CHAPTER 12

Security Administration and Planning

In this chapter, you will learn about

• Security policy contents and characteristics

• Raising the awareness of security policies

• Business continuity plans

• Business impact analysis

• Disaster recovery plans

• Difference between a BCP and DRP

• Alternative locations such as hot sites, cold sites, and warm sites

• Security organizations such as NIST and US-CERT

Understanding Security Policies

A security policy is a written document that provides an organization with a high-level view of its security goals. Chapter 9 presented and contrasted the differences among policies, standards, guidelines, and procedures. To quickly review, policies are high-level, authoritative documents. Standards document criteria such as a proven norm or method and may specify requirements for a process or a technology. An organization can choose to adopt some standards, while other standards apply to an organization based on partnerships or relationships with other entities. Guidelines provide recommendations for members of an organization, but they are not mandatory. Procedures provide the action steps to accomplish tasks.

A security policy is an administrative control that focuses on the management of risk and IT security. Senior management creates or at least endorses the organization’s security policy. The policy reflects the culture of the organization and provides the overall direction for security. Others within the organization use the security policy as an authoritative document to implement controls to enforce and follow the requirements of the security policy.

A security policy typically goes through several stages:

• Initial stage Personnel draft the security policy based on the needs of the organization. This might be a formal, nearly complete draft of the policy or an initial proposal to senior management identifying the needs and objectives of the policy.

• Approval stage Senior management approves the policy. It might take several iterations between the initial stage and the approval stage to create a document that senior management approves. Once approved, it provides direction for personnel to enforce the policy.

• Publication stage The policy is provided to relevant personnel so that they can follow and implement it.

• Implementation stage A security policy is an important first step to provide security within an organization, but it isn’t the final step by any means. After senior management has approved a security policy, personnel must take steps to implement and enforce it.

• Maintenance stage Periodic reviews (such as once a year) ensure that the policy remains up to date, meets the needs of the organization, and addresses current threats.

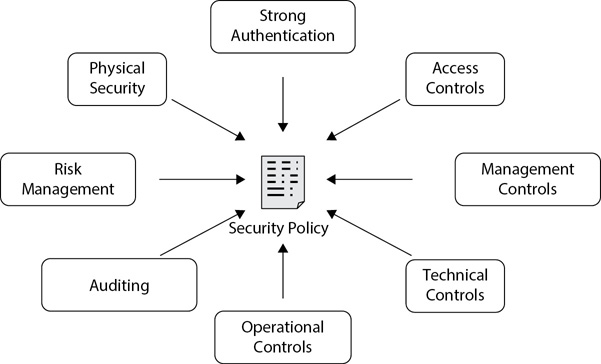

While it’s possible to have a single security policy covering all the elements of security for an organization, this can easily become very large and difficult to maintain. Instead, organizations often create several security policies, with a single security policy driving the others. As an example, Figure 12-1 shows the relationship between an organization’s security policy and other supporting policies. For instance, the security policy can mandate the creation of an acceptable use policy (AUP) and require users to review and acknowledge the AUP periodically. Personnel then create an AUP to support this requirement. Similarly, the security policy may state that the organization needs to prepare for potential disasters and ensure that critical functions continue to operate during disasters. Personnel then create a business continuity plan, identify critical functions with a business impact analysis, and create disaster recovery plans to respond to different types of disasters.

Figure 12-1 An organization security policy and supporting policies

Some organizations use a similar approach but include the supporting policies as appendixes to the security policy. The primary document is the organization’s security policy and it refers to the appendixes. Each appendix addresses separate security concerns, such as an acceptable use policy, an auditing policy, and so on.

Security Policy Characteristics

There isn’t a single standard for creating a security policy. Depending on the size and needs of the organization, a security policy can be just a few pages long or 50 pages or more. However, you’ll see some common characteristics in many effective security policies, including the following:

• Organization mission statement A basic mission statement helps members of the organization understand the overall vision of the organization and how security can be used to enhance the mission and vision. The goal is for security methods and procedures to support the mission of the organization and its overall business model.

• Statement of accountability A security policy defines the roles and responsibilities of users, management, and IT staff. This section provides a basis for ensuring compliance with the policies and procedures.

• Data classifications An organization often defines the classifications of data (such as Confidential, Sensitive, Private, and Public) in the security policy. This section explains how to determine data classifications and provides some guidance on protecting data based on the classification.

• Backup plans Security policies often dictate the requirements for overall backups. This includes backup requirements, offsite storage of backup copies, and how long to retain backups.

• Classification of resources A security policy can identify specific resources that need higher levels of protection. As an example, consider an organization that hosts an e-commerce website with access to a customer database. The security policy can mandate the protection of the e-commerce website and require the database to be stored on a different server. Administrators choose the details of how to implement these requirements. They might choose to host the web server within a demilitarized zone (DMZ) protected with an intrusion detection system, and store the database on a separate server in the internal network.

• Network access This section defines the types of access authorized on the network. For example, the organization may restrict the use of any wireless devices on a network. If the organization allows wireless access, the policy may specify minimum encryption standards. Similarly, the policy might mandate the creation of a separate network with Internet access for wireless devices, but prohibit these devices from accessing internal network resources.

• Risk management In this section, the organization defines an overall view of risk management. This could include direction on risk assessments and vulnerability assessments, such as how often to complete these assessments. An organization may also provide direction on types of analysis that assessors should use. For example, the policy might direct the use of quantitative analysis or identify specific values to use in a qualitative analysis.

• Auditing An auditing policy defines what should be audited at a minimum and how often. For example, it can mandate extra auditing requirements for privileged accounts and require that nonadministrator personnel audit actions by these accounts at least every six months.

• Business continuity Most organizations include an overall statement regarding business continuity and disaster preparation. Separate documents provide the details, but the security policy provides the overall goal.

• Incident response An incident response section defines a security incident for an organization and provides information on what should be done in response to an incident. It could include overall direction on goals to prevent, detect, and respond to security incidents and require the creation of an incident response team.

• Physical security This section provides an overview of physical security requirements. It may mandate the creation of a zone document for the building. The zone document identifies the specific protections required when processing different types of classified data and specific zones within the building. For example, a server room may process confidential data and require protections such as a single video-monitored entrance/exit that can be accessed only with a smart card and PIN.

• Acceptable use Most organizations draft acceptable use policies to let users know what is acceptable use of computer equipment and networks. The security policy may mandate the creation of an acceptable use policy and identify how users acknowledge it, such as by signing an acknowledgment that they have read the policy. The policy will often specify when or how often users should acknowledge it, such as when they are initially hired, and annually thereafter.

• Enforcement section Many policies identify an overall vision of how a security policy is to be enforced. For example, the policy may state an overall goal of using electronic monitoring and technical controls to enforce policy elements whenever possible. Similarly, it might mandate periodic training to ensure personnel are aware of the security policies.

• Passwords and other authentication requirements A policy can generically state the overall authentication requirements. For example, it may state that a technical password policy must ensure that users create strong, complex passwords and that they change them regularly, or that access to certain systems requires the use of two-factor authentication. Many organizations require administrators to have separate administrator accounts and use longer and more complex passwords for the administrator accounts than they use for their regular user accounts. When services require separate service accounts, these can have different password requirements.

• Account lockouts The policy can require that accounts automatically lock after users enter the incorrect password too many times. Further, it can require technicians or administrators to unlock the accounts manually.

• Hardware usage The security policy can restrict or prohibit the use of some hardware. For example, USB flash drives have specific risks such as the ability to transfer malware from system to system, or allow an employee to steal massive quantities of data. Many organizations restrict the use of USB flash drives to reduce these risks. A security policy can mandate the use of technical methods to prevent the usage of USB drives altogether, or to prevent systems from reading data from a USB drive or writing data to a USB drive. The policy can also require technical controls to detect and report any user attempts to use a USB drive.

• Ethics statement An ethics statement identifies the minimal acceptable behavior by members of the organization. The security policy can include an ethics statement identifying the organization’s expectations related to ethics and directing an employee of what to do when faced with an ethical dilemma. In general, most organizations expect employees to resolve ethical dilemmas within the organization by going to their supervisor, or their supervisor’s supervisor, whenever possible.

Enforcing Security Policies

Of course, security policies are useful only when personnel know about them, implement them, follow them, and enforce them. This is one of the reasons that senior management must endorse and support security policies. If not, the policies become meaningless documents.

Figure 12-2 shows some of the methods used to enforce security policies. You’ll find these controls covered throughout this book. For example, Chapter 2 covers authentication and access controls; Chapter 7 covers risk management topics; and Chapter 9 covers several different types of administrative, technical, and physical security controls.

Figure 12-2 Enforcing a security policy

These elements work together to provide a defense in depth security solution by increasing the overall security posture of the organization. An important point worth stressing is that, ideally, the security policy comes first, and then personnel implement security controls in support of the security policy. The goal is for these controls to enforce the security policy and support the overall mission of the organization.

Value of a Security Policy

The obvious value of a well-crafted security policy is that it increases security and security awareness. If the security policy can prevent or at least reduce security incidents, it can protect an organization against direct financial losses, as well as indirect losses through damage to its reputation. However, there are also some less obvious benefits.

Direct Losses vs. Indirect Losses

Direct losses refer to the immediate losses resulting from an incident, such as the loss of revenue. Indirect losses refer to other factors such as the loss of customer goodwill. Accountants refer to direct costs as any cost that can be traced to a specific cost object.

As an example, the Equifax data breach of 2017 resulted in losses of $164 million in 2017. They reportedly expect to lose an additional $275 million in 2018, with total expected losses of $439 million through the end of 2018. Many of these costs were related to technology and security upgrades, free identity theft services for con-sumers affected by the attack, and legal fees.

The company purchased an identity protection company for $63 million after learning of the data breach, but before disclosing it to the public. They then used this to provide free identity protection services to consumers affected by the data breach. This is an example of a direct cost.

Shares of Equifax were trading close to $143 before they announced the data breach. After reporting the data breach, shares fell to $116. This reflects an indi-rect loss.

Even if a security incident occurs, the security policy may limit the organization’s liability. As an example, consider a similar attack against two different fictitious organizations, ACME and EMCA. The attack exploits a zero day vulnerability and results in the loss of customer data. ACME doesn’t have a security policy, and personnel have not documented their security practices. EMCA does have a security policy, and has a significant amount of documentation showing that it regularly follows security practices. ACME will be more vulnerable to litigation claiming that the company has not taken steps to protect customer data. In contrast, EMCA may be able to demonstrate that it did everything it could to prevent losses, so its liability would typically be limited.

Similarly, when employees sign security policies (such as an acceptable use policy) to acknowledge that they have read the policies and are aware of their contents, they can be held accountable to follow the security policies. Most employees won’t knowingly violate security policies. However, some employees may purposely try to circumvent them, which can cause additional harm to an organization. For example, if an employee surfs pornographic sites using a company computer (counter to the AUP), fellow employees may see the objectionable material and raise sexual harassment issues. In the absence of a policy, the company may be liable for the sexual harassment. With a policy in place, the company can hold the offending employee accountable.

Security Policies Becoming More Common

Organizations are increasingly required to have security policies, typically because a higher authority mandates them. For example, the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) requires organizations processing credit card data to meet multiple security control objectives and requirements, as detailed in Chapter 10. One of the requirements is to maintain a policy that addresses information security.

Some organizations aren’t required by law or regulation to have a security policy and they consider it too expensive or too time-consuming to draft, implement, and enforce. This view often changes after one or two costly security incidents. The lack of a security policy can often cost much more in the long run.

Without a policy providing guidance, employees must use their own judgment to decide what they think is important to the organization. At the very least, these decisions will be inconsistent and can easily result in the loss of confidentiality, availability, and integrity of IT systems and data. Worse, the lack of direction often results in wasted efforts, rework, and higher costs.

Data is often one of the most valuable assets within an organization, but not all data has the same value. Without guidance, employees could easily overprotect public data and under-protect highly confidential data. For example, if IT personnel don’t recognize the value of research and development data, they may not use strong access controls to protect it or may not back it up often enough. An attacker may be able to hack into the system and steal the data, or a common hardware failure may result in the loss of a significant amount of research data. Both scenarios can result in the organization’s losing a significant amount of money.

It’s also worth noting that if an organization doesn’t have a security policy, it may be susceptible to other legal problems, including liability issues. For example, if an organization doesn’t have an acceptable use policy and an employee uses a computer to hack into other systems or networks, the company can be held liable. However, an organization reduces its legal liability by having documentation (such as a signed AUP) proving it has informed employees of unacceptable practices.

Complying with Codes of Ethics

Chapter 1 covered the Code of Ethics required by (ISC)2. As you’ll recall, you must subscribe to this Code of Ethics to earn and keep the SSCP certification. The Code of Ethics includes responsibilities such as protecting society, acting honorably, providing diligent and competent service, and advancing and protecting the profession.

However, the (ISC)2 doesn’t have a corner on ethics. Many organizations have their own ethics statement that provides guidance to personnel related to their conduct within the organization. When employees sense a conflict based on the organization’s stated ethics, they have a responsibility to raise this internally within the organization rather than reporting it externally.

It’s unlikely that any security policy will cover every possible issue that can present itself within IT security. This is where ethics come in. They provide a framework of norms and principles of correct conduct beyond the security policies. With this in mind, employees of an organization have a responsibility to ensure that secure practices are still followed even if there isn’t a specific policy that covers a particular challenge.

One point worth stressing is that employees should not retaliate against attackers, even if an organization doesn’t have a policy addressing counterattacks. The exception is when it is part of the cybersecurity professional’s job. For example, if an attacker launches a SYN flood attack on one of your servers, you may be able to analyze the logs and determine the source of the attack based on the IP address. You may be tempted to launch an attack against the attacker, but this is not ethical. It can also result in unexpected results.

First, the attacker may be spoofing an IP address. Even though you think you know where the attack originated, you may be attacking an innocent company server that the attacker hijacked and used to launch the attack. Second, when you launch an attack, you are escalating the situation. If you block the attack, the attack stops and the incident is over. If you attack back, the attacker may take it personally and launch multiple malicious attacks against your organization for days, months, or even years afterward.

Policy Awareness

After an organization creates and approves a security policy, it’s important to ensure that the appropriate personnel know its contents. Having a policy hidden away in a desk is almost the same as having no policy at all.

Different members of an organization require different levels of understanding of a security policy. In other words, regular employees need to understand some topics within the policy, but not necessarily all the topics that security and IT personnel need to understand. As an example, all employees must be aware of an acceptable use policy.

In contrast, imagine the policy states that two-factor authentication is required when accessing the network via a virtual private network (VPN). IT and security personnel would design and implement an appropriate two-factor authentication system (such as with smart cards and usernames and passwords). Personnel using the VPN would need smart cards to authenticate via the VPN. However, users who never use VPNs don’t need to know about the policy requirement. Similarly, users who do use VPNs don’t need to understand the technical details of multifactor authentication, as long they know they must use a smart card with their username and password.

The following sections cover some common methods that help ensure personnel know the relevant details within the security policy.

Easy-to-Read Language

The policy should be written in language that is simple to understand. If the policy is too complex for the target audience, they won’t understand it and very likely will not follow it.

As an example, if the policy states that passwords must have at least 30 bits of entropy, most people won’t understand what that means. However, personnel will understand the policy if it states that passwords must have at least eight characters, include at least one character from all four character types (uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters), and must not include the user’s name.

Warning Banners

One of the ways that you can let users know of relevant security policy contents is with warning banners. Administrators can create warning banners that appear each time a user logs on. Warning banners can define who is considered an authorized user and warn unauthorized users against accessing the system.

Some organizations go further and provide information to users on their expectation of privacy within the warning banner. For example, many organizations regularly monitor user activity. A warning banner can remind users that tools are monitoring their activity to detect improper or illicit use of computer systems and networks. The warning banner could also list penalties for noncompliance with the organization’s acceptable use policy. These warning banners remind users of their responsibilities and help serve as a deterrent.

Training Sessions

Some elements of a security policy may require training to implement. Organizations typically target training to different groups based on the needs of individuals within the group. For example, an incident response team may require forensic analysis training to ensure they are able to respond to incidents, identify what happened, and limit the potential damage.

Regular users might only need annual training on the acceptable use policy and periodic training on emerging threats. For example, attackers continue to create different types of attacks and change techniques in older attacks. Periodically educating employees about current attacks such as phishing attacks can help employees recognize malicious e-mails and avoid malware infections.

Many organizations provide this type of training by using online methods, such as via an internal website. However, even a simple e-mail can inform users of a current threat. For example, one phishing attack sent a ZIP file to users as an e-mail attachment, with the e-mail message indicating that FedEx was unable to deliver a product to them and instructing them to open the file for more information. However, the ZIP file included malware designed to infect their system when users unzipped the file. Sending an e-mail to users within the organization to inform them of the phishing attack not only helps them to avoid opening the file, but also helps them to recognize how phishing attacks morph over time.

Security Flyers and Posters

Some organizations use security flyers and posters to raise security awareness and remind people of the security policies. The goal is often to get the users to recognize that security is their responsibility too, not just something the company does.

Updating Security Policies

Security policies are dynamic documents. An organization that creates a security policy but never updates it can’t expect the policy to remain effective. Organizations change as time moves forward. Similarly, threats and vulnerabilities change. By periodically reviewing and updating a security policy, the organization keeps up with these changes.

It’s common to schedule periodic reviews of a security policy as a maintenance stage. For example, many organizations schedule annual reviews. During this review, the organization can examine changes to determine whether the security policy warrants an update. Changes in the industry, business practices, laws, threats, and many other aspects may require changes in the security policy.

Additionally, an organization will often reexamine a security policy after a security incident. For example, if a security breach results in the loss of valuable data to an organization, personnel should examine the security policy and supporting practices. They may find that the security policy is inadequate and needs to be updated. Or, they may find that the security policy itself is adequate but personnel didn’t follow the policy. In that case, personnel might need additional training, or the policy might need to be more accessible to personnel who are responsible for implementing the policy.

Understanding BCP and DRP Activities

Business continuity planning includes all the processes and procedures to prevent the loss of mission-critical services for an unacceptable length of time. A business continuity plan (BCP) includes multiple elements, such as a business impact analysis (BIA) and a disaster recovery plan (DRP). A BIA identifies critical business functions and processes, and a DRP helps an organization restore critical systems to full functionality as quickly and efficiently as possible after a disaster.

Several events can result in service disruptions, including any of the following:

• Attacks

• Disasters

• Accidents

• Human error

• Equipment failure

• Software or application failure

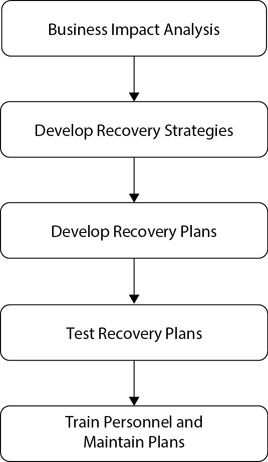

It’s worth stressing that business continuity planning isn’t a small endeavor and it requires the support of senior management. This ensures that business continuity efforts are adequately funded and that all elements of the organization support the planning efforts. When organizations take business continuity planning seriously, it entails several distinct action steps. Figure 12-3 shows the overall steps to develop a BCP.

Figure 12-3 Overall steps for a BCP

The business impact analysis (discussed in more depth in the next section) identifies critical functions within the organization and provides an important starting point. The organization uses the results of the BIA to develop recovery strategies, such as the use of alternative sites and different backup strategies. Once personnel identify recovery strategies, they develop and test plans to support the strategies. These plans include detailed steps used in response to disasters or emergencies. Last, personnel responsible for implementing the plans get appropriate training and begin implementing the plans. Personnel periodically review the plans and update them as necessary.

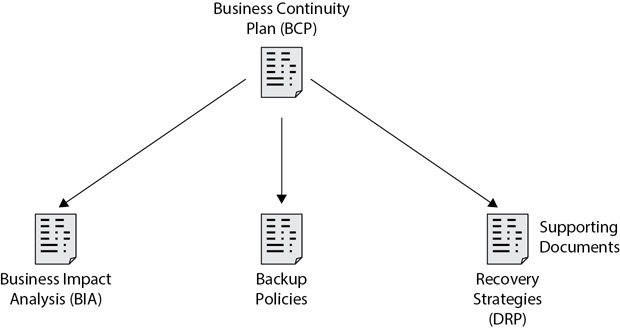

Figure 12-4 illustrates the relationship between a BCP and supporting policies. For example, a BCP starts with a BIA to identify critical functions. The BCP also includes backup policies outlining backup requirements and one or more DRPs that outline recovery strategies.

Figure 12-4 BCP and supporting elements

Some organizations are in high-risk zones for specific types of events, so they often create supporting documents specifically for these events. For example, an organization that is in a high-risk zone for hurricanes would have a document specifically targeted at ensuring that critical operations continue during and after a hurricane.

Before the hurricane season begins, the organization dusts off last year’s hurricane preparation plan and reviews it. It may decide that it wants to ensure that it is able to continue to operate critical functions for at least ten days after a hurricane hits. This drives other requirements, such as ensuring the location has at least ten days’ worth of diesel fuel for generators and at least ten days’ worth of food and water for personnel remaining onsite.

This plan would also identify steps to take as a hurricane is approaching, such as what to do when the hurricane is within 72, 48, 24, and 12 hours of striking. For example, when the hurricane is within 72 hours, personnel check to ensure they have enough supplies on hand and begin bringing everything inside to prevent potential damage. When the hurricane is within 48 hours of the facility, the organization tests the generators and ensures that everything can continue to operate if the storm hits. When the hurricane is within 24 hours, emergency personnel report to work and all other personnel go home.

Business Impact Analysis

A BIA is an important part of a BCP. It identifies the impact to the organization if any business functions are lost due to any type of incident. This information helps an organization identify what business functions are critical to continued operation. It also helps identify which resources are required to support these critical business functions.

For example, will the business stop functioning if a weather event causes a 24-hour or 48-hour power outage in a building? The answer depends on what functions are performed in the building and whether any of these functions are critical. If this building houses primary servers used in an online e-commerce website, the loss of power could cause the entire business to cease functioning. In this case, the purchase of generators for long-term alternative power may be justified. However, if the building houses products and shipping facilities, a 24-hour or 48-hour power outage may result in only a minor impact on operations.

The BIA evaluates both direct costs and indirect costs. As mentioned previously, direct costs are associated with the immediate loss, such as an immediate loss to sales, while indirect costs are expenses related to recovering from the loss. For example, if an e-commerce website normally generates $5,000 in revenue an hour, then the direct costs are $5,000 for every hour the server is down. However, the organization may have to spend money on public relations after an outage to assure customers that their personal information is secure, and this extra money represents indirect costs. Additionally, some customers may leave forever, causing additional indirect costs.

Maximum Acceptable Outage

One of the most important findings of the BIA is the maximum acceptable outage (MAO) for different systems or services. This is sometimes called the maximum tolerable downtime (MTD) or the maximum tolerable outage (MTO). If an outage lasts longer than the MAO, it affects critical business functions supported by these systems or services.

As an example, consider an online website generating $5,000 an hour during peak hours. After 60 minutes of downtime, it loses $5,000 in direct revenue. Management may determine that it has an MAO of 60 minutes. This includes all the elements required to support the online website, including web servers, backend databases, Internet access, and the network infrastructure.

The same company might ship products from a separate shipping warehouse. Management may decide that warehouse outages up to 48 hours will not affect critical business functions. As long as they communicate the delays with customers, the customers will accept some shipping delays. This results in an MAO of 48 hours for the shipping functions.

Recovery Time Objective

The MAO helps an organization determine the recovery time objective (RTO), which is the maximum amount of time that personnel can take to restore a system or service after an outage. If personnel take longer than the RTO to restore the system, the outage will affect critical business functions. If the MAO is 60 minutes, the RTO is also 60 minutes.

Administrative and security personnel also use the RTO to identify fault tolerance and redundancy methods. This includes Redundant Array of Independent Disks (RAID) subsystems and redundant servers configured in a failover cluster or load-balancing cluster. Implementing fault-tolerant and redundancy methods helps prevent the outages from occurring at all. For example, if a hard drive fails in a RAID, the system continues to operate. Similarly, if a server fails in a failover cluster, another server picks up the load and the service continues to operate.

These options can be expensive. However, if a web server generates $5,000 in revenue an hour and the MAO is 60 minutes, management may decide that the cost is justified.

Recovery Point Objective

A recovery term often associated with databases is the recovery point objective (RPO). It identifies the maximum amount of data that an organization is willing to lose. This is sometimes difficult to identify. If you ask managers how much data they are willing to lose, you’ll often hear “none” as the answer. However, after you identify the cost of restoring data up to the moment of failure, you will often get a more realistic answer.

If a database is relatively static, with just a few manual updates during the week, then management may determine that the RPO is a single week. In other words, backing up the database once a week is enough to meet this requirement. If a disaster deletes or corrupts the database, administrators can restore the database and personnel can manually enter the updates since the last backup.

In contrast, consider a database recording online transactions for a web server generating $5,000 in sales an hour. Weekly backups aren’t enough. If personnel back up the database on Sunday and a catastrophic database failure occurs on Wednesday, it results in the loss of all the customer transactions since Sunday. In this scenario, the RPO may be up to the moment of failure.

Although it’s certainly possible to create a backup strategy for databases to recover a failed database up to the moment of failure, such a strategy can be expensive. That’s why it’s important to complete the BIA to help determine the actual needs of the organization related to the RPO. If the BIA determines the organization has a need to restore the database up to the moment of failure, it justifies the extra expense to support this RPO.

BIA Output

One of the major deliverables of the BIA is a document that identifies the actual monetary losses that can result from the outage of a critical business function. This is invaluable when you are evaluating controls that can mitigate these losses. You may remember from Chapter 9 that the controls are valuable only if they cost less than the losses they’re trying to protect. For example, you wouldn’t spend $1,000 to protect a $10 keyboard. Similarly, you don’t want to spend business continuity funds protecting noncritical business functions. Although an e-commerce web server may be critical to an organization, an intranet web server used to track long-term projects may not be as critical.

The BIA identifies how much money can be lost if the e-commerce web server fails. This provides management with an idea of the justified costs to keep the system operational even during a major incident. When evaluating multiple business functions, the BIA also attempts to prioritize them.

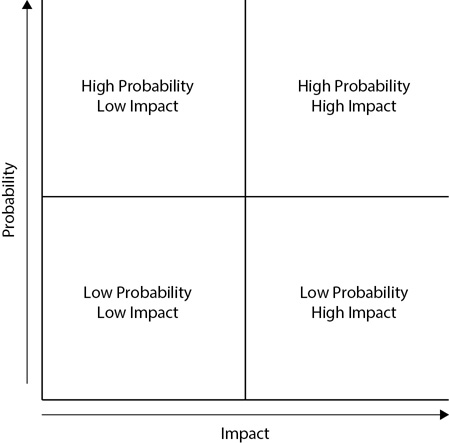

Figure 12-5 shows one way that a BIA can prioritize different functions by analyzing the probability of an incident occurring and the impact to the organization if the incident occurs. Incidents with a high probability and a high impact have the highest priority, while incidents with the lowest probability and lowest impact have the lowest priority. By graphing different types of disasters and identifying the systems that they can affect, an organization can identify the incidents that deserve the greatest attention.

Figure 12-5 Probability and impact analysis

Historical data helps an organization predict the probability of specific disasters. For example, an organization in San Francisco may consider the threat of an earthquake to be significant, while the threat of a hurricane may be nonexistent. Similarly, an organization in Miami may consider the threat of a hurricane to be significant, while the threat of an earthquake may be nonexistent. These are extreme examples, of course, and many other examples aren’t so obvious. However, by analyzing and charting the results, the organization can prioritize different risks.

It’s important to remember that historical data won’t necessarily cover all potential negative incidents. Still, it is possible to predict some of these negative events. As an example, an organization might never have suffered any losses from a cyber-attack in the past. However, with the level of ongoing cyber-attacks, it’s very likely the organization will be attacked at some point in the future. Personnel can predict the potential impact of a data breach based on the value of the organization’s data.

Disaster Recovery Plan

A DRP provides an organization with a plan to restore critical operations after a disaster. The overall goal is to provide employees who are recovering the systems with clear-cut steps to restore the systems.

Disasters are major events, and people don’t always think clearly when they occur. If employees have steps to follow within a checklist, they can ensure that they restore systems in a logical and orderly manner. On the other hand, if employees don’t have steps to follow, they may spend a lot of time trying to determine what to do, and then more time redoing their steps when things don’t work as expected.

Emergency Response Plans and Procedures

Disaster recovery plans include emergency response plans and procedures, and an organization will often have several different DRPs in place, ready to respond to different types of disasters. For example, organizations typically have plans for responding to disasters that can hit any organization, such as a fire or a crippling cyber-attack. Organizations will also have other plans that are based on local risks.

These additional plans address weather and nature-based events such as floods, tornadoes, hurricanes, cyclones, and earthquakes. While it’s difficult to predict exactly when these events will occur, reviewing the history of an area can predict the likelihood that one of these events will occur at some point in the future. For example, no one should be surprised if a tornado touches down in Oklahoma during May. Similarly, no one should be surprised if a hurricane threatens land bordering the Gulf of Mexico during September or October.

Comparing a BCP and a DRP

It’s important to recognize the differences between a BCP and a DRP. Many people combine them as though they are synonymous, but they aren’t. In short, the BCP has a much wider scope and helps an organization continue to operate. In contrast, a DRP is a part of the BCP with a primary purpose of restoring a system to operation after an incident results in a major failure.

For example, if an organization is in the midst of a disaster and needs to move operations to an alternative location, the BCP would provide the details on the alternative location and what business functions it will perform. After the disaster occurs, the DRP would provide the details on how to restore operations for specific business functions.

Even though a BCP and a DRP are not the same thing, you may run across documentation that treats them as though they are the same. However, (ISC)2 documentation distinguishes between the two.

Restoration Planning

A key part of business continuity planning is restoration planning. Putting the concepts together, they typically occur in the following order:

• Identify critical business functions The BIA provides this information. Additionally, the BIA identifies the systems that support these critical business functions. For example, an online website might include one or more web servers, a backend database, Internet access, and a supporting network infrastructure.

• Identify restore targets The BIA identifies the MAO, and personnel use this to identify the RTO (and RPO if relevant).

• Create plans to restore systems These plans identify how to restore systems supporting critical business functions within the required times.

These plans need to be extremely clear and detail the exact order of restoration. For example, consider the online website with a backend database hosted on a database server. If the web application expects to connect with the database, it might have unexpected problems if it cannot connect to it. If that’s the case, restoration plans might require technicians to restore the database server first, and then restore the web server. If the database is hosted on a group of servers within a failover cluster, the failover cluster might require servers to be restored in a specific order to ensure the failover cluster remains operational. Similarly, if the website is hosted within a load-balancing cluster of multiple servers, the cluster might require technicians to restore these servers in a specific order.

All of this might be common knowledge to the technicians and administrators who maintain these systems. However, you never know if these technicians and administrators will be available to restore the systems during a disaster. When the restoration plans provide clear directions on what to restore, in what order to restore it, and how to restore it, it makes it easier for any technician or administrator to complete the restoration in the shortest amount of time.

Testing and Drills

The first draft of any plan is rarely perfect. However, testing helps identify the problems so that they can be resolved before an actual disaster. NIST SP 800-84, Guide to Test, Training, and Exercise Programs for IT Plans and Capabilities, provides some excellent guidance on testing methodologies. It discusses tabletop exercises and functional exercises in-depth.

• Tabletop exercises These are discussion-based exercises where personnel meet in a conference room or classroom setting. A facilitator presents a scenario such as a hurricane or tornado and asks the exercise participants questions related to their roles. Talking through the scenario gives participants a better chance to identify potential flaws in the written plans.

• Functional exercise Personnel actually perform the steps outlined in the plan as a method of validating the plan. Functional exercises can be focused on specific elements of a plan or be very broad in their scope. For example, you can give a technician a plan to restore a database server and determine if the technician is able to restore it on a test server using the plan. The actual database server remains online, so the test does not affect actual operations. The exercise can also encompass a full-scale exercise designed to address all the plan elements. While it is only a simulation, it allows personnel to perform their roles as they would in an actual emergency.

In some cases, plans require personnel to take specific actions. A classic example is a fire. If a fire occurs, personnel should exit the building using a predefined path, which helps the maximum number of people exit the building in the shortest amount of time. A simple way to test this type of plan is to hold a drill. The drill requires personnel to respond as if the emergency is occurring. In the case of a fire drill, people hear the fire alarm and exit the building. Fire departments are often happy to participate in these types of drills and provide feedback to the organization on how to improve their plans.

Alternative Locations

If an organization determines that it must be able to continue operations even if a location suffers a catastrophic failure, it designates an alternative location. For example, banks and investment companies need to provide access to customer data even if a weather event (such as a tornado, flood, or hurricane) causes so much damage to one location that they can no longer operate at that location.

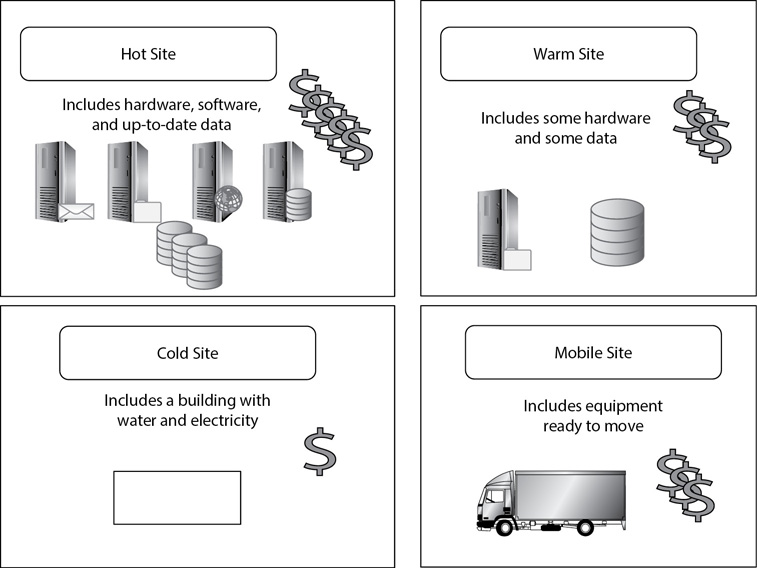

Alternative locations include hot sites, cold sites, warm sites, and mobile sites. Figure 12-6 provides an overall view of each of these alternative location types, and the following sections explain them in more depth.

Figure 12-6 Comparison of alternative locations

Hot Site

A hot site includes all the resources necessary to take over operations of another location in a very short time, typically within an hour and sometimes sooner. A hot site includes hardware such as servers and the network infrastructure, up-to-date data, and personnel to manage the functions of the alternative location.

Hot sites are valuable if an organization needs to prepare for a catastrophic failure that can occur at any time. For example, many banks and investment companies have hot sites ready to take over in case of major incidents, such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Organizations that operate in earthquake or tornado zones often need to have hot sites available far away from the primary location. Hot sites are the most expensive of the alternative location types, but they are the easiest to test, because everything is in place.

It’s rare for a hot site to be used only as an alternative location for an organization. Instead, the organization typically uses it for less critical operations the majority of the time, but keeps it in a ready state to take over critical operations at a moment’s notice. For example, the organization could use the location to provide basic customer services, but also host the equipment and infrastructure as a hot site. If an emergency requires the organization to activate the hot site, personnel at the alternative location scale back customer services temporarily and dedicate more resources to take over for the primary location. As additional personnel arrive at the hot site, it will eventually assume all operations.

Similarly, regional locations often have the capability of taking over another region’s services. For example, an organization can have major locations in the western and eastern parts of a country. If either region’s location fails, the other location can take over the critical operations of the failed location.

Cold Site

A cold site is a building with a roof, running water, and electricity. It doesn’t include the necessary hardware, software, or personnel. In the event of an emergency, personnel move all the resources to the cold site location, hook it up, and configure the site for operation.

It’s difficult to test a cold site because nothing exists at the location. However, a cold site is significantly cheaper to maintain than other types of sites.

Warm Site

A warm site is a compromise between a cold site and a hot site. The organization makes compromises with costs and time. Instead of ensuring that the site can be activated within minutes, the organization may decide that 24 hours’ notice is enough to bring it online.

For example, an organization may operate in a hurricane zone. Because hurricanes travel relatively slowly, communities often have more than a day’s notice of a possible hurricane landfall. When a storm is approaching, the organization can use the time to activate a warm site. This includes deploying personnel to the warm site and updating all the data.

Mobile Site

When an organization doesn’t want to use a dedicated location as an alternative location, it can create a mobile site. For example, it’s possible to set up the inside of a storage container as an alternative location. These are the same storage containers that 18-wheeler tractor-trailers use to haul goods, and they are as easy to move as any other loads hauled over the highways.

Organizations outfit these storage containers with all the equipment needed to support critical operations. If an emergency requires activating the mobile site, the organization moves it to the desired location and hooks it up to power. Depending on its needs, the organization might use an external heating and ventilation system, or bring one with the container and then mount it on the roof or outside the storage container. Similarly, the organization might connect directly to a broadband Internet service provider (ISP) for Internet access at the mobile location, or use a satellite or cellular connection.

Mobile sites like this will have all the necessary equipment, but the software and data are typically out of date. When the mobile site reaches its destination, personnel will ensure that the equipment is up to date with all appropriate patches and approved changes and that the data is up to date.

Mobile sites don’t have to be as elaborate as a fully equipped storage container. For example, one small company in Virginia Beach has a simpler mobile site plan. When a hurricane is approaching, the owner packs the company’s primary server into her car and drives west. When she settles somewhere, she plugs a USB wireless adapter into the server, configures her phone as a personal hotspot, and uses it to provide Internet access for the server.

The cost of a mobile site is similar to the cost of a warm site—somewhere in the middle of a cold site and a hot site. The actual cost varies depending on what an organization chooses to use for its mobile site. Clearly, the packed storage container will be much more expensive than the owner’s car, smartphone, and a single server.

Identifying Security Organizations

Several security organizations exist that provide different levels of assistance and documentation for IT security personnel. It’s worthwhile knowing about some of these organizations and their available documentation.

NIST

Several chapters within this book mentioned the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST includes a Computer Security Division and an Information Technology Laboratory (ITL). The organization regularly performs research in the area of information technology in direct support of federal agencies. However, NIST uses federal funds to perform this research, so it makes this research publicly available as Special Publications (SPs).

SP 800 Documents

The SP 800 series of documents includes over 100 well-researched documents on a wide range of IT security topics, including cloud computing, risk management, intrusion detection and prevention systems, protection of wireless transmissions, protection of personally identifiable information (PII), and much more. You can view a full list of these documents (and download any of them) at https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/sp800.

Some of the documents that directly relate to security policies and continuity planning include

• SP 800-18 Guide for Developing Security Plans for Federal Information Systems

• SP 800-30 Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments

• SP 800-34 Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems

• SP 800-37 Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy

• SP 800-41 Guidelines on Firewalls and Firewall Policy

• SP 800-53 Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations

• SP 800-58 Security Considerations for Voice Over IP Systems

• SP 800-61 Computer Security Incident Handling Guide

• SP 800-64 Security Considerations in the System Development Life Cycle

• SP 800-77 Guide to IPsec VPNs

• SP 800-83 Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops

• SP 800-84 Guide to Test, Training, and Exercise Programs for IT Plans and Capabilities

• SP 800-94 Guide to Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDPS)

• SP 800-97 Establishing Wireless Robust Security Networks: A Guide to IEEE 802.11i

• SP 800-100 Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers

• SP 800-111 Guide to Storage Encryption Technologies for End User Devices

• SP 800-113 Guide to SSL VPNs

• SP 800-115 Technical Guide to Information Security Testing and Assessment

• SP 800-122 Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII)

• SP 800-123 Guide to General Server Security

• SP 800-124 Guidelines for Managing the Security of Mobile Devices in the Enterprise

• SP 800-127 Guide to Securing WiMAX Wireless Communications

• SP 800-183 Networks of ‘Things’

Cybersecurity Framework

NIST published Version 1.1 of the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity in April 2018. Security personnel commonly refer to this as the Cybersecurity Framework (CSF). It focuses on using business drivers to guide cybersecurity activities, while considering cybersecurity risk as part of an overall risk management process. The CSF has three primary elements: Framework Core, Implementation Tiers, and Framework Profiles.

The Framework Core is a set of cybersecurity activities, desired outcomes, and references that can be applied to most organizations. It includes industry standards, guidelines, and best practices within five primary Framework Core Functions: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover. Each of these functions can be applied to different categories of a cybersecurity program.

Table 2 (a comprehensive 19-page table) lists between three and six categories within each of these functions. As an example, the Protect function includes a Data Security category. It includes the following eight subcategories, which represent best practices:

• Data-at-rest is protected.

• Data-in-transit is protected.

• Assets are formally managed throughout removal, transfers, and disposition.

• Adequate capacity to ensure availability is maintained.

• Protections against data leaks are implemented.

• Integrity checking mechanisms are used to verify software, firmware, and information integrity.

• The development and testing environment(s) are separate from the production environment.

• Integrity checking mechanisms are used to verify hardware integrity.

Each subcategory includes multiple references that personnel can use to get a better understanding of the topic. Personnel can identify if they are currently implementing this best practice, and if not, use the references to help them improve their current practices.

The Implementation Tiers can be used to identify how an organization views cybersecurity risk. The Tiers are

• Tier 1: Partial The lowest tier, Tier 1 indicates that risk management processes are not formalized and there is a limited awareness of cybersecurity risk.

• Tier 2: Risk Informed This tier indicates that risk management practices are in place but may not be followed. Personnel may be aware of risk, but an organization-wide approach to managing risk has not been established.

• Tier 3: Repeatable This tier indicates that risk management practices are formally approved and documented in policies. Personnel have the knowledge and skills necessary to perform their roles. Personnel at all levels of leadership regularly communicate to each other on cybersecurity risk.

• Tier 4: Adaptive The highest tier, Tier 4 indicates that the organization adapts its practices based on previous and current cybersecurity activities. It has processes in place for continuous improvement. Executive management evaluates cybersecurity risk in the same manner that they evaluable financial risk.

The Framework Profiles can help an organization ensure that the Functions within the Framework Core are aligned with the business requirements. As an example, cybersecurity personnel can evaluate all the Categories and Subcategories within the Framework Core and identify which tier they are in. This can provide the organization a baseline.

Personnel can then work with senior management to identify a target profile based on senior management’s vision, risk tolerance level, and amount of resources management is willing to devote to cybersecurity.

Monthly Bulletins

NIST also publishes monthly bulletins available here: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/itl-bulletin. Each monthly bulletin focuses on a single topic of interest related to computer security. For example, the March 2018 bulletin, titled “Safeguards for Securing Virtualized Servers,” summarizes technical guidelines related to securing hypervisor platforms.

ITL vs. ITIL

The Information Technology Laboratory (ITL) is not related to ITIL. ITIL (formally known as the Information Technology Infrastructure Library) is a group of books documenting best practices for IT management. The United Kingdom Office of Government Commerce created the original ITIL books, but ITIL has gone through several changes over the years. Axelos, Ltd. currently owns all of the ITIL intellectual property, and it licenses the use of ITIL materials to other orga-nizations. Axelos also accredits organizations as licensed Examination Institutes for the ITIL-related certifications.

In contrast, a U.S. government entity creates the ITL documents, which are freely available to anyone. The SP 800 series of documents are public-domain documents rather than intellectual property. Additionally, ITL doesn’t sponsor any certifications.

US-CERT

The United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) provides response support and defense against cyber-attacks for several government entities in the United States and for some industry and international partners. It is operated as part of the National Cyber Security Division (NCSD) of the Department of Homeland Security as a public/private partnership.

US-CERT sponsors the National Cyber Awareness System, which includes several methods of providing information to users and technical experts. Chapter 6 mentioned several of the newsletters that US-CERT publishes, and you can sign up for any of them here: https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas.

SANS Institute

While the SANS Institute is a private institution that sponsors other security certifications and sells training for these certifications, it also publishes some free resources. For example, the SANS Reading Room includes more than 2,780 free white papers on a wide variety of computer security topics. You can access the SANS Reading Room here: www.sans.org/reading-room/.

SANS also sponsors the Internet Storm Center, mentioned in Chapter 6. The Internet Storm Center monitors threats related to malware and provides free information via diaries (https://isc.sans.edu/diaryarchive.html) and podcasts (https://isc.sans.edu/dailypodcast.xml).

CERT Division

The first CERT Coordination Center was created at Carnegie Mellon University in response to the Morris worm that struck in 1998, and was later renamed as CERT Division. It is a federally funded program located in the Software Engineering Institute (https://www.sei.cmu.edu/about/divisions/cert/index.cfm/). The CERT Division works closely with the government, industry, law enforcement, and academia personnel to improve security of computer systems and networks. You can read more about it here: https://www.sei.cmu.edu/about/divisions/cert/index.cfm.

Chapter Review

A security policy is a written document, authoritative in nature, that provides a high-level view of the security goals for an organization. External standards may influence the security policy, but the organization decides what standards to follow. Personnel develop procedures based on the guidance from the security policy.

Senior-level management should create, or at least endorse, the organization’s security policy. Once the security policy is created, personnel within the organization implement and enforce it. Users must be made aware of the contents of the security policy through training, warning banners, posters, and other awareness methods, and they should be asked to read and sign an acceptable use policy. It’s common to review a security policy periodically, such as once a year or after a security incident.

Business continuity plans (BCPs) include processes and procedures to prevent the loss of mission-critical services. A BCP starts with a business impact analysis (BIA) and includes one or more disaster recovery plans (DRPs). It’s important to recognize that a BCP is not the same as a DRP, but a DRP is often a component of a BCP.

The BIA identifies the maximum acceptable outage (MAO) time (also called maximum tolerable downtime, or MTD) for critical services and systems. If an outage for one of the critical services or systems exceeds this time, it impacts critical business functions. The MAO drives the recovery time objective (RTO), or the maximum amount of time that the organization can take to restore a critical service or system. The recovery point objective (RPO) refers to the point in time to which a database needs to be recovered if the system fails.

A DRP provides the steps required to restore a system after an outage. Organizations test both BCPs and DRPs using various testing methods. Tabletop exercises allow personnel to talk through the steps of a given scenario. Functional exercises simulate an event and allow personnel to walk through the steps of a given scenario.

Some BCPs require the use of alternative locations. A hot site includes all the hardware, software, and up-to-date data required to take over operations at a moment’s notice. A cold site includes a roof, water, and electricity, but little else. A warm site is a compromise between a hot site and a cold site. Some organizations use a mobile site instead of a fixed location, which allows the organization to move its operations to another location during an emergency.

NIST includes a Computer Security Division and an Information Technology Laboratory. The ITL has published over 100 Special Publications in the SP 800 series on a wide range of IT security topics. All of these special publications are available for free download here: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/sp800. Other organizations that provide security-related materials include US-CERT and the SANS Institute.

Questions

1. Of the following choices, which provides the highest level authority within an organization?

A. Standards

B. Policies

C. Guidelines

D. Procedures

2. Which of the following choices best describes an organization’s security policy?

A. An authoritative written document that identifies an organization’s overall security goals

B. A nonauthoritative written document that identifies an organization’s overall security goals

C. A technical control that mitigates risks

D. A baseline used to ensure that systems are secure when deployed

3. Which of the following best describes the purpose of a security policy?

A. Ensures personnel understand their responsibilities

B. Ensures personnel use strong authentication

C. Informs personnel of management priorities related to security

D. Provides guidance on management controls

4. An organization wants to ensure that users are aware of their responsibilities related to the use of IT systems. What should the organization create?

A. A video monitoring system

B. An audio monitoring system

C. An acceptable use policy

D. An account lockout policy

5. Sally notices that Homer appears to be stealing from the company. What should Sally do?

A. Confront Homer

B. Ignore the activity because it doesn’t concern her

C. Call the police

D. Report the activity to a manager

6. Which of the following choices are effective methods of ensuring that employees know the relevant contents of an organization’s security policy? (Choose all that apply.)

A. Providing training

B. Using warning banners

C. Using posters

D. Storing the policy in the company vault

7. An organization has a security policy in place. What can personnel within the organization do to ensure it remains relevant?

A. Perform audits

B. Perform training

C. Review it

D. Test it

8. Which of the following is the most important element of business continuity planning?

A. Support from senior management

B. Availability of a warm site

C. The backup plan

D. Cost

9. What is the purpose of a BIA?

A. To identify recovery plans

B. To drive the creation of the BCP

C. To test recovery plans

D. To identify critical business functions

10. Which one of the following is a valid step to perform during a business impact analysis?

A. Identify alternative locations

B. Create a plan to restore critical operations

C. Identify resources needed by critical business functions

D. Identify minimum outage times for key business services

11. What is MTO in relation to business continuity planning?

A. Minimum time for an outage

B. Maximum time for an outage

C. Minimum tolerable outage

D. Maximum tolerable outage

12. Which of the following best describes maximum tolerable downtime?

A. The maximum amount of downtime before a business loses viability

B. The point in time in which a failed database should be restored

C. The maximum amount of time that can be taken to restore a system or process

D. The minimum amount of time that can be taken to restore a system or process

13. What is RPO in relation to business continuity planning?

A. Restoring potential outage

B. Recovery point objective

C. Restoration process option

D. Recovery process options

14. What is RTO in relation to business continuity planning?

A. Recovery terminal objective

B. Recovery time objective

C. Recovery tolerable outage

D. Recovery tolerable objective

15. An organization’s location has been hit by a tornado and the organization is moving to an alternative location. What provides the direction for this action?

A. BIA

B. BCP

C. DRP

D. Hot site

16. An organization decides to designate an alternative location to be used in case of an emergency. The organization doesn’t need anything other than an open building with water and electricity. What type of site best meets this need?

A. Hot

B. Warm

C. Cold

D. Distant

17. An organization decides to designate an alternative location for operations during a disaster. The site must be up and operational within minutes of an outage at the primary location. What type of site best meets this need?

A. Mobile

B. Cold

C. Warm

D. Hot

18. An organization is updating its business continuity plan (BCP) and wants to implement an alternative location that is the easiest to relocate. What type of site best meets this need?

A. Cold

B. Hot

C. Mobile

D. Warm

19. Of the following choices, what is a U.S. government entity that regularly publishes Special Publications (known as SP 800 series documents) related to IT security?

A. ITIL

B. NIST

C. CERT Division

D. US-CERT

20. Which of the following organizations provides regular cybersecurity alerts about current security issues, vulnerabilities, and exploits as part of the U.S. National Cyber Awareness System?

A. ITL

B. NIST

C. CERT Division

D. US-CERT

Answers

1. B. Policies are high-level documents and provide authoritative direction. Standards can influence a policy, but an organization chooses what standards to follow. Guidelines provide recommendations, but they are not mandatory. Personnel create procedures based on the policy.

2. A. A security policy is an authoritative (not nonauthoritative) written document that identifies an organization’s overall security goals. It is a management (or administrative) control, not a technical control or a baseline; however, technical controls and baselines are created based on the direction from the security policy.

3. C. Of the choices, the best description is that the security policy informs personnel of management priorities related to security. The other answers provide some specific goals of a security policy but do not address the overall purpose. An acceptable use policy helps ensure personnel understand their responsibilities. Technical controls ensure personnel use strong authentication, but a security policy covers more than just technical controls. Similarly, a security policy provides guidance on more than just management controls.

4. C. An acceptable use policy (also called an acceptable usage policy) lets users know what is acceptable use of computer equipment and networks. Monitoring systems ensure users follow policies, but they don’t ensure users know the policy. Account lockout policies lock out users after too many failed password attempts.

5. D. An employee’s loyalty should be to the organization, so Sally should report this activity to a manager or supervisor. An organization’s ethics policy often includes procedures for reporting these types of incidents. Confronting Homer may not solve the problem but instead may result in Homer causing problems for Sally, especially if Homer is stealing from the company. Because continued employment is based on the success of an organization, losses are the concern of every employee. The organization should make the decision of whether or not to call the police.

6. A, B, C. Providing training, using warning banners, and using posters are all effective methods of ensuring that employees know the relevant contents of a security policy. If the security policy is stored in the company vault, it won’t be accessible to employees.

7. C. A security policy should be reviewed on a regular basis (such as once a year or after a security incident) to ensure that it is still relevant. Audits help to prove that the security policy is being used and enforced. Training ensures that people know the contents of the security policy. It’s appropriate to test a BCP or a DRP, but not a security policy.

8. A. Of the available answers, the most important element is support from senior management. While an organization might decide it needs a warm site, not all BCPs require warm sites. A security policy may mandate the creation of backup plans, but this is separate from the BCP. The cost is a concern, but the requirements drive the cost, and without support from senior management, business continuity planning may not receive any funding.

9. D. The business impact analysis (BIA) identifies critical business functions and is a part of the BCP. Personnel create recovery plans later in the process, after creating recovery strategies. The BCP drives the creation of the BIA, not the other way around as suggested by answer B. You can only test the plans after personnel have created them.

10. C. A core goal of a BIA is to identify critical business functions and the resources needed by these critical business functions. Identifying alternative locations is part of a business continuity plan (BCP). A disaster recovery plan (DRP) is a plan to restore critical operations. A BIA does identify maximum acceptable outage times, but not minimum outage times.

11. D. The maximum tolerable outage (MTO), sometimes called maximum allowable outage (MAO) or maximum tolerable downtime (MTD), identifies the maximum amount of time that a system can be down before critical business functions are affected. The T does not represent time, and the M does not represent minimum.

12. A. The maximum allowable outage (MAO), sometimes called maximum tolerable downtime (MTD), indicates the maximum amount of downtime a business can tolerate and still maintain viability as a business. Recovery point objective (RPO) indicates the point in time to which a failed database should be restored. Recovery time objective (RTO) represents the maximum amount of time that can be taken to restore a system or process after an outage. MTD is not related to minimum timeframes.

13. B. RPO represents recovery point objective and indicates the point in time to which a failed database should be restored. The other answers are not valid terms for RPO within business continuity planning.

14. B. RTO is an acronym for recovery time objective and represents the maximum amount of time that can be taken to restore a system or process. The RTO is derived from the maximum allowable outage (MAO). The other answers are not valid terms for RTO within business continuity planning.

15. B. The business continuity plan (BCP) provides direction for moving to an alternative location after a disaster; the primary purpose is to continue to provide critical business functions. The business impact analysis (BIA) helps an organization identify what functions are critical. The disaster recovery plan (DRP) has a narrower focus and helps an organization recover one or more systems after the disaster has passed. A hot site is a possible type of alternative location, so it doesn’t provide direction for the action.

16. C. A cold site is a building with water and electricity and nothing else (such as no computer equipment or data). A hot site includes everything and is ready to take over operations within a short time after an outage. A warm site is a compromise between the two. A distant site isn’t a valid term for an alternative location.

17. D. A hot site includes everything and is ready to take over operations within minutes after an outage. A mirrored site (not available as an answer) is a type of hot site that can take over operations almost immediately. A mobile site will take much longer to relocate and set up. A cold site is a building with water and electricity, and it would take much longer to become operational. A warm site is a compromise between a hot site and a cold site and takes longer to become operational than a hot site.

18. C. A mobile site is the easiest to relocate. Hot, cold, and warm sites use a designated location that the organization either purchases or leases.

19. B. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) publishes documents in the SP 800 series related to IT security. ITIL is a United Kingdom project. CERT Division is a federally funded program located in the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, and the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) provides response support and defense against cyber-attacks. While CERT Division and US-CERT publish documents related to IT security, they don’t publish SP 800 series documents.

20. D. The U.S. Computer Emergency Response Team (US-CERT) manages the National Cyber Awareness System, which provides cybersecurity alerts, bulletins, tips, and updates. The other organizations provide information, but not alerts through the National Cyber Awareness System.