CHAPTER 1

THE CONNECTION AMONG BEHAVIOR, FEELINGS, AND PERFORMANCE

Koppers Building

Conference Center, 9th Floor

Pittsburgh, PA

8:30AM, June 1999

(Group of 10 executives from various companies is seated around a large chestnut conference table. Two flip charts, each divided into three columns, are at opposite sides at the front of the room.)

| ADELE: | Tell me the characteristics of the best boss you have every worked for, the boss that you'd do anything for, assuming that it was legal and moral. What characteristics describe him or her? |

| FRANK: | A man of his word. High integrity. |

| JIM: | Supports me to take risks. |

| HAROLD: | Gives me the credit for the successes. |

| JORGE: | He listened to my ideas. |

| MARTHA: | She challenged me to reach higher. |

| JEFF: | Cares about my development. |

| JANET: | Respectful. |

| KIM: | Open-minded. |

| NILL: | My boss was very authentic. |

| ADELE: | What else? |

| GROUP: | (individually in turn) Easygoing. Genuine. Flexible. Recognized my efforts. Clearly stated expectations. Relentlessly looked for improvements. |

| ADELE: | What else? |

| GROUP: | Innovative. Creative. Self-directed. Inspiring. Compassionate. Sincere. Smart. Visionary. Decisive. Involved. Accessible. Organized. A mentor. |

(Adele moves to the opposite side of the room to the first flip chart.)

| ADELE: | Now, tell me about the characteristics of a bad boss, someone who you wouldn't want to work for. We'll just assume that you've never experienced a bad boss, but perhaps heard about these characteristics through the grapevine. Oh, and no names please. |

| FRANK: | Micromanager. |

| JORGE: | Self-serving. |

| MARTHA: | Poor communicator. |

| JANET: | Unavailable. |

| JORGE: | Judgmental. |

| HAROLD: | Clueless. |

| ADELE: | Wow, I don't need to prime you for this one. |

| GROUP: | Self-centered. Inflexible. Negative. Belittling. Unapproachable. Secretive. Controlling. Insensitive. Temperamental. Irresponsible. Opinionated. Demanding. |

| ADELE: | Anything else? |

| GROUP: | Untrustworthy. Indecisive. Risk-adverse. Blaming. Dishonest. Demeaning. Poor planner. Wishy-washy. |

(Adele walks to the second flipchart and directs the group's attention to Column 2.)

| ADELE: | Now, tell me how you feel when you work for this good boss. That's right I know it's not a word we usually use, but just go with it, please. Imagine it's Monday morning, and you're going to work, and here's what you find when you walk through the door. You find someone who has high integrity, is supportive, gives you credit, shows appreciation, listens, challenges you, is caring, who is easygoing and flexible, and cares about your development, and so on. |

| FRANK: | I feel energized. |

| KIM: | I feel confident. |

| JANET: | I feel empowered. |

| GROUP: | Happy. Appreciated. Trusted. Respected. Loyal. Creative. Competent. Independent. Productive. Motivated. Included. |

| ADELA: | Anything else? |

| GROUP: | Peaceful. Intelligent. Supportive. Supported. Inspired. Committed. Purposeful. Focused. Appreciated. Encouraged. Hopeful. Grateful. |

(Adele walks back the first flip chart.)

| ADELE: | OK, now tell me how you feel when you work for someone who is a micromanager, who is also self-serving, a poor communicator, unavailable, judgmental, clueless, self-centered, inflexible, negative, clueless, unapproachable, secretive, controlling, insensitive, temperamental, irresponsible, opinionated, demanding, untrustworthy, indecisive, risk-adverse, blaming, dishonest, and of course, demeaning. |

| BILL: | Anxious. |

| KIM: | Frustrated. |

| MARTHA: | Trapped. |

| JEFF: | Tired. |

| GROUP: | Sick. Stressed. Demoralized. Angry. Worthless. Stuck. Unproductive. Defensive. Hopeless. Abused. Smothered. Negative. Stagnant. Angry. Depressed. Annoyed. Revengeful. Stupid. Incompetent. Worthless. Sneaky. Indignant. Scared. |

(Staying at this flip chart, Adele points to Column 3.)

| ADELE: | OK, so you're going into work. It's Monday morning, and you are feeling anxious, frustrated, trapped, tired, sick, stressed, demoralized, and angry. Not only on Monday, but you continue to feel worthless, stuck, unproductive, defensive, hopeless, abused, smothered, negative, and stagnant on Tuesday and Wednesday and even Friday afternoon. What does that cause you to do or not do? Try to be specific. |

| FRANK: | Job hunt. (Laughter.) |

| HAROLD: | Call in sick. |

| JEFF: | Go home early. |

| GROUP: | Take as little risk as possible. Cover my tracks with E-mail. Hide in my office. Keep my mouth shut in meetings. Don't offer ideas or opinions. Reciprocate by treating my peers this way. Treat customers poorly. Lash out at others. Look for what others are doing wrong. Be defensive. |

| ADELE: | What else? |

| GROUP: | Save memos. Sabotage. Dump on others. Not concentrate on work. Look for opportunities to prove my boss is a jerk. Isolate myself. As little as possible. |

(Adele walks back to the second flip chart.)

| ADELE: | You're working for a person who is honest and caring, and supportive and gives you credit, shows appreciation, listens, challenges you, is easy going and flexible, and cares about your development. On Monday morning as well as Friday afternoon, you feel encouraged, inspired, empowered, competent, included, and so on. What does that make you want to do or not do? |

| KIM: | Stay with the company. |

| BILL: | Work harder. |

| HAROLD: | Come in early because I want to. |

| FRANK: | Stay late. |

| GROUP: | Look for ways to improve my area. Deliver more. Volunteer. Take risks with ideas. Be creative. Offer ideas and opinions. Treat my staff well. Encourage others to come up with ideas. |

| ADELE: | Anything else? |

| GROUP: | Bring donuts. Speak well about the company on the outside. Recruit others to the company. Display a positive attitude to others. Reciprocate with peers. Treat customers well. |

| ADELE: | Congratulations! You just made the business case for why emotional intelligence is important in the workplace. And a growing body of research confirms what you have just said. |

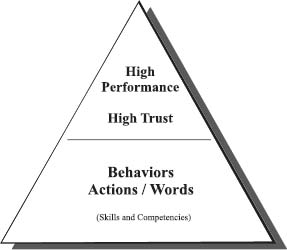

(Adele writes the word high performance in the final column on the good boss chart, high trust in the middle column, and EQ (emotional intelligence) and IQ in the column on the left. See Figure 1.1.)

(Adele walks over to the bad boss chart. She writes the word low performance in the final column, low trust in the middle column, and poor skills and competency in the column on the left. See Figure 1.1.)

What are the lessons from this activity?

LESSON 1

Other People's Behaviors Can Affect Our Feelings.

Recognize that I use the word “can.” Emotional intelligence is the ability to manage ourselves and our relationships with others so that we can live our intentions. Indeed, emotional intelligence is about making choices. However, having said that, it is important to recognize that, other people's behavior can definitely influence your feelings. Just think about the last time someone jumped in front of you at the deli counter or cut you off on the freeway. Those behaviors could have caused you anything from mild irritation to road rage. Or think about the last time at work that people expressed gratitude for your efforts. More than likely, those behaviors had some positive effect on your feelings, causing you to feel happy or proud. Granted the result may vary greatly depending on many things, including the person, the circumstances, and even the mood you're in. In fact, research has confirmed that emotions are contagious. In “The Ripple Effect,” Sigal Barsade states that both outside observers’ and participants’ self-reports of mood were affected by the moods of others.1 In that study, a trained person enacting positive mood conditions was able to affect others so much that they experienced improved cooperation, decreased conflict, and increased perceived task performance.

FIGURE 1.1

LESSON 2

Our Feelings Can Influence Our Performance.

Here again, recognize the word “can.” As we saw in the discussion, emotions can affect performance. In fact, if you think about your own energy and motivation level, you'll recognize that whether at home or at work certain moods often dictate your pace, enthusiasm, and interactions with others. Nothing motivates me to clean the house or cook quite as much as the anticipated arrival of a welcome guest. What may have seemed like a chore in one state of mind suddenly becomes fun in another. The same holds true at work. If I'm feeling overwhelmed or defeated, a simple task may seem insurmountable. When my mood is lighter, I can breeze through the same task and even much more difficult ones without even noticing.

Take the emotion of anger. When feeling angry, you may quicken your pace. All of a sudden you experience an enormous energy boost fueled by your rage. So if we want to boost productivity, perhaps the answer lies in finding a way to keep people in a constant state of anger. Well, maybe not. The problems created by that strategy far outweigh the benefits. It's hard to predict just where that energy is going to manifest itself. The actions that result from anger could be higher productivity as the person works faster and with more determination, or they could be harassment, corporate sabotage, and workplace violence.2 In reality, productivity suffers. Hendrie Weisinger in “Anger at Work: How Large Is the Problem?” states that “Anger in the workplace is the unseen source of many of the productivity problems that confront U.S. business today.”3

Now think about depression. By mere definition, depression slows down one's actions. Motivation levels decrease so that the severely depressed person is unable to function well enough to accomplish daily chores. Even basic grooming becomes an insurmountable task. Imagine that depressed individual in the workplace with stacks of reports to run, lab tests to perform, or transactions to complete. In fact, a study reported in the American Journal of Psychiatry confirms that the likelihood of decreased performance on the job is seven times higher for depressed employees.4 Another study, by AdvancePCS, revealed that U.S. workers with depressive disorders are nonproductive 14 percent of a standard hour workweek.5

Recognizing that some emotions do translate into action and others into inaction is an important foundation to understanding how emotions can be channeled in the workplace. The examples of anger turning to violence or depression rendering one incapable of simple tasks were illustrations to punctuate the point that emotion can cause action or inaction. Clearly, this book does not intend to provide answers to the problems of workplace violence or depression. Those serious issues require a more serious venue. But the vast majority of people can benefit from a general understanding of the effect of emotions on their abilities to function. Tips and suggestions on how to understand, interpret, and harness your emotional resources are invaluable. Besides, as you become more adept at influencing the emotional reactions you bring to your workplace, the more you can determine how your work will be affected. Each of you has within you the power to influence the emotional environment in your workplace. Why would you want to? For some, the appeal may be for greater productivity or higher quality, which will help to ensure the future. For others, it may be that managing the emotional environment in your workplace simply makes your work life better. You'll feel more like going to work. Let's face it; many of you are going to work because you have to. Why not make that “have to” more pleasant? Besides, understanding emotions will give you a sense of mastery that can increase satisfaction in all areas of your life.

LESSON 3

Performance Can Be Enhanced Through Positive Behaviors.

If we take the first two lessons a step further, we can see that behaviors, especially those of the leader, will have a direct effect on performance. Note the consistency of the findings in the published literature. The Journal of Occupation and Organizational Psychology examined the relationship between loyalty to one's supervisor and work performance. Results indicated that work performance on and beyond the job was directly affected by loyalty to one's supervisor.6 Thus, a supervisor who behaved positively commanded greatly loyalty from employees. In First, Break All the Rules, Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman present twelve core elements that are needed to attract, focus, and keep the most talented employees. All of the items point to positive feelings in the workplace that are directly attributable to the relationship with one's supervisor.7 In addition, a survey by Personnel Decisions International reported in HR Focus, states that 37.3 percent of employees believe that interpersonal relationships are of high importance when deciding what makes a good boss. In addition, 19 percent of respondents cited the ability to understand employees’ needs as one of the most important characteristics of a boss.8 Nation's Business reports in “How to Be a Great Boss” that when people feel good about the person they report to, they feel better about the company they work for—and everyone benefits.9 Stan Beecham and Michael Grant in an article in Supervision write that the employee sees the company through the lens of the relationship he or she has with the supervisor. They further state that employees do not leave companies—they leave bosses.10 Organizational Science reports that worker productivity increases because of a supportive social context defined as more support from supervisors and coworkers.11

LESSON 4

Emotional Intelligence Is Important, But It's by No Means the Only Factor That Leads to High Performance.

Intellect has proven invaluable to our success in business. Financial decisions based on analyzing details, sound strategies based on facts and data, and processes and procedures based on review and analysis are all critically important. Businesses could not survive without very smart people to run them. Engineering advancements, process improvements, automation, and supply-chain enhancements can create enormous wealth for company owners and shareholders, and smart bosses are always part of the mix. We are in no way insinuating that emotional intelligence is the only avenue of success; rather, we prefer to think about blending our knowledge and emotional intelligence so that our businesses or organizations can achieve the highest level of success. In fact, given the quality and productivity advances that have been made, it's more and more difficult to get big wins just from improving engineering efforts. However, in many ways, advances in emotional intelligence provide new borders that have yet to be expanded. Our gains in this area can be great.

FIGURE 1.2

With these lessons in mind, a prudent business decision would be to learn more about emotional intelligence and how it can help our business succeed. We can achieve this goal with a model in the shape of a triangle. Because we can safely assume that the output generated on the good boss chart is desirable, I placed high performance at the top of the triangle, supported by high trust. We place behaviors at the bottom of the triangle, because our opening discussion shows that high performance and high trust often grow out of the behaviors of the leader. These behaviors are sometimes referred to as skills or competencies. Therefore, the model begins to take shape, as shown in Figure 1.2.

1Barsade, Sigal G. “The Ripple Effect: Emotional Contagion and Its Influence on Group Behavior.” Administrative Science Quarterly 47 (December 2002):, 644.

2McShulskis, Elaine. “Workplace Anger: A Growing Problem.” HR Magazine 41 (December 1996): 16.

3Weisinger, Hendrie. “Anger at Work: How Large Is the Problem?” Executive Edge Newsletter 27 (November 1996): 5.

4Martin, Melissa. “Depressed Employees Take Twice as Many Sick Days.” Occupational Hazards 63 (July 2001): 16.

5——— AdvancePCS. “Study Finds U.S. Workers with Depressive Disorders Cost Employers $44 Billion in Lost Productive Time.” Insurance Advocate 114 (July 7, 2003): 30.

6Zhen Xiong, Tsui; Farh, Anne S.; Jiing-Lih Chen. “Loyalty to Supervisor vs. Organizational Commitment: Relationships to Employee Performance.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 75 (September 2002): 339.

7Buckingham, Marcus, and Coffman, Curt. First, Break All the Rules. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

8——— “What Makes a Good Boss?” HR Focus 77 (March 2000): 10.

9Maynard, R. “How to Be a Great Boss.” Nation's Business79 (December 1991): 44.

10Beecham, Stan, and Grant, Michael, “Smart Leadership in Tough Times.” Supervision 64 (June 2003): 3.

11Staw, Barry M.; Sutton, Robert I; and Pelled, Lisa H. “Employee Positive Emotion and Favorable Outcomes at the Workplace.” Organization Science—A Journal of the Institute of Management Sciences. 5 (February 1994): 51.