To realize the true potential of Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), we need to be able to explain the value that SSI represents to organizations and people. We need to provide a compelling, understandable, and truthful account of what SSI can mean, so our audience sees the value in it for themselves. This is as essential to SSI’s success as the technology that underpins it. We selected this as the first chapter in part 4 because it provides guidance on how best to communicate the value of SSI to business leaders. It is also important for technologists, who can use these ideas to better understand business goals. The author, John Phillips (of 460degrees, based in Australia), speaks from experience—he is one of the world’s leading communicators about the value of SSI. Lucky enough to start his career working with international space agencies and living in a number of countries, John is now directing his efforts and passion toward better digital trust for all.

One of the key pivot points that helped our understanding of how to explain SSI occurred while working with a group of undergraduate students at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia. We had given the final-year design class a challenge for their capstone project (the last major project of their degree): how to design an approach to SSI and digital wallets for the people of Melbourne. The project ran for most of the second semester, with the students working in groups on the challenge. By the end of the project, the students had come up with brilliant ideas, and we learned at least as much from the experience as they did.

During an early discussion, one of the students shared the challenge she’d had at home during the week when trying to explain SSI to her father, a 50-something Australian who had worked on the land for most of his life. “He just didn’t get it! How can you explain this stuff to someone like my dad?”

We left that meeting wondering how best to answer that question. We experimented with ways to explain SSI (not our first visit to this challenge) and started to look through the items we had in the innovation/design thinking craft drawer in the office. We used a familiar use-case story (renting a property) and animated it using foam figures, hand-written cards, envelopes, and popsicle sticks.

For the next few days, we carried this kit with us wherever we went and tried it out on every person we had coffee with or met in a meeting. We got better at telling the story as we practiced. We found that despite (or perhaps because of) the “craft kit” qualities, the approach worked well—people got it. The conversation would become animated, and people picked up the items and moved them around as they asked questions. At our next meeting with the students, we excitedly showed them our new way of explaining SSI—an approach that could even work with a retired sheep shearer (we hoped).

The experience of working with these students, the challenges and questions they raised, and our own experiences working with the business community made us realize that we needed a way to explain SSI that was simpler, more compelling, and able to reach diverse audiences. This is an essential problem for the SSI community to solve. No matter how much technical elegance it has, SSI will be successful only if we can convince people and organizations to use it—and if we can convince organizations to, quite literally, buy into it.

As the Swinburne students observed, understanding SSI is no easy matter. The technology and underlying philosophy are rich and complex. Understanding why it was designed this way, how it works, and what it can and can’t do takes time. We can’t expect everyone to dive deep enough to understand all the technical facets of SSI, nor should we.

So how, then, can we motivate the very adoption we need for SSI to be successful? The answer to this challenge is understanding what SSI can mean for organizations and people in the context of their own lives and markets—the value of SSI to them.

The next few sections explain how we learned, through a series of experiments, what works and what doesn’t work when explaining SSI. The chapter concludes with recommendations about how to explain SSI in any given situation.

18.1 How might we best explain SSI to people and organizations?

Let’s explain the technology. After all, it is pretty damn cool when you get to understand it—and surely everyone else will see it that way if we can just explain it well enough.

18.1.1 Failed experiment 1: Leading with the technology

Most SSI converts start by exploring the technology, often because that is their core expertise. We explain the math, the software, the standards, and all the bits that make SSI work. This explanation is impenetrable to most people in a short meeting and also fails to clarify the “why” of SSI for them: how it can make their lives and/or businesses better.

At best, a technology-first approach will work in only a few instances with a handful of people. Of course, it is essential that the technology works—and that there is proof that others can peer review. However, when we want to discuss the opportunity SSI presents with people and organizations, most of the time they don’t have the time or technical background to understand the underlying technology.

NOTE For those already steeped in SSI: you would do well to remember how long it took you to first understand the technology. I doubt it was a one-hour meeting.

Here are two key reasons why leading with the tech is not the best approach:

-

It’s overwhelming. Explaining SSI by explaining the technology is like trying to explain the internet by describing the Request for Comments (RFC) documents that define the standards in the TCP/IP suite. Most people just want to know what using a browser can let them do, not how RFC 2616 works (the RFC for the HTTP protocol).

A lot of work has been done by many very good engineers over several years to develop the SSI framework—and that work continues. You can’t expect your audience to “get it” in the few minutes you have to explain the value of SSI.

-

It’s irrelevant. Consider your audience. Organizations exploring SSI typically have a mix of people, interests, and experience in the room—technologists, marketers, product owners, and business executives. Each of them has a personal and professional mental model of digital identity and digital trust—and the technical and commercial environments in which those things exist. In addition, they have a collective view built around their own way of handling digital identity and trust in their organization.

For the majority of the audience, the technology part is a distraction at best. They expect the tech to work—otherwise, they wouldn’t take the time to look into it—but they are far more interested in the problems it will solve for them.

18.1.2 Failed experiment 2: Leading with the philosophy

Rather than leading with the tech, we could start by explaining the principles and philosophy of self-sovereign identity. After all, that’s what many of us personally find so attractive. We might feel it is important to share the underlying principles and history since they are so rich and interesting and deeply woven into the authentic fabric of SSI. It really matters that we believe SSI can make the world a better place, protect privacy, strengthen democracies, and protect us against the evils of surveillance capitalism.

What we’ve found when embarking on these discussions is that the words self, sovereign, and identity come loaded with personal meaning and interpretations—some of which are quite often radically different for each individual in the room. Each of these terms could be the subject of an entire philosophy or humanities course. (Many SSI adherents have spent considerable time seeking alternative terms that better describe the essence of SSI without such strong connotations—or at least with less risk of distraction or misinterpretation.)

Our experience is that, with almost all organizations, the philosophy of SSI is interesting but almost certainly irrelevant to their main interest, which is the benefits SSI brings to their organization. Concentrate on that first before making any attempt to explain why SSI can be a force for global good. Attempting to explain the philosophy behind SSI and the meaning of the terms in the context of a short meeting risks delay and derailing the conversation that will lead to adoption.

Note There is a secondary risk, too. Many of us who are drawn to SSI are passionate about this work and the meaning it gives to our lives. If we spend too much time focusing on this message, we risk being seen as idealists and perfectionists rather than pragmatic and focused on business value.

So if we want SSI to be as successful as we believe it can be, we need to focus on the benefit to each adoptee while remaining true to the principles and philosophy of SSI.

18.1.3 Failed experiment 3: Explaining by demonstrating the tech

This approach is attractive since we’re “proving” that what we’re talking about exists and works. Except we’re not, really.

Demonstrating working technology is an expected part of any process of convincing someone that something is real and worth having/using. It will be important at some point in their discovery process. However, if they are truly skeptical, they’ll know you can give whiz-bang demos that can make almost anything look good. After all, nowadays, it’s easy to make a presentation deck behave like a web application.

In addition, all demonstrations are by necessity simplifications. They must use stub websites or mock interactions. So skeptics often remain unconvinced because you haven’t done the hard part of making the technology work in production.

The other, perhaps more curious, reason that showing the technology doesn’t impress as much as we’d hope is that people expect the tech to work. Hence it’s not a surprise when it does. After all, we wouldn’t be showing it to them if it didn’t work, would we?

Furthermore, part of the power of SSI is that the magic happens invisibly in the math and communication protocols that underpin it. That’s the beauty of it—and what makes it usable. Surfacing that magic by instrumenting the code and showing what is (and isn’t) being read and written on the ledger, for example, risks making the technology look complex.

Bottom line: demos have a role to play at some point, but first your audience needs to be motivated by the benefits. Then they need to know where to look for the magic when you demonstrate, so you have to narrate the parts they can’t actually see.

18.1.4 Failed experiment 4: Explaining the (world’s) problems

It is an accepted truth among SSI practitioners that the digital world we all live in has serious and growing problems with privacy and trust. The concepts of identity theft, honey-pots for hackers, toxic stores of personal identifying information, privacy erosion, and surveillance capitalism are increasingly common in the mainstream media [1]. These issues are some of the drivers for the development of SSI.

We might expect that the people and organizations we talk to about SSI understand these issues, at least to some extent, and we can certainly increase their awareness during our discussion. However, to put it bluntly, this is most likely irrelevant to the current conversation. While we would like to help achieve a peaceful, safe, and privacy-enabled future, this isn’t on the strategic goals list of many organizations (unless you’re talking to people like the UN).

There are, of course, ways to make this element meaningful to the audience. For example, we can focus on the organization's use of customer data and its honey-pots for hackers. We can talk about how SSI can enhance the digital trust between the business and its customers and partners. We can talk about risk reduction and how the company can reduce its compliance burden or become compliant. But these are the business’s problems; and if they also happen to reflect the world’s problems, so much the better if the business can solve them in its own domain.

18.2 Learning from other domains

Fortunately, we can take ideas from many other domains to help us explain the value of SSI to people and organizations. Some of the key sources are the following:

-

Teaching —Clearly, what we are aiming to do has an element of teaching, and there is a wealth of research and materials to lean on.

-

Human-centered design —Many resources are available on this topic from universities and organizations like IDEO.

-

(Professional) story telling —Human beings are wired to understand and remember using stories or anecdotes. Explaining through a story structure means the subject will be easier for the audience to understand and remember.

-

Pitch decks —Another easily accessible wealth of advice and templates centers on how to explain (that is, sell) your new, wonderful (possibly patented) idea to an audience to try to convince them to invest.

-

Consulting processes —All consulting companies have processes of one form or another that describe how they explain the results of their work to the client that paid for them. The details vary, but the intent is much the same: explain an issue, and present a course of action to be taken. A classic example is The Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing and Thinking (Barbara Minto; Prentice Hall, 2008).

-

Behavioral economics —A growing body of work and practitioners are looking at why people make the decisions they do and what influences those decisions. Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Richard Thaler, Dan Ariely, and others have developed models of understanding around how we are all “predictably irrational” (to use Ariely’s phrase).

-

Professional sales processes —We should not be shy about the fact that we are selling the idea of SSI. High-value, high-stakes sales professionals follow a framework for “honorable” selling, where trusted relationships are established and maintained and selling isn’t a once-and-done (or once-and-run) activity. This means taking the time to explore whether what we have to offer (SSI) is good for the organization or person we are talking to and sincerely digging into learning how that person or organization might best go about adopting SSI.

18.3 So how should we best explain the value of SSI?

The lessons we learned from trying each of the approaches discussed earlier—in person, in writing, in presentations, and in demonstrations—helped us better understand how to explain SSI in a business context. Ultimately, the design students at Swinburne helped us to think of this challenge as a design problem. In other words, think of “designing” your explanation of SSI for the business you want to talk to.

Using a design framework, we can identify the key elements that we need to focus on:

-

Empathize. Understand your audience: their market, their business, and the people in the organization. Whom are you seeing? What is their professional and personal interest likely to be? What sorts of issues/opportunities are they likely to be troubled by and interested in?

-

Define the problem(s). Select the issues you think they can solve with SSI and the opportunities they can realize. Define these in simple terms that will resonate with your audience. Use the design thinking “How might we ...” structure.

-

Ideate. Develop your idea about how to solve the problem(s) you identify. Test these for their practicality and relevance. Do they make business sense? Do they solve a problem worth solving or deliver an outcome worth having? Does the investment look reasonable against the return?

-

Select . Choose the ideas that make the most sense, ideally by pre-testing them with people from the company you are selling to (or someone who knows the organization well).

-

Prototype. Select materials, and build the elements you need. These might be presentation decks, craft supplies, software, videos, or other ways you can explain the ideas.

-

Test. Try the approach with people in your organization, learn from their reactions, and revisit earlier stages.

-

Launch. Share with the business you want to talk to (and learn from this step, too!).

The lessons learned at each of these stages might require revisiting earlier assumptions. Developing the best approach to explain how SSI can add value to a specific business is an iterative process—you are very unlikely to get it right the first time.

18.4 The power of stories

In our experience, there is one consistent approach for explaining the value of SSI to professionals and businesses: tell stories. By this, I mean having a planned narrative, using anecdotes that people can associate with professionally and personally, and making the journey personal, relatable, and meaningful to their business.

Why stories? Because most of us are pre-conditioned to listen to stories. They are part of being human—part of our upbringing and background. For most of us, stories are far easier to remember than lists of facts or take-home points.

We recommend that you use a story architecture even for business stories. Stories typically have an arc like this:

Gifted storytellers can change the order of these points, hint at future reveals, provide unexpected twists, and give the punchline before the background; but for most of us, it is easiest to stick to this order.

Note that I’m saying story, not use case. Yes, a use case can be a story (and most would be better if they were told as stories to give them context and meaning). However, most use cases are dry, depersonalized affairs, devoid of interest for anyone except their narrator. Having a “persona” does not make your use case a story. Give your persona(s) a back story and context, give your use case a plot and a moral, and now you’ve got a story.

18.5 Jackie’s SSI story

Here’s the example we developed when working with the Swinburne University students. This became the story we captured on video for mostly internal purposes (and which eventually caught the attention of the editors of this book).

-

The current world of physical documentation (to get on the same page as everyone in the audience through a shared experience)

-

The current world of our digital lives—full of hidden, and not-so-hidden, problems

We normally tell this in person using props, but since this is a book, we’ll use a cartoon storyboard version of the story.

18.5.1 Part 1: The current physical world

18.5.2 Part 2: The SSI world—like the current physical world, but better

In part 1, we saw Jackie lease her new apartment using documents she owns to prove her identity. That's the world many of us live in right now. In part 2, we're going to see how this process works in an SSI-enabled world. Spoiler alert: it will be like the current world, but better.

To keep the story simple and get to the moral faster, we'll show what Jackie experiences if she already has an SSI digital wallet with a couple of credentials loaded. (The origin story will come later. Doesn't it always?)

18.5.3 Part 3: Introducing the Sparkly Ball1—or, what’s wrong with many current digital identity models

In part 1, we saw Jackie lease her new apartment using documents she owns to prove her identity. In part 2, we showed how SSI can enable a familiar but better version of this process for Jackie and Highly Rated Rentals. In part 3, we talk about the problem with many current digital identity models.

At the moment, in most countries in the world, the primary documents we use for identification are physical. For most of us, items like passports, driver’s licenses, education and training certificates, vaccination records, and other identity-related records are physical documents we store in wallets, drawers, and filing cabinets. Increasingly, however, we need to access services and products online, and for that, we need some form of digital identity.

Let's say Jackie needs a digital identity to access services online from a number of organizations. To get a digital identity, she needs to find an identity service provider of some kind—an organization that can issue a digital identity. While any online organization can create an online identity, to be useful, this identity needs to be recognized and trusted by other organizations.

The degree of trust depends on the provider's reputation, the processes they use, and the legal and social licenses they hold. Digital identity service providers can be government agencies, commercial companies, or non-profit organizations. In Australia, these providers are governmental (such as MyGovID), commercial entities recognized by the government (such as AusPost Digital ID), and social/commercial entities like financial institutions and technology companies (Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, and so on).

The basic process is that you provide the identity service provider (issuer) with a bunch of information about you, and, depending on the checks the provider needs to do, it issues a digital identity for you. Sometimes the checks are quite demanding (proof of citizenship, birth, bank accounts, and so on), and sometimes you just need to prove that you control an email address or a mobile phone number.

The level of proof demanded and verified is one of the factors that determines how strongly that digital identity is linked to you and thus how much trust it conveys when you use it. Once you have the digital identity from the provider, you can use it with other organizations that accept it as proof of identity.

Now, if this were the SSI model, the identity service provider would give you a verifiable credential with a bunch of verified data in it that you could store in a digital wallet of your choice. You could use this when you chose, with whom you chose, showing as much or as little as you chose without the issuer needing to know you're using the credential.

But it's not SSI. It's a legacy digital identity containing a legacy identifier for you.

These legacy systems—whether centralized or federated—give you an identifier and a way for you to prove that identifier was given to you. This proof can be a password or, ideally, a combination of several things (multi-factor). Each time you use the identifier, the receiving organization (verifier) asks the identity service provider to verify it.

Therein lies the privacy issue. Now the identifier you are using is known to both the issuer and the verifier. Using the same identifier across multiple spaces introduces a correlation risk, just like today's problem with tracking cookies on the web.

Once the identifier is authenticated, the receiving organization looks you up in its databases to see what services and resources your identifier can access. The verifier needs to remember all this information about you because it has no other way to know what you are and are not allowed access to on its system. That's a bureaucratic burden for the verifier—and a risk for both of you since if that personal data is hacked, it can be used to impersonate you for identity theft.

Ethical identity service providers try to not watch or learn about what you're doing. They digitally “cover their eyes” (deliberately forgetting connection details) and promise to forget everything they learned within a short period (say, every 30 days). Others might not be so inclined, for the simple reason that their business model motivates them to gather data about you so that they can sell it to others.

But good intentions or no, the problem with identity service providers is that they can’t help being in the loop. So whether they are actively authenticating or passively linking your data trail, your privacy is at serious risk.

That's why we don't like “shared identity” models of any kind, whether centralized, federated, or hybrid. Only by moving to the SSI model where the only party in the loop at all times is you, the individual, can we finally have both strong security and strong privacy.

18.6 SSI Scorecard for apartment leasing

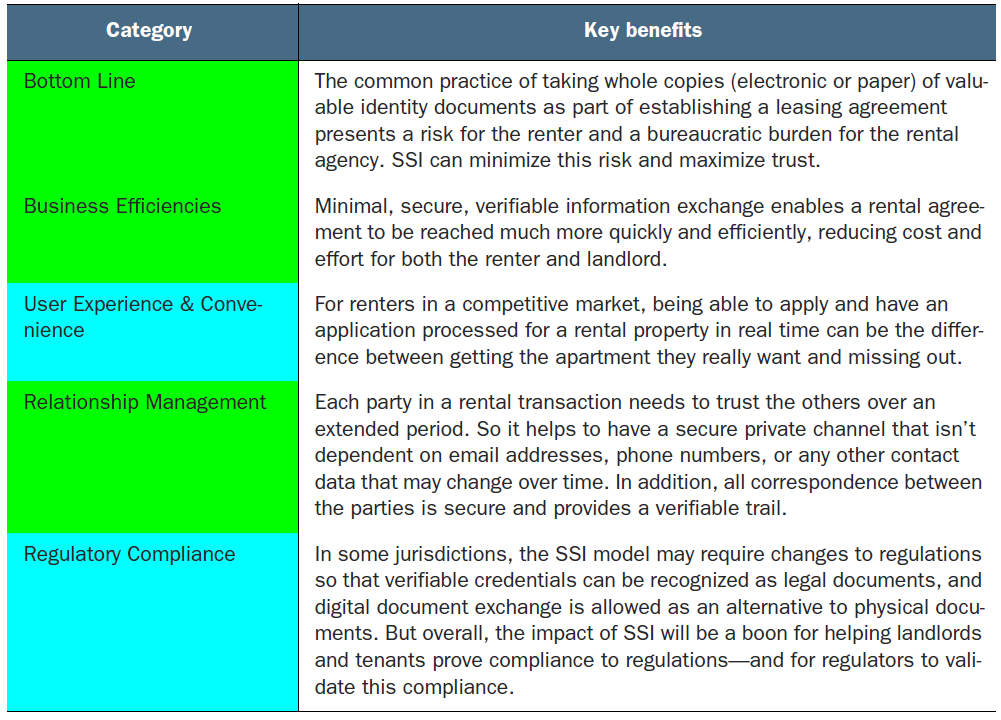

The SSI Scorecard is color-coded as follows:

In each of the chapters in part 4 of this book, we use the SSI Scorecard we developed in chapter 4. For each of the five categories in the Scorecard (Bottom Line, Business Efficiencies, User Experience & Convenience, Relationship Management, and Regulatory Compliance), the chapter author(s) evaluate whether the impact of SSI is Transformative, Positive, Neutral, or Negative.

For this chapter, we use the story of Jackie leasing an apartment. We evaluated that SSI will be Transformative for User Experience & Convenience and Regulatory Compliance. It will also have clear positive effects for the Bottom Line, Business Efficiencies, and Relationship Management categories (table 18.1).

Table 18.1 SSI Scorecard: apartment leasing

Reference

1. Zuboff, Shoshana, 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs.

1. One of our explainer videos uses a Sparkly Ball (from our box of craft supplies) to represent the third-party identity provider: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=81GkdBRmsbE&feature=emb_logo.