CHAPTER 2

THE MYSTERY OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR

I have striven not to laugh at human actions, not to weep at them, nor to hate them, but to understand them.—Baruch Spinoza

Because behavior has such an important effect on performance, it would be worthwhile to understand the complicated factors leading to human behavior, especially our own. Family and societal values, laws and mores of church and state, personality, group influences, assumptions and beliefs, life experiences, and reinforcement and punishment all drive human behavior. These factors account for the vast differences among people. Some of those differences are easy to recognize, while others are subtler. Personality differences are among those sometimes easily identified. For example, some people are innately aggressive or assertive, while others are more passive. Others are outgoing by nature, while others are more withdrawn. We also understand that people who were raised with certain beliefs or values may apply those beliefs to their adult behavior. Similarly, we may recognize that to live in our society, certain behaviors, such as murder, are more than illegal; they are simply not acceptable and may also be against our values. Other behaviors are not only acceptable, but are also encouraged. Saying “thanks” and “please” and helping others—may be behaviors that you were taught. Parents, extended family, religious leaders, and community all mold our behaviors.

Yet, people sometimes behave differently when influenced by a group. Every teenager's parent wonders what peer pressure his or her child is experiencing when it comes to music, clothes, and behavior on social occasions, such as prom night.

But what do you know about your behavior? Probably a good deal. After all, you've been living with yourself for quite some time. However, no matter what your current knowledge, increasing that knowledge is a worthwhile and lifelong process. Also, what you do with that knowledge may be the difference between a life of mastery and one filled with repeated errors and struggles.

Personality and style have long been recognized as influencing behavior. Many companies have trained leaders and other staff to identify personality- and style-driven behavioral differences. We often teach people to adapt their styles to accommodate those of others. We encourage people to empathize, which is to see the world through the eyes of others. So, we know that the highly analytical person craves facts and figures and that the quick-driver types prefer quick summaries that do not bore them with details. Many in the workplace have studied the Myers–Briggs Personality Type Indicator and know that introverts and extroverts draw their energy from different sources that affect the way they work. Introverts derive energy from being alone and require private time to recharge. Extroverts derive their energy from being around others. Myers–Briggs also tells us that extroverts prefer discussing things with others and that they do their best thinking when engaged with other people. Further, those scoring in either the “thinking” or “feeling” preferences in Myers–Briggs have a different way of processing information.1 Therefore, in addition to the factors mentioned earlier, personality accounts for differences in people's behaviors.

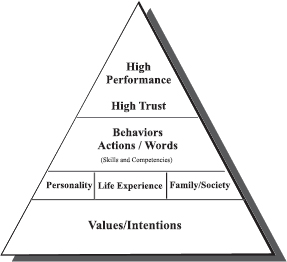

We also understand that values have an impact on workplace behaviors. Most major companies have eloquently written values statements describing themselves as places at which we'd all want to work. Because these values are expected to shape behaviors, they are placed at the base of our triangle model (see Figure 2.1). If you have a well-written values statement, people (both leaders and employees) are supposed to understand how to behave, thereby creating a high-performing culture. Values certainly are an important piece of the puzzle. If people always behaved in the way they should, that would be the end of the story.

FIGURE 2.1

THE DANCE BETWEEN VALUES AND EMOTIONS

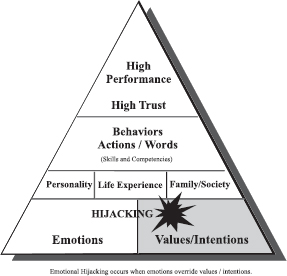

Assuming then that values drive our behavior, how do we explain the following scenario? Let's just say that if you interviewed me, I would tell you that there are two values that I hold dear. (Don't bother to decide if the values are right or wrong, just let the scenario unfold for the purpose of illustration.) First, I do not believe in beating children, and secondly, I do not believe in belittling people at any time—and especially not in public. So, I'm walking down a busy street with my two-year-old grandchild. I do not have him by the hand and suddenly he darts toward the street directly into the path of a Mack truck. I rush to grab him and carry him to safety and then proceed to beat his behind as I scream in the crowded streets, “How could you be so stupid?” Given the values that I stated earlier, could this scenario occur? Sure it could. Why? It could occur because of the tremendous power of the emotion (terror) that I was experiencing as I witnessed my grandchild heading for danger. Thus, our emotions also drive our behavior (see Figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2

However, in this example, my intention was not to belittle or beat the child. In this instance, emotions overrode my values or intentions. When emotion overrides values or intention, it is called emotional hijacking (see Figure 2.3). Everyone has experienced emotional hijacking at some time. Daniel Goleman, who described the term emotional hijacking in Emotional Intelligence, compares emotional hijacking to an emergency signal sent to a part of our brain.2

Although the example was rather extreme and obvious, it's important to recognize that emotions can also play an important, although sometimes more subtle, role in influencing everyday behavior in the workplace. No doubt you've either contributed to or witnessed a hijacking when someone just happens to enter with the wrong message. Who hasn't had the urge to “shoot the messenger?” Some organizational cultures encourage the concept of placing blame and expressing mistrust. In those cultures, hijacking is an expected daily ritual. In one company, employees referred to the room where the morning production meeting was held as “the torture chamber.” At a particular meeting, a review of the numbers proved painful—and that pain was spread to others. I'm referring to the way in which the conversation took place, not the fact that the issue of declining production numbers needed attention. In another company, one executive routinely broke and threw pencils when he was angry or frustrated in a meeting. With each outburst, the room fell into silence. Both of these companies, by the way, had beautifully written values statements that included treating others in a respectful manner. When I interviewed the leaders of the perceived attacks in the torture chamber and the pencil-breaking executive, all said they valued open discussion and didn't want “yes” people working for them. Yet, their actions did not contribute to the type of culture they said they valued. None of them realized the full negative impact of their actions.

FIGURE 2.3

Hijacking takes many different forms. Anger is one of the most obvious to identify. As said earlier, anger in the workplace sometimes takes on a more subtle tone. However, anger is not the only emotion that diverts us from our intentions. Hijacking has many other faces. Most of us have witnessed a time when peers, who moments before a meeting were loudly contesting an issue, are suddenly muted when the powers enter the room. Perhaps we could even count ourselves among those peers who lose their voices when a meeting begins. It is not unusual for people to be muted by some perceived fear of being labeled or sounding stupid. We have placed the mute button on our remote switches because it is perceived to protect us from something threatening. A study of employee silence in the Journal of Management Studies found that most employees who were concerned about an issue did not raise it with a supervisor because they felt uncomfortable speaking to those above them about their concerns.3

Inertia is another one of the more profound manifestations of repeated hijackings. When feeling overwhelmed or fearful, many people take no action at all. They just freeze. Although their intention might be to move the project along or reach some milestone on the pert chart, the emotional glue of inertia has their feet stuck to the ground. People are somehow distracted from their intentions, and they suffer greatly. The project constantly stares them in the face, yet they cannot break the bonds of this powerful adhesive. Over and over, they think about implementing their plans, but are unable to execute them. Whether their inertia is caused by fear of failure, self-imposed standards that are too high, or feeling overwhelmed by the enormity of the task, they are not living their intentions. This pattern of inertia caused by repeated hijackings can become rooted in a person's behavior.

In each of these examples of hijacking—the routine tortures at the production meetings, the pencil-breaking executive, the muting at the meeting when issues were discussed, the inertia resulting from being overwhelmed—all have well entrenched roots that are difficult, but not impossible, to break. Each of these behaviors can be replaced with new behaviors and reactions, but changing requires effort. To break these patterns, new responses need to be created and then repeated, so that new habits can be formed.

HIJACKING CAN ALTER PERCEPTION

It's also important to understand that emotions can alter perceptions. Hijacking can cause you to confuse the facts, as illustrated in the following example. When my daughter was just three months old, we were involved in a horrific automobile accident that resulted in serious injuries and fatalities. A drunken driver struck us broadside on a beautiful sunny afternoon. Our car turned on its side trapping my daughter and me. As I became oriented, I found my daughter dangling in her car seat in the back seat of our twisted automobile. (Yes, thank God for car seats.) I reached for her and was struggling to release the clasp on the car seat when two things became apparent to me. One, I smelled gasoline, and two, I heard people outside screaming, “Get them out of there, it's going to blow.” I finally freed my daughter from the constraints of her car seat and passed her safely to the arms of a brave Good Samaritan. After being helped out of the vehicle, someone handed my daughter back to me. I remember vividly walking along the side of the road to flee the threat of fire. I panicked as I looked down the side of the road and realized that I was walking along a drop off that must have been at least twenty-feet deep. All I could think was that we survived the crash only to be killed by a fall over this deep cliff.

A week after the crash, I went back to visit the scene of the accident. To my surprise, the twenty-foot cliff was no greater than two feet. That's right. I drastically overestimated the depth. My rational brain was rendered completely nonfunctional, as my emotional reaction to the accident distorted my perception and my ability to assess facts. In fact, I would have sworn in a court of law that that drop off was twenty feet or close to it, not two. This example shows how impaired perceptions caused by emotions affect decision-making. Emotions can likewise impair decision-making in the workplace, which can also have serious consequences.

1Myers, Isabell, and Briggs, Katharine. Myers–Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press, 1993.

2Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence., New York: Bantam Books, 1995.

3Milliken, Frances J.; Morrison, Elizabeth W.; Hewlin, Patricia F. “An Exploratory Study of Employee Silence: Issues That Employees Don't Communicate Upward and Why.” Journal of Management Studies 40 (September 2003): 24.