CHAPTER 6

How Will I Deliver on My Vision and Promises? Part I

From Deal Strategy to Pre-Close Integration Management

If you think you’ve done a lot of work to this point and have made many decisions, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Integration is where the rubber meets the road.

There can be a tendency to race to announcement and treat it like a finish line, but such an attitude can lead to stumbles. Acquirers can be ill prepared for the sheer volume of work that is involved in moving to planning the actual integration. It requires engineering a process that will involve as many as 10,000 non-routine, highly unusual decisions, and senior leaders will have to devote significant time and energy while the rest of the organization swims in fear, uncertainty, and doubt. And remember, investors are smart and vigilant—they will track the results.

In fact, while this chapter comes after chapter 5’s focus on Announcement Day, acquirers have to begin thinking about the topics we address here and in chapter 7 well before they go public with the deal. Knowing how much and where synergies will come from, and the resources required to achieve them, should be central to the approval process for the deal.

Non-routine decisions large and small abound in post-merger integration (PMI) planning. They include how to achieve the deal’s axis of value (growth vs. cost or some combination of the two) along with a new operating model, how the go-forward leadership structure should be created to meet deal objectives, changing leadership and spans of control, implementing new enterprise management systems, whether to merge sales forces, where to base headquarters and what real estate footprint to retain, and specific synergy targets with owners by function and business.

The list includes seemingly trivial issues like summer Friday schedules and which holiday and vacation policies to adopt. Many of those smaller non-routine decisions won’t break the deal, but they will need to be made somewhere. And the longer that decisions go unmade, the more employees will be left wondering and distracted from customer care, product quality, and innovation.

At the same time, acquirers must not run afoul of the anti-trust division of the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the United States or governing bodies in other part of the world (e.g., European Commission in Europe, Ministry of Commerce in China, etc.). The Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) regulations in the United States in short require that both parties in a merger act as two separate companies until they are legally one. Although they can do significant PMI planning, they cannot go to market or operate as if they are one company and cannot share competitively sensitive information that could change the way either party did business if the deal did not proceed. (See the sidebar, “Clean Rooms and Clean Teams.”)

Clean Rooms and Clean Teams

Clean rooms are a construct of data confidentiality that allows sharing and analysis of competitively or commercially sensitive information. Clean teams have privileged access to that information under specific clean room protocols—rules that govern data access, sharing, analysis, and distribution of outputs. Beyond conforming to HSR regulations, clean rooms can relieve anxiety either side might have in sharing data as well as enable maximal use of the planning time between announcement and Day 1.

Clean rooms are essential for several use cases, including accelerating integration planning, making organizational and operating model decisions (e.g., shared services vs. dedicated in-functional support), and identifying and evaluating potential synergies (e.g., overlapping vendor raw material spend, product pricing and supply chain network optimization, customer rationalization, and evaluating cross-selling opportunities).

Clean rooms and clean teams are used for testing hypotheses developed during the diligence phase and, more important, developing specific plans post-signing that will be implemented after Day 1. For example, making an operating model decision on a direct versus a distributor sales force will require knowing customer revenue and profitability, revenue contributions of various markets, and sales force performance metrics.

Clean room analysis starts with separate data requests sent to both deal parties such that commercially sensitive data can be uploaded in a restricted environment with privileged access only to the clean teams. Clean teams are typically staffed with third parties, including consultants and external legal counsel, to ensure that no one with access to sensitive information would be employed by either side if the deal is abandoned. Leaders nearing retirement might also be involved in the process.

Once the analysis is complete, an aggregated output with appropriate masking and anonymization of sensitive information is first reviewed by external legal counsel of both parties and then jointly shared with the relevant integration teams. For example, cross-sell opportunities might be developed using customer-level information, then aggregated at a product or geographical level for sharing with the commercial integration workstream. Detailed data, plans, and initiatives can be declassified and shared with relevant teams for tactical execution after the legal close.

Integration Planning: The Basics

Integration planning provides a short period of time to transfer the deal thesis across parameters of customers, products, technology, go-to-market strategy, and talent into milestones and key performance indicators (KPIs) that are specific and measurable and that will maintain business continuity, deliver on operating commitments, and preserve the momentum of both businesses while providing the blueprints for achieving at least the promised synergies. This is the period when acquirers plan the transition from the current state to the future state where they will deliver new value to customers or operate at a more efficient cost structure than exists at the time of announcement—or both.

Integration planning must accomplish three major goals:

- Maintain the momentum in both businesses (preserve growth values)

- Build the new organization (implement new operating model and organization structure)

- Deliver the promised value (exceed performance implied by the premium)

Without a clear structure, process, and governance to meet these goals, confusion will reign and employees will “vibrate in place.” Confusion over roles and pace; lack of clarity in pre-deal strategies and how to translate them to operating plans; and an inability to anticipate and calm customers, suppliers, and employees will likely lead to chaos. Competitors will use this chaos to exploit and poach both talent and customers.

Once this spiral begins, deal value will begin to leak. Lacking functional blueprints that map current-state to future-state processes and the relevant milestones, promised synergies will slip away. Movement toward the new organization will be delayed, eroding employee confidence. Key leadership and talent leave, creating even more confusion. Lack of clarity and planning for synergy tracking can lead to double counting synergies with already planned performance improvements. Failing to understand and orchestrate the interaction and timing of cost and revenue synergies can lead to reducing critical parts of the organization necessary to execute on revenue synergy strategies, possibly even damaging the already expected growth in either company. Cutting too deep can have serious unintended consequences.

On the human side, putting two organizations together can be like a destination wedding where two large families are brought together and meet for the first time at a resort. Will they like each other? The food? What if they don’t get along? Emotions will run high on both sides, and whether or not those emotions are uncovered, they won’t go away. And those emotions will impact employees’ work and how they feel about themselves and the new company.

A successful integration involves seamlessly transitioning the acquired entity into the acquirer’s systems, processes, and culture—or creating new ones—while leveraging synergies and executing a defined strategy to create value and enhance the corporate brand.

To achieve a successful integration, those tasked with leading the integration must understand:

- The Why: Why did we do the deal? What is the strategic rationale of the deal? What are the deal value drivers? What synergies exist and how will we achieve or exceed them?

- The What: What is the new operating model of the combined entity? What pieces will be fully integrated or stand alone? Have the cultural fit, processes, systems, and resources of the target been closely examined and incorporated in the planning?

- The When: When will integration planning and implementation begin? What are investor expectations about when value will be delivered by the acquisition? What parts of the integration will take the most time and consideration?

- The Who: Who are the key company players on both sides? Who will be the integration leader? What crucial personnel will be involved to create and execute the plan? Who’s involved and who gets to make the important decisions regarding the integration? Who are the most important people we absolutely want to retain?

- The How: How will processes and systems be integrated? What steps need to be taken to ensure we comply with regulations and relevant laws to reach a legal close? How will we structure a communications plan that will effectively explain the acquisition internally and externally during PMI planning?

Every acquisition is different, and there is no one answer for how to successfully integrate a target into the acquirer’s business. But without guiding principles and a formal, clearly defined approach to integration (often referred to as “integration strategy”), this disarray will only be compounded, creating a flawed Day 1 and downstream integration problems—content-light communications, muddy decision rights, employee fatigue from overwork and worry about self-preservation, and less than optimal decisions. The pre-deal planning and assumptions from the diligence phase will get lost, leading to missed functional interdependencies, rework, and erosion of the opportunity to expand or accelerate synergies.

If this sounds like a lot, it is, and the ill-prepared will suffer.

Templates versus vision

This is not a process managed with piles of templates—that’s the bad old way. Instead, it’s about providing a guiding vision, structure, and governance that will drive decision-making throughout the two organizations as they navigate the integration planning process.

It’s also about senior management making important decisions up front—like which ERP system (e.g., SAP vs. Oracle) will be the system of choice—so the teams can work on integration planning instead of distractions from predictable political battles. This chapter and chapter 7 provide principles to avoid potential messes and to capitalize on the deal momentum to rally the troops, energize customers, and lay the foundation for results to report to investors and the board. They also show how to minimize disruptions and preserve momentum.

Here, we focus on the role of the Integration Management Office (IMO), a temporary structure that drives the integration, both top down and bottom up. Working with decisions and high-level plans that were created before the announcement, the IMO produces a finer-grained roadmap for success across the new organization, with targeted workstreams focusing on the axes of value that will guide decisions. The IMO will also keep senior executives closely involved through integration planning, since it is their deal vision and strategy that the IMO is executing.

The more planning and decision-making that gets done pre-close, the more that momentum will propel the new organization into Day 1 and beyond to capture synergies, begin post-close integration execution, and operate as an integrated company. The less planning, the less preparation, the more stand-alone the companies will be on Day 1 without an integrated end state in sight—while the cost-of-capital clock is ticking on all that capital that was paid up front. And “ringfencing,” or not integrating the companies, is the start of a death march, leading investors, board members, and employees to ask the question, “Why did we buy this in the first place?” And if they cannot discern a good answer, they will walk away.

Predictable mistakes

In our experience, even seasoned executives make a few predictable mistakes post-announcement that must be avoided.

First, they treat integration as “business as usual”—something to do on top of their day jobs. This approach disregards the sheer amount of work and decisions required and the risks of diverting people who really need to keep the business running against the competition and serving customers. Moreover, they don’t grasp that integrations have many functional interdependencies that leaders in functional roles don’t normally have or assume someone else is solving.

Second, they declare that “everything is important” and fail to prioritize decisions; nor do they establish a coherent governance structure, leading to collisions, disenchantment, and often mayhem. Third, without a roadmap of major decisions, they kick the can down the road, delaying or postponing decisions that are “hard” in the face of uncertainty, sometimes with the hope it will become some other leader’s problem down the line.

Acquirers might also slow decisions in an effort to avoid offending the target company or damaging the culture, or, even worse, will declare to their new employees that “nothing is changing.” That is the perfect way to damage trust early in the process because it will be obvious to everyone that a lot will change. Remember, there has rarely been a “merger of equals”—a phrase that gets used over and again. The fewer hard decisions made up front, the tougher it will be later to achieve the cost reductions or revenue enhancements required to justify the premium. Kid gloves and happy talk can seem nice, but they ultimately lead to negative unintended consequences. Remember, pay me now or pay me later. But you’ll pay either way.

For instance, in one case, during the acquisition of a promising technology company, the acquirer told the target that they wouldn’t do anything to compromise their “secret sauce.” But to the target, everything was part of their secret sauce—from their parking privileges to their free food, generous paid time off (PTO) policies, and office location, right through their killer product (which is what the acquirer thought was the real secret sauce). So once the acquirer started changing policies and systems, the target felt that trust had been broken and talent started walking out the door.

While avoiding the big mistakes is table stakes, the secret to successful integration is in the details. It’s often not the one big mistake that will kill integration; it’s the collection of ongoing small mistakes. The clock is ticking. Integration must be completed while you have everyone’s attention and executive stakeholders agree it is the priority. Trust us: The last thing you want is to call in help two or three years later to assist with an integration gone sideways.

Operating Model and Integration Approach: Bringing the Deal Thesis to Reality

Integration planning starts with the strategic intent of the deal but also with an emphasis on keeping the end state in sight. If the team working on integration plans doesn’t know that intent, or if the strategic intent was muddy, then having a clear vision for the end state and executing on that become challenging indeed. This is one reason earlier chapters have focused on defining a clear strategy and deal thesis from the very beginning of the M&A process.

The deal thesis drives everything that follows. It answers the question of why the acquirer chose to do this deal in the first place, as well as this deal’s logic and assumptions for creating value.

Put simply: Why is the combined company more valuable together than apart? The integration approach of a deal built on cost reductions is fundamentally different than one built on growth. Cost-driven deals will typically look toward back office redundancies, while revenue growth–driven deals (aka strategic deals) start and end with the customer offer. In reality, most deals will be a combination of the two, and there will be a tension between those two axes of value that will have to be resolved.

Focusing on the original deal thesis will help align leaders by providing them with the Why. The strategy underlying the deal will also help answer other fundamental questions about short- and long-term objectives, including level of effort, timing, and role of the various parties involved, questions such as:

- What is the value of bringing these companies together?

- How will the new entity go to market differently?

- Just how much do the two companies need to be integrated, and in what way?

- How fast must organization design move to prepare the organization to operate in an integrated way, with a new operating model in light of changing customer expectations and competitor moves?

- How will the new entity exceed the cost and revenue synergies that were already announced?

Operating model

Each organization will already have an operating model: an organization structure that drives how the business is run in different parts of the organization; a service delivery model that guides how parts of the organization interact and the level of centralization of various support functions; and governance processes, behavioral norms, and decision rights that govern who gets to make specific decisions. Taken together, the operating model is a blueprint for translating strategies into how the organization harnesses its capabilities for delighting customers in a way that creates value for the enterprise. Integration planning necessarily changes some or all of that because the new combined entity will likely have a new operating model.

The new operating model is the answer to how the newly merged organization will run its businesses differently, how it will generate value differently than either organization did before. This includes both the enterprise- and business-level operating models (how separate business units interact and use shared services to support going to market differently) and functional operating models (how people, processes, and technologies may change by function to support the needs of the businesses—from expense reimbursements and travel, headcount approvals, and compliance to outsourcing vs. offshoring payroll, and so on).

The new operating model connects a company’s deal thesis and business strategies with its capabilities, processes, and organizational structure. It informs the answer to such questions as: Given the markets that are key to our future growth, how do we structure our organization to reach them? How much should we centralize services, decision rights, and governance? How should we redesign incentives to promote the right behaviors on the part of employees?

The operating model is not organization design. Organization design, which we discuss in chapter 7, is concerned with roles and people within the new operating model. The operating model itself is all about the changes to come in how the combined organization does business: who does what, where, and when, and how it will be different than it was before.

Remember, the acquisition took place because of an opportunity that was unavailable to either organization, so change must take place. This will potentially mean breaking a part of the organization that appears to be working well to accommodate the future, but it shouldn’t come as a surprise. That might involve, for example, the US DOJ requiring the divestment of a piece of either business. The acquirer shouldn’t be surprised and should already have a general idea of what business areas are overlapping and might require a remedy.1

One example of a new operating model comes from the changes enacted during the merger of two high-technology component manufacturers, each of which earned approximately $2B in revenue the prior year. Both companies owned and operated manufacturing sites across the globe, and each served as an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) to well-known Fortune 50 high-technology and industrial companies. The acquisition allowed the acquirer to double its capacity. But rather than look at this opportunity through a cost lens to drive additional economies of scale, the acquiring CEO took a bold position. He understood that—as happens with many OEMs—they ran a risk of being commoditized and marginalized by their clients. The act of pleasing your customers by reducing cost based on volume is a one-way street to a cul-de-sac where eventually only a few suppliers can survive. No matter how many acquisitions he would pursue, the CEO understood that using this cost focus, despite the very advanced nature of the technology of the plants, the chance that the company would survive and prosper long term would be slim.

The CEO also understood more than many of his peers that M&A can create a powerful moment for change. He was also aware it is the most natural moment where stakeholders—executives, employees, customers, suppliers—ask themselves, “What change will this transaction cause?”

The acquiring company had 14 factories with slightly differentiated capabilities, some which had come to the company through past acquisitions under prior leadership. Each was optimized for its own plan. The target was not so different, with 16 factories. The factories for both companies collaborated but were focused on optimizing their own yields, efficiency, customer satisfaction, and capital investment. The acquisition certainly would offer opportunities for the acquirer to lower the combined G&A costs at HQ, increase purchasing power to drive cost savings on direct material spend, and in certain areas enable advanced technologies in growth markets such as electric vehicles.

But rather than pushing his team to optimize for these opportunities, the CEO insisted that the team restructure the operating model to exhibit a higher level of true end-market intricacy, move up in the market to higher margin offerings, and be known for being the best for something—whether it be electric vehicles, smartphones, or medical supplies.

Rather than having 30 plants and trying to win on quality and price, he forced his team to put the customer end market first and to think of the plants together as capabilities to serve four end markets: communications, automotive, medical, and industrial. The CEO honed in on his vision for an end market–focused company, what its key differentiators were relative to the end market (be it certain technologies important for radar or lidar in electric vehicles vs. quick-turn projects in the communications industry, or specific material requirements in medical), and how they could organize themselves around that vision and exceed the demands of their customers.

The acquisition provided the opportunity to change the paradigm and the value drivers of the company by changing the operating model and incentive structure. This in turn kicked off a rapid process of operational and organization design to not only take care of M&A-related issues, but also those related to combining the two organizations from relatively autonomous plants to a company with four end market–focused business units.

A clear operating model is foundational to a sound integration approach: Why and how the integrated organization is going to operate differently forms the foundation for the concrete choices about how the two organizations will be combined.

Integration approach, governance, and guiding principles

Integration approach—what many call “integration strategy”—involves early decisions aimed at translating the deal thesis into the desired end-state operating model—that is, the approach, governance, and principles that will guide the journey from the present to the future. There are many paths and approaches that one could take, but the integration approach defines the parameters within which this particular merger is going to operate.

Clearly defined rules of the road will help the senior integration team confront the harsh reality at the heart of integration planning—prioritization. Prioritization matters because teams must know what is in scope for the integration, and how to set the right pace and determine if it will play out all at once or in phases.

A clear deal strategy and operating model are essential, but they’re also somewhat theoretical. Integration approach is anything but: Now you have to start facing practical choices.

The five questions at the heart of the integration approach relate to:

- Pace: How fast must the integration get done?

- Degree: What’s in, what’s out, and which parts of the businesses will be fully integrated?

- Phasing: Will the integration happen all at once, or in distinct phases over time?

- Tone: Is it acquirer-driven or collaborative or some combination?

- Communications: What, when, how, and to whom will major decisions be communicated?

Different types of deals will require different approaches. Further, even within typical deal classifications there may be vastly different levels of complexity (from geographic reach to anti-trust considerations), whether it’s a complete transformation that leads to an entirely new organization; a consolidation, combining two organizations in similar businesses into a larger one; a “tuck-in,” where the acquirer absorbs the target; or a “bolt-on,” where the target’s front office is left intact but its back office is integrated with the acquirer’s. While it may be tempting to plot these different deal types into a matrix with rules for each, different deals will often have different characteristics, with some elements of each requiring different integration approaches.

The nature of the deal and its complexity will delimit some of the choices around each element. For a tuck-in with a high premium, for instance, the integration must move fast and happen nearly all at once, with the acquirer setting the tone. In a more complex deal, back office consolidation might need to happen quickly, but rationalizing the supply chain might take longer and require more collaboration in certain areas than in others. Combining two different ERP systems may require an interim-state operating model where both systems run in parallel for at least a year until the cutover to one system can happen.

For example, two large cosmetics companies with operations across multiple geographies and with two distinct operating models in the United States merged in what might be called a consolidation deal. One was strong in the mass self-serve market (e.g., Walmart and Target), while the other focused on large department stores that use beauty advisers. The first phase of the integration was back office consolidation and commercial integration where, although there was some channel overlap, operating models were kept intact. Immediately though, there would be one face to customers (retailers). The next phase focused on supply chain integration that involved warehouse consolidation and the insourcing of the target’s fragrance production. The third phase was the “long-pole in the tent” and focused on uniting disparate ERP systems.

Before establishing the IMO, which will oversee the monumental day-to-day tasks of the sprint to Day 1, the new CEO will meet with their direct reports that have been chosen (what we call L1 leadership) and the IMO lead to establish a common understanding—the broad outlines and expectations—of how the integration will proceed, particularly around decision rights. They will agree on what types of decisions will need consultation with the L1 team, which may not be involved with the integration day to day, and those issues that would require escalation to the board. The board in its oversight role should be well informed about the approach and governance for the integration.

Among the decisions will be the composition and role of the executive steering committee (SteerCo)—the ultimate arbiter of major decisions. SteerCo often comprises at least the CEOs of both companies, especially in large material deals. It can also help to have either the COO or CFO who has been involved from the beginning of the acquisition so they can explain potentially confusing financial aspects and synergy expectations of the deal. SteerCo can ratify decisions being recommended by the IMO, clarify strategic questions about the deal, referee big conflicts that the IMO leadership can’t resolve, and greenlight and fund synergy programs.

The CEO and their team must also be clear on the guiding principles consistent with the tone of the integration. Is the acquirer in complete control, or will the process be more collaborative? If the merger is going to be guided completely by the acquirer, be clear about this fact up front. It could be a combination of the two, where the sales teams will collaborate and use best practices of both, but the back office processes and systems will move quickly and follow the acquirer’s approach.

Other principles might include decisiveness over perfection, speed over elegance, roles before people, guidance like “Don’t struggle in silence,” using “we” and not “us and them,” or not taking actions that would threaten current customer satisfaction. While some of these may be defined by the deal, larger, more complex deals will require explicit principles for different businesses that will help guide the integration over the longer term.

In effect, integration approach and guiding principles help to set expectations for the new organization. The senior team must make sure the approach is logical given the economic rationale of the transaction and that their subsequent actions are consistent with the expectations they set for their organization. In times of tension and doubt, management and employees will need to feel confident the senior team is all on the same page.

The integration approach also makes clear what trade-offs are acceptable. “What will you sacrifice?” is a fundamental question in this process. No synergy, no change, comes for free or without risk. EPS may need to be sacrificed initially to have a smoother integration that will create more value later. Restructuring may require spending precious capital now to replace the IT stack or hire staff or replace the ERP. These may be truly necessary to create an integrated organization, and yet risk EPS in the short term. Is that OK, or is it off the table? What in fact is non-negotiable? Questions like these must be addressed and answered before kicking off an IMO. Many of these decisions will be communicated at kickoff meetings (which we address in the IMO section, below), but they have to be decided earlier in broad outlines by senior leadership.

A useful example of both setting approach and principles, and making trade-offs explicit comes from Deloitte Consulting’s acquisition in May 2009 of the federal practice of BearingPoint, KPMG’s former consulting arm—a major transaction for Deloitte. BearingPoint was more than twice the size of Deloitte’s federal practice in both revenues and people. In the Department of Defense (DOD)/intelligence sector, for example, revenue increased from $14M to over $150M with the deal.

Deloitte’s federal practice leadership were emphatic about retaining BearingPoint’s talent. Consulting is a relationship business where leaders directly generate revenues. “Startling the herd” could result in a massive exodus of talent. Yet each firm had a radically different operating model when it came to staffing teams. At Deloitte, professional staff came from a general staffing pool that partners had to compete for, whereas at BearingPoint partners “owned” their dedicated staff.

Deloitte leadership made the decision to proceed with the Deloitte operating model but to move slowly to avoid having employees feel like they were being forced into anything: “We need them to stay” was a guiding principle. Leadership met personally with each leader from the seven sectors of the BearingPoint practice—nearly 75 of them—showing a genuine interest in their development and career path at Deloitte as well as their general well-being. Deloitte spent an entire performance cycle crafting new roles and goals where the focus was on keeping staff whole—that is, neither penalized nor marginalized because they didn’t come from Deloitte.

Another important guiding principle was avoiding the use of “us versus them.” “We” now had a bench of talent that could recruit better candidates, serve larger clients, had better relationships, and could propose on much larger projects. Over three years, the combined platform grew rapidly, with newly recruited professionals making up nearly one-third of the business.

One thing that did have to go fast—very fast—was preparation for Day 1, barely six weeks after announcement. That huge undertaking required arming roughly 4,250 new Deloitte employees with their new badges, laptops, email and network credentials, and compensation and benefits packages on Day 1. Onboarding for Day 1 was so enormous that Deloitte rented the Washington, DC, convention center for the event. Deloitte’s federal practice has become well known as one of the major players in federal consulting, and the learnings from that integration have benefited clients as well as the firm’s subsequent professional services deals.

Here, you can see how a thoughtful approach and principles can guide the plan to integrate successfully, and quickly where necessary. Those principles and the integration approach go beyond mere planning and affect the employee experience and preparing for Day 1 (topics we address in depth in chapter 7).

The Integration Management Office: Supercharged Conductor for Integration Planning

The IMO is the living and breathing—albeit, temporary—structure that leads integration efforts. It remains separate from the ongoing business by design and facilitates bottom-up and top-down governance. The IMO identifies what must get done by Day 1 and by the end state (what we call the Day 1 and end-state “must-haves”). It identifies the risks of delivering within that scope—and helps reach consensus about what is a non-negotiable priority for Day 1 or what can be deliberately postponed. When conflicts arise or there are competing priorities, the IMO makes the call or escalates the issue to the executive SteerCo. M&A strategy, due diligence, valuation, and announcement are focused on creating value for the acquirer, and the purpose of the IMO is to direct and accelerate the execution to realize that value.2

The IMO must be a supercharged prioritization machine for organizing and establishing workstreams, gathering information and ideas from both the acquirer and target, raising issues and problems that need to be solved, setting synergy targets by business and function, developing ideas that will translate to projects for delivering those targets, making decisions, and identifying Day 1 versus end-state must-haves and interdependencies that must be managed across workstreams for Day 1 and beyond.

The job of the IMO is to fulfill the promise of the deal strategy and the new operating model, and to avoid the muddy confusion of jockeying teams operating in their silos. It should propel the new organization through Day 1 toward the end-state operating model.

The pace and amount of work can feel overwhelming, especially given the short amount of time available. And it’s true: This is a sprint. Take a deep breath.

Integrating two organizations for reasons that initially might not be well understood or where there are many opinions of how things should be done is a lot like being the conductor of an orchestra. The role of the IMO is—more than anything—that of a conductor, orchestrating the integration teams’ attention on the right things to do at the right time, within legal guidance and regulations. No doubt there is a lot of talent on both sides. The target’s talent didn’t get there by accident, and that may be a big reason you wanted them in the first place. But self-preservation and what’s best for their function or business will be their focus. That’s true for the talent of the acquirer as well. IMO leadership must prevent that by launching a coordinated effort.

IMO governance prevents people from running around doing their own thing and making their own decisions—which leads to chaos and confusion, and to people vibrating in place, full of anxiety and uncertain of what to do. In this role, the IMO is a sequencing and prioritizing body, aiming to get the bare minimums needed for a flawless Day 1, with no negative customer or employee impact. The IMO also serves a controllership function. It monitors and challenges the estimates of one-time and ongoing costs emerging from the plans of the workstreams for operational integration activities as well as synergies.

The IMO allows for decisions to be recommended deep within the integration workstreams (bottom up) driving to decisions that will be ratified by the SteerCo (top down) regarding organization design and leadership, synergy planning and tracking (both labor and non-labor), and the transition to post-close execution of the end-state vision for the combined company. The IMO must be nimble such that leadership can make decisions quickly and revise them, if necessary, as new information emerges.

While the IMO structure is essential to integration, it can’t be overengineered or have too much process because that will result in the opposite of what it is intended to achieve—speed, agility, efficiency. An additional danger exists in focusing too much on process: Teams’ focus can shift from defining and tracking results to just publishing their reports. Moreover, the IMO is transient. If it lasts too long, it will leave a legacy of processes that aren’t useful to the new organization. Don’t forget: The IMO is dispensable once you transition to business as usual.

In fact, part of the IMO’s remit is to define when the IMO itself will be fully disbanded. Defining what “done” means—when the integration is complete—is an integral part of planning and will vary across integrations depending on the complexities and interdependencies of the workstreams. The executive team and integration leads will need to know when they’ve crossed the finish line. In the ideal, the end state is defined as when the two companies are operating in the marketplace as one and the value of the deal thesis is well on its way to being fully realized.

Leadership, workstreams, and staffing

Leading such a complex program—even a temporary one—requires gravitas. The head of the IMO, the integration executive, must know the businesses and the deal strategy, and also must be able to command respect and get business leaders in the acquirer and target to do what they must to support the necessary integration activities. Executives and other leaders may be resistant to change as the shape of their work lives shift and, without clear direction, may do what they think is in the best interest of the combined organization—which may be at odds with the integration strategy itself.

There’s no other way of saying this: The integration executive will make or break success. The more that must get done, the stronger the IMO must be. Having a weak program head is one big step toward failure. The integration executive must be able to muster dedicated resources both in terms of full-time staff and attention from other leaders in the organization. They should also have access to the CEO.

In one of the most successful mergers that we’ve been involved with (which we discuss in more detail at the end of this chapter), the CEO chose the head of the most successful and largest business unit to run integration. Such a high-profile appointment served as a signal to the entire organization of the importance being placed on the integration, and it also helped the IMO get the resources and attention it needed to get the job done. This may seem paradoxical—taking a strong leader and using their talents in what seems to be routine project management—but running a major integration effort is anything but routine.

The IMO leader has to be an effective decision-maker. They will refine the master narrative—the compelling vision for the deal—and drive change and communications, set the pace for the timing of operating model–related decisions, oversee the efforts of the clean teams, organization design, and synergy planning, and identify major post-close initiatives that will drive the majority of the deal value.

Choosing the IMO leader must reflect the importance of the integration. That said, choosing the IMO leader also means clearing their plate because they will need to have sufficient time to do the job meaningfully and successfully. The role is going to be intense.3

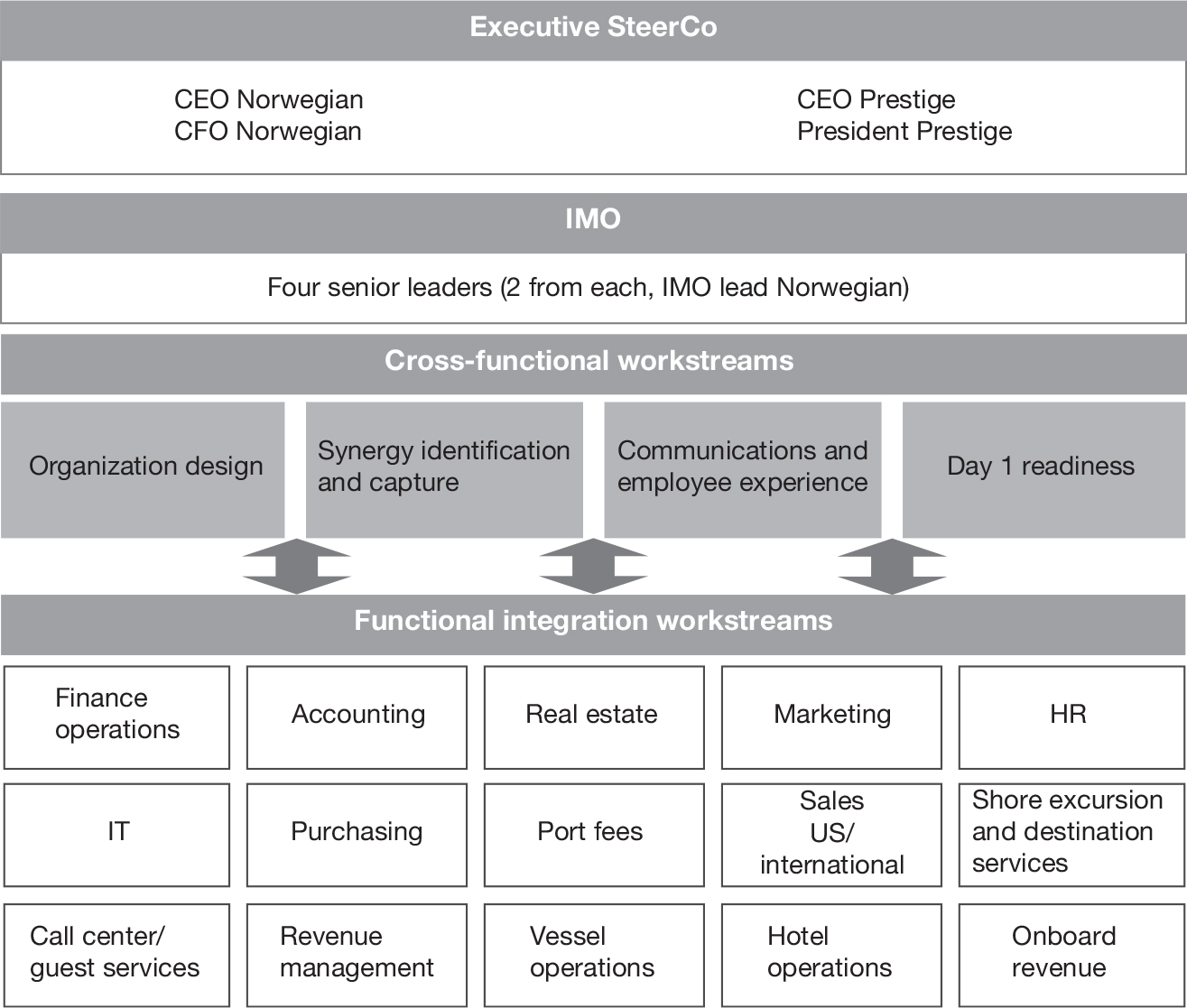

The IMO manages the workstreams that make up the integration planning structure. Beyond typical functional workstreams such as legal, HR, IT, and finance, there may be other workstreams linked to the new enterprise operating model such as insourcing previously outsourced activities or the merging of businesses. For Norwegian Cruise Lines Holdings, which we discussed in chapter 5, that meant workstreams such as vessel operations, call centers, and shore excursions. Each workstream might break into multiple sub-workstreams with their own leadership, charters, and synergy targets. For example, finance will typically have tax, treasury, and FP&A workstreams that report up to the finance functional leaders. (See figure 6-1.)

Norwegian’s integration management structure

There will also be workstreams that cut across all the others. These cross-functional teams (the subject of chapter 7) will typically focus on organization design, synergies, communications and employee experience, and Day 1 readiness. For carve-outs, where you are buying a business from another company, transition services agreements (TSAs) would be a common cross-functional workstream. Cross-functional teams are essential not only because they enable collaboration across functions and crystalize interdependencies, but also because they acknowledge and help lessen the political conflicts that often arise.

Staffing the leadership of the workstreams and sub-workstreams is an important early step in the process of the two organizations learning about each other. Workstreams are typically staffed with the relevant functional or business leaders from both parties—often called “two-in-a-box.” This approach allows the full benefit of expertise, knowledge, and idea sharing from both sides—and the opportunity to collaborate to achieve quick wins. It is big mistake to underestimate what you can learn from the business experience of the professionals on the other side.

As one of our colleagues quips, “You need to pick the right people, not the wrong ones.” What she means is that you may be tempted to pick people to lead the workstreams who aren’t busy, who, if they’re seconded to the IMO structure, won’t derail business as usual. This is a mistake. The best people are actually the busiest; they will want to get things done so they can fully move back to their business units or corporate positions. This approach isn’t without danger. It can endanger business as usual today. There can also be tension between leaders’ day jobs and the IMO. Indeed more than tension—the jobs that leaders left to participate in the IMO may not be there when their temporary assignment is disbanded. But if you’re aware of that risk, you can make sure those talented employees go back to great jobs in the new organization after planning and execution are complete.

Governance and cadence

The IMO structure ultimately reflects the decisions that have already been made about the new operating model. It engineers kickoff meetings, the cadence of weekly meetings with IMO leadership, external advisers and SteerCo, and interdependency workshops. It sets and assigns synergy targets, leads the development of a prioritized set of initiatives and projects that will deliver synergy targets, facilitates communications, sequences post-close priorities, and facilitates decisions and actions required for a successful Day 1. (See the sidebar, “Enabling Technologies for Post-Merger Integration.”)

How big should the IMO and workstream structure be? As with any question like this, the answer is that it varies. IMO dynamics are driven by scope, scale, and degree of integration—by complexity. And remember: Deal size doesn’t always equate with complexity (although it often does). Complexity depends on the deal’s strategy, the operating model, and degree and kinds of change that will be required during the integration.

A typical weekly cadence starts with a meeting of the integration leader and other members of IMO leadership, which typically includes senior finance leaders from both sides. In that meeting they will talk about the focus areas of the program for the week: major decisions that will need to be made and actions that the integration leader will need to take to push the agenda and mitigate risks. This allows the IMO to act as a forcing mechanism to get teams focused on the right things. At this meeting, leadership reviews activities and reports of the previous week to ensure that the right issues are being raised and prioritized issues are getting resolved, that teams have appropriate resources, and that the synergy program is on track.

Some of this may sound mundane—a workstream may fail to meet its weekly goals and is off track simply because it has insufficient resources—but such a review and setting priorities for the week are essential to keep the program on track through Day 1.

Enabling Technologies in Post-Merger Integration

Several PMI technologies have been developed that enable an acquirer to understand the enormity of the data and information flows that exist, rapidly identify critical decisions, design future-state processes, plan for and track progress of integration plans, measure employee sentiment, and manage complexities inherent in large international deals. They enable the acquirer to keep track and manage an immense amount of data, glean insights, model possibilities, commit to a plan, and track progress against the plan—and connect all the dots so teams are not operating in silos. Such technologies include:

- Project management tools, which offer a setting that allows teams to collaborate and share their ideas, data, plans, dependencies, and decisions. That includes serving as a central system of record for new operating model design, blueprints, status reports, synergy planning and tracking, SteerCo and IMO decisions, meeting minutes, plan updates with timelines and upcoming deadlines, and ongoing interdependencies.

- Organization visualizer tools, which give teams their first real look at the combined workforce as it exists today, beyond a list of names in an Excel file or paper org charts. This allows leaders the ability to confirm the baseline organization and discover structural inefficiencies (too many managers or too few) inherent in each organization before any design decisions are made and to model and contemplate many possible alternatives for the new organization.

- Culture diagnostic tools, which act as a survey that asks questions across several dimensions including differentiating dimensions such as shared beliefs, inclusion, collaboration, sense of pride and ownership, tolerance for risk and ambiguity, and so on. These tools offer an understanding of the current state of each culture, where there are similarities or differences that might create complementarity or conflict, and how to work best together.

- Change management tools, which act as a database to enable tracking of all the changes that will happen, to whom, and when. These tools capture change impacts, anticipated reactions to change, planned interventions, status of deployments, participation rates in change interventions—essentially monitoring the efficacy of the change programs so you can course correct if needed. All of this information can integrate into the central project management tool to allow leaders visibility to groups that may be unprepared for the change that is about to come.

- Contract management tools, which use NLP to identify, extract, and review contractual data—terms, dates, parties, and so on—at a fraction of the time and cost that any human could. Acquirers can rapidly prioritize opportunities for proactive renegotiation before contracts’ auto-renewal, achieve better terms with suppliers and customers, and ultimately accelerate synergy realization.

Tuesday can involve a one-on-one meeting with the IMO leadership team and each workstream to deliver the weekly status report, a snapshot of the health of a workstream. This is a grueling day and can be unpleasant because some workstreams are falling behind and may be defensive. The meetings stretch all day, one after another, and can be exhausting. But they are vital to make sure each workstream is on track and allow the IMO leadership visibility of emerging interdependencies, Day 1 non-negotiables, legal and regulatory hurdles, progress on synergies, and anything that might impact the new operating model. Here, it will be clear if the work is on track and if the right resources are in fact in place.

These meetings focus on three topics:

- Progress to plan

- Proposed mitigation strategies if not on schedule

- Decisions

Status reports are especially helpful in spotting when a risk or major issue is on the horizon, but such reports shouldn’t require so much detail as to slow teams down. Beyond updates, integration leadership also has the overall view that allows it to surface interdependencies across the workstreams and make required decisions. Making decisions early allows them to be revisited if they don’t work out as planned as the path forward becomes clearer. Depending on the number of workstreams, these meetings may take a couple of days—every week.

Thursday or Friday will typically involve an all-hands meeting between all workstream leads and the IMO leadership. That meeting will focus on the outcomes of cross-functional decisions that affect the program as a whole. It will also involve strategy decisions that are going to SteerCo (SteerCo itself could be monthly at first but will meet more frequently as legal close for the transaction approaches).

It’s always going to seem like there are too many meetings. People will complain, particularly when the meetings are not well orchestrated or not meaningful or productive. But it is vital for the cadence to drive open communications so that people don’t act in silos, ultimately slowing the process while they make misaligned decisions that will inevitably need to be revisited. Making decisions in silos means getting the right parties back together to revisit decisions and discuss alternatives, going back through integration leadership, assessing other decisions that were predicated on those made in the silos, and so on. When leaders struggle to make decisions, IMO leadership must influence those workstream leaders to act.

Workshops and tasks

Kickoff meetings mark the official launch of integration planning. The IMO brings leaders together from both sides—in person or virtually—who will lead the functional and cross-functional workstreams. They provide a platform to gain initial buy-in and to generate excitement on the tenets of the deal strategy, strategic goals, synergy targets, integration approach, and functional implications of the strategy. These meetings are designed to energize the teams and rally the troops who will execute on the new operating model and, at the same time, set the tone for the pace and urgency that will need to be sustained though close. Kickoff meetings should launch as early as possible after announcement to stop chatter and rumors, and to provide facts along with direction of what comes next.

Regardless of whether IMO leadership requires workstream leaders to write charters that set direction and high-level goals for what the workstreams are expected to accomplish or hands out goals to the workstream and functional leaders, everyone must leave these meetings with a clear sense of purpose. They should be able to tell the same story when they get the inevitable questions from colleagues who aren’t part of the IMO structure—consistent with the master narrative of the logic and vision of the deal.

Participants leave a great kickoff meeting knowing what they need to accomplish in 30-, 60-, and 90-day sprints, their synergy targets and any initial issues, other workstreams they will need to collaborate with (interdependencies), and a preliminary view of Day 1 non-negotiables and requirements specific for their workstream (e.g., safety, country-specific regulations).

These meetings also establish rules of the road and guiding principles for ways of working, which we discussed earlier in this chapter. Is the acquirer in complete control or is the merger more of a collaboration between the acquirer and the target? The IMO leads will lay out the guiding principles of how the two organizations will work together, including how decisions will be made, transparency, tenets of the customer experience, speed over elegance, decisiveness over perfection, human guidance like “don’t struggle in silence,” and acceptable trade-offs.

Rules of the road will also include integration planning dos and don’ts related to potential anti-trust issues. Anything that involves the sharing of competitively sensitive information is prohibited, as is making joint business decisions or coordinating marketing or pricing decisions. Clean rooms are required for that. However, sharing and planning office space and facility optimization, IT systems, or financial controls are generally without restriction.

This is a lot of work, and it must move quickly. Many organizations fail to move fast enough and waste substantial time before and immediately after Announcement Day. Don’t be one of them. Time is not on your side.

Following the kickoff meetings, teams will be focused on functional blueprinting: a map of changes from current state to future end-state processes and technology requirements—the must-haves. Their other focus will be detailed planning for an issue-free Day 1, from financial funding of the deal and any required changes to the legal entity structure to avoiding negative customer and employee impacts, and what employees will want and need to know.

Once workstreams develop their major planning milestones for close, the IMO is ready for an interdependency workshop. Here, each workstream leader walks through their major milestones from now until close, showing each team’s path to get to legal close and aligning the critical milestones across workstreams—we call this “walk the walls.” This will allow IMO leadership to identify interdependencies between, for example, the tax workstream determining the future legal entity structures and the legal workstream completing the process of getting those legal entity structures in place and filing appropriate regulatory documents for a legal close. Any potential misalignments on upcoming key dates can cause big trouble. The timing and activities of many workstreams such as finance, procurement, and HR will be highly dependent on IT enablement for activities such as paying suppliers and employees across both organizations on Day 1. There will be a long list. Now is the opportunity to make sure interdependent teams are aligned and coordinated.

Ecolab Acquires Nalco

One of our favorite and most successful deals is Ecolab’s acquisition of Nalco. Ecolab’s approach illustrates the impact of using the deal thesis to guide the integration planning. Ecolab’s IMO delivered the initiatives and projects that drove the value of the deal and the future of the combined company.

In 2011, Ecolab, a leader in cleaning, sanitizing, and infection prevention, acquired Nalco, a company specializing in water treatment and processing solutions in a transaction valued at $8.3B. Prior to the transaction, both Ecolab and Nalco were demonstrated growth companies with global reputations for innovation and customer service. Nalco’s strong intellectual property portfolio, customer base, and field sales model complemented Ecolab’s, particularly in the water business and in emerging markets. You see their products and service trucks everywhere—from the cleaning carts at hotels to oil fields.

Ecolab had completed roughly 50 smaller transactions in recent years, but Nalco was a mega-deal, many times larger than their average deal, and presented the opportunity to create something that could be transformational. The acquisition positioned Ecolab ahead of several mega-trends: rising energy demand, increasing water scarcity, growing public concern about food safety and security, and, finally, accelerating growth in emerging markets. The size of the deal also brought larger risks: that Ecolab would realize neither the cost synergies nor the acceleration of growth that would be required to justify the price. The deal was anything but normal.

To lead the integration, Doug Baker, Ecolab’s CEO, chose Christophe Beck, who led one of Ecolab’s largest businesses—the institutional business. Christophe was a surprising choice given how important he was to the company, but his appointment was a bright signal to executives and employees of just how important the integration was to the company’s future. While many leaders will say they’re going to have a great Day 1 and capture or exceed synergies, Christophe made the bold statement: “This is going to be the best integration ever.”

Christophe insisted on a full-time team of leaders from both companies with clear reporting lines and responsibilities. He also insisted that the integration team be co-located, which allowed for the immediate resolution of issues and emerging interdependencies. Every meeting started with a reminder of how many days it had been since Announcement Day and how many days remained until Day 1. This “stopwatch” helped provide a sense of urgency and galvanized the teams to keep on track.

Ecolab created a tailored integration approach branded as “Winning as One,” and launched the IMO with three overarching priorities, each the focus of a dedicated team: Capturing Hearts, Delivering Synergies, and Accelerating Growth:

- Capturing Hearts: This team’s planning anticipated the uncertainty and disruption to come inside and outside the organization. Their planning focused on retaining 100 percent of their most valued customers while maintaining a strong safety record. They also planned for a smooth employee experience for Day 1 and beyond.

- Delivering Synergies: With the goal of making the combined business as streamlined and efficient as possible, this team oversaw the planning for cost synergies. Large savings were expected from global shared services, facility optimization, and immediate savings, post-close, from procurement (using a clean room).

- Accelerating Growth: The goal for this team was to use the combined company’s expanded capabilities and complementary market access with major institutions to grow existing core businesses, bring innovations to market through bold new plays by combining chemistries like antimicrobials in energy services, and accelerate presence in emerging markets. For example, Ecolab sold drapes and hand sanitizers to large hospitals while Nalco serviced large hospitals maintaining boilers and chillers. The team pursued large opportunities for cross-selling and creating bundled offerings for major customer wins. These growth synergies were planned and would be tracked as meticulously as the cost synergies.

With the mantra of delivering the “best integration ever,” Ecolab set up a global integration office to drive integration strategy and planning, as well as regional integration teams in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Latin America. This structure allowed for rapid issue escalation and facilitated a consistent worldwide approach. There were clear governance principles: Functional teams tackled function-specific issues; business teams addressed cross-functional priorities such as synergies, employee experience, and operating model design; and regional teams led the local execution.

The overall financial objective was to deliver an EPS of $3.00. The IMO and workstreams developed their projects and milestones with that goal in mind. In just 61 business days, the IMO and workstreams delivered several layers of initiatives and projects. Twenty mega-initiatives drove the three priorities (capturing hearts, delivering synergies, and accelerating growth). Those initiatives translated into 115 major projects (and 495 sub-projects). Each project stated the activity, start and end date, person accountable, and the corresponding benefits and cost to achieve—ultimately approved by the SteerCo and primed to kick off implementation on Day 1.

Ecolab illustrates the intense, interlinked work of the IMO, and how the layers of reporting, workstreams, initiatives, and projects must be designed to support the overall goal rooted in the deal thesis. Without strong leadership, considered structure, and constant orchestration, the sprint to Day 1 will not set up an acquirer for success.

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on the structures necessary to govern and control the integration process, most especially the IMO and its leadership. Integration planning cannot be a process where leaders fill out templates or prepare stacks of forms that are destined for a series of massive three-ring binders—although, years ago, it used to be. Today, integration planning focuses on providing a guiding vision and structure that will drive decision-making throughout the firm and throughout the process. The IMO will take the logic of the deal, the new operating model, and its guiding principles, and translate those into a tightly controlled course of action across many teams and workstreams to achieve the promise of the new end-state vision that will deliver more value to customers and shareholders.

Chapter 7 addresses the major cross-functional workstreams that the IMO will manage. These include designing the new organization, synergy planning, communications and the employee experience, and the sprint to Day 1—and setting up the combined organization for success on Day 1 and beyond. We also discuss the additional planning complexities of divisional carve-outs and associated TSA’s with the seller.