C H A P T E R F O U R

CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

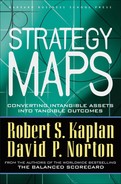

CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT reflects much of what is new in modern business strategy (see Figure 4-1). In the Industrial Era, strategies were product driven: “If we build it, they will come” was the underlying philosophy. Companies succeeded through efficient operations management processes and product innovation. Operating processes, focused on cost management, scale economies, and quality, enabled products to be delivered at prices that generated attractive profit margins while still being affordable to customers. Innovation processes produced a continual flow of new products that helped to grow market share and revenues. Customer management focused on transactions—promoting and selling the enterprise’s products. Building customer relationships was not a priority.

The new economy has heightened the importance of customer relationships. Whereas innovation and operations management processes remain important for strategic success, the evolution of computer and communications technology, particularly the Internet and database software, has shifted the balance of power from producers to customers. Customers now launch transactions. They lead rather than reacting to marketing or sales calls. For example, customers of Dell and Levi Strauss can design their own product configurations using the companies’ Web sites—Dell.com and IC3D.com (for blue jeans). Customer purchases, recorded at point-of-sale terminals at Wal-Mart, trigger production runs at vendor locations. Customers can find valid information about a company’s products, including price, availability, features, and delivery times, on the Web. Chat rooms provide testimonials from satisfied as well as dissatisfied customers.

Figure 4-1 Customer Management

Physical proximity of customers to the company is frequently not critical. Overnight shipping companies, such as FedEx, DHL, and UPS, allow products to be shipped to customers’ places of business or homes from production sites scattered around the world. An organization can no longer define the success of its customer management process as merely generating a transaction, a sale. Customer management processes must help the company acquire, sustain, and grow long-term, profitable relationships with targeted customers.

FOUR CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

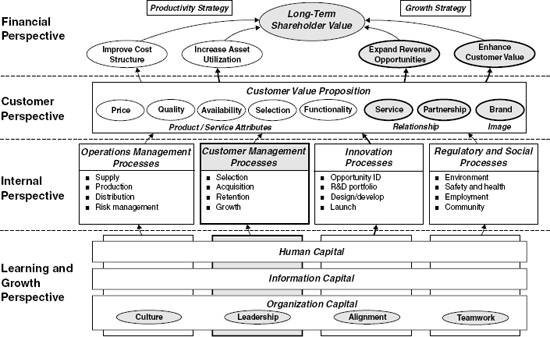

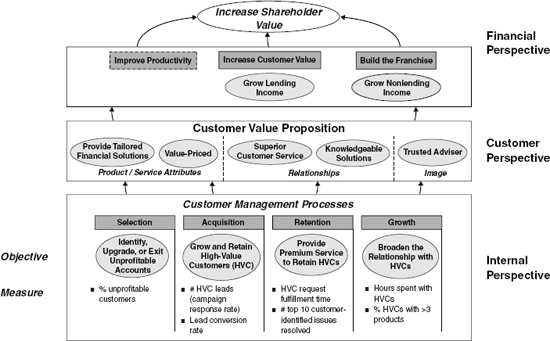

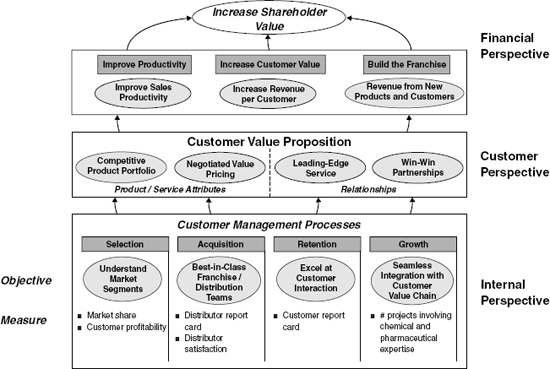

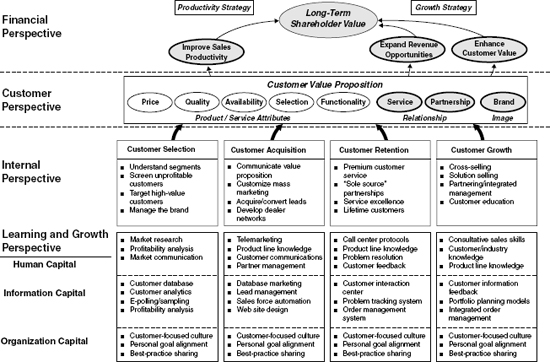

Customer management consists of four generic processes (see Figure 4-2):

- Select customers: Identify customer segments attractive to the enterprise, craft the value proposition to appeal to these segments, and create a brand image that attracts customers in these segments to the company’s products and services.

- Acquire customers: Communicate the message to the market, secure prospects, and convert prospects to customers.

- Retain customers: Ensure quality, correct problems, and transform customers into highly satisfied “raving fans.”

- Grow relationships with customers: Get to know customers, build relationships with them, and increase the company’s share of targeted customers’ purchasing activity.

Customer management strategies should include execution along all four processes. Most organizations, acting without an explicit customer management strategy, do poorly on selection and retention processes (numbers 1 and 3). For example, Mobil pursued a confused pricing strategy for many years because it did not segment and target its vast market of potential consumers. Chemical Bank (now part of J. P. Morgan Chase) also lacked direction from a clear market segmentation strategy. It cultivated relationships with many unprofitable customers. Many organizations also pay too little attention to retaining customers. They treat sales as transactional events, avoid contact with their customers after the sale, and fail to measure whether they retain them for future business.

Figure 4-2 Customer Management Processes

1. Customer Selection

The customer selection process starts with segmenting the market into niches, each with distinguishing characteristics and preferences.1 The executive team selects target segments where the company can create a unique and defensible value proposition. Customer selection is not the same as order selection or pricing (“should we take this order?”; “at what price?”). Customers differ greatly in their profitability, and companies typically spend a great deal of money developing and nurturing customer relationships that can last for many years. To ensure that their marketing and sales investments are directed at the most profitable opportunities, executives should spend as much time and effort on selecting and investing in targeted customers as they do in selecting their investments in property, plant, and equipment. They should avoid the trap of trying to be the best supplier to all their possible customers.

Customer segmentation should ideally be done based on the customer value proposition, that is, the benefits customers desire from the product or service. Customers can be segmented by the benefits they seek or their relationship to the company, such as:

- Use intensity: Heavy, light, none

- Benefits sought: Price, service, performance, relationship, brand identity

- Loyalty: None, moderate, strong, committed

- Attitude: Dissatisfied, satisfied, delighted

In practice, especially in mass consumer markets, customer preferences can be difficult to observe directly, so segmentation is often done on more easily observable characteristics. For example, consumer segments can be defined by:

- Demographic factors: Age, income, wealth, gender, occupation, or ethnic identity

- Geographic factors: Nation, region, urban or rural setting

- Lifestyle factors: Value-oriented, luxury-oriented

Of course, segmentation on observable characteristics is valuable only if the characteristics correlate with the underlying preferences of customers. Advanced statistical techniques can be used for developing such valid segmentation in a heterogeneous population. These include cluster analysis for identifying homogenous customer segments, conjoint analysis for measuring customer preferences and needs, and discriminant analysis, for separating customers into distinct segments.

Once companies identify possible customer segments, they select targeted segments. A company’s choice of customers can influence its capabilities, and, conversely, a company’s resources, capabilities, and strategy can determine its best customers. For example, automobile component manufacturers for the “big three” U.S. automakers that subsequently became early suppliers to Japanese automakers (Honda, Toyota, and Nissan) became trained in Japanese total quality and just-in-time production processes. They soon became more differentiated suppliers and could compete on capabilities, not just price. As another example, a specialty, low-volume producer might get asked by a customer to produce a standard product in extremely high volumes. Such a customer order would begin the transformation of the company from a niche producer to a mass producer, with a very different cost structure.

In the more typical process, the company’s strategy influences its choice of customers. Cigna Property and Casualty, as part of its turnaround strategy to become a specialist provider, would bid on business only when it judged its knowledge of the underwriting risks to be superior to the industry average. Dell Computer focused initially on sophisticated corporate customers who could provide local technical support for their installed base of personal computers. This focus on educated, corporate accounts enabled Dell to sell and ship directly to end-use customers, without requiring a retail or wholesale distribution channel. Dell also avoided the need to have an extensive technical support base for its customers. In this way, Dell could be the lowest-cost supplier of personal computers in the industry and soon became the industry leader.

Harrah’s Entertainment, an operator of gambling casinos around the United States, targets the “low rollers,” much like Southwest and other discount airlines target price-sensitive air travelers. Harrah’s wants to be the casino of choice for couples on their evenings out to experience the “feelings of anticipation and exuberance” from small-stakes gambling that gives them a “momentary escape from the problems and pressures of their daily lives.” Harrah’s estimated that 26 percent of its players provided 82 percent of revenues, with avid players spending $2,000 annually. Such “avid experienced players,” who could visit Harrah’s casinos in multiple locations, became the company’s targeted customers and removed it from direct competition with the high-cost luxury casinos operated by Mirage Resorts and Circus Enterprises.2

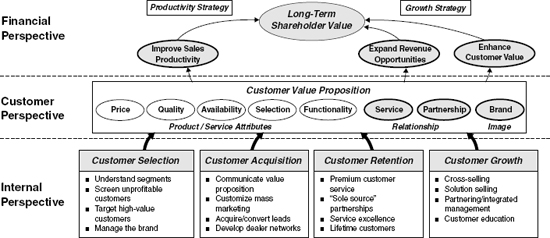

Marine Engineering’s new strategy (see Figure 4-3) deemphasized a large customer segment that was highly price sensitive. It identified, for future growth and profitability, a market segment of customers that (1) valued long-term partnerships with suppliers, (2) wanted to outsource noncore services, and (3) asked suppliers to share in their risk and rewards from major projects. Marine Engineering would get paid more if its projects yielded higher returns for customers; its fees would be penalized when projects were late and above budgeted cost.

Figure 4-3 Case: Marine Engineering

Marine Engineering chose a customer selection objective to “focus only on strategic accounts,” those where business could be won by offering value-added services superior to those offered by competitors. It measured success for this objective by the number of customers whose business could be won based on superior services and relationships rather than low price. It also measured the frequency of not pursuing all potential business, particularly from customers who were seeking the lowest price bid. It used a measure—number of no-bids—to signal clearly that not every sales opportunity was to be pursued.

Some companies, especially in mature, commodity-type industries, do not see significant opportunities for growth through value-added services. The selection process for these companies focuses on avoiding unprofitable customers, those who use services costing more than the fees and revenues they generate. Metro Bank (see Figure 4-4) and Acme Chemicals (see Figure 4-5) both had significant but stable market shares. They chose an objective to “identify and then upgrade or exit unprofitable accounts.” Using activity-based costing to measure profitability at the individual customer level, they measured their success in reducing the percentage of unprofitable customers.

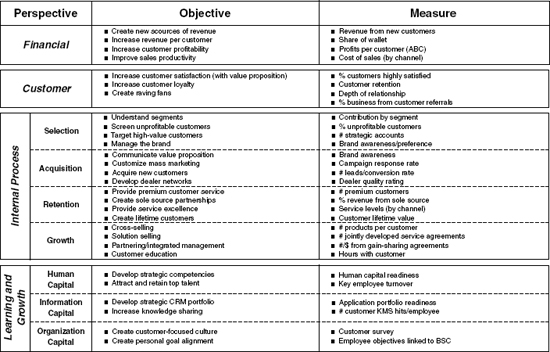

Typical objectives and measures for customer selection processes are shown in the table below:

| Customer Selection Objectives | Measures |

| Understand customer segments |

|

| Screen unprofitable customers |

|

| Target high-value customers |

|

| Manage the brand |

|

Figure 4-5 Case: Acme Chemicals

2. Customer Acquisition

Acquiring new customers is the most difficult and expensive customer management process. Companies must communicate their value propositions to new customers in the segments targeted by their customer selection processes. The company could initiate the relationship with an entry-level product that might be a loss leader, or a heavily discounted product. Ideally, an entry-level product should be inexpensive enough that the customer does not face much risk from purchasing it. The product should represent an important solution to the customer so that success makes a significant impression on the customer. The product’s quality should be perfect so that the customer does not experience defects or failure with its initial purchase. And the performance of the product can be enhanced and complemented by additional products and services that can be sold to the customer in the future (using customer growth processes). For a financial service company, a checking account or a credit card represents an entry-level product with all these characteristics. For an insurance company, providing insurance on risks with high frequency of claims but low value per claim allows the customer to rapidly gain experience with the company’s claim-handling processes and to build confidence in the company’s ability to be a superior provider of insurance services.3 Harrah’s identified its targeted “low roller but loyal” customers with an extensive database marketing system. It sent special offers—such as $60 in chips—to attract its targeted customers for their initial visit to a Harrah’s casino.4

Marine Engineering, dealing with a relatively small number of potential customers (twenty to thirty), developed an education program to show potential customers the benefits from gain-sharing partnerships. Marine measured its success rate on new proposals with these customers. Metro Bank launched a major sales campaign directed at the high-value customer (HVC) segment. It measured the number of leads generated by the program and its effectiveness in converting such leads into active customers (the lead conversion rate).

Acme Chemicals sold about half of its business through distributors. It monitored the quality of each dealer’s customer acquisition performance through a periodic report card. It also received a feedback survey from dealers that evaluated, among other attributes, the quality of Acme’s brand-building, advertising, and lead creation.

Typical objectives and measures for the customer acquisition process are shown below:

| Customer Acquisition Objectives | Measures |

| Communicate value proposition |

|

| Customize mass marketing |

|

| Acquire new customers |

|

| Develop dealer/distributor relationships |

|

3. Customer Retention

Companies recognize that it is far less expensive to retain customers than to continually add new ones to replace those who defect. Loyal customers value the quality and service of the company’s products and are often willing to pay somewhat higher prices for the value provided. They are less likely to search for alternatives, thereby significantly raising the discounts that a potential competitor must offer to attract customers’ attention.

Companies retain customers, in part, by consistently delivering on their primary value proposition, but also by ensuring service quality. Customers may defect from organizations that are not responsive to requests for information and problemsolving. Companies must develop capabilities, such as in customer service and call center units, to respond to requests about orders, deliveries, and problems. These units maintain customer loyalty and reduce the likelihood of customer defections. A company can measure its customer loyalty by whether customers are spending an increasing “share of their wallet” on repeat purchases.

The key to Harrah’s success is its customer loyalty program. It issues its customers loyalty cards, called Total Gold cards, that enable the company to track customers’ playing preferences, betting patterns, eating preferences, use of the hotel facilities, frequency of visits, and extent of play per visit. Harrah’s runs experiments to learn how to increase loyalty and intensity of use of the company’s facilities. It deploys direct marketing programs, such as a Total Rewards program, similar to an airlines’ frequent flyer program, that provide rewards based on total business conducted at Harrah’s locations. The rewards help in cross-marketing by encouraging loyal customers to earn and redeem rewards at any of Harrah’s properties across the country. As CEO Gary Loveman noted, “The more we understand our customers, the more substantial are the switching costs that we put into place, and the farther ahead we are of our competitors’ efforts.”5

Even more valuable than customer loyalty is customer commitment, which occurs when customers tell others of their satisfaction with the company’s products and services. Committed customers are also more likely to provide feedback to the company about problems and opportunities for improvement than to defect to competitors when dissatisfied. Companies can measure customer commitment by the number of suggestions made by customers, by the number of referrals existing customers make to new customers, and by the number of new customers acquired based on such referrals. Customer apostles are special cases of highly credible and authoritative committed customers. For example, Wal-Mart’s recommendation that a supplier is reliable, high-quality, and responsive will carry considerably more weight than a comparable statement made by a local retailer. Being a qualified supplier to Toyota provides credible testimony to the company’s ability to produce low-cost, zero-defect products and deliver reliably within a narrow time window. The highest form of loyalty occurs when customers take on ownership behavior for the company’s products and services. Customer owners participate actively in the design of new products and supply recommendations on enhancements for service delivery. For example, Cisco Systems has followed recommendations from customers to acquire new capabilities through the purchase of other organizations. Frequent flyers of Southwest Airlines can participate in screening new cabin attendants. Customers who act as apostles or owners can provide far more lifetime value than a large number of merely loyal customers who maintain or even expand their purchasing behavior but do not recruit new customers or provide ideas for product and service improvements.6

Marine Engineering measured the strength of its customer partnership strategy by the number of sole-sourcing relationships, in which it won and retained business without submitting to competitive bids. Metro Bank monitored the service levels (request fulfillment time) for its high-value customers. It also surveyed key customers every six months to assess their satisfaction with the bank’s performance in resolving their top issues of concern. Acme Chemicals introduced a Customer Report Card to gain feedback from its industrial customers. In each of these cases, the company’s customer retention strategy consisted of providing superior service, actively soliciting and listening to customers’ feedback, and building relationships that made it costly for customers to defect.

Typical objectives and measures for the customer retention process are shown in the table below:

| Customer Retention Objectives | Measures |

| Provide premium customer service |

|

| Create value-added partnerships |

|

| Provide service excellence |

|

| Create highly loyal customers |

|

4. Customer Growth

Increasing the value of the company’s customers is the ultimate objective of any customer management process. As already noted, acquiring new customers is difficult and expensive, and only makes sense if the size of the ensuing relationship exceeds the cost of acquisition. Acquiring new customers with entry-level products means that companies can expand their share of the customers’ purchases by providing other, higher-margin products and services to them. Organizations should actively manage the lifetime values of their customers.

A company that can cross-sell and partner with customers expands its share of the customers’ spending in the category. Increasing the depth and breadth of the relationship enhances the value of customers, and also increases the customers’ cost of switching to alternative suppliers. One way to expand the relationship and also differentiate a basic product or service is to provide additional features and services after the sale. For example, companies can provide field service that performs remote monitoring of expensive equipment at the customer’s location. Such monitoring enables the field service team to anticipate when unexpected failures are about to occur, and perform the maintenance that will prevent such failures and equipment downtime. The diagnostic monitoring and preventive maintenance adds considerable value to customers. It not only generates high customer retention; it also provides an attractive, high-margin revenue stream to the company. As another example, a commodity chemicals company was able to differentiate its basic product by providing a service that picked up used chemicals from customers so that it could reprocess the chemicals for disposal or reuse in an efficient process that conformed to environmental and safety regulations. This service relieved many small customers from expensive environmental processes and regulatory oversight.

Companies can partner with their customers, developing specific solutions for their targeted customer needs. For example, Marine Engineering attempted to lock targeted customers into sole-source partnerships by creating an integrated management system with them. Metro Bank measured success in its customer growth objective by the number of high-value customers who used more than three of the bank’s services. It expected that establishing more personal, knowledgeable relationships, measured by the number of hours spent with customers by the relationship manager, was a driver of this desirable outcome. Acme Chemicals used a similar lock-in strategy by creating knowledgeable account managers who could work credibly and seamlessly with targeted customers. It measured the number of projects where such expertise could be leveraged into lock-in relationships.

Typical objectives and measures for customer growth are shown below:

| Customer Growth Objectives | Measures |

| Cross-sell customers |

|

| Solution selling |

|

| Partner with customers |

|

CUSTOMER PERSPECTIVE LINKAGES

Customer management processes focus on the relationship and image dimensions of the basic customer value proposition (see Figure 4-2). Brand image helps both to select customers and to acquire them. Customer retention and customer growth processes build relationships with targeted customers. Our three general cases illustrate these points.

Marine Engineering’s targeted customers had an overarching objective—engineering designs and construction projects that lowered their cost of recovering oil. Marine’s selection and acquisition processes targeted customers who desired a partnership with suppliers. The processes paid less attention to customers whose sourcing decisions would be made mainly by price. Marine also wanted to build an image as a superb systems integrator, capable of managing across the life cycle of complex engineering projects: design, development, procurement, fabrication, installation, logistics, operations, and maintenance. Its retention and growth processes would deliver a seamless, integrated management process across these diverse projects and services, with a sharing of goals and rewards.

Metro Bank’s value proposition was a relationship between an account representative and a client, enabling the bank to offer a portfolio of financial products and services tailored to individual client needs. The bank expected this value proposition to be attractive to a market segment of high-value customers (HVCs). Metro’s selection process delivered a message to HVCs to establish the bank’s image as a trusted financial adviser. Its acquisition process established relationships with clients who desired a knowledgeable adviser who could build customized financial solutions. Customers using more of the bank’s solutions were the foundation for the growth process. And superior customer service would support the retention process.

Acme Chemicals competed in a mature market with a limited number of potential customers. Acquiring new customers was not a major objective. Acme’s goal was to increase its account share with existing customers. The customer value proposition was to offer a portfolio of products and services at negotiated, but still competitive, prices. Its retention process focused on the customer’s desire for leading-edge service, while its growth process focused on establishing win-win partnerships.

A typical set of objectives and measures for the customer perspective is shown below:

| Customer Objectives | Measures |

| Increase customer satisfaction through an attractive value proposition |

|

| Increase customer loyalty |

|

| Create raving fans |

|

FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE LINKAGES

The financial outcomes from successful customer management processes show up primarily in revenue growth objectives (see Figure 4-2). Customer selection and acquisition provide new revenue sources, especially when companies are moving into new markets and adding new products and services. Financial measures include sales from new products and revenue mix versus target. Customer retention and customer growth processes should yield increased customer value. Desired outcomes from these processes included an increase in share of customers’ wallet (spending) captured by the company and extent and length of relationship (lifetime customer value). In addition to these revenue growth objectives, however, effective customer management can contribute to a company’s productivity objectives through the use of sales force automation and electronic marketing.

Typical financial objectives and measures for customer management processes are summarized in the table below:

| Financial Objectives | Measures |

| Create new sources of revenue |

|

| Increase revenue per customer |

|

| Increase customer profitability |

|

| Improve sales productivity |

|

LEARNING AND GROWTH LINKAGES

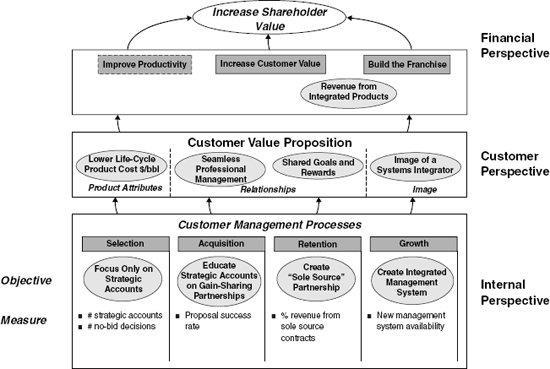

Effective customer management processes require strong, enabling support from information technology, employee competencies, and culture and climate, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Human Capital

Advances in information technology and communication have generated the potential and, now, the expectation for heightened levels of customer marketing and services. This, in turn, has created a demand for new employee competencies. Employees with knowledge of database marketing, data mining, customer analytics, call centers, customer interaction centers, and Web page design now play a crucial role in customer management processes. Even the traditional salesperson has been transformed into a strategic partner who helps customers design the portfolio of solutions for their problems and needs.

Figure 4-6 Learning and Growth Strategies for Customer Management

Each of the strategic processes shown in Figure 4-6 requires a strategic job family, with a new set of competencies. (Strategic job families will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.) Customer selection requires the analytic skills typically associated with the marketing function. Customer acquisition is built around communication and negotiation skills. The ability to know the customer environment, understand customer needs, craft a value proposition, and close the sale are fundamental to customer acquisition. These can be applied in face-to-face discussions and through telemarketing channels. Managing service quality and delivery-level management are essential competencies for customer retention. Service excellence requires two-way communication and rapid resolution of questions and problems. Relationship management is the foundation for effective customer growth. Building an enduring customer partnership requires knowledge of the customer’s organization, industry, and specific job. Excellent consultative and problem-solving skills are essential.

Information Capital

Information technology creates dramatic new possibilities for customer management processes. Information technology and related analytic techniques, such as data mining and activity-based customer profitability measurement, enable organizations to develop customized, personalized approaches even with millions of customers. Lands’ End, for example, mails different catalogs to different customer segments. 1-800-Flowers.com automatically reminds customers of important dates. Amazon.com monitors individual sales and recommends books similar to prior purchases and those purchased by similar customers.

Many new capabilities are embedded within integrated customer relationship management (CRM) systems. Customer databases and related analytics permit better customer selection through cluster analysis from demographic data and customer profitability analysis. Database marketing supports the telemarketing process to improve customer acquisition. Operational CRM systems improve sales effectiveness through sales force automation and lead management. Customer service centers and self-help capabilities enhance customer retention. The Internet permits a new level of networking with customers that enhances education, collaboration, and customer growth.

Organization Capital

Customer management processes often require a new organization climate. One feature is creating a customer-centric culture. Take the example of a major oil company that had a long-standing marketing policy for its logo to appear on every product it sold. In the mid-1990s, this company, like Mobil, entered the convenience store business. It introduced a coffee island as part of its new retail space. For months, senior management insisted that coffee cups adhere to policy by bearing the company’s familiar product logo. Only after expensive market research revealed that coffee drinkers prefer their coffee cups to display a recognized coffee brand, such as Starbucks, rather than a picture of an oil can, did senior management reluctantly change its policy. The culture of a product-driven company is deep-rooted, but must be overcome.

Customer management processes also demand a much higher degree of teamwork. Creating a lifetime customer means that many individuals must deal with the customer over time. The salesperson makes the initial transaction, the solutions engineer or relationship partner designs a portfolio of products and services, and the call-center help desk respondent provides follow-up. These diverse employees must all share the same base of information and work toward the same goals. Alignment to a common goal focuses all employees to work toward common, customer-based objectives. Team-based incentive systems and knowledge sharing networks reinforce the work of customer-focused teams, and reward all when the common customer objectives are achieved.

A typical set of learning and growth objectives and measures for customer management strategies is shown in the table below:

SUMMARY

Customer management processes in the internal perspective provide the capabilities for the organization to select, acquire, retain, and grow business with targeted customers. Understanding customers and the value proposition that attracts and retains them is fundamental to any strategy. Organizations whose internal process objectives focus only on quality, cost reduction, and efficiency are likely neglecting processes that would enable them to earn higher margins and grow their businesses. Figure 4-7 summarizes this chapter by showing a template of representative Balanced Scorecard objectives and measures for customer management processes.

In the case study following this chapter, we present the Handleman Company strategy map. Handleman, a large music merchandiser and distributor, used the strategy map to communicate and implement its new strategy based on forging long-term value-adding partnerships with its large retail customers, such as Wal-Mart and Best Buy.

NOTES

1. Helpful material on customer selection has been drawn from D. Narandas, “Note on Customer Management,” Note 9-502-073 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2002), and R. Dolan, “Note on Marketing Strategy,” Note 9-598-061 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2000).

2. R. Lal, “Harrah’s Entertainment Inc.,” Case 502-011 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2002), 7, 9.

3. This discussion of entry-level products is drawn from the “foot-in-the-door” strategy described in D. Narandas, “Note on Customer Management.”

4. Lal, “Harrah’s Entertainment Inc.,” 9.

5. Ibid.

6. The hierarchy of customer loyalty is due to J. Heskett, “Beyond Customer Loyalty,” in Managing Service Quality, vol. 12 (Bradford, UK: MCB University Press, 2002).

Figure 4-7 Customer Management Scorecard Template

CASE STUDY

HANDLEMAN COMPANY

Background

Handleman Company (HDL) is one of the world’s largest category managers and distributors of prerecorded music. HDL manages this category in more than 4,000 retail stores on three continents. Headquartered in Troy, Michigan, HDL generates $1.3 billion in annual sales and employs approximately 2,400 people worldwide, including 1,000 sales representatives. In the United States, HDL distributes more than 11 percent of all music sold. Its customers include mass merchant retailers, such as Wal-Mart and Kmart, as well as other large retailers such as Best Buy. HDL also owns Anchor Bay Entertainment, an independent home video label that markets a large collection of popular titles on DVD and VHS. Anchor Bay’s library of titles ranges from children’s classics to exercise to suspense and horror.

In calendar 2000, after several years of growth, sales in the music industry began to decline. Reasons for the decline include illegal file sharing over the Internet, competition for consumers’ entertainment spending from DVDs and computer games, and the lack of hit records that sell millions of units within weeks of their release. To maintain its leadership position in category management and distribution, HDL focused on a strategy to increase shareholder value.

The Strategy

HDL formulated a three-year strategy to increase shareholder value by profitably growing its customer base, optimizing capital, and diversifying through strategic transactions. The strategy was based on HDL’s continuing to provide leading value to its current customer base through operational performance and technology that was eighteen to twenty-four months ahead of competitors. By being more efficient and productive than other distributors and retailers could be on their own, HDL would remain an indispensable link between music suppliers and mass merchants. HDL would also offer a value proposition of providing flexible solutions to customers that would increase its share of current customers’ business, enable it to capture and serve a greater number of retailers, and expand internationally. Strategic transactions would enable HDL to leverage its core competencies of category management and distribution into other product lines and markets.

The Strategy Map

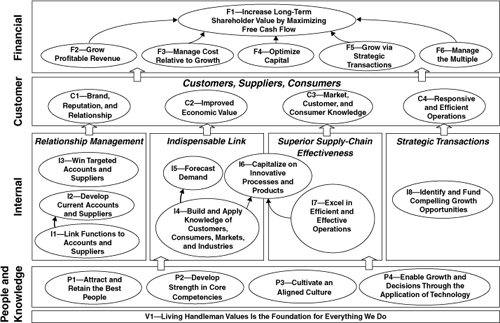

HDL identified twenty-three key strategic objectives across the four perspectives of its corporate strategy map (see Figure 4-8):

Financial Perspective

F1: Increase long-term shareholder value by maximizing free cash flow was HDL’s ultimate financial objective. This objective was motivated by external research that indicated a high correlation between free cash flow and stock price appreciation. HDL identified five financial sub-objectives expected to drive improvements in free cash flow.

F2: Grow profitable revenue. A primary driver of HDL’s strategy was to generate growth in its current business. This objective signaled that HDL should seek revenue increases only when they would enhance profitability.

F3: Manage cost relative to growth. HDL would reduce selling, general, and administrative expenses as a percentage of revenue so that operating profits would increase as revenues increased.

F4: Optimize capital. HDL needed to manage its physical and financial capital effectively so that revenue and profit growth would also lead to shareholder value growth. By using assets wisely and balancing the mix between debt and equity, HDL would increase shareholder value.

F5: Grow via strategic transactions. HDL did not believe it could reach its objectives purely through internal growth with current businesses. HDL also needed to acquire or create new strategic partnerships that align with its core competencies of category management and distribution.

F6: Manage the multiple. HDL would increase its price earnings multiple by clearly communicating its strategy to analysts and investors, executing its financial and operating strategy effectively, and attracting and retaining prestigious customers.

Figure 4-8 Handleman Corporate Strategy Map

Customer Perspective

HDL would achieve its financial objectives by providing its retailer customers, suppliers, and end-use consumers with four key value propositions.

C1: Brand, reputation, and relationship. HDL’s expertise at category management and its reputation for quality would create differentiation from competitors.

C2: Improved economic value. HDL’s relationships and capabilities would produce better operating performance for its retailer customers than they could produce by themselves.

C3: Market, customer, and consumer knowledge. HDL’s superior knowledge of markets and consumers would enable HDL to drive improved sales and profits for its customers.

C4: Responsive and efficient operations. HDL would satisfy customer objectives by being responsive to their needs and making the management of a complex business simple for them.

Internal Perspective

To deliver the four key value propositions in the customer perspective, HDL identified eight strategic objectives across four key internal process themes:

Relationship Management Theme

I1: Link functions to accounts and suppliers. To develop HDL’s accounts with customers and suppliers, HDL would link its internal functions to all areas of customers’ and suppliers’ organizations. The linkages would also contribute to the second internal objective in this theme.

I2: Develop current accounts and suppliers. HDL would maximize sales for its current customers and suppliers by identifying growth opportunities.

I3: Win targeted accounts and suppliers. HDL would also develop its businesses and business models to win new customers and suppliers.

Indispensable Link Theme

I4: Build and apply knowledge of customers, consumers, markets, and industries. HDL would continually look to improve its understanding of consumers in order to provide each of its customers’ stores with the best-selling music selections for that store. This capability would enable HDL to achieve another objective in this theme.

I5: Forecast demand. HDL would accurately forecast demand for its products through superior demographic and market knowledge, identification of market opportunities, and forecasting of industry trends and buying practices. Building and applying this knowledge would enable HDL to achieve its next objective.

I6: Capitalize on innovative processes and products. HDL would differentiate itself by creating and using innovative processes and products that competitors could not immediately duplicate.

Superior Supply-Chain Effectiveness Theme

I7: Excel in efficient and effective operations. In order to capitalize on innovative processes and products as well as to deliver continuous customer satisfaction, HDL would excel at core operating processes.

Strategic Transactions Theme

I8: Identify and fund compelling growth opportunities. HDL would work proactively to identify opportunities for strategic transactions, assess them wisely for financial and strategic benefits, and provide funding for the right opportunities.

People and Knowledge Perspective

To achieve the objectives of the prior three perspectives, HDL identified five objectives to equip the organization with the right people, competencies, culture, and technology.

P1: Attract and retain the best people. Employees who are aligned with HDL’s strategy, values, and core competencies would drive the business forward and help secure HDL’s success.

P2: Develop strength in core competencies. HDL would identify the critical core competencies that drive its strategy and then train or recruit employees who represent the highest levels of those core competencies.

P3: Cultivate an aligned culture. HDL’s entire organization would be aligned to implement the strategy. Employees would understand how they contribute to the strategy and take accountability for achieving it.

P4: Enable growth and decisions through the application of technology. HDL’s technology would differentiate it from the competition. HDL would continually look to better apply technology in its infrastructure, systems, and applications to enable growth and better decision making in all aspects of its business.

V1: Living Handleman values is the foundation of everything we do. Exhibiting HDL’s values of honesty and integrity, accountability, continuous learning, and focus on stakeholders would drive the achievement of every other objective in HDL’s strategy.

Anecdotes

After completing the corporate scorecard, HDL cascaded scorecards to its shared services units, subsidiaries, and departments, and created personal scorecards for its employees. Completion of its corporate strategy map provided HDL with the means to communicate strategy throughout the organization to help ensure successful strategy execution.

_______________

Case prepared by Geoff Fenwick, Mike Nagel, Paul Rosenstein, and Dana Goldblatt of Balanced Scorecard Collaborative. Our thanks to Steve Strome, Tom Braum, Rozanne Kokko, Gina Drewek, and their colleagues for sharing the Handleman experience.