Chapter 10

Food Calendars

Chart what you eat and where it comes from.

CREDIT: Thanks to Peg Vamosy for this photo of Mana Joana and her students harvesting rice in the Aileu district.

In the United States every school child knows that milk comes from the supermarket, and in fact food in general comes from a box, bag, or can. Fresh fruits and vegetables are also available; heck, most of them are available consistently, month after month, year-round. They’ve got tiny little tags that tell you grudgingly where they’re from, but who cares? Pass the celery! That all this life-giving food was produced on a specific patch of earth somewhere is a fact lost on a great many children, and even adults.

In Timor most people know where the majority of their food is produced. Not only do subsistence farmers know that it comes from the earth, they also know which patch of earth produced each calorie, in what month, and with what additional inputs of labor and material. Just as young American kids learn their shapes and colors as toddlers, farmer kids in Timor learn about their food.

This is no mystery. Food is one of the key elements of life, like air and water, and when it is hard to find, life becomes no fun at all. In the United States, industrial food systems have made it seem like food is a sure thing, a permanent fixture on the supermarket shelves, polished and perfect, packaged for long life and easy transport. Even if you run out of food in your house, you know it’s not because there is none in the store down the street.

Doing this activity will be a challenge if you’re not living in the Majority World, but it should give you a good new perspective on how you feed yourself. The reason we teach the food calendar here is because there are still sections of the year in most of Timor-Leste when not much is coming ripe from field or forest. Some things are available year-round, such as bananas and papayas (these can be used as vegetables as well as fruits), and meat and fish have no particular season. Still, there are times of the year in many locations referred to as the “hungry season.” Government and local organizations are working to help farmers look at all options to fill in the sparse parts of the calendar with crops that will create a welcome harvest during those times.

If you don’t have the problem of a hungry season, then you chose your parents well, and the industrial food system is keeping you satisfied, at least temporarily. But take this chance to consider many in the Majority World who understand, as we all really should, how much we depend on the very soil beneath our feet.

Tinker

Write down the 10 meals or snacks you eat most, day by day or week by week. Don’t write down individual foods, but rather the main foods of a meal, or the main group of food for common snacks. We’ll keep this simple by ignoring drinks. Here’s a hypothetical list that could be the diet of my niece, living near Kansas City, Missouri:

- Hamburgers with fries

- Spaghetti

- Sandwiches

- Cereal

- Burritos

- Chips, crackers, and cookies

- Apples, oranges, and bananas

- Pizza

- Pancakes

- Donuts and pastries

Now see if you can dissect those foods into their elemental ingredients. Don’t worry about the small stuff like sugar, salt, spices, and oil, but try to get all the major foodstuffs. For example:

- Hamburgers

- Wheat (bun)

- Beef

- Cucumbers (pickles)

- Potatoes (fries)

- Spaghetti

- Wheat (pasta)

- Tomatoes, canned (sauce)

- Beef (sauce)

- Garlic (sauce)

- Mushrooms (sauce)

- Sandwiches

- Wheat (bread)

- Peanuts (peanut butter)

- Strawberries (jam)

- Cereal

- Corn (grain, not sweet corn)

- Milk

- Burritos

- Wheat (tortilla)

- Beans

- Chicken

- Rice

- Lettuce

- Tomato, fresh

- Onions

- Chips, crackers, and cookies

- Potatoes

- Corn (grain, not sweet corn)

- Wheat

- Apples, oranges, and bananas: no mystery here

- Pizza

- Wheat (crust)

- Tomatoes, canned (sauce)

- Beef (pepperoni)

- Pancakes

- Wheat

- Eggs

- Milk

- Donuts and pastries: Wheat

Now regroup the elemental ingredients into a big table, each one listed only once, and separated roughly into categories. On the right, leave space for the 12 months of a year:

J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | ||

| Meat, dairy, and eggs | Chicken | ||||||||||||

| Beef | |||||||||||||

| Milk | |||||||||||||

| Grain and other starch | Corn (grain, not sweet corn) | ||||||||||||

| Wheat | |||||||||||||

| Rice | |||||||||||||

| Potatoes (frozen) | |||||||||||||

| Veggies and legumes | Lettuce | ||||||||||||

| Tomato, canned | |||||||||||||

| Tomato, fresh | |||||||||||||

| Onions | |||||||||||||

| Cucumbers | |||||||||||||

| Mushrooms | |||||||||||||

| Beans | |||||||||||||

| Garlic | |||||||||||||

| Fruit | Apples | ||||||||||||

| Oranges | |||||||||||||

| Bananas | |||||||||||||

| Strawberries |

Tomatoes appear twice because they were fresh on the burger and canned and processed in the spaghetti sauce. This differentiation will help later on.

Now that we have most of our main foods in the calendar, we’ll mark it up get a better perspective on what we’re eating. Here is the gist of the system we’ll use:

- Green = fresh food that may have been grown locally

- Blue = food that was preserved (frozen, canned, processed)

- Orange = fresh food that was definitely shipped in from far away

- X = harvest season for a given food, meaning it could have come straight to your table from the farm

Follow me closely, doing it for your home, whereas I’ll be doing it as if for my niece in the Kansas City area. You can check the marking for each step on the final calendar later in the chapter.

Put an X on months for harvest seasons on those items that could have been produced within a 100-mile (150-km) radius of your home. This is sort of arbitrary, but it gives us a baseline to work with. This is a tricky part for those of us no longer connected to the land. You may have to ask someone you know with a garden, look up harvest calendars in the library or online, or make your best guess. Put an X on the months when each of these foods would come ripe or ready, if they were produced where you are.

Before we go on, we have to accept that just because these foods were ripe locally doesn’t mean that the ones you ate were actually the local ones. That’s the way our convoluted, industrially opaque food system works now. In California, we live just up the road from Castroville, the artichoke capital of the nation, yet routinely see artichokes from Spain for sale in local stores. My friends were biking through the colossal wheat fields of Kansas, yet in the small-town mom-and-pop shops they stopped in for supplies there was nothing but corporate white bread shipped in from hundreds of miles away. That happens all the time. It’s a good reason to find out more about what you’re eating and where it came from.

Anyhow, these Xs represent a possibility: that this food could be found fresh in that month where you are.

We’re already starting to notice a distinct pattern in the calendar. It’s clear that animals can be milked or slaughtered any time of the year, but most crops only grow well in the summer throughout most of the temperate region, and take weeks or months to get to harvest readiness.

Now, for foods that are not grown locally where you are, mark the whole row orange, but not the food’s name.

After that, highlight food names in green for each food that you ate fresh or stored/preserved naturally (dried, kept in cellar) and not canned, frozen, or otherwise processed. By processed I mean it was altered in some significant way. For example, wheat was made into flour, but all the original stuff is there (in the case of whole wheat). Rice was hulled and maybe polished, but you’re still getting the real stuff. These both count as fresh—mark them green. The potatoes that made your fries were frozen and the milk was homogenized and jugged, so that counts as not fresh, as does the frozen meat. If you had freshly slaughtered meat and chopped up fresh potatoes for your fries, put ’em in green.

How much green have you got? That’s a big distinction right there. Here in Timor, many people’s calendars will be nearly 100 percent green. Exceptions will be canned fish and other meat, and instant noodles. Most Timorese simply do not think of the supermarket when they think of food. They think of their fields and gardens.

Before the next step, we need to talk about storing and preserving food. Just by looking at the Xs on the calendar, you can see the problem. It’s the same problem faced by our great-grandparents 150 years ago all the way back to our ancestors 6,000 years ago when agriculture was just starting up: What’s to go with the meat for supper when those other crops are not ripe yet? In other words, how to preserve these crops so that we can eat them for months after they’ve been harvested? Canning and freezing are modern ways, and a range of ancient ways, such as drying, salting, pickling, and cellar storage, are still used today.

Here we’ll make a distinction between the more modern, processed methods of freezing, canning and packaging (with blue), and the old ways (with green).

Highlight names and entire rows in blue for those that you ate preserved (frozen, canned, or processed). If the row is already orange, meaning it came from afar, leave it. This blue distinction is made according to how the food is manipulated before it gets to you, but you’re also often hard-pressed to know where these were produced. Some may have been local, but others came from outside the country, maybe the other hemisphere.

Highlight all squares with Xs that are not blue or green, and also highlight in green the squares for the months that these items would last if stored/preserved naturally.

You can see a few foods are made to last: grains dried will last the year, and many root crops as well as some fruit will keep for months in cool areas. Other wimpy veggies like lettuce last only days once harvested, even with refrigeration.

Highlight all remaining squares in orange, meaning these were definitely shipped from afar if you ate this stuff during this month.

There’s your food calendar!

J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | ||

| Meat, dairy, and eggs | Chicken | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Beef | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Milk | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Grain and other starch | Corn (grain, not sweet corn) | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Wheat | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Rice | |||||||||||||

| Potatoes (frozen) | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Veggies and legumes | Lettuce | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Tomato, canned | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Tomato, fresh | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Onions | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Cucumbers | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Mushrooms | |||||||||||||

| Beans | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Garlic | X | X | |||||||||||

| Fruit | Apples | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Oranges | |||||||||||||

| Bananas | |||||||||||||

| Strawberries | X | X | X | X |

Here’s the list and calendar for our family, mostly vegetarian, here in Timor-Leste.

- Rice, beans, tempeh, tofu, and vegetables

- Pasta with sauce and cheese

- Fish and chips (fries)

- Pizza (homemade)

- Oatmeal and once-a-week cold cereal

- Toast with butter and jam or honey

- Cheese sandwiches

- Banana chips, peanuts, crackers

- Fruit, mostly local

- Salads

Here’s our calendar:

| Meat, dairy, and eggs | Fish | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Milk | |||||||||||||

| Eggs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Grain and other starch | Rice | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Oatmeal | |||||||||||||

| Wheat | |||||||||||||

| Veggies and legumes | Kanko (water spinach) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Carrots | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Lettuce | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Mustard greens | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Eggplant | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Tomatoes, fresh | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Tomatoes, canned | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cucumbers | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Garlic | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Onions | X |

X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Pinto beans | X | X |

X | X | X | ||||||||

| Peanuts (PB) | X | X | X |

X | X | ||||||||

| Potatoes | X | X |

X | X | X | ||||||||

| Fruit | Avocados | X | X | X | X | X |

X | X | |||||

| Banana | X | X | X | X | X |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Passion fruit | X | X | X | X | X |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Papaya | X | X | X | X | X |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Strawberries (jam) | X | X | X | X |

Check out all those Xs! All that green! Welcome to the tropics! I’ve labeled green anything that’s produced on this small half-island, calling it all local. A couple of small operations are producing jam from the high-mountain strawberry operations, and I’m here to tell you, they know what they’re doing.

You can see that if we could break our wheat, oat, and milk habits, we’d be pretty much eating all local. Of course we eat other stuff: jams and fruit juices and junk food treats mostly from Indonesia, but our main sustenance is represented in the calendar.

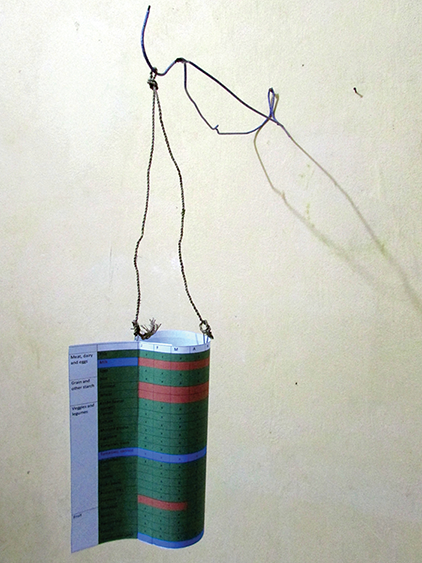

Here is our calendar cut out and formed into a hanging spinner mounted on a bent hanger nailed to the wall. It drifts around, a bit like the earth and the seasons, to remind us about the sources of our food.

What’s Going On?

Let’s go over the meaning of these markers again:

- Green: Fresh, and produced locally so you may be eating fresh local (though not at all a sure thing)

- Green X: Could be straight from a nearby field

- Blue: Preserved, and who knows where it’s from

- Blue X: Missed opportunity—those months you could have eaten this item fresh local, but chose the preserved, probably shipped in

- Orange: Either shipped in from afar or produced in a greenhouse for sure

Greenhouses, by the way, can function as a local, ecological option to lengthen the season of fresh produce. The greenhouse effect can keep the temperature up so that various vegetables can grow inside when they would die outside. On the downside, some places also burn petroleum to heat greenhouses and produce things like tomatoes when it’s snowing outside. So you may hesitate before indulging in those hothouse tomatoes when you’re wearing four layers. If they seem a bit expensive, it’s probably due to the massive heat loss through the thin walls and roofs of the greenhouse.

The main modern method of accessing “fresh” out-of-season foods is shipping them in from a place where they are in season. A lot of crops like lettuce and tomatoes can be grown across the southern strip of the United States pretty much any time of year with enough irrigation, and the pear season in Chile just happens to be the dead of the Minnesota winter. If the shipping can be carried out quickly enough, we still get fresh food in the supermarket. Of course, agro-industry will do anything to keep that food looking fresh longer, including dumping chemicals on it and breeding it in ways that deprioritize taste, so let the buyer beware. And of course all that transport has serious ramifications for climate change. So it’s good to stay a bit skeptical when you see fabulous stuff in your supermarket out of season in the fresh section. Local fresh food is really the only fresh fresh food.

One weakness of our calendar is that it assumes you eat more or less the same meals year-round. You may not, and your ancestors surely didn’t, and Timorese don’t either. Folks here were and are mostly dependent on the growing and gathering seasons of their climate.

The key to sustainability is eating local stuff. You want to maximize green in your calendar and make sure blue items are produced locally. The extent to which you can do this will depend on your flexibility and the diversity of agriculture where you are. You will need to eat more with the seasons, like your dear great-great-grandparents did. Ironically, if you are keen to eat more local foods, one of the key solutions is to rely on foods preserved with both older and modern methods. You could do canning yourself, or buy a large freezer for garden excess. But you can also find and patronize local businesses that preserve local food.

Where is the most orange? In the Kansas City calendar shown here, it’s in April and May. Those were the hungry months of our temperate climate ancestors: birds singing, meadows in bloom, crops bursting forth from the soil, but not…yet…ripe. So temperate climate peoples through the ages have had to wait and continue eating the half-moldy stuff in the cellar from last year’s harvest.

You can imagine the extraordinary amplification of appreciation when the first vegetables came ripe after a period of waiting—the first tender peas to fill out their pods, the first crisp radishes to redden, the first berries from the vine. Mmmm, it makes my mouth water just fantasizing about that moment.

Aside from being pleasurable, eating with the seasons spares the world the waste of transport emissions and supports local farmers. It may be interesting for you to try eating nothing but local for a time—one week, one month. Barbara Kingsolver tried it for a year, as you can read in her book Animal, Vegetable, Miracle. Permaculture’s magazine and website are inspiring. And just strolling into some dirt and planting something is like a trip to the ancient past; the essence of our existence as an agricultural society comes down to seeds growing in soil to produce something that will sustain us. Folks here in Timor don’t have any doubt about that.