Variance Analysis

Plan Revision and Scope Management

Project Communication Principles

Learning Objectives for This Chapter

Learning Objectives for This Chapter

Understand variance analysis and apply these concepts in Microsoft Project

Perform root cause analysis for unfavorable variances

Comprehend the project management principles of plan revision and scope management

Understand how to plan, manage, and apply change control principles for project scope changes

Identify project communication principles

Define the elements of a meaningful status report, communications planning considerations, and the concept of the communications management plan

Close a project

14.1 Variance Analysis

Variance analysis is the process of identifying and understanding differences between current progress and the initial baseline estimates for a project work plan. Variance analysis is an important aspect of project control because the process highlights potential trouble spots in an evolving project.

Overview of Variance

Question: How does a large software project get to be one year late?

Answer: One day at a time!

—The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering by Fred Brooks

Types of Variances

Favorable vs. Unfavorable Variances

In project management terms, a variance is the difference between the anticipated state of the project and the actual state at a given point in time. At the beginning of the project, when the planned schedule, budget, scope, and so on have just been calculated, the actual state and the predicted state are exactly the same—that is, there are no variances. This is the point at which the project should be baselined.

As time progresses, the execution of the project may not follow the plan exactly. For example, if a task starts later than it was scheduled to start, there is a difference between the baseline start date and the actual start date for the task. The actual start date is later (a larger number) than the baseline start, so the difference between these two dates is a positive number—that is, there is a positive variance. As this example illustrates, a positive variance is unfavorable. In this case, where a task is late to start, subsequent tasks may also be delayed, and the recalculated schedule may show a finish delay.

All values captured as part of the project baseline information can be compared with the current schedule’s value. You may have variances for work, start, finish, duration, and cost. In each case, a positive variance is unfavorable and means that the current schedule is greater than the baseline value. On the other hand, if tasks are completed earlier than scheduled or with less effort or less money, the corresponding variance would be a negative number and would be regarded as favorable.

The most common work plan variances (work, cost, start, and finish) measure the difference between the current estimate and the original baseline estimate. If tasks are being completed late or in excess of their original work estimates, the project manager should look for trouble signs regularly to be sure that the plan is revised to adjust to the day-to-day realities of the project. If progress is not as expected, the project manager has to figure out how to revise the plan to extend the scheduled finish date, adjust resource assignments, or reduce scope.

The values in the current work, cost, start, finish, and duration fields are usually modified through the tracking process. As team members report unexpected changes in the plan, the current values will diverge from the original baseline values, causing variances.

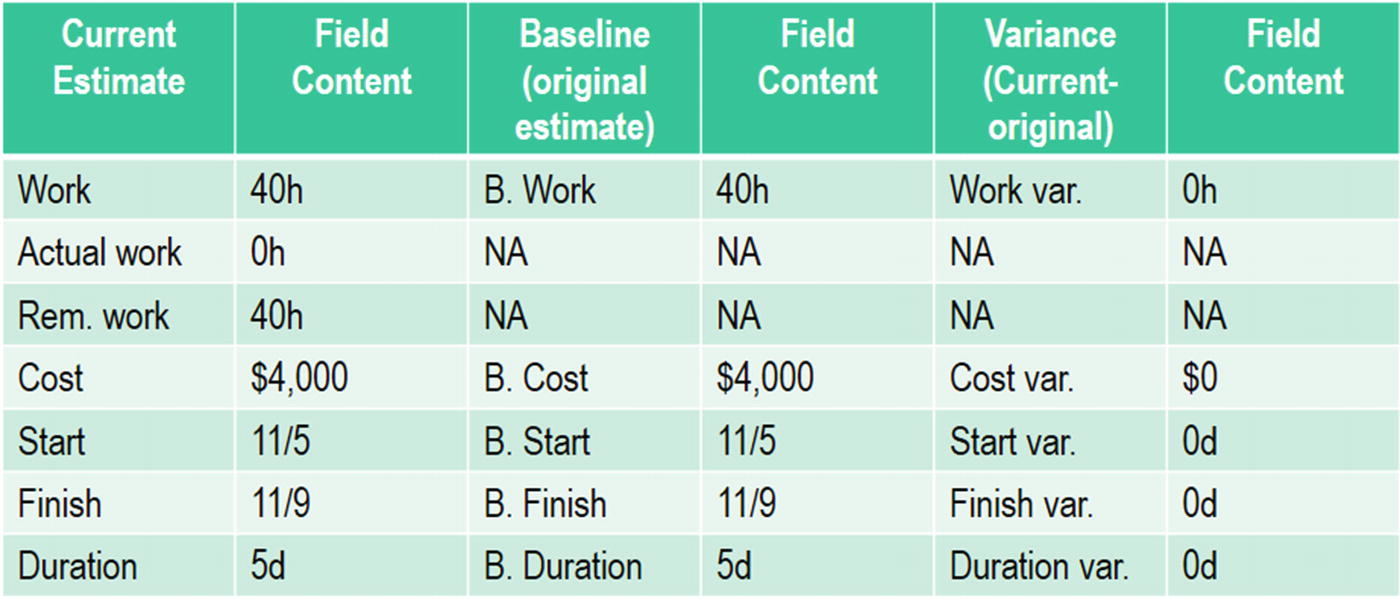

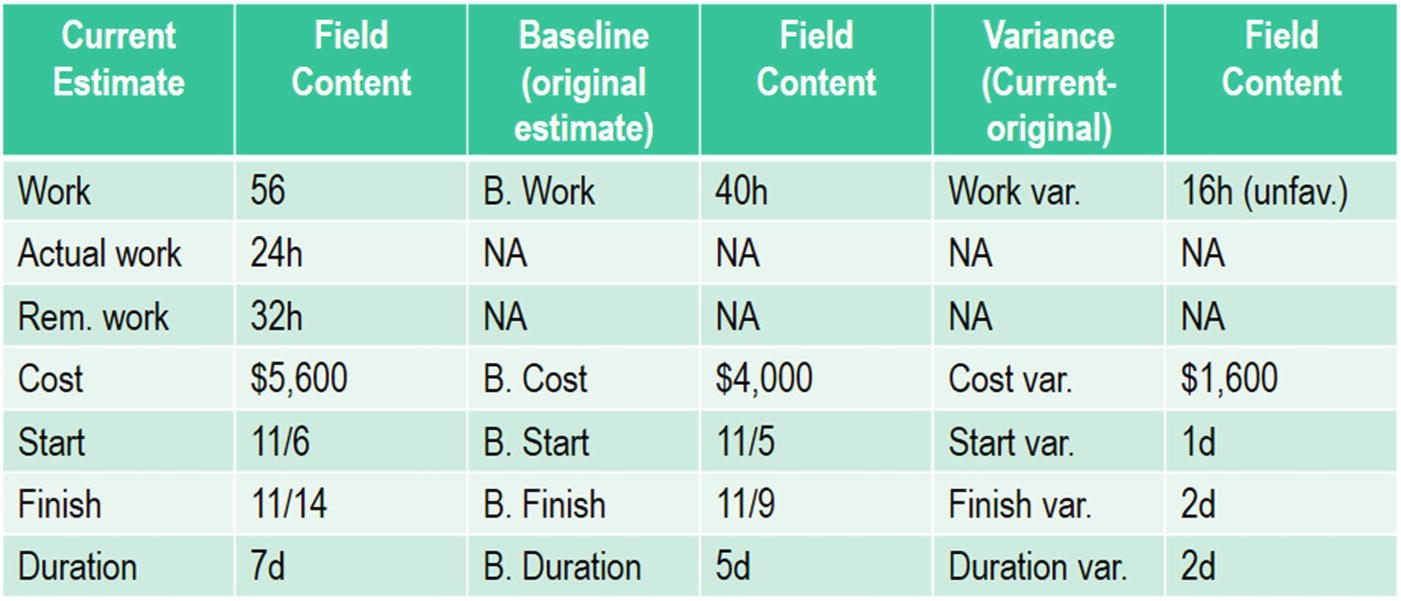

Summary of Variance Types (Using Microsoft Project Field Names)

Instructor Text

Available In | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Variance Name | Calculated As | Task Field? | Phase Field? | Resource Field? |

Work Variance | (Current Work – Baseline Work) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Cost Variance | (Current Cost – Baseline Cost) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Duration Variance | (Current Duration – Baseline Duration) | Yes | Yes | No |

Start Variance | (Current Start – Baseline Start) | Yes | Yes | No |

Finish Variance | (Current Finish – Baseline Finish) | Yes | Yes | No |

It’s important to note that variance calculations in Microsoft Project require baseline data. If there is no baseline, there will be no variance.

Before applying actual progress

After applying actual progress

Interpreting Variances

Those who say they can perform project control without comparing project performance to a baseline do not fully understand the meaning of project control.

—Harvey Levine, Project Management Using Microcomputers

Finding Trouble Spots in the Plan with Variance Analysis

Can the remaining work be performed by the end date?

Do estimates need to be adjusted based on current variance trends?

Are resources arriving as scheduled?

Are schedule bottlenecks preventing tasks from starting and completing as planned?

Which tasks or resources require additional attention to get back on course?

Looking for Trouble

One of the key questions resulting from variance analysis is, “Will the project still finish on time?” One of the key indicators is the total remaining work for the entire project.

Consider this example: There are 10 months left on the project, ten people assigned full time, and 18,000 hours of remaining work; will the project complete on time? One person can comfortably perform about 130 hours in a month, so ten people can perform 1300 hours in a month and 13,000 hours in 10 months. In this example, it looks like the 18,000 remaining hours will not be completed by the target end date.

Date | Project Work Variance |

|---|---|

10/8 | 50 hours |

10/15 | 100 hours |

10/22 | 200 hours |

If the variances are worsening each week, your estimates may need to be adjusted. What happens if resources arrive late? Your work variances may be acceptable, but what will the date variances look like?

Other Considerations

Note the way that start and finish variances are calculated: they use the current estimated date, not the actual date. This means a task that has not started yet can create a variance, but how?

There are two primary ways to make sure your plan remains dynamic and up to date: rescheduling unstarted and late tasks and rescheduling remaining work on in-progress tasks. These rescheduling processes help you avoid stagnant work plans, a common problem for late and overbudget projects.

An Example

Field | Value |

|---|---|

Baseline | 1000 hours |

Actual Work | 500 hours |

Remaining Work | 500 hours |

This project was estimated to be 10 months in duration. It is now 8 months into the project.

What is the estimated vs. actual burn rate?

How many hours of actual work should have been consumed?

How many hours have been consumed?

Based on the current burn rate, what is the estimated total duration of this project at completion?

What would we see if we looked at the start variances for this plan?

The current estimated work for this project is 1000 hours (500 actual plus 500 remaining). The baseline is 1000 hours, so this project is in good shape, right? But the project was supposed to be 10 months in duration and 8 months have already passed. There’s obviously some kind of problem, but we don’t see it by looking at the work variance (which is zero hours).

What’s the Problem?

Assume a constant resource load on this project. If the total baseline work is 1000 hours, how many hours should be used per month on a 10-month project? (100 hours)

How many hours have been consumed to this point? (500 actual hours)

How many hours should have been consumed to this point? (8 months times 100 hours per month is 800 hours)

How many hours are really being consumed per month? (500 hours / 8 months = 62.5 hours per month)

At this rate, how long will this project take to complete? (16 months)

Another Example

The current date is 2/15. Five tasks were scheduled to start on 2/1, but have not.

What is the start variance for these tasks?

What’s the Problem?

If a task does not start when it’s supposed to, it will not create a variance unless it is rescheduled. The task in this example’s baseline start is 2/1, and its current start date is 2/1; therefore, its variance is 0 days.

The task has to be rescheduled before there is a variance. What if the task is rescheduled to 2/20? Now its baseline is 2/1, but its current start date is 2/20. A variance of 19 days will be calculated (assuming all days are working days).

It might be tempting to wait until actuals start arriving for the task, since an actual start date will override the start date (reality always wins), creating a start variance. The problem is, by the time actuals begin to arrive, it may be too late to do anything about the variance. Remember, the sooner you can identify and analyze an unfavorable variance, the greater chance you have to mobilize effort to recover and the more options you have.

14.2 Plan Revision and Scope Management

I come from an environment where if you see a snake, you kill it. At General Motors, if you see a snake, the first thing you do is hire a consultant on snakes.

—H. Ross Perot

Preserving the Integrity of the Plan

Creating and publishing a project plan is only part of a project manager’s duties. Another key function is maintaining the state of a project plan so that it continues to show an accurate picture of the project as time passes. This is where maintenance of the project plan is important. It must reflect not only that time has passed, but also that some work has been done on tasks. It must also account for the fact that there may have been changes in how reality actually turned out compared with what was anticipated when the plan was originally created.

If a project is in trouble, it’s important to remember to use the plan to manage the project—don’t deviate from the plan, change it! Depending on the type of problem you are having, there are different strategies you’ll need to employ to get your plan back on track. The bottom line is that something needs to change in the future if you are required to deliver on time and on budget with high quality and all expectations met.

Tools can help the project manager revise the schedule, but first you have to know what will work for you on this project in your particular situation. Changing the work plan is not as easy as simply changing scope, schedule, or resources. There are usually some pretty limited options; for example, your sponsors don’t want to cut scope, the schedule is not negotiable, and resources (people, machines, and money) are limited. Some project managers fail to recognize the need to adjust one of these factors and end up compromising quality.

Getting Concurrence

A cheaper resource can help the project stay within budget, but the work estimates may increase due to lack of experience of the cheaper resource.

A scope reduction may help, but you are probably sacrificing some of your objectives to stay within schedule and budget.

Adding lead (overlapping tasks) may appear to shorten the schedule but often increases the risk of missing the schedule because of the possible need for rework.

The unfortunate reality is that serious oversights in the SOW or plan will significantly reduce the chances of completing the plan according to all of its original expectations.

Why Plans Should Be Revised

Management must have a purpose and dedication that must have an emotional commitment. It must be built in as a vital part of the personality of anyone who truly is a manager.

—Harold Geneen, IT&T

When can a plan be changed? Minor plan revisions can turn into major revisions that require the project manager to ask for more funding, to redefine the project scope, or to re-baseline the plan.

Stage-limited commitment provides for re-planning at the end of each phase. If this expectation is set properly, the project manager may have the opportunity to make major plan revisions at every major milestone.

Sometimes the project manager has to accept the reality that unfavorable variances are continuing to mount and the trends cannot be reversed. This situation should force a major re-think of the overall project SOW and a new plan to deal with the problems before the project fails completely. Communication is critical at a time like this. The project manager must let management and the sponsors know what’s going on and why.

Variance analysis records should be maintained to provide good documentation for why the plan must be modified.

Aggressive Revision

How can the project manager avoid these problems?

Project plans must be regularly and aggressively revised to keep them in line with current activities. Drastic changes to the plan are often the result of too much time passing between the project control cycles of tracking, analysis, and revision.

Strategies for Plan Recovery

Plan Recovery Using a Tool

Project management tools can help with “what-if” analysis.

Multiple options can be rapidly generated.

Output can be summarized for management presentation.

Data can be extracted to answer very specific questions.

Crashing the Schedule

When the project manager is presented with the need to make drastic changes to achieve the original schedule, project management tools can help investigate strategies quickly.

- Changing the critical path

Adding or breaking links

Adding more tasks to the critical path by including tasks with small amounts of slack

The possibility of displaying multiple critical paths

Adding lead or lag time to tasks

- Decreasing the task duration

Adding resource(s) to effort-driven tasks

Decreasing a resource's work on a task

Reducing scope

Deleting tasks

- Using Risk contingencies

Drawing upon “buckets” or a management contingency line

Assigning overtime work

All these strategies are simply ways to visualize what could be done; actual solutions require stakeholder support and agreement.

The Foundations of Change Control

The project manager has made it clear what the scope is.

A sound approach to change control highlights the importance of the definition document, specifically completion criteria.

Strict scope management also requires adherence to the deliverables acceptance procedure.

Change requestors acknowledge that their request is out of scope.

This second crucial assumption relies on the communication and acceptance of the change control procedure at the start of the project.

Even when these two assumptions are valid, scope management requires a tenacious attitude from the project manager.

Project managers sometimes become overly concerned with client satisfaction when they are asked to make “free” scope changes. Effective project managers manage scope well by knowing how to say “no” with a smile; perhaps more importantly, effective project managers know how to say “Here’s what it will cost, is that OK?” with a smile.

Planning for Change

Anticipate probable changes on the next project. This may mean being more rigorous when developing the work package descriptions or including additional risks in the list.

- Have an explicit change management process. This may include process documents such as

Project Change Request (PCR)

Change Order

Change Authorization

Contract Amendment

Define, plan for, and track project and management reserves with management. These may be represented as a “bucket of hours” or a contingency budget.

With a change management process, it should be clear that a change request is not the only step. There needs to be an impact assessment; approval for any change in schedule, budget, scope, or quality; and a formal update to the plan.

Impact Analysis

When project managers are presented with requests for change, they are usually asked to estimate the impact of making the change. A common set of questions might be: How much will it cost and when can I have it?

Since the project manager can anticipate that changes are inevitable, he/she can also anticipate that requests for impact analysis are inevitable. As a result, the project manager needs to load a task in the plan and allocate hours for “analyzing the impact of change.” For a plan with 2000 hours of project management time, the impact analysis might be allocated 10%, or 200 hours of time.

Each time a request for change is submitted, there will be a budget of hours to perform the impact analysis without adding to the overall cost of the project.

If your project sponsor resists a line item for impact analysis, you might need to inform your sponsor that even impact analyses are out of scope. Yes, you do charge for estimates!

Summary Change Control Procedure

Change request is completed by team member or user and submitted to project manager for evaluation.

Project manager and primary client contact approve change for impact analysis.

Project manager records time spent on analysis and reports impact (price, schedule, scope) and recommendation for approval or disapproval to client.

Out-of-scope changes are recorded and deferred, if possible.

In-scope changes may have to be added to work plan immediately.

In- or out-of-scope changes may be disputed and sent for arbitration in extreme cases.

Approved changes are recorded and signed by project manager and client to indicate approval.

Crossing the Line

This procedure should be adopted early in the definition stages of the project. The expectation that scope will be tightly managed must be set from the beginning.

A good project manager will quickly condition the project team and project sponsors to the idea that scope changes will be tightly managed and will not be implemented without a formal, written procedure.

Introduce it in the SOW.

Review it at the project kick-off.

Devote a section to it on the status report, such as in the following figure.

Example status report with a section on change control

14.3 Project Communication Principles

The Elements of a Meaningful Status Report

Summary

Planned accomplishments for this period

Actual accomplishments for this period

Explanation of differences

Major tasks planned for next period

Issues/concerns/recommendations

- Project work plan trend analysis (often displayed graphically)

Cumulative task summary

Work variances (see Section 14.1, “Variance Analysis,” for a refresher on variances)

Start variances

Finish variances

Week-to-week trends (gaining or losing ground)

Change control summary

Financial summary/cost variances

Project Communications Planning

What information does each stakeholder or group of stakeholders need?

When will they need it?

What’s the best way to communicate it to them and what tools are available?

How and how often should we review the communication plan for effectiveness?

Most project communications planning is done as part of the early project planning phase, since that’s when communication begins to become necessary. It is tempting but dangerous to assume that decisions made in the very early days of the project will remain true and useful as the project matures.

Communications Planning Considerations

Project organization and stakeholder positions

Technical disciplines and departments included in the project

How many people will be involved and where they will be located

External communication (e.g., likelihood of public interest)

Does project success require having frequently updated information constantly available, or would regular written reports do?

Are necessary communication systems already in place, or should implementing those systems be part of the project?

Will project participants require training?

Is the available communications technology in the organization likely to change during the project? How might that affect the project?

Constraints – Constraints in this context are factors that limit the project manager’s options. Are there information security needs or contract provisions that might limit the team’s choices?

Assumptions – Assumptions are factors that must be considered real for planning purposes. Assumptions involve risk, but unrecognized or unstated assumptions greatly increase that risk.

Communications Management Plan

The methods which will be used to collect and store needed information; these should also cover updates and corrections.

A description of what information (status reports, schedule, technical documents, etc.) will flow to whom and what methods (written reports, meetings, etc.) will be used to distribute the information.

A description of each item of information to be distributed, including the format, content, level of detail, and conventions or definitions to be used.

A schedule showing when each type of communication will be produced.

A description of the procedures to be followed to get information between scheduled communications.

A plan for reviewing and updating the communications plan as the project progresses.

As with many of the plans we’ve covered to this point, a communications management plan may be formal or informal, highly detailed or broadly framed, depending on the needs of the project.

Administrative Closure

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge includes administrative closure as part of the project communication process. Administrative closure consists of documenting project results for formal acceptance by the sponsor, client, or customer. It includes collecting project records, ensuring that products meet final specifications, analyzing project success and effectiveness, and archiving such information for future use.

Administrative closure activities should not be delayed until project completion. Each phase of the project should be properly closed to ensure that important and useful information is not lost.

The overall purpose of administrative closure is twofold. One critical issue, of course, is formal acceptance of the project (or phase of the project) by the project client. Some form of documentation that the client or sponsor has accepted the product of the project should be prepared and distributed to management and team members.

The second purpose is to support continuous improvement of the project process within the organization. Being good at what we do is always easier than getting better at what we do. A major way to do that is to have some form of “lessons learned” process beyond the usual terminal project report. The most effective approach is a face-to-face meeting among the project team where team members focus on what they have gotten from the project experience that is worth keeping for their own use and sharing with other members of the organization. This helps overcome the natural resistance to the “report card” approach, which is far more common in organizations.

The real issue isn’t how did I do on the project (because I can’t change that); it’s how will I use this experience on my next project?

End of Chapter Quiz Questions

End of Chapter Quiz Questions

- 1.

What is variance analysis?

- 2.

Fill in the blank: In project management terms, a variance is the difference between the ________ state of the project and the ________ state at a particular point in time.

- 3.

In project management, what are the most common work plan variances and what do they measure?

- 4.

What are the two primary ways to make sure your plan remains dynamic and up to date?

- 5.

True or False: If a task does not start when it is supposed to, it will create a variance when it is not rescheduled.

- 6.

Fill in the blank: The project plan must reflect not only that time has passed, but also that some _________ has been done on tasks.

- 7.

Who usually must approve the revision strategy before the project manager can revise the plan? __________________

- 8.

What are some examples of trade-offs that project managers may be forced to make?

- 9.

What are some of the ways that project management tools can be used as part of the plan recovery strategy?

- 10.

What are some ways a tool can help you visualize the effects of plan revision?

- 11.

What two important assumptions does effective scope management make?

- 12.

Effective project managers manage scope well by knowing how to say what word? Explain.

- 13.

What are some strategies that a project manager can implement to avoid the worst effects of project change and be prepared?

- 14.

What are some ways to manage stakeholder expectations about scope change?

- 15.

How should the project status report be structured?

- 16.

What is the overall purpose of administrative closure?