4 Working on Location

Safety

You can shoot in the safety of your neighborhood, you can shoot on soundstages or at production offices, but the moment you step outside and into the world, the parameters always change. One of the greatest things about action sports is their ability to creatively overcome obstacles in the real world by turning architecture and other man-made objects into the ultimate playground. The downside is twofold. First, this ability often winds up taking the athletes into more-dangerous parts of the city to session that perfect rail or hit up an amazing ledge. The second problem is that most high-end buildings — such as banks and museums, which often have incredible architecture — are open during the day, leaving nights and weekends as ideal times to session them. If you’re traveling around a city at night or even on a Saturday in a less-than-appealing part of town, keep a real close eye on your gear. Although most athletes don’t invite crime and are often very street-smart themselves, you still may be carrying anywhere from $3,000 to $10,000 in equipment with you, which is rather inviting.

In 2000, a photographer and good friend named Chris Mitchell was road-tripping through Las Vegas, shooting stills of a group of skaters alongside a videographer. After shooting all day, they returned to their small hotel just off the Strip to rest and make evening plans. Someone must have been watching them during the day and then followed them back — because moments after Chris and the videographer had settled into their room to download that day’s shots, the door burst open and several armed and masked men entered. With guns pointed, these guys took most of the video- and still-camera gear and left. This is a rare thing to happen in any industry, but the bottom line is that it did — and could again. In a case like this, there may be little that could have been done to prevent the robbery; however, there are still things to be learned. Perhaps simple things, such as staying in larger hotels with security or utilizing more-discreet backpacks for gear. Either way, you can do only so much to protect yourself.

My advice is simple: when you hit the road, don’t take all of your gear. If you think you may end up in questionable areas, pack light and bring only what you are likely to need. Nothing says “mess with me” like a brand-new HD camera with heaps of accessories and bags everywhere. As mentioned above, I always try to use low-key, subtle backpacks (see Figure 4-1). Earth tones, preferably black, are a great way to not advertise “camera inside” to a passersby.

Figure 4-1 A perfect camera bag for on the road: the Ty Video 2 by Ogio.

Figure 4-2 A fully customizable interior.

Airline Travel

When you hit the road with your gear, you may also encounter the potentially dangerous scenario of checking luggage, cameras, and tapes on airlines. My experience over the years has been that traveling with expensive gear is not a problem, so long as you have insurance. If you are flying into a location the day of a shoot and would have no time to rent or buy new gear, then carry your camera on the plane in a soft carry bag (see Figure 4-1) that will fit in the carry-on storage bin. If you must check it, don’t check a soft bag. Instead, rent or purchase a hard case, such as a customizable Pelican Case, that can be locked and safely stowed in the plane’s cargo hold as checked baggage. Online stores such as B&H Photo Video in New York City and Fry’s Electronics will carry large Pelicans. The interiors of these cases are full of small removable foam blocks that you can tear out to make the perfect tight-fitting camera and accessory slots. The risk for checked luggage is that even cases can be stolen. I had a complete Sony three-chip camera package stolen once off the baggage-claim carousel at LAX coming home from a shoot, so be careful. Your only options to avoid being in the hole during travel are to carry insurance for your gear, get a production insurance policy for your shoot, or have a renter’s insurance policy that covers gear when you’re away.

If you’re traveling home with tapes, then you may be concerned about the X-ray machines affecting your shot footage. In the old days, you could just ask for a hand check, but since 9-11, most airports will require that all material go through the machine. Sony and other companies have conducted extensive testing over the years with all types of DV, SD, HDV, and HD tapes, and found that no standard X-ray airport check-in machine will affect the magnetic tape. With FAA-enforced tightened airport security, there are now out-of-sight explosive-detection systems that incorporate far more powerful X-ray scanning for checked luggage. These systems are known to fog undeveloped, unexposed film. Although they’re said not to affect magnetic tapes, I always prefer to carry mine versus checking them. If you do have undeveloped, exposed film, you can also consider separating your tapes and shipping them back using various trackable overnight shipments (more than one in case a shipment were to get lost). Just call and verify with the shipping company, though, because most overnight services use aircraft — they, too, may have X-ray scanning devices.

Cops and Security Guards: How to Deal with Them

There’s one constant in the world of action sports, and that’s the recurring issue with authority figures. The concern is justifiable when you consider that many great street spots are public areas that create liability issues. When bikes, skateboards, in-line skates, or other devices grind on rails and ledges that weren’t meant to be used that way, damage does happen.

Some cops and security guards will simply ask you to leave the premises on the grounds that your sport isn’t allowed. Others will tell you, especially in the United States, that liability is too big an issue, so you’ll have to go. And finally, on rare occasions, you’ll meet security officers who will be very cool about it and look the other way. I remember shooting a skate video in Europe once where I realized that the American obsession with liability is just that: an American obsession. We were sessioning a ledge down a set of stairs when a security guard came around the corner to talk to us. Instantly, half of the athletes I was with started to walk away; the other half of us stood our ground, basically cornered by the guard. He walked right up to us, and we figured he was about to kick us out. Instead, the guard said that he’d be in a booth right around the corner should anyone get hurt or need anything. We stood silent, confused by the response. Apparently, there are countries in which people support the popular activities of their youth, and the adults don’t sue one another for their kids’ accidents. Accidents happen — that’s life.

Unfortunately, you’ll be hard pressed to find a security guard like that in the United States, so you’re going to need to take on a new approach in any U.S. shooting locations. Believe it or not, I actually know skaters who used to get kicked out of skate spots — and they’re now grown up, married, and work as security guards. The bottom line is this: there are some cops and security guards who are actually cool and are even fans of action sports. So when someone they might otherwise respect comes at them with attitude and disrespect, of course they’re going to kick that person out. After thousands of experiences and years and years of shooting and skating urban spots, I’ve found that a lot of the time, if you stop and hear out the guards, then talk to them with respect, they’re more likely either to be cool about letting you stay, or at least take off and essentially give you free range at your next skate spot.

Rolling with the Punches

Studios are highly controlled environments. From the sets to the lighting to even the weather, you almost always know what you’re getting. It’s on location that things can — and often will — change so frequently that your shooting needs to be as creative as the athletes themselves. When you’re filming out on the streets, you can’t always control what will happen next, which can be part of the adventure. From that last-minute thunderstorm to the crazy guy on the park bench who offers up words of wisdom to your talent, it’s paramount that you always be ready to go. When I’m shooting documentary style, I keep the camera in my hand, turned on, and with my finger just a flick away from that red button. It’s crucial to be ready to roll if something starts to happen. Sometimes you don’t know how someone will react at first, and you may even want to start shooting subtly. Then, afterward, ask for their permission to use what you’ve recorded. Some great advice I was once given is that sometimes it’s easier to ask forgiveness than permission.

Illustration 4-1 Busted by security.

Another big variable is the weather. I try to check the forecast and either bring a rain cover for my camera or improvise with a plastic shopping bag. Even the slightest bit of moisture will wreak havoc with the electronics, so keep your gear dry. If you’ve ever shot in extreme cold, then you also know this can shut your camera down. They may not be flesh and bone, but cameras will get glitchy and eventually seize up if they get too cold. PortaBrace (see Figure 4-3) makes cold-weather gear that actually has internal compartments for hand-warmer packets (like ones you’d use on a ski mountain). If you’re shooting in the snow, or even just on a cold night, you’ll need the warmth. I shot nights once in Prague in the winter, while making a documentary on the Vin Diesel film xXx, and my Sony DSR-PD170 was tough, but nothing could take that cold. Despite wearing two heavy jackets and wrapping the camera tight in a PortaBrace Polar Mitten, the cold was still piercing.

Figure 4-3 Polar Mitten cold-weather case by PortaBrace.

Photo by Jasin Boland.

If you don’t have the money to buy cold-weather gear, then a great makeshift option involves two plastic bags, some hand warmers, and, of course, duct tape. Start by inserting a few warming packets inside the first bag and taping each packet to the sides of the bag. Be sure not to cover the packets in tape, or the heat won’t radiate. Next, put the second bag in the first one so it lines the insides, then tape them together. This will put the heater packets between the two bags, and create a warm layer of insulation (just like the wall of a house). This will also prevent your camera and hands from being exposed to the direct contact of the heaters, which can cause burns. Now cut a hole in the bottom of the bags just large enough for your lens to fit through. Tape the bag to the end of your lens to make sure that it won’t move or get in the shot. This is also a seal to help keep the warmth in and the cold out. Finally, pull the bag over and down, covering the camera and leaving access to the controls through the back, via the main opening in the bag. If it’s incredibly cold out, you can even double-layer the outer wall of the bag and then seal up the main opening around your wrist; but remember that you’ll likely want to be able to get your second hand in and out regularly for accessing most of your manual settings. The end result may not look like much, but it should keep your gear functioning and your exposed hand from getting frostbite.

Protecting Yourself

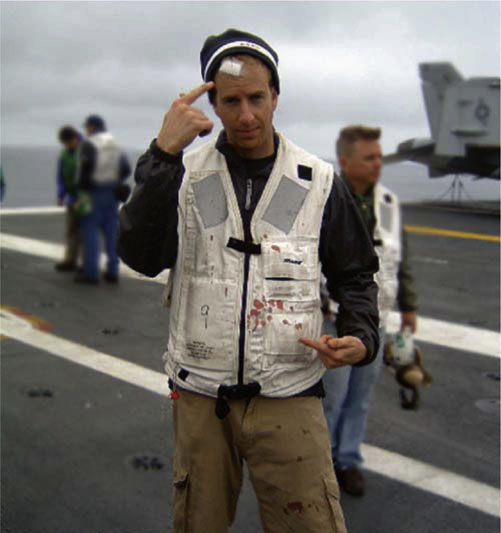

There are plenty of things to jump out and ruin your day while shooting on location. All too often, we focus solely on the normal dangers at hand: protecting the camera, watching the ground you’re shooting from, and so on. What gets left behind are the not-so-standard dangers, the typical things that you take for granted every day because your attention is distracted by your shoot. In this case, I’m referring to such common mistakes as walking into the tail stabilizer of an F-14 Tomcat.

Figure 4-4 Aircraft carrier USS Nimitz.

In 2005, I was shooting somewhere off the coast of Mexico on the flight deck of the nuclear aircraft carrier the USS Nimitz. It was near the end of a two-year journey for a documentary I was making called Harnessing Speed, for director Rob Cohen’s film Stealth. We were shooting night two, around 3 a.m., and no one had slept the first day because of the noise of fighter jets catching trip wires and being catapulted off. The film crew set up an incredibly visual rain scene with massive pipes and hoses on the carrier deck surrounding the fighter jets. The lighting and view of the moonlit Pacific Ocean were incredible, so I decided to drop the Sony HDR-FX1 HDV camera I was shooting with and go grab the full-HD camera I had in my bunk belowdecks, a Sony HDC-750A. I hurried past several parked F-14s and onto the catwalk that surrounds the railingless flight deck, some 70 feet above the cold, black ocean. As I was returning, rushing to get the shot, I ran up the catwalk steps to the flight deck, watching my footing carefully — and not noticing that I was quickly approaching the rock-hard tail section just above me. With camera and gear in hand, and no helmet on, I walked headfirst up and into the tail stabilizer of an F-14 Tomcat.

Figure 4-5 The morning after my run-in with an F-14.

This was, of course, a random occurrence that happened in an anything but common environment. But the lesson learned is that no matter where you are, there are always going to be things that will jump out at you. No matter how comfortable you get, shooting anything can be dangerous. If you add to that a dangerous environment, the potential problems can compound very quickly.

Shooting with Other Cameramen

Many action-sports cinematographers and cameramen will tell you that their goal is always to get the best shot. Unfortunately, if you shoot at events where other operators are going to be, then you sometimes have to settle for working around and/or with them.

There are times, such as when you’re hired by the event company itself, that you may actually have priority over where you want to shoot. If this is the case, then you should be respectful of the person you might need to ask to move. Introduce yourself first and find out whom they’re shooting for, make sure you mention whom you’re working for, then ask them politely if they wouldn’t mind trading spots with you. If you get any resistance, you can either move on, try one more time to reemphasize how important it is to the event producers themselves, or, if necessary, simply tell them that you have to shoot from there. Just know that if you kick someone out of his or her spot, you may have lost an ally — and the action-sports industry is very, very small.

If you’re shooting an event as a general media person, meaning you have no direct affiliation to the event, then you have no right kicking anyone out of anywhere, so you’ll have to work with others. Oftentimes cameramen are looking mostly for particular athletes, not all of them, so if someone’s in a spot you really want to shoot from, ask them if you can jump in to just shoot your athletes, then hop out when their athletes are approaching or taking a run. If the cameramen are shooting everyone, then ask if they wouldn’t mind trading out a little; most operators are friendly because what goes around comes around.

Figure 4-6 A crowded deck of cameras.

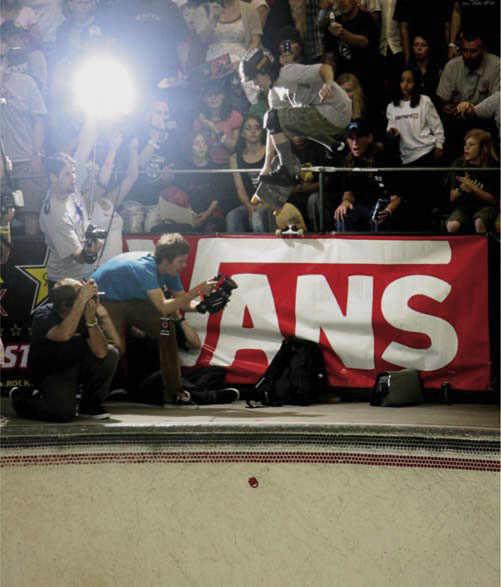

If you’re shooting on a ramp or street obstacle with a fish-eye, you’re going to need to get close to the action. Again, if you have seniority over others, you should still be conscientious about how much you’re getting in everyone’s shot. There is a rule of common etiquette among cameramen that allows them to all work together (like living under the same roof). Most will be okay with your grabbing some fish-eye lens shots, but don’t take advantage of it; get a few shots, then get out. Everyone wants some clean shots of athletes with no cameramen in front of their lens.

If you are on the deck of a ramp, shooting wide with others who are also wide, now comes a little tricky maneuvering. Let’s say an athlete is grinding across the coping of the ramp from your right to left, but to your right is another cameraman. You can step farther out onto the coping than he is, and shoot around him (with the camera basically hanging out over the ramp) as the rider approaches you both. But now, as the athlete gets close, you are going to have to step back onto the deck as you pan left, allowing the rider to pass you, but also allowing the other cameraman to match what you were doing, but on your right side. This technique is an often-unspoken switch that will happen on ramps and street courses. It’ll allow both of you to get relatively clean shots of the tricks without seeing each other. It does, however, take a little practice, and it’s always crucial that you never risk getting in the athlete’s way, or distracting them, just so you can get a shot.

Figure 4-7 Working the deck to get the shot: Vans Pro-Tec Pool Party.

The Politics of the Industry

Skating and other action sports weren’t always political; compared to other businesses and professional sports, they still aren’t very political today. But when you’re working with professional athletes, dealing with sponsors, and shooting large-scale events, it’s hard to avoid at least some politics.

Most politics come from the increase of money in the industry. Athletes have an obligation to their sponsors to promote them, and you may be a conduit for doing that. When you’re shooting interviews with athletes, consider that what they’re doing for you is a favor, by taking time out of their day, just as you’re doing them a favor by helping to promote. It’s a two-way street, and you can go a step further by incorporating their sponsors in your shot. Also be mindful of your shot’s background, on the chance that certain event banners may conflict with the sponsor that the athlete rides for. If this is the case, try framing up nonconflicting banners as a means to help out the athlete and the event sponsors who are also helping you.

If you decide to shoot a major competition such as the X Games, you’re going to need to contact them well in advance and get a media pass. You may have seen event badges or bracelets on all participants, authorized media, and crew. Although pretty much all action sports will allow you to shoot home video from the stands where spectators sit, you’re not likely to get the best angles or coverage from there. Before a big event will give you a media credential, they’ll want to know whom you are shooting with and what for. Some televised competitions don’t like their events showing up in skate videos, but they’re okay with news and general publicity, so this may be a somewhat gray area that you’ll have to research and work with or around.

Figure 4-8 Various event media credentials.

So from the politics of shooting with other cameramen to working with the event producers to gain access, when you enter the professional world of action sports, there’s some navigating to be done. But don’t let it discourage you. At the end of the day, almost all athletes still ride because they love it, and this core value winds up being the point of the sword for competitions and shoots. Some action-sports athletes may have mainstream sponsors (American Express and Toyota, for example), but even these sponsors understand that their riders represent them only on the unspoken grounds that they can continue doing their sport freely and in their own way. When you turn pro in football and other conventional team sports, you enter a world of rules and often-uptight expectations presented by the Establishment. The relaxed form of self-expression that made action sports so popular in their infancy still reigns today — and hopefully, will always stay at the core of action sports.