The Big Picture: Creating Story Sequences

It’s now time to start refining your story by breaking it down into sequences. Beat boards give you the plot of the story. Sequences add subplots and give a film structure. They enable filmmakers to vary the pace of the storytelling, develop the characters’ personalities, and create realistic production timetables. Feature directors sometimes work as a team handling alternating sequences to help simplify the film’s production.

Feature animation stories are commonly divided into three acts defined by the beat boards:

![]() Act I. Introduction of the characters and their conflict.

Act I. Introduction of the characters and their conflict.

![]() Act II. Complication of the situation and a setback for the hero.

Act II. Complication of the situation and a setback for the hero.

![]() Act III. Resolution of the conflict.

Act III. Resolution of the conflict.

Each act is broken down into sequences by the Story Head and the director(s). Character development and story are fleshed out. More than one sequence may be used to illustrate the same story point. Storyboards will be redrawn and sequential order may be changed. Existing scripts will be rewritten to incorporate revisions made on the boards as a verbal story is transformed into a visual one.

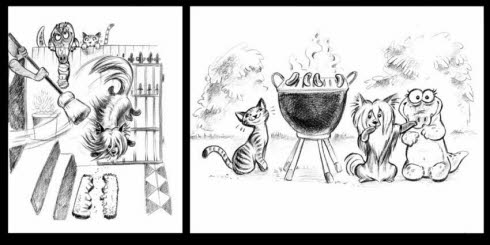

A sequence is a series of related scenes illustrating a story beat. A beat board is like a storybook. The important story points are conveyed in one or two illustrations. Several story points may be conveyed in one illustration. In animated film, several sequences may illustrate one story beat. Figure 13-1 would illustrate two different sequences if the story was produced as an animated film.

[Fig. 13-1] Beat boards and book illustrations both portray multiple actions in a single drawing. Illustration from Duffy and the Invisible Crocodile by Nancy Beiman, reproduced by permission of Patricia Bernard.

A sequence can take place in a single location (for example, in Grandma’s house).

A sequence can also be a series of scenes in different locations that illustrate the same story point (as in a dream sequence or action sequence). Animated sequences may go into production while other sections of the film are still being storyboarded. This is why it is desirable to solidly map out your main plot and character arcs in the beat board phase, so that your sequence details and subplots will fit within the larger structure. A short film may consist of only one sequence or be divided into one or two sequences depending on the story. Animation is produced like a patchwork quilt: small pieces make up the whole. It would be difficult if not impossible to complete a feature on time and on budget were it not divided into sequences.

Panels and Papers: A Word About Story Board Materials

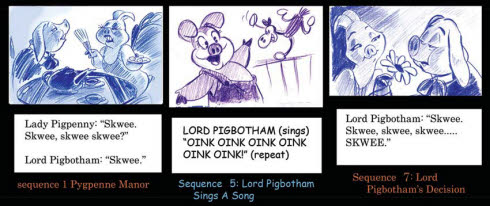

Television storyboards illustrate the script. There is no time in the schedule to allow the board artist to experiment with different approaches to the material. Everything has to be right the first time. Television and commercial boards are drawn comic-strip style with more than one panel on a page and camera moves indicated as shown in Figure 13-2, since the story and setting do not change much from script to final film.

[Fig. 13-2] A television animation storyboard has special panels for the picture, the action description, and the soundtrack. Several panels usually appear on one page. Reproduced by permission of Nelson Rhodes.

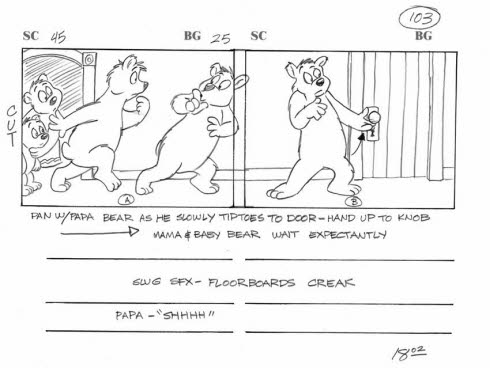

The storyboard is the ‘script’ of the feature film. Feature boards are drawn on separate panels since they may be re-pinned in different order during a turnover session. This cannot be done if more than one drawing appears on a page. Blank index cards work very well, but any blank pad may be used for storyboards in a pinch.

Feature board artists are allowed to rewrite or add new dialogue if it helps the scene. Dialogue is written on separate cards and pinned beneath the story panels. The dialogue can be shifted to a different character or cut if the action reads well without it. The modular approach works equally well with short personal films. Work with individual boards and sticky notes and plan for change. (There will always be changes!)

Acting Out: Structuring Your Sequences

A feature film is divided into acts that are divided into sequences. Some animated features are composed of sequences that are actually discrete short films based on a common theme. Examples of this type of film include Walt Disney’s FANTASIA, Bruno Bozzetto’s ALLEGRO NON TROPPO, and Bill Plympton’s THE TUNE. The omnibus film eliminates the need for a continuing storyline.

Different moods, characters, and techniques may be used in one film. Each short film will contain its own sequential structure. Film titles will sometimes have a separate sequence number if animation begins before or plays under the main credits. Here are fictional sequences and numbers from Act I of the animated feature THE STRANGE CASE OF THE THREE BEARS. All sequences in an animated feature film are given descriptive names as well as numbers. The names are written down in sequential order before storyboarding begins. Naming a sequence gives the director and story artist a description of its action. This enables them to see the film’s structure and pace the story without having to view all of the storyboards simultaneously.

Sequence numbers will change if they are edited into the film in different order than originally planned. Decimal points are added if a new sequence is inserted between two older ones. A sequence may be renumbered (with its “OLD” number retained in parentheses) but its name will remain consistent throughout the production so as to avoid confusion. The decimal point in Sequence 1.5 indicates that it was added between Sequences 1 and 2 at a later date. The ”OLD” number is retained since it is possible that Sequence 1.5 could be put back in its original order and renumbered as Sequence 4.1. Sequence 4.5 was also added after the main sequences were numbered. Note that Sequences 2 and 7 are O.O.P., or “out of picture.” Sequences are not renumbered when one is edited out. The finished film will cut from Sequence 1.5 to Sequence 3 and from Sequence 6 to Sequence 8.

Do these sequence names describe the action? How many sequences illustrate each of the story beats depicted in Figures 12-4 in Chapter 12? Which sequences might be cut without harming the story?

Production A113: “THE STRANGE CASE OF THE THREE BEARS”

ACT I:

Sequence 1: The Bears’ Bad Breakfast

Sequence 1.5: Bearly Remembered (Old Sequence 4.1)

Sequence 2: OOP

Sequence 3: Goldilocks Breaks into the House

Sequence 3.5: Goldilocks’ Golden Memories

Sequence 4: The Chairs Are There

Sequence 4.5 Jolly Happy Bear Song

Sequence 5: Bedtime for Goldilocks

Sequence 6: The Bears Head Home (Jolly Happy Bear Song II)

Sequence 7: OOP

Sequence 8: The Creep Sleeping in My Bed

Sequence 9: Goldilocks Escapes

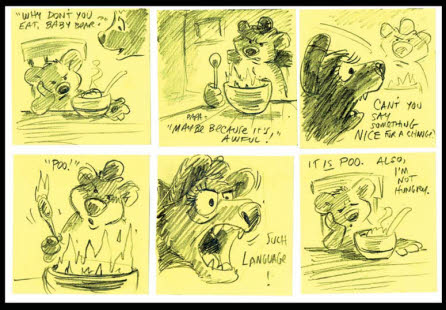

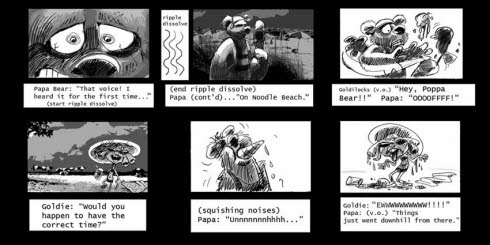

Figure 13-3 illustrates Sequence 1, “The Bears’ Bad Breakfast,” which introduces the main characters and their conflicts. The action in the sequence takes place at a specific time and place with a set group of characters and illustrates one idea. It introduces our heroes and is therefore essential to the story.

[Fig. 13-3] These thumbnails rough out some of the action from Act I, Sequence 1 of THE STRANGE CASE OF THE THREE BEARS.

Figure 13-4 is an excerpt from Act I, Sequence 1.5, “Bearly Remembered,” where Papa Bear has a flashback to his troubled past. This is an example of a subplot that leads to character conflict—Papa Bear and Goldilocks have met before! The action takes place in a new location and introduces a new character. The decimal point indicates that the flashback sequence was added to the story after the main sequences were boarded and its old number, 4.1, tells us that it formerly appeared at a later point in the film.

[Fig. 13-4] Sequence 1.5 is a flashback that takes place in more than one location but all drawings illustrate the same story point. Backgrounds can be drawn on the first panel of each scene and eliminated once the character relationships are established.

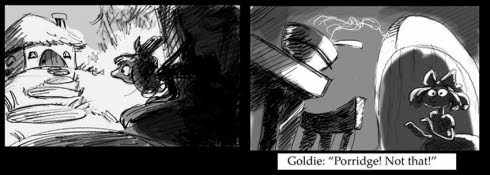

Sequence 2 is out of the picture (O.O.P.). Sequence 3 takes place in the same location as Sequence 1. A different sequence number and name is used since the action takes place later in the film and a new story idea is introduced.

[Fig. 13-5] Sequence 3 takes place in the same location as Sequence 1. The same backgrounds and props will be used for both sequences.

Simple descriptive names indicate each sequence’s content and story point. A sequence’s name is usually a clever pun. This makes the name easy to remember even if the memory creates the occasional shudder.

It does not matter which type of names you choose for your sequences, since they will never appear in the finished production. The names simply indicate what the sequences are about. Identifying each sequence by name and number will be very helpful to you whether you are on a long production containing two dozen of them, or a short one with three or four. Sequences often go into production out of sequential order. The names and numbers keep artistic materials organized and keep the crew informed about the story’s twists and turns. Sequences are prioritized with an A-B-C system since some might be edited out after storyboards are completed (there are two OOP sequences in the outline for the Three Bears feature).

A-B-C-Sequences: Prioritizing the Action

Each sequence is assigned a letter “A,” “B,” or “C” to indicate its importance to the story. The “A” sequences are essential to the story and often have the most extensive and complex action. They are boarded first. The “B” sequences are still important but are less difficult to board and animate. The “B” sequences may go into production before the “A” sequences gets out of pre-production. The “C” sequences may be edited out without damaging the story. “C” sequences are put into production last so that they may be cut from the film if time or money runs out. The same prioritization is used for scenes within the sequences.

KNOW YOUR A-B-C’s

- An “A” scene/sequence is an essential story point that must be in the film and cannot be eliminated.

- A “B” scene/sequence is also important, but it can be shortened or restaged if time and budget require it.

- A “C” scene/sequence is one that contains material that may be amusing but not essential. It can be cut without compromising the story.

Label your sequences and scenes and work on them in order of importance. Prioritization ensures that the important story points are finished. Inessential sequences may be cut so that the film can be completed on time.

Character relationships are set up in Act 1 of the feature-length story. Act 2 (conflict), which opens with Sequence 10, provides an opposing figure (or villainess) as Goldilocks and her crony Little Red Riding Hood team up to blackmail Papa Bear, who has been eating Baby Bear’s just-right porridge for years and blaming the theft on Goldilocks. Act 3 (climax and resolution) shows the Bears’ climactic struggle to defeat the Goldilocks gang. Papa admits to his faults so that Justice may triumph. When it does, they all go out for a pizza. Please note: There is no formula for animated film stories. Use this structure as a guideline only!

A ‘big picture’ view of the film will help you develop the hero’s character arc.

A character arc is created when the story’s action changes the hero in some way by the end of the film. Character arcs can be described in the original outline for the film. In this book’s version of THE THREE BEARS, Papa Bear blames Goldilocks for the theft of Baby Bear’s porridge when he is the one who’s been secretly eating it. At the end of the picture, Papa Bear admits his character weakness and overcomes his fears to defeat the menacing Goldilocks. (Mama Bear probably learns to be a better cook!)

Characters that do not grow and change as the story progresses tend to be flat, onenote creations with little depth, as depicted in Figure 13-6.

[Fig. 13-6] A hero without a character arc remains unchanged from start to finish. This may not keep the viewer interested in his story.

Breaking your story down into sequences helps you analyze the rhythm of your film and develop the characters’ personalities over time. Storyboards for large portions of a feature film (and all of a short film) may be viewed simultaneously. Changes can be made on the spot. The original story structure may need revision if several action sequences and song sequences appear consecutively or too many sequences are set in the same location. The modular storyboards make this relatively simple to do.

Each storyboard artist must be familiar with the story outline and know how the characters develop. On longer film projects the story staff periodically views work-in-progress on boards or on reels, so that story points and gags are not inadvertently repeated. If the artist does not know what happens before and after his/her sequence, the character’s performance may be inconsistent throughout the picture. A rather exaggerated example appears in the next figure.

[Fig. 13-7] Story artists sometimes work in isolation. It’s very important to know what happens before and after their sequence so that it fits into the context of the picture.

Feature animators often thumbnail character actions and staging for all the scenes in a sequence at once so that the acting remains consistent throughout even if the scenes are animated out of order. If the animator has an understanding of the story and the character, it is possible to come back to a sequence put on hold months earlier without making it obvious that portions of it were animated at different times. My animation of the Fates in HERCULES was put on hold after a few scenes were completed while another part of the sequence underwent storyboard revisions. I was able to keep the ‘actresses’ in character when I returned to the Fates sequence seven months later because I had first thumbnailed the action for every scene after viewing the story reel and the storyboards for the sequences preceding and following the Fates. I was able to tailor my animation so that it fit into the film’s context.

The script or outline will be rewritten to incorporate modifications made on the storyboard as sequences are developed. Walt Disney Studio story man Floyd Norman describes how THE JUNGLE BOOK changed between outline and storyboard:

“The guys [in the story department] would just kick around a lot of ideas. Larry Clemmons was our official writer. What Larry would do was put together an outline of the way a sequence might “play.” Then this rough script outline was handed out to the story artists who would take it and embellish it. Everything was wide open. We would try anything. It wasn’t structured and no one was saying “You can’t do this or that.” [Vance Gerry and I] were given Mowgli and the snake [sequence] and so we started working out some gag ideas. The first version of THE JUNGLE BOOK as envisioned by Bill Peet was a much darker film. This was not to Walt Disney’s taste. We really just took the story and redid it. When we showed it to Walt he liked it and said, “Do more with this.” He had the Sherman brothers write a song (“Trust in Me”). People still talk about it. We had no idea the film was that good! You never know. I guess the audience tells you.”

(Interview with Nancy Beiman, August 29, 2000)

Characters in animated film, including incidentals, receive names for precisely the same reason that sequences do. If a scene contains multiple characters it is far easier to direct action on “Julie and Steve” than “the pink fish with the blue eyes” and “the octopus with the bowtie and moustache” since there may be more than one moustached, bowtie-wearing octopus in a scene, as shown in Figure 13-8.

[Fig. 13-8] Animated characters have names so that it is easier to direct the action in scenes involving more than one character. “Julie and Steve” may never have their names mentioned in the film. The incidental characters in the scene are also named.

An animated film will usually have story development and story revisions occurring simultaneously. Breaking the picture into sequences helps keep the characters, the story, and the filmmaker’s head pointed in the right direction.

Now that you have named and numbered your sequences and characters and determined your characters’ arcs you are ready to stick in your thumbs—thumbnail drawings, that is—to stage the action and acting for each sequence. But things are going to get rough!