CHAPTER THREE

ALIGNING FINANCIAL AND CUSTOMER STRATEGIES

ENTERPRISES CAN CREATE organizational synergies in many ways. Some enterprises leverage financial synergies through effective merger and acquisition policies and skilled management of internal capital markets. Others leverage a common brand or customer relationship across multiple business units and retail outlets. Still others gain scale economies by having multiple business units share common processes and shared services, or they generate economies of scope through effective integration of units across an industry value chain. And finally, enterprises create synergies when they develop and share human, information, and organization capital across multiple units. Corporate headquarters must be explicit about the synergies it expects to create and then must implement a management system to communicate and capture them.

In this chapter, we describe examples of corporations that create value by leveraging financial and customer synergies. In Chapter 4, we continue the analysis by presenting opportunities for leveraging critical internal processes and for integrating learning and growth capabilities across the enterprise. In both chapters, we show how private-sector companies, public-sector agencies, and nonprofit organizations have created enterprise-derived value through specific attention to sources of synergy.

FINANCIAL SYNERGIES: THE HOLDING COMPANY MODEL

All enterprises have the opportunity to generate synergies by using centralized resource allocation and financial management, but we get the purest example by focusing on holding companies, which consist of business units or companies that operate largely as independent entities. These companies create synergies only through their financial competencies and practices. Typically, a holding company’s operating units are located in different regions, operate in different industries, sell to different customers, use different technologies, and craft their own strategies.

Such a situation also occurs in the public sector, where governmental departments often consist of a collection of independent agencies whose operations overlap little and do not have to be tightly coordinated. Consider the U.S. Department of Transportation, which consists of thirteen mostly autonomous agencies, including the Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Association, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, Federal Railway Administration, Federal Maritime Administration, and the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration. Each of these agencies has its own constituency (e.g., airlines, railroads, public transit, trucking, ships, and automobiles), mission, and strategy.

Chapter 2 describes how 1960s-era corporations—such as Litton Industries, ITT, Textron, and Gulf + Western—followed a strategy of aggressive acquisitions, putting together under one organizational structure a collection of companies that had few shared capabilities, technologies, or customers. The espoused rationale for this conglomerate movement was twofold: first, the corporation gained access to new industries that promised more growth and less competition than its existing businesses, and second, the acquisition strategy reduced the corporation’s risk by holding a portfolio of companies whose business cycles were not correlated.

Neither rationale eventually stood up to economic scrutiny and practical experience. Although some businesses do have higher growth opportunities than others, the current stockholders of those higher-growth companies normally understand these opportunities reasonably well, and the growth is already reflected in the current share price. Therefore, the acquiring company pays a considerable premium to purchase the growth company. Many studies have shown that in a merger or acquisition, sellers generally capture all the gains, and purchasers suffer a winners’ curse, overpaying for growth and subsequently earning below-market returns from their acquisitions.

On the alleged risk-reduction benefits, most investors already own a sufficient number of companies to achieve their own diversification from firm-specific risk. They don’t need to have company managers pay a premium price to perform this diversification for them. And, in any case, most conglomerates failed even in their home-grown risk-reduction strategy. During the economic slowdown of the 1970s, virtually all the companies they owned suffered together, leading to major difficulties in servicing the debt taken on during the aggressive acquisition phase of the 1960s.

The conglomerates realized disappointing earnings growth and risk reduction during the 1970s, and this disappointment was followed, in the late 1970s and through the 1980s, by a wave of takeovers, divestitures, and management replacement. Nevertheless, the lure of growth and the reduced risk to executives of diversified companies continue (to say nothing of the high fees earned by the investment banks that organize companies’ merger and acquisition activities), and many such corporations still exist. The huge challenge faced by the executive teams in their corporate headquarters is how to overcome historical experience. They must demonstrate that they can select and manage a collection of unrelated businesses to create value superior to what the businesses could earn separately.

The leading examples of companies in this category, such as Berkshire Hathaway and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), are pure investment or private equity corporations. Each company in an investment or holding company portfolio is managed and financed independently. Each has its own board of directors, which usually includes representatives of the parent corporation. There are no cross holdings, and cash flow from one company cannot be used in another company.

The gains from this type of corporation arise from two sources of financial synergy. First is the investment acuity of the principal owners, such as Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway and the KKR senior partners. These owners create corporate value by their ability to identify undervalued or turnaround company situations. They also follow an excellent due diligence process to support their initial opportunity identification. In effect, this capability requires having superior information or performing superior analysis so that the corporation can “buy low and sell high” consistently.

The second source of financial value creation comes from operating an effective governance system that monitors and guides the long-term performance of the portfolio companies and their senior executives. Holding companies frequently assist in the acquisition and assignments of key personnel as well as introduce professional management approaches.

For example, FMC Corporation, one of the earliest adopters of the Balanced Scorecard, operated more than two dozen companies in the machinery, chemicals, minerals, and defense industries. Senior corporate executives had extensive experience within the operating companies. They also had private information about the opportunities, threats, capabilities, and weaknesses of their operating companies and their markets. The headquarters executives used their extensive experience and private information to make better decisions about resource allocation than the public capital markets would have made. For example, one of FMC’s companies produced airport equipment for baggage handling, passenger transportation to and from aircraft, and jetways and loading ramps. During one of the typical down cycles of the airline industry, investment was depressed throughout the industry. FMC’s company made a strategic investment to acquire its largest competitor at a price highly discounted from what FMC executives perceived was its long-term value. This decision was more than validated during the next upswing in airport expansion and investment.

So the enterprise value proposition for a highly diversified corporation includes a superior ability to allocate capital and manage risks in its diverse businesses. The financial objectives on its corporate scorecard should include common high-level metrics such as economic value added and return on net capital employed. The financial metrics provide a common benchmark for measuring the financial contribution of each company in the corporate portfolio. Of course, even in a highly diversified corporation, the headquarters executives are active portfolio managers and can highlight different financial metrics among the varied portfolio to facilitate resource allocation. They may choose to emphasize sales and market share growth for a company early in its product life cycle, while emphasizing the generation of free cash flow for a company in its more mature phase.

The case studies here of Aktiva and New Profit Inc. show how enterprises seeking such financial synergies can deploy the Balanced Scorecard to play a central role in their governance system for a portfolio of unrelated business units.

CASE STUDY: AKTIVA

Aktiva, a private investment holding company, was founded in Slovenia in 1989 and currently is headquartered in Amsterdam, with offices in Geneva, Ljubljana, London, Milan, and Tel Aviv. Company assets in first quarter 2004 were €600 million, and the assets in the thirty companies in fourteen countries that Aktiva controls directly or with strategic partners exceed ∈12 billion.

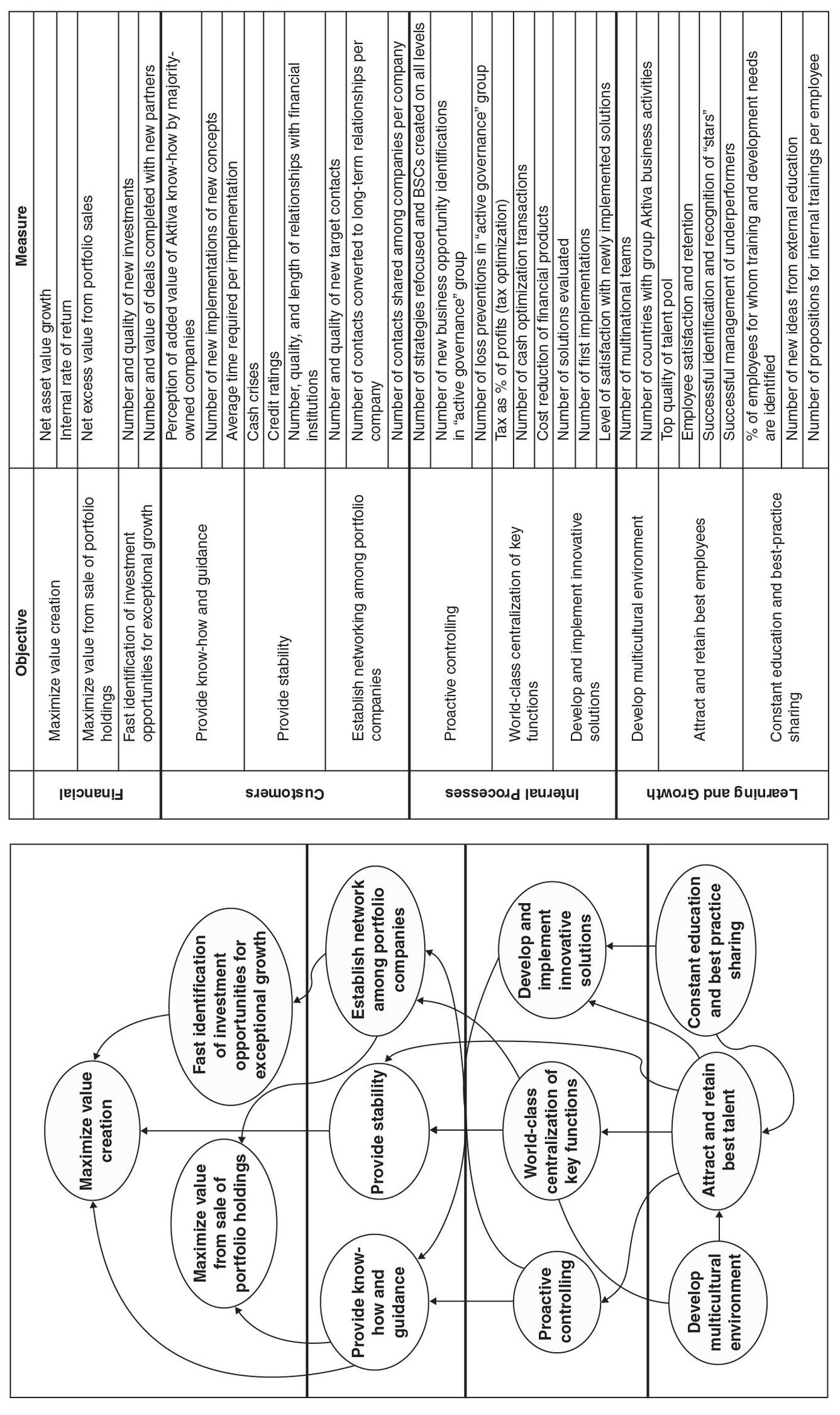

Aktiva uses an active governance approach that transfers leading-edge management theory, practice, and discipline to its portfolio companies. Aktiva’s initial strategy used value-based management and measures of economic value added to provide financial discipline and focus for its operating companies. By 2000, it saw the opportunity to more actively assist its portfolio companies by requiring each company to develop a Balanced Scorecard to describe and implement its strategy. Aktiva started by developing a Balanced Scorecard for itself that described how it would maximize its value through active management and governance of its portfolio companies (see Figure 3-1). It then assisted each of its portfolio companies to develop and implement its own Balanced Scorecard.

Aktiva established what it called an “active governance group” in its corporate structure. The managers in this group move to the geographic locations of member companies. There, they provide day-to-day help, coaching the company’s executive teams in their development of the Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards that describe and help the company managers implement their strategies. Each assigned member of the active governance group participates in the incentive scheme of the portfolio company, gaining a strong incentive to help the company succeed. Incentive schemes for upper and middle managers in each portfolio company are linked to personal scorecards and to the company scorecard.

Aktiva executives meet quarterly (and often monthly) with the executive team of each portfolio company to review its performance on its Balanced Scorecard and to suggest ways to solve problems and improve performance. These meetings, attended by corporate active governance group members, also provide an opportunity for knowledge and experience generated in one portfolio company to be rapidly transferred to all the others.

Aktiva’s active governance process, using value-based management and the Balanced Scorecard, has been highly successful. The return on net assets of Aktiva’s largest investments rose from a negative 2 percent in 1998 to positive 12 percent in 2003. Pinus TKI, a Slovenian-based agricultural chemicals company in its portfolio, doubled its sales from 1996 to 2003 and transformed a negative ∈1.5 million economic value added in 1996 to a positive €1.5 million in 2003.

Aktiva, as an investment company and not as an operating company, periodically sells a company when it can get a price that fully reflects the company’s underlying value that Aktiva has helped to generate. Interestingly, companies that Aktiva has sold, even when no longer under Aktiva’s active governance mandate, continue to use their Balanced Scorecards—a tribute to the belief, within each portfolio company, of the value of this management and governance tool. Aktiva CEO Darko Horvat testified to the value of the Balanced Scorecard for his private investment company:

Figure 3-1 Aktiva Corporate Active Governance Strategy Map

Before we implemented the BSC, Aktiva was growing exceptionally fast, but there was always a danger of focusing too much on only financial KPIs (key performance indicators). We were aware that such financial results are not sustainable for several years. By implementing the BSC, our focus moved from EVA to the other three perspectives, which, in the end, are those that contribute most to the future as well as to the financial success of the company. For us, the BSC is irreplaceable and is the backbone of how we conduct our business in a strategy-focused way. We look on it as an essential part, deeply integrated into the way of our success.1

CASE STUDY: NEW PROFIT INC.

A nonprofit version of the investment company model has also enjoyed great benefits from use of the Balanced Scorecard. New Profit Inc. (NPI), a venture philanthropy organization, attracts large donations from individuals, foundations, and corporations interested in contributing to entrepreneurial nonprofit organizations that can demonstrate proven track records and have the potential to go to scale.2 NPI provides multiyear funding to its portfolio organizations that enables them to build capacity for growth. Much like private-sector venture capital firms, NPI holds its portfolio organizations accountable to achieve mutually agreed-upon targets on measurable performance criteria. NPI sustains its funding to these organizations as long as they continue to reach their goals.

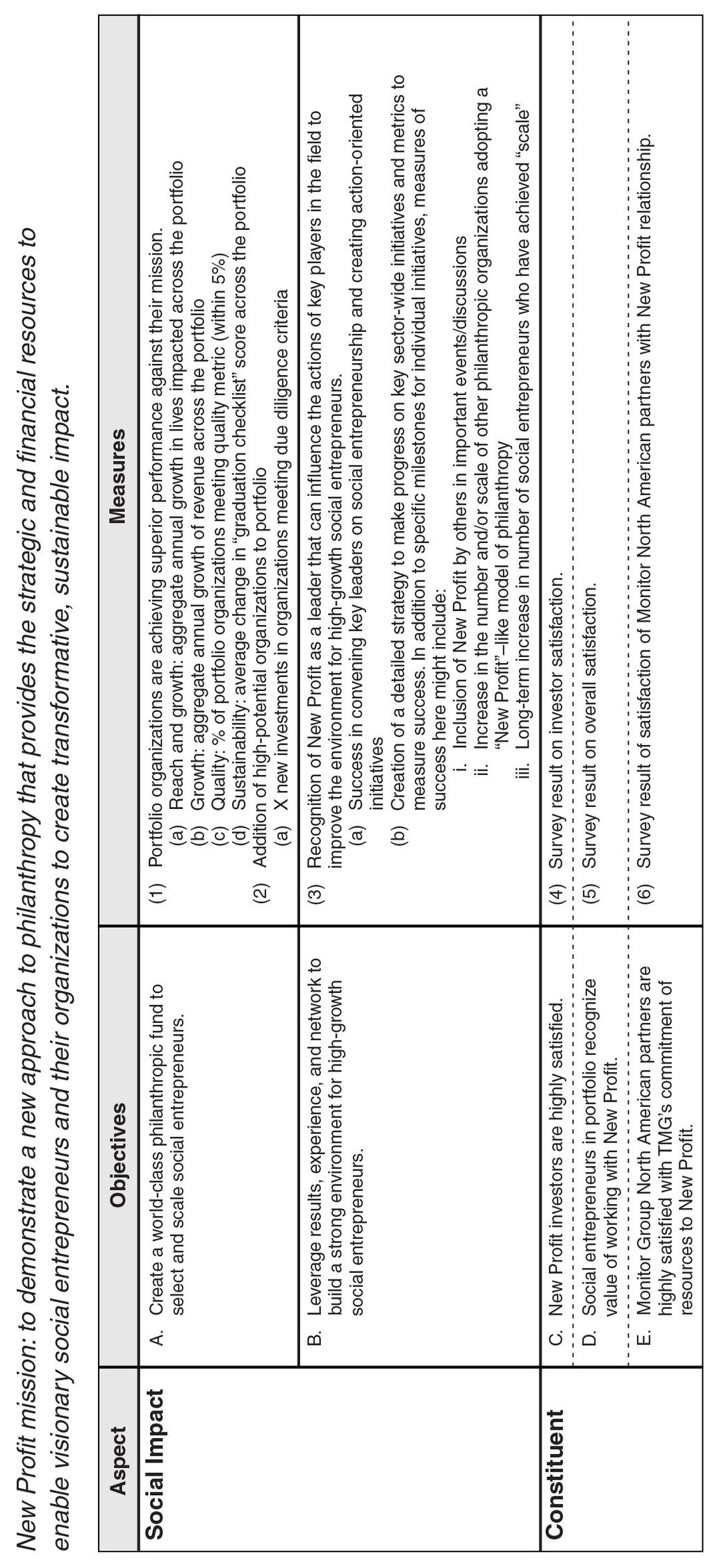

Unlike private-sector investment, private equity, or venture capital firms, NPI cannot use financial measures to assess the performance of its investments in nonprofit organizations. The success of its portfolio organizations is measured by their social impact, not their ability to raise funds or balance their budgets. NPI’s founding partners turned to the Balanced Scorecard as the best tool for establishing a performance contract with, and subsequently evaluating the performance of, each of its portfolio organizations.

NPI started by developing a corporate-level Balanced Scorecard for itself (see Figure 3-2). NPI developed its scorecard with its own board and with potential and existing investors so that it could be held accountable for its own performance, much as it would demand that portfolio organizations be accountable for theirs. The NPI corporate-level scorecard served as a template for the scorecards subsequently developed in the portfolio organizations. This allowed all portfolio organization scorecards to have a similar structure, facilitating communication with NPI board members and investors while still allowing the portfolio organizations to customize the objectives in the various scorecard perspectives to fit their individual missions and constituents.

Figure 3-2 New Profit 2005 Balanced Scorecard

Once NPI built its corporate scorecard, its personnel worked with the portfolio organizations, helping them design and implement Balanced Scorecards tailored to their specific goals. NPI now monitors the performance of its portfolio organizations by how well they deliver on their individual Balanced Scorecard measures and targets. In semiannual reporting, NPI partners share with “investors” (i.e., contributors) a summary of each organization’s Balanced Scorecard so that the investors see the social impact and performance of each portfolio organization.

NPI’s enterprise value proposition includes an excellent due diligence process that identifies promising investing opportunities for social impact and growth. NPI also maintains an active monitoring and governance process that holds the social entrepreneurs accountable for delivering measurable results, and it provides management consulting to coach and advise the entrepreneurs on how to build more effective and efficient organizations. Because there is no capital market for funding the growth of nonprofit organizations, NPI creates substantial social value by enabling high-performing social enterprises to access long-term financing for growth and capacity building.

Each portfolio organization, in thought partnership with New Profit, creates its own scorecard, based on its mission, constituents, and value proposition. NPI provides only the broad template—showing perspectives for social impact, clients, financial, people, and resources—and each portfolio organization fills in its own scorecard.

FINANCIAL SYNERGIES: CORPORATE BRANDS AND THEMES

Corporate headquarters can also create value by proactively leveraging resources, capabilities, or information throughout the individual entities. For example, highly diversified corporations, such as General Electric, Emerson, and the FMC Corporation, consist of a group of mostly autonomous sectors or companies in different industries. The enterprise value proposition for such highly diversified corporations comes primarily from headquarters executives’ ability to operate internal capital markets better than external market mechanisms do (as with holding companies), and, in addition, the sharing of common themes or information across the units in a way that would not occur were each operating company to be an independent, market-facing entity.

Such diversified corporations follow a bottom-up approach, with the corporate parent approving the company-level scorecards as each is created and then monitoring each operating company according to its specified strategy for value creation. The corporate parent may impose a structure—such as which financial metrics must appear in each scorecard—and general themes for the various perspectives: “become our customers’ most valued supplier,” “achieve six sigma levels of quality in all operations,” “be the industry leader in environmental and safety performance,” “recruit the best talent,” and “leverage technology for process improvement.” The operating companies interpret these general guidelines in their own contexts and build their individual scorecards to capture their local strategies in a way that is consistent with corporate guidelines.

Many other corporations, although not exactly conglomerates, also fall into this category. All the operating units may be in the same broad industry category, such as financial services or discrete part manufacturing, but they still operate with different strategies and in different industry segments. For example, suppose a corporation consists of life sciences companies; some companies are innovative product leaders, others produce commodity products and compete on low cost and excellent quality and delivery, and still others offer an integrated set of products and services to their targeted customers. These corporations too must identify their enterprise value proposition: how their loosely connected set of companies can produce additional value by operating within the same corporate structure.

Most successful diversified corporations have distinct competencies that they leverage throughout their operating companies. For example, Emerson’s companies operate in mature industries, involving engineered products, where success involves highly efficient manufacturing processes using electrical and mechanical technologies. FMC’s companies operate in mature, capital-intensive industries, with slowly evolving technological processes. Many of General Electric’s eclectic collection of businesses—including locomotives, aircraft engines, financial services, health care, energy, water treatment, and broadcasting—have long development and contracting cycles. Such homogeneity provides the opportunity for the corporate parent to add value throughout the operating units.

Some highly diversified corporations find it beneficial to develop a branding strategy to promote cohesion in the eyes of investors and customers. The values represented by the brand transcend the strategies of operating companies. General Electric has, over its history, branded its corporate businesses with a series of overarching themes: “We Bring Good Things to Life,” “Progress Is Our Most Important Product,” and “Live Better Electrically.” Today, to signify a renewed emphasis on innovation, GE has introduced a new theme, “Imagination at Work.” Each GE operating company now communicates how imagination brings new products, services, and solutions to customers.

For more than a century, Emerson Electric was known as an organization of companies that offered low-cost engineered products to customers. With its new (shortened) name, Emerson has repositioned its brand, as did GE, to stress innovation and technology. It communicates that each of its operating companies, all of whose names now begin with the company name, Emerson, will deliver on the corporate brand promise:

At Emerson, we bring together technology and engineering to create solutions for the benefit of our customers. We deliver the forward-thinking answers our customers require to succeed in a world in action. We are driven without compromise to bring our customers quality solutions deserving of the Emerson name.

For businesses around the world, the Emerson brand represents global technology, industry leadership and customer focus. For the investor, the Emerson name symbolizes our proven management model, successful growth strategy, and strong financial performance. For employees, the Emerson experience means opportunities to grow, prosper, and make a difference.3

The Balanced Scorecards of highly diversified corporations may also have customer and internal process objectives. The customer perspective in the corporate Balanced Scorecard can include desired customer outcomes, such as brand image and customer acquisition, satisfaction, retention, market share, and profitability. The objectives typically do not include objectives or measures describing a customer value proposition because each operating company will have its own customized value proposition for its targeted customers.

For the internal perspective, diversified companies often articulate corporate-level themes for critical processes such as six sigma quality, e-business capability, and excellent environmental, safety, and employment practices. For example, many corporations have embraced quality, such as six sigma programs, as a corporate theme. Headquarters encourages its operating companies to compete for national and international quality awards to demonstrate leadership in quality processes. Companies operate internal quality award programs to foster competition among their operating companies.

To avoid the consequences to the entire corporation from a local failure or incident, the corporate parent may also want each operating company to excel at regulatory and social processes. A product liability problem, a company bribery incident, a dismal environmental reputation, or frequent employee safety and health concerns in any single operating company can produce highly unfavorable publicity that affects the financial resources and viability of the entire corporation. On a more positive note, exceptional performance on employment, environmental, health, safety, and community objectives may attract customers, investors, and employees for all the corporation’s companies.

Excellence in regulatory and social processes can help the corporate brand to the benefit of all its operating companies. For example, business groups such as Tata and Siam Cement require that their operating companies live up to contracts in order to earn a reputation as a good company to do business with, even though strict contract enforcement may not be required given the lower incidence of independent and bribery-free judiciaries in the developing nations in which these business groups operate.4 Amanco, based in Central and South America, has developed a Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard based on three bottom line performance measures—economic, environmental, and social—to position itself as a leading progressive corporation in all regions in which it operates.5 Diversified corporations that expect to leverage gains from excellent performance in operating, regulatory, and social processes can reflect objectives on these corporate-level themes in the internal perspective of their corporate Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecards.

We illustrate the development of a diversified company Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard with Ingersoll-Rand, a corporation that generated increased shareholder value by clarifying its corporate brand and focusing its line businesses on common themes.

CASE STUDY: INGERSOLL-RAND

Founded more than 130 years ago as a specialist in construction and mining equipment, Ingersoll-Rand (IR) is now a diversified manufacturing corporation with annual sales of more than $10 billion. Its corporate portfolio consists of numerous successful brands, such as Thermo King (refrigeration), Bobcat (construction), Club Car (golf carts and utility vehicles), and Schlage (security and safety).

IR historically was a product-centered business, with each brand having its own customers and sales channels. IR’s operating companies delivered strong results, and growth in corporate earnings per share exceeded 20 percent for six consecutive years, from 1995 to 2001.

Herb Henkel became president and CEO of IR in 1999. He wanted to continue the IR businesses’ product-driven excellence that had delivered past success, but he now wanted to unleash cross-business integration that would provide a new source of revenue and growth. Cross-business integration would let IR better leverage its sales channels, products, and customer base as well as the knowledge and experience of its people. Henkel recognized, however, that such cross-business integration was counter cultural at IR. A major transformation of IR, from top to bottom, would be required.

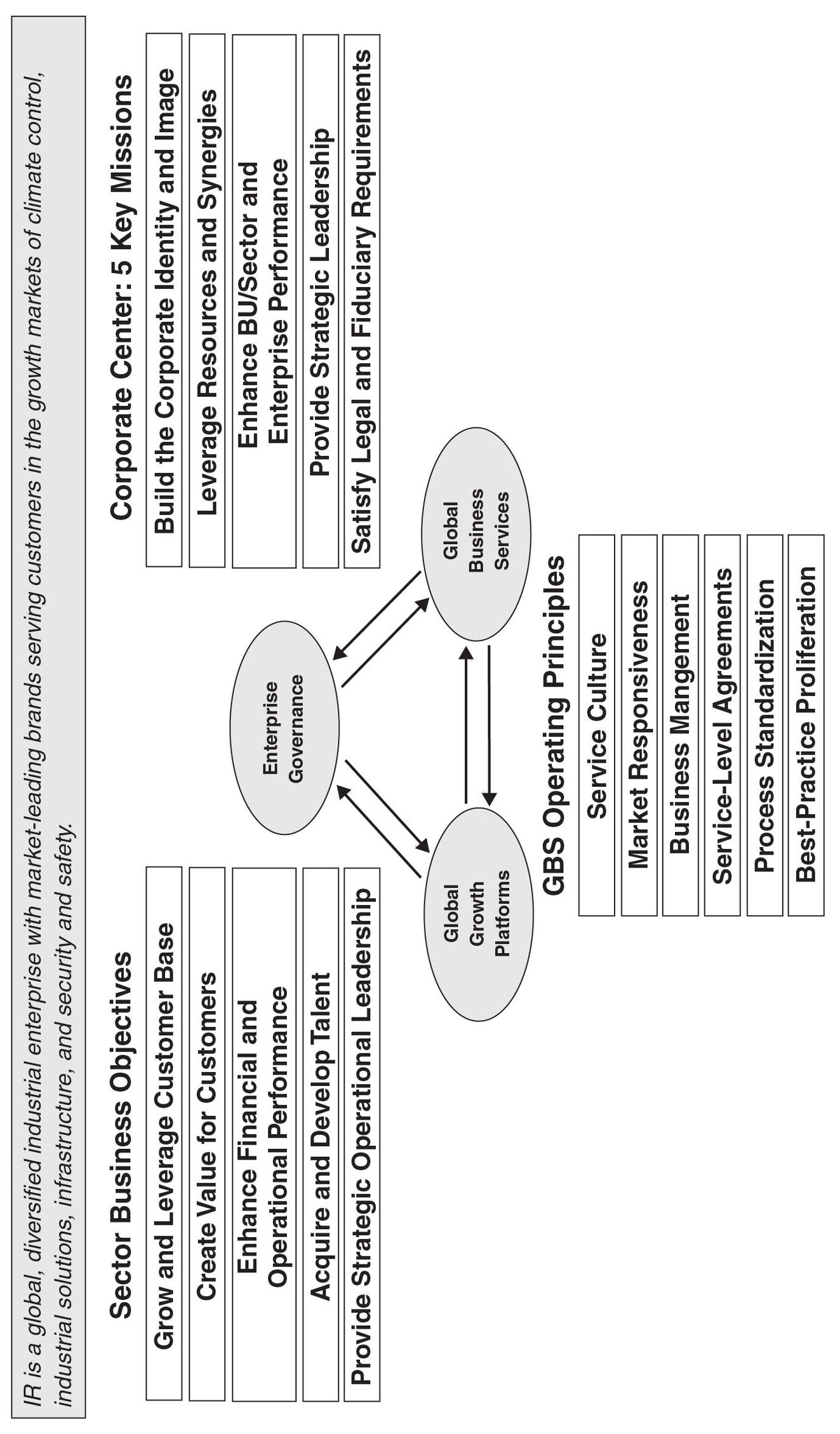

The change started with the creation of a new corporate architecture based on the corporate strategy (see Figure 3-3). Henkel organized all the previously independent product businesses into four global growth sectors: Climate Control, Industrial Solutions, Infrastructure, and Security and Safety. The sectors would create more market focus, share sales channels, and provide opportunities to cross-sell products. Companies within the sectors would strive to create new customer value by providing solutions to customer problems instead of simply selling products. Teamwork within these sectors would be the primary source of synergy.

The corporate center would create enterprise-derived value by implementing cross-business integration and by increasing the value of IR’s brand with investors. The corporate center now had five key missions:

- Build the new corporate identity for the benefit of customers, employees, and investors.

- Create leverage and synergy with IR’s resources.

- Enhance the performance of the sectors.

- Provide strategic leadership.

- Satisfy legal requirements.

Henkel collected IR’s shared-service organizations into a new unit, Global Business Services (GBS), which represented the third element of the new architecture. In the past, shared services had often micromanaged business issues. GBS was now responsible for creating standard processes and for proliferating best practices to facilitate and enhance cross-business synergies. Service-level agreements between GBS and the sectors provided the mechanism for achieving such synergies.

Figure 3-3 Ingersoll-Rand Corporate Architecture

The creation of the corporate architecture was an important and essential first step in the IR strategy execution. It unfroze the IR executives, showing the need for change in spite of six consecutive years of exceptional performance. It created a new way of managing and established clear accountability; both objectives were designed to move executives outside the comfort zone of their past. Having created the management infrastructure, IR then developed its enterprise Strategy Map to translate the high-level corporate strategy into operational terms. The enterprise Strategy Map used corporate themes as guidelines for sector planning.

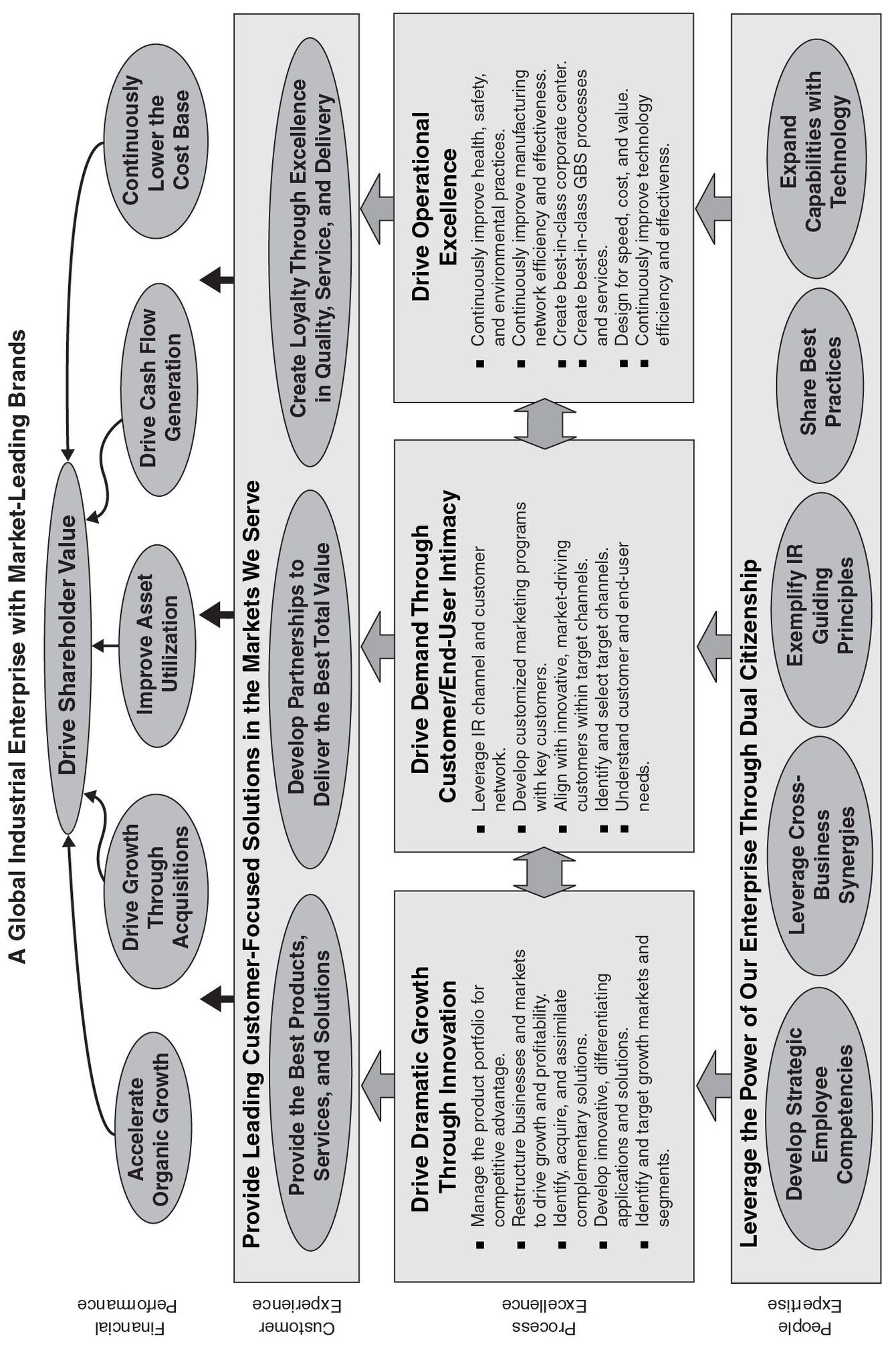

The Strategy Map template described a common philosophy—the philosophy of the new Ingersoll-Rand—that would provide the foundation for the strategy of each business unit. As shown in Figure 3-4, the financial objectives were straightforward: increase revenue, reduce costs, and use assets efficiently. The customer perspective captured the essence of the new strategy from the perspective of customers and markets. Providing solutions would shift the business focus from a narrow product strategy to one based on personal relationships that exploited the knowledge of IR personnel.

The process dimension of the scorecard was organized around the three fundamental process themes—operational excellence, customer intimacy, and product innovation—that each sector would subsequently adopt and adapt to its situation. For example, “drive operational excellence” required each sector to develop strategies that would continuously improve health, safety and environment, manufacturing, and technology. “Drive demand through customer intimacy” required each sector to develop customized marketing programs with key customers. “Drive dramatic growth through innovation” required each sector to develop innovative, differentiating applications and solutions. The specifics of the approaches developed by sectors and business lines would differ dramatically, based on the unique features of their situation. Yet all sectors and businesses would now use a common framework to view the marketplace.

The people perspective of the strategy identified the most important dimension of the corporate change agenda: dual citizenship. Historically, all personnel worked for a single line of business. Although this strategy provided clear benefits, it meant that tangible and intangible assets were locked up, incapable of being used elsewhere in the corporation where additional payoffs could be realized. Dual citizenship sent a message to all employees in the organization to think beyond the limits of their individual business units and find ways to create cross-business value for other IR businesses. Ultimately, this theme would result in divisions sharing factories, and employees selling the products of other divisions to their customers. IR set a target to create several hundred million dollars’ worth of such cross-business value, all of which would be new, an increment to business as usual.

Figure 3-4 Ingersoll-Rand Enterprise Strategy Map

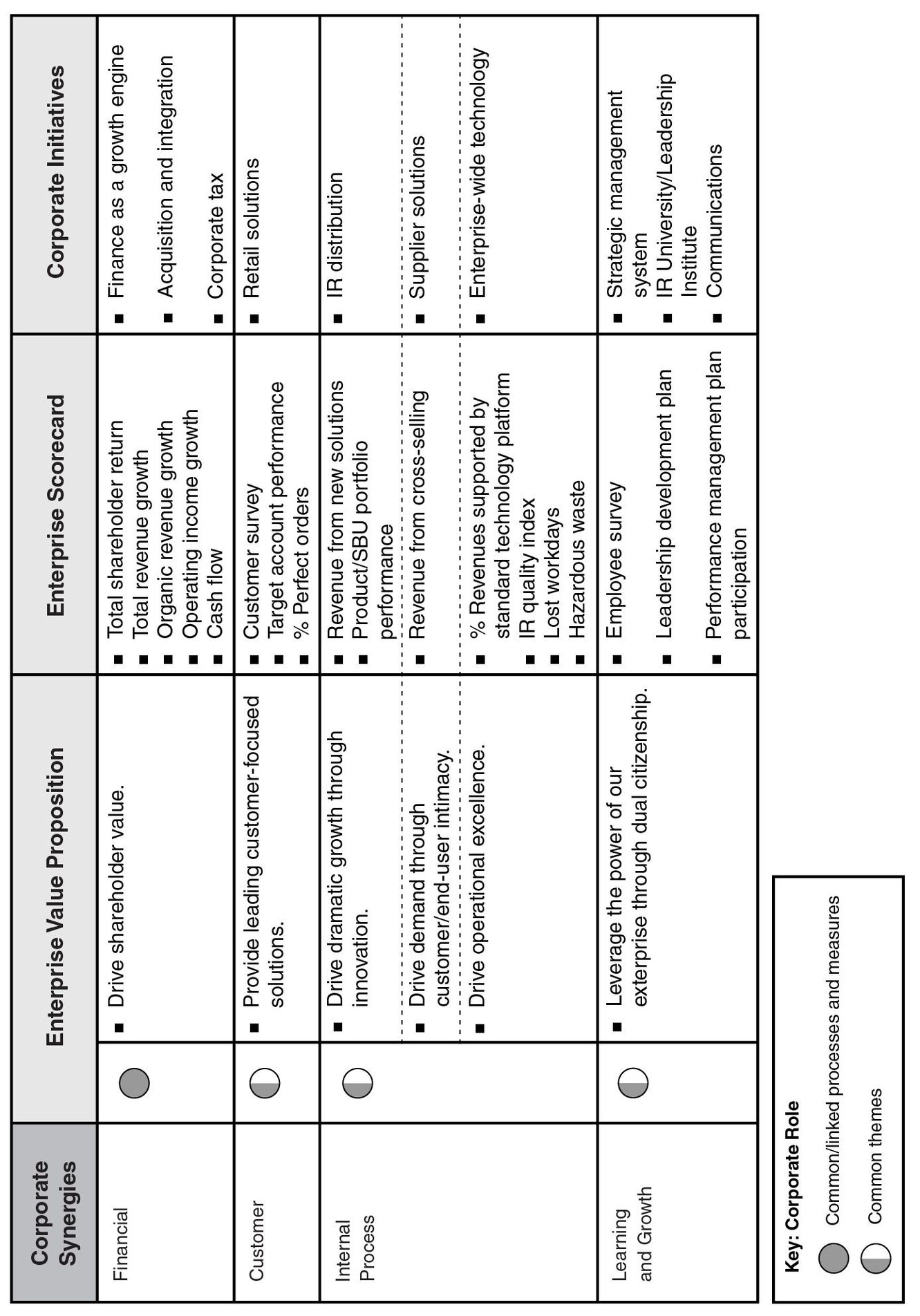

The corporate scorecard was cascaded to each of the sectors and business units, which, in turn, developed their own Strategy Maps consistent with the corporate template. The corporate strategy was supported by a set of “One Company” initiatives, shown in the rightmost column of Figure 3-5. These initiatives provided the actions necessary to execute the corporate dimensions of the new strategy.

As the final dimension of IR’s transformation and alignment strategy, Henkel created a new Enterprise Leadership Team (ELT) consisting of key executives from the sectors, from Global Business Services, and from the corporate center. Each executive was responsible for the operation of his own business or support unit, but collectively they accepted the mission to be stewards of the performance of Ingersoll-Rand, the corporation.

ELT responsibilities included the following:

- We are leading (corporate financial success) together.

- We help define dual citizenship and remove barriers to its success.

- We lead the strategic initiatives together.

- We lead IR’s communication team.

- We own talent and diversity.

- We are mentors creating mentors.

The creation of the Executive Leadership Team, the new corporate architecture, the corporate Strategy Map, the corporate Balanced Scorecard, and One Company initiatives provided an operational framework to make Ingersoll-Rand more valuable than the sum of its parts.

Since 2001, the company’s reported diluted earnings per share have tripled; its cash flow generation has greatly expanded, with virtually a tenfold increase in cumulative cash generated compared with the decade earlier period between 1991 to 1994; and its operating margins have improved from 6.3 percent in 2001 (excluding restructuring charges) to 11.9 percent in 2004.

At the same time, the company has doubled its base of recurring revenues through a focus on services and aftermarket business (which is a critical piece of the company’s growth strategy) and has dramatically improved its balance sheet, reflected by a debt-to-capital of 24.2 percent at the end of 2004 compared with 46.3 percent at the end of 2001.

Figure 3-5 Ingersoll-Rand Enterprise Balanced Scorecard (Partial)

SYNERGIES FROM SHARED CUSTOMERS

Many decentralized corporations have business units that sell to the same customers. For example, Datex Ohmeda (DO), a subsidiary of Instrumentarium Corporation (now part of GE Healthcare), was historically organized by product units. These units developed innovative products for acute-care health systems, including anesthesia machines, ventilators, and drug-delivery systems. The different product lines, many added through acquisition, were sold by different sales forces, each focusing on the technical merits of its individual hardware system.

DO executives saw an opportunity to leverage its multiple business units by shifting from a product-driven strategy to a customer relationship approach that emphasized total solutions for its health-care delivery customers. By integrating the sales force to create customer account teams, DO increased the scope of its products and services to customers, leading to greatly increased revenue per account.

In general, corporations whose operating companies sell to common customers have the opportunity to leverage their multiple products and services to create unique customer solutions, resulting in customer satisfaction and loyalty that less diversified and more focused corporations cannot match.

The BSC customer perspective of such corporations features the outcomes and value proposition related to providing customers with more complete solutions. For example, a customer outcome objective might be to increase the share of the customer’s wallet, measured by the percentage of the customer’s spending in its category that is being captured by the corporation as a whole. Other objectives are to increase the number of different products and services used by targeted customers, the lifetime profitability of acquired customers, and the quality of complete solutions offered to customers. Objectives for internal customer management processes include acquiring high-potential-value customers that could benefit from receiving integrated solutions, cross-selling existing customers to acquire additional products and services, and retaining and growing the business of these targeted customers.

Some public-sector organizations have also adopted a corporate strategy to share customers across business units. The municipalities of Charlotte, North Carolina, and Brisbane, Australia, recognized that their operating departments had common customers, in their cases, the citizens and businesses in the city. Charlotte and Brisbane each developed a city level Balanced Scorecard to articulate a strategy to make it the number one city in the region in which to live, work, and recreate. The operating units in the city—such as police, fire, sanitation, utility, planning, housing, parks, and recreation—then built their scorecards to deliver the citywide value proposition that would differentiate Charlotte and Brisbane and make them better than communities that operated with less focus and attention to their common customer, the citizen. Each department had to integrate its offerings with those of other city departments to provide a uniquely great experience for local residents and businesses.

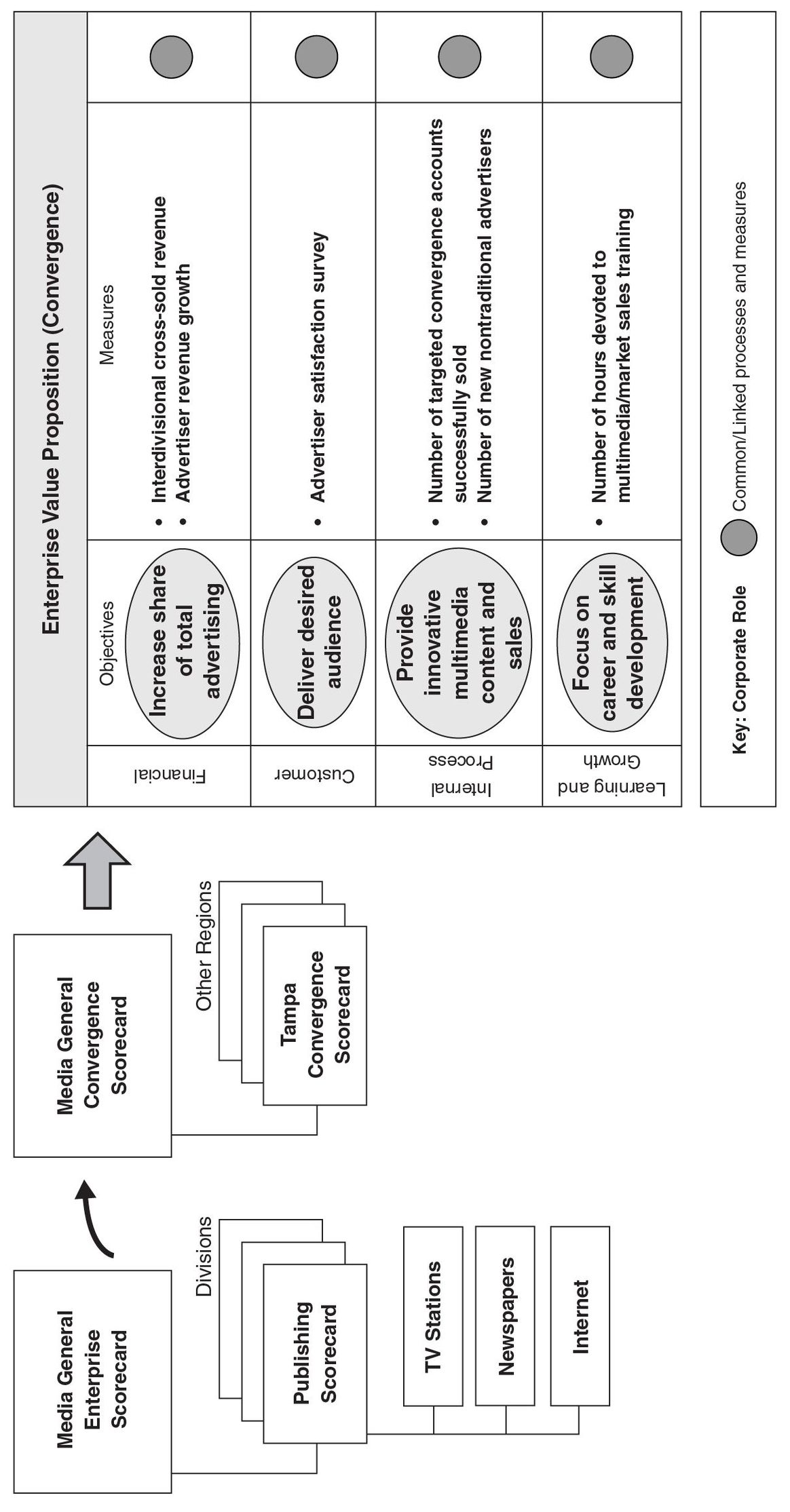

The following case study of Media General describes a corporate Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard designed to realize the benefits of sharing customers across multiple business units.

CASE STUDY: MEDIA GENERAL

Media General is a southeastern U.S. media company with revenues in 2003 of $837 million and nearly eight thousand employees. As of 2003, it owned twenty-five daily newspapers with a combined circulation of more than one million; more than one hundred weekly newspapers; twenty-six network-affiliated television stations reaching more than 30 percent of TV households in the Southeast (8 percent in the United States); and more than fifty Web sites related to its newspapers and TV stations.

Media General was founded more than 150 years ago and until the 1990s had a history of somewhat unsystematic growth, purchasing diverse publishing and media properties around the United States. Competitive pressures and the explosive growth of cable TV and the Internet, however, had depressed the value of Media General’s stock. When J. Stewart Bryan III became chairman and CEO in 1990, the company embarked on a massive transformation, shedding old businesses and acquiring others to refocus on its historic roots in the Southeast. It divested all properties outside the region and, in 1995, owned only three newspapers, three television stations, and interest in a cable company and a newsprint company. During the next five years Media General purchased twenty-two newspapers and twenty-three TV stations, all in the Southeast, and sold its cable and newsprint interests.

The company could now exploit its regional concentration to embark on a new strategy based on convergence. Bryan wanted to create synergy by exploiting the individual and collective strengths of Media General’s three divisions: newspapers, TV, and interactive media. His goal was to coordinate different media in a given market to provide quality information in the way that each does best—but delivered from a comprehensive and unified perspective.

Media General would bring together the unique strengths of print, broadcast, and interactive media to give customers in its core regional markets continual access to a seamless set of content platforms. It would leverage its three properties in each region to make them the preferred local sources of news and content for local residents. The concentration of the three related properties would also enable Media General to offer advertisers a high-quality audience to which they could direct integrated multimedia advertising packages.

The new convergence strategy would not be a natural action for the Media General properties. Historically, newspapers and broadcast media have competed for the same audience and advertisers’ dollars, and the operators of interactive media regarded TV stations and newspapers as “old economy” relics. Bryan saw that his convergence strategy for creating new revenue sources required the use of the Balanced Scorecard to develop strong teamwork, communication, and cooperation across business lines.

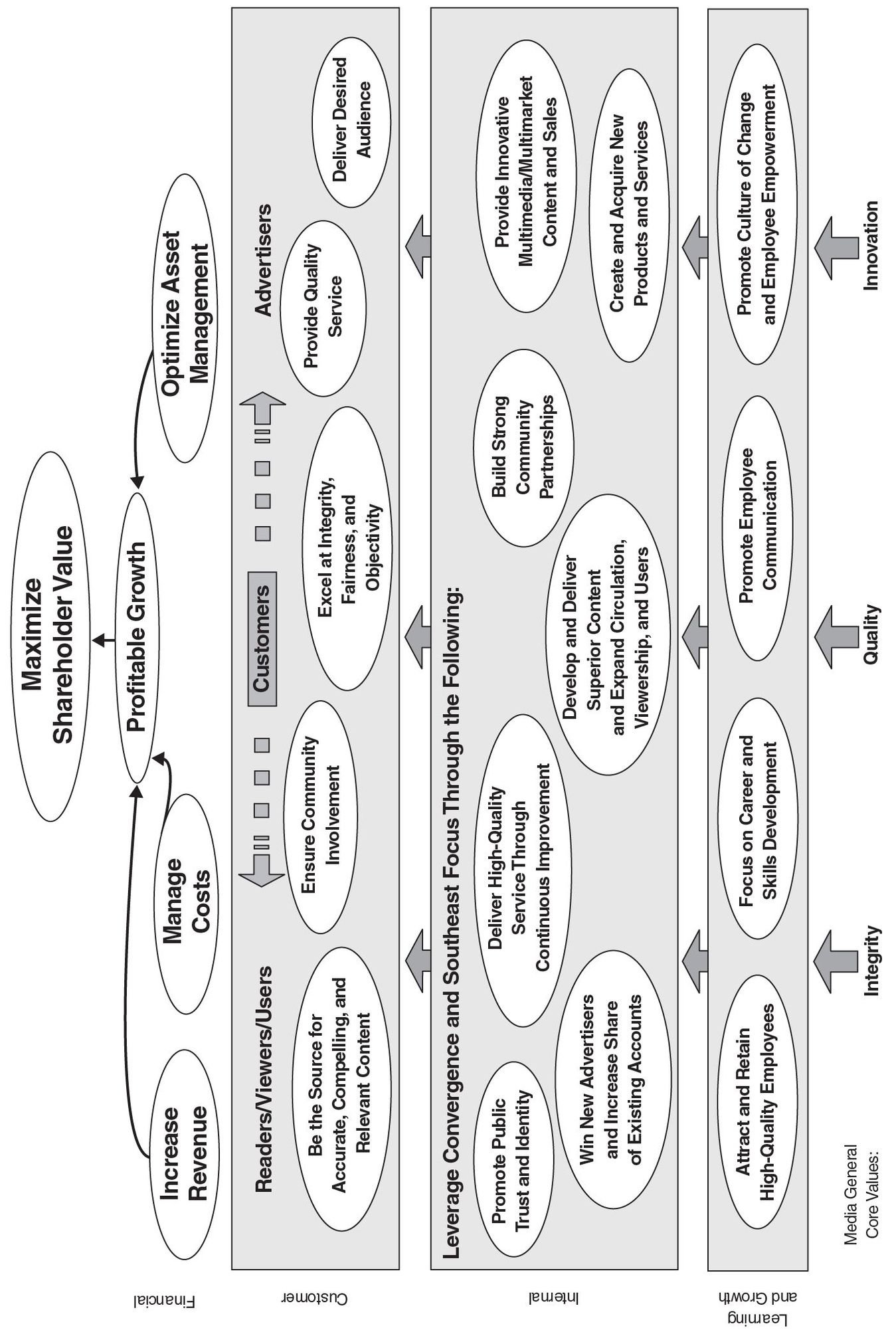

Media General started by crafting its mission statement: “to be the leading provider of high-quality news, entertainment, and information in the Southeast by continually building on our position of strength in strategically located markets.” The corporation continued by developing a corporate Strategy Map (see Figure 3-6) that described the convergence strategy. Here, we identify and analyze several objectives in each perspective, starting with the foundation—learning and growth—to highlight how Media General’s corporate Strategy Map incorporated the convergence strategy.

Learning and Growth

The overall goal of the learning and growth objectives was to have a convergence focus that would guide every employee’s everyday activities. The “focus on career and skills development” objective featured sales personnel receiving training on multimedia and multimarket sales development so that they could effectively sell new multimedia packages to advertisers. The objective “promote culture of change and employee empowerment” involved education to help employees understand the benefits of working as parts of a single regional Media General team rather than thinking, within a silo, as employees of a newspaper, a TV station, or a Web page.

Figure 3-6 Media General Strategy Map

Internal

The objective “develop and deliver superior content” signaled how the newsrooms from all three divisions should work together to jointly develop stories. The goal was to have more stories to share, along with higher-quality products and content delivered in a more timely fashion. The objective “provide innovative multimedia/multimarket content and sales” was a direct convergence objective. Metrics for this objective included the number of targeted (advertiser) convergence accounts successfully sold through cooperative efforts from the three divisions, new nontraditional advertisers gained, and new programs sold.

The company expected that both of these internal process objectives would influence a third, “build strong community partnerships.” The synergies gained when properties in the three divisions worked together, rather than competed, were expected to increase local awareness of Media General’s brand.

Customer

The customer objective “provide quality service” was based on a newly developed online advertiser survey. The survey’s aim was to learn whether Media General’s new value proposition of integrated multimedia content was indeed giving local advertisers additional vehicles to get their message out to the public and generating more consumer traffic to their places of business. The objective “ensure community involvement” tracked customers’ perception of Media General as a strong community citizen. This objective directly measured the scope benefit of Media’s convergence strategy, a larger community presence due to its having multiple properties in the same region.

Financial

Ultimately the success of the corporation’s convergence strategy would be measured by its delivery of improved financial results. The “increase revenue” objective had one measure that identified the convergence revenue that was incremental to revenue earned from the existing, traditional base of properties in the three divisions. It directly measured the increased revenue resulting from the purchase of the new multimedia/multimarket packages by existing advertisers as well as revenues from new advertisers acquired through convergence offerings.

A second measure for this objective tracked growth in traditional advertising revenue; it motivated the three divisions to continue to focus on their core businesses while also contributing to the new convergence business. The objective “manage costs” represented scale economies that the executives expected to gain by consolidating news production among the three divisions, by reengineering processes, and by sharing best practices throughout the three divisions.

Cascading

Once Media General had developed the enterprise Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, each of the properties in the three divisions then developed its individual scorecard. These scorecards reflected the balance between the convergence priorities on the corporate scorecard and each division’s local business situation.

A unique feature of the Media General implementation was a subsequent step to create a Strategy Map and scorecard for each region. Initially, a local, cross-business team consolidated the maps and scorecards from the three divisions in the region. The team then created a regional “convergence” Strategy Map and scorecard to reflect synergy opportunities, and it shared the scorecard with the three properties, asking them to update their local scorecards to reflect convergence objectives in their region (see Figure 3-7).

Results

In 2002, a particularly difficult year in the publishing industry, earnings per share from continuing operations almost tripled on revenue growth of 4 percent. Multimedia advertising packages contributed to a 42.5 percent revenue gain in the interactive media division. Revenue growth increased only slightly in 2003, but income from continuing operations increased more than 10 percent. The publishing division was second in the nation in its peer group of newspapers in total revenue growth, and the interactive media division increased revenues by 60 percent.

SYNERGIES FROM A COMMON CUSTOMER VALUE PROPOSITION

Many corporations generate value by offering and consistently delivering a common customer value proposition throughout their decentralized units. Customers can be assured that they will get the same products, services, value, and buying experience at any corporate unit they transact with.

Figure 3-7 Cascading the Convergence Strategy at Media General

Examples of homogeneous units operating under a corporate structure are branded fast food and restaurant outlets, hotels, gasoline stations, apparel stores, convenience stores, and retail branch banks. A company that operates such retail units brands its strategy with every customer contact at every unit. The enterprise value proposition is to create satisfied, loyal customers by offering a consistent experience, conforming to the corporate quality standards, at each outlet for every customer contact.

The financial perspective of the corporate scorecard identifies the financial metrics used by the company to evaluate the success of its strategy. These are often industry specific, such as same-store sales growth (for retail stores) and revenue per available room (for hotels). Customer objectives relate to creating satisfied, loyal customers from every buying experience. Internal process objectives communicate the importance of having each unit conform to the corporate standard for delivering the customer value proposition, including standards for speed, quality, and friendly service. Learning and growth objectives emphasize retention and development of employees, because the customer’s experience with the company is usually delivered by frontline employees.

Companies in this category have the simplest cascading process. Executives at corporate headquarters decide on the strategy and the value proposition to be offered at each unit. The executives translate the strategy into a Balanced Scorecard of key metrics, which is communicated and applied at every retail outlet.

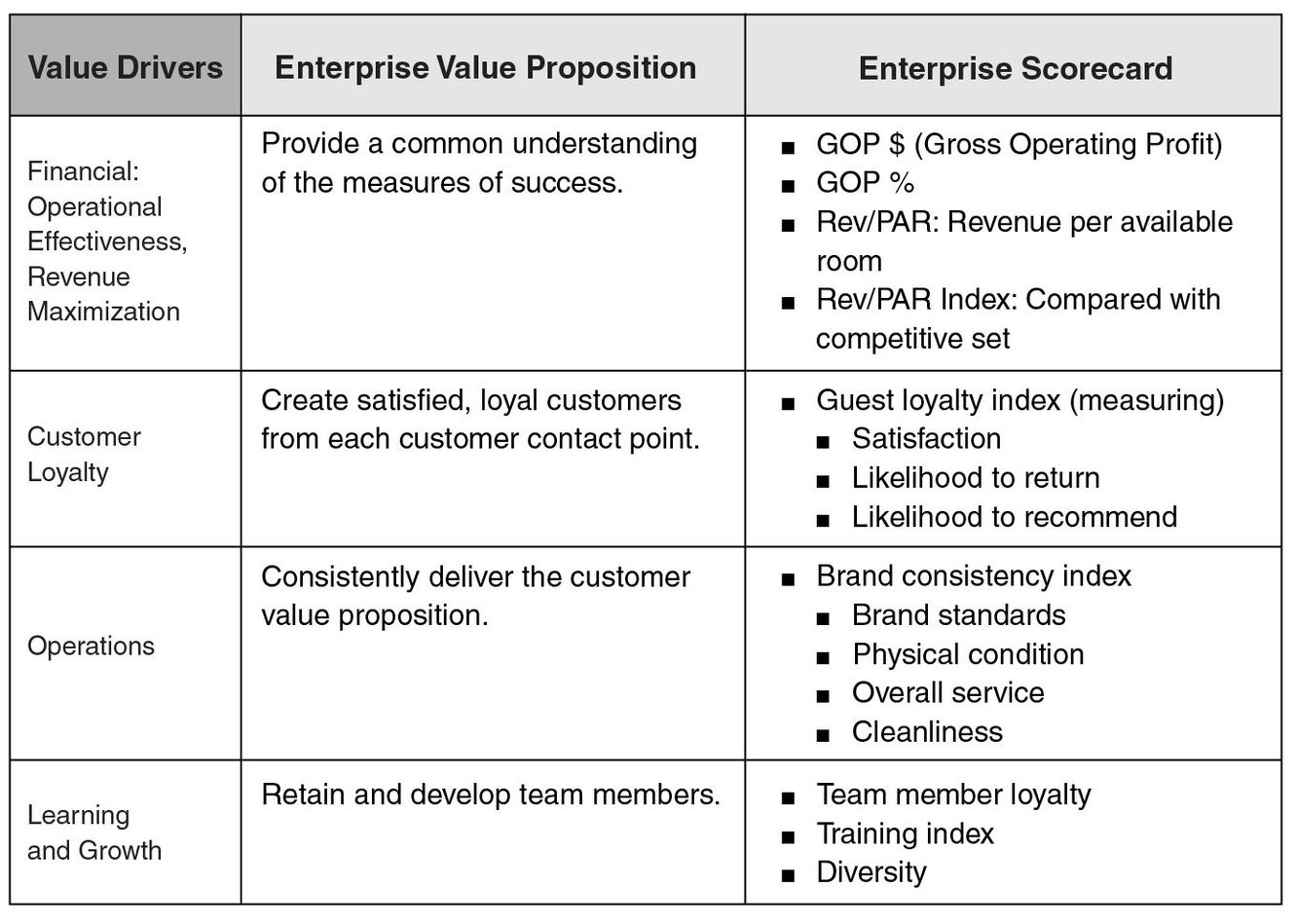

To illustrate this alignment role for the Balanced Scorecard, we present two case studies: from the private sector, Hilton; and from the nonprofit sector, Citizen Schools.

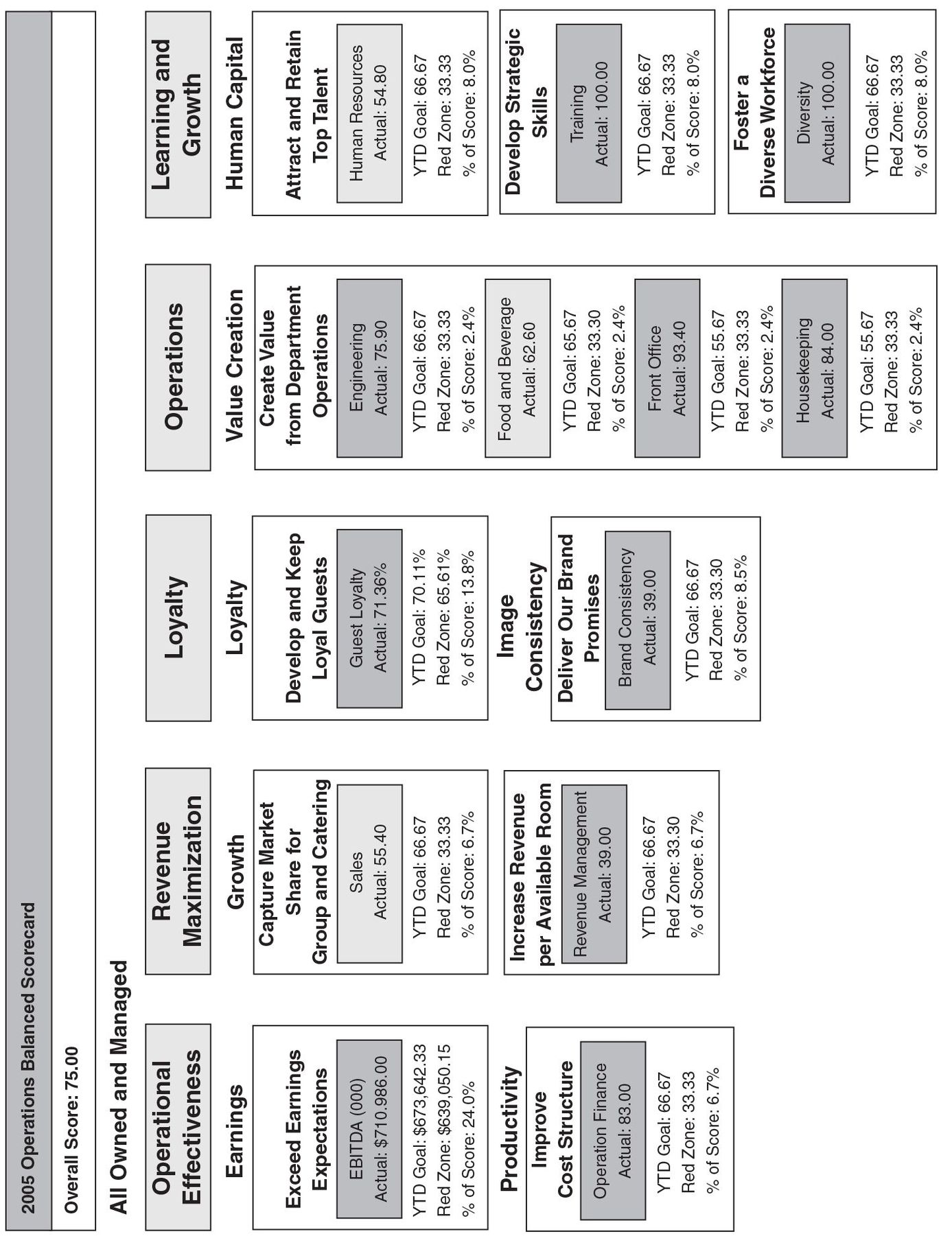

CASE STUDY: HILTON HOTELS

In 2005 Hilton Hotels Family of Brands included over 2,300 owned, managed, and franchised properties, totaling over 360,000 rooms. Hilton initially introduced the Balanced Scorecard Program at its owned and managed hotel properties in 1997, after a period of stagnant performance. At the corporate level, senior executives developed five strategic value drivers (perspectives), and from these value drivers, developed KPIs for the individual SBUs, its hotels (see Figure 3-8). This allowed the hotels to align with the corporate strategic direction while having their own unique KPI measures based on prior year actuals, plus an improvement factor.

Figure 3-8 Case Study: Hilton Hotels

The common scorecard format for each property enabled a clear and consistent message to be delivered throughout the chain. The promise of a brand requires that customers experience the same level of quality and services at each Hilton property, and individual hotel scores would now be benchmarked internally against all Hilton properties. With corporate strategic direction now linked to hotel measures, managers at each Hilton property could then communicate these measures to every team member. Hotel teams built awareness and understanding of the measures into team members’ orientation and training programs, and continually updated the scores on the nine KPI measures so that team members could track current performance and trends. Finally the hotel’s BSC performance was linked to executive pay through bonus plans. And, to make sure the BSC aligned every team member throughout the hotel, all team members at hotels getting all green zones for all nine KPIs shared a portion of an annual $1 million “Go for the Green” award.

From 1997 to 2000, Hilton realized profit margins three percentage points higher than other full-service hotels. This financial performance was achieved through improvements in the revenue per available room (RevPAR) index, customer satisfaction, post-stay loyalty (delivering the highest scores in the company’s history).

By 2004, following the spin-off of gaming hotels and the merger of Promus Hotels (Doubletree, Embassy Suites, Homewood, Hampton Inn) Hilton’s Balanced Scorecard was embedded in a comprehensive performance management program that included planning, budget-goal setting, measurement (BSC), continuous improvement process, operational support, and reward and recognition (see Figure 3-9).

Hilton’s new Performance Management System is Web based, which allows for drill-down capabilities so managers can determine the root causes and detail information behind the numbers to assist in their continuous improvement effort. And Hilton was now using its extensive cross-sectional database to develop statistical linkage among its processes, objectives, and leading/lagging indicators. The indicators helped to identify the relationship between variables, and opportunities for finding root causes of problems, and subsequently measured whether implemented solutions were having the desired effects. Finally, the system allows the scorecard to cascade through the organizational hierarchy from the enterprise, regional, and hotel rollup scorecards, to the department and ultimately to the individual level, optimizing alignment and accountability throughout the organization.

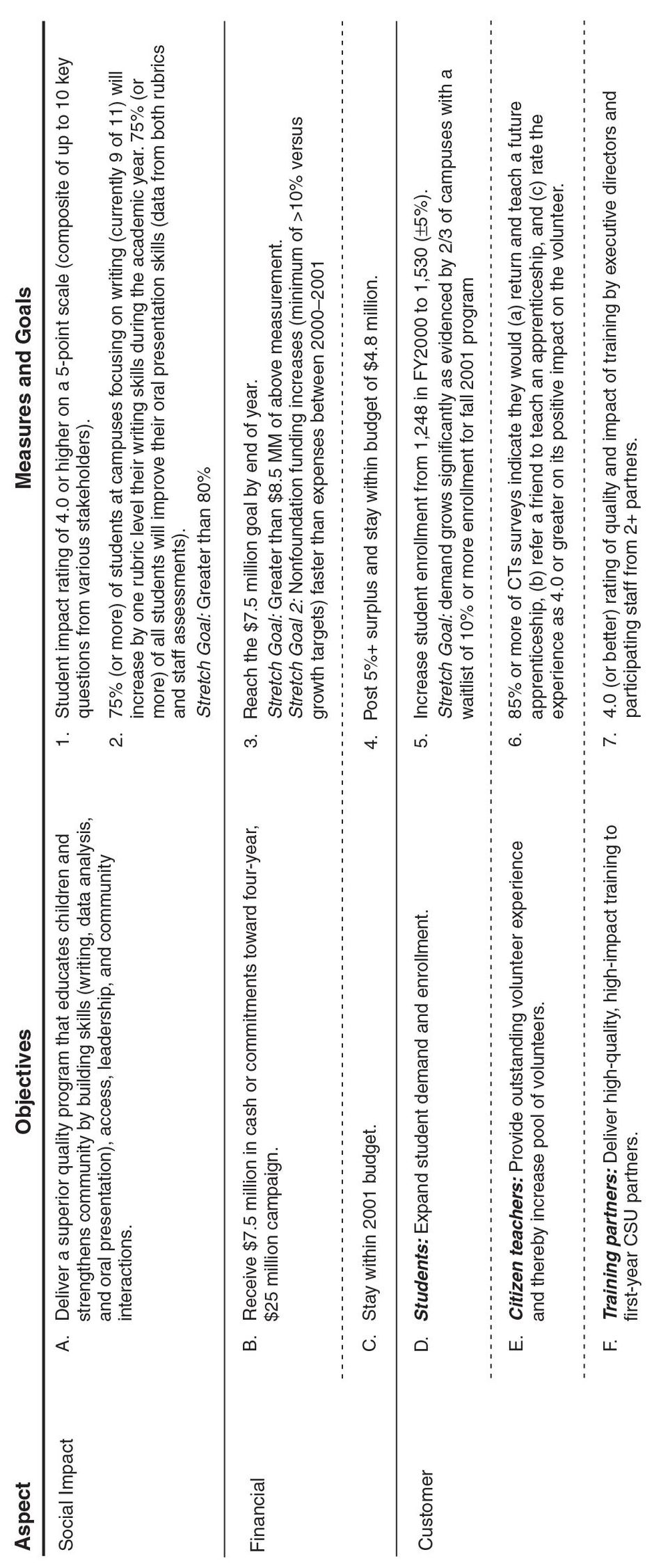

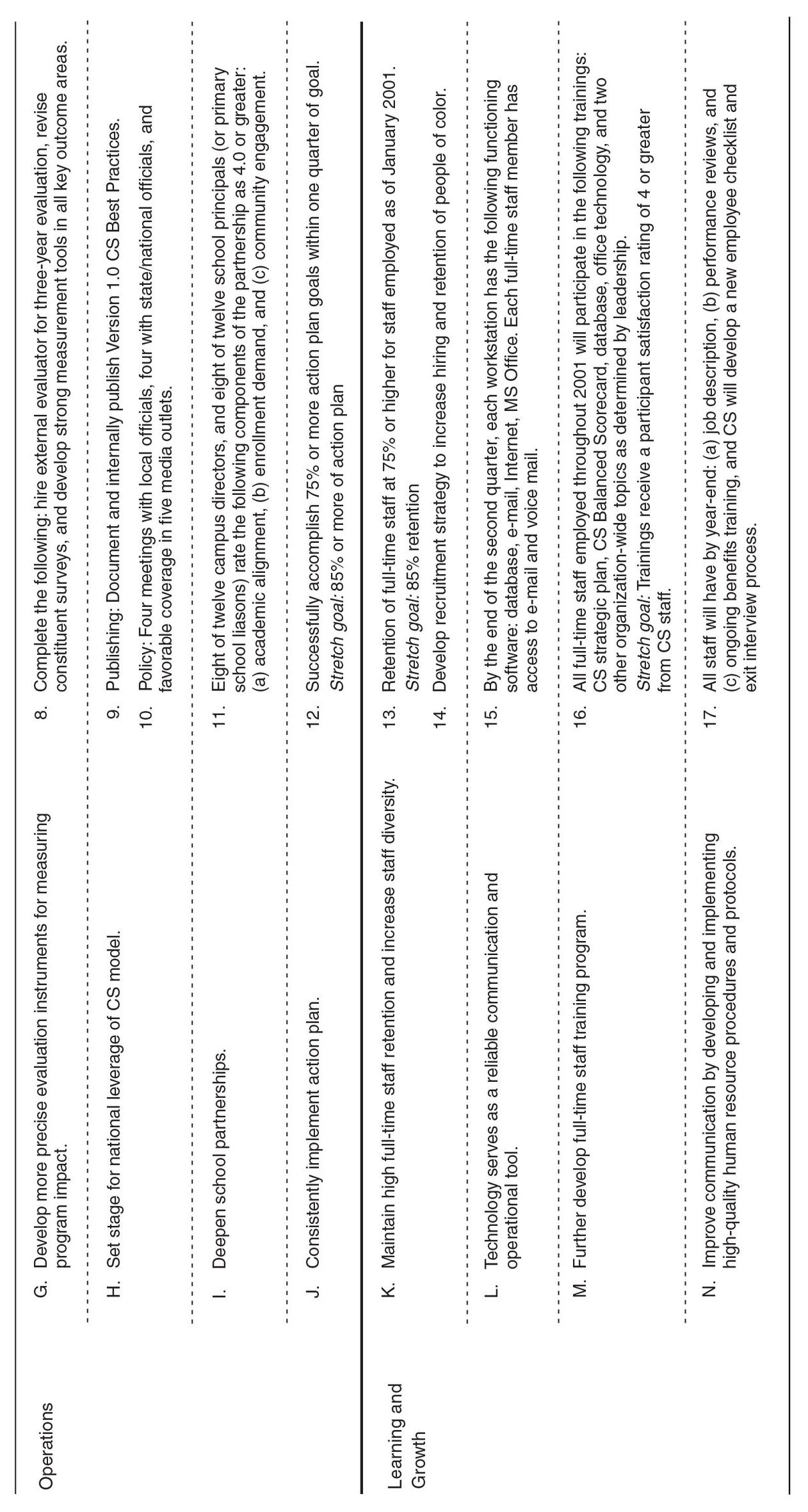

CASE STUDY: CITIZEN SCHOOLS

Citizen Schools, one of the portfolio companies of New Profit Inc. (NPI was discussed earlier in this chapter), is a nonprofit example of this common value proposition model. Citizen Schools operates after-school and summer programs for children aged nine through fourteen in Boston and across the United States. Through apprenticeships with local experts, children learn real-world skills, build self-confidence, and connect with their communities.

Citizen Schools’ Balanced Scorecard (see Figure 3-10) follows the five-perspective framework of New Profit Inc. The scorecard includes measures of students’ academic and social development and provides guidance and feedback for the training and development of staff.

Figure 3-9 Hilton Corporation Balanced Scorecard

Central to Citizen Schools’ strategy is to replicate its model at multiple sites around its Boston home base and to affiliates and franchises that operate throughout the United States. By 2004, Citizen Schools units were operating in six other cities in Massachusetts and in San Jose and Redwood City, California; Houston, Texas; Tucson, Arizona; and New Brunswick, New Jersey. As the organization expands, it uses its Balanced Scorecard template to communicate the common strategy to all sites.

In general, personnel at the new sites are not familiar with the Balanced Scorecard and its terminology. But they all understand the perspectives of social impact and the customer. Citizen Schools uses key BSC measures to communicate performance expectations and to track results at each site. Now that it has more than a dozen sites operating with the same scorecard measures, Citizen Schools benchmarks performance data from all the units and identifies opportunities for best-practice sharing. Having a common measurement and management system is a key ingredient for Citizen Schools in rapidly scaling its operations to a national level while still delivering a consistent experience and value proposition at each newly opened site.

SUMMARY

Even the most diversified enterprise can create value when it operates an internal capital market that is more effective than having each business unit in its portfolio seek its own financing independently from external capital providers. Such enterprises can describe and monitor their objectives for value creation through high-level financial metrics.

Diversified enterprises also create value when they articulate corporate-level themes that brand each operating company with an image and that leverage capabilities related to such objectives as good governance, product quality, customer-focused solutions, community responsibility, or environmental excellence. Customer-based value can be created when diverse business units combine their products and services to offer customers convenient, integrated solutions. Customer-based value also arises when homogeneous, geographically dispersed units give customers a consistent, high-quality buying experience of products or services. In such enterprises, the corporate headquarters articulates the branded, common experience and uses Balanced Scorecards to motivate and monitor the delivery of service throughout its dispersed units.

Figure 3-10 Citizen Schools Balanced Scorecard (FY2001)

NOTES

Private correspondence to Balanced Scorecard Collaborative.

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

T. Khanna and K. Palepu, “Why Focused Strategies May Be Wrong for Emerging Markets,” Harvard Business Review (July–August 1997).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004), 192–195.