance of risk by the top management. Innovation is inherently uncertain and will inevitably involve failures as well as successes. Thus, successful management requires that the organization be prepared to take risks and to accept failure as an opportunity for learning and development. This is not to say that unnecessary risks should be taken – rather, as Robert Cooper suggests, the inherent uncertainty in innovation should be reduced where possible through the use of information collection and research [12].

We should not confuse leadership and commitment with always being the active change agent. In many cases, innovation happens in spite of the senior management within an organization, and success emerges as a result of guerrilla tactics rather than a frontal assault on the problem. Much has been made of the dramatic turnaround in IBM’s fortunes under the leadership of Lou Gerstner who took the ailing giant firm from a crisis position to one of leadership in the IT services field and an acknowledged pioneer of e-business. But closer analysis reveals that the entry into e-business was the result of a bottom-up team initiative led by a programmer named Dave Grossman. It was his frustration with the lack of response from his line managers that eventually led to the establishment of a broad coalition of people within the company who were able to bring the idea into practice and establish IBM as a major e-business leader. The message for senior management is as much about leading by creating space and support within the organization as it is about direct involvement.

The contributions that the leaders make to the performance of their organizations can be significant. Upper echelons theory argues that decisions and choices by top management have an influence on the performance of an organization (positive or negative!), through their assessment of the environment, strategic decision making, and support for innovation. The results of different studies vary, but the reviews of research on leadership and performance suggest that the leadership directly influences around 15% of the differences found in the performance of businesses and contributes around an additional 35% through the choice of business strategy [13]. Therefore, both direct and indirect leadership can account for half of the variance in performance observed across organizations. At higher levels of management, the problems to be solved are more likely to be ill-defined, demanding leaders to conceptualize more.

Researchers have identified a long list of characteristics that might have something to do with being effective in certain situations, which typically include the following traits [14]:

- bright, alert, and intelligent

- seek responsibility and take charge

- skillful in their task domain

- administratively and socially competent

- energetic, active, and resilient

- good communicators

Although these lists may describe some characteristics of some leaders in certain situations, measures of these traits yield highly inconsistent relationships with being a good leader [15]. In short, there is no brief and universal list of enduring traits that all good leaders must possess under all conditions.

Studies in different contexts identify not only the technical expertize of leadership influencing group performance but also broader cognitive ability, such as creative problem-solving and information-processing skills. For example, studies of groups facing novel, ill-defined problems confirm that both expertize and cognitive-processing skills are key components of creative leadership and are both associated with effective performance of creative groups [32]. Moreover, this combination of expertize and cognitive capacity is critical for the evaluation of others’ ideas. A study of scientists found that they most valued their leader’s inputs at the early stages of a new project, when they were formulating their ideas, and defining the problems, and later at the stage where they needed feedback and insights into the implications of their work. Therefore, a key role of creative leadership in such environments is to provide feedback and evaluation, rather than to simply generate ideas [33]. This evaluative role is critical, but is typically seen as not being conducive to creativity and innovation, where the conventional advice is to suspend judgement to foster idea generation. Also, it suggests that the conventional linear view that evaluation follows idea generation may be wrong. Evaluation by creative leadership may precede idea generation and conceptual combination. Research Note 3.2 identifies the contribution of diversity in senior management teams.

The quality and nature of the leader–member exchange (LMX) has also been found to influence the creativity of subordinates [34]. A study of 238 knowledge workers from 26 project teams in high-technology firms identified not only a number of positive aspects of LMX, including monitoring, clarifying, and consulting, but also found that the frequency of negative LMX was as high as the positive, around a third of respondents reporting these [35]. Therefore, LMX can either enhance or undermine subordinates’ sense of competence and self-determination. However, the analysis of exchanges perceived to be negative and positive revealed that it was typically how something was done rather than what was done, which suggests that task and relationship behaviors in leadership support and LMX are intimately intertwined, and that negative behaviors can have a disproportionate negative influence. Research Note 3.3 shows how LMX contributes to individual innovation performance.

Intellectual stimulation by leaders has a stronger effect on the organizational performance under conditions of perceived uncertainty. Intellectual stimulation includes behaviors that increase others’ awareness of and interest in problems and develops their propensity and ability to tackle problems in new ways. It is also associated with the commitment to an organization [36]. Stratified system theory (SST) focuses on the cognitive aspects of leadership and argues that conceptual capacity is associated with superior performance in strategic decision making where there is a need to integrate complex information and think abstractly in order to assess the environment. It is also likely to demand a combination of these problem-solving capabilities and social skills, as leaders will depend upon others to identify and implement solutions [37]. This suggests that under conditions of environmental uncertainty, the contribution of leadership is not simply, or even primarily, to inspire or build confidence, but rather to solve problems and make appropriate strategic decisions.

Rafferty and Griffin propose other subdimensions to the concept of transformational leadership that may have a greater influence on creativity and innovation, including articulating a vision and inspirational communication [36]. They define a vision as “the expression of an idealized picture of the future based around organizational values,” and inspirational communication as “the expression of positive and encouraging messages about the organization, and statements that build motivation and confidence.” They found that the expression of a vision has a negative effect on followers’ confidence, unless accompanied with inspirational communication. Mission awareness increases the probability of success of R&D projects, but the effects are stronger at the earlier stages: in the planning and conceptual stage, mission awareness explained two-thirds of the subsequent project success [38]. Leadership clarity is associated with clear team objectives, high levels of participation, commitment to excellence, and support for innovation [39].

The creative leader needs to be much more than simply provide a passive, supportive role to encourage creative followers. Perceptual measures of leaders’ performance suggest that in a research environment the perception of a leader’s technical skill is the single best predictor of research group performance, explaining around half of innovation performance [40]. Keller found that the type of project moderates the relationships between leadership style and project success and found that transformational leadership was a stronger predictor in research projects than in development projects [41]. This strongly suggests that certain qualities of transformational leadership may be most appropriate under conditions of high complexity, uncertainty, or novelty, whereas a transactional style has a positive effect in an administrative context, but a negative effect in a research context [42]. Research Note 3.4 reviews the research on the components of innovation leadership and identifies the most significant characteristics needed.

3.2 Appropriate Organizational Structure

No matter how well developed the systems are for defining and developing innovative products and processes, they are unlikely to succeed unless the surrounding organizational context is favorable. Achieving this is not easy, and it involves creating the organizational structures and processes that enable technological change to thrive. For example, rigid hierarchical organizations in which there is a little integration between functions and where communication tends to be top-down and one-way in character are unlikely to be very supportive of the smooth information flows and cross-functional cooperation recognized as being important factors for success.

Much of the innovation research recognizes that the organizational structures are influenced by the nature of tasks to be performed within the organization. In essence, the less programmed and more uncertain the tasks, the greater the need for flexibility around the structuring of relationships [43]. For example, activities such as production, order processing, and purchasing are characterized by decision making that is subject to little variation. (Indeed in some cases, these decisions can be automated through employing particular decision rules embodied in computer systems.) But others require judgement and insight and vary considerably from day to day – and these include those decisions associated with innovation. Activities of this kind are unlikely to lend themselves to routine, structured, and formalized relationships, but instead require flexibility and extensive interaction. Several writers have noted this difference between what have been termed “programmed” and “nonprogrammed” decisions and argued that the greater the level of nonprogrammed decision making, the more the organization needs a loose and flexible structure [44].

In the late 1950s, considerable work was done on this problem by researchers Tom Burns and George Stalker, who outlined the characteristics of what they termed “organic” and “mechanistic” organizations [45]. The former are essentially environments suited to conditions of rapid change while the latter are more suited to stable conditions – although these represent poles on an ideal spectrum they do provide useful design guidelines about organizations for effective innovation. Other studies include those of Rosabeth Moss-Kanter [46] and Hesselbein et al. [5].

The relevance of Burns and Stalker’s model can be seen in an increasing number of cases where organizations have restructured to become less mechanistic. For example, General Electric in the United States underwent a painful but ultimately successful transformation, moving away from a rigid and mechanistic structure to a looser and decentralized form [11]. ABB, the Swiss–Swedish engineering group, developed a particular approach to their global business based on operating as a federation of small businesses, each of which retained much of the organic character of small firms [6]. Other examples of radical changes in structure include the Brazilian white goods firm Semco and the Danish hearing aid company Oticon [47]. But again we need to be careful – what works under one set of circumstances may diminish in value under others. While models such as that deployed by ABB helped at the time, later developments meant that these proved less appropriate and were insufficient to deal with new challenges emerging elsewhere in the business.

Related to this work has been another strand that looks at the relationship between different environments and organizational form. Once again, the evidence suggests that the higher the uncertainty and complexity in the environment, the greater the need for flexible structures and processes to deal with it [48]. This partly explains why some fast-growing sectors, for example, electronics or biotechnology, are often associated with more organic organizational forms, whereas mature industries often involve more mechanistic arrangements.

One important study in this connection was that originally carried out by Lawrence and Lorsch looking at product innovation. Their work showed that innovation success in mature industries such as food packaging and growing sectors such as plastics depended on having structures that were sufficiently differentiated (in terms of internal specialist groups) to meet the needs of a diverse marketplace. But success also depended on having the ability to link these specialist groups together effectively so as to respond quickly to market signals; they reviewed several variants on coordination mechanisms, some of which were more or less effective than others. Better coordination was associated with more flexible structures capable of rapid response [49].

We can see clear application of this principle in the current efforts to reduce “time to market” in a range of businesses [50]. Rapid product innovation and improved customer responsiveness are being achieved through extensive organizational change programs involving parallel working, early involvement of different functional specialists, closer market links and user involvement, and through the development of team working and other organizational aids to coordination.

Another strand of work, which has had a strong influence on the way we think about organizational design, was that originated by Joan Woodward associated with the nature of the industrial processes being carried out [51]. Her studies suggested that structures varied between industries with a relatively high degree of discretion (such as small batch manufacturing) through to those involving mass production where more hierarchical and heavily structured forms prevailed. Other variables and combinations, which have been studied for their influence on structure, include size, age, and company strategy [52]. In the 1970s, the extensive debate on organization structure began to resolve itself into a “contingency” model. In essence, this view argues that there is no single “best” structure, but that successful organizations tend to be those which develop the most suitable “fit” between structure and operating contingencies.

The Canadian writer Henry Mintzberg drew much of the work on structure together and proposed a series of archetypes that provide templates for the basic structural configurations into which firms are likely to fall [53]. These categories – and their implications for innovation management – are summarized in Table 3.2. Case Study 3.3 gives an example of the importance of organizational structure and the need to find appropriate models.

TABLE 3.2 Mintzberg’s Structural Archetypes

Therefore, a key challenge for managing innovation is one of fit – of getting the most appropriate structural form for the particular circumstances. The increasing importance of innovation and the consequent experience of high levels of change across the organization have begun to pose a challenge for organizational structures normally configured for stability. Thus, traditional machine bureaucracies – typified by the car assembly factory – are becoming more hybrid in nature, tending toward what might be termed a “machine adhocracy” with creativity and flexibility (within limits) being actively encouraged. The case of “lean production” with its emphasis on team working, participation in problem solving, flexible cells, and flattening of hierarchies is a good example, where there is significant loosening of the original model to enhance innovativeness [54].

| Organization Archetype | Key Features | Innovation Implications |

| Simple structure | Centralized organic type – centrally controlled but can respond quickly to changes in the environment. Usually small and often directly controlled by one person. Designed and controlled in the mind of the individual with whom decision-making authority rests. Strengths are speed of response and clarity of purpose. Weaknesses are the vulnerability to individual misjudgement or prejudice and resource limits on growth | Small start-ups in high technology – “garage businesses” – are often simple structures. Strengths are in energy, enthusiasm, and entrepreneurial flair – simple structure innovating firms are often highly creative. Weaknesses are in long-term stability and growth and overdependence on key people who may not always be moving in the right business direction |

| Machine bureaucracy | Centralized mechanistic organization controlled centrally by systems. A structure designed like a complex machine with people seen as cogs in the machine. Design stresses the function of the whole and specialization of the parts to the point where they are easily and quickly interchangeable. Their success comes from developing effective systems that simplify tasks and routinize behavior. Strengths of such systems are the ability to handle complex integrated processes like vehicle assembly. Weaknesses are the potential for alienation of individuals and the buildup of rigidities in inflexible systems | Machine bureaucracies depend on specialists for innovation, and this is channelled into the overall design of the system. Examples include fast food (McDonald’s), mass production (Ford), and large-scale retailing (Tesco), in each of which there is considerable innovation, but concentrated on specialists and impacting at the system level. Strengths of machine bureaucracies are their stability and their focus of technical skills on designing the systems for complex tasks. Weaknesses are their rigidities and inflexibility in the face of rapid change and the limits on innovation arising from nonspecialists |

| Divisionalized form | Decentralized organic form designed to adapt to local environmental challenges. Typically associated with larger organizations, this model involves specialization into semi-independent units. Examples would be strategic business units or operating divisions. Strengths of such a form are the ability to attack particular niches (regional, market, product, etc.) while drawing on central support. Weaknesses are the internal frictions between divisions and the center | Innovation here often follows a “core and periphery” model in which R&D of interest to the generic nature is carried out in central facilities while more applied and specific work is carried out within the divisions. Strengths of this model include the ability to concentrate on developing competency in specific niches and to mobilize and share knowledge gained across the rest of the organization. Weaknesses include the “centrifugal pull” away from central R&D toward applied local efforts and the friction and competition between divisions that inhibits sharing of knowledge |

| Professional bureaucracy | Decentralized mechanistic form, with power located with individuals but coordination via standards. This kind of organization is characterized by relatively high levels of professional skills and is typified by specialist teams in consultancies, hospitals, or legal firms. Control is largely achieved through consensus on standards (“professionalism”), and individuals possess a high degree of autonomy. Strengths of such an organization include high levels of professional skill and the ability to bring teams together | This kind of structure typifies design and innovation consulting activity within and outside organizations. The formal R&D, IT, or engineering groups would be good examples of this, where technical and specialist excellence is valued. Strengths of this model are in technical ability and professional standards. Weaknesses include difficulty of managing individuals with high autonomy and knowledge power |

| Adhocracy | Project type of organization designed to deal with instability and complexity. Adhocracies are not always long-lived, but offer a high degree of flexibility. Team based, not only with high levels of individual skill but also the ability to work together. Internal rules and structure are minimal and subordinate to getting the job done. Strengths of the model are its ability to cope with high levels of uncertainty and its creativity. Weaknesses include the inability to work together effectively due to unresolved conflicts and a lack of control due to lack of formal structures or standards | This is the form most commonly associated with innovative project teams – for example, in new product development or major process change. The NASA project organization was one of the most effective adhocracies in the program to land a man on the moon; significantly the organization changed its structure almost once a year during the 10-year program, to ensure it was able to respond to the changing and uncertain nature of the project. Strengths of adhocracies are the high levels of creativity and flexibility – the “skunk works” model advocated in the literature. Weaknesses include lack of control and over commitment to the project at the expense of the wider organization |

| Mission oriented | Emergent model associated with shared common values. This kind of organization is held together by members sharing a common and often altruistic purpose – for example, in voluntary and charity organizations. Strengths are high commitment and the ability of individuals to take initiatives without reference to others because of shared views about the overall goal. Weaknesses include lack of control and formal sanctions | Mission-driven innovation can be highly successful, but requires energy and a clearly articulated sense of purpose. Aspects of total quality management and other value-driven organizational principles are associated with such organizations, with a quest for continuous improvement driven from within rather than in response to external stimulus. Strengths lie in the clear sense of common purpose and the empowerment of individuals to take initiatives in that direction. Weaknesses lie in overdependence on key visionaries to provide clear purpose and lack of “buy-in” to the corporate mission |

3.3 Key Individuals

Another important element is the presence of key enabling figures. Such key figures or champions have been associated with many famous innovations – for example, the development of Pilkington’s float glass process or Edwin Land and the Polaroid photographic system [55]. Case Study 3.4 gives another example of the role of key individuals, James Dyson. One clear example of such individual contribution comes, of course, from start-up entrepreneurs who demonstrate considerable abilities not only around recognizing opportunities but also in configuring networks and finding resources to enable them to take those ideas forward.

There are, in fact, several roles that key figures can play, which have a bearing on the outcome of a project. First, there is the source of critical technical knowledge – often the inventor or team leader responsible for an invention. They will have the breadth of understanding of the technology behind the innovation and the ability to solve the many development problems likely to emerge in the long haul from laboratory or drawing board to full scale. The contribution here is not only of technical knowledge but it also involves inspiration when particular technological problems appear insoluble and motivation and commitment.

Influential though such technical champions might be, they may not be able to help an innovation progress unaided through the organization. Not all problems are technical in nature; other issues such as procuring resources or convincing sceptical or hostile critics elsewhere in the organization may need to be dealt with. Here our second key role emerges – that of organizational sponsor.

Typically, this person has power and influence and is able to pull the various strings of the organization (often from a seat on the board); in this way, many of the obstacles to an innovation’s progress can be removed or the path at least smoothed. Such sponsors do not necessarily need to have a detailed technical knowledge of the innovation (although this is clearly an asset), but they do need to believe in its potential.

Recent exploration of the product development process has highlighted the important role played by the team members and in particular the project team leader. There are close parallels to the champion model: influential roles range from what Clark and Fujimoto call “heavyweight” project managers who are deeply involved and have the organizational power to make sure things come together, through to the “lightweight” project manager whose involvement is more distant. Research on Japanese product development highlights the importance of the shusha or team leader; in some companies (such as Honda), the shusha is empowered to override even the decisions and views of the chief executive [56]! The important message here is to match the choice of project manager type to the requirements of the situation – and not to use the “sledgehammer” of a heavyweight manager for a simple task.

Key roles are not just on the technical and project management side: studies of innovation (going right back to Project SAPPHO and its replications) also highlighted the importance of the “business innovator,” someone who could represent and bring to bear the broader market or user perspective [16].

Although innovation history is full of examples where such key individuals – acting alone or in tandem – have had a marked influence on success, we should not forget that there is a downside as well. Negative champions – project assassins – can also be identified, whose influence on the outcome of an innovation project is also significant but in the direction of killing it off. For example, there may be internal political reasons why some parts of an organization do not wish for a particular innovation to progress – and through placing someone on the project team or through lobbying at board level or in other ways a number of obstacles can be placed in its way. Equally, our technical champion may not always be prepared to let go of their pet idea, even if the rest of the organization has decided that it is not a sensible direction in which to progress. Their ability to mobilize support and enthusiasm and to surmount obstacles within the organization can sometimes lead to wrong directions being pursued, or the continued chasing up what many in the organization see as a blind alley.

One other type of key individual is that of the “technological gatekeeper.” Innovation is about information and, as we saw earlier, success is strongly associated with good information flow and communication. Research has shown that such networking is often enabled by key individuals within the organization’s informal structure who act as “gatekeepers” – collecting information from various sources and passing it on to the relevant people who will be best able or most interested to use it. Thomas Allen, working at MIT, made a detailed study of the behavior of engineers during the large-scale technological developments surrounding the Apollo rocket program. His studies highlighted the importance of informal communications in successful innovation and drew particular attention to gatekeepers – who were not always in formal information management positions but who were well connected in the informal social structure of the organization – as key players in the process [17].

This role is becoming of increasing importance in the field of knowledge management where there is growing recognition that enabling effective sharing and communication of valuable knowledge resources is not simply something that can be accomplished by advanced IT and clever software – there is a strong interpersonal element [57]. Such approaches become particularly important in distributed or virtual teams where “managing knowledge spaces” and the flows across them are of significance [58]. Research Note 3.5 identifies different individual roles in promoting innovation within organizations.

3.4 High Involvement in Innovation

Whereas innovation is often seen as the province of specialists in R&D, marketing, design, or IT, the underlying creative skills and problem-solving abilities are possessed by everyone. If mechanisms can be found to focus such abilities on a regular basis across the entire company, the resulting innovative potential is enormous. Although each individual may only be able to develop limited, incremental innovations, the sum of these efforts can have far-reaching impacts.

A good illustration of this is the “quality miracle,” which was worked by the Japanese manufacturing industry in the postwar years, and which owed much to what they term kaizen – continuous improvement. Firms such as Toyota and Matsushita receive millions of suggestions for improvements every year from their employees – and the vast majority of these are implemented [59]. Individual case studies confirm this pattern in a number of countries. As one UK manager put it, “Our operating costs are reducing year on year due to improved efficiencies. We have seen a 35% reduction in costs within two and a half years by improving quality. There are an average of 21 ideas per employee today compared to nil in 1990. Our people have accomplished this.” Case Study 3.5 provides another example of high-involvement innovation.

Although high-involvement schemes of this kind received considerable publicity in the late twentieth century, associated with total quality management and lean production, they are not a new concept. For example, Denny’s Shipyard in Dumbarton, Scotland, had a system that asked workers (and rewarded them for) “any change by which work is rendered either superior in quality or more economical in cost” – back in 1871. John Patterson, founder of the National Cash Register Company in the USA, started a suggestion and reward scheme aimed at harnessing what he called “the hundred-headed brain” around 1894.

Since much of such employees’ involvement in innovation focuses on incremental changes, it is tempting to see its effects as marginal. Studies show, however, that when taken over an extended period, it is a significant factor in the strategic development of the organization [60].

Underpinning such continuous incremental innovation are higher levels of participation in innovation. For example:

- In the field of quality management, it became clear that major advantages could accrue from better and more consistent quality in products and services. Crosby’s work on quality costs suggested the scale of the potential savings (typically 20–40% of total sales revenue), and the experience of many Japanese manufacturers during the postwar period provide convincing arguments in favor of this approach [61].

- The concept of “lean thinking” has diffused widely during the past 20 years and is now applied in manufacturing and services as diverse as chemicals production, hospital management, and supermarket retailing [62]. It originally emerged from detailed studies of assembly plants in the car industry, which highlighted significant differences between the best and the average plants along a range of dimensions, including productivity, quality, and time. Efforts to identify the source of these significant advantages revealed that the major differences lay not in higher levels of capital investment or more modern equipment, but in the ways in which production was organized and managed [28]. The authors of the study concluded:

- … our findings were eye-opening. The Japanese plants require one-half the effort of the American luxury-car plants, half the effort of the best European plant, a quarter of the effort of the average European plant, and one-sixth the effort of the worst European luxury car producer. At the same time, the Japanese plant greatly exceeds the quality level of all plants except one in Europe – and this European plant required four times the effort of the Japanese plant to assemble a comparable product…

- Central to this alternative model was an emphasis on team working and participation in innovation.

- The principles underlying “lean thinking” had originated in experiences with what were loosely called “Japanese manufacturing techniques [63].” This bundle of approaches (which included umbrella ideas like “just-in-time” and specific techniques like poke yoke) were credited with having helped Japanese manufacturers gain significant competitive edge in sectors as diverse as electronics, motor vehicles, and steel making [64]. Underpinning these techniques was a philosophy that stressed high levels of employee involvement in the innovation process, particularly through sustained incremental problem solving – kaizen [21].

The transferability of such ideas between locations and into different application areas has also been extensively researched. It is clear from these studies that the principles of “lean” manufacturing can be extended into supply and distribution chains into product development and R&D and into service activities and operations [65]. Nor is there any particular barrier in terms of national culture: high-involvement approaches to innovation have been successfully transplanted to a number of different locations. Case Study 3.6 charts the adoption of high-involvement innovation in different organizations.

Company level studies support this view. Ideas UK is an independent body that offers advice and guidance to firms wishing to establish and sustain employee involvement programs. It grew out of the UK Suggestion Schemes Association and offers an opportunity for firms to learn about and share experiences with high-involvement approaches. Its 2009 annual survey of around 160 organizational members highlighted cost savings of over £100m with the average implemented idea being worth £1400, giving a return on investment of around 5 to 1. Participation rates across the workforce are around 28%.

Specific examples include the Siemens Standard Drives (SSD) suggestion scheme that generates ideas that save the company about £750,000 a year. The electrical engineering giant receives about 4000 ideas per year, of which approximately 75% are implemented. Pharmaceutical company Pfizer’s scheme generates savings of around £250,000, and the Chessington World of Adventures’ ideas scheme saves around £50,000. Much depends on firm size, of course – for example, the BMW Mini plant managed savings close to £10m at its plant in Cowley which they attribute to employee involvement.

Similar data can be found in other countries – for example, a study conducted by the Employee Involvement Association in the United States suggested that companies can expect to save close to £200 annually per employee by implementing a suggestion system. Ideas America report around 6000 schemes operating. In Germany, specific company savings reported by Zentrums Ideen management include (2010 figures) Deutsche Post DHL €220m, Siemens €189m, and Volkswagen €94m. Importantly, the benefits are not confined to large firms – among SMEs were Takata Petri €6.3m, Herbier Antriebstechnik €3.1m, and Mitsubishi Polyester Film €1.8m. In a survey of 164 German and Austrian firms representing 1.5m workers, they found around 20% (326,000) workers involved and contributing just under 1 million ideas. Of these, two-thirds were implemented producing savings of €1.086bn. The investment needed to generate these was of the order of €109m giving an impressive rate of return. Table 3.3 summarizes these achievements.

TABLE 3.3 High-involvement Innovation in German and Austrian Companies

Source: Zentrums Ideenmanagement, 2011.

| Key Characteristics | |

| Ideas/100 workers | 62 |

| Participation rate | 21% |

| Implementation rate (of ideas) | 69% |

| Savings per worker (€) | 622 |

| Investment per worker (€) | 69 |

| Investment to realize each implemented idea (€) | 175 |

| Savings per implemented idea (€) | 1540 |

| Ideas per worker per year | Average of 6, as high as 21 |

For example, survey data from across Europe suggest that the majority of larger organizations have begun its implementation. Another major survey involving over 1000 organizations in a total of seven countries provides a useful map of the take-up and experience with high-involvement innovation in manufacturing. Overall, around 80% of organizations were aware of the concept and its relevance, but its actual implementation, particularly in more developed forms involved, around half of the firms [66]. The average number of years that the firms had been working with high-involvement innovation on a systematic basis was 3.8, supporting the view that this is not a “quick fix” but something to be undertaken as a major strategic commitment. Indeed, those firms that were classified as “CI innovators” – operating well-developed high-involvement systems – had been working on this development for an average of nearly seven years. Research Note 3.6 identifies four enabling factors to support employee-led innovation.

Growing recognition of the potential has moved the management question away from whether or not to try out employee involvement to one of “how to make it happen?” The difficulty is less about getting started than about keeping it going long enough to make a real difference. Many organizations have experience in starting the process – getting an initial surge of ideas and enthusiasm during a “honeymoon” period – and then seeing it gradually ebb away until there is little or no HII activity. A quick “sheep dip” of training plus a bit of enthusiastic arm waving from the managing director isn’t likely to do much in the way of fundamentally changing “the way we do things around here” – the underlying culture – of the organization.

3.5 A Roadmap for the Journey

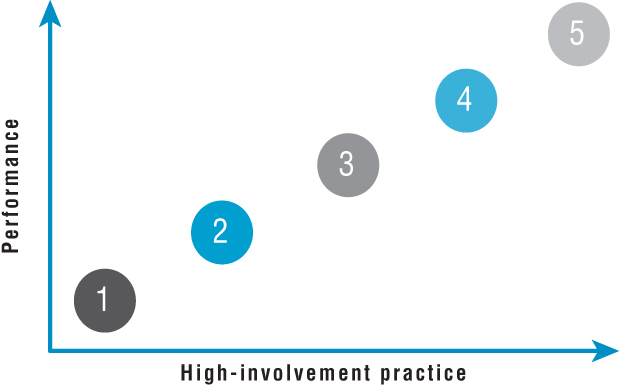

Research on implementing HII suggests that there are a number of stages in this journey, progressing in terms of the development of systems and capability to involve people and also in terms of the bottom-line benefits [22]. Each of these takes time to move through, and there is no guarantee that organizations will progress to the next level. Moving on means having to find ways of overcoming the particular obstacles associated with different stages, as shown in Figure 3.1.

FIGURE 3.1 The five-stage high-involvement innovation model.

The first stage – level 1 – is what we might call “unconscious HII.” There is little, if any, HII activity going on, and when it does happen it is essentially random in nature and occasional in frequency. People do help to solve problems from time to time, but there is no formal attempt to mobilize or build on this activity. Not surprisingly, there is less impact associated with this kind of change.

Level 2 represents an organization’s first serious attempts to mobilize HII. It involves setting up a formal process for finding and solving problems in a structured and systematic way – and training and encouraging people to use it. Supporting this will be some form of reward/recognition arrangement to motivate and encourage continued participation. Ideas will be managed through some form of system for processing and progressing as many as possible and handling those that cannot be implemented. Underpinning the whole setup will be an infrastructure of appropriate mechanisms (teams, task forces, or whatever), facilitators, and some form of steering group to enable HII to take place and to monitor and adjust its operation over time. None of this can happen without top management support and commitment of resources to back that up. In order to maintain progress, there is a need to move to the next level of HII – concerned with strategic focus and systematic improvement.

Level 3 involves coupling the HII habit to the strategic goals of the organization such that all the various local-level improvement activities of teams and individuals can be aligned. Two key behaviors need to be added to the basic suite – those of strategy deployment and of monitoring and measuring. Strategy (or policy) deployment involves communicating the overall strategy of the organization and breaking it down into manageable objectives toward which HII activities in different areas can be targeted. Linked to this is the need to learn to monitor and measure the performance of a process and use this to drive the continuous improvement cycle. Level 3 activity represents the point at which HiII makes a significant impact on the bottom line – for example, in reducing throughput times, scrap rates, excess inventory, and so on. The majority of “success stories” in HII can be found at this level – but it is not the end of the journey.

One of the limits of level 3 HII is that the direction of activity is still largely set by management and within prescribed limits. Activities may take place at different levels, from individuals through small groups to cross-functional teams, but they are still largely responsive and steered externally. The move to level 4 introduces a new element – that of “empowerment” of individuals and groups to experiment and innovate on their own initiative.

Level 5 is a notional end point for the journey – a condition where everyone is fully involved in experimenting and improving things, in sharing knowledge, and in creating an active learning organization. Table 3.4 illustrates the key elements in each stage. In the end, the task is one of building a shared set of values that bind people in the organization together and enable them to participate in its development. As one manager put it in a UK study, “… we never use the word empowerment! You can’t empower people – you can only create the climate and structure in which they will take responsibility…” [46]. Case Study 3.7 provides an example of an organization developing through these different stages.

TABLE 3.4 Stages in the Evolution of HII Capability

| Stage of Development | Typical Characteristics |

| 1. “Natural”/background HII | Problem-solving random |

| No formal efforts or structure | |

| Occasional bursts punctuated by inactivity and nonparticipation | |

| Dominant mode of problem solving is by specialists | |

| Short-term benefits | |

| No strategic impact | |

| 2. Structured HII | Formal attempts to create and sustain HII |

| Use of a formal problem-solving process | |

| Use of participation | |

| Training in basic HII tools | |

| Structured idea management system | |

| Recognition system | |

| Often parallel system to operations | |

| 3. Goal-oriented HII | All of the above, plus formal deployment of strategic goals |

| Monitoring and measurement of HII against these goals | |

| Inline system | |

| 4. Proactive/empowered HII | All of the above, plus responsibility for mechanisms, timing, and so on, devolved to problem-solving unit |

| Internally directed rather than externally directed HII | |

| High levels of experimentation | |

| 5. Full HII capability – the learning organization | HII as the dominant way of life |

| Automatic capture and sharing of learning | |

| Everyone actively involved in innovation process | |

| Incremental and radical innovation |

3.6 Effective Team Working

“It takes five years to develop a new car in this country. Heck, we won World War 2 in four years…” In the late 1980s, Ross Perot’s critical comment on the state of the United States car industry captured some of the frustration with existing ways of designing and building cars. In the years that followed, significant strides were made in reducing the development cycle, with Ford and Chrysler succeeding in dramatically reducing time and improving quality. Much of the advantage was gained through extensive team working; as Lew Varaldi, project manager of Ford’s Team Taurus project put it, “… it’s amazing the dedication and commitment you get from people…we will never go back to the old ways because we know so much about what they can bring to the party…” [67].

Experiments indicate that teams have more to offer than individuals in terms of both fluency of idea generation and in flexibility of solutions developed. Focusing this potential on innovation tasks is the prime driver for the trend toward high levels of team working – in project teams, in cross-functional and inter-organizational problem-solving groups and in cells and work groups where the focus is on incremental, adaptive innovation.

Many use the terms “group” and “team” interchangeably. In general, the word “group” refers to an assemblage of people who may just be near to each other. Groups can be a number of people who are regarded as some sort of unity or are classed together on account of any sort of similarity. For us, a team means a combination of individuals who come together or who have been brought together for a common purpose or goal in their organization. A team is a group that must collaborate in their professional work in some enterprise or on some assignment and share accountability or responsibility for obtaining results. There are a variety of ways to differentiate working groups from teams. One senior executive with whom we have worked described groups as individuals with nothing in common, except a zip/postal code. Teams, however, were characterized by a common vision.

Considerable work has been done on the characteristics of high-performance project teams for innovative tasks, and the main findings are that such teams rarely happen by accident [68]. They result from a combination of selection and investment in team building, allied to clear guidance on their roles and tasks, and a concentration on managing group process as well as task aspects [18]. For example, research within the Ashridge Management College developed a model for “superteams,” which includes components of building and managing the internal team and also its interfaces with the rest of the organization [19].

Holti, Neumann, and Standing provide a useful summary of the key factors involved in developing team working [69]. Although there is considerable current emphasis on team working, we should remember that teams are not always the answer. In particular, there are dangers in putting nominal teams together where unresolved conflicts, personality clashes, lack of effective group processes, and other factors can diminish their effectiveness. Tranfield et al. look at the issue of team working in a number of different contexts and highlight the importance of selecting and building the appropriate team for the task and the context [70].

Teams are increasingly being seen as a mechanism for bridging boundaries within the organization – and indeed, in dealing with inter-organizational issues. Cross-functional teams can bring together the different knowledge sets needed for tasks such as product development or process improvement – but they also represent a forum where often deep-rooted differences in perspectives can be resolved [71]. Lawrence and Lorsch in their pioneering study of differentiation and integration within organizations found that interdepartmental clashes were a major source of friction and contributed much to delays and difficulties in operations. Successful organizations were those which invested in multiple methods for integrating across groups – and the cross-functional team was one of the most valuable resources [49]. But, as we indicated above, building such teams is a major strategic task – they will not happen by accident, and they will require additional efforts to ensure that the implicit conflicts of values and beliefs are resolved effectively.

Self-managed teams working within a defined area of autonomy can be very effective, for example, Honeywell’s defence avionics factory reported a dramatic improvement in on-time delivery – from below 40% in the 1980s to 99% in 1996 – to the implementation of self-managing teams [72]. In the Netherlands, one of the most successful bus companies is Vancom Zuid-Limburg, used self-managing teams to both reduce costs and improve customer satisfaction ratings, and one manager now supervises over 40 drivers, compared to the industry average ratio of 1:8. Drivers are also encouraged to participate in problem finding and problem solving in areas such as maintenance, customer service, and planning [73].

Key elements in effective high-performance team working include:

- clearly defined tasks and objectives

- effective team leadership

- good balance of team roles and match to individual behavioral style

- effective conflict resolution mechanisms within the group

- continuing liaison with external organization.

Teams typically go through four stages of development, popularly known as “forming, storming, norming, and performing [74].” That is, they are put together and then go through a phase of resolving internal differences and conflicts around leadership, objectives, and so on. Emerging from this process is a commitment to shared values and norms governing the way the team will work, and it is only after this stage that teams can move on to effective performance of their task.

Central to team performance is the makeup of the team itself, with good matching between the role requirements of the group and the behavioral preferences of the individuals involved. Belbin’s work has been influential here in providing an approach to team role matching, as discussed in Research Note 3.7. He classifies people into a number of preferred role types – for example, “the plant” (someone who is a source of new ideas), “the resource investigator,” “the shaper,” and the “completer/finisher” (see Research Note 3.7). Research has shown that the most effective teams are those with diversity in background, ability, and behavioral style. In one noted experiment, highly talented but similar people in “Apollo’ teams consistently performed less than the mixed, average groups [20].

With increased emphasis on cross-boundary and dispersed team activity, a series of new challenges are emerging. In the extreme case, a product development team might begin work in London, pass on to their US counterparts later in the day who in turn pass on to their far Eastern colleagues – effectively allowing a 24-hour nonstop development activity. This makes for higher productivity potential – but only if the issues around managing dispersed and virtual teams can be resolved. Similarly, the concept of sharing knowledge across boundaries depends on enabling structures and mechanisms [75].

Many people who have attempted to use groups for problem solving find out that using groups is not always easy, pleasurable, or effective. Table 3.5 summarizes some of the positive and negative aspects of using groups for innovation.

TABLE 3.5 Potential Assets and Liabilities of Using a Group

Source: S. Isaksen and J. Tidd, Meeting the innovation challenge. 2006, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

| Potential Assets of Using a Group | Potential Liabilities of Using a Group |

| Greater availability of knowledge and information | Social pressure toward uniform thought limits contributions and increases conformity |

| More opportunities for cross-fertilization; increasing the likelihood of building and improving upon ideas of others | Group think: groups converge on options, which seem to have greatest agreement, regardless of quality |

| Wider range of experiences and perspectives upon which to draw | Dominant individuals influence and exhibit an unequal amount of impact upon outcomes |

| Participation and involvement in problem solving increases understanding, acceptance, commitment, and ownership of outcomes | Individuals are less accountable in groups allowing groups to make riskier decisions |

| More opportunities for group development; increasing cohesion, communication, and companionship | Conflicting individual biases may cause unproductive levels of competition; leading to “winners” and “losers” |

Research Note 3.8 examines how twelve different team practices contribute to innovation performance for radical projects.

Our own work on high-performance teams suggests, consistent with previous research, a number of characteristics that promote effective teamwork [7]:

- A clear, common, and elevating goal. Having a clear and elevating goal means having understanding, mutual agreement, and identification with respect to the primary task a group faces. Active teamwork toward common goals happens when members of a group share a common vision of the desired future state. Creative teams have clear and common goals. The goals were not only clear and compelling but also open and challenging. Less creative teams have conflicting agendas, different missions, and no agreement on the end result. The tasks for the least creative teams were tightly constrained, considered routine, and were overly structured.

- Results-driven structure. Individuals within high-performing teams feel productive when their efforts take place with a minimum of grief. Open communication, clear coordination of tasks, clear roles and accountabilities, monitoring performance, providing feedback, fact-based judgement, efficiency, and strong impartial management combine to create a results-driven structure.

- Competent team members. Competent teams are composed of capable and conscientious members. Members must possess essential skills and abilities, a strong desire to contribute, be capable of collaborating effectively, and have a sense of responsible idealism. They must have knowledge in the domain surrounding the task (or some other domain that may be relevant) as well as with the process of working together. Creative teams recognize the diverse strengths and talents and use them accordingly.

- Unified commitment. Having a shared commitment relates to the way the individual members of the group respond. Effective teams have an organizational unity: members display mutual support, dedication and faithfulness to the shared purpose and vision, and a productive degree of self-sacrifice to reach organizational goals. Team members enjoy contributing and celebrating their accomplishments.

- Collaborative climate. Productive teamwork does not just happen. It requires a climate that supports cooperation and collaboration. This kind of situation is characterized by mutual trust, in which everyone feels comfortable discussing ideas, offering suggestions, and willing to consider multiple approaches.

- Standards of excellence. Effective teams establish clear standards of excellence. They embrace individual commitment, motivation, self-esteem, individual performance, and constant improvement. Members of teams develop a clear and explicit understanding of the norms upon which they will rely.

- External support and recognition. Team members need resources, rewards, recognition, popularity, and social success. Being liked and admired as individuals and respected for belonging and contributing to a team is often helpful in maintaining the high level of personal energy required for sustained performance. With the increasing use of cross-functional and inter-departmental teams within larger complex organizations, teams must be able to obtain approval and encouragement.

- Principled leadership. Leadership is important for teamwork. Whether it is a formally appointed leader or leadership of the emergent kind, the people who exert influence and encourage the accomplishment of important things usually follow some basic principles. Leaders provide clear guidance, support and encouragement, and keep everyone working together and moving forward. Leaders also work to obtain support and resources from within and outside the group.

- Appropriate use of the team. Teamwork is encouraged when the tasks and situations really call for that kind of activity. Sometimes the team itself must set clear boundaries on when and why it should be deployed. One of the easiest ways to destroy a productive team is to overuse it or use it when it is not appropriate to do so.

- Participation in decision making. One of the best ways to encourage teamwork is to engage the members of the team in the process of identifying the challenges and opportunities for improvement, generating ideas, and transforming ideas into action. Participation in the process of problem solving and decision making actually builds teamwork and improves the likelihood of acceptance and implementation.

- Team spirit. Effective teams know-how to have a good time, release tension, and relax their need for control. The focus at times is on developing friendship, engaging in tasks for mutual pleasure, and recreation. This internal team climate extends beyond the need for a collaborative climate. Creative teams have the ability to work together without major conflicts in personalities. There is a high degree of respect for the contributions of others. Less creative teams are characterized by animosity, jealousy, and political posturing.

- Embracing appropriate change. Teams often face the challenges of organizing and defining tasks. In order for teams to remain productive, they must learn how to make necessary changes to procedures. When there is a fundamental change in how the team must operate, different values and preferences may need to be accommodated.

There are also many challenges to the effective management of teams. We have all seen teams that have “gone wrong.” Research Note 3.9 shows how the dominance of a single cognitive approach to team innovation can be counterproductive. As a team develops, there are certain aspects or guidelines that might be helpful to keep them on track. Hackman has identified a number of themes relevant to those who design, lead, and facilitate teams. In examining a variety of organizational work groups, he found some seemingly small factors that if overlooked in the management of teams will have large implications that tend to destroy the capability of a team to function. These small and often hidden “tripwires” to major problems include [76]:

- Group versus team One of the mistakes that is often made when managing teams is to call the group a team, but to actually treat it as nothing more than a loose collection of individuals. This is similar to making it a team “because I said so.” It is important to be very clear about the underlying goal and reward structure. People are often asked to perform tasks as a team, but then have all evaluation of performance based on an individual level. This situation sends conflicting messages and may negatively affect the team performance.

- Ends versus means Managing the source of authority for groups is a delicate balance. Just how much authority can you assign to the team to work out its own issues and challenges? Those who convene teams often “over manage” them by specifying the results as well as how the team should obtain them. The end, direction, or outer limit constraints ought to be specified, but the means to get there ought to be within the authority and responsibility of the group.

- Structured freedom It is a major mistake to assemble a group of people and merely tell them in general and unclear terms what needs to be accomplished and then let them work out their own details. At times, the belief is that if teams are to be creative, they ought not be given any structure. It turns out that most groups would find a little structure quite enabling, if it were the right kind. Teams generally need a well-defined task. They need to be composed of an appropriately small number to be manageable but large enough to be diverse. They need clear limits as to the team’s authority and responsibility, and they need sufficient freedom to take initiative and make good use of their diversity. It’s about striking the right kind of balance between structure, authority, and boundaries – and freedom, autonomy, and initiative.

- Support structures and systems Often challenging team objectives are set, but the organization fails to provide adequate support in order to make the objectives a reality. In general, high-performing teams need a reward system that recognizes and reinforces excellent team performance. They also need access to good quality and adequate information, as well as training in team-relevant tools and skills. Good team performance is also dependent on having an adequate level of material and financial resources to get the job done. Calling a group a team does not mean that they will automatically obtain all the support needed to accomplish the task.

- Assumed competence Technical skills, domain-relevant expertise, and experience and abilities often explain why someone has been included within a group, but these are rarely the only competencies individuals need for effective team performance. Members will undoubtedly require explicit coaching on skills needed to work well in a team.

Research Note 3.10 reveals some of the challenges of multicultural development teams.

3.7 Creative Climate

“Microsoft’s only factory asset is the human imagination.”

– Bill Gates

Many great inventions came about as the result of lucky accidental discoveries – for example, Velcro fasteners, the adhesive behind “Post-it” notes or the principle of float glass manufacturing. But as Louis Pasteur observed, “chance favours the prepared mind” and we can usefully deploy our understanding of the creative process to help set up the conditions within which such “accidents” can take place.

Two important features of creativity are relevant in doing this. The first is to recognize that creativity is an attribute that everyone possesses – but their preferred style of expressing it varies widely [77]. Some people are comfortable with ideas that challenge the whole way in which the universe works, while others prefer smaller increments of change – ideas about how to improve the jobs they do or their working environment in small incremental steps. (This explains in part why so many “creative” people – artists, composers, scientists – are also seen as “difficult” or living outside the conventions of acceptable behavior.) This has major implications for how we manage creativity within the organization: innovation, as we have seen, involves bringing something new into widespread use, not just inventing it. While the initial flash may require a significant creative leap, much of the rest of the process will involve hundreds of small problem-finding and problem-solving exercises – each of which needs creative input. And though the former may need the skills or inspiration of a particular individual, the latter require the input of many different people over a sustained period of time. Developing the light bulb or the Post-it note or any successful innovation is actually the story of the combined creative endeavours of many individuals. Case Study 3.8 discusses the approach of Google.

Organizational structures are the visible artefacts of what can be termed an innovative culture – one in which innovation can thrive. Culture is a complex concept, but it basically equates to the pattern of shared values, beliefs, and agreed norms that shape the behavior – in other words, it is “the way we do things round here” in any organization. Schein suggests that culture can be understood in terms of three linked levels, with the deepest and most inaccessible being what each individual believes about the world – the “taken for granted” assumptions. These shape individual actions and the collective and socially negotiated version of these behaviors defines the dominant set of norms and values for the group. Finally, behavior in line with these norms creates a set of artefacts – structures, processes, symbols, etc. – which reinforce the pattern [78].

Given this model, it is clear that management cannot directly change culture, but it can intervene at the level of artefacts – by changing structures or processes – and by providing models and reinforcing preferred styles of behavior. Such “culture change” actions are now widely tried in the context of change programs toward total quality management and other models of organization which require more participative culture.

A number of writers have looked at the conditions under which creativity thrives or is suppressed [23]. Kanter [8] provides a list of environmental factors that contribute to stifling innovation; these include:

- dominance of restrictive vertical relationships

- poor lateral communications

- limited tools and resources

- top-down dictates

- formal, restricted vehicles for change

- reinforcement of a culture of inferiority (i.e., innovation always has to come from outside to be any good)

- unfocused innovative activity

- unsupported accounting practices.

The effect of these is to create and reinforce the behavioral norms that inhibit creativity and lead to a culture lacking in innovation. It follows from this that developing an innovative climate is not a simple matter since it consists of a complex web of behaviors and artefacts. And changing this culture is not likely to happen quickly or as a result of single initiatives (such as restructuring or mass training in a new technique).

Instead, building a creative climate involves systematic development of organizational structures, communication policies and procedures, reward and recognition systems, training policy, accounting and measurement systems, and deployment of strategy. Mechanisms for doing so in various different kinds of organizations and in different national cultures are described by a number of authors including Cook and Rickards [24].

Of particular relevance in this area is the design of effective reward systems. Many organizations have reward systems that reflect the performance of repeated tasks rather than encourage the development of new ideas. Progress is associated with “doing things by the book” rather than challenging and changing things. By contrast, innovative organizations look for ways to reward creative behavior and to encourage its emergence. Examples of reward systems include the establishment of a “dual ladder” that enables technologically innovative staff to progress within the organization without the necessity to move across management posts [79].

Research Note 3.11 examines the relative contributions of leadership and culture on new product development success. View 3.1 provides insights on organizational innovation from a leading innovation consultancy.

Climate versus Culture

Climate is defined as the recurring patterns of behavior, attitudes, and feelings that characterize life in the organization. These are the objectively shared perceptions that characterize life within a defined work unit or in the larger organization. Climate is distinct from culture in that it is more observable at a surface level within the organization and more amenable to change and improvement efforts. Culture refers to the deeper and more enduring values, norms, and beliefs within the organization.

The two terms, culture and climate, have been used interchangeably by many writers, researchers, and practitioners. We have found that the following distinctions may help those who are concerned with effecting change and transformation in organizations:

- Different levels of analysis. Culture is a rather broad and inclusive concept. Climate can be seen as falling under the more general concept of culture. If your aim is to understand culture, then you need to look at the entire organization as a unit of analysis. If your focus is on climate, then you can use individuals and their shared perceptions of groups, divisions, or other levels of analysis. Climate is recursive or scalable.

- Different disciplines are involved. Culture is within the domain of anthropology and climate falls within the domain of social psychology. The fact that the concepts come from different disciplines means that different methods and tools are used to study them.