1 A History of Action Sports and Filmmaking

An Introduction

There are more than 75 million action-sports participants in the United States today, and well over 100 million fans.1 That number has been growing steadily since the mid-’80s, with no signs of slowing. So how does this affect you and your desire to shoot action sports? Significantly.

Action sports were introduced to the mainstream world in the late 1980s under the all too well-known term “extreme sports.” In 1995, one of the worldwide leaders in sports, ESPN, saw value in this growing niche and quickly founded the Extreme Games. The ensuing years demonstrated enormous growth in all disciplines — from the top-rated aggressive in-line skating of the 1990s, to the acceptance of snowboarding into the Olympics, to the now-prominent Freestyle Moto-X. ESPN and the world have continued to watch as more and more kids participating in conventional sports have steadily shifted to action sports.

Mainstream participation in this growing industry eventually led to an oversaturation of the term “extreme sports.” ESPN soon amended the formerly titled Extreme Games to the now-massive X Games. Meanwhile, what began as a “go for broke” attitude among action-sports participants was maturing into a calculated approach to executing tricks and substantially lowering injury rates. The result was the evolutionary step of kids quickly progressing from being extreme-sports participants to action-sports athletes.

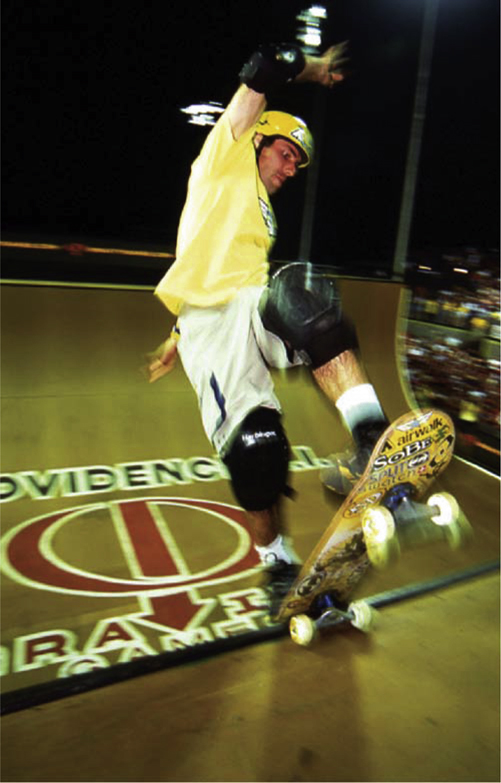

Flash to 1999. Tony Hawk stands atop an X Games vert ramp. Hundreds of cameras, professional and personal, look onward as the Best Trick finals timer counts down to the very end and Hawk fails to land his trick. Then, like a classic Hollywood story of a man fighting against all odds, with the contest over, Hawk continues to attempt his trick — again and again and again. The 900 (spinning two and a half times in the air) was a virtually unheard-of maneuver in skateboarding. If anyone was going to land it at such a prestigious event, it was going to be the godfather of the sport, Tony Hawk. Nearly every other athlete stopped skating out of respect and support for Tony. Then, after 18 failed attempts — with his fans, peers, and millions of people watching on television — Hawk dropped in once more, set himself up, and took off spinning blindly into the air. As he came around on the second rotation, this time Tony saw his landing, put his feet down, and rode away, executing the first ever 900 at the Summer X Games.

Hundreds of fans were rolling video that day. ESPN broadcast the clip to tens of millions of homes worldwide. When all was said and done, Tony Hawk’s determination had managed to elevate skateboarding more than any other single event in action-sports history. Hawk went on to build the multimillion-dollar franchise that is his name today.

The broad appeal of this event may have been made mainstream through the cameras ESPN had rolling that day, but the significance of the event revolved around one simple thing: a guy on a plank of wood trying to land a trick that few thought possible. It doesn’t matter if you’re shooting with 14 cameras on cranes, cables, and dollies, or if you’ve got a basic digital-video (DV) camera from your local electronics store. It is the heart and emotion of any trick that makes it a great moment to capture.

Figure 1-1 Dustin Miller at the LG Action Sports World Championships.

Defining Action Sports

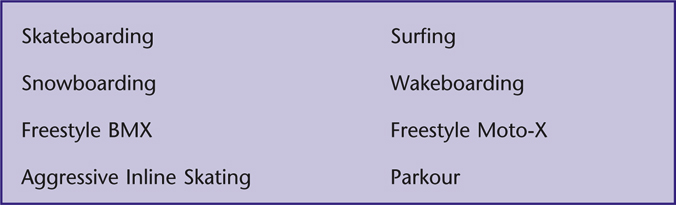

For the purpose of this book, I’ll use the term “action sports” rather broadly. Many will claim that action sports are only the aforementioned “extreme sports,” which include the following:

However, action sports can be far more than just the popular core sports. Although Webster’s defines action sports as “any athletic endeavor considered more dangerous than others …,” and even Wikipedia attempts to define action sports, there are no officially defined limitations or boundaries as to what makes one activity an action sport and another not. For example, skiing has rarely been thought of as an action sport, but if you watch the Winter X Games, you’ll now see countless young athletes hucking themselves off snowboard-sized kickers to do corkscrews and 900s, and even sliding the rails and boxes made popular in snowboard parks.

So what makes snowboarding a different action sport from skiing, which has kept its reputation as being a more mainstream sport? For starters, one of the ways many sports have been deemed “extreme” or “action” is based on the era in which they became popular. As an example, snowboarding is one of the quintessential Generation X and Y sports that has now been embraced by all generations.

Some, like Webster’s, would claim that one way to define an activity as an action sport is by the level of danger involved. Interestingly, statistics have clearly shown that the believed danger in action versus conventional sports simply isn’t true. On average, most action-sports athletes, such as skateboarders, are far less likely to receive any serious injuries than are football or basketball players. In 2005, skateboarder injuries averaged 23 per 1,000 participants, versus 38 per 1,000 participants of basketball.2 Either despite or because of its reputation as “dangerous,” the action-sports industry has settled into a stable coexistence with conventional sports. More often than not, events such as the Winter X Games skiing disciplines are being considered action sports.

Lastly, action sports can be identified by their progressive nature. There is often no clear-cut finish line; rarely can you judge winning or losing beyond pure subjectivity, and you’ll often hear professional judges throw around words such as “style” and “creativity.” These sports are always changing, always progressing. Even the best athletes in the world can’t do every trick. Although big names such as Dave Mirra, Bucky Lasek, and the Yasutokos are considered top athletes in their respective sports, that doesn’t stop a kid living in Anytown USA from inventing and naming a trick of his own. A huge part of the broad appeal of action sports is the chance to challenge the creativity of all participants, new or old, coupled with the opportunity to do so on an individual basis rather than as a team.

Illustration 1-1 Action sports vs. conventional sports.

Categorizing What You Shoot

For the purpose of simplicity, I’ve chosen the term “skaters” to use most often here and throughout the book when describing action-sports athletes. Keep in mind that all action-sports participants in every activity can be substituted on some similar level.

On a simple level, most skaters consider themselves street, park, or vert skaters. However, even subcategories exist within professional action-sports athletes: for example, video and magazine skaters, contest skaters, and big-trick skaters. The differences are as follows:

Video and magazine skaters are most often street skaters who are well respected for their technical grind, slide, and flip tricks. These pro skaters usually film parts for the upcoming videos over the course of weeks or sometimes even months. A trick here and a trick there — they are doing the most progressive and best of what’s out there. Because these trick skaters are often doing such technical or difficult tricks, it can sometimes take them 10 or 20 tries to make their latest trick. This, of course, isn’t true of all athletes — but more often than not, if you’re shooting this style of skater, be prepared to stay involved with them for a number of tries. We’ll dive into this more in the section on cameraman/athlete etiquette.

These “video skaters” are usually featured in annual or quarterly released skate videos such as 411 Video Magazine or their latest upcoming pro-team video. They may have a few tricks in a music-driven montage section of the video, or they may have their own section consisting of dozens of tricks all cut to a single song. Either way, these skaters are not seen as often on television, and thus don’t usually have the mainstream awareness that contest or vert skaters have.

This brings us to the next group of athletes — the contest skaters. These athletes pride themselves on consistency, and though they don’t all like to admit it, they usually have some form of mainstream appeal. Standing atop a 17-foot-high roll-in with no one else on the ramp as half a dozen cameras shoot you for TV, and thousands of people in the crowd watch live, is no easy feat, and it’s certainly not for everyone. Top contest athletes such as Brazilian skateboard X Games gold medalist Sandro Diaz or world champion in-line skater Eito Yasutoko have made a career out of sticking their tricks back-to-back ten out of ten times. These athletes are usually ramp (or transition) skaters, and wind up with some of the bigger endorsement deals, given the number of eyeballs that see them on TV versus the number of kids watching skate videos at home. The downside, however, is that it takes a good skate park to practice at, and not every city has one — whereas almost every town in America has a decent handrail and parking lot curb that people can session on.

Figure 1-2 Andy Mac sticks a frontside blunt (photo by Todd Seligman).

Last are the big-trick skaters. These are the athletes that first made a name for themselves by doing huge — or what some might consider crazy — stunts. These are the guys or girls who virtually redefine the word “extreme” with what they do. Be it street or ramp skaters, park or backcountry snowboarders, or even downhill mountain bikers, in every action sport, there are a handful of people pushing themselves to — and often beyond — the edge of calculated risks. In 1995, Freestyle BMX legend Mat Hoffman built a 25-foot-high quarter-pipe in his backyard and was towed into the ramp across a plywood runway by a street motorcycle. His 42-foot air is in the Guinness World Records. In 1998, in-line vert skater turned pro snowboarder Matt Lindenmuth landed the first ever — in any sport — double backflip on a vert ramp. Finally, the pioneer of the X Games Big Air event, Mr. Danny Way himself, had VPI Industries reconstruct his mega-ramp in Beijing, where a lifetime of impressive athleticism culminated in Way’s jumping the Great Wall of China — and in many respects, he’s just getting started.

Figure 1-3 Danny Way’s Great Wall of China jump (courtesy Todd Seligman).

These athletes are professionals in their own right. In every sport, you will find athletes who will more or less fit into one of these categories. Occasionally, you will find the great ones who will cross over to two or even three of them.

To sum it up, the kids read the magazines and watch the skate videos, the world sees the contest skaters on TV, and almost everyone pays attention when a stunt is performed. Still, the question remains: What will you shoot?

Although there are athletes who encompass more than one of these categories, understanding how to shoot in different environments will help you create the shots you want. In later chapters, we will review techniques and methods for shooting the different styles. The categories can — and do — expand far beyond the three main ones here; many athletes live outside of these, especially amateur and recreational athletes. Keep in mind that if your subject isn’t a professional, he or she may not even be affiliated with any one category. But if you are shooting pros, then the following section will be a great help in understanding the pro-athlete mind-set.

Cameraman/Athlete Etiquette

When most action sports formed, they did so by chance, as more and more individuals fell in love with the sport and took it up. Very few, if any, professionals will tell you they started in their sport for the purpose of becoming a pro or making money. As a result, many people consider action sports more of a lifestyle than an actual sport. Because of this, if you attend a major contest, you’ll see most athletes cheering for their buddies who are competing against them. Why? Because most riders compete against themselves, constantly trying to aggrandize their own ability levels and push their own limits.

Many cameramen go to major events or popular skate spots to shoot professionals, not necessarily knowing them personally. The most common mistake videographers and filmers make at these events is thinking that what they are doing is more important to the athletes than it usually is. So if you ever find yourself filming at a contest, demo, or any similar type of venue, keep in mind the following: if the event wasn’t set up, and if the pros weren’t flown in specifically for the purpose of your shooting them, then you are most likely not their priority.

If it weren’t for the television and mainstream media coverage, these events wouldn’t have the sponsorship dollars they need in order to take place. However, that’s where the chicken-and-egg similarities end. In action sports, the footage we often get is dependent on our abilities to work with or around the riders and what they are doing. Very often a pro rider will land a trick — and if you miss it, it’s simply too late. The option always exists to approach the athlete and ask if they’ll do it again for you. Many times, athletes will be fine with this as long as you ask politely and you’re cool about it. Occasionally, however, they may be tired or just ready to move on. Of course, if you know the rider, this is a nonissue. It’s when you don’t know the athlete that it’s important to be respectful. Imagine if it were you just doing something you love — and everywhere you go, people keep shoving cameras in your face and telling you what to do.

Figure 1-4 Cameramen shoot pros at a contest.

Pacing yourself for the sake of the athlete is also helpful. You can balance out how often you get in their face with the camera. Start farther back, then slowly work your way in. Take a break, then go farther back again. For example, if you have a wide lens, use it for those close-up action and character shots, but then take it off every so often and find a cool long-lens distant shot (more on this in Chapter 6, Shooting Techniques). This method will help a good deal in keeping the relationship between you and the athlete positive and respectful.

The second scenario may include your working with an athlete you know or have gotten to know at an event. If you set out to film a trick with someone specific, they will have certain expectations from you. There is a unique bond between cameraman and athlete that happens in action sports. In many respects, the entire dynamic shifts the moment they commit to getting a trick or many tricks for your camera. Like the video skater described above, athletes will try over and over again, working with you to get the trick on camera — whether it’s for a video, a documentary, or even just the personal satisfaction they’ll get from sticking it.

Skaters may look to you for encouragement to help keep them pumped up about landing a trick. This is where the bond forms. It becomes your job even as a cameraman to see that trick through as the skater tries over and over again. Although it’s rarely said, it’s disrespectful to walk away and stop shooting before a trick is landed if you’ve been invited to shoot it by the athlete. Keep in mind that of course this is not always the case, and most that athletes will understand if they’ve been at it for a while and you need to go. The key is to feel the energy, and if you want to stop, just be polite and ask.

I learned this lesson in reverse early on in my career when I was shooting a team video for Salomon in Europe. We were at a skate park in Germany, and I had been shooting video of various tricks and locations with the team all day. It was getting late in the evening, and I was tired. One of the athletes, Jake Elliot, was also a friend. Jake was trying a trick on the street course and working with me to get it on video. It was just the two of us. Like myself, Jake was getting tired. Eventually, I stopped getting excited, and it was more than clear to Jake that I was mentally done, trying to stay in it just for him. Finally, he approached me and said that he could tell I wasn’t into it, and my lack of energy was bringing him down. He suggested I go crash and hand the camera over to a friend to help see the trick through. This was the first moment when I realized just how strong the relationship between athlete and cameraman can be.

Figure 1-5 Athletes and cameramen.

At any major event, the camera team is very often composed of a combination of professional sports cameramen and more-casual unobtrusive DV or high-definition-video (HDV) cameramen. In the late ’90s, some athletes were very disrespectful to filmers. Early on in the sports, for every professional Tony Hawk type, there were at least two, if not more, unprofessional athletes. This latter category often said that the camera guys were there only because of them, and that therefore the cameramen should stay out of their way — out of sight, out of mind, if you will. But then the camera guys had the attitude of, “We shoot big events, and these are just some punk kids.” The result was a lack of overall good coverage and a distant feeling from the athletes. People at home watching TV — or later, the event on DVD — may not have been able to identify what it was, but they could feel this separation. Eventually, most athletes and cameramen came to realize that these events weren’t going away, and that if they work together, they’ll get better shots on TV, which benefits everyone. Today, many athletes and cameramen are even great friends and go out together after the events. But the undeniable lesson learned here is, again, one of respect; it goes both ways and has to start somewhere. When skater and cameraman work together, the shots get more exciting, the material gets more compelling, and the odds of a successful shoot increase astronomically.

Figure 1-6 Classic early ’90s bumper sticker.

The Bumper Sticker Syndrome

When I was 8, someone handed me a bumper sticker that read, “Skateboarding is NOT a Crime.” I remember thinking to myself; “I’d get in trouble if I put this on my dad’s car.” Of course, it wasn’t until I grew up that I realized the irony in this. By then, skateboarding was no longer viewed as a crime — well, at least not as much.

There are more public and private skate parks in the United States than in any other country in the world — and the number increases every day. Dreamland is building massive concrete skate parks funded by taxpayers across the Northwest, Tom Noble’s SPC began with the legendary Ratz Skatepark in Maine and now builds killer parks in the Northeast, and so on. The industry has come a long way since the ’80s, when skateboarding began its biggest resurgence in history. Watching the Sundance Film Festival award-winning documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys will show you the birth of skateboarding, along with some great filmmaking. It wasn’t until the 1980s, however, that the sport finally went through what many hope was its final major hurdle of mainstream acceptance.

Like most industries, in order to garner the attention of the public, it’s often thought that any publicity is good publicity. It took a catchy slogan on a bumper sticker — ”Skateboarding is NOT a Crime” — to help do this for skateboarding, along with the small-town slogan of almost equal power, “Support Your Local Skateboarder.” These sayings helped make some progress against critics who are still being fought today, although on a much smaller level. Just because it’s done in the streets, and not in a field or on a court, doesn’t make it a crime.

Figure 1-7 Early 1990s skate park.

An interesting twist on this came in the mid- to late 1990s when the popular aggressive in-line clothing company Senate decided to release an entire line with laundry tags that read on the back, “Destroy all Girls.” In the case of Senate, whether this was an attempt at making their sport appear more outlaw, a simple marketing ploy for publicity, or even just a creative outlet for their designers, it put Senate on the news across the country. The company quickly issued an apology, discontinued the tags, and went on to break every one of their previous sales records.

It’s clearly apparent that even bad publicity can be good, but it will always take an event as positive and as significant as Tony Hawk’s 900 to make any lasting impact. The public’s opinion of the industry is shaped by how that industry is presented in the media. Although marketing schemes and bumper stickers have helped create public awareness, it’s what you film and how you present it that will most often shape how people view that sport.

Modern Forms of Filmmaking

The argument goes like this: one filmmaker says, “3-D is going to save the movie theaters,” then the other argues that “nothing will save them as downloading and home theaters get better, faster, and cheaper.” Either side you take, there’s no denying that a once-standardized industry is going through enormous changes for the first time in history.

Since the early 1900s, cameras and filmmaking have been relatively unchanged, with the exception of sound and color being added in. Now, almost 100 years later, we are witnessing the first technological advancement in filmmaking, and it’s happening at blistering speeds. From Betamax video to DV cameras, HDV, and high definition (HD), there’s no doubt that you now have choices out there in what you shoot. Chapter 2 will dive into these options more completely.

The face of filmmaking is becoming that of a faster, easier, cheaper medium that is resulting in more and more people picking up cameras to shoot their first — or 100th — short film or action-sports documentary. The result is more, better films and videos on the web and in stores.

Independent filmmaker Robert Rodriguez (Desperado, Spy Kids) is in many respects the best do-it-yourself filmmaker of our time. He has pioneered technologies in films such as Sin City, and has shown us that big-budget action films (for example, Once Upon a Time in Mexico) can be shot on high-def digital cameras near single-handedly. Rodriquez is notorious for writing, shooting, directing, producing, editing, and scoring his own films — basically a bigger-budget version of what many action-sports filmmakers are doing today. You buy a camera, come up with a concept, shoot it, cut it, and — voilà — your own film that you can distribute on the web or on DVD.

Figure 1-8 Robert Rodriguez on the set of Planet Terror (Grindhouse) (courtesy Dimension Films, photo by Rico Torre).

On the flip side, many TV networks are keeping their structures of large film crews, and are just switching the format of shooting to adapt these faster, cheaper technologies such as DV, HDV, and HD. In both cases, the cost is coming down, and the quality is going up. This means that if your filmmaking is more than just a hobby, if you do any level of production with intent to distribute, then you are more and more likely to find success as studios and networks open their arms up to unestablished filmmakers such as once-unknown Robert Rodriguez.

The modern forms of filmmaking are still evolving, so if you want a leg up, it is key to stay current with the technologies. Just remember: anyone can read the manual from the newest camera and then press that red button and start operating, but that doesn’t make them a cameraman.