11 Big-Set Production: An Overview

So you shoot action sports, or perhaps you used to shoot action sports, but now you’re looking to move on or into something newer, possibly bigger. Many filmmakers continue into other aspects of production as they go. It’s a huge industry, and there are countless outlets to get involved in. Whether you want to try stretching your legs by working on a large feature-film set, or you are going to make your own feature film with an action-sports theme, this chapter will give you a broad understanding of big-set production, and a few ways to break into it.

From the first silent black-and-white films to the cutting-edge 3-D technology poised to change the industry, the movie process on set has remained one of the few unchanged elements throughout the years. Film sets can provide the ultimate learning environment for you. Don’t just look at your time on set as learning about how to make movies — also look at it as a means to learn professional techniques and tricks that you can then take home and implement in your smaller projects. Everything you learn will be an enormous asset to your action-sports productions, so do your best to take it all in.

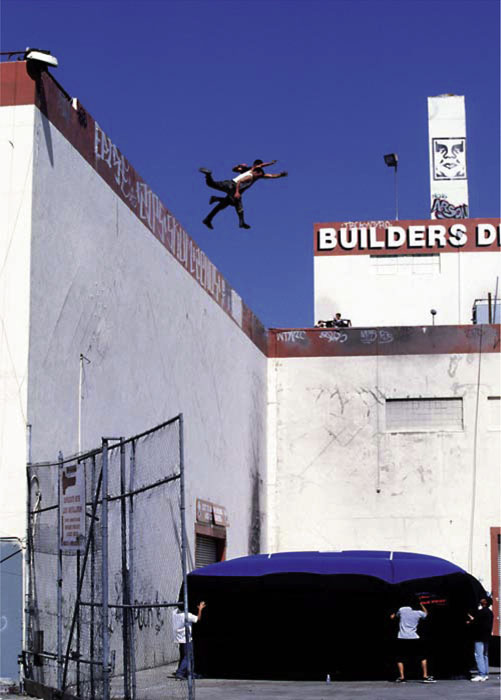

Film sets can range drastically in shapes and sizes. Even studio film shoots can include anywhere from a couple dozen to a few hundred people on set. Take the case of the summer action film xXx from Revolution Studios. There were days in which the cast and crew totaled only 40, but other times as many as several hundred. This is because scenes themselves vary so greatly in complexity. For example, large crews are needed for a huge scene with explosions, loads of extras, enormous lighting setups, and massive sets — but then not for a small conversation on a beach between two people.

Figure 11-1 A large film set.

If you’ve ever been on a large movie set, then chances are you know how hectic it can seem — various departments all moving in different directions as if it were total chaos. Yet somehow everyone seems to know exactly what to do and when to do it. It can really be quite impressive to watch.

My first experience on a movie set was for Batman & Robin, with George Clooney and Arnold Schwarzenegger. We were shooting at Warner Bros. on their largest soundstage. My first day there, I saw a hundred people all moving about, and I couldn’t understand what they could possibly be doing. As I wandered inside, the outer walls of the set were unfinished two-by-fours, sheets of plywood, pipes, and so on. It didn’t look impressive. Then I stepped through a doorway and into a room so large and incredible it suddenly all made sense: an enormous re-created museum that had massive columns, a huge lighting rig suspended from the ceiling, and a hardworking crew polishing every last detail of the set to create an immense reality the way only movies can. All of the crew members that I saw were working for key departments, each of which had a specific number of personnel working to achieve their specific goal. Table 11-1 shows a breakdown of a typical film’s crew and department list.

Table 11-1 Key departments on a big summer-movie production

| • Production assistants (PAs) | Entry-level position, typically assist the ADs |

| • Armory | Handle weapons such as guns and blank ammo |

| • Art department | Production and set designers |

| • Camera department | Operators, focus pullers, film loaders, etc. |

| • Casting | Responsible for finding and casting talent |

| • Catering | Meals |

| • Construction | Building/executing set construction |

| • Director and assistant directors | Usually a 1st AD and a 2nd AD work for director |

| • Grip | Lighting and rigging technicians (e.g., dolly grip) |

| • Greens | Trees, shrubs, grass, flowers, etc. |

| • Lighting and electric | Electricians and a gaffer set up lights |

| • Locations | Scouting, finding, locking filming locations |

| • Props | Finding, making, and providing all on-set props |

| • Makeup/hair | Talent hair and/or makeup stylists |

| • Script supervisor/continuity | Tracks each shot with the script for continuity |

| • Set decorating | Dresses the film set |

| • Sound | Booming and mixing all sound on set |

| • Special-effects department | Handles all on-set effects such as smoke and fire |

| • Stunt department | 2nd unit director, stunt coordinators, and stuntmen |

| • Technical advisers | Unique subject experts used for guidance on set |

| • Transportation | Cars and trucks for cast, crew, and equipment |

| • Visual-effects department | Supervise shoot to better incorporate VFX later |

| • Wardrobe | All costumes for talent |

If you want to get involved but you don’t know anyone, stuntmen can sometimes be the easiest to get to know, especially if you’re an athlete. Most stuntmen come from unique backgrounds such as martial arts, car racing, or even action sports. They operate as a tight group, working with their peers and watching out for each other’s safety.

Feature films may seem overwhelming if you’re new to them, but like the stunt team, each department operates on its own as a small, unique team of experts in that category. They will interact closely only with other departments that directly relate to what they’re doing. For example, the camera department is led by the cinematographer, and thus they interact with lighting and grip, but rarely does a cameraman need to speak with makeup or locations. In addition, the lower you are on the totem pole of that department, the more isolated and focused your work may be. A camera or film loader — who is responsible for making sure that all film magazines are loaded, organized, and ready to go — may spend very little time at all on set if he’s busy loading and dropping new film magazines off to the ACs (assistant cameramen). In fact, a film loader’s interaction may be limited just to the ACs.

If you have shot action sports and are trying to get involved in movie production, or perhaps there’s a film on snowboarding shooting near your hometown, then you may be able to get involved and learn more by applying to be a PA (production assistant) or personal assistant. Oftentimes crews will travel with only their key personnel, and then hire locals to help with the more basic tasks on location. If a movie is coming to your town, either contact your local city hall or look up the movie on the IMDB1 and see if the production company is listed, then send them a résumé and email asking how to get involved.

As a personal assistant, you might be responsible for getting the director coffee, or working with a producer on and off set to make sure they can do their job in your town. PAs usually get a little bit more on-set action, but that job has a wide range of duties as well. Some people have amazing PA experiences — working with cast, ADs (assistant directors), or just helping on set. Others have less-exciting experiences — helping to stop traffic all day from a corner nowhere near the set. A unique way into the business is as a writer. By this route, you can spend all your time at home, possibly never even on or even near a set. Scripts now have festivals as well (see Withoutabox.com for a partial list), so it’s easier to get discovered as a first-time writer. Then, as a successful writer, you can slowly make the transition to directing, if that’s your goal.

This is what makes the film business so exciting. Every production and every day of every production is different. You never know what you’re going to get, so by jumping in feet first with enthusiasm and motivation, you set yourself up to learn, make connections, and begin to climb the ladder in Hollywood.

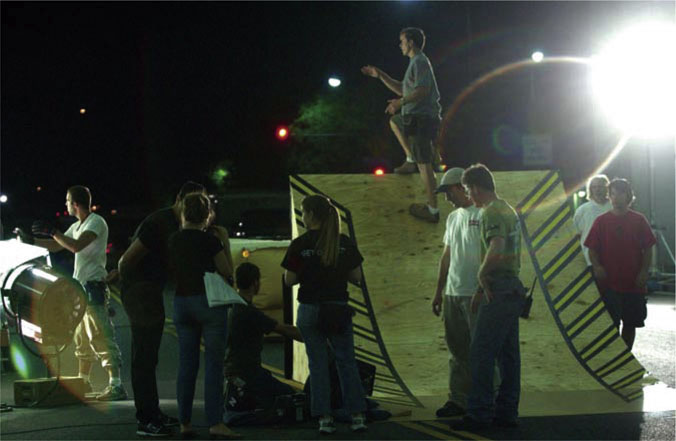

Figure 11-2 On the set of director Bill Kiely’s Vans commercial with Bucky Lasek.

So you’ve decided to make your first large project. Perhaps you’ve got a rich uncle, or maybe you’ve written a script on action sports and you’re going to raise the money. However you’ve gotten your financing, here are some key steps to consider as you move forward. First off, you aren’t the first to make an independent film, so the best place to start is with those who have come before you. We always hear about the self-financed small films that make it big: Napoleon Dynamite, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, and The Blair Witch Project, to name a few. But what we never hear about are the countless productions that never make it to the screen — or, worse yet, to the edit bay. There are heaps of online independent-filmmaking web sites that offer forums, bulletins, and articles on the successful and unsuccessful paths of those who have walked before you. From indieWIRE.com to FilmTies.com, you’ll find countless sites devoted to independent filmmaking. The key is to do your homework to best ensure the success of your project.

The second thing to remember is that most action-sports videos sell to enthusiasts of their respective sport. If you plan on making a feature film with action sports, and hope that mainstream audiences will enjoy it, then you’ll need a mainstream story. Nobody goes to see Happy Gilmore with Adam Sandler because they love golf. The film’s positives — a good story, good actors, and fulfilling character arcs — are enough. This holds true for many films, but unfortunately, most action-sports narrative films that have come before us have all focused heavily on the “extreme” sports aspect of their movie instead of the story. So if you plan to make a feature film, without or even with action sports involved, make sure you keep your story and characters as the focus.

Your next big goal will be to start preproduction. This will include building your crew and making the creative decisions that will shape the world you’re going to shoot. Large-scale productions are put together by a producer and a line producer. If this is your creative project, then you should be focusing on directing. Don’t worry about the daunting task of building your crew; instead, find someone you trust to handle that aspect. If you don’t know where to begin, go online and find an experienced producer who can build your crew for you. That is their job, and on a large project, you shouldn’t be worrying about that aspect anyway. Producers are responsible for hiring most of the key crew, and for working closely with the line producer to find crew and manage the budget of the movie. Together, these two positions are the basis for getting everything to the set that’s needed. It’s then up to you, working with your crew, to assemble the pieces into your vision.

Figure 11-3 Shooting pro skateboarder Danny Way, downtown Los Angeles.

Set Etiquette

The director may be the point of the sword on any movie set, but it is always up to you to act professionally and properly while on set. Set etiquette will vary greatly depending on what position of the crew or cast you are filling. Here are a few simple tricks and techniques to maintaining proper set etiquette.

If you’re visiting a set for the first time, remember this: things move fast and inconsistently. If you’ve ever visited an assembly shop or machine room, you’ve seen the precision repetition of the process. So-and-so picks up such and such, moves it here, gets another, repeats. On movie sets, everything is always changing, and no one has any one repeatable path — so keep your eyes open. From carrying light stands to moving set cars, you can find yourself very quickly in the way of the flow. No one on a crew knows when they’ll be in the way either, so it’s nothing to worry over if it happens once or twice, but don’t get so immersed in a conversation or camera you brought that you fail to notice the three guys pushing a crane your way. You’ll hear expressions such as “Hot points coming through!” — which simply means that something sharp or pointed (say, a tripod) is headed right at you.

You’ll also notice that most crew members tend to either be on the move working, or just sitting around. This is where the expression “hurry up and wait” comes from. On the set of movies, you aren’t always needed — but when you are, you need to be ready. So the idea is that you can sit there and chat all day long if there’s nothing to be done — but when you hear your name or department called, you move immediately. You’ll notice that most crew members have earpieces for their walkie-talkies as well. This can make for an interesting first experience when you’re talking to someone, and they suddenly look away and walk off. It’s understood in production that when you are called, you go. If everyone finished up the conversation before going back to work, films would never get made.

Another key approach to being on set is to keep your back against something solid. A good choice would be a wall. If you stand out of the way against a wall (one that isn’t in the shot, of course), then you’ll more than likely be in the safest place possible. Out-of-the-way corners are great spots to quietly observe and get the feel for the set. As mentioned, every day and every set is different, so even if the filmmakers are having a great time one moment, things could be going wrong the next — and you never want to be the one in the line of fire.

I spent six months living in Australia in the winter of 2004, working on the production of Stealth. We shot a great deal on soundstages, then moved into the Blue Mountains outside Sydney. On an unusually windy day, we were shooting in a deep valley near a stream. Everything was going fine, and the production seemed calm and typical of any other day — when a giant gust of wind came barreling down the valley wall. We had a large white cloth reflector tied off in a metal frame on stands. The reflector was restrained for safety atop a large rock. But Mother Nature has a way of letting you know who’s in charge. With next to no warning, that reflector said hasta la vista to the sandbags as it started to take flight. Like any respectable crew member, the nearest grip grabbed hold to secure the reflector — only to take off with it. Not possessing the aeronautical design of even a Wright brothers’ test, the reflector pretty much went earthbound and took that brave grip with it. A couple feet of water from the stream broke his fall, and he came up soaked and okay, with eight lives remaining. This was a huge crew well versed in production, and even then, random things like this can happen. The lesson here was twofold: keep your eyes wide open and your feet on the ground.

Figure 11-4 Stage 5, Fox Studios Australia, outside Sydney.

Finally, if you’ve been hired to work on the set and you’re a bit unfamiliar with procedures, consider the following summary of basic principles that apply on most new jobs and are key on film sets. First, show up on set early. Make sure you’re there before your actual call time. From finding crew parking to waiting for a transport van to drive you to the set, you’ll just make a better impression and be more relaxed if you get there early. Next, most crew members are friendly and outgoing, so be polite; say hello; and, most importantly, introduce yourself and find out what they do. If you’re not good at remembering names, then come up with a trick that works for you. Crews can be large, and you may run into and/or be working with these people, so get to know them by name. Third, you’ll want to be motivated and focused but also humble. Nobody likes a know-it-all, and you’re part of a team now, so focus on your job and your department. Keep your ears open for someone to call out your name or those of fellow department members. Lastly, don’t be afraid to ask questions. If you don’t know something, ask. Most crews are happy to share and explain how something works. Just try not to ask anyone who’s in the middle of working. The members of your own department are best for questions because you don’t want to disturb or bother the wrong person by accident (such as the director).

Networking

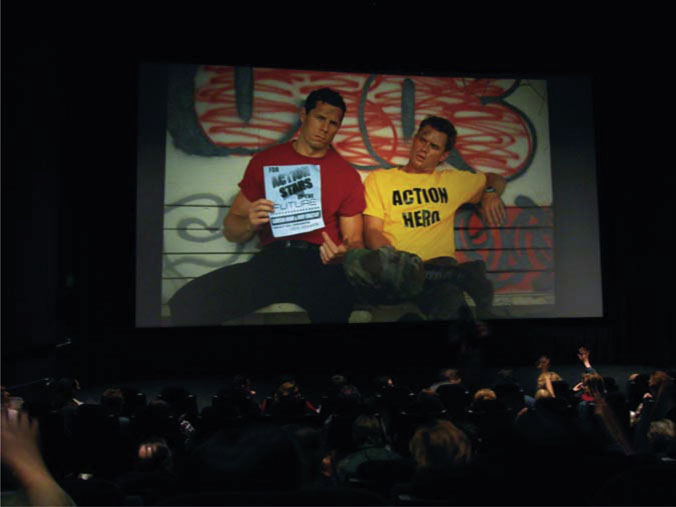

So you’re on set working with a big crew, and now you want to network. One of the best ways to get future jobs in the film business is to be referred by someone in the business. Many cameramen will work their entire lives for the same DP (director of photography) once they get in. They may start as a film loader, then climb to a second AC, then first AC (or focus puller), than eventually an operator or even DP. A good friend and longtime industry cameraman, Richard Merryman, has shot more than 25 movies. He got his start as a film loader. In 1981, Richard met Oscar-winning cinematographer Dean Semler and went on to work for Dean on all his movies. I first met Richard and Dean in 2001 during preproduction on xXx. At the same time, I met a talented young producer, Amy Wilkes, who was on set with her husband, Rich, who had written xXx. After becoming friends, Amy produced a short film for me, which Richard shot, called Men of Action (see Figure 11-5). Dean offered enormous help by arranging our cameras for us. Our friendship began on set, which is how you’ll meet many of the people that you might spend your career working with on various projects.

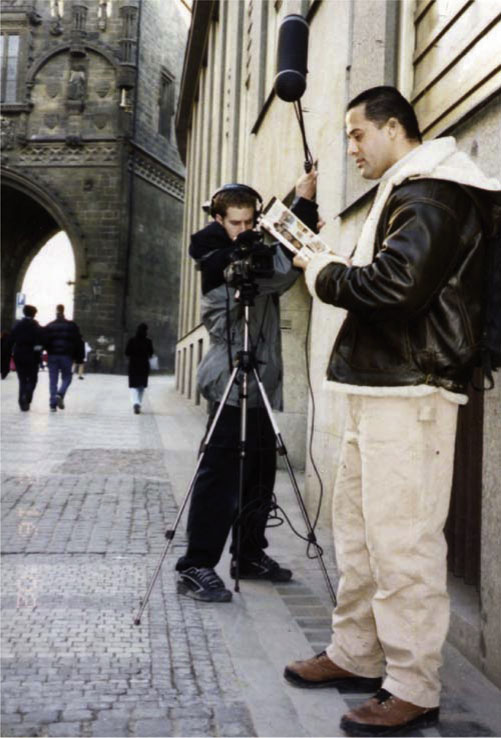

Figure 11-5 On the set of Men of Action with Richard Merryman.

Photo by Chris Mitchell.

If you’re on a movie for any great length of time, you should make friends naturally. However, if you’re on for only a week or two, and you want to network and try to make some new connections in the industry, then here are a few tips. First, you should pick a department to network with that is of true interest to you. If you want to be a cameraman, then meet the loaders, talk to them, and see if they’ll introduce you to the cameramen or DP. It’s crucial, though, that you don’t disturb the director — or anyone else, for that matter — while they’re working. A good time to introduce yourself or say hello is in the morning, when everyone is just settling in. Usually by the end of the day, the director and others are rushing out to screen dailies — or they have meetings, and the film is still on their minds. You’ll find during shooting that there are occasional breaks, and if you watch the director or others closely, you can observe when they are working (which includes thinking), and when they are not. If they appear to be out of work mode, and you can catch them for a moment, then a polite introduction and hello is usually fine. You can even express your level of interest and motivation to learn more. Many great filmmakers got started by volunteering themselves or interning to learn the ropes. There may not be any money in it, but the wealth of knowledge and relationships can be invaluable. While I was in college, my first real gig was interning nights at a company called T-Bone Films in Santa Monica. Doing tape-to-tape edits for filmmaker Evan Stone and producer Craig Caryl was a great stepping-stone to the world of production.

Another option to network and meet new crew members can be the wrap party for any one project. If you’ve been working especially hard and have been very punctual, then chances are you’ve made numerous overworked crew members’ lives a little easier. When you approach them, be polite, as always. Ask them this: if you ever have any questions, could you stay in touch? You can let them know you would like to work with them again. Request that they call you if they ever need help on anything. Chances are, if you shone on set, you’ll get a call.

Shooting Behind the Scenes

Well, it’s officially standard on just about every film now. And one of the easiest ways to get feature-film-set experience that you can use on your action-sports projects is by shooting behind the scenes. The “making of” has become a staple of movie sets, and the opportunities for action-sports cameramen and documentarians to get onto big sets are expanding. In the years before DVD extras, there would be only a set photographer shooting stills for publicity, and an occasional EPK (electronic press kit) crew getting bits for television promotion or archival purposes. Today, Hollywood films will spend upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars on creating and documenting the process. This comes in large part because of the added value (literally) of DVDs. As home-video technology continues to expand (see , Distribution), the ability to create more and more extra content will grow, as will consumer expectations.

From interactive-menu design and featurettes to online viral campaigns and commentaries, behind-the-scenes work on films has never been growing as quickly as it is right now. Top content creators still exist as large companies, but countless small film productions hire independent videographers to shoot their projects. By getting involved with a larger company, or trying to get on several small films to get the ball rolling, you can carve out a niche for yourself while observing and learning the craft of feature filmmaking.

Figure 11-6 On set and behind the scenes.

All of the previously discussed rules of set etiquette still apply, but when you’re on set shooting behind the scenes, you’ll spend much more time floating around between departments than you will sitting still. A typical “making of” or EPK position will begin with your speaking to the producers of the movie and working out what you’ll be doing and what the budget will be for it.

For smaller-budgeted independent features, there are two main jobs you can go after. The first job is that of just shooting the behind-the-scenes footage. Oftentimes the production company or studio behind the film will just want you to shoot, then hand over the tapes — they will handle editorial themselves. If this is the case, then you’ll need to get a feel for what their schedule is like and how many days you’ll be needed. You can start by asking them what their expectations are: did they hope you’d be on set every day, or are they planning on just having you out for a few days? If they’re unsure, then consider the size of the budget and whether everyone is getting paid well on this shoot, or if it’s a project on a really tight budget. If it’s the latter, then you’ll have to decide if you’d rather spend more days on set and get paid less, or work fewer days but make more. To find out the budget and how tight it is, you could ask a friend who might be working on the project, or you could be very open about it with the company or studio (or whoever is hiring you) and just come right out and ask. If you do decide to ask, explain to them that their answer will help you create a schedule and budget that will more likely work for them.

Your next step will be to sit down and develop a proposal. If you know the shoot is 28 days, and it’s almost all dialogue in the same room, then you may not need to be on set every day. On the other hand, if the film travels all over the state, and almost every production day contains interesting material, then you may want to be there as many days as possible.

You’ll definitely want to be there on all of the key days. These include days that feature big action, days when all the cast is on set, days with important plot points, and so on. You can ask for a current shooting schedule (called a one-line schedule) and a copy of the script to help you lay this all out. If you pitch yourself for nearly every day, consider what your cost of operation will be with any of your gear, then simply tally it all up. Just remember, though, that if you come up with a high day rate for yourself, then add on your camera, a sound person, and even general expenses, it can get quite costly, fast.

A final consideration for making your proposal will be format. As always, you need to pick what you’ll shoot on. Although many big productions are interested only in HD (high definition) or HDV (high-definition video) nowadays, many small productions are less concerned and will settle for DV (digital video). Just keep in mind that you may have to rent gear to meet their format expectations, so this could affect your budget significantly.

Figure 11-7 The “making of”: director Rob Cohen walks with Jeffrey Kimball.

Photo by Jesse Kaplan.

If you’ve been hired to shoot on set and to deliver final elements, then you have a few options on how to approach the job. If the company hasn’t told you or doesn’t know what elements they want for the DVD or promotional use, then you will have to pitch them on some ideas of your own. Although some companies will ask for a ten-minute featurette on the making of their film and perhaps a few other extras (see Table 11-2), most companies aren’t sure, and thus will be open to your ideas. If this is the case, then you should take the script home to read and have a few good brainstorming sessions on what you could do for it. Remember to be realistic in your proposals, though, so you don’t wind up promising more than you can deliver.

Table 11-2 Popular DVD extras elements for feature films

| Popular elements | Approximate length |

| “Making of” featurette | 3–90 minutes (average piece: 15 minutes) |

| Director or cast commentary | Duration of movie |

| Outtakes or bloopers | 3–5 minutes (music driven) |

| Cast/crew bios | text (1–3 pages each) |

| Element-specific featurette | 5–20 minutes |

| Behind-the-music featurette | 3–10 minutes |

| Deleted scenes | 2–8 scenes |

Once you’ve read the script and thought about it, consider what’s unique to this project and which elements stand out. If there’s a horror element, then a featurette on doing all the special effects and makeup might be interesting. If there’s a strong action-sports element, then a piece on action sports and who’s involved would be great. Just think outside the box, and even consider web spots that you could make for them.

When you get the job and arrive on your first day of shooting, you’ll want to find the ADs first off and introduce yourself. Before you even consider shooting, it’s always wise to make sure that the key people know who you are. ADs are responsible for running the set, so if you’re supposed to be there, and they’re aware of you, then you’re good to go. If you can, try to introduce yourself to as many people as possible before you roll. Begin with the director, who, like many people on the set, may not want to be shot. It’s a common courtesy that will make your day go much more smoothly. Even find time to say hello to the actors and help make them feel comfortable with you. As everyone becomes more open to you and your camera, you will get better material.

Use many of the camera techniques discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. Begin wide and far out, then slowly work your way in as people become more comfortable with your shooting them. Also find a nice balance of time when you are shooting and time when you are not shooting. This will give the cast and crew a break from the camera. No one likes to be filmed all the time. The best way to handle this can sometimes be to take an “out of sight, out of mind approach.” When you’re not shooting, try to fade back into the shadows, or put down the camera and just give people a mental break. It’s not only about whether or not you’re filming. If you’re standing there holding the camera at your side while everyone works, just by seeing you, they may feel like they’re keeping their guard up. You’ll make everyone’s day if you make things fun, easy, and painless for them.

When you’re on set shooting, you may not want to cover every take. Some directors may do up to ten takes, and your video camera can also affect the actors’ comfort zone. So try keeping your distance on takes until you know they are cool with it — and even then, never stand in an actor’s eye line while the movie is filming. If it’s an important scene, cover the 10 different takes from numerous angles. Capture the director watching one, then film the actors, then get a wide master, and so on. If the scene isn’t that important, don’t feel that you have to shoot every take; you’ll just be kicking yourself later when you scan through hours of repeating footage. On the other hand, be careful not to miss that outtake on Take 32. If you do miss something, don’t worry. Shots can get missed; it’s the nature of the game.

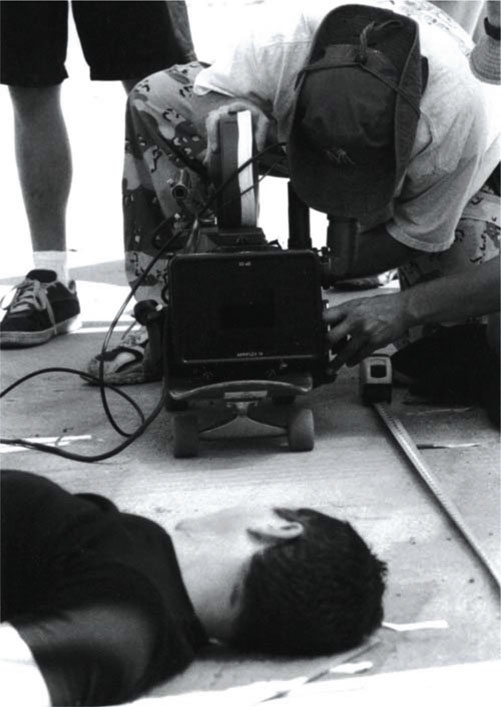

Some standard shots you can go for during takes include shooting over the director’s shoulder so you see the film set and his monitor (see Figure 11-8). Also try getting shots from behind the cameramen’s perspective, thus showing what they’re shooting (see Figure 11-9). In general, you want to stay out of people’s way both physically and mentally, while still getting in there to capture the best shots possible. It’s a delicate balance.

Figure 11-8 Over-the-shoulder shots.

Figure 11-9 Behind the cameraman on set.

Photo by Chris Mitchell.

How many tapes should you shoot? If you’re covering every day of a long production, and you have a good sense of what you want, need, and are capable of getting, then I find that one to two hours of tape is a good average. If you weren’t sure of any of the above, then I’d roll more to be on the safe side. If you’re there for only a few days of the entire shoot, then you’re going to want to get as much as possible. This doesn’t mean shoot the same take from the same angle repeatedly, but rather, get creative and see how different you can make everything look. If you’re the only one filming on set, then you should mix up your shooting style for possible other pieces down the road. Capture a take of a scene slowly, starting wide and zooming in patiently, then do another take with a completely opposite approach. This time, make the camera moves frenetic; crash-zoom in and land on a Dutched angle of the actor. The goal is to create options in post. Shooting these days can result in five to ten tapes. When you wrap on your assignment, if you’re just delivering tapes, find out if they want them at the end of the shoot or the end of every day; with the latter, you won’t have the responsibility of holding them for a month. When I created the xXx “making of,” I was overnighting boxes of shot tapes back to LA from the Czech Republic every few weeks.

If you’re doing post as well, you may need to dive right into it. Once you know what elements have been approved, you’ll want to start logging your footage as soon as you can. Behind-the-scenes shooting can result in lots of footage, so quickly getting a handle on it will help you achieve your edits. Expect to turn in rough cuts to the production company for approval, and make sure you have a prenegotiated number of allowed changes. Otherwise you could wind up doing far more work in post than you had ever planned.

Behind-the-scenes shooting is a great way to take what you already know about action-sports or documentary shooting, and parlay it into some on-set experience. This can really be perfect for establishing that knowledge base and for making connections in the world of feature filmmaking.

Commercials, Music Videos, and Short Films

If you plan to shoot something locally for a friend, an online competition, or even just for yourself, start by trying to put a good production team together from everyone you know. If you have friends who are ready and willing to help out, even if they don’t know the process themselves, get them involved and teach them what you know. Making films and videos can be a very fun but difficult task, so usually the more help you can get, the better.

Figure 11-10 Documenting the Men of Action “making of.”

Photo by Chris Mitchell.

Commercial production is a changing world. As mentioned in , advertisers are beginning to shift their money from television to the Internet. No longer is the industry locked up and unreachable. In the past, companies would go only with advertising agencies and large commercial production houses. However, with the changing front of advertising, more and more webisodes and web commercials are being done on the cheap, and thus below the radar of these agencies. This opens doors for you and other content producers out there.

Local companies can now afford to promote their products more easily, thanks to online video. If you want to get your foot in the commercial door, then start with a few specs. A spec commercial is essentially a spot that you make on your own for a company that is in no way supporting you. Popular spec-commercial subjects have included beers, cars, and foods. In 2003, DP Bridger Nielson shot a KFC spec commercial with me for our reels (see Figure 11-11).

Figure 11-11 KFC spec commercial shoot with DP Bridger Nielson.

Although it is possible to sometimes contact an advertising agency and see if they have any unused or old storyboards for commercial spots, you can simply write your own spec. Come up with a unique concept that promotes the product and works around your existing assets. If you shoot Freestyle BMX primarily, then consider making a spec commercial for a Freestyle BMX industry product, or you might simply incorporate Freestyle BMX into your commercial for another product.

Essentially, spec commercials can be the best way to build a reel that you can then submit to local retailers, production companies, or even agencies. It can be hard or almost impossible to get going in any industry without prior experience. By making a few specs, you’ll have the chance to show people your talent.

Other small projects that can allow you to stretch your creative legs include music videos. Pretty much anywhere in the country, you can find up-and-coming bands that would love to have a music video made. If you are interested in trying new projects and further honing your skills, then music videos can be a great way to do it.

Because of their nature, music videos are very often not linear stories. They may lack continuity and represent visual works of art. This allows for the widest range of creative expression, and can be far more forgiving when it comes time to edit. If your video is going to be a montage of the band’s performance mixed in with images of an athlete cruising down a long, windy hill, then you can shoot it all without worries of what shot will go where. Although some videos can be completely scripted, many are simply conceptually designed and outlined, and then final decisions are made in post. This tactic will give you the greatest creative range. If you’re shooting on a tight budget, you can be a little more carefree in your approach, less concerned for perfect lighting and continuity.

The subject of my first music video was a band called Slugg-O. A young director Sheldon Candis and I just set the band up in an alley in downtown Los Angeles. The band and their song were punk rock, so we decided that gritty and real would be our angle. We placed lights right in the shots and let them flare the lenses — it was great. Even hip-hop videos can be done with a fish-eye lens and a few creative locations. You should start by looking at what production equipment you have access to, then find a band that suits your taste. Post an ad online in your area on message boards for production and music (possibly on craigslist or MySpace). Once you start getting responses, talk to the bands about their expectations and your own, make sure you are both on the same page, and then begin to pitch ideas and concepts that you know you can make.

The key to a great video is your level of passion. Don’t shoot a video for a song you don’t like or can’t relate to. Music videos reach out to people and often invoke an emotional response from the music and images, so make sure the song is powerful to you emotionally, and that you have a clear vision on how to portray that emotion with your camera.

Figure 11-12 On set in the Combi Bowl, Vans Skatepark.

Courtesy Windowseat Pictures.

Commercials and music videos may allow you to disregard continuity, but when you’re ready to practice your storytelling narrative abilities, the short film is a great place to turn. Most popular shorts have ranged anywhere from 1 to 20 minutes. It’s tough to say what the ideal short-film length is. With user-generated content, television channels such as Current TV and web sites such as YouTube are now very popular. Many people love to tune in for 1- to 3-minute pieces.

If you plan to make a short, first you’ll need a script. This can come from you or any of your friends. You can even go online to find sites for short scripts and search the entire planet for a good one. Next, you’ll want to start filling in your cast and crew. In the past, I’ve shot various shorts that had as little as 1 cast member and 1 crew (see Figure 11-13), or as many as 60 people involved (see Figure 11-14). The deciding factor is really the content that you’re shooting, and how “big” or “small” you want the production to be.

Figure 11-13 Short-film shoot with F. Valentino Morales, no crew.

Figure 11-14 Men of Action short-film shoot, large cast and crew.

The key to picking a crew size comes down to numerous factors. An important one includes the decision to shoot with or without permits. If you’re going to get permits, as required by most state laws, they’ll cost you some money and take time and paperwork. It can be as simple as calling your local parks and recreation department, if that’s where you want to shoot, and asking what they’ll require. If you decide to guerrilla your shoot, then just remember you’re taking a chance, and any city official or owner of a private location has the right to ask you to leave. There are countless situations where you may never be bothered, including shooting with a very small crew, but I’d still advise finding out if you need permits and location releases for your shoot. Another factor for determining crew size can be how much time you want to spend shooting. If you have only an afternoon, contrary to the idea that more people can do more things, a big crew can actually slow you down. Being agile and mobile can save loads of time on set. As a director, you’ll essentially have less to choose from when shooting, which makes things go faster. There are times when a well-thought-out, simple concept, can make for a great two-day weekend shoot. These are good “practice” shoots, chances to hone your skills. When you decide to go for broke and invest your money in a big short, then a bigger crew with more equipment and cast may be appropriate. Just use your best judgment on when that time is right.

Think of shorts, music videos, and even commercials all as ways to expand your filmmaking toolbox. There are constant crossover skills to the action-sports projects you will do, and in that world, you can use all of the tricks and techniques you learn. Some projects will be bigger, some smaller — but they’re all still made with the same basic tools, beginning with you.