SSI has become a major technology theme for governments ranging from the United States, Canada, Korea, and Australia to New Zealand. In the previous chapter, two of the leading SSI pioneers in Canada explained how the Canadian government is approaching SSI. In this chapter, legal expert Dr. Ignacio Alamillo-Domingo shares the evolution of digital identity in the European Union to explain how all paths in Europe lead to SSI. Dr. Alamillo-Domingo is a legal expert in the European Blockchain Services Infrastructure project who is involved in standardization activities at ISO/TC307, CEN-CLC/JTC19, and ETSI TC ESI. He has a PhD in public law about the eIDAS.

Creating trust in internet transactions is one of the primary requirements for the proper functioning of the Information Society and—from the European Union (EU) perspective—of the internal European market. As chapter 1 explained, the initial internet architecture designed in the 1960s and 1970s did not prioritize security. Achieving an environment in which people feel safe and confident is necessary to promote the adoption of digital identity.

EU Regulation No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and the Council of July 23, 2014 on Electronic Identification, Authentication, and Trust Services (eIDAS) for the internal market was an important and transformative milestone in the legal regulation of the assurances of juridical traffic performed electronically [1].

Note In the EU, primary legislation is approved in a joint process involving the European Parliament (formed by representatives elected by European citizens) and the Council of the EU (formed by the Prime Ministries of the Member States of the Union). They are frequently referred to as co-legislators.

The eIDAS regulation constitutes the main trust framework in the EU and the Euro-pean Economic Area (EEA) to support the juridical acts (expressions of will, intended to have legal consequences) performed electronically by natural and legal persons, typically on the internet. It is the historical result of two different approaches to identity management: public key infrastructure (PKI) and, later, federated identity management (FIM).

Note You can read more about trust frameworks, also called governance frameworks, in chapter 11. We discuss PKI in chapter 6 and decentralized identifiers (DIDs) in chapter 8.

Before we can jump to how Europe is working toward SSI, we need to provide some background on how PKI and FIM evolved in Europe. This will allow us to understand the benefits of SSI in a European context.

24.1 PKI: The first regulated identity service facility in the EU

From a strictly chronological point of view, European legislation initially regulated information security mechanisms and services that were considered useful for conducting legal transactions on the internet. These included digital signatures: data appended to, or a cryptographic transformation of, a data unit that allows the recipient of the data unit to prove the source and integrity of the data unit and protect against forgery, e.g., by the recipient (ISO 7498-2).

Digital signature techniques ensure data origin authentication and data integrity and are used in non-repudiation services:

-

Data origin authentication is corroboration that the source of data received is as claimed (ISO 7498-2).

-

Data integrity is the property that data has not been altered or destroyed in an unauthorized manner (ISO/IEC 9797-1).

-

A non-repudiation service generates, collects, maintains, makes available, and verifies evidence concerning a claimed event or action to resolve disputes about the occurrence or non-occurrence of the event or action (ISO/IEC 13888-1).

Thus, digital signatures were considered a potential substitute for handwritten signatures, especially when based on a PKI.

PKIs are formed by certification authorities (CA) that issue digital certificates binding a public key with an identified entity. They offer important levels of assurance (LOAs) concerning a person’s identity or a system holding a public key. Thanks to the mathematical properties of the asymmetric cryptography underlying digital signatures (explained in chapter 6), digital certificates support the attribution of a signed document or message to a person identified in the certificate. In this sense, a digital certificate constitutes an identity service that can potentially be offered by private sector companies.

Nation-states realized that enacting laws for digital signatures based on CA activities could be an essential element for developing e-commerce. Another perceived benefit—and goal—was the possibility of harmonizing new laws for digital signatures within the United Nations framework—or at least establishing common principles in this field and providing an international infrastructure.

24.2 The EU legal framework

In the EU PKI, certificates are electronic documents issued by authorized entities that bind the name of a natural or legal person (and any other relevant identity attribute) to that person’s public key. By following strict practices and controls, a certificate enables any party receiving a digital signature to have a high level of confidence in the signatory’s identity.

Public key certificates are regulated as a specific trust service by the eIDAS Regulation. The regulation differentiates between three types of certificates according to their use: natural person certificates are used in connection with electronic signatures, legal person certificates are used in connection with electronic seals, and website certificates are used in connection with browsers and web servers.

The three types of certificates regulated in the EU legislation correspond to three uses of asymmetric (public key) cryptography:

-

A digital signature created by a natural person is called an electronic signature, which can have the same legal effect as a handwritten signature.

-

A digital signature created by a legal person, called an electronic seal, can have the same legal effect of ensuring the integrity of the data and correctness of the origin of the data to which the electronic seal is linked.

-

A digital signature is used as an authentication method implemented by a server (e.g., using TLS 1.2). This is the kind of signature verified by your browser when you navigate to a website and see a green lock in the address bar.

In the eIDAS Regulation, the digital certificate is always treated as an electronic proof of identity, whether for a natural person or a legal entity and regardless of whether the certificate is used to support an electronic signature, an electronic seal, or the authentication of a website.

To underpin the confidence of relying parties, the eIDAS Regulation establishes a set of minimum standards for the content of each type of certificate and the minimum obligations of providers issuing them. These standards apply to all trust service providers (TSPs; in the EU, people or legal entities providing and preserving digital certificates to create and validate electronic signatures and to authenticate signatories as well as websites).

This raises the question of whether these certificates can be used in an entity-authentication service. Some Member States have admitted qualified certificates as a means of electronic ID at the national level. If a Member State decides to permit the use of electronic signature certificates or electronic seal certificates as an identification system for cross-border purposes, then this system will be part of the EU’s Federation Identity Management scheme, explained later in this chapter.

Why should eIDAS-compliant PKI be considered an important first step toward SSI in the EU? There are several arguments for this:

-

PKI legislation embodied in the eIDAS Regulation created a legal statute concerning the subscriber of a public key certificate. That means a TSP issuing a qualified certificate is subject to the strict rules of the eIDAS Regulation (and any national law complementing it), including the legal conditions for issuance and revocation of certificates. Because TSPs may only revoke a certificate when a legally recognized reason occurs, there is greater assurance in the certificate owner’s autonomy. This at least partially aligns the EU PKI system with SSI principles.

-

The eIDAS Regulation also defined the legal requirements for advanced electronic signatures and advanced electronic seals. These include ensuring that the signatory has control of the signature- or seal-creation data, thus ensuring personal autonomy in managing their data so third parties cannot seize it. In the case of natural persons, this control must be exclusive, which again is very aligned with the core assumptions of the SSI philosophy.

-

The eIDAS Regulation also regulates the possibility of delegated user key generation and management with the delegating user maintaining control. This aligns with another important SSI principle supporting custodial cloud wallets and digital guardianship, as explained in chapters 9, 10, and 11.

-

Practices, procedures, and legal knowledge developed for PKIs may serve as a baseline for SSI, specifically for the verifiable credential (VC) management lifecycle. This enables the SSI infrastructure to take advantage of more than 20 years of international standardization at organizations such as the ITU Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T), the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI).

While PKI is a valuable first step toward establishing a global identity metasystem for the internet, it cannot cover all the needs of such a system, even at the regional level. And PKI falls short on some SSI principles. For example, users are still dependent on a single TSP that could delete their identities for legitimate purposes, even if their activity is legally regulated and this deletion must respond to a reasonable cause. PKI also does not support segregating identifiers from other identity data.

Finally, PKI does not support selective disclosure: a data subject’s ability to control disclosing only the exact data required by a verifier. Current digital certificate technology forces the user to share all the information contained within the certificate (which may infringe on EU data-protection regulations such as GDPR).

Due to this limitation, a certificate can contain only the minimum set of data required to support electronic signatures, electronic seals, and website authentication. Thus, paradoxically, in some European Member States, a certificate does not contain enough information to be used for unique identification purposes, at least at a European level.

These issues—and the fact that Member States and private businesses provide other authentication mechanisms such as strong multifactor authentication—have prevented PKI from becoming a global identity metasystem. The one exception may be TLS server certificates that comply with CA/Browser Forum policy requirements. The major internet browsers enforce these by including (or excluding) in the trust stores the root certificates for recognized CAs. There is a real danger that this practice could affect millions of users’ certificates and identities if a CA is abruptly revoked due to a breach or industry pressure.

Note Organized in 2005, the CA/Browser Forum (https://cabforum.org) is a voluntary group of CAs, vendors of internet browser software, and suppliers of other applications that use X.509 v.3 digital certificates for SSL/TLS and code signing.

This danger has helped drive interest in the SSI concept of a decentralized PKI (DPKI). This concept, first explained in chapter 1 and explored in more detail in chapters 5, 8, and 10, is a way of delivering the same core benefits that PKI supports today without the need to rely on centralized service providers (such as CAs) that are single points of failure. The attraction of DPKI meant a second step toward the identity metasystem occurred in the EU between 2000 and 2014: the construction of an EU identity federation and the further expansion of PKI.

24.3 The EU identity federation

Due to the identity-proofing limitations of the EU PKI regulations, and because the national electronic identification schemes of each Member State are not recognized by the other Member States, the EU created the eIDAS Regulation. It is an EU-wide identity federation that provides a mutual recognition system for any eID. In essence, it functions as a regional identity metasystem, although with some limitations.

24.3.1 The legal concept of electronic identification (eID)

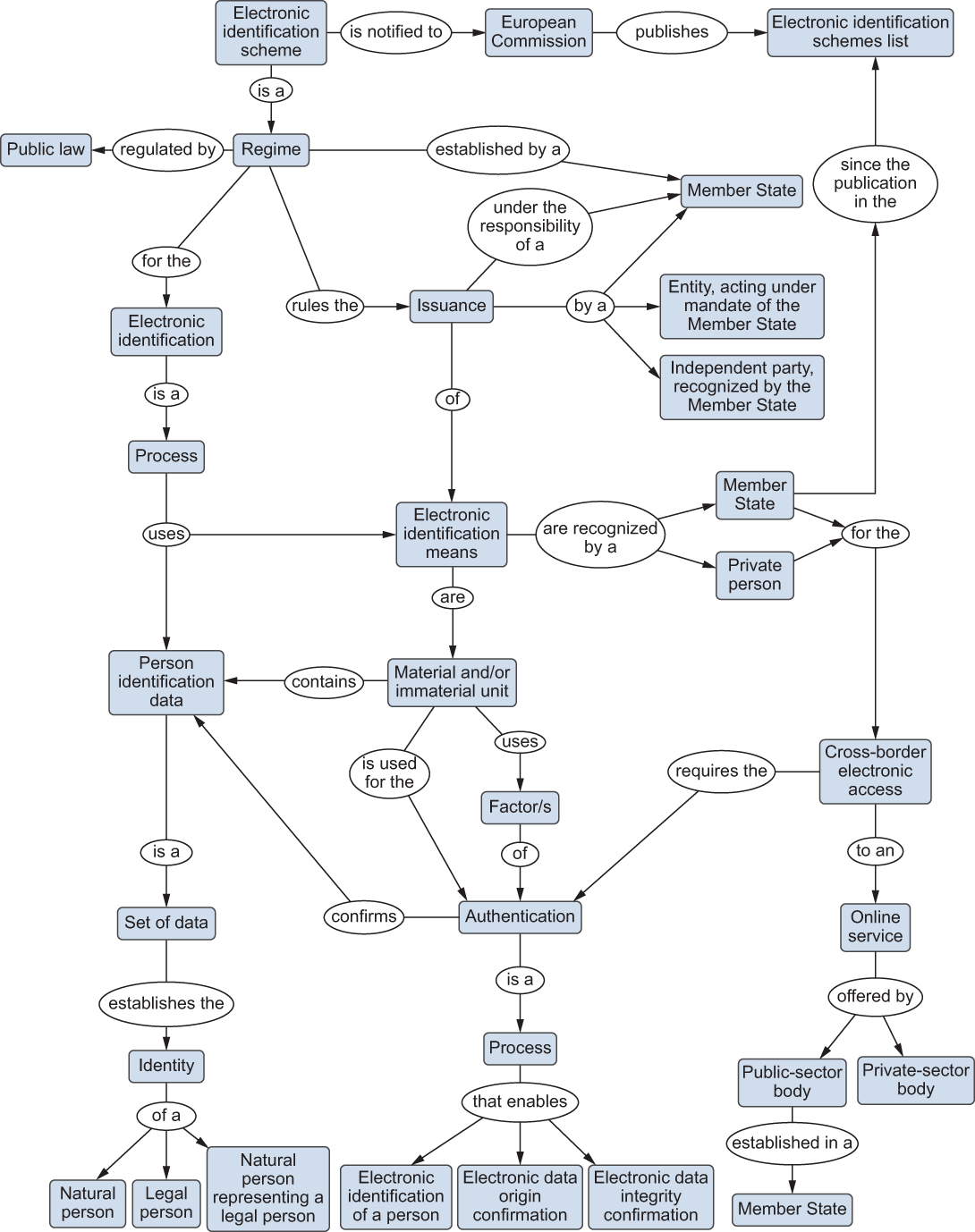

To function as an identity metasystem, the eIDAS Regulation defined a specific vocabulary for comparing and evaluating national identity schemes and federating them at the EU level. Figure 24.1 illustrates the following concepts [2]:

-

Electronic identification —The process of using person identification data in an electronic form uniquely representing either a natural or legal person, or a natural person representing a legal person (Article 3(1) of the eIDAS Regulation).

-

Person identification data —A set of data enabling the identification of a natural or legal person, or a natural person representing a legal person, to be established (Article 3(3) of the eIDAS Regulation). Such a digital identity can be a name (one or two surnames) and a registration number assigned by the government. Given the existence of various sets of data that identify a person and the legal challenge of creating a unique identification aggregated with all possible identification data, the regulation generally refers to partial electronic identities. In the case of the eIDAS, there is a minimum data set required to access public services.

Figure 24.1 A conceptual map of electronic identification in the EU

-

Electronic identification scheme —A system for electronic identification under which electronic identification means are issued to natural or legal persons, or natural persons representing legal persons (Article 3(4) of the eIDAS Regulation).

-

Electronic identification means —A material and/or immaterial unit containing person identification data used for authentication for an online service (Article 3(2) of the eIDAS Regulation).

-

Authentication —An electronic process that enables the electronic identification of a natural or legal person, or the origin and integrity of data in an electronic form to be confirmed (Article 3(5) of the eIDAS Regulation), referring to three well-known security services.

From an EU legal perspective, the concept of electronic identification is characterized by issuing units that contain identification data that serve for cross-border authentication, at least for public services. This legal abstraction supports many potential technology implementations, including digital certificates embedded in computer applications or on cryptographic cards, physical or logical devices that generate unique authentication codes (such as single-use passwords), and many others.

The sheer number and diversity of these different means of electronic identification—many of which were already being used in various Member States—created real security and interoperability challenges that hindered or prevented cross-border operations. This is why an EU-wide identity metasystem was needed and why pure entity authentication in cross-border transactions was the new regulation’s core innovation. In addition, the eSign Directive covered authentication of data origin as well as data integrity—both of which are standard properties of advanced and qualified electronic signatures (and now also of advanced and qualified electronic seals).

This EU identity metasystem can support the core concepts of SSI because it is sufficiently neutral from a technological and organizational perspective.

24.3.2 The scope of the eIDAS FIM Regulation and its relationship with national law

As stipulated in Article 1(a), the eIDAS Regulation is limited to establishing “the conditions under which Member States recognize electronic identification means of natural and legal persons falling under a notified electronic identification scheme of another Member State.” This means the core of the identity trust framework deals with the security and interoperability of electronic identification systems.

Note From the perspective of the eIDAS Regulation, we can see that electronic identification is a collection of electronic public services, unlike trusted services—which can be offered as public or commercial services—that may be provided under direct or indirect management techniques. Electronic identification could also be a private service recognized by the Member State (see Article 7(a) of the eIDAS Regulation), always under its liability according to Article 11 of the eIDAS Regulation.

According to Article 6(1) of the eIDAS Regulation, for cross-border recognition of an electronic identification system to have a juridical effect, it must satisfy all three of the following conditions:

-

The electronic means of identification must have been issued under an electronic identification scheme included in a list published by the Commission in accordance with Article 9 of the eIDAS Regulation (which requires a Member State to provide advance notification of a new listing).

-

The electronic means of identification must use a substantial or high security level, and this must be equal to or higher than the level of security required for public sector bodies to access that service online in the first Member State.

-

The public sector body must use a substantial or high level of security in relation to accessing that service online. (Surprisingly, this provision precludes the possibility that a person with a better system than that requested by the public sector body can use it. For example, this will happen with a Spanish citizen who intends to use a Spanish National electronic ID to access a service in another Member State that only requires a low-quality password, due to the low-security sensitivity of the service.)

By establishing these requirements, the eIDAS Regulation focuses on enabling legally valid mutual recognition of digital identities issued by Member States within the territorial scope of application of the regulation, extending the right to use such systems to the rest of the EU Member States.

Although the legal effect of eIDAS is guaranteed only in relations between individuals and public sector bodies (in keeping with the EU’s policies to enable the use of electronic means for public administration of Member States), EU FIM is designed to allow the use of electronic identification means notified by Member States under eIDAS for private sector purposes if so authorized by the identity provider’s Member State.

There are several reasons eIDAS FIM may be considered a second critical step toward SSI adoption in the EU, especially in legally regulated environments:

-

The eIDAS Regulation is the primary electronic identification trust framework in the European Economic Area.

-

An eID is a building block of the Digital Single Market, allowing the establishment of cross-border electronic relationships in the e-Government field.

-

eIDAS may be extended to include the recognition of eIDs for private sector uses, such as Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT), online platforms, etc.

-

The technology-neutral approach could easily allow the usage of SSI systems, constituting a real opportunity for their adoption.

-

The eIDAS Regulation has a strong influence in the international regulatory space, thanks to the contributions of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).

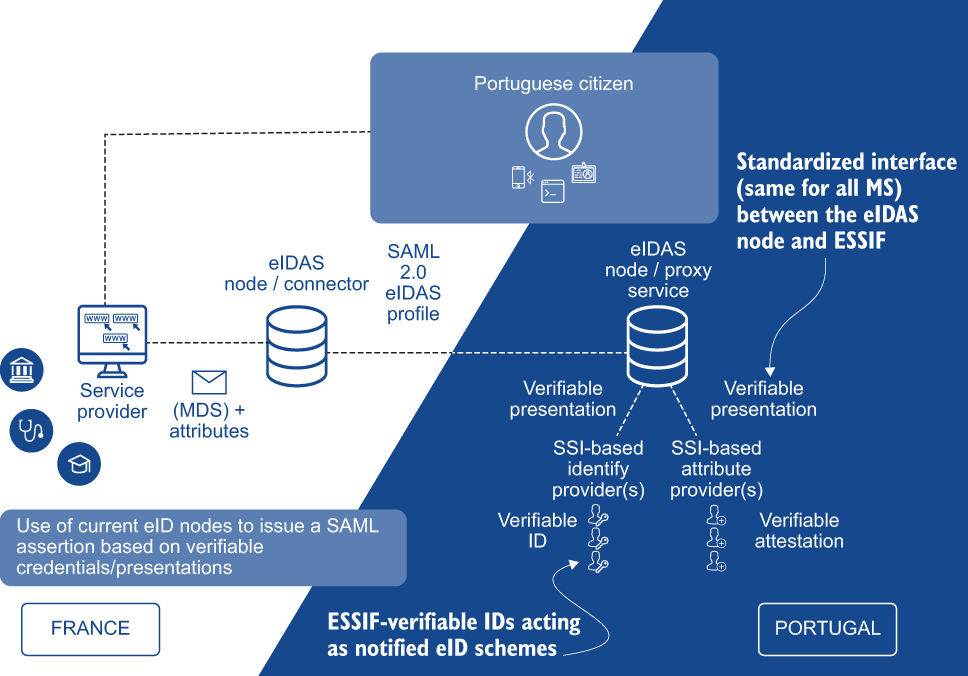

Figure 24.2 The eIDAS proxy node-to-proxy node scheme

At the time of publication, the EU identity metasystem has some potential limitations, especially in the proxy-to-proxy model shown in figure 24.2, which is more widely adopted than the proxy-to-middleware model.

The intervention of proxy nodes introduces some potential issues that can be better solved by adopting the SSI paradigm:

-

Social and legal issues —The SSI model of distributed authentication can overcome the perceived lack of privacy with the centralized authentication required in the proxy-to-proxy model—an issue that could hold back the adoption of eIDAS. It will also allow the sharing of very sensitive data under conditions that will be acceptable from the EU GDPR perspective.

-

Technological and infrastructure capabilities of the identity provider (resilience, continuity, capacity, security, and so on)—The SSI model will allow substituting a distributed ledger technology (DLT) for the centralized authentication node in the proxy-to-proxy model, which can both eliminate a single point of failure and offer better security guarantees.

-

Financial and liability aspects —The public single-node model used in the proxy-to-proxy scheme makes it difficult to transfer costs to the trusting entities and overloads the issuer’s liability, especially if it is a public authority. In contrast, with an SSI model using a DLT, the relying parties can bear the cost of authentication without the need to establish complex legal relationships. This approach can also reduce the potential liability of the issuer.

24.4 Summarizing the value of eIDAS for SSI adoption

As introduced in the previous sections, the eIDAS Regulation must be seen as the result of historical evolution, embodying two different identity trust frameworks:

-

A PKI-based trust framework for qualified certificates that confirm the identity of a natural person, legal person, or website. Qualified certificates are usually used for identifying a person at the national level.

-

A FIM-based trust framework covering any technology used for cross-border electronic identification and authentication purposes, including qualified certificates that comply with the minimum data set and security requirements.

The eIDAS Regulation may offer excellent support for legally valid SSI verifiable credentials. This is one reason Tim Bouma, co-author of chapter 23, coined the expression legally enabled self-sovereign identity (LESS identity) [3]. This term identifies a specific category of SSI VCs that meet legal requirements to differentiate from other SSI solutions that use different social trust mechanisms, such as reputation.

Legally valid SSI VCs would enjoy all of the advantages discussed in this book, such as full user control and portability, minimum disclosure, strong security and privacy, and broad interoperability. Given all of these advantages, how should eIDAS evolve in the future? Should it be adapted to include specific support for SSI?

This subject was addressed in a 2020 document called the SSI eIDAS Legal Report (https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document/2020-04/SSI_eIDAS_le gal_report_final_0.pdf). It makes the point that a technologically neutral, broad interpretation of the eIDAS Regulation (more specifically, of the certificate definition) would support the use of a specific DID method (chapter 8) plus a specific type of VC (chapter 7) as a qualified certificate for both natural and legal persons.

Because qualified certificates confirm the subject’s identity (signatory or seal creator), this specific combination of a DID method and a VC would have the same legal effect as for qualified certificates. It would also support advanced and qualified signatures and advanced qualified electronic seals in blockchain transactions. Moreover, this approach would facilitate a smooth transition from PKI to DPKI [4] and SSI systems while maintaining and even fostering a valuable market and reusing a convenient and proven supervisory and liability regime.

Although today electronic identification under the eIDAS Regulation is clearly aligned with classic FIM infrastructures such as those based on Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) or OpenID, nothing in the eIDAS or its implementing acts should prevent the use of an SSI system as an end-to-end means of electronic identification.

Thus, the SSI eIDAS legal report considered a VC used for identification purposes an eIDAS-compliant electronic means of identification that could at the very least be used for transactions with public sector bodies and public administrations and—if so decided by issuers in the framework of the notified electronic identification scheme—with private sector entities for AML/CFT and other uses.

24.5 Scenarios for the adoption of SSI in the EU identity metasystem

Two different scenarios would help the adoption of SSI in the European identity metasystem. The first scenario (figure 24.3) would maintain the proxy nodes approach, as the SSI system would be used behind the currently existing node, ensuring immediate recognition and interoperable operation. While this is a transitional scenario, it would enable SSI to be integrated quickly, and it would not require any legal modifications to the eIDAS Regulation. It would not solve all the issues previously identified, but it would allow the incorporation of valuable SSI use cases already proven in private sector transactions, bridging trust between these two worlds.

Figure 24.3 Adoption of SSI in the current EU identity metasystem

The second scenario (figure 24.4) would evolve a middleware model, substituting SSI operational protocols and artifacts for the eIDAS proxy nodes. This opens many more potential uses.

As explained in section 10.1 of the SSI eIDAS legal report, eIDAS does not cover identity management in a broader sense, only electronic identification. Thus, it is not immediately applicable to issuing and sharing other VCs or presentations (European Blockchain Services Infrastructure [EBSI] and European SSI Framework [eSSIF] verifiable attestations) such as diplomas and employment credentials. This is understandable due to the legal standing of such credentials for proving identity. However, it makes it difficult to use such credentials in cross-border scenarios because of multiple sectoral regulations.

Figure 24.4 An SSI-enabled EU identity metasystem

This second scenario could pave the way for the eIDAS Regulation to be extended to become a generalized framework for issuing and exchanging any type of VC. In other words, the real innovation SSI technology offers eIDAS is transforming the regulation to support legally valid, cross-border identity attestations of all kinds: age verification, diplomas, employment, and so on.

To be clear, the historical legal approach in the eIDAS Regulation is fully justified. It is concrete and detailed, containing precise legal definitions related to electronic identification (electronic identification scheme, electronic identification means, personal identification data), authentication, levels of assurance, interoperability, and governance rules. In short, it is a full legal trust framework for cross-border authentication, which is a vital part of identity management across a Union of Member States.

The proposal in this scenario would create a parallel trust framework for issuing and sharing other identity attributes. This objective cannot be accomplished in the same way as the current approach for electronic identification because the semantics and rules of these other identity attributes are quite different. While these other attributes could be used to identify a person (in a very general sense), they are not designed to be used for identification and authentication. However, the legal technique to support the juridical validity of these credentials would be the same; that is, the same notification procedure the eIDAS Regulation currently uses for registering new electronic means of identification would be used to register many other types of identity credentials as a way to ensure their quality, security, and interoperability.

The analysis of any sectoral framework regulating identity credentials (for example, diplomas in support of accreditation of professional qualifications, a use case included in the EBSI) shows the complexity of transforming the classical certifying documents normally issued by public administrations. To facilitate a quick transformation into verifiable attestations, a new equivalence rule could be proposed. This rule could authorize the use of a verifiable attestation according to the (new) eIDAS Regulation whenever a legal norm required a document certifying an identity attribute for a natural or a legal person.

24.6 SSI Scorecard for the EBSI

The European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI) is a network of distributed nodes across Europe that will deliver cross-border public services as a result of the European Blockchain Partnership: a declaration signed by 27 Member States, Liechtenstein, and Norway to cooperate in the delivery of cross-border digital public services with the highest standards of security and privacy.

Europe, by building on its existing eIDAS infrastructure for electronic identification of individuals and legal entities, is well equipped to become a world leader in SSI adoption. This is fitting with Europe’s democratic traditions and a significant opportunity to make Europe an example for the world.

The benefit evaluation of widespread SSI adoption for the EU is color-coded as follows:

For this scenario, we consider the impact to bottom line and regulatory compliance to be positive. All other categories are evaluated as transformative (table 24.1).

Table 24.1 SSI Scorecard: European Blockchain Services Infrastructure

References

1. De Miguel-Asensio, P.A. 2015. Derecho privado de Internet (Quinta ed.). Cizur Menor, Navarra, España: Aranzadi.

2. Alamillo Domingo, I. 2019. Identificación, firma y otras pruebas electrónicas. La regulación jurídico-administrativa de la acreditación de las transacciones electrónicas. Cizur Menor, Navarra: Aranzadi.

3. Bouma, Tim. 2018. “Less Identity.” https://trbouma.medium.com/less-identity-65f65d87f56b.

4. Reed, D., and G. Slepak. 2015. “DPKI’s Answer to the Web’s Trust Problems.” White paper. Rebooting the Web of Trust.