Interview with Ken Anderson

Ken Anderson worked in story and development on many Disney features. His art direction credits include ONE HUNDRED AND ONE DALMATIANS, THE SWORD IN THE STONE, THE JUNGLE BOOK, and THE RESCUERS.

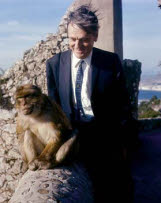

Ken Anderson and friend. Reproduced by permission of Cyndy Bohanovsky.

NANCY BEIMAN: Ken O’Connor’s been bringing in a lot of stuff that you did. You seem to have done practically everything! My main questions will be about story, since we don’t have a lot of information on how to recognize when a story has good potential for animation.

KEN ANDERSON: You don’t mind if I ramble a little bit?

NANCY BEIMAN: No.

KEN ANDERSON: In the last 15 or 20 years the emphasis has been [in the right place] on animation. There is a tendency to specialize. [But] there is no reason why a good animator can’t also be a good story man. I have to go back to the beginning to make my point a little more clear. We were all animators.

We were interested in animation as an art form and also as a way of expressing ourselves. And we were, or are, more or less, all frustrated actors. We feel acting, and we also feel art and design, and try to put that over [in the films]. Every one of the animators in the early days was also an idea man. Some of the animators were more interested in telling stories than others were. I believe that everyone who is involved in animation should also be involved in story. Which is what intrigues me with your question; it’s a bit unusual, because it seems to me that that [ability] has been lost sight of in the industry.

There is no way that I’ve ever heard of that is a ‘sure thing’ in constructing a story. But there are a few guidelines that I learned, not things that I knew instinctively. I had to learn them through experience.

If you are considering making an animated feature, you must remember that the animation medium is predominately a pantomime medium. The most important thing in it is body language and expressiveness, put over by the way the characters move. This should not be overwhelmed by an excess of dialogue. The moment that this happens, you have an audio, or radio, medium and you really don’t need the pantomimic gestures to put it over. The virtue of the medium as we know it today is that it is worldwide. Pantomime is understood everywhere, even though certain little gestures, in certain countries, mean the opposite. The basic movements of the human body—recoiling in fear, laughter, and so on—are all recognized universally, so pantomime has a very broad base of communication.

Walt said something that stuck in our minds. He said, “You don’t write a Disney feature. Building a Disney feature is a lot like building a building, with building blocks. Our building blocks would be ‘personalities’.” It would be better for our purposes if those personalities were abrasive, or if there was some sort of conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist, because this gives you more room for entertainment and communication. In the early days we discovered that a true story line or “clothesline” for an animated feature would work best if the story line was extremely simple. If you could go from A to Z in as simple a direction as possible, you could hang more entertainment on that simple story line. It is very easy to explain why ‘this’ problem created ‘that’ problem and then ‘that’ problem all built and led, in consecutive order, to a finish. The extraneous things that were least entertaining and least helpful to the development of the story line would be gotten rid of. The better ones, we’d keep.

NANCY BEIMAN: Did you write the treatment first?

KEN ANDERSON: Oh yes. Your treatment—it’s not a script, because we don’t get too involved with dialogue, we just get involved in the ‘clothesline’. We weren’t trying to pass ourselves off as writers. We were writing a theme. If we can hang sequences on the clothesline, it’s going to work. Simple stories are defined. This is the [type of story] that you should try to have. But it’s not easy to come by.

NANCY BEIMAN: Nearly all animated films—I can think of very few exceptions—have been made from children’s books. There is a lot of very good fantasy being written for adults. Has there ever been any attempt to develop something like that and would there be a potential for this type of story?

KEN ANDERSON: Yes, I think so. I’m sure there are many doors to be opened that can be opened. But we didn’t consider SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS to be a child’s fantasy. Adults then weren’t so afraid to be associated with things that children liked. During the past 20 years it seems that adults before the age of 50 don’t want to be associated in any way with something that is perceived as ‘childish’, and after 50, there’s no hope!

NANCY BEIMAN: Movies have become more diversified instead of appealing to a family audience.

I really would love to know how you go about taking a story sketch and breaking it down into camera angles. How do you know when one shot is going to work better than another?

KEN ANDERSON: I think that in order to plan the story sketch, you have to be primarily an animator, whether you are actually going to animate the scene or not. Unless it is a purely scenic shot where the animation is incidental, where there’s some lovely establishing mood that has to be established. Otherwise you can’t create something in story sketch if you are not thinking of animation. There is an ideal way, I think, of working. It involves thumbnailing entire pictures. I would go through breaking down sequences and scenes and how they would be animated. I’d do my own version of how the dialogue and staging would work best for particular actions. Thumbnails have to coordinate sound, picture, dialogue, and you have to be able to decide whether the script is useful. Nine times out of ten an animated feature cannot be written. It has to be visualized. The thumbnails could even be shot and timed. We would add scratch dialogue. And this became a “Bible.” We’d do the whole picture, not just sequence by sequence. Each animator would be given a copy of this book [of thumbnails] for the whole picture before he came onto it. The animator would say, “I have a better way of doing this,” and could substitute his own way of what the thumbnail action should be. Everyone should build the building if they can, and if theirs was better, it would become the version that was used.

NANCY BEIMAN: I sometimes have trouble distinguishing the thumbnails from story sketches. You use several different drawings for a scene where the storyboard might use only one.

KEN ANDERSON: It depends on who is doing the story sketch. In this case, it was Bill Peet. … He had a feeling for putting over scenes, too. Everything here is a re-evaluation. In most cases, there was no prior storyboard sketch for them. There was just writing. Bill’s story sketches were undoubtedly a help.

NANCY BEIMAN: Would you work with inspirational drawings?

KEN ANDERSON: That’s right. I also did some of them, and some of the storyboards, though more of those were done by Bill Peet. I took the storyboards and developed them a step further.

NANCY BEIMAN: So your cutting is determined by motion?

KEN ANDERSON: Yes, by putting over the idea of motion. I would make many, many sketches [for each scene in the sequence]. It wasn’t just blind searching, because the minute you know what your story situation is, what you are trying to put over, you begin to have preferences: should it be real close, long shots, should you be looking down or up? Every part of your experience is used to interpret that particular instant of movement.

There are all sorts of reasons for angles—it might be a low angle if the viewpoint is Jiminy Cricket’s. There are reasons for moving the camera. You maintain a mood with the camera angle and the station point.

NANCY BEIMAN: Were you influenced by live-action directors?

KEN ANDERSON: Absolutely. I used to go to the movies all the time and make sketches and drawings of how they put over certain things; [thumbnails of] staging in live-action pictures. Walt got hold of that, and one day we began to have classes on this very thing; cutting, staging, and storytelling with light. All the good pictures communicated with the audience. Today I find many pictures that have confused cutting—too fast, or with people going in different directions. They do that on purpose. They don’t want you to know what’s going on. They really don’t want you to catch up with them until they can surprise you with the ending. It’s a different way to put things over than my training.

NANCY BEIMAN: Have you ever tried to do this sort of cutting in animation?

KEN ANDERSON: Sure. I think there’s no holds barred for anything that you can do to intrigue and entertain an audience. Obviously the new film held my attention or I wouldn’t be talking about it. It was just hard to follow. We were afraid that if we did not let the audience know very clearly what story point we were trying to make, we could lose them for maybe a whole sequence.

NANCY BEIMAN: Is there a tendency to be a little over-obvious in the staging of animated cartoons?

KEN ANDERSON: I think so. Almost so that it becomes boring. But I think that no one is really equipped to do the cutting that is being done today unless they understand the staging that we were talking about earlier, which is very basic. If you understand how to communicate then you can deviate from it in the same way that knowing the scales on the piano enables you to play a complex piece of music. You can bang on a piano and make a lot of sounds that may not have any relevance to the people who are listening to you.

NANCY BEIMAN: You were sole character designer on the later Disney pictures. I notice in the thirties and forties, character designs seemed to be more of a group effort. Do you get better results when you have a group of people to bounce ideas off of?

KEN ANDERSON: Oh yeah. From the very beginning, every one of us overlapped into everything on the picture. It was a real delight. Everyone was involved in learning all the other facets of the production. Then you gravitated toward whatever your strengths were. Frank Thomas never gave up! He was a story man, an animator; he was interested in background painting and everything else, which is the way it was supposed to be. Ollie [Johnston] was the same. And I never got over animating, either! We interacted in every way. And some of us, because of the immensity of the project, found we had to level on something, because if you kept bouncing around you’d never get anything done. I found that I liked to level on the overall picture, the characters and the story situations. I gravitated on my own accord to the story department. I liked mood and locale also. But I kept animating scenes on my own just so I wouldn’t forget how!

The day is coming when any person can make a film all by himself. And that is the optimum. But then if you have many artists, as in the great ateliers, each making their own painting or sculpture, the atmosphere is very invigorating. Many animators could work in one studio on their own projects. Think of the variety of films that will occur!

When writing for animation, if any one of us wrote the lines, and we knew which actor was going to play the part, we’d say, “This is what we want but we want it to come out of you. If you see a better way to say it, you should build on it.” That is part of the building block process I referred to earlier. There’s another thing to take from Walt: making a feature, to him, was like planting a seed. You want to have a plant with one beautiful bloom. You plant the seed and fertilize it, and prune it to make sure that the strength is not going to the wrong buds. You allow one beautiful bud to bloom and you’ve got your feature picture. But you don’t stand around and admire it; you plant another seed.

NANCY BEIMAN: What sort of problems would be posed by work in short films as opposed to features?

KEN ANDERSON: The short film doesn’t need to hold a person’s attention for a long time so you can get away with a lot more; be a little offhand, less concerned with what is going to happen in subsequent sequences. It’s a comparatively short piece of film and so its problems are extremely simplified. You can hang a short film on one character. You don’t necessarily need two or three, although it’s better to have at least one foil.

NANCY BEIMAN: Well, the advantage is that you don’t have to make your point in a feature. The disadvantage of a short is that you have to make your point in six minutes or less.

KEN ANDERSON. That’s true. It works both ways. You can concern yourself, if it is a musical short, primarily with entertainment. Some of the earliest Disney shorts were nothing more than movement to music.

NANCY BEIMAN: If you have a good story, how do you make a presentation out of it? Do you work your story sketch up immediately from thumbnails?

KEN ANDERSON: First of all, I will probably start visualizing the characters, making drawings so that I will have something to make little thumbnails from. It’s almost the same as writing a book. But you can’t write a story without characters and you can’t get characters without the story! You have to have something to illustrate, and so I start fooling around with the characters. They keep changing—they keep getting better, as the story develops.

NANCY BEIMAN: Would you do a script treatment of the story after you had actually started drawing characters, or would you do them at the same time?

KEN ANDERSON: My script treatment would probably be done more or less coincidentally with the characters. Each one leads the other. As you find a simplified version that you are likely to work with, you are likely to see a flowering of certain portions of it. This gives you an impetus to move on to something else. One thing takes precedence for a while, then the other catches up, and so you finally arrive [at a finished story with characters set]. The written form is just a nice simplified version of a treatment. You should make it clear and very simple so that your story evolves through the relationship of the characters. Each entertainment situation will help the story progress.

NANCY BEIMAN: Do you occasionally find the story going in a different direction when you start doing your thumbnails?

KEN ANDERSON: It certainly has happened.

NANCY BEIMAN: Your script is not the final word?

KEN ANDERSON: Oh, no. The chances are that the script will be superseded by storyboard, to the extent that when you get through, your original writer may not recognize the story that has turned into something quite different from what you started with. This is not so much an intention as a development. It grows so far away from the original that it demands new writing.

NANCY BEIMAN: Do you like to write original material as opposed to adapting something that has already been written?

KEN ANDERSON: I think that nowadays, you don’t have to rely on a pre-sold story to a pre-sold audience. If you have a great story, if you can get it produced and distributed, you would easily succeed. Animated films can be made using a wholly different way to reach the audiences than they used in the past. I sure hope that this happens. I don’t think we are at the ‘end’.

NANCY BEIMAN: The color in modern films tends to be more garish than formerly. Older films used more muted tones. Violent colors are appropriate for a garish character like Medusa, but every character seems to be that way nowadays. Sometimes the characters do not seem to fit with the backgrounds.

KEN ANDERSON: In ONE HUNDRED AND ONE DALMATIANS, everyone suggested using muted grays on the backgrounds since this film took place in England. England is not a country that is associated with garish colors, considering the weather that they have. I found that [the limited palette] was a strength; it brought us full circle to SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, which had been designed in earth colors. BAMBI looked as good as it did because of the art of Tyrus Wong. Ty had a beautiful way of emphasizing a highlight in a forest and let it melt off into color tones so that you felt you were seeing a whole scene where only a part of it was actually painted.

Somebody has to have control over the color and style of each picture. Eyvind Earle’s personal style of painting had a tremendous influence on SLEEPING BEAUTY; the characters were influenced by the backgrounds which were done first, with the strange angular design, and the characters came along later. And there was Mary Blair, who was just a natural colorist. Earle came to his color combinations mathematically.

NANCY BEIMAN: In character design, is it good to have a ‘studio style’ or to keep experimenting?

KEN ANDERSON: Inherently, for your own growth, and for the growth of the medium, it’s wise to keep experimenting. We never tried to come up with a style. It’s simply that certain shapes and forms are easier to move. Certain shapes make it easier to get expressions.

NANCY BEIMAN: What sort of reference do you use for character design? What if you were designing a mythological creature that you could not see in a zoo?

KEN ANDERSON: I research everything I can. For an actual creature, I get every photograph or book that I can find. I immerse myself in as much knowledge of the creature as I can, make it a part of me. Then I decide that some things have to adapt but I can make the adaptations based on what I know. The material leaves me better prepared to come up with something new. For mythological creatures: in the back of my mind I would think of an actor (say, Wallace Beery) when designing a particular dragon. So I was drawing dragons with that feeling of Wallace Beery. Shere Khan the tiger in the original THE JUNGLE BOOK was a terrifying menace.

He doesn’t appear until the last two sequences of the picture. We had to see why everyone else was afraid of him. I was stymied but had to come back with something. I thought of Basil Rathbone, but he was no longer around even at this time, so I used him as an inspiration. Shere Khan didn’t even have to show up, he just was. I didn’t try to draw him to look like a caricature of Basil Rathbone, but to have that quality of high-and-mightiness so that his appearance told you that he was this kind of creature. Walt looked at the drawings and said, “Oh, I know who that is, that’s George Sanders.” Milt Kahl, who loved it, developed the design much further but they were based on the sketches I did. So this is an example of a design that was based on a well-known person.

The vultures in [THE JUNGLE BOOK] were based on some of the animators! They wound up as the Beatles, but at the start, they were caricatures of the animation crew. Many times you are in danger of falling into the trap of caricaturing an actor or actress. What you really should do is create a new character that has the actors’ attributes that help put over your story point. You never know where anything that influenced you is going to show up. And it will be subconscious, unless you are trying to do a conscious imitation of the style.

NANCY BEIMAN: How much do your character designs change by the time they reach the screen?

KEN ANDERSON: Generally, I’d say that they were pretty much right on. Most of the animators would better, or strengthen, the designs. But nobody ever gave anyone a command to stay right on that same model. We all believed Walt’s tenet, which was “Everyone who has an input [into the film] must feel free to keep in-putting anything they can.” If some animator made arbitrary changes, they would have to be prepared to defend it, explain why it was better. If they made changes, it was because they were generally stronger.

The thing I would like to impress you all with is this: we didn’t have anyone to talk to. We had to learn all of this the hard way. Nobody knew.