CHAPTER 1

The Acquisition Game

Once upon a time, mergers were sexy. They were perfectly glamorous. Filled with flamboyant corporate raiders, junk bonds, and coercive hostile takeovers of the 1980s and the all-stock mega-deals of the 1990s internet boom, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) grabbed front-page headlines seemingly every day.

But something went wrong. And “synergy” was getting a bad name.

By the early 1990s, evidence began to emerge from prominent academics and consulting firms that a majority of deals actually hurt the shareholders of corporate acquirers, several even resulting in bankruptcies.1 In October 1995, BusinessWeek published the groundbreaking story “The Case Against Mergers,” based on research showing that fully 65 percent of major deals destroyed value for the buyers’ shareholders. Acquirers were regularly overpaying for alleged synergies, and investors knew it.2

Unfortunately, acquirers continue to disappoint today.

Yet few other tools of corporate development and growth can change the value of a company—and its competitive future—as quickly and dramatically as a major acquisition. Material M&A deals are major “life events” in the story of a company’s history. Although the welfare of employees and customers are paramount, any deal’s success will ultimately be judged like any other major capital investment decision: Did the allocation of capital and resources create superior shareholder returns relative to competitors?

Most material acquisitions even today do not deliver on their promises and hurt the shareholders of the acquirer. Although the shareholders of selling companies routinely benefit from the significant premiums that acquirers pay, returns to the shareholders of acquirers, on average, fall far short of expectations. Instead of giving investors the reason to buy more of their shares, acquirers are often giving them clear reasons to sell. And initial market reactions of investors, positive or negative, are on balance a reliable forecast and indicative of future results. Acquisitions usually fail, and investors can smell a rat.3

The questions are Why? and What do we do about it?

Our hypothesis is that these systemic failures are the result of a lack of preparation, methodology, and strategy. Most companies don’t have a real M&A strategy in place. They haven’t thought through the deals they believe are the most important versus a universe of others they have no business even looking at—they have few priorities. They jump into an auction or hire a banker who comes up with a few available acquisition targets and promises of synergies. Teams are quickly assembled to perform whatever operational or commercial diligence they can complete in a compressed time frame while the CEOs and bankers negotiate the price. They present the deal to the board, often with little consideration of how the synergies will actually be delivered, but with an urgency to approve. The implicit threat is that if the board can’t see their way to approving the deal, there may be nothing else this good on the horizon. One prominent CEO called it the “Wow! Grab it! acquisition locomotive.”4

Announcement Day arrives in the form of a carefully staged conference call packed with journalists and analysts—and plenty of excitement.

Then investors react. For the majority of companies, it’s a harsh surprise, with the acquirer’s stock dropping—investors (who include employees, who are also owners) feel the pain immediately.

Despite all the hard work that both the acquirer and target do, investor reactions tend to be right on the mark. The promised synergies never develop, or at least not at a level to have justified the price; employees don’t understand how the deal will impact their futures; and the new company is a mess, destroying significant value for the firm and its shareholders. They rarely recover their losses.

We want to improve your odds for successful M&A. The Synergy Solution aims to change how companies—managers, executives, and boards—think about and approach their acquisition strategies. Beginning with the well-accepted foundation of the economics of the M&A performance problem, we’ll guide acquirers through how to develop and execute an acquisition strategy that both avoids the pitfalls that so many companies fall into and creates real, long-term shareholder value. We’re not looking to make mergers sexy again. But we are aiming to make mergers work—for acquirers and for their shareholders.

Then and Now: The Evidence

While some claim that things have gotten better—that companies and their managers are better at evaluating acquisitions and realizing the predicted synergies—we’ve discovered that, empirically speaking, things aren’t much better at all. Moreover, investors continue to listen carefully to the details of what acquirers tell them about their major deals.

We updated Mark’s landmark study of the 1990s merger wave (the basis of a BusinessWeek cover story), and our findings support the case that even after all the deal activity of the past several decades—and all of that opportunity to learn—there is still plenty of room for improvement.5

Let’s take a closer look.

For our study, we drew from well-known data sources Thompson ONE and S&P’s Capital IQ and examined more than 2,500 deals valued at $100M or more that were announced between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2018. We used publicly available data so that anyone can replicate our results. We excluded those deals where the acquirer’s share price could not be tracked on a major US stock exchange. Using the rationale that a deal had to be material, we excluded those deals in which the market capitalization of the seller was less than 10 percent of the acquirer’s. Finally, we culled deals in which the acquirer subsequently announced another significant acquisition within a year.

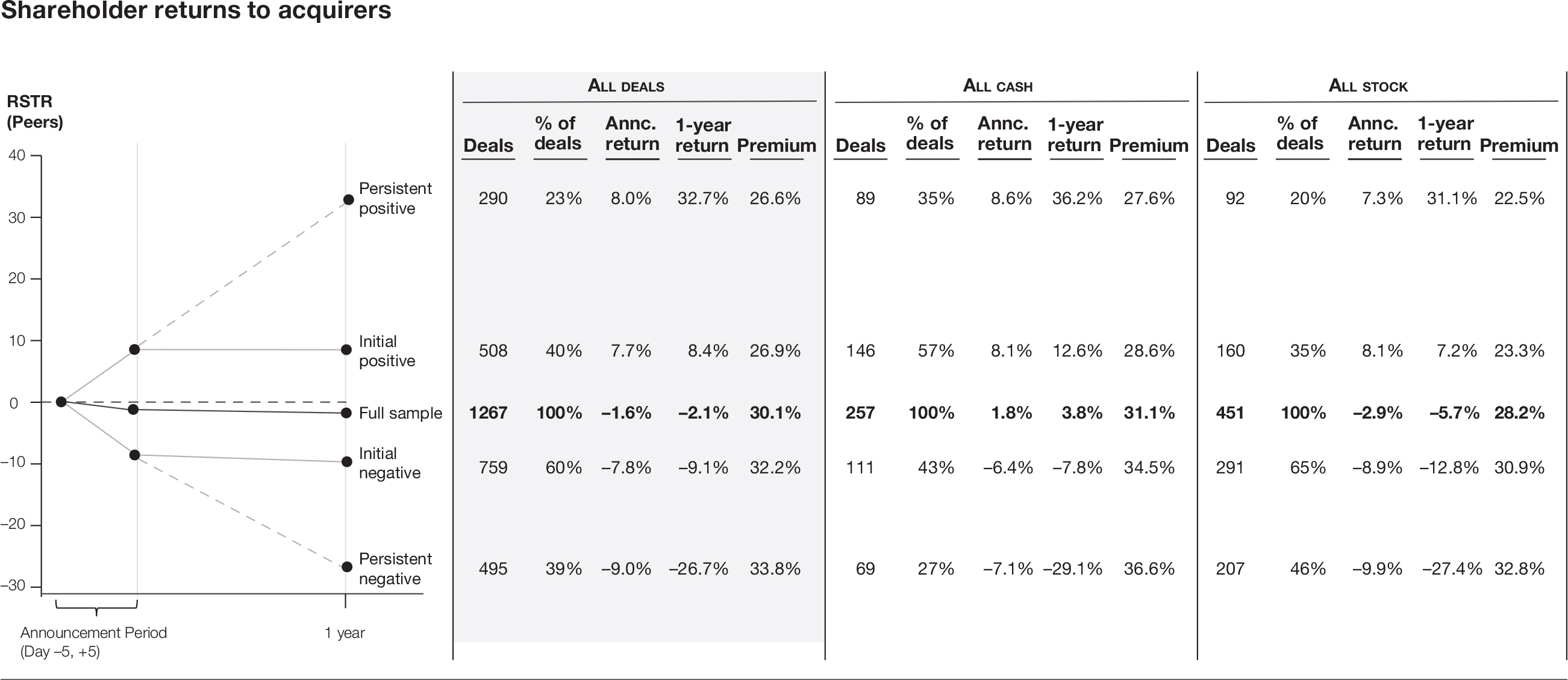

That yielded a sample of 1,267 deals representing $5.37 trillion of equity value and $1.14 trillion of acquisition premiums paid over the 24 years of our study. The average equity market capitalization, five days before announcement, was $9.3B for acquirers and $3.8B for sellers. The average market capitalization of sellers relative to their acquirer was 46 percent. These were by any measure very significant deals for acquirers. The average premium paid was 30.1 percent, or $902M.

We measured how acquirers performed around deal announcement using the 11-day total shareholder return (five trading days before to five days after) and how they performed over the course of a year post-announcement (including the announcement period). While one year may seem a short period in which to judge success or failure, the first year is critical to deliver performance promises because it signals the credibility of those promises.6

We examined both raw total shareholder return (stock price appreciation plus dividends) and total shareholder return relative to each acquirer’s industry peers within the S&P 500, as classified by Capital IQ.7 We report the industry-adjusted total shareholder returns (often called RTSR, or relative total shareholder return).

What did we find? The key results for our sample of 1,267 deals are outlined below.

Acquirers, on average, underperform their industry peers

Average returns to acquirers for these major acquisitions around deal announcement were −1.6 percent, with 60 percent of deals viewed negatively and 40 percent viewed positively by the market. One year later, the average returns for these acquirers were slightly worse at −2.1 percent, and 56 percent of acquirers lagged their industry peers. As with any study on M&A, there is a wide range of results, so these are just the averages.8 Our overall results certainly suggest we should stop using the still widely cited statistic on M&A performance that 70 to 90 percent of deals fail.9

That said, acquirer performance was pretty bad in the 1980s and 1990s merger waves where nearly two-thirds of deals destroyed value for the acquirer.10 There is some encouraging news here. When we split our sample into three eight-year periods covering three merger waves—1995–2002, 2003–2010, and 2011–2018—we found that acquirers have improved from 64 percent negative deal reactions to 56 percent in the most recent merger wave, and initial market reactions have improved from −3.7 percent to nearly zero; but one-year returns remain challenged, with a −4.2 percent one-year return in the latest eight-year period. (See appendix A for detailed data and results of the study.)

Despite what might be an encouraging sign, we’re still not out of the woods. To put it bluntly, while M&A, on average, may be getting slightly better, it’s just “less negative” overall.

Let’s de-average these results and look deeper.

Initial investor reactions are persistent and indicative of future returns

Many observers believe that stock market reactions to deal announcements are mere short-term price movements and don’t offer predictions of future success or failure. One CEO famously said, after a near 20 percent drop in the company’s share price on the day of a major acquisition announcement, “You don’t make this kind of move, and judge its success, by the short-term stock price.”

To explore the assertion that initial investor reactions don’t matter, we divided initial reactions into a positive reaction portfolio and a negative reaction portfolio. If market reactions don’t matter, then both portfolios should trend to zero. They don’t.

One year later, the portfolio of 759 deals that began with a negative reaction of −7.8 percent earned an even stronger negative return of −9.1 percent. The portfolio of 508 deals that began positively with a return of +7.7 percent maintained a strong positive return of +8.4 percent. A closer look shows that 65 percent of the initially negative deals were still negative, and 57 percent of initially positive deals were still positive a year after announcement. So, while a positive start is no guarantee of future success, especially if companies do not subsequently deliver on promises, a negative start is very tough to reverse, with nearly two-thirds of deals still negative a year later. And it’s even tougher for negative reaction deals that use stock as currency: Nearly three out of four all-stock deals (or 71%) that were initially negative were still negative a year later.11

Bottom line: Initial market reactions matter.

Delivering results after a good start pays off big—and the opposite is true

Deals that began in a positive direction—and actually delivered—dramatically outperformed deals that began poorly and were persistently negative—what we call the “persistence spread.” In the year following announcement, acquirers whose deals were met initially with a negative investor reaction, and continued to be perceived negatively, posted an average return of −26.7 percent; whereas acquirers whose deals initially received, and continued to receive, a favorable response, returned an average of +32.7 percent—a persistence spread, or difference in returns, of nearly 60 percentage points.

Not only do initial investor reactions matter a lot, they matter a lot in a way that should be very important to acquirers.

Figure 1-1 illustrates the general pattern of returns to acquirers. These findings are not accidental. Investor reactions are powerful forecasts of the future based on previous expectations and the new information given by the company about the economic wisdom of the transaction. Acquirers that truly deliver and show evidence of their ability to make good on their promises do extremely well over time; acquirers that deliver on the negative expectations do extremely poorly. The differences are enormous.

Shareholder returns to acquirers

Looking back, the initial market reactions of both the persistent positive and persistent negative portfolios (8.0% and −9.0%, respectively) are very close to the announcement returns for overall initial positive and negative portfolios. The subsequent performance of the persistent performers is largely a function of acquirers confirming the initial perceptions of investors.

This leads us to ask a question fundamental to the rest of this book: Based on this data, would you rather start with a positive investor reaction or a negative one? (See the sidebar, “Shareholder Returns from M&A” for additional findings.)

The Acquisition Game

How can this be? Everyone knows by now you shouldn’t pay “too much” for an acquisition, that acquisitions need to make “strategic sense,” and that corporate cultures need to be “managed carefully.” But do these nostrums have any practical value? What do they mean, anyway? What does it really mean to pay a premium? More fundamentally, what even is “synergy”?

Here’s how it typically goes in M&A: A company decides to grow through an acquisition, not because it has a well-developed growth thesis but because the stock market is riding high and lots of other companies in the sector are announcing deals and getting attention. Or perhaps an adviser puts on a convincing presentation that the would-be acquirer buys because organic growth is leveling off, and the CEO becomes enamored of the deal.

Shareholder Returns from M&A

- Acquisition premiums matter. The average premium paid for targets across the whole sample was 30.1 percent, with an average premium of 32.2 percent paid by the initially negative portfolio and 26.9 percent paid by the initially positive portfolio. Not surprisingly, the average premium paid by the persistently negative performers was 33.8 percent whereas the persistently positive performers paid an average premium of only 26.6 percent. The difference in premiums is even more striking for all-cash and all-stock deals for the persistently negative versus the persistently positive portfolios (36.6% vs. 27.6% for all-cash deals and 32.8% vs. 22.5% for all-stock deals, respectively).

- Cash deals outperform stock deals by a lot. All-cash deals (20% of deals) markedly outperformed all-stock deals (36% of deals). At announcement, the returns for all-cash deals beat all-stock deals by +4.7 percent (+1.8% vs. −2.9%, respectively). Moreover, 57 percent of cash deals receive positive market reactions versus only 35 percent for stock deals, and the performance gap only widened over the course of a year to 9.5 percent as cash deals beat their peers by +3.8 percent while stock deals lagged their peers by −5.7 percent. This finding reaffirms the widely reported result on the underperformance of stock deals. The contrast is also illustrated with 46 percent of stock deals in our sample receiving initial and persistent negative returns versus 27 percent of cash deals. Combo deals—a mix of cash and stock—yielded announcement returns of −2.1 percent (with only 36% receiving a positive reaction) and one-year returns of −1.9 percent with a similar persistence spread as the overall sample of 1,267 deals (see appendix A for additional details).

- Sellers are the biggest beneficiaries of M&A transactions. While buyers on average lost, shareholders of selling companies earned an average 20 percent peer-adjusted return from the week before deal announcement to the week after. That contrasts with the average announced premium of 30 percent because of negative market reactions for acquirers on stock and combo deals, which reduced the amount actually received by sellers.

- M&A transactions create value at the macroeconomic level. Mergers create value for the economy. We calculated a measure for both buyers and sellers based on the 11-day peer-adjusted dollar return, for both, around deal announcement. The average total shareholder value added (TSVA) is simply the sum of those dollar returns for buyers and sellers. While buyers lost on average $285M, sellers gained an average $469M for a TSVA of $184M for all deals. (The TSVA is $333M for all-cash deals and $11M for all-stock deals.) The TSVA has improved over our three periods from nearly zero in the first period to $424M in the last, again with the majority of those gains going to sellers.

We also calculated a TSVA percentage based on total market capitalization of buyers and sellers. In the aggregate, we find value creation (TSVA) of roughly +1.45 percent at announcement based on the combined changes in market capitalization. Cash deals yielded a combined return of +3.73 percent, while stock deals had a combined change of +0.07 percent—a large difference—and a return of +2.05 percent for combo deals.

When acquirers play the acquisition game, they enter a unique business gamble where they pay an up-front premium for some distribution of potential outcomes—the synergies. If acquirers do not fully understand the performance promises they are making up front, or do not have the capabilities to deliver on those promises, or if the synergies are illusory, they will have engineered failure right from the beginning—something investors can and do recognize right at announcement.

Let’s start with some simple examples that will illustrate the point.

Imagine there is an apartment you truly want to own on a lovely block of Greenwich Village in New York City. Sure, it’s expensive, but you really want it. You and all your friends agree that it is better to live there than where you live now. You’ll feel better. What’s more, the apartment is a fixer-upper, and you figure you can increase the $1M appraised value by at least 25 percent. Unfortunately, you are dealing with an unmotivated seller who is asking $1.5M for the apartment. But you have spent so much time searching for the right place, and this one is a perfect fit. (Besides, all of your friends have apartments so much nicer than the one in which you currently reside.)

Do you go ahead with the transaction price of $1.5M? It depends on whether feeling better about your apartment is worth $250,000 to you. Because even if you make the improvements you think are possible and even if they add 25 percent to the appraised value, you will have permanently sacrificed $250,000 right at the point of purchase.

Or suppose you just arrived in Las Vegas, a trip you have been planning for a long time. You have read all the books about the various casino games, and you are sure you will make a killing. On the way to the casino, an attractive hotel employee beckons you to a room to play a very special game. You are offered the following payoff distribution: A fair coin will be flipped where heads (H) = $20,000 and tails (T) = $0. It will cost you $9,000 to play the game. Thus,

You think for a moment and realize that according to the law of averages, if you could play this particular game 100 times, you could make a lot of money—$100,000. That is, you pay to play whether you win or lose, and you expect to win 50 times for a net gain of $100,000 [(50 × $20,000) − (100 × $9,000)]. On the other hand, you also realize you could be wiped out after just a couple of plays before the law of averages sets in.

The essential lesson here is that we have to be very clear about the distribution of payoffs before we pay the price to play the game.

These examples illustrate the acquisition game. The acquisition premium is paid up front and we know it with certainty. The actual post-merger integration (PMI) will yield some uncertain stream or distribution of realized payoffs or synergies sometime in the future. Executives need to consider the likelihood of different scenarios of these payoffs (the synergies), or they may actually know more about the payoffs in blackjack than for a given acquisition. Stripped to its essentials, then, an acquisition is a traditional capital budgeting problem. But it is a unique one for several reasons that executives and boards must appreciate.

First, acquirers pay everything up front—the full market value of the target’s shares plus a premium—before they even get to “touch the wheel.” There are no dry runs, no trial and error, and unlike other capital investments, like R&D—there is no way to stop or divert the funding, other than divesting. Most important, the cost-of-capital clock on all that capital starts ticking from the beginning. So, delays will be costly. There are no do-overs.

Second, when acquirers pay a premium, they are taking on an already existing performance problem and creating a brand new one—one that never existed, and no one ever expected for those already existing assets, people, and technologies. In other words, acquirers have two performance problems: 1) they must deliver all the profitable growth and performance the market already expects from both the acquirer and the target, and 2) meet the even higher targets implied by the acquisition premium. Achieving those new performance requirements typically requires an enhanced set of capabilities, and competitors will not sit idly by while acquirers attempt to generate synergies at their expense. Putting together two profitable, well-managed businesses does not magically create strategic gains because competitors are ever present, and customers may not value the new offers.

That yields a clear definition of measurable synergies: Performance gains over stand-alone expectations. Putting together the up-front premium with the brand new performance problem, we have a straightforward view of the value created for the acquirer, the net present value (NPV) for a transaction:

NPV = Present Value (Synergies) − Premium

That is, assuming you don’t ruin the businesses and can deliver all the stand-alone growth value already expected of the target (and your company), you create value only if you can achieve at least a cost-of-capital return on the premium. Executives paying a premium commit themselves to delivering more than the market expects from the current strategic plans of both companies.

Third, once acquirers begin intensive integration—so essential to generating the required synergies they have promised—they will have jacked up the costs of exiting and unwinding a failing deal. Closing a world HQ, merging IT systems, integrating sales forces, and reducing headcount is expensive and time-consuming to reverse. And in the process, acquirers may run the risk of taking their eyes off competitors or losing their ability to respond to changes in their competitive environment or evolving customer needs.

What’s more, not only can shareholders readily diversify on their own, without paying a premium, but paying a higher premium does not necessarily yield a higher return or more synergies—in other words, the payoffs are not a function of the size of the bet.

The characteristics of deals that make them unique, taken together, form the three parts of what Mark has called the “synergy trap.” Executives must do the hard work to avoid the following:

- Failure to understand the performance trajectory already priced into the shares of both stand-alone companies. The result: Acquirers often mistake “synergies” with performance improvements already expected by investors. Synergies are improvements over that base-case trajectory—savings or profitable growth that can only be achieved as a result of the deal (“if but for the deal”). Confusing synergies with that base case will haunt you and your employees throughout the entire process.

- Failure to consider synergies in both competitive and financial terms. If competitors can easily replicate the “advantages” of the combined company, then synergies are unlikely. They aren’t just advantages because you say it is so; your customers have to agree. Achieving synergies means competing more efficiently and through a more differentiated and defendable position. Moreover, synergies don’t come for free—there may be significant one-time costs and ongoing costs to achieve the benefits. We call this the “synergy-matching principle” because you have to match the benefits with the costs to achieve them. Those one-time and new ongoing costs are, in effect, additions to the premium.

- Failure to understand the performance promises built into paying an up-front premium. When you pay a premium, you are signing up for a new performance challenge that didn’t exist before and no one expected—over already existing expectations. Acquirers must fully understand both the promises they are making and the capabilities, resources, and discipline required to realize those new required performance improvements. Remember, the cost-of-capital clock is ticking on all of that new capital from Day 1, whether or not you are ready to deliver.

The result is simple from a shareholder-value perspective. Think of it like an economic balance sheet. When you make a bid for the equity of a target, you will be issuing cash or shares to the shareholders of that company. If you issue cash or shares in an amount greater than the economic or present value of the assets under your ownership (without fully realizing the synergies), you have merely transferred value from your shareholders to the shareholders of the target—right from the beginning. This is how the economic balance sheet of your company stays balanced. It is the NPV of the acquisition decision—the expected present value of the benefits less the premium paid—that markets attempt to assess. That’s what it means when sophisticated capitalists bid down the price of an acquirer while the price of the target goes up from the offer of a premium.

Because they fail to understand the traps and anticipate those complexities, acquiring companies tend to predictably overpay—by a lot. Faulty analysis is often baked into the calculations that companies use to evaluate the deal. The advisers make it look so easy. They price the target company as a stand-alone. Then they add in the form the synergies will take by putting the two companies together: a boost in revenue growth, lower cost of capital, efficiency gains through scale—and voilà! Out comes the right price and off they go to integrate the companies.

But so many errors can creep into an acquirer’s M&A process, if they even have one, that oftentimes those synergies don’t exist or are greatly exaggerated in a valuation model, on a deal that may not have been the right target from the get-go. The result: Without a disciplined process, target valuations converge to how other acquisitions are getting priced. And that’s where the potential for value destruction begins.

The Solution

But here’s the thing: It isn’t that all acquisitions are bad, it’s that poorly conceived or executed acquisitions are bad. Executives can generate valuable growth through significant investments in M&A. But it does mean that executives must understand why acquisitions are unique and risky—and begin to treat capital as luxurious. CEOs must answer the question whether they and their senior teams have done the proper strategic homework, careful valuation with specific synergies, and post-deal planning that might earn them the right to spend that luxurious capital.

Winning the acquisition game requires a lot of work and informed discipline—with myriad complexities ranging from considering valuation issues, competitor reactions, employee expectations and uncertainty, investor and employee communications through to the design of the new organization. This is the root of why so many companies fail and why investors are so skeptical.

There is an art and science to getting M&A right. We plan to guide you through how to develop and execute an acquisition strategy that avoids the pitfalls that so many companies fall into, how to properly communicate the performance promises you are making when you pay a premium, how to realize those promised synergies, how to manage change and build a new culture, and how to create and sustain long-term shareholder value.

We’ve learned the answers to these questions the hard way—through research, innovation, and hard-won experience. Between us, we have over 50 years of experience with M&A, from multi-billion-dollar acquisitions to carve-outs and everything in between. We’ve been behind the scenes helping companies with crafting their M&A strategy, conducting diligence that tests the deal thesis, preparing for Announcement Day, and assisting with merger integration.

We wrote this book to help companies that are planning to use M&A as part of their growth strategy. It should help executives prepare and understand the intricacies of incorporating M&A into strategy, from developing a list of their most important potential deals to understanding the overall process and how to make success more likely—and deliver on the promises they make to their shareholders, employees, and customers. At the same time, it’s also for the working managers on whose shoulders falls the responsibility of conducting diligence and synergy planning, and making the merger work and deliver on the promised results—oftentimes even when they first learn about it on Announcement Day.

The Synergy Solution offers an integrated view of the issues surrounding M&A. It provides background to those considering M&A, teaching which issues they have to consider, how to analyze them, and how to execute effectively. It also shows those who have already started the process of M&A how to maximize their chance of success.

The following five fundamental premises have guided our thinking and should be the touchstones for senior management and boards when considering M&A as a component of a successful growth strategy. They will become more salient as we proceed through our journey.

- Successful acquisitions must both enable a company to beat competitors and reward investors.

- Successful corporate growth processes must enable a company to find good opportunities and avoid bad ones at the same time.

- Prepared acquirers (what we call “always on” companies) are not necessarily active acquirers—they can be patient because they know what they want.

- A good PMI will not save a bad deal, but a bad PMI can ruin a good one (i.e., strategically sound and realistically priced).

- Investors are smart and vigilant—that is, they can smell a poorly considered transaction right from announcement, and they will track results.

The Chapters

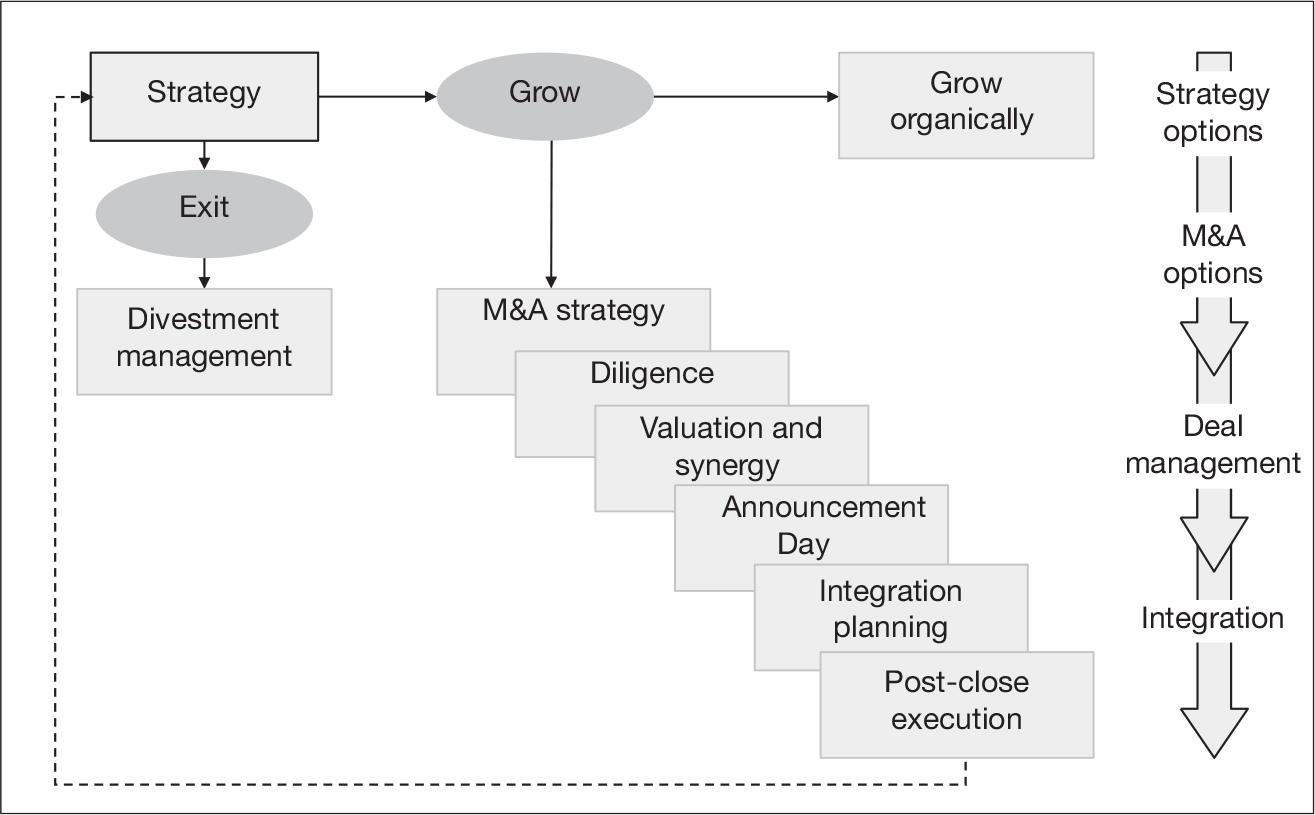

The Synergy Solution proposes a unique cascade that takes the reader from pre-announcement strategy through understanding the acquisition premium, how to understand the performance promises made to investors, Announcement Day, and on to how to execute on the promises made to investors. (See figure 1-2.)

In other words, The Synergy Solution encompasses the entirety of the process in a comprehensive methodology appropriate for multiple levels of the firm. It will give you the tools to distinguish smart acquisitions from poorly considered ones, effectively communicate the economics to multiple stakeholders, and execute and ultimately deliver value.

The M&A cascade

We’ve organized the book around a series of questions that speak to each stage of the process, beginning with “Am I a Prepared Acquirer?,” the subject of chapter 2. It argues that most companies are reactive—responding to deals that appear before them—rather than proactively developing a priority watch list of their most important deals. The chapter lays out the case for why and how companies should and can prepare, including strategy and governance, and helps set up the logic for the rest of the book.

Chapter 3 asks, “Does It Makes Sense?,” exploring three kinds of due diligence: financial, commercial, and operational. While diligence often is treated as a necessary evil—or even as a mere review of audited financials—this chapter argues that a robust, insight-driven diligence process that’s rooted in your investment thesis will not only help you value the potential deal and identify potential integration hurdles, but can also suggest when to walk away.

Chapter 4 is all about the implications of the valuation and asks, “How Much Do I Need?” It shows a theoretically correct and direct approach to valuation and synergy that’s based on the well-accepted concept of economic value added (EVA) to first examine both the acquirer and target as stand-alone companies—to understand the performance trajectory already expected by investors. We then use the new capital allocated in the form of paying the full market value of the target’s shares (while assuming the debt) plus the acquisition premium, to show the annual improvements being promised by the acquirer, and how the premium translates into required improvements in after-tax net operating profit—the synergies; calculations that investors can and will do themselves.

Chapter 5 asks, “Will They Have Reason to Cheer?” on Announcement Day. Investor reactions set a tone that will impact all stakeholders. When material M&A transactions are brought to the market, they are often professionally staged and treated as a celebration for the senior executives of both the acquirer and target. But acquirers must treat Announcement Day less like a celebration and, instead, like a carefully orchestrated presentation, one with the clearly established goal of communicating the deal’s value to all stakeholders.

Chapters 6 and 7 form a pair to address pre-close planning. They focus on how to avoid the mess that can come from poor planning, and how to capitalize on the deal momentum to rally the troops, energize customers, and lay the foundation for results to report to investors. Chapter 6, “How Will I Deliver on My Vision and Promises? Part I” shows how to realize the promise of your deal strategy during pre-close integration management. It focuses especially on the role of the Integration Management Office (IMO), a temporary structure that manages integration, both top down and bottom up.

Chapter 7, “How Will I Deliver on My Vision and Promises? Part II” examines the workstreams at the heart of integration and how to get ready for Day 1. Here, we focus on the cross-functional workstreams that are typical of the vast majority of pre-Day 1 integration structures and overseen by the IMO: organization design, synergy planning, communications and employee experience, and Day 1 readiness.12

Chapter 8 asks, “Will My Dreams Become Reality?” and focuses on the core job of the post-close execution team: to transition from the pre-close workstreams with the aim of getting the integrated businesses to business as usual as quickly as possible and well on their way to realizing synergy targets. The longer post-close execution takes, the less likely management is able to deliver on the value detailed in the original deal thesis. In an unforgiving market, this can lead not only to adjustments in earnings expectations, but also to management losing the ability to achieve the financial results achieved prior to close.

Chapter 9, “Can the Board Avoid the Synergy Trap?” offers several tools that can help boards spot those deals that are likely to result in negative market reactions. It also provides the board with a common framework that will drive more informed discussions about potential material deals. The tools will help close the gap between what management believes and what investors are likely to perceive before the market does. Without those tools, the board will be unable to answer the fundamental question: How will this transaction affect our share price and why?

Finally, chapter 10, “Getting M&A Right,” brings the book to a close by reviewing the M&A cascade. If you make a mistake in M&A, you’ll not only see a drop in your share price on Announcement Day, but you’ll be stuck with the acquisition for years of pain before you grudgingly divest. By working through The Synergy Solution, you can avoid that ugly fate and transform into being a prepared acquirer who can realize the value of M&A done right.