C H A P T E R F I F T E E N

NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

APPLYING THE BALANCED SCORECARD to nonprofit organizations has been one of the most gratifying extensions of the original concept. These organizations strive to deliver mission outcomes, not superior financial performance. So even more than for-profit companies, these organizations need a comprehensive system of nonfinancial and financial measures to motivate and evaluate their performance.

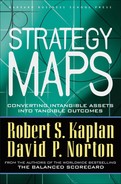

The Boston Lyric Opera (BLO) strategy map demonstrates how organizational performance can be measured even when the output is as intangible as beautiful music and an aesthetic experience. The BLO adopted the Balanced Scorecard after a period of rapid growth and success so that it could have a clear strategy for the future that would be easily understood and supported by its staff, board of directors, and artistic directors. The BLO strategy map represents desired outcomes and performance drivers for its three core constituents—loyal and generous donors, the national and international opera community, and Boston-area residents. The strategy map has led to mission-related initiatives bubbling up from frontline employees, better alignment of management and board processes, and support for a major community opera event in Boston.

Teach for America (TFA) recruits a national teacher corps drawn from talented, highly motivated graduating college seniors who commit two years to teach in urban and rural public schools. TFA developed its strategy map to represent the objectives and drivers for its two core themes for social change by corps members. First, corps members would enhance the educational experience of existing students through their two-year teaching positions. Second, they would influence future and fundamental educational reform through subsequent career decisions and voluntary participation activities. TFA has used its strategy map to engage a new generation of funders in its mission, to align recruiting for its teaching corps, staff, and board members, and to focus more intensively on activities that support alumni initiatives.

BOSTON LYRIC OPERA

Background

The Boston Lyric Opera (BLO) features world-class emerging singers, conductors, directors, and designers. Its mission is to produce high-quality professional opera productions, develop future opera talent, and promote opera appreciation through educational and community outreach. This three-pronged mission statement was enough to sustain the BLO through its early growth. Between 1995 and 2000, subscribers more than doubled, and the number of performances increased by 50 percent, making it the fastest-growing opera company in North America.

The Situation

In 2000, the company faced the challenge of what it should become. Even with the higher audience base, revenues from ticket sales remained less than 40 percent of operating expenses. The BLO needed to convert more subscribers to donors and attract significant funding from its supporters. A key board member felt that the BLO’s kitchen cabinet-style governance structure was no longer sufficient and that a formal strategic planning process was essential to grow to the next stage. An active participant in several arts organizations, this board member had seen organizations fail because leaders had not actively involved the board in strategy and planning deliberations.

Janice Del Sesto, general director, formed a project team of senior BLO executives and key board members, to develop an explicit strategy that could be described with a Balanced Scorecard strategy map. The team included the board chairman, the chairman of the planning committee, and senior administrative staff, including Del Sesto and deputy general director Sue Dahling-Sullivan. Ellen Kaplan, a board member with extensive experience implementing the BSC in nonprofit organizations, served as the internal consultant and facilitator.

The Strategy Map

The team organized its strategy map by three high-level strategic themes, each relating to a key customer group (see Figure 15-1):

- Loyal and generous supporters: Ticket sale revenues, even from selling out every performance, covered less than 35 percent of annual expenses. Subscribers who were willing to pay amounts over and above the high ticket prices (opera is the most expensive performing art to produce) were critical for long-term success. The BLO needed extensive, ongoing support from donors, foundations, and the community. Customer objectives for this strategic theme included attracting new donors, increasing support from existing donors, and recruiting new board members who could help the BLO accomplish its strategic objectives.

- National and international opera scene: BLO could not hope to compete with the world’s great opera houses, but wanted to differentiate itself from the many regional companies in North America. The BLO knew that attracting wealthy opera neophytes by offering a steady diet of Mozart, Puccini, and Verdi would not be adequate for meeting other elements of its mission. It wanted to have an impact on the national and international opera scene through artistically interesting and innovative productions.

The customer objectives for this second strategic theme included attracting the best young talent who become future performers with the world’s most prestigious opera companies, and developing a unique BLO style: crisp, simple, and elegant productions of popular, lesser known, and contemporary works.

3. Community: To attract new generations of audiences, the BLO would build support for opera in the greater Boston community and develop opera education programs for children, their families, and their schools.

With the customer objectives defined for the three high-level constituents, the project team could drill down to defining objectives for the three strategic themes. Enhancing customer relationships largely drove customer objectives for loyal and generous supporters, processes in the operational excellence theme largely drove the production of innovative, quality performances that would be recognized nationally and internationally, and innovation or increase brand awareness theme pointed at enhanced education, awareness, and support in the broader Boston-area community. The three strategic themes enabled tight linkages between the internal and customer perspectives on the BLO strategy map.

Learning and growth objectives related to human capital development, organizational alignment, and technology deployment that would enhance the performance of its critical internal processes. And the financial perspective, with objectives for fiscal health and growth planning, anchored the foundation of the BLO strategy map.

Figure 15-1 Boston Lyric Opera Strategy Map

Anecdotes and Results

The BLO project team cascaded the Scorecard down to individual departments within the opera company, including the artistic leaders. The process fostered a unity and integrity of purpose that had not existed before. The board became much more knowledgeable and aware of the three priorities for the opera company, and did not deflect it into marginal initiatives with little chance of payoff along one of the three strategic themes. All the company’s constituents had become aligned and focused on BLO’s strategy.

Jan Del Sesto, general director, wrote the three themes on the top of the whiteboard in the conference room before every staff meeting, saying, “I want our conversations to relate only to activities that support the themes. That way, we will stay focused on our objectives.” Pre-BSC, Del Sesto noted, the company’s fund-raising and subscriber events had few measures of success and little linkage to strategy. Post-BSC, the development office set priorities for its work and positioned its day-to-day activities to focus on “loyal and generous donors.” These departments did not, as in the past, dissipate their scarce resources on programs that would not yield substantial payoffs. Young artistically trained staff understood for the first time how their day-to-day work affected BLO’s business and the accomplishment of the BLO mission. The staff began to focus on initiatives and events that were likely to have the highest impact on organizational objectives. Cross-departmental initiatives arose: One junior staff person designed a new database application that streamlined donor information and increased the success of solicitation activities. The development department began to work more closely with the marketing/box office department on VIP seating and donor education initiatives. Many suggestions emanated from employees. A junior production staffer created a backstage tour for board members and prospective large donors to show how the magic in The Magic Flute was produced. For its community objectives, the company delivered a major new program, “Carmen on the Common,” two evenings of opera performed free to more than 130,000 people in a downtown Boston park in September 2002. For many, this was their first opera experience.

The BSC had become a management tool for setting priorities among initiatives, motivating employees, aligning the board, and soliciting external support for the BLO’s production and community outreach activities.

_______________

Our thanks to the leadership of Janice Mancini Del Sesto (general director), Sue Dahling-Sullivan (deputy general director), and BLO board members Sherif Nada (chairman), Ken Freed (planning committee), and Ellen Kaplan (BSC project consultant).

TEACH FOR AMERICA

Background

Wendy Kopp founded Teach for America (TFA) in 1989, based on her undergraduate honors thesis at Princeton.1 Her vision was to ensure that one day all children in this nation would have the opportunity to attain an excellent education. TFA recruits a national teacher corps drawn from talented, highly motivated graduating college seniors who commit two years to teach in urban and rural public schools. TFA was one of the most successful nonprofit start-ups in recent years. By 2002, more than 8,000 young people had served as corps members, reaching more than one million students in sixteen urban and rural areas.

Strategy

TFA’s strategy was based on an explicit model of social change in which corps members played two roles. First, they would improve the education experience and life experiences of existing students through their two-year teaching positions. Second, they would influence fundamental educational reform throughout their lives through their careers and voluntary participation activities.

Even before developing a Balanced Scorecard, Teach for America had established five key organizational priorities and started to measure performance for each priority. The priorities were:

- Ensure corps members experience real success in closing the achievement gap between their students and students in more privileged areas.

- Foster the leadership of alumni in pursuing the systemic changes needed to realize our vision.

- Ensure our movement is as large and ethnically and racially diverse as possible.

- Develop a sustainable funding base to support our efforts.

- Build a thriving, diverse organization capable of consistently producing outstanding results over time.

Specific initiatives had been launched to drive improved performance for each priority.

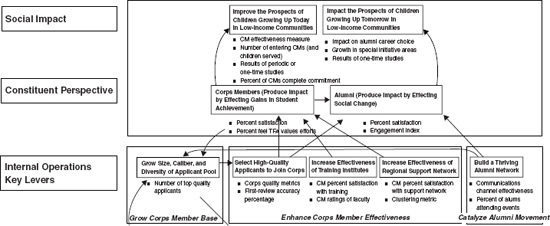

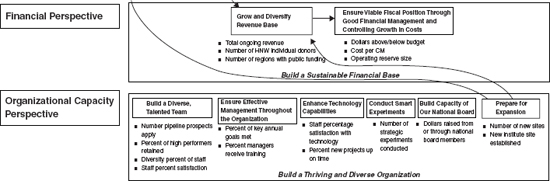

The Strategy Map

With this excellent background in strategy formulation and performance measurement, it was a natural evolution to represent both the priorities and the measures within a strategy map framework. TFA’s senior staff translated its high-level vision, mission, and organizational priorities into a Balanced Score-card strategy map of linked strategic objectives (see Figure 15-2).

The social impact perspective, at the top, explicitly recognized two high-level objectives: improving the educational performance of today’s students, and enhancing the educational opportunities for tomorrow’s students. The first objective was difficult to measure because of the lack of standardized, high-quality metrics in the myriad of schools, regions, subject areas, and grades taught by corps members. TFA chose to use a subjective metric based on staff members “knowing it when they see it.” TFA staff, in end-of-year one-on-one meetings, would ask corps members where their students started the year academically, where they finished the year, and how they knew it. Corps members who could supply reasonable evidence of dramatic gains (as defined more specifically by an internal standard) by their students would count toward this metric.

The second high-level objective, to create social change, would use several new metrics:

- Number of alumni (former corps members) in high-impact, visible positions effecting social change

- Number of alumni engaged in special initiatives

- Results of one-time studies

TFA would review annually the career paths of alumni to determine how many were currently engaged in important positions that could effect social change. TFA executives highlighted, in its special initiatives measures, four specific paths in which to encourage alumni: running for public office or working in public policy, entering school or district leadership, being truly outstanding classroom teachers, and publishing pieces about education and low-income communities. The third measure would be based on ad hoc studies such as those done by Surdna and Stanford on the impact of the Teach for America experience on its alumni.

The social impact measures helped further communicate to staff, resource providers, and especially the corps members themselves that success was not confined to their two-year teaching experiences. To achieve TFA’s vision, corps members had to become lifetime agents for educational change and innovation.

TFA organized its internal operations key levers perspective through three strategic themes tied to their existing organizational priorities:

- Grow size and diversity of corps members

- Enhance corps member effectiveness

- Catalyze alumni movement

The organizational capacity perspective contained several typical learning and growth objectives relating to enhancing the talent and diversity of the employee base, deploying enhanced technology, and establishing alignment of employee goals to the strategy. One new objective would focus on building increased capabilities for its national board of directors.

Figure 15-2 Teach for America Strategy Map

Results

Teach for America has used its strategy map and Balanced Scorecard in a variety of settings to help communicate its direction and illuminate future challenges. For instance, at a major meeting of “investors” who had contributed large amounts of money to help it grow, a presentation of the strategy map and Scorecard led to a robust discussion of how to measure the impact of its alumni. That discussion and others led, ultimately, to improving the new measure of alumni impact to which all stakeholders agreed. Another discussion of the strategy map strengthened the focus on a key internal process. Previously, senior leaders had tended to think of and manage the process of placing corps members in school districts as one part of their broader efforts to train and support corps members. After articulating “placement” as a separate key lever, the organization focused high-level energy on doing everything possible to ensure the placement process went smoothly.

Over the past few years, despite a broadly challenging environment of reduced funding and increased scrutiny for nonprofits, Teach for America has continued to thrive. Applications to the corps grew from just under 5,000 in 2001 to 13,800 in 2002 and close to 16,000 in 2003. This has enabled an increase in the size of the incoming corps from just over 900 to close to 1,900 (nearly achieving, one year early, the 2004 target for an incoming corps size of 2,000). The objective to gauge the effectiveness of corps members led them to revamp the training curriculum and to strengthen the regional support network still further. The alumni movement continues to gain traction, such as through the new and widely used Office of Career and Civic Opportunities. While senior executives are cautious, they expect to continue their 30 percent annual growth in fund-raising and hit their 2003 target of close to $28 million in ongoing revenues, up from $12 million in 2000. And the organization has continued to build its capacity for the future by adding to its technology infrastructure, bringing on strong new staff members and acquiring prominent new national board members.

_______________

We appreciate the support of Jerry Hauser, chief operating officer of Teach for America, for sharing the organization’s experience.

NOTES

1. Wendy Kopp, One Day All Children…: The Unlikely Triumph of Teach for America and What I Learned Along the Way (New York: Public Affairs, 2001).