CHAPTER 19

MASTERY OF PURPOSE AND VISION AT WORK

To attempt to climb—to achieve—without a firm objective in life is to attain nothing.

—Mary G. Roebling

KNOWS PURPOSE

If you look at your life as a story, what is the message? At the end of the book, what will we know about you? What will your story have contributed to the world? How is your story unique? Each life begs for a read. Sure, the book has subplots and supporting characters, but what story did you tell about yourself? Can we grasp the essence of who you are and what you stand for? Or is the characterization fuzzy? When we close the book, is the main character the person you want him to be? Or does he require a rewrite? Are you satisfied with the story you told?

Mastery of purpose requires that you know who you are and what you want to do with your life. It is about being guided by a strong personal philosophy that sets your life's direction. It serves as your inner script, fixing on the plot and giving you constant stage directions for living that purpose. Your purpose comes through in each line you speak, each action you take, each decision you make, and each secondary character and subplot that enters the pages of your life. When you're eighty years old and reading your life book, each chapter speaks to your purpose. What it says will either be unintentional or directed. Mastery of purpose requires that it be directed.

When we align our lives with this sense of purpose, we are authentic and happy. When misaligned, we suffer stress and discomfort. Your life purpose requires a set of deliberately chosen values that support your purpose. But purpose is deeper than merely living your values. You can live a code of values, yet not be sure of your purpose. For example, many people live by a set of religious values that espouse caring and concern for others, honesty, integrity, and so forth. These values are definitely worthwhile and provide a great compass for guiding behavior. And surely living your life according to these values is a significant accomplishment. But purpose requires you to live by a set of values for a particular reason or mission. It requires you to direct those values toward something. Purpose is the mission to which you have been called.

Many people who lived lives of deep purpose have made profound contributions to humankind, such as Mother Teresa's mission to serve the poor and suffering, Martin Luther King Jr.'s mission to achieve equality through nonviolent protest, and Christiaan Barnard's mission to save lives by developing successful surgical procedures for heart transplants. Each set upon a path, put their resources, energy and values toward it, and fulfilled a purpose. Yes, we live ordinary lives by comparison. We are ordinary people. Most of us are not sainted nuns, beloved civil rights leaders, or great surgeons. We are Joe, the factory worker; Pete, the computer programmer; Anna, the front line supervisor; Velma, the middle manager; or Jim, the student. How can a discussion of purpose speak to us, and what does it have to do with emotional intelligence?

Each of us has a purpose to which we are uniquely called. Plato first spoke of it in his Myth of Er in The Republic.1 The Romans called it your genius.2 Laurie Beth Jones, in The Path, calls it your mission.3 Your purpose is your reason for being here. Purpose is not about your job or the roles you have in life. Purpose is larger than that, and it transcends roles and jobs. Jobs end, roles change. Purpose does not.4 For example, my purpose is to touch and affirm people so they can reach their highest levels of inspiration. I can attempt to live my purpose in a variety of roles or jobs. I can do that in the corporate world, I can do that as a mom, I can do that as a friend, I can do that as a Girl Scout leader, I can do that as an accountant. Where I am or what role I have is irrelevant. Occasionally role may conflict so greatly with purpose that you will be forced to find another role, but those instances are rare. For example, if my job were executioner at the local penitentiary, I would more than likely struggle and feel conflicted between my role and my purpose. But most people can live their purposes regardless of the role or job they hold.

Consider Hank. Hank is an accountant in the purchasing department of a big company. When I met Hank, he had just taken the Index for Emotional Intelligence, which measures several factors of emotional intelligence, including “knows purpose.” Hank scored himself particularly low on this item. He talked at length about how he felt that his job was empty. He said he felt bored and had little energy to expend toward work. He said he found little meaning in purchasing widgets and preparing contracts. After several discussions, Hank said that what he found to be meaningful in life was helping and teaching others. He wanted others to see that things could be straightforward. He loved to strip away the complicated and make things simple. Work came easy to Hank. He had a knack for understanding things, and he had a gift for explaining things to others. Hank agonized over his discovery. Because Hank realized that what he enjoyed was helping and teaching others, did this mean that he needed to leave his job? After all, his job was purchasing widgets. After a few more discussions, Hank's agony turned to delight. He realized that his job could provide many opportunities to help and teach others, but he kept focusing on the wrong things. Yes, preparing contracts and paperwork was part of his job, but by focusing on the paper, he felt doomed and unsatisfied. Like a kaleidoscope, he shifted the view to human interaction and offered himself as a teacher. As a result, he gave his work a completely different meaning. His purpose, once discovered, consumed his thoughts and his actions. At work, at home, in the community, Hank kept creating opportunities to live his purpose. His values didn't change, but they had a sharper edge. Everything was clearer once he reframed his world. Two years after his discovery, Hank was promoted. Here's what his performance review said:

Hank's technical skills are outstanding. He understands the purchasing process and accurately prepares contracts. However, Hank's willingness to share information and help others less familiar with the process is of particular note. Without asking, Hank has volunteered to help new employees in the department. He has put together a easy-to-read manual for new hires that thoroughly explains the complicated department process for purchasing supplies for the IST lines. In addition, others have commented on Hank's attitude regarding sharing his knowledge. Two department heads wrote memos regarding Hank's willingness to explain the purchasing procedure to their employees. Hank does this willingly, without arrogance and with no expectation of reward.

Purpose is the foundation of emotional intelligence. It gives new light to everything else, including emotional responses to situations. When we understand our purpose, our emotional response is much easier to craft. Think about Hank. Sure, he still may get angry or frustrated, but because he can quickly review his purpose, the seeds of anger or frustration are less likely to take off in a full-blown hijacking. He realizes that if he's hijacked, these emotional reactions will impede his ability to help and teach others. Most of us would not respond well to a teacher who has angry outbursts or constantly shows frustration. Clarity of intention produces a picture of appropriate emotional response. This works for our lives as a whole and it works in our daily situations. If my intention is to be a team player at work, and I must talk to a coworker about something he or she did not give me for a needed task, my intention will serve as the basis of that encounter. As a team player, I'll discuss it in a civil manner. If my intention is to be a team player and I can't come through with something another team member needs, I'll let her know in advance, work with her to come up with alternative actions, and take responsibility for the situation rather than place blame. The congruence between what I say I believe in and what I actually deliver is essential. If you examine the gaps between what you say you believe and what you deliver, you will often find those gaps are a result of emotional response.

Let's say that Joan thinks she is a team player, but she finds that she can't come through on something for the team. As soon as she realizes this, she feels pressure, perhaps embarrassment or even fear. Her voices kick in as well as her assumptions. Her emotions take over her rational thought. If only I had had the information sooner, I could have gotten my portion done on time. (The Blame Voice.) I hate it when people don't come through. (Assumption.) What am I to do now? It's not my fault I have so many other things to do. (The Victim Voice.) I'm not going to say anything because I know the team will be upset with me. (The Hide Voice.)

Joan is hijacked into inaction. She doesn't have her portion of the work done, and she doesn't let the team know in advance. This inaction causes the team to miss the deadline. The team labels Joan a nonteam player. Joan's actions (inactions) are inconsistent with her intention. Throughout this book, we talk about living our intentions. It is the vital link to closing the gaps between inconsistencies in what we believe and how we act. Intentions in everyday situations as described above are one level to examine. The deeper level is how all those everyday situations combine to paint a picture of our purpose. Every action is a brush stroke contributing to the form that takes shape on the canvas. Every color selected determines the final work of art.

Mary Frances Lyons, in Becoming Who You Are, looks at physicians who are living in an industry with sweeping changes and emotionally charged work environments. She provides an example of a physician who was able to separate his emotional reactions from the work for a more purposeful look at his life. He says, “I was a practicing OB/Gyn taking a leading role in the development of a system-sponsored physician network. To put it mildly, I got sucked in to the negative dynamics that always attend any discussions in depth where physicians are concerned. It was making me ineffective until—one day, for no particular reason that I can identify—I realized that all of this contention had nothing to do with me, personally. It was all about the issues and not at all about me. With that insight, I began to take steps back from the fray, listening and offering ideas and working with people, but all from a different, saner perspective. It was a revelation and a relief to get out of the emotional abyss.”5

A schoolteacher said something similar. “When I realized that all the fuss about testing and holding teachers accountable for scores had nothing to do with me personally,” she said, “I completely changed my attitude. Rather than feel defensive and attacked, I began to focus on the real issue—the children. Suddenly, my mind was free to come up with ideas that could raise scores, teach children, and satisfy administrators. The trick was getting back in touch with the real purpose of education and the reason I was called to education in the first place.”6

Mastery of purpose crystallizes our intentions. We can continuously review our intentions by touching this base. Remember playing tag as a child? You knew you would always be safe at home base. Home base is our purpose. We know that when we come from this place, everything is aligned. We feel comfort. We live authentically. The most discontented people I see in the workplace are people who feel trapped or stuck, who feel as though they are selling themselves for a wage. They feel that their values are compromised on a daily basis. Sometimes these people may need to look for other employment to feel aligned, but I also believe that many times people could reframe their thinking about their present situations. They can focus on the values and purpose they can live within the confines of their present job or role, as did Hank in our earlier example.

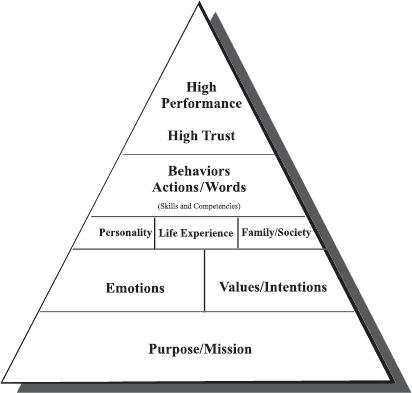

Your self-coach can serve as the guardian angel of your purpose. He can help you align your purpose and take away the conflict between who you are and what others see. He can help you sort through values and other important clues that provide meaning to life. Purpose orders our values. Sure, we derive our purpose by examining which values are most important to us. We also develop our purpose by gaining intimate knowledge about our likes and dislikes, as well as our natural gifts. But once we understand our purpose, it serves as the ordering force. Decision-making is easier because we have the compass read that shows us true north. This compass also helps us understand the emotions that will promote our purpose, as well as those that will detract from it. Therefore, it helps us to know which emotions will serve us so we can turn up the volume on those. For others, we will know to turn the volume down. Purpose adds a deeper meaning to all that we've discussed thus far. Purpose is the base of the triangle in our model in Figure 19.1.

Purpose also requires that you use your natural gifts and talents. Sometimes negative emotional responses are a result of the frustration that we feel when we are trying to do things outside our natural gifts. For example, if you are naturally mechanically inclined, it's easy and fun to fiddle with the broken vacuum cleaner. However, if you have no gift for things mechanical, chances are you would find the task frustrating. Sure, you can learn it, and many of us perform tasks every day that are outside our natural gifts, but if you constantly work to your weaknesses instead of your strengths, you are likely to be less happy and more prone to hijacking.

In The Pursuit of Happiness, David Myers talks about “flow.” Flow, as applied to work, is a term created by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. It means we are in an optimal state of work, where our challenge and our available time and skill are perfectly aligned. If we are called upon to do things that are outside our skill, we will feel stress. If we are not using skills we have, we are bored.7 By uncovering purpose, we must assess our natural gifts, talents and skills and work to match these with available challenges. By definition, our potential for emotional hijackings will wane because we will be more satisfied. But why work at all? Wouldn't we all be happier without work? Not according to Myers. He says in his book that meaningful work is one of the ingredients to a fulfilled and happy life. When Robert Weiss, a research professor at the University of Massachusetts, asked people in a survey whether or not they would work if they had inherited enough money to live comfortably, eight out of ten people said yes.8 When Fortune magazine asked scores of managers, from CEOs to warehouse supervisors, why they worked, the three most common reasons cited besides paying the mortgage were to make the world a better place, to help themselves and others on their team grow spiritually and intellectually, and lastly, to perfect their technical skills.9 The Financial Times also reported that regardless of employees’ interests in lifestyle and income, one thing employees have in common is they want interesting, involving jobs.10 Purpose rather than income is apparently driving actions in the workplace.

FIGURE 19.1

Discovering purpose is not for the faint of heart. It's hard work. It takes lots of pondering and an ability to put together all the pieces of our lives. Skills, knowledge, gifts, values, resources, likes, and dislikes all offer clues about our purpose. True discovery, however, is another matter. It requires deep reflection and reevaluation of all that we are. It also requires sacrifice. But the payoff is profound.

One of my favorite examples is Wally Cromwell. Wally was a corporate attorney with a six-figure income and a young family to support. However, a muse that lived deep inside tormented Wally. He found corporate law boring. Very boring. Wally thrived on making people laugh. He had been doing it since grade school. Yet, he went into corporate law because it paid well and, besides, his dad was a corporate attorney. He could live his life as a corporate attorney and make people laugh in his spare time, or he could radically reorder his life. Wally chose to radically reorder his life. He wrote his mission statement, which was, “To make people's hearts as light as a feather.” He kept his day job for a while, but slowly he began to gain experience and credentials that were aimed at his passion: laughter. He literally went to clown school. Yes, really. He started practicing various routines on family and friends. He volunteered at events as a comic. He made public appearances at local hospitals. He wrote jokes and submitted them to professional comedians. Finally, after two years, Wally quit his job at the law firm. His parents were devastated. His new life consisted of writing comedy for two professional comedians, speaking engagements that left his audience in stitches, professional appearances as a clown, and consulting to teach corporate America to laugh. Three years after Wally left the firm, he was making more than he had been practicing law. But the true reward wasn't in the money. He is aligned and delighted with who he has become.

When it all comes together in one neat package, I think of Jack Roseman. Jack heads the Roseman Institute, serves on a number of boards, and spurs entrepreneurs at Carnegie Mellon University. Jack is a living example of a person connected to his purpose and strongly living his core values. What led me to his door was his reputation as a man who goes out of his way to help others, his outstanding reputation as a leader, and his success as a serial entrepreneur. Shortly into our interview, he paused and said, “Look, there are a few things you need to know about me.” He listed a few facts for me such as: he had a very serious heart attack many years ago that left only half his heart functioning; he grew up dirt poor; he had family members killed in the concentration camps; he had been raised by a mother who was consumed by the fear that her son, daughter-in-law, grandchildren, and siblings in Ukraine would perish during World War II; and he left home at eighteen to make his way in the world with a few parting words of wisdom from his father. (I thought to myself, I've interviewed people with similar backgrounds, but they don't always end up as successful as Jack—what's different about Jack?) His father's parting message was, “Always act as a gentleman.” These words, spoken decades ago, called Jack to develop a sense of values that his father would be proud of. “Fifty percent plus more” is Jack's motto for the way in which he lives his life. He believes that it is his obligation and his privilege to meet people more than half way in his encounters. He brings his sense of values to everything he touches. He lives his purpose daily in the business world and makes a difference in his own life and in the lives of many others. What's different about Jack? Jack refers to himself as one of the “Privileged Poor,” as described by A. Singer.11 The privileged poor have inherited a sense of values and worth far more valuable than money. His worldview enables his success. He doesn't sit around feeling miserable about his childhood; instead, he demands more of himself (fifty percent plus more); and the success (and money) follows.

What does this look like to others? These Workplace Letters shed light on the power of purpose in the workplace.

LETTER #1

Dear Sid,

I've worked as your peer for many years. I believe you have taught me more about life and work than anyone else I've known. You taught me to live my word. There has never been a time when you didn't speak and act the truth. There is no inconsistency between what comes out of your mouth and how you act. You are the most authentic person I have ever met. Through the years, we've all seen examples when others have taken the easy way out. They say to your face one thing because it is easy, but do something opposite. You don't do that. Remember the time when the general manager polled the staff individually when he asked if we were in agreement with his decision? All of us outside the meeting were saying that we disagreed; yet, you were the only one who had the courage to say no in the meeting. I thought your career was doomed that day, but instead, the GM had more respect for you than the rest of us. Your courage taught me an important lesson. You are human and you didn't always come through on things, but you told us when you would be falling short. You didn't blame anyone; you just let us know. Again, you don't pretend. You somehow have managed to figure out that you don't have to play games. We get caught up in the games. We try to outdo one another. You try to outdo yourself. What a difference. Thank you for all these years and the wonderful lessons you've taught me.

With Gratitude,

Geoff

(One employee's true sentiments are expressed in the following letter. He realizes, of course, that it would be inappropriate to send this letter, but it illustrates the importance of aligning purpose with actions.)

LETTER #2

Dear Boss,

You're a fraud. I heard you in a meeting the other day talk about how you believe in treating people with respect. You said that your most important value was how you treated others. You said that nothing was more important to you than the aura you create when you are in the presence of others. You said it so eloquently; you said that you want that aura to be one of dignity, caring, and respect.

Hello? Who are you kidding? Obviously yourself. Let's get down to some examples:

- Last week you told Beverly that she was “dimwitted” because she couldn't find the answer to a problem. (That was your word, not mine.)

- You told Corey that he couldn't have Friday off even though he is getting married on Saturday.

- You said in a staff meeting that our biggest customer was a “pain in the butt.”

- You passed me in the hall the day after I came back from burying my mother and the first thing you asked was whether I had time to run the proof today.

I'd suggest you either keep your mouth shut about what you say you believe in or start aligning your words and actions with what you say. I'd have more respect for you if you at least admitted that you didn't care about people.

Sincerely,

Kim

Some Suggestions for Improving EQ in the Area of Mastery of Purpose and Vision

- Think about times when you are truly your best and happiest. What defines these times?

- Think about times when you feel compromised. What defines these times?

- Take an inventory of the things in life that you feel passionate about. How many of these things are things you do daily?

- Think about times when you are most energized. What defines these times?

- Take steps to rearrange your life based on your life purpose.

- Continually evaluate your life purpose and the actions and activities you are involved in. Are they aligned? Evaluate which actions are closely aligned and which actions are not.

- If you are unsure of your life mission, take a personal inventory of your life and assess your true interests and motivations. This requires hard work and introspection. You may need help from a life coach. The goal of the assessment is to determine your purpose, your calling, and your mission.

- Assess and challenge your values. What do you truly believe in? What beliefs do you hold because others around you expect you to believe them? Find a dear and trusted friend to help sort through your values.

- Think about your present position and your life mission in a new light. Perhaps you are the purchasing manager of a large company and your life mission is to inspire people to treat others in a caring manner. You may find creative ways to live your mission within your present job if you approach it with an open mind.

- Evaluate your actions to determine which ones are closely aligned with your purpose and which ones are removed.

- If your purpose and your occupation are at odds, come up with a plan to align the two.

- When possible, take an assignment based on your interests.

- Do not accept excuses from yourself if you feel you are betraying your purpose.

- Keep a log of lessons learned.

- Check your lessons learned for information about how you can improve your effectiveness in the next situation.

- Make use of your strong points. For example, if you are excellent at organizing, volunteer to organize things.

- Enlist aid when dealing with things that are not your strength. Get coaching, feedback, and assistance to improve.

Exercises for Improving Mastery of Purpose and Vision

EQ EXERCISE #13: YOUR GIFTS

Think about your natural gifts. What skills, knowledge, values, or special attributes do you have that makes you unique? Reflect on your gifts and list them below.

EQ EXERCISE #14: YOUR VALUES CREST

Draw a crest containing the elements that you value most. For example, your crest may have fire to represent passion, a lion to represent great strength, and ears to represent the ability to listen.

EQ EXERCISE #15: A LETTER TO YOUR MOST INSPIRED SELF

Write a letter to your most inspired self. Tell your most inspired self what you see that you admire. Tell your most inspired self what he/she has to bring forth into the world.

TAKES ACTION TOWARD PURPOSE

Can you imagine a symphony conductor without passion for music, a football coach without passion for the game, an artist without passion for his canvas? How do you know that people have passion for what they are doing? Generally, people spend an enormous amount of energy when they care deeply and have committed themselves to something.

The energy and passion that we speak of need not be exuberant enthusiasm. Shouting, cheering, and jumping up and down aren't necessary to show fervor. When we are truly committed to something, quiet passion works just as well. This commitment to our purpose, to something we truly feel called to, is our reason for getting out of bed each morning. In fact, purpose becomes our master. Our workplaces, our homes, our communities, our houses of worship, serve as a backdrop, a setting if you will, where we go to commit and spend energy toward our purpose. Every rote task we perform, every routine detail, every word and action, all serve a purpose. Let's think again about Hank, the purchasing person. He felt bored and viewed his job as mundane when he thought of himself as just another purchasing employee. He saw himself as a guppy in the sea of work, surrounded by massive amounts of paper and perhaps a couple of sharks. Given that vision, his energy level and commitment reflected the hopelessness he felt. However, as he changed his perspective about his gifts and how he could use his workplace as a setting for living his purpose of teaching and helping others, he gained a renewed energy toward work. All of a sudden, work became a place to go to live his mission. All those rote details had new importance. Hank wasn't ever a poor performer, but with this new view, he poured himself into every task, no matter how small, because it supported his vision and purpose. Most of us spend at least a third of our time at work. Just by default, then, work matters. But it matters most when we connect it to something important to us. It becomes more than the pursuit of a paycheck. It doesn't matter if that work is widget making, hamburger slinging, or ditch digging; assuming that it's legal and moral, work can provide a useful outlet for living our purpose.

You must be able to mobilize your energy toward your purpose. When you do that in the workplace, you set an example for your peers and/or your employees. Remember, moods are contagious, and if you are engaged and inspired, others may catch that bug, too. Lots of the apathy and negativity we see in the workplace are because too few people have connected their work with meaning in their lives. That perception and that trend are what you can stop. If you are a leader, not only can you stop it, but you must stop it. The first “baby step” toward breaking that trend is for you to walk through the door each day with your soul and your spirit in hand and a driving passion for what you are doing.

Consider Jim. Jim was a front-line supervisor in a government bureaucracy. This bureaucracy was so well established that it may have been the inventor of bureaucracy. People labored over endless paperwork, much of which seemed useless. They lived in a world of “i”-dotting and “t”-crossing. It was difficult, if not impossible, to make any impact on the people or the system. To top it off, they lived under the constant scrutiny of the media. But for more than thirty years, Jim came to work each day and focused his group on the task at hand. His motto was “making a difference today by doing the best we can.” For thirty years, he kept repeating that motto to himself and to his employees.

He knew what he could change: very little. He also knew, however, that the most positive thing he could do each day was to keep his crew focused on positive contributions and a positive outlook. He was there to support his staff. At his retirement dinner, people inside and outside the organization spoke about how he kept everyone positive. Keeping people positive is a wonderful mission. The world would certainly be a better place if more people adopted Jim's attitude.

In terms of emotional intelligence, keeping focused on our mission and working toward our mission leaves little time for pettiness, which may lead to exaggerated emotional responses. When we focus and expend our energy on things we consider to important, we simply don't get outraged about the little things. Mission gives us perspective. Others see this in us and are amazed at both the energy expended toward goals and the conviction that the goals are right. If we truly know our intentions and care to live them, emotional intelligence becomes all the more important. How else can we influence others toward our purpose except by being aware of and manage our emotional reactions, demonstrating empathy, creating social bonds, collaborating, and resolving conflicts?

One memorable person provided an excellent example of someone living her purpose and living an emotionally intelligent life. Eva, a self employed cleaning contractor, found joy and purpose in sparkling bathrooms. Eva scrubbed for a purpose. Eva rarely missed a call. She would double check each room or office before leaving to make sure things were perfect. When I interviewed her, Eva explained to me that cleaning was one of the most important things in life you can do. “If your house or your office looks like a hell hole and stinks, you stink. You see,” she explained, “when something is clean it sets the stage for everything else. When people walk into a clean bathroom, they walk out feeling more pride, feeling more important, feeling more like they should do a good job, feeling more like they should do perfect work. That is what I do for people and for business.” Eva went to work every day with a tremendous sense of purpose, and the energy she put toward her purpose was remarkable. And so were the bathrooms.

What is exciting for you? If you can't answer that question without much thought, then you probably have some work to do to define your purpose. But if you can answer that question, do you find yourself bouncing out of bed in the morning eager to get to your studio? Are you spending energy and taking actions each day toward your purpose? If so, you are on the path to fulfillment.

Perhaps you read this and it all sounds good on paper, but you lament that your reality is different. Perhaps it is. I am well aware of some work situations that would make it difficult if not impossible to live a purpose. If that's the case, you may consider leaving. Sometimes though, what we must leave are our assumptions and work-views, not our jobs. If Eva thought of her job as cleaning toilets, she may not have been able to muster much passion for the job, but her workview allowed her to think differently about her tasks. What assumptions do you have that are holding you back from putting energy toward your passions? Your self-coach can guide you through those assumptions and perhaps test or reframe what you believe. Perhaps there are other things holding you back. Once I realized what I wanted to do with my life, it took me five years to change my direction. I lacked the courage to act, weighed down with financial considerations and lifestyle changes that I knew would be a reality if I changed my course of action. My internal voices of self-doubt, famine, and fear erupted in a cacophony. Slowly, I learned to quiet them. I learned to develop new voices of hope and optimism, which served to jar my inertia. If I was afraid to take action and embrace my purpose, it was ridiculous to expect myself to inspire others. Until I took steps toward my purpose, I wasn't fully alive. Knowing your purpose is one thing, but taking action toward that purpose completes the picture. As mentioned, sometimes we are robed of our purpose by our assumptions, our worldviews/workviews, or our voices. Some common “robbers of purpose” include:

Victim Mentality: This worldview and its supporting voices say that we can't take action toward purpose because we are a victim in the scheme of life. Living a purpose would require power, and we have none. As long as we are in this frame of mind, we are rendered impotent in terms of taking action toward our purpose.

The Warrior Shield: Some people go though life looking for a fight. I'm not talking about people who have taken up a cause they believe in and fight for it. I'm talking about people who find a fight in everything that touches their lives. If you say the sky is blue, they are the first to argue that it's not. If you say it's a nice day, again they are the first in line to prove you wrong. Fighting to gain nonessential ground depletes this person's energy to the point where they have nothing left to pursue a purpose.

Waiting for Tomorrow: Sometimes people believe that they will live their purpose tomorrow. Tomorrow, when the kids are grown; tomorrow, when the job duties are done; tomorrow, when time allows. The problem with this assumption is that sometimes tomorrow never comes. Living your purpose is something that requires your attention today. Taking actions today toward your purpose is the path to fulfillment.

Martyrdom: Some people believe that they cannot live their purpose because they must suffer “for you.” They must put all of their interests aside “for you.” They must stay quietly in the background and provide “for you.” Trouble is, these people are harboring resentment and let you know it. This resentment is a powerful force that robs them of their energy. Often, when people live their purpose, they may put others first, but it is done out of love and it is energizing, not depleting.

When you view your life through your purpose, you will have a greater understanding of where to put your energy and resources. Energy is a finite, so the actions you take will be directed and focused rather than a random drain of your resources. You will also discover that when you feel tired, it will be a different kind of tired. You'll be tired but satisfied that you are accomplishing something, contrasted with the tired you can feel from sitting in front of the television day after day. Your emotional energy is directed toward something vital to you. This causes a sense of vitality in you. You will know, too, how to direct your resources. Your monetary donations will have meaning and focus. In Fund Raising Management, Michael Maude writes about self-actualized people and donating money to causes. He describes them as knowing precisely what is important to them, so they focus on issues or problems outside of themselves. He also says they devote their energy to a chosen mission with a passion that is inspirational. Self-actualized people are mission driven, and they thrive on being part of something significant. They are the most generous in terms of giving funds to causes they believe in because they are giving for internal reasons, not external reasons. In this case, it's about taking action with the wallet to support your purpose.

Some Suggestions for Improving EQ in the Area of Action Toward Purpose

- Listen to yourself talk. When do you hear yourself hedging or sounding unsure of your position?

- Listen to yourself talk. When do you hear yourself speaking with conviction?

- What actions do you take with extreme confidence?

- What actions drain you? Make a list of actions that deplete you.

- Think about times when you have taken actions most aligned with who you are.

- Listen to others as they speak. What makes someone sound confident? What makes someone sound unsure or wishy-washy?

- List people you think are arrogant; others that you think are confident. Define the difference.

- Listen as someone speaks with confidence. What feelings do you hear behind their words?

- When you state a point of view, determine first the feelings you have regarding your point. Could you improve your confidence by improving your feelings?

- When you're not sure of your position in something, don't pretend. State that you are not sure and are still contemplating your decision. If you pretend, you not only sound like you lack confidence, but you also risk losing credibility.

- Think about a time when you did not act on something you believed in. How did you feel?

- Think about a time when you took an action on something you believed in. How did you feel?

- Sometimes we are taking actions, but we're not focusing on our progress toward our purpose. Instead, we focus on what we haven't accomplished. Be sure to take time each day to reflect on your progress toward your purpose.

- Show more passion about things that are important to you. Sometimes we're just not showing our energy, so others think we're not committed. You can show your energy in many ways—by doing more, by encouraging others to see value, by constantly focusing on what's been accomplished and why it's important.

- Keep your focus even when things aren't going well. Sometimes we stop taking action because obstacles seem to overcome our power. If it's something you believe in, keep going. Every baby step will help you get there.

- If you feel defeated or are questioning your purpose, develop a cadre of people you can contact for support.

Exercise for Improving Taking Actions Toward Purpose

EQ EXERCISE #16: THREE IMMEDIATE ACTIONS

List three immediate actions that you plan to take to live your purpose. If you are unsure of your purpose, those actions should be aimed at gaining clarity about what is important to you.

1Plato first spoke of it in his Myth of Er in The Republic.

2Hilman, James. The Soul's Code–In Search of Character and Calling. New York: Random House, 1996.

3Jones, Laurie Beth. The Path. New York: Hyperion, 1996.

4Bateson, M.C. Composing a Life. New York: HarperCollins, 1989.

5Lyon, Mary Frances. “Becoming Who You Are.” Physician Executive 24 (November/December 1998): 62.

6Jamison, Laura. Interview regarding purpose and teaching, October, 2003.

7Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

8Dumaine, Brian. “Why Do We Work?” Fortune 130 (December 26, 1994): 196.

9Dumaine, Brian. “Why Do We Work?” Fortune 130 (December 26, 1994): 196.

10Weaver, Jane. “Job Stress, Burnout on the Rise.” Financial Times, September 7, 2003.

11Singer, Amy, and Pascual, Jean Paul, eds. “The Privileged Poor of Ottoman Jerusalem,” Conference papers “Pauvrete et richesse dans le monde musulman méditerraneén,” Aix-en-Provence, France, 2002.