12 The Future of Action-Sports Filmmaking

One of America’s truly famous artist and avant-garde1 filmmakers, Andy Warhol, once said, “It’s the movies that have really been running things in America ever since they were invented. They show you what to do, how to do it, when to do it, how to feel about it, and how to look how you feel about it.”

There’s a certain irony here, in that countless artists and filmmakers of today were themselves influenced and shaped by Andy’s work. The truth is that media in totality provide a unique way for the world to communicate and know what others are up to. The visual arts of video, film, and digital media are a language, just like English or Japanese, and it’s through this language that filmmakers share ideas and information with the world.

As an action-sports filmmaker, just like any other type of moviemaker, you are participating in these conversations by sharing your ideas and visions. Perhaps you are showing what tricks athletes are doing in your area, how the athletes are dressing, talking, or even how they greet each other with the constantly evolving handshake that people do. Action-sports filmmaking models itself after the sports it documents. The genre is ever evolving, growing, and finding balance with the expectations of those who watch it — and of those who do it.

Figure 12-1 Filmmaker Chris Edmonds on location.

Photo by Tim Peare.

There are many places action-sports filmmaking can go. Some of these places are more likely than others, but inevitably, the ultimate destination is unknown. In the constant race to create new projects and original ideas, it is critical to consider what has come before, and where other types of media are headed. To predict the future of action sports, we must first consider where we began.

How Far Can a Progressive Sport Go?

In 1985, not one person had ever done a backflip in competition on a vert ramp. By the ’90s, skateboarders, Freestyle BMXers, and in-line skaters were all doing them. Then, by the early 2000s, as mentioned in Chapter 1, professional snowboarder and in-line skater Matt Lindenmuth did the first ever double backflip on vert. This was followed by FMX legend Travis Pastrana’s landing a double backflip on his dirt bike.

With current action-sports progression adding more rotations, bigger air, longer grinds, and mind-blowingly more-technical tricks, it’s almost safe to say that the sky is no longer the limit. Although all sports have experienced enormous highs and lows in popularity since they first hit the scene, the action-sports industry as a whole has continued to grow over time. Let’s consider skateboarding for a moment. In 1963, Larry Stevenson designed and sold the first professional skateboards (see Figure 12-2). At the time, skateboarding was just a “freestyle” activity, consisting of stylized turns and maneuvers. The following years were booming, and tens of millions of boards were sold. Then, out of nowhere, the industry collapsed in 1975, and skateboarding went underground. This put skaters back to the drawing board, which led to numerous tricks — including the Ollie — being invented. Although skateboarding slowly grew back into mainstream awareness, it died again — this time in 1991 with the U.S. recession. But by then, snowboarding was taking hold. This helped skateboarding grow back into public favor, along with in-line skating, which was at the time getting significant public attention. With action sports now growing in popularity, it was Tony Hawk’s 900 at the X Games in 1999 (see Chapter 1) that caused the world to go ballistic.

Figure 12-2 Larry Stevenson, skateboarding legend and inventor of the kick tail.

Action sports were here to stay.

Every action sport has had similar ups and downs throughout the industry’s relatively short life span, but it is worth noting the intense dues paid by snowboarding and skateboarding since their birth. This may account for their permanent fan base and place in the world today. The progressive nature of the sports will not change: new tricks will be invented, younger kids will someday outskate their idols, and new skate videos will find an audience.

If you plan to shoot another sport that is still going through growing pains, then consider the hills and valleys of the industries mentioned above, and how your action sport may be affected in the coming years.

A perfect example is in-line skating, which reached a low point in popularity in the early 2000s. Now that the sport is underground, in-line skating’s anti-cool status has slowly been getting new kids involved — in large part for the same reasons that kids first took to snowboarding, freestyle skiing, and skateboarding: these new pursuits went against what was popular and mainstream.

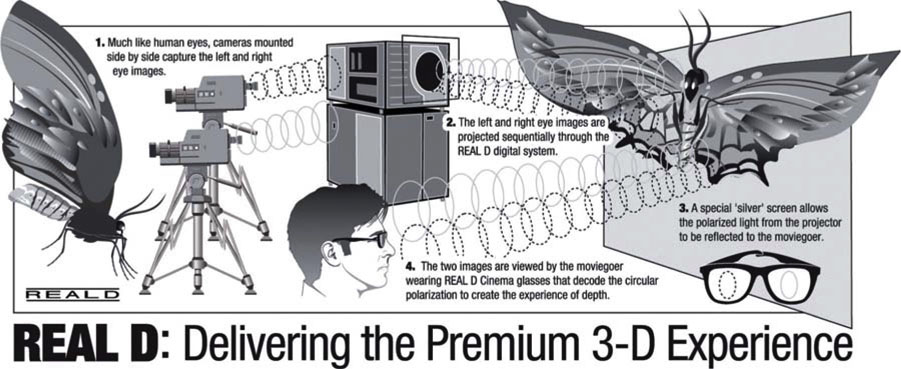

One would think that there must come a point in all sports when, no matter what level of popularity they enjoy, there simply isn’t anyplace left to go. The truth is that even when the well-established movie theater experience began to feel stale, back when surround sound felt like old news and Hollywood couldn’t squeeze any more explosions into 90 minutes, along came 3-D. There may not be 3-D action-sports films out there yet, but why not? How much more intense would a 900 on a vert ramp or a grind down a handrail look in 3-D? Or maybe consider what you could do using your computer and various effects programs. You might be able to take an action-sports video to a new, creative place. As the ideas become old, new ones will always surface. Just as tricks will always progress, there’s no reason the films shouldn’t progress as well.

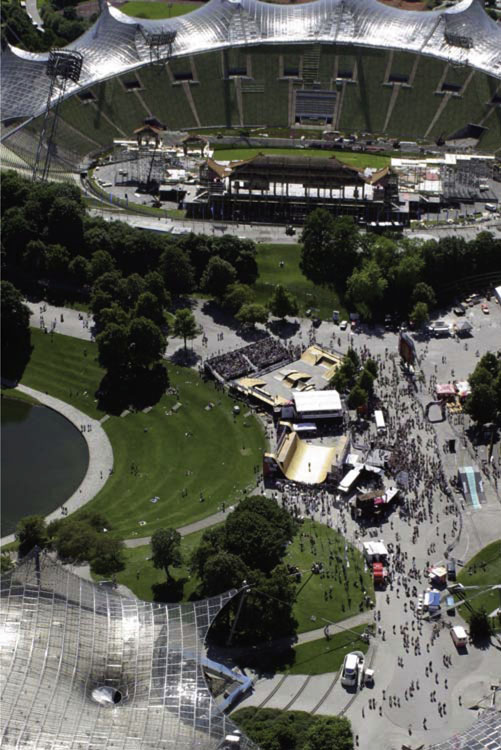

Figure 12-3 Action Sports World Tour, Munich, Germany.

Courtesy ASA Entertainment.

Technology and the Future of Filmmaking

He gave us The Terminator, Aliens, and Titanic. In 2009, James Cameron’s Battle Angel and Avatar mark the first in the wave of new digital 3-D technology to enter the big screen. The new polarized-glasses technology is far superior to the old blue and red glasses of the past. Theater chains continue to convert their projectors to digital systems that also handle 3-D, and the world awaits the spectacle and unique experience that new 3-D films will bring.

Yes, 3-D is the new frontier in taking theatrical experiences to the next level — and eventually home video as well. Even if you’re making action-sports projects, these technologies will affect you. It’s important to always keep an eye on the emerging technological front.

From his early days, even James Cameron has managed to keep one hand on technology, and the other on the heart of his projects: the stories. Jim Gianopulos, cochairman of Fox Filmed Entertainment, called James Cameron “not just a filmmaker,” adding that “every one of his films have pushed the envelope in its aesthetic and in its technology.”2

As this technology continues to expand and evolve around us, there will be countless new ways to embrace the production side of your projects, as well as the distribution. If 3-D cinema at the movies is a five-course meal, then that would make YouTube a PB and J — and most everyone loves both. Even two technologies from opposite ends of the spectrum still have enormous appeal to the same audience. In fact, when 3-D becomes a staple of big summer movies — just as HD has taken over from film cameras3 — then who is to say that it won’t trickle down in the coming years to the prosumer level.

Figure 12-4 Digital 3-D camera technology by REAL D.

In 2004, O’Reilly Media coined the phrase “Web 2.0,” referring to the changing face of the Internet. No longer is the web a place to stare at 2-D pages full of data. Instead, it has evolved into a place were users generate and share information. People post their bios, videos, stills, and ideas online; they react and respond to other postings, thus creating a snowball effect of shared content and creation. This network of sharing means that even the two-dimensional video projects of the past will evolve as online distribution evolves. Perhaps your future project will not only allow, but also depend on, user interaction.

Top action-sports videos such as 411VM video magazine already compile shots of tricks from numerous filmers all over the world. What if this were to happen automatically via a web site? Could a program be written to allow the top vote getters among user-posted clips to be automatically shuffled and placed into a video montage online? What if a program could even identify key “trick moments” as a way to sync each shot up to the recurring beats of the user-chosen song? These are just the beginning of the questions you need to ask yourself as filmmaking moves into the future. Three-dimensional digital technology, the internet as a means of sha content, and the creativity that only you can provide — these are building blocks of tomorrow’s films and videos. What they’ll become when put together will shape the future of the industry.

You Read the Book … Now What?

Whether you’re new to filmmaking or you’ve been shooting your whole professional life, chances are you are reading this book because you’re serious about expanding your skills. More and more people are picking up cameras today than ever before. From home moviemakers to aspiring producers of action-sports videos, the number of participants is growing every year. This means that by keeping yourself ahead of the game — and creating projects that are unique, and possibly that even fill a void that hasn’t been filled before — you’ll be able to hold an edge against the competition.

Figure 12-5 Action sports online with GrindTV.com.

The first key to finding that success is motivation. You have to consider what it is that you truly want to accomplish — and you have to mean it. Earlier in the book, we looked at the idea that many people have great ideas, but very few people execute those ideas. This holds true in every facet of life. Each day, thousands, if not millions, of original film ideas come up — and each day, only a handful of those people take action. You have to want it. Film may be one of the most competitive industries in the world, but thankfully, the niche of action-sports filmmaking is less so. There is room for new projects and original work in the industry. Do what you can to keep your eye on that ball, and then get to work making your film.

The second most critical step you’ll encounter is scheduling your time. If you have a day job, are in school, or even focus your free time on an action sport, then you’ll have to find a schedule that works for you and is realistic. When I took an entrepreneurial course in college, numerous company founders came in to lecture on how they found success. I remember one of them in particular: Paul Orfalea, who founded Kinko’s in his garage while he was in college. In his lecture, Paul shared several basic concepts that have always stuck with me.

The first was that he put a major emphasis on time management. If you allot a fixed amount of time each day to developing your project, followed by a block of time on emails, then another block on other responsibilities, in the end, you’ll get much more done. Too often people try to spend all of their day on a project, then, when general life responsibilities get in the way, they get frustrated or stressed.

The next key thing Paul said was that because he had dyslexia, he realized early on that he needed to hire people who were smarter than he was in his weak areas. This is a key in filmmaking as well. Don’t try to do everything; instead, find someone who excels where you do not. If you know a great editor, then hire that person. If you are better at shooting than you are at producing, then find yourself a producer. If you surround yourself with good people in any project, it’s only going to elevate the quality of the project.

Finally, Paul’s story of getting started began in his garage in Santa Barbara. There was no enormous grant of money or big venture-capital fund to get him going. He took an original idea, filled a void that he saw, and did so simply and cheaply.

There is no better way to find success than to emulate those successful people who have come before us. Whether it’s an action-sports documentary you are making or a new online series of webisodes, it all starts with your concept and your time and project management.

Setting Goals and Timelines

Having a clear goal requires a solid schedule. The best way to set one up is to consider, first, how long you anticipate the entire process to take. Second, set a deadline for the final project and be realistic about it. And finally, work backward from that deadline and break down monthly goals, weekly goals — and then, if necessary, even daily goals.

If you pick a deadline and just stare at it on your calendar, you’re either going to wind up procrastinating and cramming to achieve it at the last minute, or, worse, front-load too much of the work and not give certain aspects of it the time and focus they deserve. Consider getting a calendar specific to that project. Put it in a place that you use for work and that you see regularly. Throughout the calendar, clearly label each goal deadline, beginning with small day-to-day tasks. If you’re making an action-sports documentary, then set deadlines such as finding a producer by the end of the month. Then your small daily goals might be allotting two hours a day to researching producers, the project, and other key aspects of the process. When you approach that three-week mark, be sure you’re getting close to achieving your first big deadline.

If, on the other hand, your intentions are simply to go out and shoot a video with your friends, then your goals can be as basic as shooting a minimum of six hours per week, or making sure you get to at least three different skate spots per week. It doesn’t matter what the goal is, so long as it’s realistic, you set it, and you stick to a schedule that’ll get you there.

Jack-of-All-Trades, Master of None

We’ve all heard that expression, but what we rarely hear is the end of it. The original complete epithet reads: “Jack-of-all-trades, master of none, though oftentimes better than a master of one.” Interestingly enough, the world is changing to a more complicated, more integrated place. This latter version of the saying, in its totality, puts the emphasis back on the benefit of being good at many things.

In the old days of filmmaking, a great cameraman could perhaps someday become a director of photography (DP), but never would he or she become an editor or a director. But that was then. Today, more and more filmmakers are climbing the ranks with a wealth of knowledge in all fields. From the aspiring director who is an excellent cameraman, editor, and even writer, to the action-sports filmmaker who literally does every aspect of the production alone, technology and knowledge of all fields have expanded so fast, and have become so affordable, that anyone can get involved and learn the arts.

There was a time in the past when large production companies and even studios were interested in hiring only that master of one trade. Today, countless companies are in search of young up-and-coming talent that can oversee the planning and execution of a shoot, as well as do creative work on how to incorporate web elements and other distribution opportunities.

We live in a world connected by virtual hotspots such as MySpace and YouTube; this is the stomping ground in which young filmmakers are cutting their teeth. This is also a distinctively different place from classic real-world spots: film festivals, production companies, and shooting locations. Both types of places, however, require a social and professional understanding of networking, etiquette, and skills. Twenty years ago, no one would have predicted that these two worlds would collide.

The future of action-sports filmmaking is a path that you cannot take, for it doesn’t exist yet. No one could have imagined that Tony Hawk would land that 900 at the Summer X Games so long ago, and no one would have thought that action sports would be shot on high-def 24p cameras, but this is the world we live in. Where it goes from here is up to you.

Notes

1 Avant-garde is a French term that refers to things — oftentimes films — that are artistic or experimental in nature.

2 “Computers Join Actors in Hybrids On Screen,” New York Times, January 9, 2007.

3 Even though many DPs and directors still prefer film, more and more studio features are shot each year on high-end HD cameras.