Speculative financial instruments – derivatives

Overview of derivatives markets

OVERVIEW OF DERIVATIVES MARKETS

So far we have discussed the financial instruments used mainly for borrowing and investment of principal both short term (money market) and long term (capital market). Those securities appear on clients’ and banks’ balance sheets and can ‘block up’ the credit lines. Most market participants have exposure limits in each product sector and once those are exhausted no further funds can be utilised. To overcome this problem they can trade ‘off-balance sheet’ instruments that do not involve exchange of principal, more commonly known as derivative securities. These financial instruments derive their value from the underlying asset, hence the term derivative. There is a wide range of products available for trading, both at listed exchanges and OTC. The exchange-traded products provide protection against counterparty default, but trading is only open to the exchange members. Furthermore, the contract specifications are exact and the product range is limited. There are over 40 recognised derivatives exchanges worldwide, the most popular ones are listed in Table 5.1. Some exchanges are physical, where transactions are executed openly on the exchange floor, whilst still providing electronic trading after hours. On the other hand, some exchanges are purely electronic, such as LIFFE and NASDAQ, providing a virtual derivatives market.

Table 5.1 Most popular worldwide derivatives exchanges

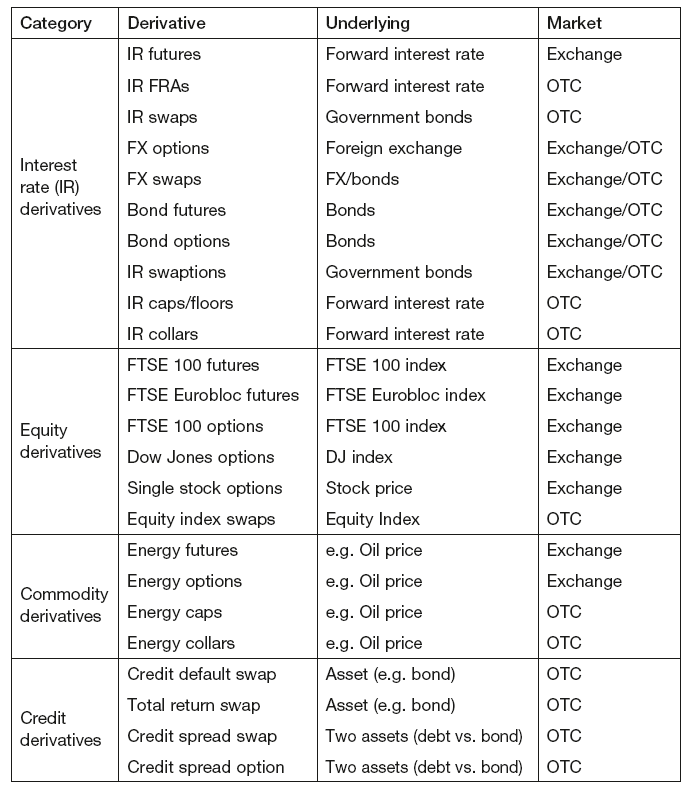

The product range offered by each exchange varies, and some of the most common are listed in Table 5.2, together with their OTC counterparts.

Table 5.2 Most popular exchange-traded and OTC securities

Due to the limitations imposed by exchanges (product range, strict specifications, market participation), the OTC market is growing rapidly. The investment banks are devising new product structures and investment strategies daily to meet exact client specifications. However, each buyer and seller must take on the credit risk of their counterparty.

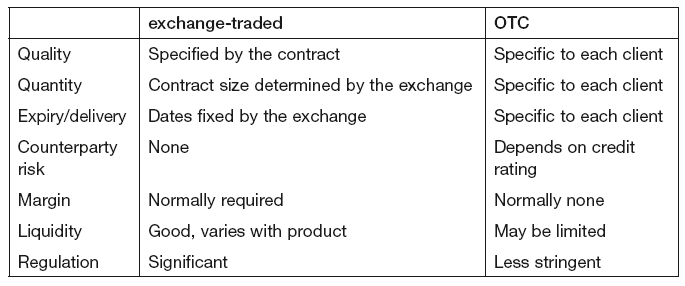

The main characteristics of exchange-traded vs. OTC derivatives are listed in Table 5.3. Both exchange-traded and OTC derivative instruments can be split by settlement into two categories: single vs. multiple settlement. Some examples are listed in Table 5.4. They can also be split by premium requirements. Instruments which are obligations to enter into a contract at some future date cannot be abandoned, and hence require no premium. On the other hand, the securities that give a client the right but not the obligation to take action in the future will require the premium to be paid up-front. Hence, it can be summarised that the optionality has to be paid for, as it provides a worst-case scenario to the buyer; whilst the obligation does not incur such a cost.

Table 5.3 The main characteristics of exchange-traded vs. OTC derivatives

Table 5.4 Examples of single and multiple settlement derivatives securities

| Single settlement | Multiple settlements |

|---|---|

| Interest rate options | Interest rate swaps |

| Currency options | Currency swaps |

| Financial futures/FRAs | Energy swaps |

| Stock options | Interest rate caps/floors/collars |

Whether exchange-traded or OTC, derivatives offer greater exposure to the fluctuations of the underlying security compared to owning it outright. If a client purchases an option to buy a stock with the strike of £100 and pays £10 in premium; if the price increases to £120, he has made a profit of £10, 100 per cent of the original investment. If he owned the stock, he would only earn 20 per cent of his original investment. However, should the price fall to £90, the option holder will lose 100 per cent of his premium, whilst the stock holder will lose only 10 per cent of the original value. This loss is called ‘gearing’ and is the driver behind derivatives trades. Most market participants enter into transactions with the intention of earning a profit. Whilst derivatives offer greater potential, they can also incur significant losses when the market moves adversely. Therefore, derivative instruments should be traded prudently. The different motivations behind the trades are discussed in the following section.

USERS OF DERIVATIVES

There are different types of derivatives users:

Traders make a market in derivatives by creating various products and selling them to their clients.

Hedgers wish to protect themselves against exposure to adverse market movements.

Speculators take positions in derivatives based on their view of a particular market.

Arbitrageurs try to spot price discrepancies and profit from them.

The derivatives market is mainly populated by:

- Supranationals

- Governments and their agencies

- Investment banks

- Financial institutions

- Corporates

- Private clients.

Their motivation for using derivatives is varied, some examples are:

- Protecting a portfolio of stocks against devaluation

- Profit from increase of oil price

- Protection against interest rate increase on a loan

- Securing an FX rate on a future transaction

- Enhancing a yield of a portfolio

- Protection against payment default.

Each of the above requires a different type of derivative instrument. They are briefly covered below and further discussed in the following chapters.

INTEREST RATE DERIVATIVES

Interest rate derivatives derive their value from the movements in the underlying interest rate. As there is no principal involved, the difference between the market rate and that implied by the contract is settled between the counterparties. Hence they can be used to fix the borrowing rate for some future transaction (by buying a futures contract, or a call option), change payments from floating rate to fixed (by entering into a ‘vanilla’ swap), change frequency and reference rate of payments (basis swap), secure FX rate for a foreign business contract (currency option or future) etc.

There is a wide range of interest rate derivatives, some are exchange-traded, but the largest volume and variety exists in the OTC market. They can be classified in variety of ways:

- By maturity

- By settlement

- By complexity.

Derivative securities maturities range from overnight to over 30 years. Table 5.5 shows the terminology used when referring to derivatives of different types.

Table 5.5 Types of interest rate derivative securities by maturity

| Maturity (years) | Instrument type |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | Money (cash) market |

| 1–2 | Short-term instruments |

| 2–5 | Medium-term instruments |

| 5–10 | Long-term instruments |

| 10+ | Very long-term instruments |

Further division of derivative securities can be done by the type of settlement. Whilst some have only a single settlement date (and consequently one exchange of cashflows), some derivatives have multiple fixings (comparisons against the pre-agreed benchmark). In general, the number of fixings (and hence payments) is related to the maturity of the instrument – longer-dated securities typically having multiple settlement dates. Table 5.6 shows some examples of single- and multiple-fixing types of derivative securities:

Table 5.6 Types of interest rate derivative securities by settlement type

| Settlement | |

|---|---|

| Single | Multiple |

| Financial futures | Interest rate swaps |

| Forward rate agreements (FRAs) | Interest rate caps |

| Interest rate swap options | Interest rate floors |

| Interest rate options | Interest rate collars |

The choice of derivative security the investor will make depends on many factors:

- Risk aversity

- Understanding of derivatives risks and exposures etc.

- Size of investment

- Market accessibility

- Period of exposure

- Type of exposure.

Clients with substantial knowledge on derivatives products, their valuation principles, market and credit risk are typically more willing to accept greater risks as they feel that they have better understanding of those risks and can manage them better.

Market accessibility and the size of investment are also crucial drivers in the derivatives investment choice. For example, exchange trading is open only to its members and the trading is allowed only in whole numbers of contracts of fixed size and tenor.

Period and type of exposure are still the main factors influencing the investment decisions. Most derivative securities offer only a limited range of maturities, or better liquidity for certain tenors. Furthermore, the underlying exposure limits the number of instruments suitable for investment. In other words, long-term borrowing cannot be suitably hedged by buying a strip of futures or FRAs; equally, overnight borrowing cannot be fixed by entering into a swap.

Table 5.7 offers an indication of the type of instruments the investors typically use, depending on the exposure period. A full range of interest rate derivatives is covered in Chapters 6, 7 and 9, with further coverage of OTC exotic derivatives in Chapter 12.

Table 5.7 Interest rate derivative products by exposure periods

| Maturity (years) | Instrument type |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | Futures, FRAs, options, caps, floors, collars |

| 1–2 | Futures, FRAs, options, caps, floors, collars, swaps, swaptions |

| 2–5 | Caps, floors, collars, swaps, swaptions |

| 5–10 | Caps, floors, collars, swaps |

| 10+ | Swaps |

EQUITY DERIVATIVES

Value of equity derivatives is based on, or derived from, the value of the underlying equity, equity index or a basket of stocks. A client who finds it prohibitively expensive or impractical to buy stocks can enter into an equity swap, whereby he/she receives return on an equity index and pays a variable interest rate. Or a portfolio manager who would like some protection against a fall in stock prices would buy an equity put option. Holders of individual stocks can also transact in options, depending on their view of price movements, in order to realise potential profit without having to sell the stocks at the outset.

It can be seen from the above that the main motivations for trading equity derivatives are as follows:

- Equity market speculation

- Enhancement or hedging of the equity portfolio returns

- Gaining access to equity market.

Speculators often take only a very short-term view, aiming to realise profit by reversing the original transaction well before the maturity date. Hence their choice of product will mainly be driven by their view of the short-term market trends.

On the other hand, portfolio managers base their decisions on several factors, including:

- Portfolio structure

- Portfolio size

- Risk aversity

- Period of cover.

The manager of a relatively static portfolio would greatly benefit from short- to medium-term derivative securities with single, more volatile stocks as the underlying. However, pension and fund managers often aim to track and outperform the equity index, hence they are more risk-averse and require long-term exposure.

Finally, investors without direct exposure to equity markets will base their instrument choice on:

- Type of desired exposure

- Type of underlying exposure in a different market

- Size of investment

- Risk aversity

- Understanding of the equity derivatives market and associated risks and exposures.

They typically aim to swap existing exposure in one market (e.g. interest rate) to equity returns. Hence their product choice is driven by their risk aversity (typically linked to their understanding of the equities market), underlying exposure (single vs. multiple settlement) and exposure period. Examples of equity derivative products classified by the exposure period (maturity) are given in Table 5.8. Equity derivatives are covered in Chapter 10.

Table 5.8 Examples of equity derivative products classified by the maturity

| Maturity (years) | Instrument type |

|---|---|

| 0–2 | Equity index futures, equity index options, single stock options |

| 2–5 | Equity index swaps, equity index swaptions |

| 5+ | Equity index swaps |

COMMODITY DERIVATIVES

As there are many commodities traded in the world markets, so are many derivatives products. But the most commonly traded ones are energy derivatives, as the price of energy impacts on so many sectors. A manufacturer that uses large quantities of oil, instead of buying it now to secure the price and having to pay for storage, can enter into a call option contract or a futures contract and achieve the same effect more efficiently. An energy company that fears the fall in prices would enter into an opposite transaction.

The types of available trading strategies are a clear indication of how the market participation in commodities sector has changed over the years. At present there are three types of energy markets:

- The spot or physical market

- The forward market

- The energy futures market.

The spot market is used for direct delivery of cargo, hence its participants are typically large corporations with extensive energy consumption.

The forward market is an informal, short-term market mainly populated by speculators, with contract volumes far exceeding the actual production, and contracts changing hands several times before the actual delivery. Thus only a small percentage of participants are the actual energy users and producers.

Finally, the official energy futures markets typically offer a limited number of a short-term contracts and are mainly populated by the investors, rather than actual energy users or producers.

For more exotic products and longer-term exposure, the investors have to turn to the OTC equity market. The most popular OTC equity derivatives are swaps, but the range of products can be extended to meet exact client specifications. Commodity derivatives are covered in Chapter 11.

CREDIT DERIVATIVES

Credit derivatives are currently traded in OTC markets only (even though some credit derivative features can be imbedded into money markets products). They are contracts that allow one counterparty to accept – in exchange for a premium – a reference asset credit risk from another counterparty (who does not have to own the asset). The counterparties are respectively referred to as credit protection seller and credit protection buyer. The use of credit derivatives is widespread, as there are many types of reference assets (e.g. bond, loan or equity) as well as types of credit risk (credit rating downgrade, bankruptcy, failure to pay etc.).

The contracts can be bilateral, whereby the two counterparties swap all or a part of reference credit exposure for mutual benefit. This is typically done to diversify market exposure without actually investing in a range of assets.

But more commonly, credit derivatives are traded as separate securities, by stripping the credit risks on the underlying asset from the asset itself. Similar to other derivatives markets, the users of credit derivatives are broadly split into hedgers and speculators:

Hedgers typically become protection buyers when they own the reference asset and wish to eliminate risks associated with adverse credit events.

Speculators can be both protection buyers and sellers, depending on their view of the market.

As the credit derivatives market is OTC, each trade is tailor-made to fit the exact client needs. Therefore the classification by market accessibility, contract size, maturity etc. does not apply. Furthermore, the payments are contingent on credit events, the timing of which is impossible to predict. Credit derivatives are covered in Chapter 11.