The Web offers you a combination library, entertainment center, and social club—none of which ever closes. Your Web browser is your window into this busy world. This chapter explains how to choose between the two most popular browsers, Internet Explorer and Firefox, as well as how to set them both up, navigate between Web sites, and get the most out of their many frills. You’ll also learn how to pinpoint which sites contain the information you need, and then how to print, save, or forward pages from the sites you visit. And since most sites nowadays force you to create a user account and password, you’ll learn some timesaving tricks to cut down on your digital form-filling chores.

All browsers, including Internet Explorer and Firefox, can handle the basics, helping you move from site to site. But just as some cars include drink holders and extra suspension, some browsers offer extra features that smooth out your ride from one site to another. The differences lie mainly in how they manage tasks like these:

Compatibility. Web pages are written in a special programming language (called HTML, or hypertext markup language, if you’re interested in that sort of stuff); it’s basically a series of code words that browsers read in order to display a page’s contents. All Web pages and browsers speak the same language when it comes to the basics—putting words and images onto a page. But some support special dialects; others don’t. That’s why some Web pages look and behave better in one browser than in another. This usually isn’t an issue, but occasionally you’ll find a site with features that display and work in one browser, but not in another.

Pop-up blocking. Pop-up ads are advertising-filled windows that pop into your face like irritating gnats, usually when you first visit or attempt to leave a site. The worst sites send flurries of pop-up ads. Simply blocking all pop-ups won’t work, because some of these windows actually do good things, like present you with a map or some other nugget of helpful info. To weed out the good from the bad, some browsers let you manage pop-ups, permitting a few sites to present them and banishing them from all others.

Ad blocking. Free sites need to recoup their costs somehow; most Web surfers have therefore gotten accustomed to viewing a few text ads along the side of a page. But the most irritating ads squat in the middle of your reading material, flashing distracting mini-movies as you try to concentrate on the site’s content. A browser’s ad-blocking features let you manage ads, banishing the most obnoxious ones, while leaving alone unobtrusive ones that may interest you.

Security. Today’s Web browsers must double as security guards, alerting you when deceptive sites try to install unwanted software on your PC, or when something’s fishy about an online shopping site. For instance, some sites try to install spyware—software that nosey sites (and ad delivery companies) sneak onto your PC to monitor your Web-browsing habits. If the spyware notices that you visit lots of bowling sites, for instance, it might start showing you bowling ads—sometimes even displaying them on your monitor when your browser isn’t running. Good browsers help you stay on top of what’s being installed and let you decide what gets on your PC and what gets stopped.

Add-ons. People need a Web browser that works the way they do. Add-on programs called extensions subtly add new capabilities to your browser. Helpful add-ons can, for example, notify you of incoming email or upcoming storms. Malicious add-ons, sneakily applied by shady Web sites, can damage your PC. That’s why a browser needs an add-on manager for deleting the bad and keeping the good.

Backups. Tweaking a Web browser’s settings to work the way you want takes considerable time. A browser should let people save its settings for backup or for moving to another PC or laptop.

The following sections describe the two main browsers on the market: Windows XP’s built-in Internet Explorer, and the Mozilla Foundation’s increasingly popular Firefox.

Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (Start → All Programs → Internet Explorer) attracts big crowds for three main reasons: it’s free, it works pretty well with the majority of sites out there, and it’s already installed on your PC. The current version, Internet Explorer 6.0 (shown in Figure 13-1), arrived with Windows XP.

Figure 13-1. When Microsoft added Internet Explorer to new editions of Windows in the mid-90s, people gradually stopped downloading Netscape, the most popular browser at the time, and switched to their PC’s new preinstalled freebie. (This led to the dethroning of Netscape as browser king, antitrust investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice, a lawsuit from 20 states, and Microsoft’s ultimate settlement with the Department of Justice—a story whose details would require a much-thicker book.) Today, Internet Explorer needs updating. Its search box (shown here), for instance, blocks the view of the site you’re trying to search.

Windows XP’s Service Pack 2 (Section 15.4) added several crucial security features to Internet Explorer, including an add-ons manager (Tools → Manage Add-ons) for disabling some types of spyware, and other unwanted programs that latch onto Internet Explorer. A much-needed pop-up blocker (Tools → Pop-up Blocker → Turn On Pop-up Blocker) now stops the most annoying pop-up windows.

Internet Explorer is free and provides enough basic Web-browsing tools to capture about 85 percent of the browser market. It’s also the only browser supporting ActiveX, a proprietary Microsoft technology that lets Web sites install and run programs—some helpful, some malicious—on your PC. Some Web sites that scan your PC for viruses, for instance, ask you to first download an ActiveX program.

Being the top dog for so many years, Internet Explorer remains the prime target for viruses and spyware, many of which install themselves through ActiveX programming tools. Microsoft has also let the program fall behind in development. Competing browsers like Firefox run more securely and offer more features.

Since Internet Explorer comes bundled with Windows XP, you don’t need to install it or set it up. To start Internet Explorer, choose Start → All Programs → Internet Explorer. If you don’t spot Internet Explorer on the menu, thank the long arm of the law—as part of Microsoft’s antitrust settlement with the Department of Justice, Microsoft added an option to drop Internet Explorer from Windows XP’s menus. If you’re not finding Internet Explorer anywhere on your PC, check out the box on Section 13.1.1.4 for instructions on how to put it back.

Internet Explorer lets you back up your Favorites—your list of shortcuts to frequently visited Web sites. This list of your Favorites is a handy thing to back up to a portable USB drive (Section 9.2), since doing so lets you visit your favorite sites from any PC (see the tip below). Internet Explorer also lets you back up your cookies, tiny Web site preference files (see the “Taking Cookies Off the Plate” box for the full story on what cookies are and how they work). Backing up your cookies lets you copy them to another computer, so that Web sites recognize who you are when you’re visiting from, say, your laptop rather than your desktop PC.

To back up either your Favorites or your cookies (or both), choose File → Import and Export to summon the Import/Export wizard. This terse wizard lets you export your Favorites to a file called Bookmark.htm and your Cookies to a file called Cookies.txt, and then places both files in your My Documents folder.

To transfer the bookmarks or cookies to Internet Explorer on another PC, copy those small files to a floppy disk, USB drive, or networked folder (Section 14.8.5). Then, while at the other PC, open Internet Explorer and use the same Import/Export wizard. This time, though, choose Import and point the wizard to the folder containing your exported files.

Tip

Internet Explorer actually exports your Favorites in the form of a ready-to-view Web page. If you’ve copied the Bookmark.htm file to a USB drive and want to view those shortcuts on another PC, all you have to do is insert the drive in the PC you’re visiting, double-click the drive’s Bookmark.htm file, and, presto, that PC’s browser presents your Favorites as a Web page, all listed in a row of clickable links.

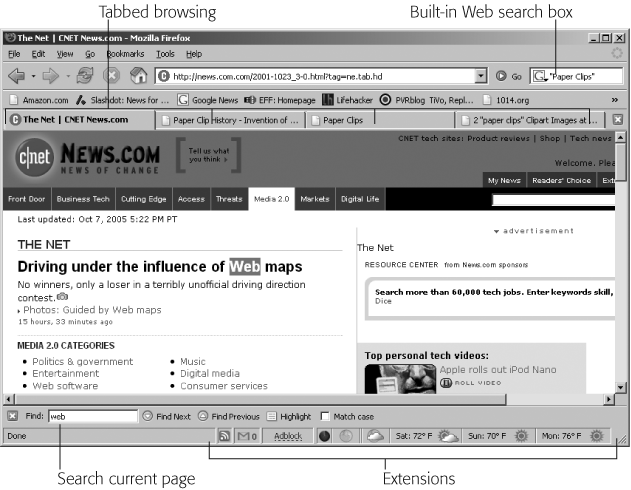

Millions of people have downloaded Firefox, shown in Figure 13-2—enough, in fact, to capture about 10 percent of the browser market. That’s a serious chunk, considering that Firefox entered the market only about a year ago. The fast-growing browser’s threat prodded Microsoft to announce Internet Explorer 7, which incorporates many of the features Firefox has. (Internet Explorer 7 will be released with Windows next generation operating system—Vista—in late 2006.)

Firefox offers all the basics of Internet Explorer, and then tacks on a few of its own innovations.

Tabbed browsing. To open a second Web page in Internet Explorer, you need to open up a separate window. Consequently, it’s not uncommon to have a half-dozen Internet Explorer windows cluttering a desktop. Firefox, by contrast, places several Web pages in the same window, placing a little tab atop each page. Click the tab, and Firefox switches its view to that site. You can even open several links simultaneously, letting them load in the background while you read the first page.

Security. Firefox doesn’t support ActiveX controls (Section 9.4), effectively thwarting the most common point of entry for spyware. Tests consistently rank the program as more secure than Internet Explorer, earning it “Product of the Year” recommendations from PC World magazine.

Figure 13-2. Compare Firefox’s view of this Web site with Internet Explorer’s (shown in Figure 13-1) to see the results of Firefox’s built-in ad-blocking. Firefox also lets you open several Web sites simultaneously, each in its own tab. The tabs conveniently let you switch between sites with one click. A search box in the upper-right corner lets you perform quick searches on Google, or other sites you select, through the drop-down menu. Optional extensions—mini-programs written by third-parties—let you add things like a weather forecaster. And unlike Internet Explorer, searching for terms on the displayed page doesn’t block your view of the screen.

Quick searches. Firefox offers a built-in search box, shown in Figure 13-2, accessible from a little toolbar in the top right-corner of the browser window. Type your search words and Firefox sends them to Google, which instantly displays the results. You needn’t always search with Google, though. A drop-down menu on the search box lets you route your search to several different places, providing quick searches on Amazon, eBay, Wikipedia (an online encyclopedia), and other popular sites.

Find. When you want to search for a particular word on a Web page, Internet Explorer makes you type the word into an intrusive, and separate, onscreen window, which stays out front during the search, blocking your view. A search in Firefox, by contrast, takes place in a toolbar at the bottom of the window; as you type letters, Firefox quickly begins highlighting matches.

RSS. Firefox supports the increasingly popular RSS (Section 13.5) technology, letting you know when your favorite sites are updated with new content.

Extensions. Firefox hails from the open source school of code sharing, where programmers create versatile add-ons, called extensions, for their own benefit and then release them to the public, as well. That lets you add things like localized weather forecasters (see Figure 13-2), ad blockers, Macromedia Flash blockers, and zillions of other doodads to customize your browser.

Firefox’s tabbed interface, ad-and-pop-up blocker, built-in search box, and RSS reader make it a giant step up from Internet Explorer. Plus, the browser’s stable and easy to use, sticking with a clean design that emphasizes form over function. Should you need an extra function, chances are you’ll find it through one of the neat extensions (Tools → Extensions → Get More Extensions). Finally, Firefox is free, and automatically imports your Internet Explorer Favorites as it installs itself. It’s hard to ask for much more.

Firefox doesn’t support ActiveX (Section 9.4), and occasionally crashes when sites sense you’re trying to block their ads too aggressively. Just as with Internet Explorer, you need to download plug-ins (see the “Adding Plug-ins to Your Browser” box) to display content that uses Flash, Real Media, Adobe Acrobat, QuickTime, Windows Media Player, and Java. When you need a particular plug-in, most Web sites automatically direct you to the appropriate download link.

Setting up Firefox on your PC couldn’t be easier. Head to Firefox’s download site (http://www.getfirefox.com) and select Free Download. Double-click the downloaded file, and Firefox installs itself.

As it nestles down onto your hard drive, Firefox imports all your information from Internet Explorer: your favorites, browsing history, passwords, cookies, and the settings Internet Explorer uses to connect with the Internet. It also grabs Internet Explorer’s Autocomplete settings (Section 13.1.3), which lets the browser fill in some forms automatically when you first start typing a few letters or words.

When the installation’s complete, you get a personalized browser that’s ready to connect to the Internet. To launch the program, you have a few options: click the Firefox icon on your Start menu (Start → All Programs → Mozilla Firefox), on your Quick Launch toolbar (next to the Start button), and, depending on your installation choices, on your desktop.

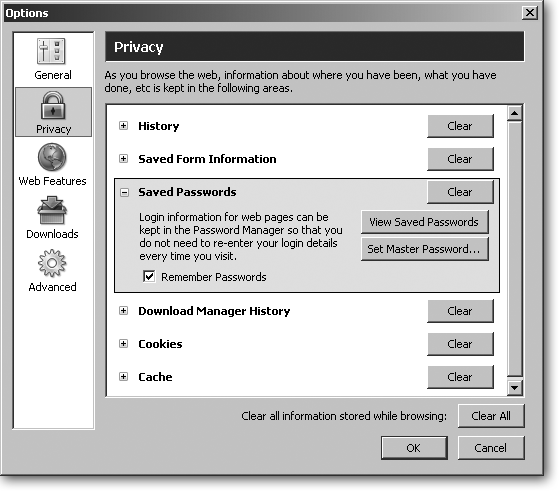

Firefox groups all its privacy controls in one area (Tools → Options → Privacy), where you can clear your browsing history, saved forms, saved passwords, cookies, download history, and temporary files—the detritus left behind as you browse Web sites. (Windows XP’s Disk Cleanup program—see Section 9.4—automatically deletes Internet Explorer’s temporary files, but it doesn’t delete those left behind by Firefox.)

To back up your Firefox Bookmarks (the equivalent of Internet Explorer’s Favorites), choose Bookmarks → Manage Bookmarks → File → Export. You can save the resulting Bookmarks.html file to a USB thumb drive (Section 9.2) or anywhere else for safekeeping. Just as with Internet Explorer’s exported Favorites, the Bookmarks.html file is a Web page containing clickable links of all your favorite Web sites.

Together, Internet Explorer and Firefox grab about 95 percent of the Web browser market, leaving two other browsers, Opera (http://www.opera.com) and Netscape (http://www.netscape.com), to battle for the remaining scraps. Netscape’s been pretty much abandoned, although it still attracts a following among Microsoft haters. Another longtime competitor, Opera, serves as a browser for several mobile phones and palmtop computers, making it familiar enough to attract some PC owners, as well.

Since so many Web sites require you to fill out forms and enter passwords nowadays, managing all this drudgery can quickly take the fun out of surfing the Web. Both Internet Explorer and Firefox help with these chores, but in slightly different ways.

Tip

To keep from juggling dozens of passwords, try a password manager like Access Manager (http://www.accessmanager.co.uk), 4uonly (http://www.dillobits.com/4uonly.html), or Password Agent (http://www.moonsoftware.com/pwagent.asp). When you enter the program’s single master password, you quickly gain access to all the other passwords safely guarded by the program.

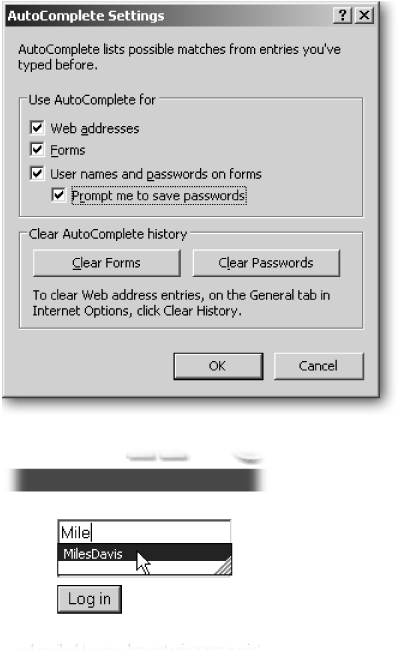

With a feature dubbed AutoComplete, Internet Explorer remembers items that you type into forms—including your passwords—saving you from probing your memory each time you visit a site. To change the way Internet Explorer handles your memorized form entries, adjust AutoComplete’s settings by choosing Tools → Internet Options → Content tab → AutoComplete. Once the AutoComplete Settings window appears (Figure 13-3), turn on or off the following items:

Web addresses. Turning on this checkbox tells Internet Explorer to remember the Web addresses you’ve typed into its Address bar. It’s great for people who manually type in lots of addresses, but not much of a timesaver if you browse mostly by clicking page links or site names on your Favorites list.

Forms. When you turn on this checkbox, Internet Explorer remembers items you’ve typed into online forms. This option is particularly helpful for automatically filling in oft-requested information like your name or address.

User names and passwords. This checkbox links your user name to your password; when you type your user name into one box, Internet Explorer automatically places the password in the adjacent box, as well. To be on the safe side, turn on the optional “Prompt me to save passwords.” That makes Internet Explorer ask permission before remembering a password, letting you pick and choose which sites should let you in automatically.

Figure 13-3. Top: Internet Explorer’s AutoComplete Settings window is your control center for deciding which Web addresses, forms, and passwords Internet Explorer automatically fills in for you. To wipe Internet Explorer’s memory clean, click either the Clear Forms or the Clear Passwords button, depending on which kind of info you want the program to forget. Bottom: When you start typing into a form on a Web page, Internet Explorer automatically presents your previous entry on a drop-down menu, letting you enter it with one click.

Firefox can help you fill out forms much the same way as Internet Explorer, although the program doesn’t automatically turn on that feature. To make Firefox remember your form info, click Tools → Options → Privacy → Saved Form Information and then turn on “Save information I enter in web page forms and the Search Bar.”

Firefox takes an extra step when remembering your passwords, in order to help you better protect them. Whenever you enter a user name/password combination into a Web site, Firefox asks you if it should remember that password, or never remember it. That lets you choose “remember” for most sites, but choose “never remember” for firms that store precious information, like your bank’s Web site. Firefox then stores your passwords in its Saved Passwords area (Tools → Options → Privacy → Saved Passwords), shown in Figure 13-4.

Figure 13-4. Firefox keeps track of your saved passwords in its Privacy section, along with related items: your browsing history, information you’ve typed into online forms, lists of files you’ve downloaded, your cookies, and your cache—Web pages you’ve viewed in the past. Click the Clear button next to any category to delete its entries. Or, to delete them all at once, click Clear All at the bottom of the window.

The Saved Passwords area gives you the following options:

Clear. Click here to delete all your saved passwords, pronto. Although this option’s handy when you hear a burglar walking down the hall, most people delete passwords individually by clicking View Saved Passwords, described next.

View Saved Passwords. A treasure trove when you need access to all your passwords. This button lists everything: a list of Web sites, the user names you’ve entered, and their accompanying passwords. If you’re switching to a password management program (as described in the tip on Section 13.1.3), visit here to harvest all your user names and passwords. If you spot a password that shouldn’t be listed, click its name and then click Remove to delete it.

Set Master Password. As an extra layer of security Firefox offers to create a master password to protect your password stash. If you create one by clicking this button, Firefox asks for that master password every time you fire up the browser. When you enter the password, Firefox continues coughing up your passwords automatically at sites requiring them. If you don’t enter the master password, Firefox still works, but doesn’t divulge any of your remembered passwords. That keeps thieves from turning on your stolen laptop, visiting your banking site, and transferring all your money into a PayPal account.

Remember Passwords. This checkbox, which is normally turned on, tells Firefox whether to remember the user names and passwords you type online. People working in high-clearance government jobs usually turn this box off. Most other people, however, leave it turned on for convenience.

Windows XP’s Service Pack 2 (Section 15.4) bestowed Internet Explorer with a pop-up blocker that keeps ads from jumping into your face. If you’re seeing a lot of pop-ups, make sure this feature’s turned on (Tools → Pop-up Blocker → Pop-up Blocker Settings). On the Pop-up Blocker Settings window, click the Filter Level drop-down list to change the blocker’s settings to Medium or High. Firefox can also automatically block pop-ups (go to Tools → Options → Web Features and turn on the Block Popup Windows checkbox).

Both browsers let you tailor your pop-up blocker by adding Web sites you deem friendly to an Exceptions List. That lets you call off the pop-up blocking dogs for sites that use pop-ups for good ends—an online map that springs up with helpful information, for instance.

Note

If you’re still seeing lots of pop-ups, even after activating these pop-up blocking features, your PC may be infected with spyware or adware. See Section 15.6.1 for help clearing out these menaces.

Internet Explorer doesn’t provide a way to stifle ads that appear as part of a Web page, but Firefox snips them away with a little work on your part. Since a small handful of large companies serve up most Web sites’ ads, Firefox lets you block images from those companies. When you spot a particularly obnoxious ad, right-click it and choose “Block Images from,” followed by the name of the company sending the ad. Blocking images from a few big ad-serving companies can reduce about 90 percent of the ads you see, making Web sites much easier to read. If you block something by mistake, remove its name from the Firefox’s Exceptions list (Tools → Options → Web Features → Exceptions).

After opening your browser, you’re ready to venture onto the Internet. But before you even start surfing you’ll probably notice a page patiently waiting in your browser: your Home page. Most browsers automatically open to a page that plugs itself or one of its creator’s products. To change the Home page to your favorite site—Google News (http://news.google.com), for instance—simply visit your favorite site. Then, in Internet Explorer, choose Tools → Internet Options → Use Current. From then on, Internet Explorer opens showing your favorite Web page. (In Firefox, do the same thing by choosing Tools → Options → Use Current Page.)

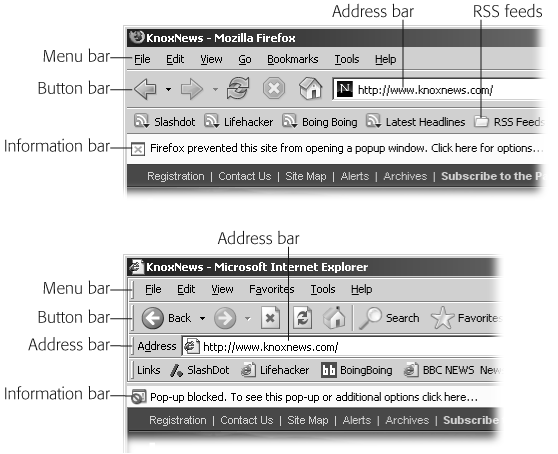

Your Home page serves as a starting point; buttons and bars on your browser, as shown in Figure 13-5, and described below, offer several ways to move from one site to another.

Figure 13-5. Firefox (top) and Internet Explorer (bottom) both offer similar screen options for navigating the Web, but with slight differences. Firefox refers to Web site shortcuts as Bookmarks; Internet Explorer calls them Favorites. Firefox also combines its buttons bar with its Web address bar (calling the duo a Navigation toolbar), leaving slightly more space for Web page display. The “radar” icons next to the links on Firefox represent RSS feeds (Section 13.5), letting you click the link to read the site’s headlines—without visiting the site itself.

Tip

If any of the Internet Explorer toolbars you see in Figure 13-5 are missing, choose View → Toolbars and click the missing bar’s name. If you still don’t spot the bar you want, it’s probably scrunched up on the right end of another bar. Here’s how to display it in full. Each bar sports a little vertical line on its left edge that serves as a handle. Drag the scrunched bar downward (off of whatever bar its jammed onto) so that you can see it in its full glory. Then position it where you want it. Once you’ve dragged the bar back in place, choose View → Toolbars → Lock the Toolbars to keep them from moving around. (Firefox doesn’t have the “moving toolbar” problem, as its two toolbars aren’t movable or resizable.)

Address bar. Type a site’s name into the address bar—http://www.nytimes.com, for instance—and press Enter to visit the New York Times Web site. (For a shortcut, type nytimes and press Ctrl+Enter; the browser fills in the tedious www and com stuff.)

Menu bar. The words on this bar all offer drop-down menus; the Favorites menu, for instance, displays icons of your favorite Web sites. Click Favorites and then select your favorite site’s name from the drop-down menu for a quick visit. To add a site to your Favorites menu in Internet Explorer, right-click anywhere on a page and choose “Add to Favorites.” (In Firefox, right-click the page and then choose “Bookmark this page.”) Other popular menu choices include Print (File → Print; covered in Chapter 4) and Save Web Page (File → Save As; Section 13.4.3.4).

Standard buttons. Click the left arrow icon to revisit the page you just left; when you’re done, click the right arrow to return to the page you started from. (See the little black arrows beside those two icons? Click either of them to see the last five Web pages you’ve moved through—either forward or backward—since opening your browser.)

Links bar. The shortcut buttons stored here provide one-click access to your most favored Favorites. To add a currently displayed site to your Links bar, drag its icon from the Address bar to your Links bar.

Information bar. This bar appears along the top of the main browser window when your browser’s stopped something from appearing: a blocked pop-up ad, for instance, or a possibly harmful program download.

Most of the time, you’ll jump from one Web site to another without touching your browser’s menu bars and buttons. After all, the reason the Web’s more popular than free candy is its legendary ease-of-navigation: just click underlined or highlighted words on a Web page and off you go to the page the link represents.

The rest of this section explains how to find sites, print or save their information, forward pages to friends, and download files.

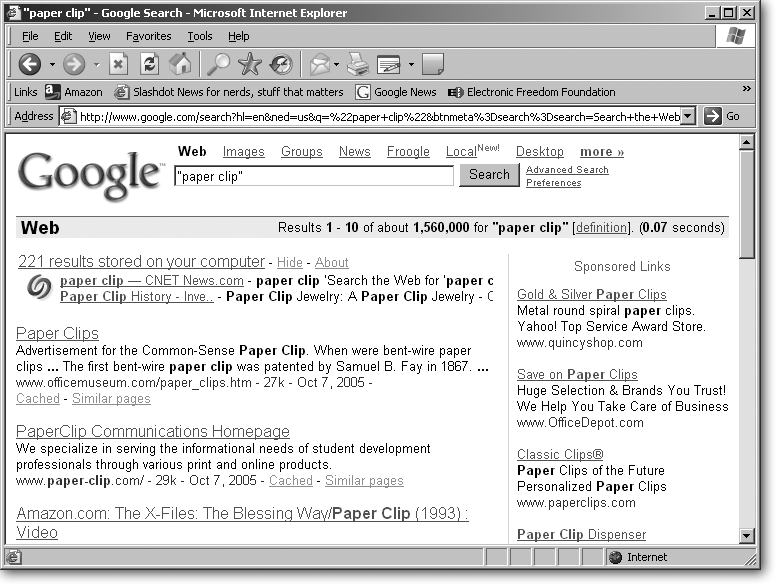

The Internet contains more information than all the nation’s phone books; what it lacks is a convenient centralized directory. To help you pull what you need from the giant stack of pages, several sites offer a searchable index. The best by far is the now famous Google (http://www.google.com), shown in Figure 13-6. Google’s even crept into street lingo as a verb: “I Googled him before going out on our date.”

When you’re ready to start your own search, type what you’re looking for into Google’s search box and click Google Search; Google then lists the sites that match your query, ranked in order of popularity (among a few other factors).

Figure 13-6. Google finds 1,560,000 sites that contain the exact term “paper clip,” and then displays the results in the center of the window (the right side features links from advertisers). Click Images to search for pictures of a paper clip; click News to find current newspaper and magazine articles mentioning “paper clip.” The Groups link takes you off to a section of Google featuring Usenet groups, an elderly branch of the Internet reserved mostly for categorized discussions. Froogle finds online shops that sell paper clips. And if you install Google’s Desktop Search program (http://www.desktop.google.com), Google also sniffs out mentions of “paper clip” on your PC.

Following these few rules will help you pull the best information out of Google:

Put search strings in quotes. Putting quotes around “paper clip” searches for those two words as a single term. Without the quotes, Google retrieves sites that contain the word “paper” and “clip,” but not necessarily the phrase “paper clip.”

Mind your ANDs and ORs. If you search for paper OR clip, Google locates pages mentioning either “paper,” or “clip,” and then displays the combined results. Be sure to capitalize the word OR; otherwise Google ignores the word, just like it ignores other small words: a, an, I, the, of, for, how, it, in, is, and so on. Google automatically considers a search for the term paper clip to be a search for paper AND clip. That means it will locate any site mentioning both words, even if they’re not adjacent.

Weed out unwanted words by using the minus sign (-). When you’re looking for references to John Wayne that don’t talk about his movie career, weed out the word “movie” by searching for "john wayne“–movie.

Google offers oodles of other search features and companion programs, all neatly documented in Google: The Missing Manual.

Tip

Firefox offers an easy way to conduct a quick search using any word or phrase you see on a Web page. To do so, select a word or short phrase—the words “celery stalk” for instance—right-click the selected item, and then, from the shortcut menu, choose “Search Web for ‘Celery Stalk’.” Firefox sends the phrase to Google and displays the search results.

Although Google’s the most popular search engine by far, it’s not the only game in town. The three biggest contenders are Yahoo (http://www.yahoo.com), Ask Jeeves (http://www.askjeeves.com), and Microsoft’s own MSN (http://www.msn.com).

To quickly print a Web page using Internet Explorer, choose File → Print → Print. In Firefox, choose File → Print → OK.

However, when you do this, you often get a page that runs off the paper’s right-hand margin. That’s because Web site designers work hard to create sites that look nice on a monitor of any size or resolution (Section 3.8.1), but they rarely create sites that unfurl themselves neatly onto a piece of paper.

If you’re lucky, you may spot a "Print this site” link near the page’s top. Click that for a reformatted page that fits neatly onto a printed page. But should you run across a site that gives you trouble when printing, Section 4.9 explains the best ways to print an entire Web page or a small portion of it.

Web sites contain a vast amount of reference material that’s handy to keep around, even when you’re not online. You may want to snag a photo, grab your flight schedule, or save an entire Web page that explains race track betting systems.

Those who don’t mind wrestling with a few settings may even want to save several Web pages from a site automatically, stocking your laptop with the newspaper’s business section for your morning commute.

Saving a portion of a Web site—a single Web page, a photo, or a snippet of text—is easy. Automatically saving a good chunk of Web site takes much more work, although Internet Explorer makes a valiant attempt to help you (for details, see Section 13.4.3.4). This section explains how to stuff small bits and pieces of a Web site—or a thick slab of its contents—onto your PC for viewing even when you’re not connected to the Internet.

Any Web browser lets you save any photo you spot, which can be handy for grabbing and printing out a quick map of Disneyland or adding an album cover to your new They Might Be Giants folder. To grab any image from the Internet, right-click it to display the pop-up shortcut menu. In Internet Explorer, choose Save Picture As; in Firefox, choose Save Image As. Navigate to the folder where you want to save your image and then click Save.

Tip

Internet Explorer normally offers to save your right-clicked pictures as JPG files, the same compressed format used by digital cameras. But if you only see an option to save photos as bitmap files—uncompressed files about 10 times as large—fix the problem by flushing your Temporary Internet Files folder (Tools → Internet Options → Delete Files).

If you want to grab only a few bits of text from a Web page—your flight schedule, for instance—you need to first select the information. To do so, click the information’s top-left corner, and then—while holding down your mouse button—drag across to the passage’s bottom-right corner. The selected information changes color, letting you know what you’ve selected.

Next, right-click the selection, copy it (Ctrl+C), and then paste it (Ctrl+V) into the word processor of your choice. Even Notepad (Start → All Programs → Accessories → Notepad) or WordPad (Start → All Programs → Accessories → WordPad) can catch pasted text, which you can then save as a text file.

When you spot something irresistible in a newspaper or magazine, it’s easy enough to tear out that page for safekeeping. You can do the same thing with a Web page, saving it to your hard drive for later reference. Internet Explorer (File → Save As) and Firefox (File → Save Page As) both offer “Save as type” drop-down menus for saving pages in the following formats.

Web Page, complete (*.htm;*.html). This format creates two items: a folder containing all the page’s images, and a file containing the site’s text and HTML codes—the instructions for mixing the images and text to recreate the page. To see the Web page in your browser again, double-click the saved page’s file. Your browser dips into the image folder and recreates the Web page’s contents, just as it looked the day you saved it.

Separating a page into a file and folder can be a tad awkward, though, especially when you save them into an already crowded folder.

Web Archive, single file (*.mht). The best option for capturing an entire page. This format compresses the entire page into a single file, making it much handier to copy to a laptop, another PC, or even a USB drive (Section 9.2). (Firefox doesn’t offer this option, unfortunately, but Internet Explorer does.)

Web Page, HTML only (htm;*.html). Another not-so-useful-for-civilians option. This format copies the file’s text and underlying coding, but leaves out the figures. Opening these types of files when you’re not connected to the Internet shows the text positioned around blank areas where the pictures used to be. If you are online, the pictures appear correctly—if the Web site hasn’t deleted them or moved them to a different place since the time when you saved the page.

Text File (*.txt). This format works great to scrape all the text off a page and place it in a file, ready for editing in a word processor. Then you can tweak the paragraphs, editing them into a neatly formatted document. That makes this option handy for grabbing recipes, directions to a friend’s house, and other important words.

Internet Explorer can save a Web site to your PC automatically for your offline viewing pleasure. (It calls this process synchronization.) That’s a great time-saver, since this feature saves you from having to wake up at 4:30 each morning and manually save the 2,900 new pages that appeared overnight on your favorite newspaper’s Web site. But before trying to stuff the entire New York Times onto your laptop for browsing, take heed of a few cautions.

Saving an entire Web site can be tricky because you need to let Internet Explorer know where to stop. Web sites contain links to other Web sites, which in turn point to other Web sites in a never-ending spiral of information. By saving an entire Web site, including every site it links to, and all the linked sites on those sites, you could find yourself trying to stuff the entire Internet onto your laptop.

Thankfully, Internet Explorer lets you adjust the spigot so that you automatically scoop up a select few pages rather than the whole site. The trick is to identify and save a single page and then decide which of that page’s links should still bring up information when you click it while you’re offline. The following steps take you through the process:

Note

Unlike Internet Explorer, Firefox doesn’t offer a built-in way to gather portions of a Web site automatically. The Scrapbook extension (Tools → Options → Get More Extensions) adds that ability, but without the automated scheduler: You must tell Scrapbook each time you want to gather a page and its links.

Bookmark (Favorites → Add to Favorites) the page you want to designate as Page Zero: the page that Internet Explorer uses as the synchronization starting point.

This could be your newspaper’s home page, if that’s where you normally begin reading. But if you always jump to a particular spot—the newspaper’s local section, for instance—create a link to that particular page.

Right-click the Web page’s name from the Favorites menu (or the Links toolbar), and then choose “Make available offline.”

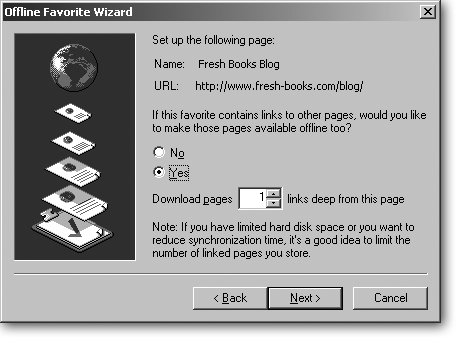

This summons the Offline Favorite wizard, which helps you decide which parts of the site you’ll save and which parts you’ll leave behind.

Read the wizard’s introduction page, and then click Next.

If you visit this wizard often, banish this introductory page by turning on the “In the future, do not show this introduction screen” checkbox.

Decide whether to gather any linked pages, and how many to gather; then click Next.

The wizard’s first real question, shown in Figure 13-7, asks whether you want to gather that page’s linked pages, as well. Your choices are pretty straightforward.

Figure 13-7. Choosing Yes and then choosing “1” tells your PC to download that linked page, plus every page that’s linked to from that page. That’s a large chunk of information, but it ensures that every link on the downloaded page also brings up more information. Although the wizard lets you download up to three links deep, that level of page-collecting could gather more information than will fit onto your PC (depending, of course, on the size of your hard drive).

No. Click No to gather just the page itself—the online newspaper’s front page, for example—but none of its linked pages. This option works much like tearing off the front page of a real newspaper and tossing it into your briefcase. You can read the day’s headlines and the first few paragraphs of each story. However, it leaves you dangling when you want to read the rest of an article after that front page teaser.

Choosing No works great for grabbing blogs, which usually stuff most of their content on one long, flowing page.

Yes. Click Yes to gather that page’s linked pages, as well. Since the wizard’s not, er, magic, it can’t predict which story you’ll find interesting enough to continue reading. So the wizard plays safe by grabbing every page linked to by that first page. This is risky on many sites. Try it on Google News, which links to several hundred newspaper articles, and the download could take several hours. But this may work on small sites or small newspapers.

Choosing Yes gives you one more option, also shown in Figure 13-7: how many pages deep do you want to grab? Normally, the wizard leaves the setting at “1,” which grabs all the pages referenced by the first page. That’s fine for most people, since it lets you click any link to see more information.

Downloading two links deep grabs not only those same links, but every page linked to by those second-tier pages, as well. Be careful here—grabbing more than one link deep can take a very long time to download, and, depending on the site, fill a huge chunk of your hard drive.

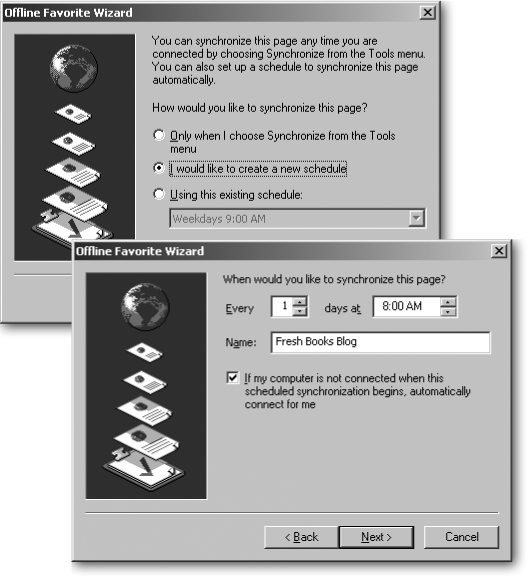

Tell the wizard when to synchronize your pages, and then click Next.

The wizard gives you three options for synchronizing your pages, as shown in Figure 13-8, top, and explained here:

Only when I choose Synchronize from the Tools menu. This lets you grab the pages whenever you choose Tools → Synchronize. It’s ideal for casual surfers who want to grab the site only occasionally—as well as for experienced Web-heads who want to synchronize several times during the day, perhaps for the morning and evening commutes.

I would like to create a new schedule. This lets you automate the page-grabbing process so that it happens once a day. Click this option and click Next to choose the days and times for your PC to grab the pages, as shown in Figure 13-8, bottom. To have your paper’s front page waiting on your laptop each morning, choose “Every 1 day(s) at 5 AM,” for instance.

Using this existing schedule. This option, if it appears on your screen, offers a drop-down menu for selecting previously created schedules. If you spot a schedule that meets your needs, choose it; otherwise, create your own schedule by using the previous option.

Enter a user name and password if the site requires it, and then click Finish.

Finally, the wizard asks if the site requires a logon name and password. Enter them, if needed, and then click Finish to close the wizard.

Depending on your choices, your site will be waiting for you at the scheduled time or ready for the plucking when you right-click its name from the Favorites menu and choose Synchronize. Depending on the level of your links, a broadband connection should be able to grab everything in a few minutes; give it much longer if you’re using a dial-up service.

Figure 13-8. The wizard offers three ways to download your requested pages. Top: To choose your own download schedule, choose “I would like to create a new schedule.” That brings up the window below. Bottom: Choose an exact time of day for automatically downloading your selected pages. If you use a dial-up connection, turn on this page’s “If my computer is not connected…” checkbox. It lets your computer dial the Internet at the right time, connect, download your requested pages, and hang up when finished.

To read the site when away from the Internet, choose File → Work Offline, and then click the link with your stored pages.

To cancel an automated synchronization that’s hogging too much space or causing other problems, choose Tools → Synchronize and then turn off the checkbox next to the problem site’s name.

Note

If your synchronized site still grabs too much information, you can fine-tune it with some additional, well-hidden settings: Tools → Synchronize → Setup. From the list of synchronized sites, click your site’s name and then choose Properties → Download. That page offers oodles of additional options that Microsoft describes on a page (http://support.microsoft.com/?kbid=196646) at its Knowledge Base (Section 17.6) Web site.

When you spot a Web page that would be perfect for Uncle George, given his interest in African honey ants, let him know. Most browsers offer two ways to alert friends to Web sites of interest. Both methods open your email program, create a new message containing either the page itself or its link, and wait for you to address it and then click the Send button. But some subtle differences exist:

Send → Link by Email. Known as Send → Link in Firefox, this method emails only the Web page address, packaged as a clickable icon that directs the recipient to the site. This option doesn’t send any part of the page, just a clickable link that scoots the recipient to the Web page.

This method works well when you just want your friend to know about the site itself; it doesn’t matter if the particular page that excited you changes slightly, perhaps showing a different species of honey ants by the time your Uncle clicks the link.

Send → Page by Email. Meant for recipients who might not have a constant Internet connection, this technique sends the Web page (stored in the “Web Page, HTML only” format described on Section 13.4.3.4) along with the link. When the recipient opens the link, he sees the Web page’s text and formatting, but not the photos or figures—unless he’s connected to the Internet, in which case his PC dashes off, fetches the images, and properly plugs them into the Web page. (If he’s offline, all he’ll see in place of the images are empty boxes.)

This method works best when you want the recipient to read that page’s text as it looked the moment you visited it. For instance, the page may have profiled honey ants in Zimbabwe, and you know Uncle George cares about that particular region only. By clicking the link you emailed, your uncle can read the Zimbabwe article even if the live Web site has already begun profiling Australian honey ants.

File → Save As → Web Page, complete. This option (covered on Section 13.4.3.1) lets you save a mirror image of an entire Web page—images and text. After saving the page, you need to manually open your email program, create a new message, and then drag the saved Web page—both its file and the folder containing its files—into your email. Then send it off. The recipient then sees the same, identical Web page you saw and can save it on her hard drive for reference. (Firefox calls this File → Save Page As → Web Page, complete.) This procedure’s a bit more work—both for you and your recipient—but it’s the best way to send a complete replica of the page you want to share.

But no matter which method you use, some recipients may have trouble opening your attachment. Emailed links contribute to a large amount of viruses, fraud, and general Internet unhappiness, so many PC security programs (including antivirus programs and some firewalls) either strip your emailed link from the email, prevent your recipient from opening it, or rename the link so it won’t open when double-clicked.

To avoid these problems, just copy the site’s link from your browser’s Address bar, shown earlier in Figure 13-5, and then paste the text into the main body of your email message. To do so, select the link by clicking anywhere in the Address bar and then press Ctrl+A; copy the selected link by pressing Ctrl+C, and then paste the link into your email message by pressing Ctrl+V.

That gives your recipient a backup plan. If his email program has trouble with your attachments, he can still paste the link into his Web browser’s Address bar and visit the page. It’s not fancy, but it serves your main objective: letting someone know about a site he might enjoy.

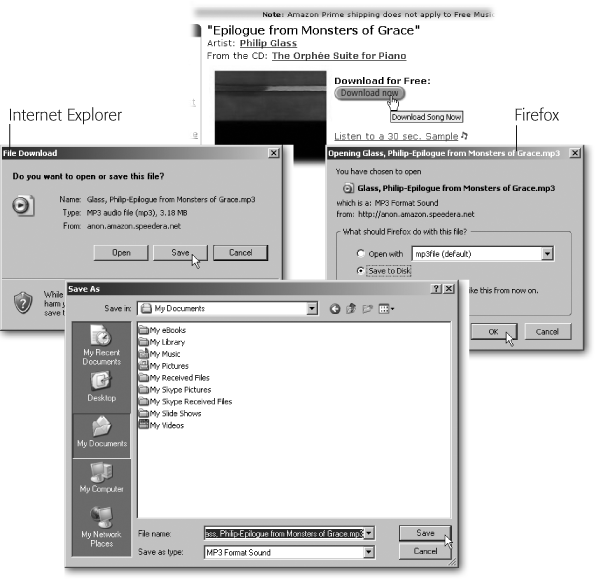

Many Web sites offer files for downloading: programs, music, books, and just about anything else that can be stored in a computer file. Most sites take one of two approaches to file-downloading:

Automatic download. To simplify the process, some sites graciously offer a button named “Download now” or “Download,” as shown in the top of Figure 13-9. When you click the button, Internet Explorer may ask if you want to Run or Save the file (see Figure 13-9, middle). Choose Save, not Run. (In Firefox’s query window, choose “Save to Disk,” not “Open with.”) Whichever browser you’re using, when Windows’ Save As window appears, choose Save.

Figure 13-9. Top: When a site offers a Download or “Download now” button for downloading a file, click the button. Middle: When Internet Explorer’s File Download window appears (left), choose Save. (Choosing Run makes Windows try to run or play the file immediately, which is a security risk.) In Firefox’s equivalent window (right), choose “Save to Disk.” Bottom: In Windows’ Save As window, navigate to the folder where you’d like to place the file, and then click Save. The file then begins downloading onto your PC, taking anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes, depending on the file’s size and your connection speed.

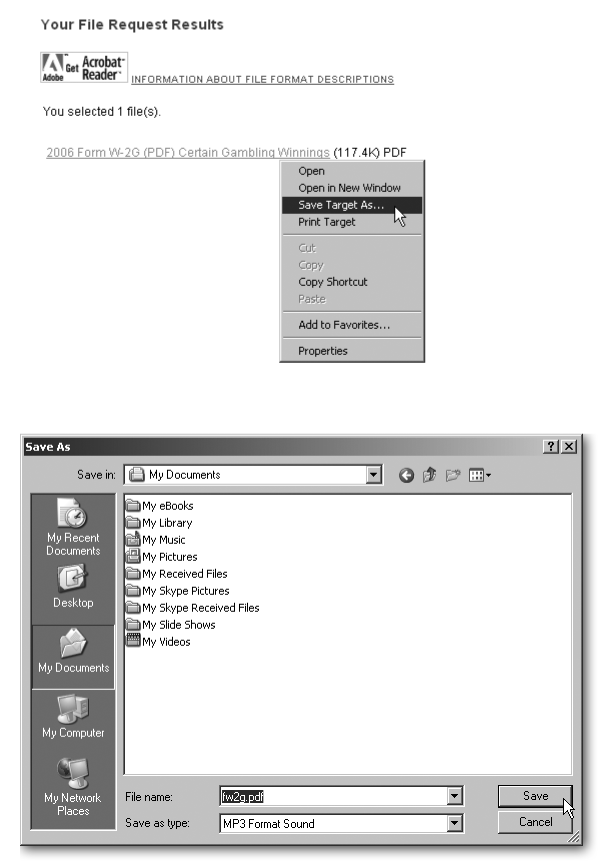

Link. Smaller sites often skip the convenience of an automatic download. Instead, they list the file’s name as a link, often as an underlined word or phrase, as shown in Figure 13-10. You then need to prod your browser into downloading the file. Right-click the file’s link and then choose Save Target As. (Firefox calls it Save Link As.) When Windows’ traditional Save As dialog box appears, shown at the bottom of Figure 13-9, navigate to the folder where you want to save your file, and then click Save to start the download.

Figure 13-10. When a Web page doesn’t offer a download button, download the file yourself by right-clicking the file’s name. From the shortcut menu, choose Save Target As. (Firefox calls it Save Link As.) When the Save As window appears, navigate to any folder you like and then click Save.

If you anticipate saving a lot of downloaded files, open your My Documents folder, and create a new folder named Downloads (File → New → Folder). Downloading files to a Downloads folder makes them much easier to find later.

Warning

Before opening any downloaded file, be sure to scan it with an up-to-date virus checker (Section 15.6.3).

Internet hounds love to visit their favorite sites, always seeking out fresh content. But if the site doesn’t have anything new, it’s a wasted trip. RSS (which stands for either Really Simple Syndication or Rich Site Summary, depending on who you ask) solves that problem by regularly publishing updates of newly created headlines (and short summaries that usually accompany these headlines). Instead of clicking through sites to see whether they’ve added new material, you glance over headlines (also called "news feeds”) from all your favorite sites. When you spot something interesting, give it a double-click to fetch that specific story for a read.

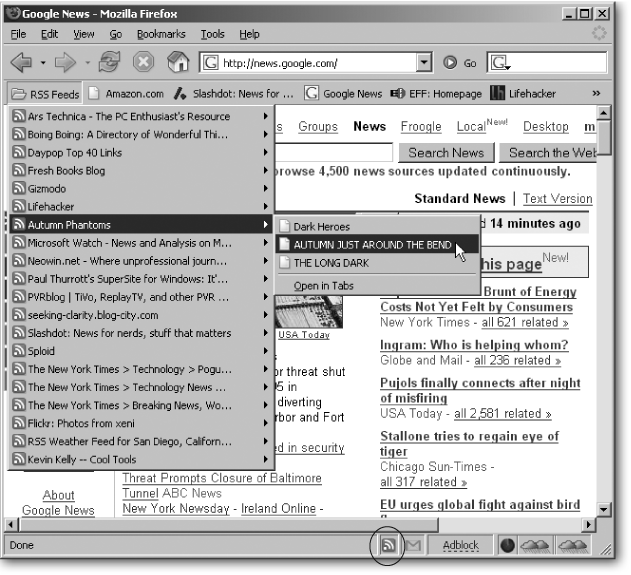

Receiving headlines requires a program called an RSS reader, also known as a news aggregator. Some sit in your Desktop’s taskbar, sending announcements of newly published stories. Others function as standalone programs, letting you browse through interesting feeds during your spare time. Still others are built into browsers like Firefox, as shown in Figure 13-11.

Figure 13-11. The Firefox Web browser comes with a built-in RSS reader that creates live bookmarks. Whenever you open Firefox, it dashes off to each site, collects the latest headlines and presents them to you on menus sprouting from the site’s bookmark. That saves you time, letting you jump to the good stories, and ignore those that are boring. When you spot the little orange Live Bookmark symbol in Firefox’s bottom-right corner (circled), you know you’re viewing a site with RSS support. Click the link, and Firefox bookmarks the site, letting you view its RSS list for new stories.

Not all sites support RSS, however. Sites currently offering RSS support include Flickr (Section 5.5.2.1), blogs, and many online magazines and newspapers. RSS is growing in popularity, so expect to see more RSS live bookmark symbols in Firefox, like the one circled in Figure 13-11.