1.5. DEFINITIONS OF CULTURE

In one of the first modern definitions of culture, E.B. Tylor (1877) defined it as "that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, customs, and any capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society."[] A century later, anthropologist Victor Barnouw wrote in Culture and Personality that "A culture is a way of life of a group of people, the configuration of all of the more or less stereotyped patterns of learned behavior, which are handed down from one generation to the next through the means of language and imitation."

In cataloging more than 150 definitions of culture, A.L. Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn provided this comprehensive definition: "Culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit of and for behavior acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievement of human groups, including their embodiment in artifacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values; culture systems may, on the other hand, be considered as products of action, on the other as conditioning elements of further action."[]

Other definitions they catalogued in their work include: Culture is the ways humans solve problems of adapting to the environment or living together; culture is social heritage, or tradition, that is passed on to future generations; and culture is ideas, values, or rules for living.

"Culture," says Geert Hofstede, "is learned, not inherited." Hofstede defined culture as the "collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one category of people from another."[] His landmark research on cultural difference across nations was designed to help identify the major differences in thinking, feeling, and acting of people around the globe. Realizing that we all have what he calls "software of the mind," Hofstede sought to understand more fully the impact of that programming as we interact in the world and in organizations, and to make cultural difference discussable.

In addressing culture and cultural difference, it's important, says Hofstede, to distinguish between human nature on one side, and an individual's personality on the other. His model is shown in Three Levels of Uniqueness.

Human nature is what all human beings have in common, writes Hofstede. "It represents the universal level in one's mental software." Our human ability to feel emotions such as fear, anger, and love and the need to associate with others—these all belong to this level of mental programming. However, "What one does with these feelings, how one expresses fear, joy, observations, and so on, is modified by culture," Hofstede reminds us.

On the other hand, the personality of an individual is his or her unique personal set of mental programs he or she does not share with any other human being.

Between these two is culture, which is specific to a group and is learned, not inherited. Each of these levels of uniqueness has an impact on individuals and groups in the workplace; for our purposes, we will focus on culture—that set of assumptions and cultural traits that each of us brings to the workplace every day—many times unconsciously.

1.5.1. Dominant Culture

We are often unconscious of our own cultural programming. In a September 1999 Harris Interactive poll, only 29 percent of Americans thought having a "unique culture and tradition" best described the United States, while many more felt that way for countries such as China and Japan. We don't see ourselves as having a "culture"; we see others as being cultural creatures.

Members of the prevailing culture in any nation are considered part of the dominant culture, but they often do not know that. They do not think of themselves as part of a "group" because they simply perceive themselves as "normal." But according to Milton J. Bennett, co-director of the Portland, Oregon-based Intercultural Communication Institute, it's necessary to first place yourself in context in your own culture before you'll be able to see other culture clearly.

"The dominant group, whether Han Chinese in China or European-Americans in the United States, tends to neglect their own cultural context," Bennett explains. "We tend not to see our own culture because the dominant group is defined as 'standard.' We don't think we have a culture—that is just the way things are. But the failure to perceive yourself as operating in culture subtly creates the dynamic that you're operating in a standard mode and everyone else is deviant." As interculturalist Edward T. Hall so brilliantly stated it, "Culture hides much more than it reveals and, strangely enough, what it hides, it hides most effectively from its own participants."

When we're operating in a cultural context and actually see ourselves as operating in a specific culture, Bennett notes, then we can begin to see others as variation, not deviation. To understand this issue of dominant culture, we must first create a boundary so there is differentiation between "us" and "them." "We must clarify the boundaries between our culture and the other, as well as generate contrasts between the values and artifacts of our culture and the other," Bennett advises. As Hall observed, the ultimate purpose of the study of culture isn't so much the understanding of foreign cultures as the understanding of our own culture. Complete the "You as a Culturally Diverse Entity" form to get an idea of this concept.

1.5.2. Suggestions for Using "You as a Culturally Diverse Entity"

To identify the sources of one's own cultural programming

To increase awareness about the complexity of each individual's cultural programming and cultural identities, which in turn affect behavior

To raise awareness about the need to find out more about the backgrounds of others in the workplace

To understand that everyone has a culture

Intended Audience

Individuals wanting to increase their understanding and awareness about cultural influences and intercultural interactions on the job

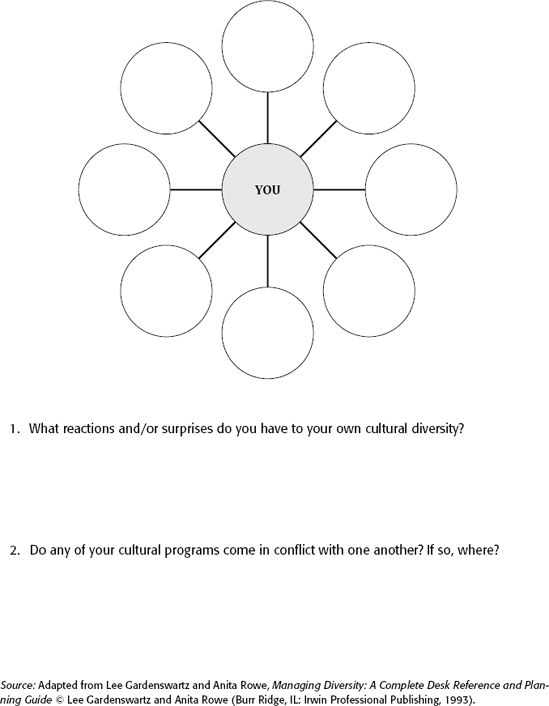

You as a Culturally Diverse EntityDirections: Think about what cultures you belong to (such as Southern, Israeli, women, corporate, mothers). Then think about the beliefs, values, and biases that come from these experiences. What is their impact on you in your professional life? Label each circle with a culture you identify as being part of and next to each write the most important rules, norms, and values you have as part of the group.

|

Trainees in diversity seminars

Members of work teams wanting to understand each other better

Managers wanting to learn more about employees

Members of a global multinational work team, task force, or department

Managers of international or multicultural teams

Time

45 to 60 minutes

Materials

Copies of "You as a Culturally Diverse Entity"

Directions

Ask the group to brainstorm sources of cultural programming and chart responses on an easel or board. Some responses might include family, school, the media.

Ask the group to brainstorm the cultures they belong to. Some responses might include female, marketing, Israeli, Southern.

Individuals write one culture they belong to in each circle on the diagram. Next to each, they write the most important rules, norms, and values they have as part of that group.

Individuals, in small groups or pairs, share information from their circles.

Questions for Discussion/Consideration

What reactions or surprises do you have to your own cultural diversity?

What are some of the cultures you belong to?

Do any of your cultural programs come in conflict with one another? If so, where?

What similarities and differences did you find with your partners/your discussion group?

What do you know about the programming of your colleagues, staff members, and bosses?

What insights did you gain?

How will knowing this information help you work better together?

Cultural Considerations

Talking about cultural identity openly may be uncomfortable for some team members. Tell people at the beginning of the activity that they will be sharing their diagram with another person or a small group. In this way, individuals can control the degree of disclosure.

Caveats, Considerations, and Variations

Rather than ask participants to identify cultures they belong to, ask them to identify sources of cultural programming, which may be individuals such as parents or teachers.

Have members pair or group with those on the team they know least about.

Cultural values and norms are deeply held and almost always implicit and taken for granted, notes Pasi Raatikainen, writing in the Singapore Management Review.[] Their deepest effects on behavior and interaction are usually hidden, says Raatikainen, and extremely difficult to identify and address. Cultural differences inevitably hinder smooth interaction, Raatikainen continues. But because of the nature of culture, say DiStefano and Maznevski, cultural differences also provide the greatest potential for creating value.[] "Culture affects what we notice," they write, "how we construe it, what we decide to do about it, and how we execute our ideas."

As Clifford Geertz noted in his influential book, The Interpretation of Culture, "Men unmodified by the customs of particular places do not in fact exist, have never existed, and most important, could not ... exist." Since culture has such a pervasive influence on us, it's important to understand more clearly exactly what culture is by examining its component parts.

1.5.3. Culture Matters

That icon of Americanism, McDonald's, sells standardized products around the world, yet "localizes" their product to suit cultural differences. For example, they sell "bulgogi" burgers in South Korea and offer teriyaki sauce in Japan and beer in Germany. In the Middle East, Pillsbury puts lamb in its toaster strudels rather than jam; in China it uses pork and dough to make them taste like dim sum.

In building and launching an e-commerce site to sell PCs to consumers in Japan, Dell Computers learned about the impact of culture the hard way—after the fact. Their e-commerce site was built with black borders around it, a sign of negativity in Japanese culture. Other firms have realized that even the icons on their sites must be reviewed for cultural "fit." Mailboxes and shopping cart icons, for example, won't make sense in Europe where people don't take their mail from boxes and don't shop in stores large enough for wheeled carts.

These "accommodations" to local cultural norms address only the tip of the iceberg in terms of cultural difference, literally.

Visible artifacts of a culture—such as food preferences, the size of shopping carts, or the meaning of colors in various countries—are simply superficial signs of the deeper values and norms of a culture. It is to that deeper level of meaning that we must go in order to fully understand cultural difference.

One model often used to describe this dichotomy between what we see on the surface of a culture and the unspoken and unconscious rules of that culture is that of an iceberg, as in the Iceberg Model of Culture.

The iceberg model is a useful way to conceive of culture because it clearly delineates the small proportion of what is visible from the vast piece of culture that is underwater or under the surface. Above the water line are those aspects of culture that are explicit, visible, or taught, such as music, art, food and drink, greetings, dress, manners, rituals, and outward behaviors. Below the water line is "hidden" culture, those things that are implicit in a culture and are often unspoken or unconscious, such as our orientations to the environment, time, action, communication, organization of space, power, individualism, esthetic values, work ethic, beliefs, competitiveness, structure, and ways of thinking.

Culture has also been described as being ordered into three layers by management theorists Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner, like an onion where one layer of peel has to be taken off to see the following layer. In this model, the three layers of culture are explained as:

The outer layer—Artifacts and products such as language and food, architecture and style;

The second inner layer—Norms (the mutual sense of what is right and wrong) and values (the definition of what is good and bad); and

The innermost layer—Basic or core assumptions of what life is and assumptions about how to handle everyday problems.

Historian Patricia Ebrey suggests that if we really want to understand a culture, we should examine the following:

Values—What people say one ought to do or not do. What is considered good and bad, for instance, the importance of honesty or chastity;

Laws—What political authorities have decided people should do and what the sanctions are, for instance, laws about murder or robbery;

Rules—What a society has decided its members should do and the sanctions imposed for not doing it, for instance, social rules about marriage ages, child rearing;

Social categories—Ways of thinking about people as types, for instance, "kings," "friends," "criminals";

Tacit models—Implicit standards and patterns of behavior that a person does not think about, for instance, knowing how to address a police officer rather than friends or knowing how to dress for a job interview as opposed to a dance;

Assumptions—Implicit, not usually articulated ideas and beliefs, for instance, a belief that hard work will be repaid or the belief that things will get better; and

Fundamentals—Categories and ways of thinking that people take for granted and may not be recognized even when pointed out, for instance, thinking in dualities such as good/bad, male/female, beastly/godly or seeing history as circular or as a straight line toward a definite goal.[]

In addition, it is also necessary to look at more formal, and in some cases more visible, aspects of society such as:

Government—The structure of government (monarchy, aristocracy, bureaucracy);

Economic life—How wealth is owned and transferred (through family ties, money), the type of production (farming, industry, services);

Social structure—The class system, gender roles;

Religion—Religious organization, belief systems, clergies;

Literature—Types of literature (oral, written), extent of literacy; and

Art—Place of art in society, methods, purposes.