First Catch Your Rabbit: Creating Concepts and Characters

There is a famous old cookbook recipe for stewed rabbit. The first sentence of the recipe gets right to the point. It reads: “First, catch your rabbit.”

How do you “catch the rabbit” and create original characters and stories? Where do ideas for original stories and characters come from?

A story recipe depends on the freshness of the ingredients, the quality of the preparation, and the skills of the creator.

The first two ingredients— Character and Conflict—develop simultaneously. Both must be established at the beginning of your story and, like well-written newspaper headlines, they will immediately grab the reader’s attention. A quick search through several online news sites yielded the following unusual “human interest” stories:

Robot Runs On Flies and Sewage

Berlin Bear Steals Bicycle, Attempts Breakout From Zoo

Boozy Bear Plunders Camper’s Beer

Zombie Worms Found Off Sweden

These actual news items already sound like story lines for animated cartoons. All of the stories have one thing in common: they convey a visual image.

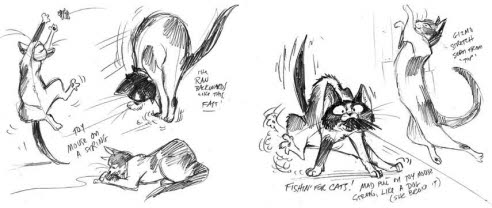

[Fig. 1-2] Sketches based on online news reports from the BBC, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and Reuters News Service.

Some of these headlines leave the reader wanting to know what happened next— (Where was the bear going to go with the bicycle?)—or empathizing with a character’s situation—(What kind of self-esteem does a fly-eating robot have?). An animated story line may grow from a grain of truth.

Animation pre-production is called development for a reason. One definition of development is “the act of improving by expanding or enlarging or refining.” The story and characters grow and change during pre-production from simple ideas to the complex, structured, visual story.

The next ingredient in the story stew is imagination. Animation is not reality and it is at its best when it portrays things that could possibly happen. The seed of reality provides the viewer with a point of identification and then germinates into a fantastic story.

Feature animation often does not start with a written script. The germ of the story can be conveyed in a short outline or treatment. The characters and plot twists are then developed visually. Stories can change dramatically when they are boarded. Scripts are not finalized until the latter stages of preproduction so that they may incorporate new material created on the storyboard.

Old-time animation story men referred to a story as the “clothesline” on which they would “hang” gags and character development. The shorter film develops more quickly than a feature since it has less time to tell the story. You should be able to convey a story idea in a few short, direct sentences. If you are unable to do this, the idea needs work.

Here are some stories from existing animated films retold as newspaper headlines. Can you identify the films?

Flying Elephant Rescues Mother, Saves Circus

Rabbit Takes Revenge on Hunter

Dalmatian Puppies Missing, Possible Victims of Fur Coat Ring

Heroic Ogre Saves Princess from Dragon, Removes Tyrannical King

Exercise: Write three more ‘headlines’ based on existing animated films. Does each headline convey a visual image of the story?

This technique is actually used in animation and live-action pre-production under another name.

The log line (a brief description of the story and conflict) is the foundation for the story edifice. Walt Disney said that an animated film’s story was constructed “like building a building with building blocks. Our building blocks would be ‘personalities’” (Ken Anderson interviewed by Nancy Beiman, 1979.) The entire interview appears in Appendix 3. Log Lines are discussed in Chapter 4.

Linear and Non-linear Storytelling

A linear story progresses from A (beginning) to B (middle) to C (resolution) in sequential time. A situation is established at the start, a complication arises in the middle section, and resolution of some kind comes at the end. Most feature-length animation works in linear format.

Linear stories can also work in reverse, as seen in Piet Kroon’s short film T.R.A.N.S.I.T. The film opens as a man is immigrating to Argentina after a murder. It progresses into the past to show how the characters’ relationships made this outcome inevitable.

Non-linear animation concentrates on creating an effect or mood rather than telling a carefully plotted story. Many short experimental films fall into this category. WAKING LIFE is a rare example of a feature-length non-linear story. It follows dreamlike logic that evolves over time instead of proceeding toward a specific goal.

Linear and non-linear stories will both require extensive preproduction work, though non-linear stories might not rely as much on character development to achieve their effect. If you are planning to make a non-linear film conveying moods or emotions, research different artistic styles, color, sound, music, and effects that will create the desired impressions in the viewer’s mind.

You may not wish to make an autobiographical film, but elements from your life can add a dash of reality that strengthens the situation and characters. True-life adventures will be discussed in detail in Chapter 2.

Setting Limitations and Finding Liberation

“Do anything you like” is the hardest assignment I ever had. Limitations must be set so that the story doesn’t run off in all directions.

My students’ first character design assignment is to assemble a “found character” based on a series of words pulled out of an envelope. They are provided with a character name, sex, species, age, and time period, but no story context. Their second assignment has them changing a human character into an animal in three drawings. The midpoint is sometimes more interesting than the final!

[Fig. 1-3] A 1900’s gangster turns into an owl. Character design assignment reproduced by permission of William Robinson.

For their third assignment students create a pair of characters that contrast Large with Small. No other information is provided. The fourth assignment provides their first story context: characters must illustrate a simple story line taken from a nursery rhyme.

My students invariably find the ‘found character’ and ‘large versus small’ assignments more difficult than the nursery rhyme . The creation of the nursery rhyme characters is considered easier since the story context provides a guideline for the character’s appearance and personality. By narrowing the focus (using a pre-existing story, names, and descriptions as a framework), a set of limitations are created that become “liberations.” Characters are easier to design when placed within a story context.

[Fig. 1-4] “Jack and Mrs. Sprat” (nursery rhyme). Character design assignment reproduced by permission of Jim Downer.

A character created in isolation as in the other three exercises is just a design. It is not a personality. The human-to-animal assignment infuses some of the human’s quality into the animal, which is the beginning of personality development. The story context in the fourth assignment is the crucial ingredient in our recipe. The story will influence the character’s personality and appearance and the character’s personality will influence the story development. Which comes first, the chicken or the egg, character or story? Both elements are equally important.

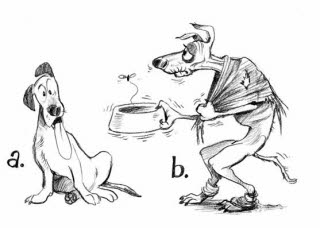

Figure 1-5 shows designs for (a) an ordinary dog and (b) the dog from this old nursery rhyme:

Old Mother Hubbard went to the cupboard, to get her poor dog a bone.

But when she got there, the cupboard was bare, and so the poor dog had none.

[Fig. 1.5] The dog in (a) is “just a mutt” working outside of any story context. The second dog (b) shows a particular personality, age, and attitude.

The second illustration portrays a stronger character than the first since there is more visual information to set the animal’s personality and appearance. The words “old” and “poor” in the nursery rhyme lead to a visual interpretation so that we see that the dog is old and poor before we hear it. Dialogue should support the visual elements of an animated film.

Shopping for Story: Creating Lists

A story can be created by chance or by deliberation, or you can write a shopping list for the ingredients!

Free association can get the creative juices flowing. Use words that create visual images. Draw four columns on a sheet of lined paper and begin. It helps to do this exercise with another person since you can “bounce” ideas off one another and build on each other’s word associations.

The first column is a list of characters. Can they be animal, vegetable, or mineral? Are they organic or inorganic? You are not restricted by what exists in the real world. Put that animation magic to work. Any one or any thing is a possible animated character. Describe them in one or two words. Do not write lengthy biographies or back stories.

Can they be human or animal? Are they four legged or two legged? Could a character be a combination of organic and inorganic objects? Imaginary creatures are the hardest ones to do, and so if you wish to design one make separate lists of words that describe the creature’s abilities and appearance. (1) Can it fly and swim? Does it tap dance and sing opera? (2) Does it have feathers, fur, scales, or all of the above? Write down

as many variations as you can think of. At this point, everything is possible. The words “no” and “can’t” are not in your vocabulary.

List all of your ideas no matter how odd they may seem. Do not throw anything out at this stage. Build on earlier suggestions by free-association. Be creative and have fun. But characters do not work well in isolation. They must be put into some sort of context.

Where does this story take place?

Write a list of possible locations in Column Two. These can be fanciful and vary greatly in scale. One major feature film, OSMOSIS JONES, was staged entirely on the molecular level inside a human body.

Can you place your characters inside a refrigerator, in France, on a dog’s back, inside a sock drawer, under the bed, on the moon, or under the ocean? See if one location leads you to think of another, or of characters that might populate it.

Make a list of situations and occupations in the third column. Birthdays, weddings, funerals, jail breaks, alien abductions, trips to the dentist, preparation of a meal, a dance, a wedding, thieves, shepherds, and insurance salesmen are all fair game.

Next, list possible conflicts in the fourth column. What weaknesses do these characters have? Do their parents approve of what they are doing? Is one character in danger? Is it searching for something? Now, mix and match words from the character, location, situation, and conflict lists to form short sentences. See which combinations suggest images or stories. You may be inspired by a single word or use material from all four lists. As you do this, a story may start to build itself. Draw rough sketches and thumbnails to illustrate ideas suggested by the word combinations. The following story outline was assembled from the four sample lists:

Characters: Vegetables (tomatoes, onions, corn, and melons).

Location: The refrigerator.

Occupation: Thief. Situation: A group of vegetable criminals decide to make a jail break from the refrigerator before they are put into a stew.

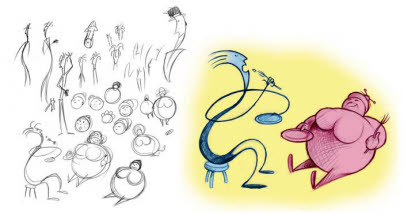

Conflict: They are on Death Row (in the fridge) since they have all gone “bad.” The cook is their executioner. Figure 1-6 depicts possible “bad vegetable” characters.

[Fig. 1-6] When vegetables go bad.

Draw thumbnails of characters and situations on a yellow-lined pad. Do not use an eraser and do not throw away any of the drawings. Work rough and don’t worry about design details at this time. Final character design is created at a later stage. Don’t just use one character or explore one story avenue; we’re in blue sky territory so anything goes. It is okay to use color when thumbnailing rough character designs, but keep the story sketches in black and white for now.

”Normal” characters can become very interesting when placed in unfamiliar context. This time we will work with the word “wedding” from the ‘situation’ list. What if the groom and bride are a shepherd and shepherdess? Perhaps the wedding guests could be sheep and sheepdogs as shown in Figure 1-7.

[Fig. 1-7] What is right with this picture? The shepherds are not as interesting as the animals. The most interesting characters should tell your stories.

Some comic potential is lost since the shepherds do not seem to be as out of place in this setting as the animals do. The animals are, frankly, more interesting than the people.

A story should always be told by the most interesting characters. The animals are more interesting than the shepherds in this story since they appear outside their usual context. What if the animals became the main characters? That’s an improvement since humanized animal characters play to the strong points of the animation medium. Could the sheep get married instead of the shepherds? What sort of characters might interact with them? Could the wedding guests be shepherds, sheepdogs, and wolves? Do the animals behave like humans? How does this story point affect the design of the film and the characters? Can sheep and wolves be used to represent certain kinds of human personalities? Might the animals be caricatures of human relatives and character types? Recognizable human traits create sympathy for fantastic characters. It is important to make your main characters more interesting than the secondary characters. If the hero’s story does not attract and maintain your interest, perhaps you are working with the wrong character. Figure 1-8 shows a more novel staging of the wedding.

[Fig. 1-8] Using animal characters to suggest human traits and foibles is as old as Aesop.

The wedding story may still not be working with the most interesting characters.

I call the next part of the questionnaire the “What Ifs?” What if the loving couple is from two different species? What if they are a star-crossed sheep and a wolf? What if a sheep married a sheepdog? What stories and conflicts might be created by these contrasting characters?

The characters’ appearances are just the beginning. Their actions and personalities will develop from your observations and caricatures of real life.

[Fig 1-9] Contrasts between characters can create a story. Try different combinations of scale and species and work with the most interesting one.

Nothing Is Normal: Researching Action

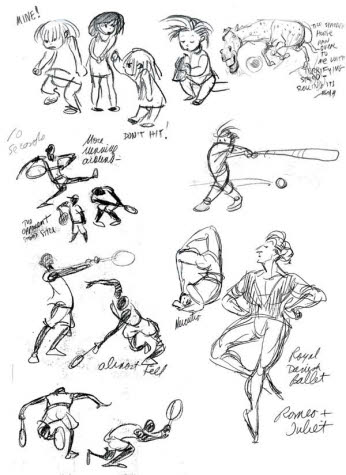

Your most important research tool is a sketchbook. You should draw in the sketchbook every day. Visit zoos, playgrounds, basketball games, even the laundromat. Draw rough impressions of moving figures, not portraits or immobile poses. Write notes next to the drawing that describe the subject’s attitude. Sketch quick poses that express characters in motion. Figure 1-10 shows a page of gesture drawings from my sketchbooks with some explanatory notes.

[Fig. 1-10] A page assembled from my sketchbooks. Notes are sometimes added to describe the subject’s emotional state. Some of these sketches were used as reference for later character designs.

Think of gesture drawing as reference material for acting, character, and story.

Gesture drawings of humans and animals in action will help you create stronger poses for your animated characters and make you a better actor. Working from life is recommended but dance and music videos or action films can also be used as ‘models’ since these films portray action that is more intense than normal. Run the tapes or discs in slow motion, watch the actors’ progressive movements, and draw as if the model was in the room instead of onscreen. The films of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton provide particularly good comic and dramatic action reference. Avoid drawing from photographs since this will usually make your drawing appear “flat.” Your subject should be moving in the third and fourth dimensions.

Once you start observing people and animals you will see that no one and nothing is ever ‘ordinary’. Everyone moves slightly differently from one another. People and animals also move differently when they are in different moods. These varying attitudes should be taken into account when creating model sheets and storyboards for your characters since they will influence the animation that comes afterward.

Pets are great subjects for gesture drawing because they never stand still! Don’t try to draw formal portraits. Draw them while they are playing or moving around. You will know their characteristic gestures and attitudes from experience. Work quickly and never scratch out a drawing—just draw another sketch on the same page if you are not satisfied with the first one. You’ll soon be able to do it from memory.

[Fig. 1-11] My cat Gizmo, drawn from memory. She moved far too fast to ‘pose’ for any of the pictures. I drew rough sketches of her movements after she finished them. Gesture drawing is an impression of movement, not actuality.

All Thumbs: Quick sketches and Thumbnails

Character designs and storyboards both start out as rough and simple thumbnails.

Thumbnails are drawn thoughts. These small sketches, combined with brief notes, capture ideas for a story or character so that the memory is not lost. Thumbnails can be worked up into a finished drawing at a later time.

Always work rough before going clean. Do not render or model final drawings at this stage of development. Draw a new thumbnail if you think you can stage something better. Thumbnails allow you to change the drawings and your mind.

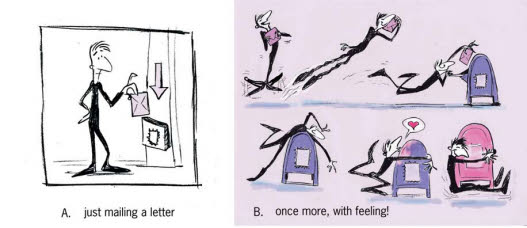

Figure 1-12 shows two versions of a simple action originally described by animator Frank Thomas. The first sketch (a) only shows the basic action, but (b) is a series of thumbnails that convey the character’s attitude and personality along with the action. The thumbnails also tell a story. Is it possible to depict the action in (b) with only one sketch? (Try it for yourself using this character or one of your own designs.)

[Fig. 1-12] Frank Thomas’ example: (a) A man mails a letter, or (b) A man mails a letter to someone he loves. The emotional state of the character affects every move he makes. Thumbnail drawings portray different stages of the animated action.

Reality Is Overrated

Use reality as inspiration when creating animated characters and stories but adapt it, don’t copy it. Real life provides basic reference material. Animation improves on it.

Animated characters should be believable, not realistic. The laws of gravity and physics may change in animation. A character can float on a cushion of emotional bliss as shown in Figure 1-12b, or change its physical shape, color, or size when its mood varies. Visual hyperbole, caricature, and stylized action are much more interesting than literal renditions of natural motion.

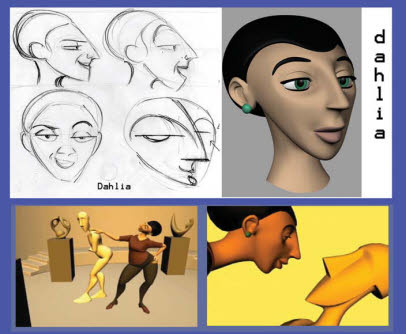

Human characters are the hardest ones to do. It is difficult to portray “realistic” humans convincingly in animation because everyone sees a human face every day in the bathroom mirror and knows how to make it move. Inaccuracies and deviations from the norm will be obvious. (There’s more “wiggle room” in animal design since you don’t see a lion in the bathroom mirror every day.) Computer-generated imagery (CGI) animation sometimes tries too hard for literalism, which can lead to the creation of human characters with staring eyes and doll-like features that (ironically) appear to lack all life and animation. This is known as the ‘cryogenic effect’. Let us compare the design of two human heads. The CGI head in Figure 1-13 was an isolated exercise created outside of a story context. One drawing of a front view and one side view was imported into a computer program. The artist did not first analyze and sketch its planes or expressions or base the design on caricatured reality. The resulting head is neither realistic nor believable.

[Fig. 1-13] A Cryogenic Head.

[Fig. 1-14] Stylized human characters. Reproduced by permission of Nathaniel Hubbell.

The stylized CGI character in Figure 1-14 was based on caricatures by the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias rather than photorealistic references. The story required human characters with expressive features and mobile bodies. Dahlia’s caricatured and stylized features create appeal and interest in her design. Rough construction models of her head and body were drawn after the design was finalized and before computer modeling began. Action sketches of Dahlia’s facial expressions and body movements served as guidelines when she was modeled, rigged, and textured.

The action took place in an art museum where human characters interacted with living artwork. Each proportion of Dahlia’s face and body was carefully planned. She and her cubist dance partner were designed at the same time so that they worked well together. Animation is hyper-reality. It has to go a little farther than live action to create the illusion of life.

Past and Present: Researching Settings and Costumes

“Back in the day,” animation designers and cartoonists kept a “morgue” of reference pictures. Mine was an enormous black filing cabinet stuffed with files labeled, “Fashion,” “Celebrities,” “Wild Animals, Africa,” “Pets,” “Children,” and so on.

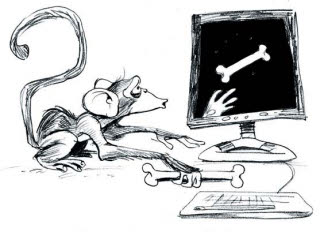

The Internet is the world’s greatest reference library if you already know what you are looking for. It is a good idea to familiarize yourself with the art and mores of other times and places if you are serious about working as a story artist or character designer. Knowledge and research will help you to find the right reference materials for a film set in a particular period. This is the way to avoid anachronisms (items used out of their context in time) unless they are necessary for your story. Figure 1-15 is an example of an anachronism.

[Fig. 1-15] A computer is an anachronism in the Stone Age.

Production development incorporates all of the arts and a good chunk of life into its matrix. Each project presents you with an opportunity to learn about different cultures, historic eras, and characters. The development artist has the enviable task of being paid to learn. Researching a film is a fascinating and educational experience.

A story artist or character designer will want to learn a little bit about a lot of things, including, but not limited to: dance; history (world and national); popular and high-culture music, art, film, and literature; geography; anatomy (human and animal); zoology and biology; theatre; color theory; industrial and product design; astronomy; acting; sports; botany; fashion design and fashion history by decade and by country; child behavior; national customs and landmarks; fantasy in art and literature; caricature; architecture; archaeology; folktales; psychology; and any hobbies you might care to add. As we shall see in Chapter 3, it also helps to know something about yourself.

The aspiring story artist should understand film language, learn how signature styles of filmmaking evolved over time, and be familiar with live-action and animated films from many countries and eras. Most importantly: the story artist must know the difference between feature and short animation storyboards and the boards used for comic strips, television, and live-action films. These differences are discussed in Chapter 3.