CHAPTER 8

Will My Dreams Become Reality?

Post-Close Execution

Day 1 is an exciting milestone, but, operationally, it should be relatively quiet, involving communication with employees and customers, ensuring regulatory hurdles have been met, and that bank accounts are ready to go. But once the deal has closed and Day 1 celebrations have come and gone, the road to integration and the future state of the new firm begins. Buckle up, because all of this will be under public scrutiny as you begin to report results.1

Post-close execution must receive the same level of management attention that Announcement Day and pre-close planning did. The key to post-close success is maintaining momentum. Thousands of decisions have already been made before Day 1, but they have not been tested and implemented by the new organization. This chapter focuses on how to improve the odds of successful execution of the deal thesis and the fulfillment of all of the pre-close planning without stumbling—and how to do it quickly and efficiently. But first, a word on the risks.

New significant risks begin to enter into the deal after Day 1. Issues such as overlooked interdependencies or change programs without adequate leadership authority can build with a slow drip until they reach the point where senior management takes notice. Critical employees can leave, taking their legacy knowledge with them and causing damage to the underlying businesses—even if some synergies are realized. The result can lead to not only loss of confidence from investors but also loss of vital relationships with customers, employees, and suppliers.

Post-close is also the period when many acquirers also begin to transition the attention of executives who saw a deal through from inception back to their operating roles. Executives will begin the handoff to managers who will be focused on the integration program. This shift in focus can present real challenges to preserving the teams’ attention on execution.

The biggest mistake that we’ve seen is that acquiring leaders move their attention away from the deal, sometimes even putting some of the integration back into the hands of the managers from the target—asking them, for instance, to change their processes, or to achieve synergies that they aren’t invested in, or to deal alone with change management issues. We can assure you that it is unlikely the target has the same goals as the acquirer, and its managers will prefer to keep operating the way they did pre-acquisition.

Another pressing issue is having no clear definition of the end state—that is, not knowing when the transition is complete, when the two organizations are truly operating in the marketplace as one combined entity.

Other roadblocks exist as well. Among them are a failure to have a clear understanding of the synergy projects in play, leading to a subsequent failure to properly track synergies. Frankly, everyone is tired from the sprint to Day 1, and that fatigue can lead to bad decisions, including disbanding the IMO too soon. The discipline of the IMO will be necessary post-close, when the IMO shifts to a different structure.

What are the signs and symptoms of “the wheels coming off a deal”? It can be a long list, but telltale signs include when integral managers, feeling disaffected and uninvolved, start to leave; when employee satisfaction and morale suffer because employees don’t feel like they belong and are not being appropriately integrated; when dissatisfied customers leave for competitors because their needs haven’t been met or promises have been unfulfilled; and when deal goals lose priority, as those who are responsible for execution feel removed from the planning and find the goals too challenging to meet. All of this adds up to a failure of financial performance, when the deal falls well short, 12–18 months in, of the synergies that were announced.

The fact is, the longer post-close execution takes, the less likely management will be able to deliver on the value detailed in the original deal thesis and promised to shareholders and customers. In an unforgiving market this can lead not only to adjustments in earnings expectations but also to management losing the ability to achieve the financial results expected for both companies before the deal. Moreover, as post-close integration activities continue, time and money the business could have otherwise used for growth continue to get consumed, taking attention from other opportunities and limiting follow-on acquisitions and growth.

The majority of post-close execution activities should occur within a year of close—certainly no longer than 18 months. Much longer than that, and interest will surely wain. Inability to execute major integration tasks within the first year not only reduces deal value as the present value of forecasted synergies decreases but also means that tracking operational gains becomes more complex. Slow execution also complicates change management as manager and employee behaviors calcify and they start treating the transition way of doing business as “the new normal.”

The first step in successful post-close integration, then, is to ensure there is a dedicated transition team—typically the IMO—that focuses on integration activities with a clear group of leaders and trusted functional and business leads who are solely focused on integration and transitions and empowered with decision authority.

The core post-close task is to drive the new company toward fulfilling the initial deal thesis and implementing the plans and decisions made before Day 1. Post-close execution should therefore center on getting the integrated business and its new operating model to business as usual as quickly as possible. Together, there are five major transitions to manage:

- From the IMO to business as usual

- From organization design to talent selection and workforce transition

- From synergy planning to synergy tracking and reporting

- From the clean room to the customer experience and growth

- From the employee experience to change management and culture

These are addressed individually in the sections below, which focus on the details—the substance—of how to track the necessary transitions that lead to superb post-close execution.

Transition 1: From the Integration Management Office to Business as Usual

The IMO and the structure it governs don’t end on Day 1, but they do go through a definite shift. Sprinting to Day 1, the IMO managed and oversaw the workstreams, paying particular attention to interdependencies and priorities that were bigger than any one functional area. After Day 1, the IMO begins to graduate functions into business as usual. While the pre-close IMO focused on defining the end state and creating plans and synergy projects, the post-close IMO becomes all about execution, transition, and orienting structures to achieve the promised goals.

Because Day 1 can bring a lull in efforts—caused by fatigue from the sprint combined with the feeling that Day 1 constitutes a finish line of sorts—the IMO must preserve momentum so the integration doesn’t fall off the rails as people get distracted. Remember, this is just the beginning of executing on all of the pre-close planning. Short-term solutions or workarounds that got you through an issue-free Day 1 now must be confronted as you transition from the IMO structure to business as usual.

Post-close, integration planning will confront the realities of execution. While the idea of “realizing the value of the deal thesis” is an elegant rule of thumb, one of the major aspects of the post-Day 1 IMO, practically speaking, is managing ongoing interdependencies across the workplans and the day-to-day overlap among workstreams, making sure plans and milestones are on track and that the integration machine is running smoothly. It’s only when the integration work no longer requires this extra level of coordination that it is time for a workstream to graduate and move to business as usual.

What does “business as usual” actually mean? For our purposes, it refers to the typical ways that functions work together and will continue to work together into the future without the additional coordination across workstreams provided by a body like the IMO.

The objectives of graduation to business as usual are threefold:

- Allow teams to transition execution to business units and exit from participation in regular IMO meeting cadence

- Ensure that a clear path exists for workstreams to complete all integration objectives and achieve synergy targets

- Signify to executive sponsors and SteerCo that a workstream no longer requires active coordination and efforts of the IMO

A common mistake is to tie achieving business as usual status for a workstream to achieving a certain amount of synergy realization. For example, IT or finance may have realized 100 percent of their synergies but may still be held back from graduating because other workstreams are still dependent on their other integration activities. IT and finance may remain on the critical path for other workstreams to realize their synergies or operational integration requirements. Graduation to business as usual must truly be about not needing to coordinate integration activities any longer.

Once a workstream does graduate, the IMO will no longer oversee program management for the workstream. This means attendance at IMO meetings is no longer required—the purpose of these meetings, remember, was input into coordination efforts and status reporting on milestones and overall workplans. After their transition to business as usual, integration workstreams will no longer exist as their projects and activities are added to the existing portfolio of projects and initiatives of the ongoing businesses or functions. Budgets are integrated into the normal annual operating planning and budgeting process. And project managers become responsible for supporting documentation and workstream deliverables.

As a consequence of graduation, workstream leaders will assume responsibility for remaining integration-related commitments, including staffing of resources necessary to execute on plans.

Workstreams will still need to update integration readiness projects in a central planning tool for tracking and reporting, while tracking of synergy capture and integration spend will be ongoing, led by the IMO and FP&A.

Migration rates from IMO to business as usual will differ by function. Often back office operations like HR, IT, and finance require the most attention from the IMO since they are the “long poles in the tent”—the initiatives that take the longest to realize and that other functions depend on. Integration of the acquirer and target may begin with heterogenous systems in those areas (IT, HR, and finance) that must be normalized as the new organization moves to business as usual, a process that can typically take more than a year. In a carve-out, transition to business as usual happens when the TSAs are fulfilled and exited. HSR-mandated divestments also must be resolved before business as usual is reached.

As a useful example, consider the synergy cross-functional workstream. It will formally transition to business as usual when the individual workstreams have approved targets and bottom-up plans have been incorporated into the functional or business financial budget (which will now have a lower spend or higher revenue expectations). Tracking the results ultimately becomes the job of FP&A—as would normally be the case for tracking business performance. For some companies, the synergy team will dissolve when the company has met or exceeded the run-rate commitments made at the deal announcement. Other companies have used markers such as when synergy realization is well underway and trending at or above expectations before transitioning to FP&A.

Until that formal transition to FP&A, the IMO must make sure synergies are being documented and tracked, otherwise a business or functional unit can game the system for their first year so the IMO will stop bothering them. Without established synergy targets and a mechanism for validating achievement, the business unit might sandbag and give the IMO synergy numbers it can easily beat, counting it as synergy when it really isn’t.

Knowing when the IMO itself will be fully disbanded is part of the integration end-state vision up front. Defining what “done” means is an integral part of planning and will vary from integration to integration and the complexities of the workstreams. But the executive team needs to know when they’ve arrived for each function and business. In the ideal, the end state is defined as when the two companies are operating in the market as one and the value of the deal thesis is fully realized.

Because workstreams will roll off over time, the IMO structure will flex, shrinking in size and diminishing in importance—either by reducing the number of members, reducing the number and frequency of meetings, or by allowing workstreams to leave the governance structure. The cadence of meetings and executive report-outs will become solely related to synergy capture rather than to procedural integration. The IMO’s end is typically indicated by the IMO leader taking another role, and many team members resuming pre-IMO business roles or finding new positions. There is often a less senior person from the IMO team who assumes controls to address the final close-out duties.

But remember that until the integration is done, the IMO in some form is still intact. (See the sidebar, “Illustrative Business as Usual Graduation Process.”)

Transition 2: From Organization Design to Talent Selection and Workforce Transition

Following organization design and role decisions, it’s time to choose the talent that will help lead and execute the new company’s plans and transition the rest of the workforce.

Talent selection

Talent selection—led by the organization design team—is more than just about picking the right talent. It’s fundamentally about who remains and who departs from either company, and who gets which role. Further, it’s also about the faithful application of agreed and prioritized selection criteria—relevant experience; skills; compensation (cost); performance ratings; geographic location; diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) targets; and so on. By Day 1, L0 through L2 (or possibly L3) leaders have been chosen at the top of the house and announced—important signals for the future direction of the combined company. The job now is to select, notify, and transition L3 or L4 leaders and below—a much larger workforce.

Illustrative Business as Usual Graduation Process

- Core IMO identifies workstreams that are candidates for graduation. Workstreams can reach out to IMO if they feel they are ready.

- IMO works with eligible workstreams to complete the documents required for graduation.

- IMO and eligible workstreams participate in a combined review of required documents and seek approval from the respective workstream executive sponsor.

- Upon approval, workstream leadership acknowledges full responsibility for the integration and workplan as it pertains to their organization.

Now is the time to execute on whichever option you chose during the pre-close planning process described in chapter 7: option 1 (where each selected leader designs their organization and roles and then selects their people, layer by layer) or option 2 (typically L3 leaders design their structure and roles from the top all the way down to the ground, and talent selection follows). Either approach will be guided by the synergy targets for each impacted function or business, where it is much easier to achieve synergy targets at the more expensive top of the house (L1–L4) than digging for savings deeper in the organization.

Whichever option you chose, though, the task now is to match the open positions to be filled to the pool of candidates—the candidate slate. The organization design and HR teams must ensure that the business leaders who are selecting talent are familiar with agreed criteria and that they apply those criteria consistently (and that the right people are considered). There will almost always be tension between fit, criteria, and cost in either option.

Option 1 can offer leaders on both sides the opportunity to give input on talent, which can be priceless given their historical knowledge. That said, this option can be influenced by the relationships that leaders have with candidates. Option 1 is prone to “hallway campaigning” because it is done layer by layer. This can lead to biased outcomes because it becomes harder, perhaps unintentionally, to apply the agreed talent criteria clearly and fairly. We all have coworkers we regard highly enough to imagine they can do virtually any job even if they don’t have the “right” background.

But option 1 has advantages too. Namely, the cost of each layer can be sanity checked to ensure that it is tracking to synergy targets before proceeding to the next layer. Problems arise because there can be the temptation to keep higher-priced talent (often the most productive) that leaders believe they just can’t live without, but then cuts must be found in subsequent layers—and that can lead to another case of “death by a thousand cuts.”

Let’s play this out: Mark is chosen as an L2 leader, a divisional executive vice president, and one of the direct reports he chooses is Ami. Mark notifies Ami and installs her, then Ami designs roles and picks her people and notifies and installs them. They subsequently choose their own teams, and so on. If leaders at the top are not aligned with their synergy targets, they will push the savings burden down to the next layer and the next to the bottom of the house. As it gets harder to find savings deeper in the organization, they may have to go back and go through the process again—sometimes several times. When that happens, leaders can either go back and make difficult choices they didn’t make the first time or give up on the synergy goal, which is not uncommon (this is an example of leakage we discussed in chapter 7). And since the talent has already been informed, it can be painful and difficult to undo.

Option 2 allows a more data-driven approach for talent selection that’s overseen typically by L3 leaders along with their HR business partners all the way to the bottom-most layer of the organization. An advantage here is that it can facilitate the fair, and strict, application of the agreed-upon criteria to arrive at selection decisions across the enterprise, not just department by department. The design phase already considered the average cost of a role, but the selection phase now involves the specific cost of individual talent. It’s possible that such a straightforward application could result in sub-optimal choices or one that’s too costly because, for example, the highest producers are often the most expensive. This means that in the end the most expensive people might be chosen because cost was prioritized last. On the other hand, the new organization risks being without its best talent because it prioritized cost over something else—resulting not in a cost issue but a talent issue (which may be fine if the pool consists of younger high-potential talent who can grow with the role).

More tension arises when leaders don’t want to readily accept the results of the strict application of criteria. Leaders may feel that not only did they not design their organization, but they also couldn’t pick their best people. Although option 2 has less risk of unfairness or inconsistencies overall, people might feel resentful or unhappy with what they feel stuck with. The synergy target has been met, but they didn’t get the team they would have chosen. If upper-level management is unhappy with the results, or if lower-level managers revolt, adjustments may be necessary. The criteria can be revisited in the event of not meeting the synergy target. If lower-level managers are unhappy, the organization can help them be successful with the team they have—which might mean longer transition times, training programs, or more leadership time.

Regardless of which approach is used, it must include legal and synergy team reviews. Legal is looking for consistent application of the criteria with no unfairness or bias. The synergy team is looking to confirm that leaders didn’t deviate—intentionally or otherwise—from the approved synergy estimates and goals. Legal and synergy teams are often in the unenviable position of being the enforcer of the rules.

A review of the entire workforce can provide a chance to understand where processes may have created inequities (e.g., through unconscious bias) and to resolve or to reinvent those processes to foster long-term DEI goals. Day 1 can offer a time for the new organization to be transparent about where and how each company has had challenges, and to proactively address those inequities in the selection decisions. At the very minimum, redesigning the workforce should not unravel any progress either company made and should—looking forward—create career paths consistent with larger DEI goals.

Workforce transition

There are two major themes in workforce transition. First is the notification of all employees, as well as regulatory bodies, works councils, unions, and so forth, on the nature of how they will be impacted. Most countries will have their own employee notification requirements for plant closings and layoffs that have to be followed, such as the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act in the United States. Notification includes presenting employees who are staying (in new roles) with offers, presenting those who are needed short term with retention agreements, and presenting employees who are leaving with an exit plan and outplacement services. It is also important that employees who are not impacted understand the major organizational changes that are going on around them.

Second is the knowledge transfer that must happen for the smooth operation of the business as employees move into their new roles. Some employees will possess such valuable knowledge that they might need financial incentives beyond recognition and praise of their value, even to be simply “on call” during transitions. But the total number of employees who receive such retention bonuses should be minimal.

Other major considerations for orchestrating an orderly workforce transition include questions of timing, logistics, and sequencing—again, on 30-, 60-, and 90-day horizons. One important decision is which functions should transition at the same time and which should not. The organization design team can assess the relationships, documents, major account changes, and shifting technology changes that are coming and how they will affect different populations. For example, the sales force might be learning a whole new CRM on top of a new customer base and new metrics for accounts, as well as forming new relationships internally with support people who are also learning new things. Questions of sequencing revolve around the right amount of time and support to minimize disruption to the customer and stress for the employee.

As a consequence, workforce transition looks different function by function based on the level of risk attached to a poor transition. The most common approach is to quickly notify the enabling functions and realign employees as soon as possible before transitioning customer-facing people. On Day 1 it can be unclear who owns the major customer relationships, because that knowledge resided in the clean room planning. Companies typically view their customer relationships as competitively sensitive as well as their top talent, so leaders need to fully absorb the customer portfolio and sales relationships before making important decisions.

It is common to know how the back office–enabling functions will be impacted because pre-Day 1 planning included decisions on outsourcing, shared services centers, and IT system choices. That said, these changes may need 12–18 months to fully implement, which would mean retaining a substantial portion of those supporting people (e.g., systems administrators for payroll) for the duration of time that systems are being retired.

Timing, logistics, and sequencing are also important factors in knowledge transfer. With rapid notification and quick exits, vital knowledge that comes through years of experience can walk out the door. If an exiting employee wants to help, retaining them may require a short stay bonus of 30 days or more. Bonuses can be predicated on the successful transfer of knowledge, introductions to key relationships, or transmitting important documents as enumerated in the transition contract or retention agreement.

For instance, if Ellen gets picked to stay and Michael doesn’t, knowledge transfer planning should ensure that normal operations are not negatively impacted when Michael steps back and Ellen steps forward. Conversations that prompt self-reflection should account for the knowledge, relationships, documentation—the history of Michael’s engagement with the job and the information Ellen needs to continue to seamlessly serve the client, internally or externally (what we called the service delivery model in chapter 6). The aim is to create consistent if not elevated service delivery.

This process can be burdensome to the workforce, so it’s necessary to also account for the extra time and effort that the transition creates. This time might be tumultuous for an employee’s customers, while at the same time the employee is losing their finance or HR business partner and engaging with someone who is effectively a stranger and also unfamiliar with the new processes (with no bond of trust or shared history)—and that can be overwhelming for some talent. The workforce transition team must manage the sequence and timing of those changes.

The organization design team will also need to assess which functions can go faster than others. Ensuring that transitions happen in a way that’s least disruptive for employees and customers is vital. Of course, there are times when a culture is so broken and so toxic that disruption may be welcomed as an immediate fix, but this is rare. A more normal window for exits might be two weeks for many back office employees; customer-facing functions that are being redeployed but not exited could span a couple of months. But, again, the main message here is that both the workforce transition and knowledge transfer must be as thoughtfully sequenced as the rest of the acquisition has been.

Transition 3: From Synergy Planning to Synergy Tracking and Reporting

Pre-Day 1, the synergy team pushed the workstreams to develop initiatives and workplans, with a roadmap of milestones for each initiative. These plans should aim to achieve at least the cost or revenue synergy targets they were assigned. SteerCo has approved the plans, and they have been built into executive plans and goals with actual project codes attached to them. That was the easy part. There is a long way to go.

Now, the clean rooms are open, data is readily available, and the two companies can operate as one. The new company must begin to cultivate investor confidence in the deal because the acquirer has just formally purchased the target’s shares at a premium. The synergy plans, both labor and non-labor, must be revisited and confirmed in the light of day by the synergy team and the workstreams and immediately assessed for additional initiatives in each function that might be possible now that the new management team is in place.

More important, the IMO along with the synergy team will kick off an aggressive financial reporting and tracking process, designed and approved prior to Day 1, that will ensure that claimed synergies are auditable and directly attributable to the initiatives and workplans that will generate those synergies. Real synergies are discrete line items that will ultimately impact the P&L. They must be distinct from the operating plans already in place for both companies (“if but for the deal”), and the claim that they have been achieved must be able to withstand challenges that they are indeed real.

In our experience, acquirers will benefit from a tracking cadence—preferably weekly—that keeps a hot spotlight on progress and celebrates achievements by “ringing the bell.” At Ecolab, they were able to ring the bell in the first week after Day 1 as they recognized more than $21M from procurement synergies. Although the cadence can flex over time, the functions have to prepare for the long haul until at least the announced run rate for their net synergies (gross financial improvements less incremental ongoing costs to achieve) has been reached.

Synergy plans and results that are not managed and tracked aggressively will likely go off plan. Business leaders will want to do the minimum to achieve targets that weren’t their idea in the first place—and that they may secretly believe are unrealistic even though they have delivered initiatives and plans to achieve them. They may be tempted to game the synergy targets by exceeding their operating plan (e.g., by not spending their budget in the short term and counting it as a synergy). People don’t fail to honor plans because they don’t understand. They fail to honor plans because doing so is hard. They may attempt workarounds so they can go back to the old ways of doing things. That’s why establishing a process to monitor plans and recognize achieved synergies is so important, as is communicating and emphasizing significant financial incentives for both meeting and exceeding synergy targets immediately following Day 1.

For example, when two large environmental services companies merged, the new company announced up to $70M in synergy achievement bonuses to top executives and nearly 700 employees if they could meet a synergy target EBIT run rate of $150M. They would also be well rewarded if they met the lower target announced to the street that would yield a range of 25 percent to 100 percent of the maximum award, as long as the one-time costs and ongoing costs to achieve the synergies did not rise above an agreed amount. Incentives like this matter inordinately.

As we discussed in chapter 7, the synergy program is made up of a portfolio of prioritized initiatives. Each of those initiatives has an owner and requires a workplan—a series of milestones based on the number of projects that will be required to accomplish the initiative and achieve associated net synergies. After Day 1, the IMO will need to integrate the synergy workplans and milestones with the end-state functional operational integration plans to highlight what synergies are dependent on general integration activities.

That may sound like a large, complex endeavor. It is.

Only the IMO, however, has the full line of sight of all workplans, and realizing synergies must be coordinated with the operational integration on which synergy plans are dependent. These include such milestones as the first combined quarterly close or consolidating real estate or facilities. Reaching these milestones leads to direct cost savings for the newly combined organization.

Ultimately, this is a critical prioritization exercise for the IMO because some synergies may have fewer dependencies yet offer higher value relative to those that are more complex and less valuable (and that will also take longer to realize). Further, sequencing synergy workplans and operational integration activities must be aligned with the new operating model and leadership priorities beyond those of the deal (e.g., ongoing priorities of the businesses), so changes in priorities will require SteerCo approval.

A successful synergy reporting and tracking program will have three reinforcing components:

- Financial reporting, which establishes the mechanism of tracking benefits and associated costs from each synergy initiative that is tagged to an internal cost center, department, or project code.

- Milestone tracking, which is driven by the IMO and tracks the project milestones for each initiative to ensure dates and dependencies are being met as planned and are on track.

- Leading indicators, which are KPIs developed based on the primary synergy drivers to proactively monitor their dependencies and provide a forward-looking (vs. reactive) approach to course correction. Leading indicators are an ongoing “health check” that raise an early warning signal that synergy initiatives are likely off track and will likely not reach their milestones. Large initiatives with big payoffs and several major milestones are the prime candidates for using leading indicators. Those initiatives typically take longer, are more complex, and may need ongoing monitoring to keep them on track.

Remember our favorite CEO, Chas Ferguson of Homeland Technologies? Well, Homeland went ahead with its acquisition of Affurr Industries. They had an issue-free Day 1 and are now implementing their synergy reporting and tracking program. Consolidating attendance and sponsorships at tradeshows and other events is an initiative where Homeland believes it can realize millions in run-rate cost savings with Affurr because both companies go to many of the same ones. Milestones for such an initiative would include determining which tradeshows they had in common and the allocated spend; agreeing on a strategy for combined tradeshow footprint and which shows or conferences offered the best opportunities to consolidate; negotiating new terms; and the sequence of consolidation. A leading indicator might be how many tradeshows out of the total to be consolidated have been negotiated successfully.

Or consider the merger of the cosmetics companies we highlighted in chapter 6. The target had outsourced its production of fragrances to four contract manufacturers. A major source of synergy was insourcing fragrance production using the acquirer’s facilities. Major milestones included reconfiguring the acquirer’s manufacturing facility, buying new equipment that mixes chemicals and fills containers, conducting pilot production runs, ramping up production and hiring additional labor, and rolling off the contract manufacturers. Leading indicators included getting the technical specifications for the new machines ready and placing the orders for the new machines (that would take at least six months to deliver), monitoring the progress of hiring and training new employees, and progress of rolling off the existing outsourcing arrangements.

This leaves us with financial reporting and tracking, which involves six major concepts: the baseline, the assigned synergy targets, the functional or business financial plans, the periodic forecast, the actuals, and analysis of variances to spotlight problems and reforecast in either direction.

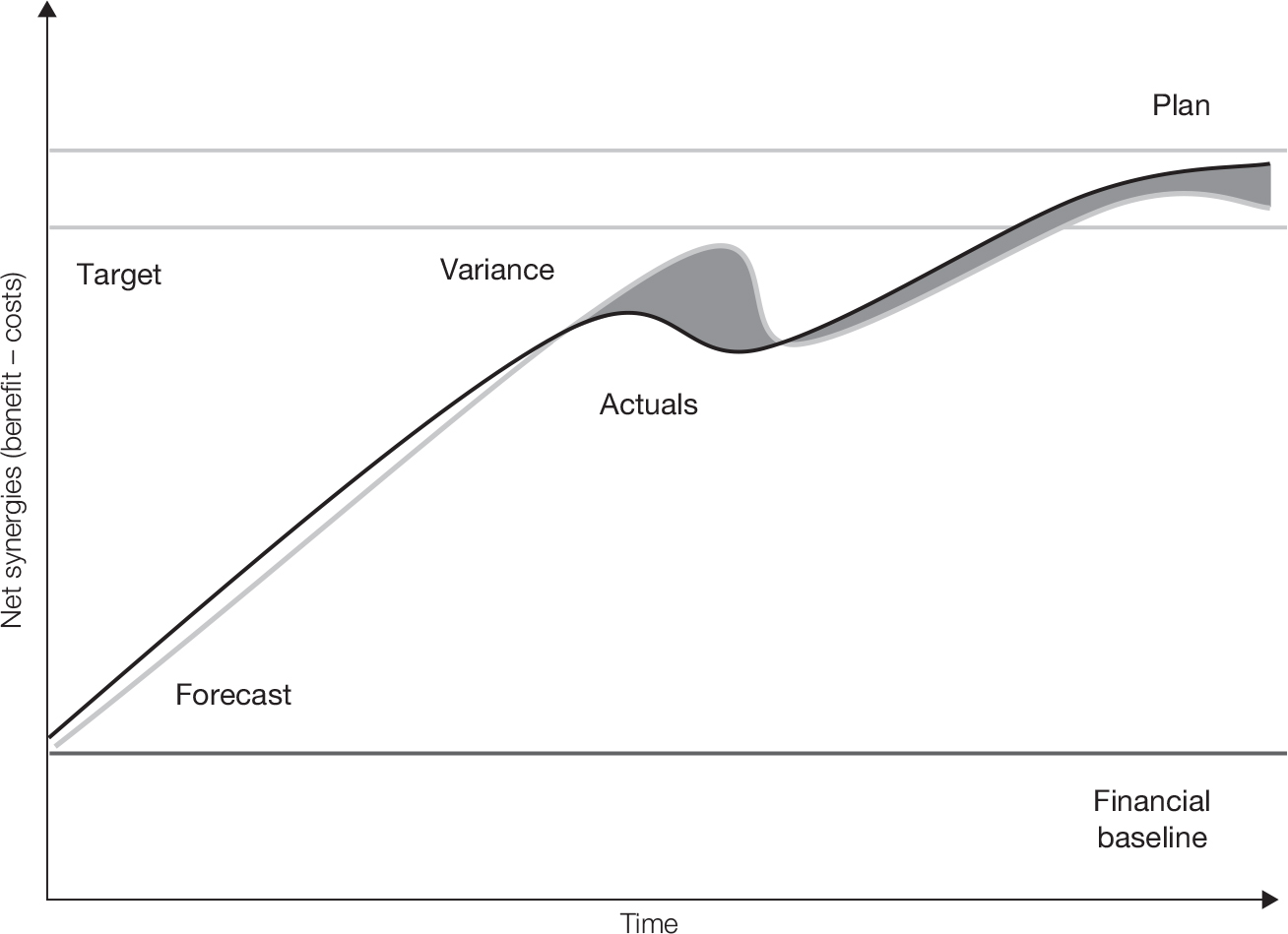

Figure 8-1 illustrates how these six items combine to form the financial reporting and tracking process. The starting point is the combined baseline of the forward plan without synergies. The assigned stretch targets are the minimum targets for the functions or businesses to achieve at the run rate. The plan is the bottom-up financial plan developed by the functions or businesses on Day 1; the plan must at least meet the targets but often will exceed the targets, especially with incentives. The forecast will equal the plan on Day 1 and will be re-forecasted every month or quarter based on the actuals—the recorded cost or revenue synergies that have been verified by FP&A. The variance between plan and forecast will need to be understood as the new forecast for both labor and non-labor synergies is refined for the next period.

Synergy financial reporting and tracking illustration

Note: For simplicity, we’ve held the baseline, target, and plan flat to focus on forecast, actuals, and variance on the way to achieving the plan.

It is this financial reporting and tracking process along with milestone tracking and leading indicators that the synergy team, the IMO, and senior management will use to manage the revenue and cost synergy programs and deliver the performance promises the acquirer has made.

In practice, the synergy team and the IMO have to instill a cadence of monthly actuals tracking; a quarterly evaluation and reforecast; a variance analysis against forecast and plan to understand why the company is exceeding or missing expectations; and executive reporting for the IMO, SteerCo, and the board. Initiative achievement will be aggregated across both labor and non-labor synergies. That means the IMO and synergy team work together to develop a standard approach and timeline that all will adhere to, on a regular cadence, to consolidate data on headcount and operational (cost and revenue) synergies.

Not having an agreed combined baseline in place prior to Day 1 is another invitation for mischief. Remember, the combined functional baseline presents the forward plan for costs and revenues that would have been in place without the merger. It is the starting point for the synergy tracking program because synergies will become part of the new budgets in business as usual for the combined company. Not pushing for that baseline before Day 1 will allow significant gaming as either side might pad their budget, from which synergies will be measured and rewarded.

Note a couple of important distinctions: one-time cost versus ongoing costs to achieve synergies, and the difference between run-rate synergies and P&L impact. One-time costs will typically be external advisers, lease breakage or vendor sunset fees, new equipment, or startup costs for new IT systems. Ongoing incremental cost would come from a growing sales force, for example, to drive growth synergies. Remember, net synergies are the gross improvements minus the ongoing costs to achieve them and result in increases in EBIT and NOPAT.

In chapter 4 we discussed the ramp up of synergies and assumed the full P&L impact for a given year. The “run rate of synergies” is a term often used and is the go-forward projected annualized savings, where the P&L impact is the actual total for the year (we equated run rate with P&L impact in chapter 4). Consider the following example of a $200,000 engineer who leaves in the middle of the year. The quarterly savings impact is illustrated as follows:

|

2020 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected synergy savings |

$0 |

$0 |

$50,000 |

$50,000 |

In this example, we have an expected run rate at the end of the year of $200,000 (4 × 50), but the P&L impact for the year is only $100,000 (the sum of the year’s improvements). The P&L impact will equal the run rate when synergy increases have leveled off and are in effect for a full year.

The synergy team will need to stay in place until there is sufficient confidence that the functions or businesses are well on track to meet or exceed the commitments that were communicated on Announcement Day and can be moved into the FP&A office as part of ongoing executive plans and budgets.

Transition 4: From the Clean Room to the Customer Experience and Growth

Although cost synergies represent the axis of value for lots of mergers, many deals also focus on growth. Valuable M&A revenue growth depends on preserving current revenue, achieving future growth expectations already in the stand-alone businesses’ financial goals, and then realizing additional revenue as a result of the strategic benefits of the deal—the revenue synergies. Revenue synergies will typically take longer to realize than cost synergies because they are subject to competitor and customer reactions and often depend on new sales systems, customer offers, and realignment of the sales forces.

These improvements are often facilitated by operating model changes that will make the combined company more customer focused—meaning that new growth depends on customers who believe they are being served better with higher-value offers by the combined company than they were before the deal.

An effective customer experience, in and out of M&A, can increase customer retention, spur higher and more frequent spend per customer, or lessen price sensitivity. It is predicated on delivering the right messages and products or services through the right channels at the right time at a price that customers are willing to pay. Any growth plans must be built around enhancing the customer experience.

The customer experience strategy and revenue growth planning began during the due diligence stage and were carried through the sign-to-close period in the clean room. Up-front considerations should have included drivers of customer purchasing behavior; improving current offers; how changes in offerings will impact customers and how they will likely respond; which customers are at the greatest risk of switching to a competitor and why; and what will be communicated to customers at announcement, during sign to close, on Day 1, and beyond.

Customer churn is a real danger during the merger. Customers leave for many reasons: disruption of services, lack of information, competitive behaviors between sales forces (often due to misaligned incentives), and predictable competitor reactions with aggressive customer communications of how bad the deal will be. Much of this churn is avoidable by evaluating the current customer experience by segment and channel, listening to what customers tell you, and then prioritizing customer experience improvement opportunities along the roadmap of touchpoints.

Engaging directly with your customers even before Day 1 is also a real option. For instance, when a semiconductor equipment manufacturer acquired a complementary cleaning business, the acquirer’s top customers previously had poor customer relations with the target’s sales force and leadership. Work to mitigate these issues prior to Day 1 included extensive meetings with customers to explain the acquisition, the new leadership team, and how their account teams would be impacted. Opening such a dialog before the deal closed (provided you’re not going to market as one combined company before it’s legal) allowed customers to air their concerns and the acquirer worked to mitigate revenue leakage and enable growth related to combining sales efforts immediately after close by explaining the enhanced benefits of the combination.

Even without such direct conversations, an enormous amount of data on customers and their behavior should be readily available. The combined sales force and data from all sales channels are extremely valuable assets in fully understanding customer needs. With enough of the right data, analytics and AI will allow the development of algorithms that have proved very valuable in offering more value to customers.

The sales force, specifically, is the connection point with customers. Their relationships and knowledge are the bedrock of revenue growth. Great salespeople understand why customers buy or don’t, when they buy, and how much they buy, as well as their satisfactions and dissatisfactions or unmet needs, what price they are willing to pay, and why they would switch—and even what they complain about over lunch or in the field. As such, members of the sales force must be ready to answer questions and be comfortable representing the voice of the customer to leadership as planning in the clean room transitions to executing on new growth opportunities.

From the clean room to growth opportunities

During sign to close, the clean room offered a sterile environment to assess the product and service portfolio across both companies, including overlapping customers, overlapping products and services, pricing, direct versus distributor approaches, and customer profitability and sales trajectories by customer and geographies—all to size and prioritize potential opportunities for driving revenue growth and profitability.

But let’s get back to basics. Revenue synergies are in fact just a special case of the general issues all companies confront when they evaluate and consider changes in their go-to-market strategy to improve their growth trajectory. Broadly speaking, improving go-to-market strategy boils down to either expanding how much of the addressable market can be served (beyond what we called “serviceable market” in chapter 3) or making better offers based on improving the customer experience, creating new offers, or a combination of those two that customers value.

Expanding the serviceable market starts with a focus on capture points or the moments that allow a business to get in front of the customer—the “at bats,” as it were. In financial services, for instance, the bank branch is a traditional capture point, a concrete place to attract depositors and offer new, relevant, valuable products or services. It’s where customers—even millennials—still prefer to show up and engage.2

Go-to-market strategy changes will often focus on “win themes” that focus on strengthening or expanding customer capture points (customer segments, geographies, channels) or addressing customer preferences you aren’t doing today (service, responsiveness, product quality) or offering bundles of existing products they really want and may create less price sensitivity because of the new benefits. Internally, that might mean redesigning sales incentives and sales teams, streamlining the sales process by offering faster pricing approvals, using better CRM, or using better sales systems from order and billing to delivery.

In M&A, the issues are no different, but they can certainly be more complex. Acquisitions bring with them an entire portfolio of new possibilities and opportunities—myriad new capture points and potential offerings that presumably were not available as separate companies. Company A might have stronger relationships at large accounts or better digital channels than Company B. Company B may have better geographic or international presence than Company A. Collectively, they have a portfolio of products or services that can be sold together, enabling a cross-sell of existing products, attractive new bundles, increased geographic presence, or brand-new products or services.

Let’s start with an organic growth example that would-be acquirers should appreciate: the successful transformation at IDEXX, a veterinary diagnostics and information management company. It’s a great illustration of a dramatic change in go-to-market strategy that involved a combination of cross-selling and new and better offers.

In 2013, Jay Mazelsky, leader of the North American Companion Animal Group at IDEXX, undertook a commercial model transformation to engage customers in a more compelling way. The transformation involved moving away from an emphasis on individual products to a market model built on solutions for companion animal veterinary clinics. That thesis kicked-off a multi-year, two-step go-to-market strategy transition to redefine how IDEXX touched customers.

The original commercial model had included a specialized sales force organized by product or service, and three large national distributors that touched the same veterinary customer base. That meant that diagnostic analyzers, laboratory services, and a rapid “SNAP” blood test for early diagnosis were separate product groups often sold by different salespeople. This segmented approach to customer engagement impeded cross-selling opportunities that could take advantage of multiple offerings to the same buyer, and salespeople had siloed career paths with little movement across product segments. It also meant there were insufficient IDEXX commercial resources who had the time or account coverage to build trusted adviser relationships with their customers. Any cross-selling that did occur required complex coordination.

IDEXX first restructured the commercial model into an account manager model with sales professionals owning accounts within an assigned territory instead of only selling individual products or services. That empowered customers to choose what was best—single products or an integrated solution—for their practice. It allowed, for example, diagnostics equipment sales to include discussions on laboratory support, SNAP tests, and a new offering that facilitated an integrated IDEXX software solution, including software that served as a data warehouse of all the historical test results for an individual animal patient.

Immediate impacts included an increased level of cross-product sales at points of sale; increased access to the veterinary clinic as the solution model allowed salespeople to serve as “strategic advisers” with a broader view of the business challenges facing clinics (which are essentially small businesses); and a more coordinated commercial operations framework that supported pricing, contracting, and service visits. This go-to-market strategy change—which effectively paired cross-selling with new and improved offers—was so successful in the first year that, for the second major step, IDEXX announced a distributor exit strategy at the end of 2014, replacing their distributor contacts with their own sales force. A larger commercial footprint with subject-matter experts in diagnostics resulted in dramatically faster topline growth, higher customer satisfaction scores, and ultimately a successful global rollout following the success of the new North American operating model.

Acquirers should have the same, or greater, opportunity than IDEXX to rethink their go-to-market strategies. In M&A deals, any analysis of growth synergies should reveal a long list of opportunities that will vary in degree of anticipated value, time to realize, complexity, and required investment. Prioritizing those opportunities must allow both quick wins to achieve early momentum and investment in longer-term projects like new innovative products to fully achieve the promise of the deal thesis.

Cross-selling—selling more of Company A’s products through Company B’s channels or relationships and vice versa—can provide quick wins by immediately expanding your serviceable market. It also supports the building of the new company’s brand. Leadership must clearly define these opportunities so the sales forces know who sells what to whom (so both companies aren’t calling on the same customer) and how to reach them—and be ready to announce a sales compensation plan that incentivizes cross-selling on Day 1.

Sales forces are typically excited about the opportunity to cross-sell, but many questions must be answered. Can Company A really sell Company B’s products? Are the procurement professionals the same for the individual products where they sell? Where there are overlapping sales forces at an account, will procurement be looking for discounts, just like you are trying to do with your suppliers for cost synergies post-Day 1? Can the companies reconcile different contracting and pricing terms? Can sales teams be sufficiently incentivized and trained to sell the other company’s products?

Whether it is pure cross-selling of existing products or considerations of new bundles or new products, inevitably the term that will emerge in revenue synergy discussions is “complementary”: “We have complementary sales forces” or “We have complementary products,” or “Customers will just love our bundled offers,” and so on. The bottom line is that capture points, or products or services, are not complementary just because leaders say they are. The new company must be able to better penetrate existing customers, reach more customers, and make offers that will delight them in new ways.

Examples of successful bundled offerings cleverly stitching together existing products and services abound. A simple but powerful bundled offer that many young families loved was when Amazon bought Quidsi (parent of Diapers.com) and offered a discount on diapers paired with a three-month free subscription for Amazon Prime—resulting in greater sales on both sides.

A more involved bundle was a deal that brought together transmissions and engines for heavy trucks. With some modification, the combination brought a powertrain with greater fuel efficiency than if customers purchased them separately or from other providers (any other transmission with a particular engine). Another example is when a chemical company acquired a data services firm, which allowed it to automate ordering so that customers no longer had to pay close attention to inventory, reducing the risk they would run out of key chemical components. Bundled offerings might unlock a customer segment that is less price sensitive and more focused on other benefits, such as when two airlines consolidated routes and offered better non-stop access to more destinations with more choices, which attracted the more lucrative business traveler.

Brand-new products will often have the longest lead time to value realization and will emerge from joint innovation where companies reimagine what the products or services can be beyond the bundling of offers. The two companies will already have their own innovation roadmaps at various stages of progress. Joint innovation should be led by examining a joint product development roadmap, combining intellectual property and technological capabilities, and exploring the “art of the possible” that would not have been available if not for the deal. That exercise will also aid leaders on a go-forward vision and decisions on which developing products to advance, which R&D efforts need to be rationalized, and what the future pipeline will be. Joint innovation can be as simple as creating a new application for a normal business process through new chemistries or technologies.

Valuable M&A revenue growth is challenging and complicated—but far from impossible.

New growth depends on customers who believe they are being served better with higher-value offers by the combined company than they were before the deal. Building on the work of the clean room team, relentlessly focusing on customer needs, and leveraging knowledge about customer behavior will form the solid foundation to create opportunities for growth that otherwise wouldn’t have existed. Cross-selling, new bundles, and new products can each provide pathways to real, sustained growth.

Growth at Ecolab

Ecolab and Nalco complementary products and services were the foundation of the combined company’s growth strategy, presenting opportunities for cross-selling, bundled offerings, and new products and services. Ecolab defined success as building and growing market momentum and increasing penetration in key accounts by leveraging existing channels and relationships.

With these and other growth objectives in mind, Ecolab held a three-day global sales conference in the first 10 days after close. The conference included the top 50 account leaders (from both companies) as well as key business leaders. The agenda included product demonstrations, cross-training, account leader meetings, and the development of action plans for each account, including jointly integrated value propositions.

Attendees discussed synergy and growth opportunities against the backdrop of the sales force reorganization, revised coverage models, and the drawing of new territories and responsibilities. These discussions revealed new opportunities to expand the pie for the combined company, and owners were assigned. Product experts from both sides offered training sessions to explain the joint product roadmap and identify innovation opportunities.

Ecolab and Nalco also focused on their top accounts and customer needs, making sure to use their sales forces to determine the long-term objectives of their top accounts and to understand how the combined company could best respond to customer needs. According to Harvard Business Review, “The company’s model was to provide on-site evaluations and training for customers and build them customized portfolios of products and services based on those visits.”3 Many of their customers had worked with both companies for years, and it was essential to maintain those strong relationships.

Cross-selling was a key opportunity for Ecolab post-close. One of the largest hotel chains in the world was a key account of Ecolab. They used Ecolab cleaning products throughout their operations from washing towels to cleaning corporate offices. Nalco, however, had not been able to penetrate that account and provide their extensive water solution services. The combined sales teams worked to articulate how the combination of Ecolab with Nalco services could enhance its existing water services and create a more complete end-to-end solution. Together the “new” Ecolab enhanced capabilities also provided specific customer-focused field services. For example, the water used for washing hotel towels could now be used to water on-site landscaping—a bundled solution as a result of the merger.

Ecolab also focused on new products and services. For instance, one of Nalco’s existing services included sensor monitoring in heating and cooling towers. These sensors collected data to help monitor operations and identify pre-emptive maintenance needs. As a long-term product development goal, Ecolab explored creating a new monitoring service that used Nalco’s sensors to track in situ product effectiveness. For example, Ecolab offered descaling chemicals used to clean and sanitize pipes that have become blocked due to buildup. Using Nalco sensor technology, Ecolab derived a method for monitoring the progression of buildup, subsequently tracking the effectiveness of their products when used by their customers to descale their pipes, allowing for predictive maintenance and reduced downtime.

Transition 5: From the Employee Experience to Change Management and Culture

In chapter 7, we wrote about how part of planning the employee experience focuses on “getting ahead of the pain”—that is, anticipating important changes for employees, function by function, across employee groups and addressing their needs so they are ready for the changes and transitions to come. Indeed, this chapter has detailed many post-Day 1 changes. They might appear straightforward to plan, but change management is hard. As Todd Jick, a Columbia Business School professor, writes in his classic piece “On the Recipients of Change”:

For most people, the negative reaction to change is related to control—over their influence, their surroundings, their source of pride, how they have grown accustomed to living and working. When these factors appear threatened, security is in jeopardy. And considerable energy is needed to understand, absorb, and process one’s reactions. Not only do I have to deal with the change per se, I have to deal with my reactions to it! Even if the change is embraced intellectually (“things were really going bad here”), or it represents advancement (“I finally got the promotion”), immediate acceptance is not usually forthcoming. Instead, most feel fatigued; we need time to adapt.4

The nature of M&A change management is even more involved because there are so many moving parts—workforce planning and transition, executing on the employee experience plan, implementing the new operating model and organization design, and managing the merger of not just two businesses but two cultures and accepted ways of working.5

Executive teams are expected to quickly create inspiring points of view about the possibilities for the future that investors and customers find believable while simultaneously needing to calm anxieties of the workforce and then inspire employees. These two goals require two carefully crafted—but different—messages, which creates a natural tension and necessitates the prioritization of parallel paths of work for executives. In the first, they manage external enterprise-level requirements. In the second, they methodically address the workforce by elevating them through their hierarchy of needs: job security, rewards, affiliation, and growth.

At the enterprise level, executives must “inspire, spark, and calm.” Inspiration and spark begin on Announcement Day and carry through to Day 1. The external market wants to know the strategy and vision: how value will be created, where the synergies lie, and the new operating model to achieve those goals. Messaging sparks their belief through sharing more detail of how the deal will improve the customer experience and create growth and value. Executives later calm the market and the board by demonstrating how the merged company is navigating the future post-Day 1, as it starts realizing the anticipated benefits.

Employees have a different set of expectations. For them, executives must “calm, spark, and inspire”—seemingly the opposite of the needs of the market. Employees care less about vision at the outset. They want to be calmed by knowing they have a job and benefits—a process that starts pre-close. Spark happens after close. Once they know they have a job, employees want to be sparked by exploring the vision for the company and the brand, building on their curiosity about the future. And then they want inspiration that will help them both affiliate with their new company and envision themselves remaining and growing at the company for the rest of their career with a sense of belonging and purpose.

Tensions can arise because the two groups—the market and employees—are looking for competing information at the same moment. A small group of executives are operating at 30,000 feet, but thousands or tens of thousands or more employees see the organization from one foot off the ground. The employee experience team often transitions to focus on change management and as the change management team they are charged with continuing to help resolve this tension. They must approach their task by refining and executing on the change management initiatives that were considered and developed pre-close.

During pre-Day 1 planning, the employee experience team worked to address employee anxieties about their future— explaining the talent selection process, communicating timelines, announcing new leaders, clarifying benefits, and preparing employees for change—the essentials of reducing uncertainty for employees as they confronted the reality of the merger so they could better focus on their role. Post-Day 1, questions like “Do I have a job?,” “To whom do I report?,” “Do I have to move?,” and “Did my benefits change?” should be answered swiftly. No one should be wondering if their ID card will work, who their insurance provider is, to whom they report, and where they sit come Day 1. This is the calm.

Once employees are assured, the issues begin to shift. It’s time to spark. The change management team will focus on creating a sense of affiliation, addressing questions like “Does this company’s values, community commitment, and brand align with my beliefs?” As employees develop a sense of connection and belonging to the organization, the moments for inspiration arrive. The change team must illuminate possibilities for employees’ future. Will they offer employees the possibility of growth, addressing questions like “What are the opportunities for advancement, mobility, and leadership?” so they will feel fulfilled for years to come.

The approach, though, requires a similar level of detail: By understanding major milestones and communicating them in a “day in the life” way, the change management team will help employees (now levels 3 or 4 and below, a much larger employee population) build a sense of affiliation and empower them to see a desired career path in the new organization.

Organizations that don’t engage in robust change management—those that rely on the mere communication of who the new leaders are or that just move employees into new roles—see attrition rates and dissatisfaction levels that are sky high. Why? Because employees simply didn’t know where they belonged—and subsequently left or became unhappy and frustrated and stayed. Other mistakes include reducing employee autonomy or making other major changes without clear explanation. If employees feel like their rights are being taken away, they’ll become unhappy and be confused about their role and their future. For example, if someone loses their direct reports, they may still opt to boss those people around if that’s what they prefer. People will selectively remember what they want and act accordingly. Remember, people don’t fail to transition because they don’t understand—so part of the change management effort is taking the time to help them feel that change makes sense and is in their best interest for the future.

The tactics of change management can include training sessions, two-way communications, and rotational opportunities. It can also include a heavier leadership engagement, with personal attention from leaders and managers to recognize and motivate employees. Each touchpoint is a chance to demonstrate core values and make them tangible. The experience must be fair for everyone but personal for each employee—including not just monetary rewards but also gestures of gratitude that show their work is valued. If you haven’t anticipated how some employee communities will experience change, then they will reject you. So post-close change management must be as carefully crafted as the pre-close employee experience: with milestones set at 30, 60, and 90 days that recognize the changes that employees are facing—especially those tied to integration milestones.

The entire process must be fair for everyone—including those who are leaving—to help those who remain work through any possible survivor guilt. As Joel Brockner, a social psychologist at Columbia University, has shown, a high-quality process (“procedural fairness”) that includes input, consistency, and accountability can help everyone feel better about the outcome.6

Culture

Any discussion of change management in M&A will converge on culture. Discussions of culture can come off as “fluffy bunnies.” But in reality, issues associated with merging cultures are complex and meaningful problems, deeply connected to integration efforts. Shared beliefs on “how work gets done around here” involve decisions rights, access to information, and rewards and incentives that can be dramatically different across companies. Those shared values and expectations didn’t happen overnight. They took years to evolve and were passed down through the generations of managers and employees.7

Company cultures are so taken for granted that someone from a different culture may view the practices and beliefs of the other as absurd—creating the seeds of a so-called culture clash. At its core, culture allows behaviors to become reasonably predictable. As a consequence, it’s imperative to pay attention to developing a shared culture early—beginning on Announcement Day. We’ve seen clients fall down when they say, “We’ll deal with culture after the work from the integration has slowed down and we have more time.” By then, it’s too late.

Organizations can differ across many dimensions that need to be assessed on what matters for the new operating model and the vision for crafting the culture of the new organization. Culture assessments will reveal differences in a sense of pride and ownership in the organization, attitudes toward inclusion, risk and governance processes, the appetite for change and innovation, a focus on customers versus products, how employees collaborate and team, the importance of informal networks, and even daily routines and rituals that impact how work gets done and what are acceptable behaviors.

Culture is also a supporting rod that can hold together the organization and drive performance. Take the extreme example of one CEO who focused relentlessly on maximizing profit. In meetings, when making decisions, it was what she and her leadership team asked about first. When they approved new products, they did so only if they met a clearly defined operating margin threshold. Employees internalized this and went to outrageous lengths to conserve costs, even foraging in dumpsters for copper wiring to use in their new product designs. Their profit-maximizing, cost-conscious culture was reinforced by a profit-sharing mechanism that paid out more than 35 percent of their base pay every year. Consider how tightly integrated that aspect of culture is: strategy to execution, supported by reinforcing incentives with a vision set by leadership.

Or consider the care that Disney took to preserve culture when it acquired Pixar in 2006 to breathe new life, technology, and innovation into its animation division. Not only was Pixar’s creative head, John Lasseter, appointed to lead Walt Disney Animation, reporting directly to Robert Iger, then CEO of the Walt Disney Company, but both parties negotiated a “social compact” of culturally significant issues. Disney promised to preserve everything such that employees felt that they were still Pixar—email addresses and signs on the building would still say Pixar and rituals like monthly beer blasts and the welcoming new employees would be retained. As Iger writes in his book, The Ride of a Lifetime, “If we don’t protect the culture you’ve created, we’ll be destroying the thing that makes you valuable.”8

Culture signals and symbols that began at Announcement Day and that were reinforced pre-close are now becoming embedded post-close, whether you want them to or not. Which leaders are chosen and their styles and values send important signals about the new culture. Employees will also observe and have feelings about the new priorities, who has influence and how will decisions be made, what gets rewarded, who has a say and gets to participate in decisions, and even what systems will be used to run the business. Each of these is a signal to employees about the shared culture that is developing through the merger. The post-close period also presents the opportunity to publicly celebrate early wins—like new accounts or successful cross-selling—to show employees what is important for future success.

And yet, each of these is under your control and should be addressed deliberately with an appreciation of the effect they will have on employees: not just on culture but on employees’ sense of affiliation and growth, keys to keeping them satisfied and productive and seeing themselves as part of the company for a long time to come. If culture is the shared norms around how work gets done, and how work gets done is going to change, then the opportunity is to take an active role in shaping new shared norms, rather than coming to them too late when employees have already decided and their new behaviors have calcified.9

Culture at Ecolab

In the April 2016 issue of Harvard Business Review, Jay Lorsch, of Harvard Business School, and his associate, Emily McTague, interviewed Ecolab CEO Doug Baker on how he shaped the company’s culture. Baker had taken over at Ecolab in 2004 when revenue was $4B and grew it to $14B in 2014 by completing more than 50 acquisitions, including Nalco as the largest. The workforce had more than doubled during his tenure.10

As Ecolab absorbed new acquisitions, complexity and organizational layers grew and divisions and managers became siloed. As Lorsch and McTague write, “The expanding bureaucracy was eating into Ecolab’s customer-centric culture, and that was hurting the business.”

Baker aimed to restore customer focus and customized offerings as a core strength—and that meant a major change effort. He focused on pushing decision-making to the front lines, to the employees who were closest to customers. Ecolab also engaged with those frontline employees by training them on all Ecolab’s products and services so they would be better equipped to figure out on their own which solutions best fit customers’ needs.

Although it seemed risky to push decisions down, Baker “found that the bad calls were caught and fixed faster that way. Eventually, managers began to let go and trust their employees—which was a huge cultural shift.” Ultimately, that fostered frontline responsibility and allowed Ecolab to stay connected with its customers as their needs evolved.

Baker championed an important tool in change management and culture shaping: public acknowledgment through promotions and recognition. Lorsch and McTague write:

Baker also emphasized the importance of meritocracy in motivating employees to carry out business goals. ‘People watch who gets promoted,’ he says. Advancement and other rewards were used to signal the kind of behavior that was valued at the company. Baker found that public acknowledgment mattered even more than financial incentives over time. ‘What do you call people out for, what do you celebrate, how do people get recognized by their peers? The bonus check is not unimportant, but it is silent and it’s not public,” he points out. Kudos went to managers who delegated decisions to customer-facing employees and encouraged them to take the lead when they showed initiative.

This collaborative approach across divisions had long-lasting positive effects on the new Ecolab:

As frontline employees were rewarded for owning customer relationships and coordinating with one another, a culture of autonomy emerged. (This also freed up senior management time, allowing executives to focus on broader issues.) Once people throughout the ranks felt trusted, they in turn trusted the company more and began to view their work and their mission—to make the world cleaner, safer, and healthier—as real contributions to society. And in their enhanced roles, they could see firsthand how they were making customers’ lives better. This shift took time, though, because the process had to happen again and again with each acquisition.

“When we buy businesses, they’re not going to love the new company right away,” Baker says. “Love takes a while.”

Conclusion

Leading up to Day 1 is a sprint. Post-close is marathon. While Day 1 is an exciting—and important—milestone and should rightly be celebrated, there is still much work to do after Day 1—but it’s finite. The goal, remember, is to create a fully integrated and aligned organization—strategically and operationally—that can achieve the promise of the deal thesis. With thorough planning and disciplined execution, that goal is attainable—helping the organization to achieve greater returns and create even greater value than employees, investors, customers, and the board expect.