Most people get acquainted with memory cards the first time they buy a digital camera and need some “digital film” to go along with it. Others buy USB drives—memory cards connected to a handy USB plug—to carry around their data and pictures of loved ones.

These digital doohickeys are so convenient that it’s easy to forget about the technological marvel inside: the hidden flash memory that contains special circuits with thousands of tiny switches. When the computer (or camera) saves information to the card, the switches flip into a certain position. To retrieve the information later on, the computer reads the switches’ positions.

The switches stay in place when flipped, letting the card remember its information for about 100 years, at least according to manufacturers’ claims. Count on about a decade or so—more than enough time to dump the information onto your PC. Unlike the main memory inside your computer (also known as RAM), which for-gets its information when your PC’s turned off, flash memory doesn’t require batteries to keep its switches flipped.

This chapter explains the different types of memory cards and USB drives you’re likely to encounter, how to tell them apart, which ones you need, and how to write and read information to and from them.

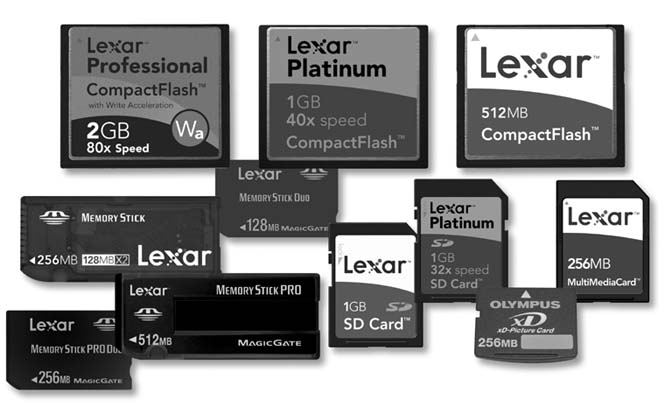

Memory cards began life in 1992 as PC Cards. Back then, they provided the only way to boost a laptop’s meager memory: slip a credit card–sized PC Card into the laptop’s PC Card slot, and you instantly gave your laptop an extra megabyte or two for calculations or storage. Fifteen years later, small memory cards like the ones shown in Figure B-1 add storage to thousands of digital cameras, MP3 players, cell phones, and other small gadgets.

Figure B-1. Having evolved for nearly 15 years, memory cards now come in a wide variety of shapes and capacities to fit in digital cameras, cell phones, portable MP3 players, memo recorders, and other gadgets. Top: Three CompactFlash cards. Bottom, left: Four Memory Stick and Memory Stick Duo cards. Bottom, right: Two SecureDigital cards, an xD Picture Card, and a MultiMediaCard.

The vast majority of memory cards live inside digital cameras to store photos, and for that purpose, you want a huge card. Our parents worried about how many rolls of film to carry to Disneyland; with large memory cards, you never need to worry about running out of film.

Oddly enough, a memory card’s physical size doesn’t affect the number of photos it holds. Instead, cards come rated by their storage capacity in megabytes, just like hard drives (Section 9.2) and CDs (Section 10.3).

To figure out the card size you need, take a look at Table.B-1, which lists the number of photos your camera can stuff onto different sizes of memory cards. To see where your camera fits in, locate your camera’s megapixel capacity (Section 5.7) along the top row. Below that, each row lists how many photos the camera can store on different sized cards—for example, a 3-megapixel camera can store about 106 photos on a 128 MB card.

Note

Most digital cameras let you choose between three picture quality settings: Normal, Fine, and SuperFine. The photo capacities listed in Table B-1 are based on a camera set to the Fine setting.

Table B-1. The number of photos a camera can fit onto a memory card

2 MP | 3 MP | 4 MP | 5 MP | 6 MP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

32 MB | 35 | 26 | 16 | 12 | 10 |

128 MB | 142 | 106 | 64 | 51 | 40 |

256 MB | 284 | 213 | 128 | 102 | 80 |

512 MB | 568 | 426 | 256 | 204 | 160 |

1 GB | 1,137 | 853 | 512 | 409 | 320 |

2 GB | 2,275 | 1,706 | 1,024 | 819 | 640 |

4 GB | 4,551 | 3,413 | 2,048 | 1638 | 1,280 |

Your photo capacity will vary slightly because photos always differ in size. Scenes with lots of tiny details—a dense forest, for instance—create larger files than photos of distant orange sunsets.

Although memory cards go hand-in-hand with digital cameras, the flat little cards come in handy in several other situations:

Moving files. Cards provide a quick way to shuttle information between laptops, desktop computers, palmtops, portable music players, and other cameras. Add card readers to your laptop and desktop PC, and your humble memory card becomes a high-capacity floppy disk for speedy transfers of large files—your MP3 collection, for instance. Most Sony laptops come with a tiny slot in one side to read Memory Sticks, the flash card format used by most Sony devices.

Adding accessories. Some companies slip something else into a memory card’s housing—a wireless network adapter, for instance. Slide that wireless antenna card into your Palm or Pocket PC’s memory card slot, and you’ve added wireless access for browsing the Internet at the coffee shop.

Other accessories piggybacking inside or atop memory card-sized housings include modems, Global Positioning Systems, barcode scanners, magnetic stripe readers, and VGA ports. Some cards even come with a tiny digital camera mounted on top, turning your palmtop into a digital camera.

Unfortunately, many memory card-sized accessories require drivers (Section 16.5.4) specifically written for your gadget’s make and model. A CompactFlash-sized camera from a Casio Pocket PC, for example, may not work in an iPaq Pocket PC or when plugged into your PC’s card reader.

Convenience printing. Many new printers and photo kiosks (Section 4.7) print photos from an inserted memory card, provided the photos don’t need much in the way of editing.

A credit card–sized PC Card worked fine for laptops, but as devices got smaller, so did the need for smaller cards. Each generation of smaller gadgets has produced a smaller storage card to match, often half the size of the card that came before. Here are the memory cards used today.

Tip

When choosing a new digital camera, give extra points to one that uses the same memory cards as your old model; that way, you can recycle your old cards.

The CompactFlash format started the race toward smaller flash cards. Exactly half the size of the credit card PC card that preceded it by two years, these sturdy plastic cards (see Figure B-2) still work with more devices than any other.

CompactFlash cards are fairly inexpensive, widely sold, and rugged. The largest cards hold hundreds, perhaps thousands, of photos. But they’re chunky compared to the latest batch of card formats, which keeps them out of the tiny camera market.

Figure B-2. Left: If you have trouble pulling out your CompactFlash card, place a piece of tape over its outside edge. A tug on the tape easily pulls the card out of the slot. Right: Type II CompactFlash cards (left), used for Microdrives and many CompactFlash accessories, are slightly thicker than the more common Type I CompactFlash cards (right). Not all cameras or gadgets can handle the extra thickness of a Type II card.

The end of a CompactFlash card contains two rows of tiny holes along one edge, as you can see on the two cards in Figure B-2, right. As the card enters whatever kind of slot is holding it (a camera or a card reader, for example), those holes neatly align with the slot’s two rows of pins—if you’re lucky. If you’re not lucky, the card enters the slot at a slight angle, bending the pins. If two bent pins keep your card from fitting in, try poking a toothpick inside the slot to separate the bent pins; it doesn’t take much force to correct their posture. If that fails, straighten them with a pair of ultrathin needle-nose pliers or tweezers, which you can find at most bead stores.

CompactFlash cards come in two types, Type I, and the slightly thicker Type II (both shown at right in Figure B-2).

Type I. Almost all CompactFlash memory cards sold today come in Type I thickness, and they work in every CompactFlash digital camera. You can’t go wrong buying a Type I card.

Type II. Some manufacturers began cramming accessories like network adapters into a slightly thicker CompactFlash casing. To accommodate the cards, most palmtops come with slightly thicker slots that take either type of card. Most professional cameras also come with larger slots that accommodate either type of CompactFlash card, or Microdrives, described next.

Not wanting to be left out of the memory card game, IBM sent its hard drive engineers to the drawing board with a magnifying glass. They returned with a hard drive stuffed inside a CompactFlash card’s casing, and called it a Microdrive, shown in Figure B-3.

Figure B-3. Smaller than your average hamster, Microdrives are miniaturized hard drives crammed into a CompactFlash card’s housing. They work in almost any device that accepts a CompactFlash card, but with two restrictions. The cards are slightly thicker than most CompactFlash cards (Figure B-2, right, shows the difference), and they draw more voltage. The extra voltage requirements overpower some devices and drain the batteries faster on others.

The iPod Mini once provided the biggest market for Microdrives, as it used both the 4 GB and 6 GB sizes. Apple replaced the iPod Mini with the flash memory-based Nano, which attaches a memory card’s guts—its memory chip—directly to the player’s circuitry. Professional photographers now make up the largest Microdrive market.

Since Microdrives contain moving parts (rather than flash memory), they’re a bit more fragile than CompactFlash cards. But strangely enough, those tiny hard drives cost less per gigabyte than flash memory, keeping them a strong contender in the memory card market.

By 1998, Sony knew the flash memory market was growing too large to ignore. Instead of adopting an existing format, the company created its own: the Sony Memory Stick, shown in the bottom left corner of Figure B-1. Memory Sticks work in Sony’s MP3 players, laptops, cameras, cell phones, and palmtop computers. Memory Sticks come in three flavors:

Memory Stick (MS). Sony’s first Memory Sticks set the card’s dimensions—about the size and thickness of a stick of chewing gum. The card’s capacity maxed out at 128 MB, which worked fine for the cameras of the day; Sony’s early cameras couldn’t take very high-resolution photos.

Memory Stick Select. Although Sony needed higher-capacity cards, all its devices handled only 128 MB. To solve the problem, Sony stuffed two 128 MB chips inside a single memory stick and added a switch on the card. When you filled up the first memory bank, you stopped shooting, turned off the camera, extracted the card, flipped the switch to the second memory bank, reinserted the card, and cursed Sony for such a dumb idea.

Memory Stick Pro. Sony solved the low memory problem in 2003 with its speedier, higher capacity Memory Stick Pro. Although the same size as the older Memory Sticks, these new cards don’t work in most pre-2003 Sony equipment. The few items that can handle the newer cards require a firmware upgrade (a maneuver described in the online appendix, “Fixing More Difficult Problems,” available on the “Missing CD” page at http://www.missingmanuals.com), downloadable from Sony (http://www.sony.com).

Memory Stick Pro Duo. As their gadgets shrunk, Sony chopped its Memory Stick Pro in half, creating the Memory Stick Pro Duo. The Memory Stick Pro Duo still works with Memory Stick Pro-ready cameras or palmtops if you slide the little guy into a little adapter before pushing it into the slot.

Memory Sticks are your obvious—and only—choice for your Sony gear. Luckily for consumers, many other manufacturers now sell the Memory Stick format, drastically lowering the price.

Originally designed as a digital “album” for selling music and other copyrighted material, Secure Digital cards include built-in copyright protection to keep people from copying the card’s contents. Although the music industry remained suspicious of the concept, the digital camera industry loved the card’s small size and low power drain. Today, the Secure Digital card’s found in most pocket-sized digital cameras, which simply ignore the card’s security features.

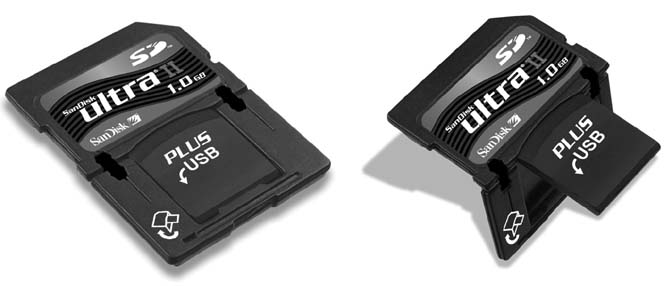

SanDisk’s Ultra II SD Plus Secure Digital card, shown in Figure B-4, looks like any other Secure Digital card and fits neatly into any Secure Digital slot. But when you’re ready to copy the information to your PC, fold the card in half to expose a USB connector that plugs directly into a PC’s USB port for quick-and-easy transfers.

By sticking the connector directly onto the card, SanDisk helps you bypass both a card reader and a camera, leaving travelers with one less thing to carry around.

Secure Digital cards have two close relatives:

Mini Secure Digital (Mini SD). Proving that cards can never be too small, Mini Secure Digital cards aim where no card could go before: small cell phones, miniature cameras, and other bite-sized objects. Half the size of the already small Secure Digital cards, Mini Secure Digital cards are about the size of a dime.

MultiMediaCard (MMC). Secure Digital cards and MultiMediaCards look almost identical. SD cards won’t work in MultiMediaCard slots, however, although MultiMedia Cards work in some SD slots. MultiMediaCards also lack the sliding write-protect latch that keeps you from accidentally overwriting your files. That’s okay. It’s an older format on its way out.

Figure B-4. Is it a USB drive or a memory card? Actually, it’s both. SanDisk’s Ultra II SD card slides into a Secure Digital slot. But it turns into a USB drive when you fold it in half, exposing a sliver of a USB connector. The flat connector pushes into a standard USB port, letting you copy your photos to your PC. The design wins for creativity and versatility, but be extra careful with its little plastic hinges.

One of the earliest memory cards, SmartMedia’s paper-thin card caught on with some pre-2001 digital cameras, mostly those by Olympus and Fuji. The card maxed out at 128 MB, though, while the CompactFlash and other cards kept growing. It’s been abandoned in favor of newer card formats.

Olympus, Fuji, and Toshiba created this card, shown in the lower-right corner of Figure B-1, to replace the aging SmartMedia card. With so many other formats to choose from, xD Picture’s been slow in catching on, and it works only in some Olympus and Fuji cameras. You may have trouble finding photo-printing kiosks (Section 4.7) that accept these.

Most cameras come with a cable that plugs into your PC’s USB port for Windows XP to suck out the photos (Section 5.2). For quicker transfers that don’t drain your camera’s batteries, attach a card reader to your PC (Section 5.3). The best card readers handle every card format, letting you read your cards, your friends’ cards, and the cards of any cameras you’ll be buying over the next few years.

Memory cards are some of the sturdiest data containers around. Scratches don’t hurt them, which is something you can’t say about CDs and DVDs. Unlike hard drives, you can drop them from 10 feet up without damage. SanDisk’s Extreme III CompactFlash cards, created for professional photographers, will cling to your data long after your computer (and your fingers) have stopped working, boasting an operating range from -13 to 185 degrees Fahrenheit.

Some companies like ATP Electronics (http://www.atpinc.com) build cards designed both for extraordinarily rough conditions and the amusement of your friends. You can freeze the card, and then boil it in water without harming the data.

As for the run-of-the-mill cards currently inside your camera bag, follow these guidelines to keep them reasonably safe:

Don’t turn off your camera prematurely. Quick snapshots—where you whip out the camera, snap the shot, and quickly turn off the camera—destroy more photos than anything else. The camera needs a second or so to save the image to the card, something easily forgotten in the excitement of capturing the moment. Make sure the camera’s “Writing to Disk” light goes out before you turn off the camera or remove the card.

Formatting cards. Although Windows XP will gladly format your memory cards, don’t take it up on its offer, as it may make the card incompatible with your camera or other device. Format cards only in the device that will use them. And never remove the card during the formatting process.

Copy cards frequently. Today’s cameras can store hundreds of photos on a card the size of a dime. Don’t wait until it’s full before copying its contents to your PC. Instead, back up your card’s photos to your PC or laptop each day and start shooting with an empty card.

Static electricity. Avoid handling cards in dry, static-prone areas. One zap can kill the card and its contents.

X-rays. Although X-rays once damaged traditional film, they don’t affect memory cards. Don’t worry about running your memory cards (or digital cameras) through airport security checkpoints. If you’ll worry anyway, remove the camera’s card and drop it into your pocket before putting your camera on the conveyer belt.

Avoid water. Many cards are reasonably water-resistant. But to be safe, store extra cards (and your camera, for that matter) in a ziplock baggy when at the beach. And should water accidentally splash one of your cards, make sure it’s completely dry before using it. The innards of digital cameras or PDAs aren’t water-resistant.

Heat. Unlike traditional film, cards aren’t affected much by the heat. Try not to leave them on the dashboard, but if you do, they’ll probably still be okay. If you work in boiler rooms or build igloos, check out SanDisk’s (http://www.sandisk.com) Extreme III cards, designed to operate “at the limits of human physical endurance.”

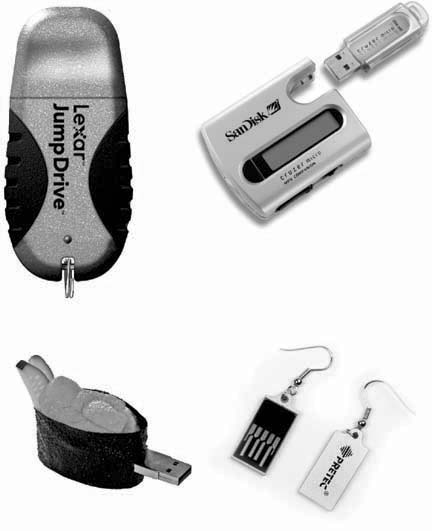

Take a memory card, stick it in a small enclosure, slap on a USB port, and you’ve created a USB drive—also called jump drives, thumb drives, keychain drives, flash drives, pocket drives, USB memory keys, and USB sticks. Windows XP calls them “USB Mass Storage Devices.” But whatever they’re called, the designers are going wild (see Figure B-5) with these new, portable ways to store your data.

The beauty of these little doodads is that they let you carry your most valuable data instead of leaving it inside your PC. That lets you work on any PC you come across just as well (or better) as on your own PC. The smallest ones carry much more data than a floppy drive; the larger ones hold more information than a CD.

USB drives provide a handy way to copy large files from one PC to another. Slip 20 MB of digital photos inside your flash drive, for instance, and you can show them on the PCs of everybody you visit.

Perhaps the two most famous USB drives are the iPod Shuffle and iPod Nano, which both combine flash memory with a built-in MP3 player. The iPod Shuffle arrived with storage options: either 512 MB or 1 GB of storage; the iPod Nano came on the scene in 2 GB or 4 GB variations. Capacity upgrades are sure to follow.

Figure B-5. USB drives let you bring your data with you in a wide variety of containers. Clockwise, from top left: You can wear Lexar’s traditional USB drive like a necklace or on a key ring. Lexar’s MP3 player can play songs from an inserted USB drive. Pretec’s USB earrings turn data into a fashion accessory. The Solid Alliance Sushi Disk looks cool, but rides rough in a pants pocket.

In the early days of computing, viruses spread mostly through floppy disks. Today, viruses primarily move through email, but USB drives could spread a new breed of USB-born viruses. To stay safe, look for a USB drive with a write-protect switch. Flip the switch, and PCs won’t be able to write anything—including viruses—to your drive and, subsequently, your PC. You can still run programs from the drive, or even copy programs and documents from it; the PC just can’t copy anything back.

If you must write information to your USB drive, be sure to scan the drive with a virus checker as soon as you insert it back into your own PC. It doesn’t take long, as the drives don’t come close to the size of your PC’s hard drive.

The latest drives offer fingerprint recognition, perfect for people carrying sensitive information.

To copy information between your drive and your PC, plug the USB drive into your PC’s USB port (Section 1.8.1). For speedier transfers, plug it into a USB 2.0 port rather than the USB 1.1 ports found on older PCs.

When you plug in the drive, Windows XP recognizes it as a USB Mass Storage Device—a portable hard drive, actually—and lets you copy information to and from the USB drive the same way you do with a hard drive.

USB drives work well for transporting important files, but they’re also great for carrying programs you can’t live without, so you run those programs on any PC. Not every program likes the small space of a USB drive, though; the best suited are small, run from a single file, and don’t require any installation.

Here’s a list of the most useful free and small programs that work well on USB drives. Some run straight from the drive; others you need to install onto a PC after you plug in your drive. Keeping any or all of these programs on your USB drive may keep you from hunting through a strange or understocked PC for its essential programs.

Abisource Word Processor (http://www.abisource.com/download). Free. This full-featured-but-tiny program handles the major word processor formats, and includes a spell checker, tables, and most of the tools found in the major players.

Ad-Aware SE Personal (http://www.lavasoft.com). Free. Ad-Aware searches out and deletes spyware on any PC you come across. Download the latest Reference file as well, and you can disinfect any PC without connecting to the Internet.

The Reference file, called defs.ref, lives on your PC’s C drive in the Program FilesLavasoftAd-aware folder. Copy that file and Ad-Aware SE Personal to the same folder on your USB drive. When you encounter a PC that needs a spyware checker, install Ad-Aware SE onto the PC from your USB drive; then copy the defs.ref file onto that PC’s C:Program FilesLavasoftAd-aware folder.

Adobe PDF Reader (http://www.foxitsoftware.com). Free. Foxit Software’s PDF reader lets you open Adobe Acrobat files, commonly used to store manuals and other documents, when a PC doesn’t have Adobe Reader installed. But while Adobe Reader consumes a whopping 20 MB, Foxit’s reader needs only 1 MB and runs as is, letting you skip installation.

Browser bookmarks. Free. Take your favorite Web sites with you on the road by “exporting” your browser’s (Section 15.1.1) bookmarks to a folder on your USB drive.

CDex (http://cdexos.sourceforge.net). Free. This small program rips CDs to MP3 files.

Cryptainer LE (http://www.cypherix.com). Free. Create hidden folders of up to 25 MB that encrypt your sensitive information (color copies of your passports when traveling, for instance, as well as medical records). Unlock them when you want to use the contents, and then lock them back up before you resume your travels.

Favorite photos. Priceless. Stick a photo of the spouse and kids on there, before they ask.

Favorite songs. Free. Be sure to put a few Desert Island MP3s onto your USB drive. Media Player will even convert them to the smaller WMA format, if you choose (Section 7.3.2).

Password Safe (http://passwordsafe.sourceforge.net). Free. Instead of juggling passwords, remember one password that unlocks this encrypted storage vault containing all your other passwords.

Web browser (http://portablefirefox.mozdev.org). Free. Spyware programs usually aim for Internet Explorer, so bypass it altogether when working on a strange PC. Portable FireFox lets the FireFox Web browser (Section 13.1.2) run from a USB drive.

XMPlay (http://www.un4seen.com). Free. XMPlay handles MP3, WMA, playlists, Internet Radio stations, and many audio formats Media Player can’t handle.

XnView (http://www.xnview.com). Free. This handy graphics conversion utility imports 400 graphics file formats and exports about 50.

Zero Assumption Digital Image Recovery (http://www.z-a-recovery.com). Free. This program recovers deleted or corrupted images from a memory card. Keeping the program on hand lets you retrieve accidentally deleted images from any nearby PC.

For more ideas, check out sites devoted to small, installation-free software: USB Apps (http://www.usbapps.com), TinyApps (http://www.tinyapps.org), and the Portable Freeware Collection (http://www.portablefreeware.com).

Memory cards and USB drives don’t require much troubleshooting. USB drives depend on the USB port to recognize them. If your PC can’t recognize your USB drive, try restarting your PC. If that fails, start running down the usual USB port troubleshooting rules (Section 1.8.2.1).

As for memory cards, the biggest problem comes when a card or thumb drive becomes corrupted, which usually happens when you remove it before the camera has time to store your latest photo. Even if your PC doesn’t recognize the photos or files, you can still save them with a recovery utility, discussed next.

When you delete photos from a memory card, they vanish, neatly bypassing the Recycle Bin. But before cursing too loudly, you may find that your pictures are still retrievable. That’s because memory cards store files using an index system, much like a library. When you delete the file, you’re deleting only that file’s reference from the index. The file remains on the disk until it’s overwritten with more photos.

That’s where recovery programs come in. Don’t use recovery-based programs marketed for hard drives, as memory cards store their information differently. Instead, reach for a recovery program designed specifically for memory cards. The programs analyze all parts of your entire card, even the unindexed portions. When they find a photo, they grab it and write it to your hard drive. Some programs even display all the deleted photos on your card, letting you pick and choose which ones to recover.

These programs will all examine every inch of your memory card for deleted programs and files, dredging up any past memories they find. Be prepared to wait on the edge of your seat for a little while, though, especially if you’re not piping all that information through a USB 2.0 port (Section 1.8.2.1).

Note

If you accidentally delete a photo, stop using the card immediately. Any new photos you take may overwrite the space holding your deleted photo.

Zero Assumption Digital Image Recovery (http://www.z-a-recovery.com). Free. Fire up this minimalist program, point it at the corrupt card in your card reader, and sit back while it recovers every digital photo still left on the card. It offers no options, but it works, and the price makes it a good first stop.

Data Rescue’s PhotoRescue (http://www.datarescue.com). $29. Download a trial version to see thumbnails of the photos it can rescue from your card. If you want to proceed, pay online for the unlock key, and then retrieve your photos on the spot.

PhotoOne Recovery (http://www.photoone.net). $24.95. The trial version lets you see and recover all lost images, but it slaps a message onto all but the first one. Once you pay online for the unlock key, you can retrieve them without the message.

Digital PhotoRescue Professional (http://www.objectrescue.com). $29.95. This grabs deleted photos from digital cameras, palmtops, and mobile phones; it supports just about every type of card on the market.

Photo Recovery (http://www.lc-tech.com). $39.95. This program, like the others, extracts deleted photos from a memory card.