Present Tense: Creating a Performance on Storyboards

“Have a very good reason for everything you do.”

—Sir Laurence Olivier

“Writing is 1 percent inspiration, and 99 percent elimination.”

—Louise Brooks

You are now ready to begin creating in-depth storyboards that flesh out the acting and actions of the characters. If you are working on your own film, you will have your outline, beat boards, rough character models, and atmosphere sketches completed by this stage and your sequences should be clearly defined.

If you are on a professional production you will most likely be working in a totally different system. A television storyboard artist will be handed a model pack, or “Bible,” with all characters, props, and backgrounds already designed. Each artist will be assigned a script for a sequence or for the entire show, and given a deadline to finish boarding it. All characters must be drawn accurately or on model and camera moves and background detail must be clearly indicated on the boards.

Feature storyboard artists work as a team or crew under a story head with each artist handling one sequence of a film or working with a few pages of a script or outline that was written in advance. The story head works out the sequences and beats with the film’s directors, creates the beat boards, and decides which artists will board which sequences. Atmospheric sketches and rough character designs may not yet exist. Each artist will work separately from the others but will have some idea of what the rest of the picture is about so that their sequence fits into the story. The story head reviews and approves the thumbnails for each sequence and the artists then draw rough boards that are presented to the directors in a first pass. If this goes well, the rough boards may be reworked and detail added, turning them into presentation boards. It is far more likely that they will go through many rough revisions before they are finalized. Feature films spend an average of two years in development. Some have taken longer.

[Fig. 15-1] Feature films can take a long time to complete if their story problems are not worked out at the beginning of production. Reproduced from Son of Faster Cheaper by permission of Floyd Norman.

Commercial animated films were not always produced this way. In the early days, the story men and women were the writers of the picture. They drew thumbnails of the characters and the staging, wrote story outlines, and then worked their thumbnails up into finished boards. The writers and directors at the Warner Brothers cartoon studio often worked in groups and bounced ideas off one another. Writers such as Mike Maltese and Tedd Pierce would eventually put the witty dialogue for Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck directly on the storyboards. The final script was written out for the voice artists to read during recording sessions. Walt Disney Studio story man and art director Ken Anderson stated that he would write his own outlines for feature films, sketching the character designs at the same time, and that the storyboard always took precedence over the script. In the instances where a feature began with a writer’s treatment, it was not uncommon to have the story change 180 degrees by the time the storyboards were completed. (A transcript of my interview with Ken Anderson is included in Appendix 3.)

The Story Head on a modern feature film will act as a “third director,” in the words of story head and director Brenda Chapman. The story head has specific responsibilities: he or she will focus entirely on the story, while the directors are responsible for every aspect of the film. The story ideally is a collaborative process, with the writers working directly with the artists and the directors having final approval.

A story head will pick their crew of artists, give them their assignments or handouts, and ensure that the artists function as a unit. He or she keeps track of each sequence and notifies the crew of developments and changes, sometimes on a daily basis. At times the story head will provide rough thumbnails for the storyboard artist to use, along with a description of the characters’ attitudes and acting. Most of the time the artists are given free rein to interpret the material in their own way. Individual artists will be assigned to sequences that play to their particular strength. Some will excel at action scenes while others might be better ‘cast’ on comedy scenes. Story artists will write or replace dialogue and add “business” that helps flesh out the written material. They may revise the script and create or delete characters if the story seems to require it. Freedom to do this will depend on the production, but the better films I’ve worked on welcomed constructive change, or plus-ing, at this stage of development. Scripts that are set in stone tend to produce weaker films.

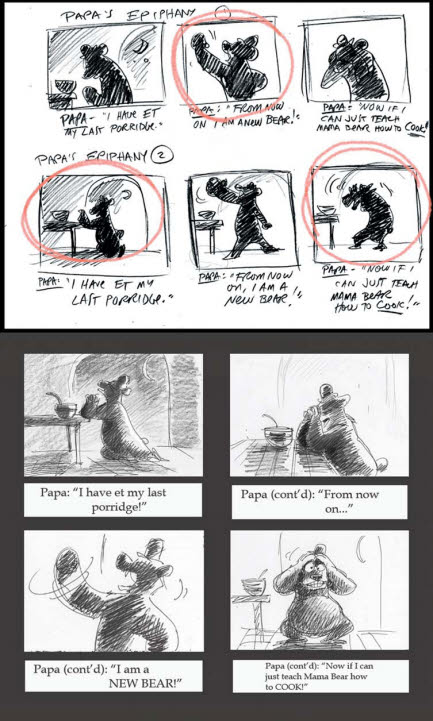

When a story man or woman receives an assignment from the Story Head, he or she will first rough out thumbnails to experiment with staging. In Figure 15-2, two different sets of thumbnails have been drawn up for a short sequence. One version is staged in medium shot and the other is staged entirely in close-up. The dialogue is written under each frame. The two interpretations might be combined in the final film.

[Fig. 15-2] The sequence is thumbnailed in two alternate views. The final may use elements from both versions.

The story head will review the thumbnails with the storyboard artist. If the story head approves the roughs, a rough storyboard will be created for the director(s). This board will be pitched in a first pass and changes will be suggested in a turnover session. The process will be repeated until the story is acceptable to the directors, at which time the boards may be left rough or highly-rendered presentation boards may be drawn to replace them, depending on the production and the people involved. Some directors will use extremely rough storyboards and others might require more polished examples for the story reel. Storyboard pitches are discussed in detail in Chapter 18 and the story reel is described in Chapter 19.

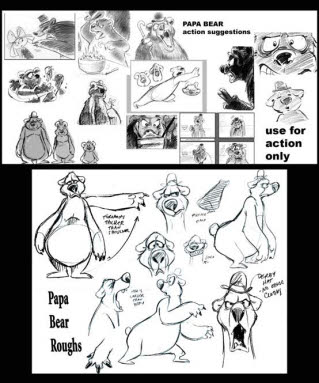

If the characters have not yet been designed, rough placeholder characters as shown in Chapter 10, Figure 10-1, are used on the boards. The storyboard artist will have a major influence on the final appearance of the characters since they are drawing the acting that will be required in the film. Storyboard drawings that best convey the characters’ personality and typical actions are frequently copied and pasted up into model suggestion or action-model-only sheets. Character designers and animators receive copies of these suggestions as a reference guide. The drawings and designs will be refined and standardized as the rough model sheets are created but the action sheets can be used for acting reference by the animators all through the picture.

[Fig. 15-3] Storyboard sketches are selected for expressiveness and pasted up into an action-model-only sheet. This may be used as reference by the animator all through the picture since it conveys Papa Bear’s acting range very well. The model sheets will try to retain the spirit of the storyboard drawings even if the character’s final design bears little resemblance to the storyboard sketches.

Portions of the script will be rewritten if the material is not working successfully on the storyboards. If there is a major story change, the art direction and character design may also have to be reworked.

A good story artist is open to change, since this is the one thing that is guaranteed to happen on all productions. The story man or woman has to know what to change so that the story baby is not thrown out with the bathwater. Sequences will be deleted if they no longer work, and will be replaced by new ones that may be replaced in turn. It is essential that the storyboard artist not take the reworking or deletion of his or her art personally. Storyboard is about change. There is nothing wrong with changing your drawings. It’s highly unlikely that any storyboard will get it right the first time and it’s not uncommon to have to redo entire boards if the story artist’s vision does not coincide with that of the directors.

An original story is hardest to storyboard. Fairy tales have a basic story that is already worked out; original stories must find their own way. When the story is not yet set, some sequences will be experimental. Storyboard artists will thumbnail many rough sequences and much of this material will go unused in the final film. But, as with all animated work, it is best to change the story while the film is still in development rather than try to make repairs later on. Changes to animated films become more expensive the later they occur in production. Some films have had their entire stories changed when they were well into animation. Years of work and a good portion of the budget were wasted. If the story is well conceived and develops in a believable fashion, much heartache and waste may be avoided. But it

is essential for the directors, producers, and story head to agree on what they are trying to say.

It is a common practice to hire “name” actors to do the character voices, caricature them in the character designs, and assume that the audience’s recognition of the voices will carry the film. This can be a “crutch” in the opinion of story man Ken Anderson. Or, it can add genuine depth to the character. Jiminy Cricket, Cruella de Vil, and Shere Khan’s final designs were based on caricatures of the actors who did their voices.

“It’s a dangerous situation to get into, basing a whole conception of charac-

ter around a voice talent,” says director John Musker. “We did write [the Genie in ALADDIN] for Robin Williams, not knowing whether he would do the voice or not” (interview by Nancy Beiman in CARTOONIST PROfiles, no. 97, March 1993). Had Robin Williams not been available, the part would have been rewritten, although the basic story of ALADDIN would not have been affected. Voice acting is 50 percent of the animated performance, but the visuals and the story construction should be supplemented by the soundtrack, not the other way around. A strong animated story and good characters will carry the picture so that its success does not depend on audience recognition of celebrity voice talents.

Animation and music go together like peanut butter and jelly. The popular cliché of the animator is that of the frustrated actor. I maintain that we are frustrated dancers—we work out story in motion, like ballerinas, though in most cases without the tutus. A good scratch track will help you time your action when you are assembling your story reels or animatics. This is discussed in Chapter 19.

Animated musicals have been with us since the beginning of sound film. What makes the good ones work? The secret is this: the songs don’t just “happen.” You will find that the songs in successful animated musical films fall on major story beats or turning points in the story and help to advance it. Songs can describe the characters’ dreams and motivations or comment on the action. Poorly-timed songs can stop a story dead in its tracks. Remember to never lose sight of your story. Never have someone burst into song just ‘because they can’ unless you are doing a parody of a movie musical.

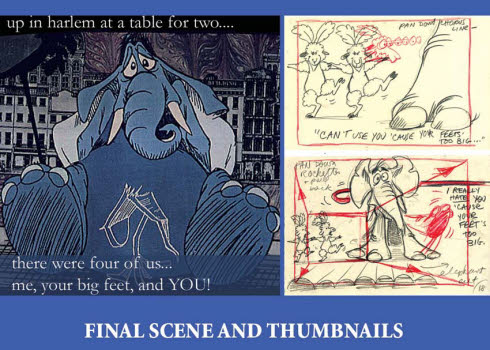

Use a few boards to illustrate one or two lines of a song in the sequence just as you do when creating beat boards from story outlines. Songs, like poems, have recognizable beats that can be translated into visuals. If you are working with instrumental music, synchronize the action to the musical beats.

[Fig. 15-4] My film YOUR FEET’S TOO BIG was edited to the witty song lyrics by “Fats” Waller and to the rhythm of the music.

So what does a story artist do when they are handed a couple of pages of a script? A feature film may have a script at an early stage, though it will be subject to change depending on what develops on the boards. Let us use a familiar story to illustrate one way of adapting a written script to a storyboard. Here is a short excerpt from a hypothetical script based on the Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Abbey Grange by A. Conan Doyle.

SEQ. 1.1 (HOLMES, WATSON)

DARKNESS.

FADE UP and PAN to a gaslight that illuminates the frame as a hansom cab pulls up in front of a dark building. It is 2 A.M. on a rainy London night in 1897.

SHERLOCK HOLMES:

Stop here, driver.

The cab comes to a stop and SHERLOCK HOLMES rushes rapidly out the open door.

EXT. 221B BAKER STREET—NIGHT

Lightning illuminates the house number as we hear a door slam.

INT: WATSON’S BEDROOM—A FEW MOMENTS LATER

The room is in near-total darkness. There is an indistinct figure in a bed. Rapid steps advance upon the stairs and a door bursts open. A figure with a candle stands in the doorway for a moment, contemplating the scene.

SHERLOCK HOLMES:

Watson!

Holmes’ face is illuminated by the candle. He is a thin-faced, wide-awake man dressed in the traditional deerstalker and cape.

SHERLOCK HOLMES:

Sir Eustace is dead, his head knocked in with his own poker!

Holmes advances toward Watson’s bed with the candle.

SHERLOCK HOLMES:

Come, Watson, come! Into your clothes and come.

Holmes pulls the blankets from the bed, revealing Watson in pajamas. Watson does not get up. Holmes rushes to the dresser to get Watson’s clothing and tosses it onto the bed.

An animated script will not contain extensive descriptions of the background since that is the story artist and art director’s job. Only a bare-bones description appears for now.

Adaptations of literary stories are notoriously hard to do. Some are far more visual than others. Some provide clues to the character’s personality. Sherlock Holmes is a familiar character with established mannerisms. Here are the points you should consider when translating any story to storyboard:

- What is the tone of this story? Is it dramatic, comical, satirical, or tragic?

- What do the characters feel? Are they happy, apprehensive, or indifferent?

- Whose viewpoint will we see the action from? Do we identify with a particular character? Are they large or small? This will determine the camera angles.

- How does the action progress, and why does it happen?

This example is only an exercise. In an actual production your story head or your directors would tell you how they wish the story to be interpreted. You would also be able to read the entire script to see how matters progress in earlier and later scenes.

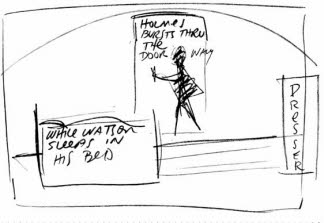

The first step is to break down the scene ‘by idea.’ Draw extremely rough thumbnails for each setting and determine which area of the frame will be the center of interest. Create a ‘concrete poetry’ sentence that describes the action in the setting, writing directly on each object in the panel as shown in Figure 15-5. Illustrate sentences, not words, and don’t include dialogue. There are two main settings in the sequence: (a) the exterior of Holmes’ and Watson’s house, and (b) Watson’s bedroom.

An animated sequence can be constructed like a sentence. Use the concrete-poetry method to clarify your thoughts and emphasize what is primary and what is of secondary importance in the sequence. Holmes is the active figure so the sentence and staging in the Abbey Grange excerpt focuses on him.

[Fig. 15-5] A sentence describing the setting, characters, and action is written inside the thumbnail panel. “Holmes bursts through the doorway while Watson sleeps in the bed.” Once the stage is set, the action can begin.

I decide that this story will be staged as a comedy. I will contrast Sherlock Holmes’ frantic action with Watson’s immobility. I decide that Watson doesn’t want to get out of bed because he has had too much to drink the night before. Does the script say this? No, but since this is my own production I have perfect freedom to add additional material to flesh the action out. The same material could just as easily be staged dramatically. The director or story head will guide you on a professional production.

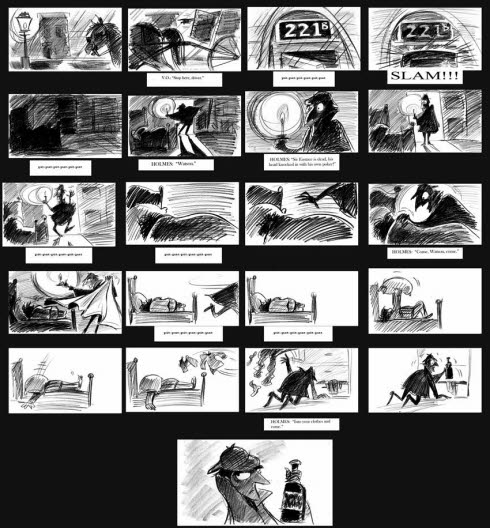

I next draw thumbnails in silhouette to examine possible staging and then rough out the action with the pictures and dialogue on separate panels as shown in Figure 15-6. I decide to keep the final action in silhouette for artistic reasons. Instead of following the script directions literally, I add some material with Watson go-

ing back to sleep and get Holmes over to the dresser before his last line so that he doesn’t see Watson’s reaction to his wake-up call. The last shot offers an explanation for Watson’s behavior.

You should always work for clarity in your drawings. The staging and acting should never be open to misinterpretation. Add another storyboard drawing to clarify the action or acting if the meaning of a scene is in doubt. It is preferable to have too many boards than too few to convey the story. The boards must direct the viewer’s eye where you want it to go and not have distracting elements in the frame.

Since the characters in this story appear in silhouette on many of the boards, I use a spotlight effect from the doorway to frame Holmes, who remains in silhouette throughout. He is the center of interest since he is the greatest contrast in the frame and appears in the optical center. Light from the candle directs your attention toward Watson’s bed, where I’d like you to look next. When the action becomes more frenetic I draw the characters on the white panels without rendering the backgrounds at all. We accept that the action continues in the same dimly lit room. I was able to build on this ludicrous start by having things go from bad to worse. Holmes eventually wakes Watson with a hotfoot, causing his friend to leap onto the chandelier, which falls, hitting Holmes on the head. The ending showed Watson solving the crime and getting “the girl” while Holmes is recovering (and still wearing the chandelier).

[Fig. 15-6] The rough boards show how the script has been modified. Holmes’ reaction to Watson’s disinterest adds a pause that was not indicated in the script. Written sound effects give a rough idea of the timing even though this won’t be finalized until the boards are cut into the story reel.

[Fig. 15-7] Silhouette values worked very well to convey the farcical action in this absurd interpretation of the classic Sherlock Holmes story.

Before the pitch, I’ll draw rough character designs for Holmes and Watson or paste up action model sheets to show at the same time as the storyboards. I will frequently pitch all the artwork to another artist beforehand to see if everything is reading well. When I am confident that the sequence is ready to show, I pitch the boards and character artwork to the (hopefully) appreciative audience. Chapter 18 lists things to do and not to do during a storyboard pitch. Wish me luck.

Exercise: Try thumbnailing the script from The Adventure of the Abbey Grange in a different manner and mood than I have done. After you have finished, design rough model sheets for Holmes and Watson based on your storyboard sketches. Can you make these familiar characters seem new and different?