CHAPTER ONE

ALIGNMENT A SOURCE OF ECONOMIC VALUE

ON FALL AND SPRING WEEKENDS, we often see eight-person shells racing up the Charles River separating Boston and Cambridge. Although each shell contains strong, highly motivated athletes, the key to their success is that they row in synchronism. Imagine a shell populated by eight highly conditioned and trained rowers, but with each rower having a different idea about how to achieve success: how many strokes per minute were optimal and which course the shell should follow, given wind direction and speed, water current, and a curvy course with multiple bridge underpasses. For eight exceptional rowers to devise and attempt to implement independent tactics would be disastrous. Rowing at different speeds and in different directions could cause the shell to travel in circles and perhaps capsize. The winning crew invariably rows in beautiful synchronism; each rower strokes powerfully but consistently with all the others, guided by a coxswain, who has responsibility for pacing and steering the course of action.

Many corporations are like an uncoordinated shell. They consist of wonderful business units, each populated by highly trained, experienced, and motivated executives. But the efforts of the individual business units are not coordinated. At best, the units don’t interfere with each other, and the corporate performance equals the sum of the individual business units’ performance minus the cost of the corporate headquarters. More likely, however, some of the business units’ efforts create conflicts over shared customers or shared resources, or the units lose opportunities for even higher performance by failing to coordinate their actions. Their combined results fall considerably short of what they could have achieved had they worked better together.

The shell’s coxswain is like a corporate headquarters. A passive coxswain consumes valuable space, weighs down the boat, and detracts from the crew’s overall performance. A superior coxswain, in contrast, understands the strengths and weaknesses of each rower, studies the external environment, and analyzes the competition. The coxswain then determines a clear course of action for the shell and ensures its implementation by coordinating the rowers for optimal performance. The superior coxswain, like a well-led corporate headquarters, adds to the performance of the individual rowers.

ALIGNMENT MATTERS

Each year, the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative selects a few organizations for induction into the Balanced Scorecard Hall of Fame for Strategy Execution.1 These organizations have demonstrated successful implementation of their strategies using a performance management system based on the BSC.

For example, consider Chrysler Group, the U.S. automobile division of DaimlerChrysler, which faced a forecast loss of $5.1 billion in CY 2001. The division brought in a new CEO, who used the BSC to communicate a turnaround strategy involving both cost reductions and future growth through new product development. Despite continued weakness in the U.S. automobile market, Chrysler generated $1.9 billion in profits in 2004 through a combination of great new car introductions and major production efficiencies. Media General, a regional communications company (newspapers, television, and Internet), used the scorecard to align its diverse properties to a new convergence strategy and saw its stock increase 85 percent more than that of its competitors over a four-year period. Korean conglomerate E-Land (retail apparel, hotels, furniture, and construction) doubled its revenues to $1.1 billion between 1998 and 2003 while increasing profits from $8 million to $150 million in the same period.

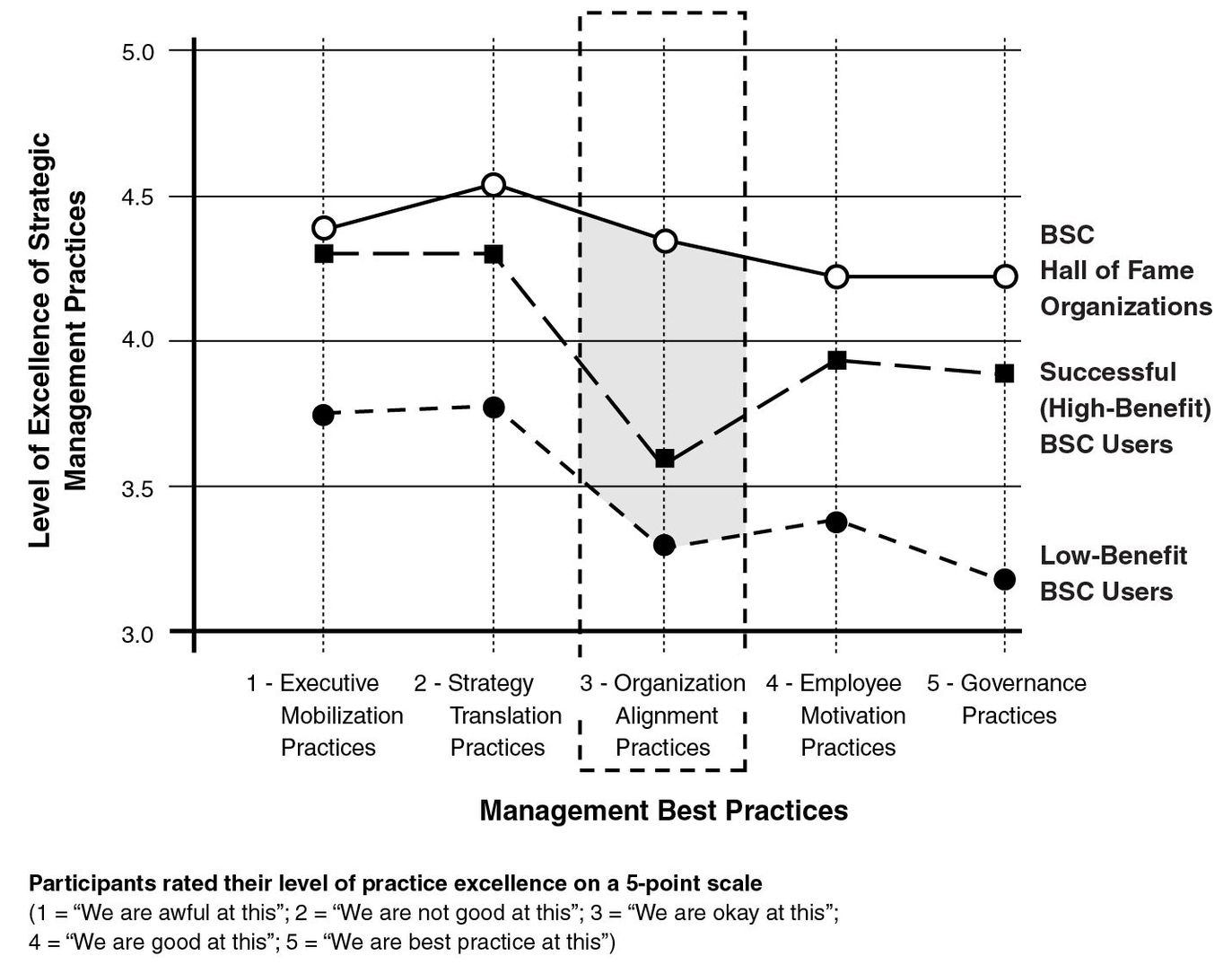

We have studied the specific management practices used by the Hall of Fame organizations and compared their practices with those of two other groups accessed through an online survey: high-benefit users (HBUs) report that they have achieved significant results through use of the Balanced Scorecard, and low-benefit users (LBUs) claim only limited benefits with their scorecard programs. We classified both groups’ management practices along the five key management processes that we have previously identified as important for successful strategy implementation.2

- Mobilization: orchestrating change through executive leadership

- Strategy translation: defining Strategy Maps, Balanced Scorecards, targets, and initiatives

- Organization alignment: aligning corporate, business units, support units, external partners, and boards with the strategy

- Employee motivation: providing education, communication, goal setting, incentive compensation, and training of staff

- Governance: integrating strategy into planning, budgeting, reporting, and management reviews

Figure 1-1 compares the three groups in the levels of excellence they achieved in strategy management practices. The results reveal a strong ordinal ranking. The practice levels of the Hall of Fame organizations exceed those of the other two groups on each strategy management process, and the practice levels of the high-benefit users exceed those of the low-benefit users on each process as well. Higher performance of strategy management practices is associated with high levels of benefits received.

The greatest gap between the practices of Hall of Fame organizations and those of the other two groups occurs for organization alignment. Enterprises enjoying the greatest benefits from their new performance management systems are much better at aligning their corporate, business unit, and support unit strategies, and this indicates that alignment, much like the synchronism achieved by a high-performance rowing crew, produces dramatic benefits. Understanding how to create alignment in organizations is a big deal, one capable of producing significant payoffs for all types of enterprises. Our interest in this subject is natural because surveys of senior executives report that the Balanced Scorecard is one of their top tools to create organizational integration.3

ENTERPRISE-DERIVED VALUE

Aligning organizational units to create value at the enterprise level generally gets less attention than creating value at the business unit (BU) level. Most strategy theories focus on business units, with their distinct products, services, customers, markets, technologies, and competencies. A business unit strategy describes how the BU intends to create products and services that offer a unique, differentiated mix of benefits, called the customer value proposition, to potential customers. If the value proposition is sufficiently attractive, the customer makes a series of purchases that creates value for the business unit. In our previous book we discussed four value proposition archetypes around which business units typically compete.4

Figure 1-1 Relationship Between Managerial Excellence and Level of Benefits

| Best Total Cost | Offer products and services that are consistent, timely, and low cost |

| Product Leader | Offer products and services that expand existing performance boundaries |

| Customer Solutions | Provide a customized mix of products and services, combined with know-how, to solve customers’ problems |

| System Platform | Provide a platform that becomes the industry standard for offering products and services |

Business units develop Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards to help them gain consensus for the strategy among the senior executive team, communicate the strategy to employees so that they can help the organization implement the strategy, allocate resources consistent with the strategy, and monitor and guide the strategy’s performance. All these activities enable the business unit to create value from its customer relationships.

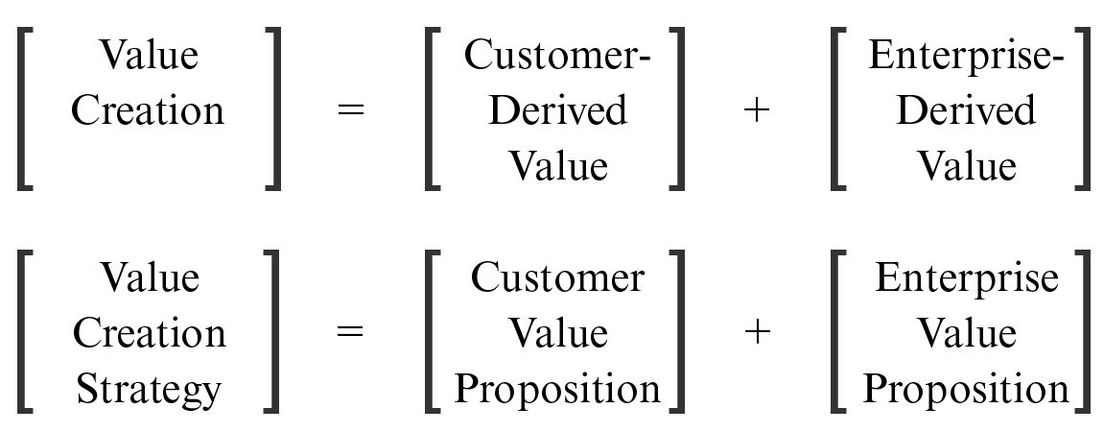

Most contemporary corporations, however, are made up of portfolios of business units and shared-service units. For a corporation to add value to its collection of business units and shared-service units, it must align these operating and service units to create synergy. This is the domain of corporate or enterprise strategy, defining how the headquarters adds value.5 When the enterprise aligns the activities of its disparate business units and its support units, it creates additional sources of value, which we call enterprise-derived value.

For example, a corporation might establish a new sales channel that promotes the cross-selling of products and services offered by its various business units. It might gain economies of scale by sharing an expensive and critical resource, such as a manufacturing plant, a common information system, or a research and development group. Synergies will not occur unless the corporate level plays an active role to identify and coordinate opportunities for integrating the behavior of its decentralized business units. If, however, the corporate headquarters does not create such synergy—or, worse, subtracts from the value created by its collection of operating and service units—investors can rightfully question why the various units are bundled together. Shareholders would receive higher value if the anergystic (opposite of synergistic) corporation would dissolve, leaving them with proportional ownership in the individual operating companies and avoiding the cost and bureaucracy of operating the corporate headquarters.

Corporate strategy describes how an enterprise avoids this fate by creating value greater than that achieved if its individual units were operating autonomously. We refer to the set of specific cross-business objectives intended to create enterprise-derived value as the enterprise value proposition.

Public-sector and nonprofit organizations face similar issues. The Department of Defense must integrate the efforts of large, powerful units (such as the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, and Defense Logistics Agency) that are well funded and have years of autonomous operation and tradition. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police must align its diverse functional and regional units, including national police units dealing with international crime and terrorism, remote units that promote health and safety in aboriginal communities, and contract policing units that provide provinces and municipalities with localized traditional police services. The American Diabetes Association and the Red Cross must unite a multinational network of decentralized units under a common brand and philosophy. Each requires a methodology, such as the Balanced Scorecard and Strategy Map, to clarify, communicate, and facilitate its enterprise role.

The Enterprise Value Proposition

The four-perspective framework of a business unit’s Balanced Scorecard describes how the unit creates shareholder value through enhanced customer relationships driven by excellence in internal processes. These processes are continually improved by aligning people, systems, and culture. The four perspectives are as follows:

| Financial | What are our shareholder expectations for financial performance? |

| Customer | To reach our financial objectives, how do we create value for our customers? |

| Internal Process | What processes must we excel at to satisfy our customers and shareholders? |

| Learning and Growth | How do we align our intangible assets—people, systems, and culture—to improve the critical processes? |

Each of these four perspectives is linked in a chain of cause-and-effect relationships. For example, a training program to improve employee skills (the learning and growth perspective) improves customer service (internal process), which, in turn, leads to greater customer satisfaction and loyalty (customer) and, eventually, increased revenues and margins (financial).

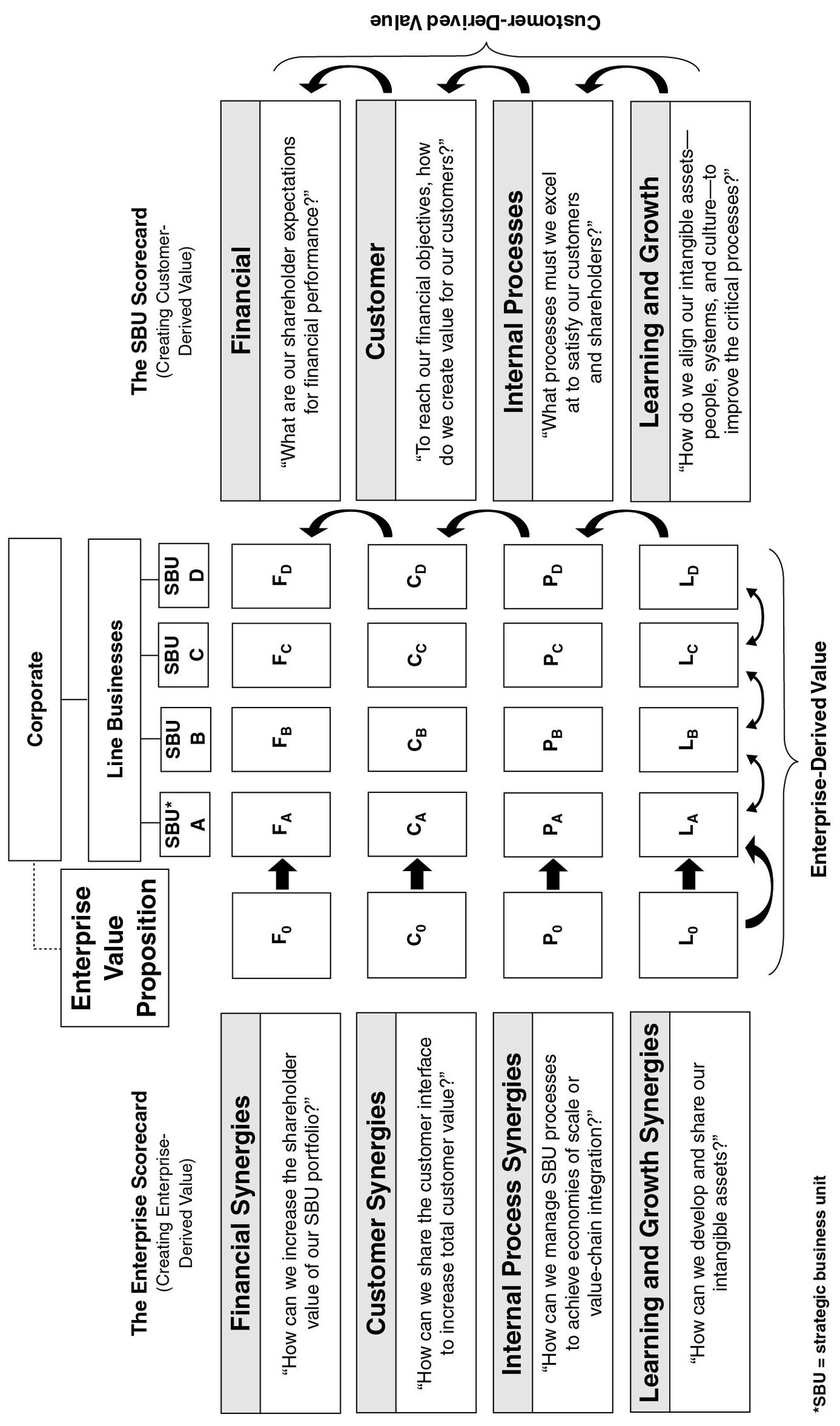

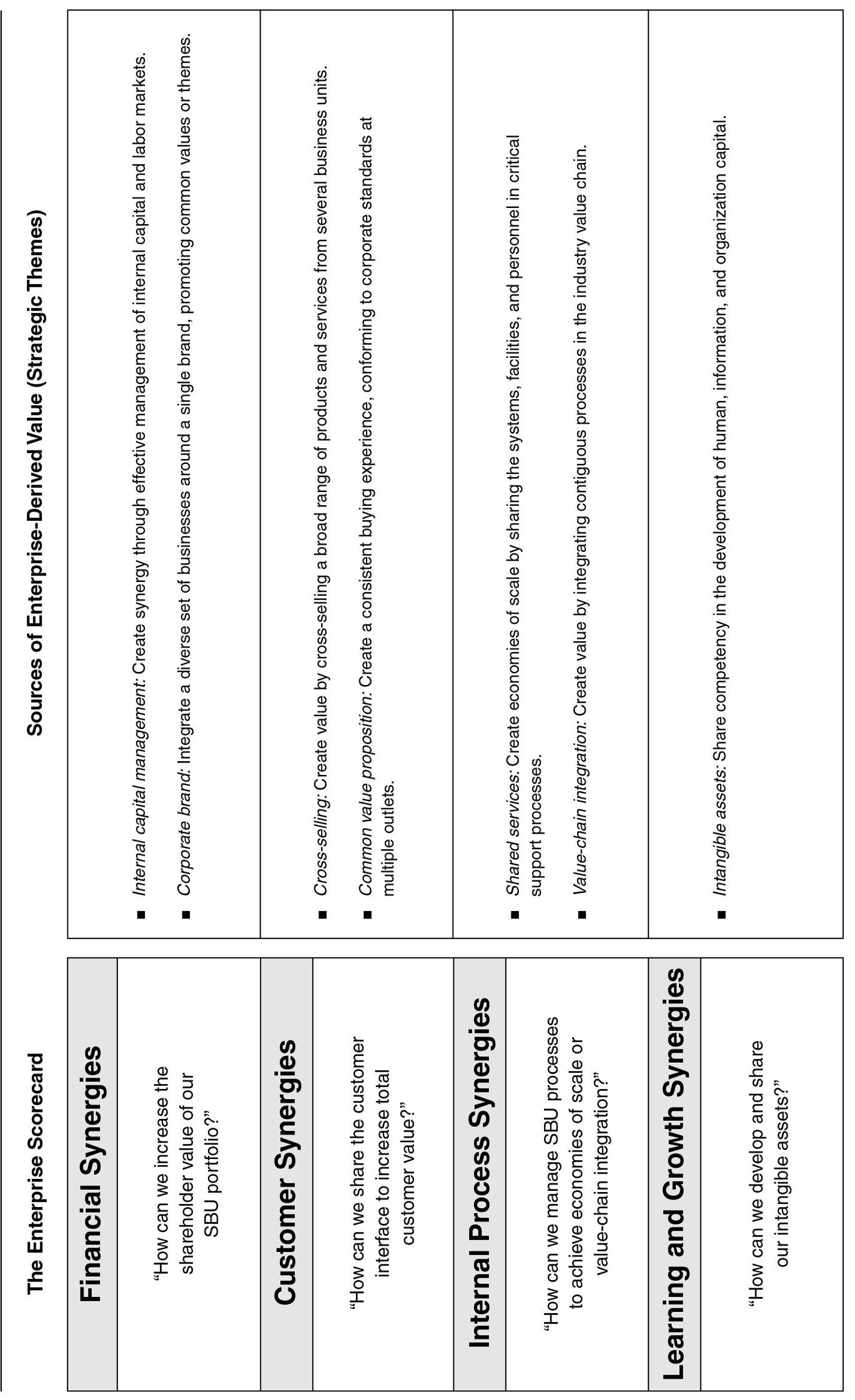

The four-perspective framework for business unit strategies turns out to extend naturally for developing an enterprise Balanced Scorecard (see Figure 1-2). The corporate headquarters does not have customers, nor does it operate processes that make products or services. Customers and operating processes are within the domain of the business units. The corporate headquarters aligns the value-creating activities of its business units—enabling them to create more benefits to their customers or to lower total operating costs—beyond what they could achieve by themselves if they were operating independently. Thus, the objectives in the four perspectives of the enterprise Balanced Scorecard should answer the following questions.

Financial: How Can We Increase the Shareholder Value of the Business Units in Our Strategic Business Unit (SBU) Portfolio?

Corporate financial synergy revolves around issues such as where to invest, where to harvest, how to balance risk, and how to create an investor brand. The corporate headquarters in holding companies and highly diversified corporations (such as Berkshire Hathaway, FMC Corporation, and Textron) creates value mainly by its superior ability to allocate capital among its operating units. The corporate value to these diversified enterprises comes from operating an internal capital market that is more effective and efficient than if each autonomous company were an independent and publicly owned company.

Other corporations, in addition to striving for financial synergies from superior resource allocation and governance processes, play an active role in creating synergies among the three other Balanced Scorecard perspectives.

Customer: How Can We Share the Customer Interface to Increase Total Customer Value?

A satisfied customer is a precious asset. The goodwill generated by a positive customer relationship translates into the potential for repeat purchases and an extension of the relationship to other company products and services, particularly those packaged under the same brand. Companies with homogeneous retail outlets—such as retail banks, stores, and franchisers like Hilton Hotels and Wendy’s—seek to promote standardization throughout their dispersed units to deliver a common, consistent customer experience at every location, one that reinforces and enhances the corporate brand.

Figure 1-2 Building the Entreprise Scorecard

In more diversified corporations, a single business unit may initiate a customer relationship and develop it modestly, but ultimately the unit may be limited by the breadth of its products or services. Other business units in the corporation can enhance the relationship by offering complementary products and services to the same customer. A producer of medical instruments, for example, may have satisfied and loyal customers for its range of products. But it can generate an additional—and perhaps more profitable and certainly more stable—source of revenue through post-sales service and maintenance performed by the company’s field services business unit. By expanding the marketing message and redesigning the selling process, corporations can bring the products of several business units to the customer, thus increasing revenue per customer through cross-selling.

For example, the former strategy of Northwestern Mutual, a financial services company, was based on providing superior life insurance through a single sales force of insurance specialists. The company’s new strategy expanded on this base by adding a full range of investment products and advisory services to address the needs of its customers for financial protection, capital accumulation, estate preservation, and asset distribution. Northwestern Mutual created a network of specialists to assist the insurance sales force with the advice and support required to serve customers and cross-sell this broader set of services. The corporate role was to create value by broadening the set of services available to customers, who were now exposed to the knowledge of the account team as well as the capabilities of multiple products that were now linked to create a more complete solution. The corporation created teamwork across business units that previously had operated autonomously.

Internal: How Can We Manage SBU Processes to Achieve Economies of Scale or Value-Chain Integration?

Large organizations have opportunities to create economies of scale to enhance their competitive advantage and shareholder value. The purchasing and distribution processes of Wal-Mart (private sector) and Defense Logistics Services (public sector) operate at a scale that rivals the GNPs of small countries. Every multiunit corporation can create scale economies by examining common processes required by its multiple business units.

For example, one corporate department in a retailer such as The Limited contracts for and manages real estate used by all retail outlets. Another corporate-level department negotiates supplier relationships for all the business units. Automobile manufacturers, such as Daimler Chrysler, coordinate the design and development of new products on a global basis. In our earlier books, we described how the marine engineering division of Brown & Root created value by integrating the offerings of its previously independent engineering, design, fabrication, installation, and logistics business units so that it could supply a complete, turnkey solution to customers.

Learning and Growth: How Can We Develop and Share Our Intangible Assets?

Perhaps the greatest opportunity for a beneficial headquarters role is to develop and share critical intangible assets: people, technology, culture, and leadership. Professional service organizations such as SAS Institute (software), Accenture (consulting), and Schering (pharmaceuticals) consciously manage the movement of ideas throughout their enterprises. Citicorp and Goodyear were pioneers in creating a global culture by rotating a cadre of executives in their worldwide offices to support their strategies for global expansion. Organizations like British Petroleum (BP) have centralized IT organizations that share the sophisticated, specialized knowledge of IT professionals with diverse organizational units. Intangible assets have become a new force in business strategy. They present an opportunity, and a mandate, for headquarters offices to manage them in a way that creates synergy and sustained competitive advantage.

Figure 1-3 summarizes various sources of enterprise-level synergies, organized by the four perspectives of an enterprise Balanced Scorecard. We describe and illustrate this structure in more detail in Chapters 3 and 4, where we describe successful private, public, and nonprofit enterprise applications.

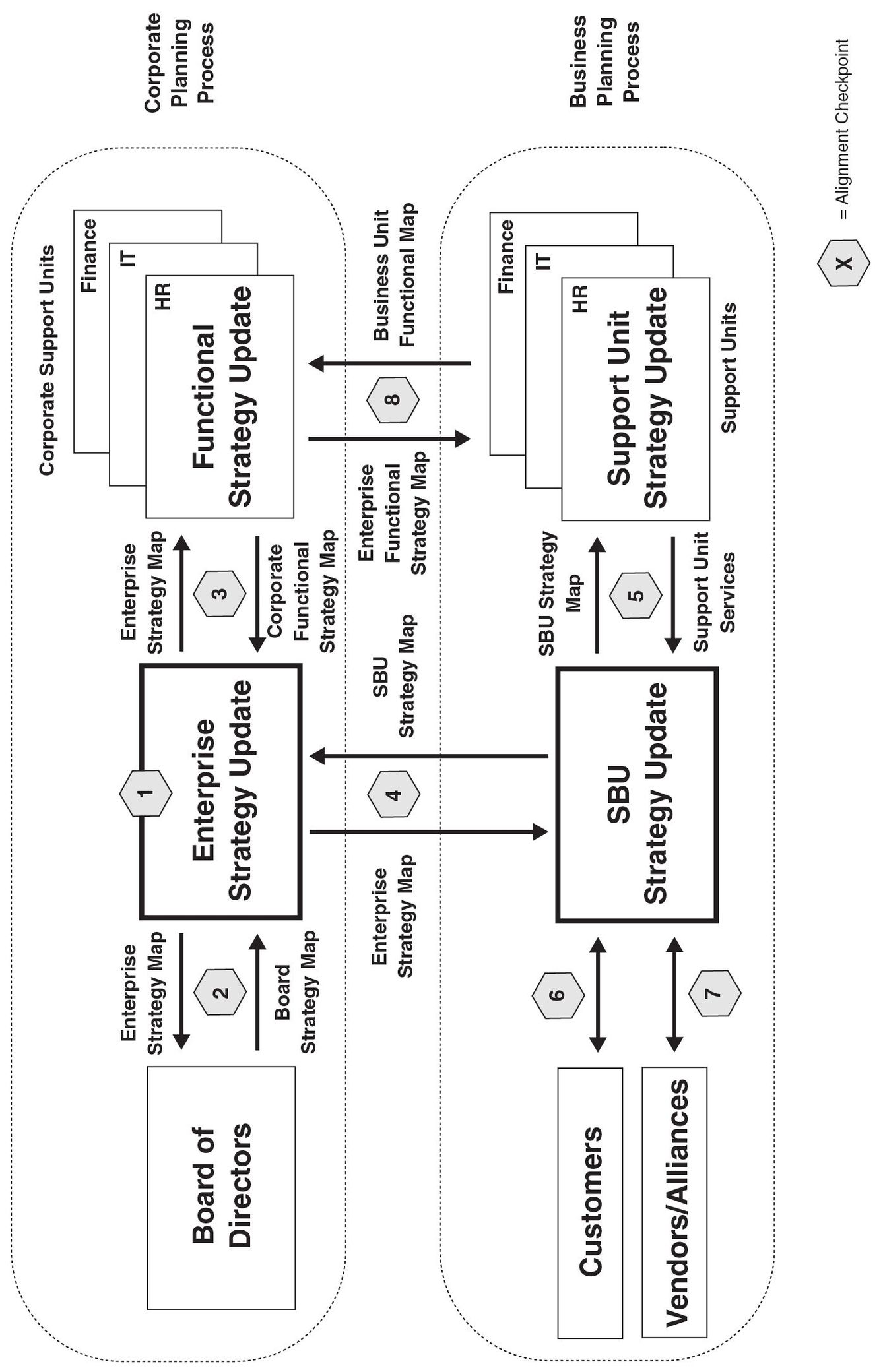

THE ALIGNMENT SEQUENCE

Figure 1-4 shows a typical sequence used to create enterprise-derived value. The process starts when the corporate headquarters articulates an enterprise value proposition that will create synergies among operating units, support units, and external partners. The enterprise Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard articulate and clarify corporate priorities and clearly communicate them to all business and support units.

Figure 1-3 Sources of Enterprise Synergy

Figure 1-4 Building Alignment into the Planning Process

Aligning Enterprise Headquarters with Operating Units

After the corporate headquarters develops its strategy and value proposition, each business and support unit develops its long-range plan and Balanced Scorecard to be consistent with the enterprise scorecard. The process helps business units balance their challenging tasks. They, of course, must be formidable competitors in their local markets. They often choose their targeted customers and the value proposition to be offered to customers and then develop their people, systems, and culture to enhance internal operating processes, customer management processes, and innovation processes that deliver value to customers and their corporate parent. Business units must also contribute to corporate-level synergies, incorporating corporate themes, servicing corporate customers, and integrating and coordinating with other business units for additional sources of value creation. Business unit Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards must reflect both local excellence and corporate contribution. We discuss such alignment in Chapters 3 and 4.

Aligning Internal Support and Service Units

Next, shared-service units, such as human resources, information technology, finance, and planning, develop their long-range plans and Balanced Scorecards to support the strategies of the business units and enterprise priorities. For example, the enterprise value proposition may require that the human resource department create synergy by developing new programs to recruit, train, retain, and share key personnel throughout all organizational units. If enterprise strategy dictates an emphasis on risk reduction from terrorism, for example, then the information technology department can lead a disaster planning and prevention program that applies to all units. To be effective, internal service units must understand the enterprise strategy and must align their activities with that strategy.

Traditionally, however, companies have treated their service units as discretionary expense centers. Each year, during the budgeting process, they decide how much they can spend on each service unit, and then, during the subsequent year, they monitor service units’ actual expenses against budgeted amounts. Treating these units as discretionary expense centers does little to align them to serve their customers: the internal business units and the corporate headquarters. Creating Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards for service units enables companies to create incremental enterprise value through alignment of the units’ customer, process, and learning and growth objectives with the business unit objectives. The process transforms service and support groups from expense centers to strategic partners. Chapter 5 describes the process of creating Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards that link service unit strategies with corporate and business unit strategies.

Corporations have followed various paths to align business and shared-service units. Some have started by defining strategy at the headquarters level and then cascading this strategy to all operating and service units. This logical and orderly process has occurred within some highly structured, hierarchical enterprises, such as the U.S. Army and Petrobras, the Brazilian national oil, gas, and energy company. Alternatively, many if not most corporations have started their Balanced Scorecard programs in a single business unit or even a service group. These corporations did not want the BSC program to be viewed as one led and mandated by headquarters. They deliberately started the program bottom-up, postponing the definition of the enterprise value proposition and enterprise-wide coordination until all the operating units were on board with the new management system. We discuss these various implementation paths in Chapter 6.

Aligning External Organizations

Beyond the alignment of internal business and service units, an enterprise can exploit additional alignment opportunities by formulating plans and scorecards that define relationships with its board of directors and external partners, such as customers, suppliers, and joint ventures. The CEO and CFO can use the Balanced Scorecard to enhance corporate governance and to improve communication with shareholders. Companies align their boards of directors with the strategy by making the enterprise and business unit Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards the board’s central information resource. Some companies go further, working with their boards to construct Strategy Maps and scorecards for the boards themselves. The map and scorecard describe the board’s objectives for investors, shareholders, regulators, and the community, define the critical board processes that must be performed well to deliver on constituents’ expectations, and identify the skills, information, and culture required of the board and its deliberations.

Once the board has become comfortable with the description and measurement of strategy in the enterprise Balanced Scorecard, the CEO and CFO can use the enterprise BSC to structure communication and disclosure with shareholders. Several companies are communicating their Strategy Maps in annual reports to shareholders and are using BSC measures as the framework for discussions and conference calls with analysts. Effective governance, disclosure, and communication reduce the risk faced by investors when they entrust their capital to company managers, and thereby lower the company’s cost of capital. We discuss these applications in Chapter 7.

Building a scorecard with an external partner—a key customer, supplier, or joint venture partner—provides another opportunity to create value through alignment. The process enables the senior managers of the two entities to work together to reach a consensus about the objectives for the relationship. The process also builds understanding and trust across organizational boundaries, leading to lowered transaction costs and reduced misalignment between the two parties. And the scorecard itself provides the explicit contract by which interorganizational performance will be measured. Without a Balanced Scorecard, external contracting focuses on financial measures, such as price and cost. The scorecard provides a more general contractual mechanism that allows the venture to explicitly incorporate measures of relationship, service, timeliness, innovation, quality, and flexibility, as well as cost and price, as we discuss in Chapter 8.

MANAGING ALIGNMENT AS A PROCESS

Each of the activities we have identified is an opportunity to create synergy and value. Most organizations attempt to create synergy, but in a fragmented, uncoordinated way. They do not view alignment as a management process. When no one is responsible for overall organization alignment, the opportunity to create value through synergy can be missed.

To create synergy, we require more than a concept and a strategy. The enterprise value proposition defines the strategy for value creation through alignment, but it doesn’t describe how to achieve it. The alignment strategy must be complemented with an alignment process. The alignment process, much like budgeting, should be part of the annual governance cycle. Whenever plans are changed at the enterprise or business unit level, executives likely need to realign the organization with the new direction.

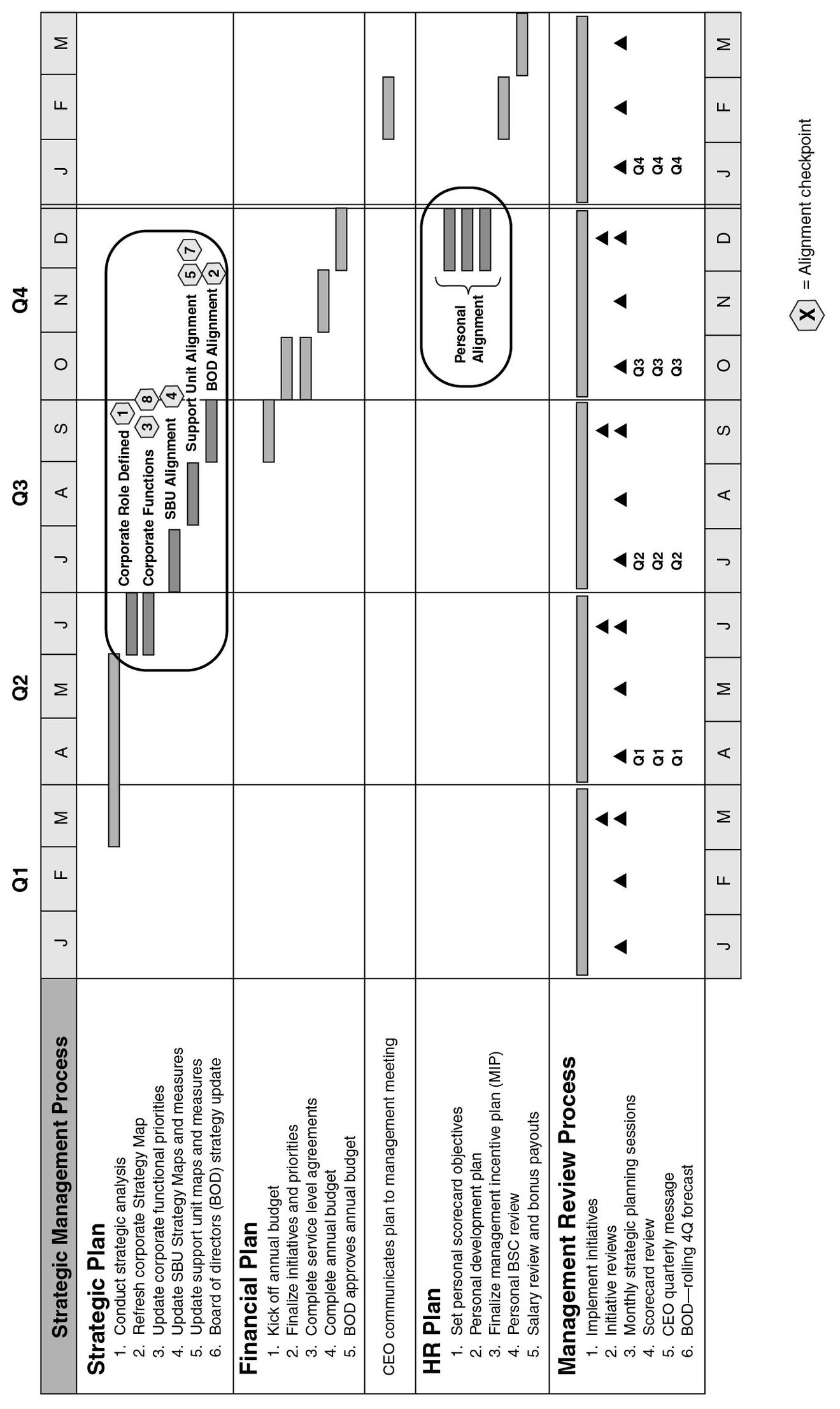

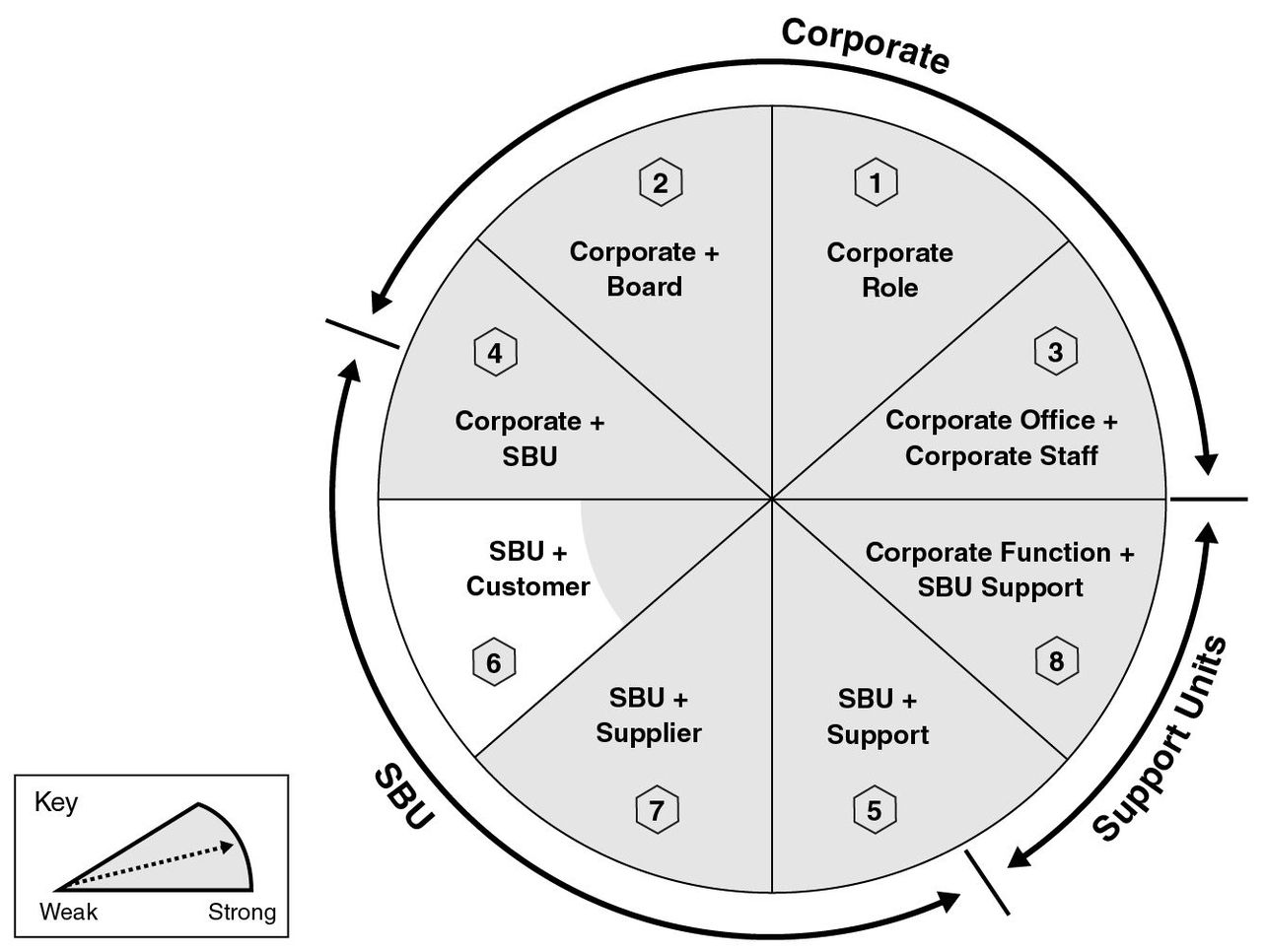

The alignment process, of necessity, should be cyclic and have a top-down bias. The targeted corporate synergies should be defined at the top and realized in the business units. Just as the CFO coordinates the budgeting process, a senior executive should coordinate the alignment process—a responsibility for the Office of Strategy Management (OSM).6 The annual planning process provides an architecture around which the alignment process can be executed. Following are the eight alignment checkpoints (see Figure 1-4) for corporate, business units, and support units of a typical multibusiness organization to hit during the annual planning process.

- Enterprise value proposition: The corporate office defines strategic guidelines to shape strategies at lower levels of the organization.

- Board and shareholder alignment: The corporation’s board of directors reviews, approves, and monitors the corporate strategy.

- Corporate office to corporate support unit: The corporate strategy is translated into those corporate policies that will be administered by corporate support units.

- Corporate office to business units: The corporate priorities are cascaded into business unit strategies.

- Business units to support units: The strategic priorities of the business units are incorporated in the strategies of the functional support units.

- Business units to customers: The priorities of the customer value proposition are communicated to targeted customers and reflected in specific customer feedback and measures.

- Business support units to suppliers and other external partners: The shared priorities for suppliers, outsourcers, and alliance partners are reflected in business unit strategies.

- Corporate support: The strategies of the local business support units reflect the priorities of the corporate support unit.

Using these eight checkpoints as a point of reference, an organization can measure and manage the degree of alignment, and hence the synergy, being achieved across the enterprise. Organizations that master this process can create competitive advantages that are difficult to dislodge. In Chapter 9, we discuss this ongoing process of sustaining alignment. It requires the modification of existing management processes so that they stay focused on identifying and capturing corporate-level synergies.

Although it is not strictly part of organizational alignment—the primary focus of this book—the enterprise must also align its employees and management processes with the strategy. Having aligned and integrated strategies at all organizational units yields little if employees are not aware of the strategy and are not motivated to help their organizational unit implement it. Enterprises must have active policies to communicate, educate, motivate, and align employees with the strategy. They must also align their ongoing management processes—for resource allocation, target setting, initiative management, reporting, and reviews—with the strategy. In Chapter 10, we discuss these additional alignment processes.

CASE STUDY: SPORT-MAN INC.

We illustrate many of the alignment issues with a disguised case study, Sport-Man Inc. (SMI). The company founded in 1925 to manufacture and market men’s work boots. Its early success was attributed to a classic waterproof, lace-up boot that became the standard for workers in construction, farming, and other professions that require strenuous outdoor labor. SMI built a successful national sales base from its headquarters in Massachusetts by establishing channels with large department and specialty shoe stores.

During World War II, SMI received a large contract from the U.S. Army that put its combat boots on the feet of more than two million soldiers. Its success carried into the postwar boom economy. Building on the Sport-Man brand, the company added a line of hiking boots and became more aware of opportunities for growth in the leisure market. In the 1960s, it added a line of men’s casual shoes sold through company-owned retail stores. The 1970s saw a diversification into men’s clothing, a new line of business (LOB) that focused on outdoor clothing for work or play. The clothes soon became synonymous with the “hunter look.” Capitalizing on the growth of suburban malls, SMI soon had more than one hundred retail stores, mostly in the Northeast. During the 1980s, it took the product nationwide, with outlets in more than four hundred malls.

Growth slowed in the mid-1990s. Sport-Man was a great brand, but its market for men’s outdoor shoes and clothing had become saturated. A comprehensive strategy review revealed that the Sport-Man brand could be extended to other apparel lines. Furthermore, its retail footprint in major malls throughout the United States provided an excellent channel for opening new stores for the new product lines. The new retail stores could be located in space contiguous to existing Sport-Man stores to make for convenient cross-selling opportunities with existing customers. Finally, SMI’s competency, developed over the forty-year postwar period, in sourcing products from factories in Europe and Asia would allow rapid growth in its new apparel lines, as well as permit significant cost economies.

Thus, the company embarked on its first major diversification program in thirty years by broadening its offerings under the Sport-Man brand. The specifics of the strategy were as follows:

- Add two new lines of business to complement the two current lines of men’s shoes and men’s outdoor clothing:

- A new LOB of men’s casual clothing

- A new LOB focused on sporting goods: clothing, athletic shoes, and equipment

- Achieve distribution synergies by sharing real estate in the four hundred malls that SMI already occupies.

- Share customer lists and credit cards with the new businesses.

- Share the company’s competency in product purchasing.

- Share key management skills with the new LOBs.

Financially, SMI had dual objectives: maintain market share in its core outdoor shoes and clothing product lines and grow the new LOBs to a similar share over the next five years. SMI would harvest cash from its mature businesses to invest in the growth of the new businesses.

SMI’s executives recognized that this strategy required extraordinary alignment and teamwork throughout the business lines. They wanted customers to view each brand as a stand-alone business, but they wanted the business units to cooperate by redistributing cash among them and sharing customer lists, credit cards, real estate, vendors, technology, key employees, and knowledge. With the exception of real estate, current businesses had been allowed to manage themselves independently, so the teamwork required by the new strategy would be a significant change.

SMI management turned to the Balanced Scorecard to help create the necessary organization alignment in the following ways:

- Clearly define corporate’s strategy for each of the business units and, in particular, how they would work together to create synergy.

- Align the business units with the corporate strategy.

- Align the support units with the business units.

- Create a governance process to ensure that alignment is perpetually maintained.

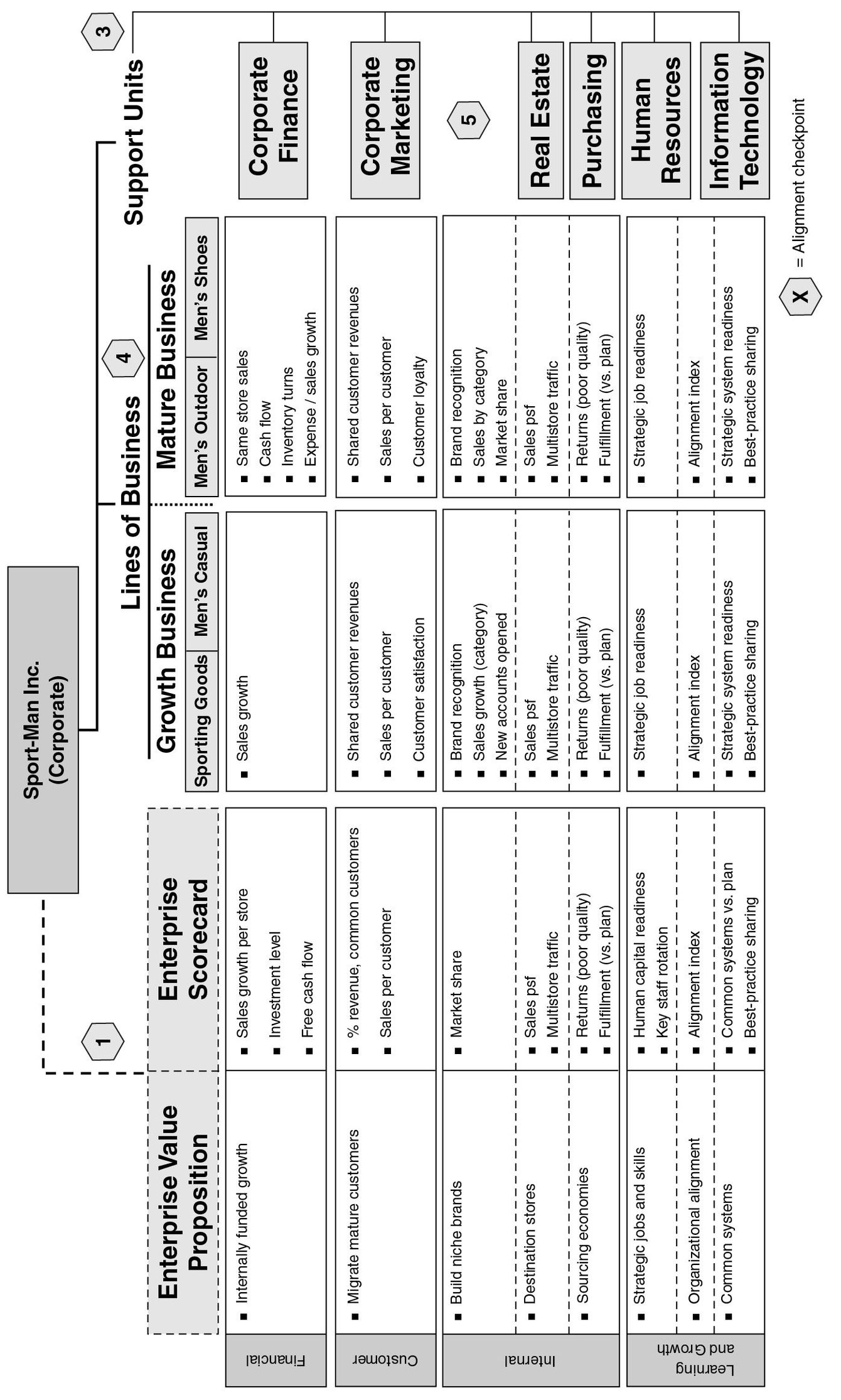

Figure 1-5 shows the first step in this process: the creation of the enterprise scorecard, which describes how synergy will be created. Financial synergy at SMI will be achieved by using the surplus cash flow from the mature businesses to invest in the growth of the new businesses. The corporate measure, sales growth per store, emphasizes that existing stores must participate in normal industry growth while the new stores experience targeted revenue growth. The corporate scorecard also measures the amount of cash flow generated and invested.

Figure 1-5 The Entreprise Scorecard at Sport-Man Inc

The customer synergy comes from sharing SMI’s current customer base with the new businesses. The corporate customer measure, percentage of revenue from common customers, monitors this objective directly, and annual growth in sales per customer emphasizes the importance of cross-selling across product lines.

SMI expected three sources of internal process synergies: (1) using a dominant product category to attract the customer into the store (measured by the category market share); (2) sharing real estate in malls by building clusters of SMI stores and brands (measured by sales per square foot and multistore traffic); (3) purchasing economies of scale (measured by returns and order fulfillment).

Finally, learning and growth synergies would be achieved by rotating experienced professionals to key jobs in the new companies (key staff rotation ), by sharing computer systems (common systems versus plan) and knowledge (best-practice sharing), and, finally, by creating full organization alignment (alignment index).

This enterprise scorecard captures the essential elements of the overall strategy (alignment checkpoint 1). It provides SMI with the top-down guidance from corporate to the business and service units that needs to be reflected in their strategic planning.

Figure 1-6 shows how the business units translate the corporate scorecard into their own business unit scorecards (alignment checkpoint 4). The primary distinction is between the mature businesses and the growth businesses.

From a financial perspective, the mature businesses are expected to generate positive cash flow by maintaining their revenues (same-store sales) and improving productivity (inventory turns and expense growth). The corporate objective from the customer perspective requires the sharing of customers across business units. All businesses measure the same objectives: shared customer revenues and sales per customer. The mature businesses will focus on customer loyalty, whereas the new businesses will emphasize customer satisfaction, a precondition for customer loyalty.

In the internal process perspective, all business units monitor their brand recognition in the marketplace. They also monitor sales and market share in targeted categories. The growth businesses focus more on the acquisition of new customers, measuring new credit card accounts. All business units monitor the same measures regarding sourcing: returns (surrogate for poor quality) and order fulfillment.

Objectives and measures for the learning and growth perspective are the same for all business units, reflecting the sharing of people (strategic job readiness), technology (strategic system readiness), and knowledge (best-practice sharing). The alignment index measures the extent to which the goals of corporate are formally aligned with those of the business units. For example, 87 percent of the measures on the corporate scorecard appear directly on the business unit scorecards. Two measures are unique to corporate: (1) investment level, a measure of how much is being invested in the growth businesses, and (2) key staff rotation, which measures the extent to which corporate is facilitating the movement of key staff. The strategic job readiness measure in the business units reflects the success from such employee mobility. Approximately 80 percent of the measures on the business unit scorecards are held in common. This reflects not only the similarities of the business units but also the significant amount of sharing occurring across the business units.

Figure 1-6 Corporate and SBU Alignment at Sport-Man Inc

The corporate service units help the business units execute the corporate priorities (alignment checkpoint 3). For example, the key staff rotation objective would require a program run by the corporate human resource department to select, cultivate, and place the employees.

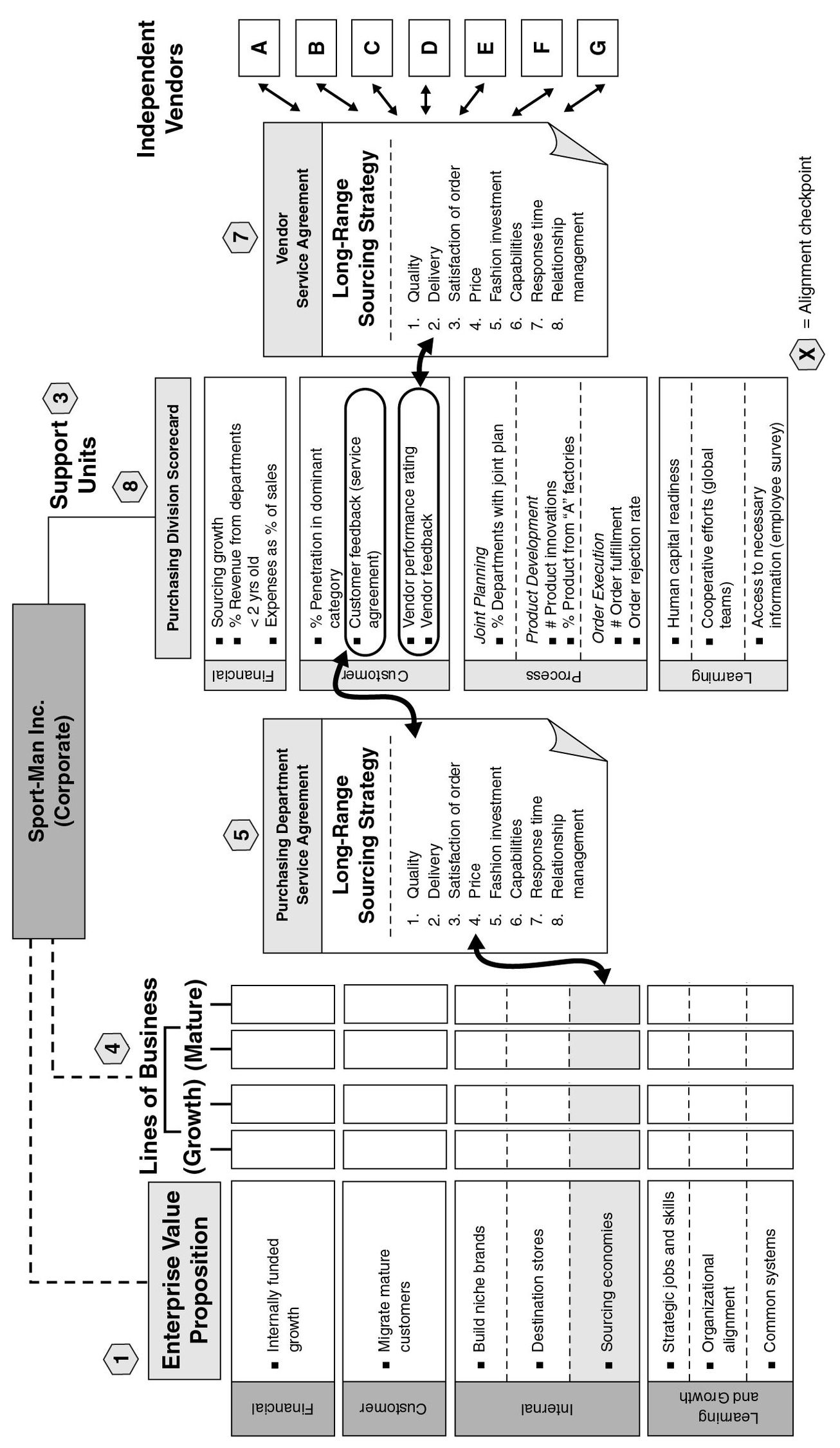

Figure 1-7 describes the Balanced Scorecard of the purchasing division (alignment checkpoint 8), which selects and manages the vendors that manufacture the shoes, clothing, and equipment that SMI sells. The products are designed to SMI specifications. Good vendors offer the following features: excellent quality, innovative styles, reliable delivery, fast development of new products, and perfect order fulfillment. Selecting and managing a high-quality stable of vendors are keys to the entire operational part of SMI’s strategy. It is particularly important that the ever changing needs of the business units be understood and translated into contracts with reliable vendors.

The purchasing department serves as the intermediary in creating alignment between the needs of the business units and the vendors. A relationship manager from purchasing is assigned to each of the business units. Her role is to be a strategic partner, managing the product sourcing needs of the business unit. Each year, as part of the annual planning and budgeting process, purchasing negotiates a service agreement with each business unit (alignment checkpoint 5). The service agreement discussion starts by examining the long-range plan, Strategy Map, and BSC of the business unit.

From this plan, the relationship manager and the business unit head establish performance measures and targets for eight parameters of purchased goods (e.g., quality, delivery, and price), as shown in Figure 1-7, and this constitutes the service agreement for the subsequent year. Each quarter, the business unit provides written customer feedback describing its assessment of the performance of the purchasing department against the eight parameters in the service agreement. This feedback provides the customer score on the purchasing division’s scorecard and is used as the agenda for a quarterly meeting between the relationship manager and the business unit head to discuss performance. The purchasing division uses an identical approach to link its numerous vendors to itself and to SMI’s business units through scorecards and service agreements (alignment checkpoint 7).

Figure 1-7 Support Unit Alignment at Sport-Man Inc

To ensure that organization alignment is managed as a continual process, SMI management has made the cascading and integration approach a permanent part of its management calendar. As shown in Figure 1-8, the annual strategic planning process begins in March with an update of SMI’s three-year forecast and strategic issues. In June, the corporate executive team meets to translate this strategic thinking into an updated corporate value proposition, Strategy Map, and BSC. In July, the business units update their strategies and cascade the corporate scorecard into updated business unit Strategy Maps and BSCs. Soon after, the cascading process is continued with service units for their strategy updates. In September, the Board of Directors reviews the corporate, business unit, and service unit strategies, with accompanying Balanced Scorecards. Simultaneously, SMI updates service agreements and scorecards with its external partners, the key manufacturing vendors.

The budgeting process begins in September and continues through year end. During this time, the finance officer and the strategy management officer review, select, and fund strategic initiatives. The service units finalize service agreements with the business units. Final approval and presentation of the budget to the board take place in December.

Finally, each individual in the organization develops a personal scorecard. The objectives and targets on those scorecards for the following year are agreed to in December. These scorecards are linked to the business unit or service unit scorecard to which the person belongs, thus ensuring complete top-to-bottom alignment.

Figure 1-9 summarizes the strategic alignment of Sport-Man, Inc., using the alignment map to describe the eight alignment checkpoints. SMI has particularly strong alignment on seven of the eight checkpoints. Only the customer interface (checkpoint 6) lacks a clear, defined alignment mechanism. This is not unusual in retail segments having large numbers of active or potential customers, where statistical measures of customer satisfaction or focus groups are used to monitor the customer interface. Business-to-business sectors with a relatively small number of customers—such as chemicals, electronics, and engineering services—tend to use more formal mechanisms, such as service-level agreements, to create customer alignment.

Figure 1-8 The Alignment and Governance Process at Sport-Man Inc.

Figure 1-9 Organization Alignment Map at Sport-Man Inc.

SMI has clearly defined its corporate role and uses scorecards and service agreements to align the corporate strategy with business and service unit strategies. It uses corporate, business unit, and service unit scorecards to communicate and gain approval of the strategy with its board of directors. During the subsequent year, the board monitors the success of the strategy through quarterly scorecard updates. SMI aligns personal performance plans with the strategies of their business or support units. SMI has created a tight web of alignment that focuses the energies of the entire organization and its strategic partners on achieving an ambitious, integrated strategy.

SUMMARY

Corporations must continually search for ways to make the whole more valuable than the sum of its parts. Alignment is critical if enterprises are to achieve synergies throughout their business and support units. A new measurement and management system, based on Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards, helps corporations define and capture the benefits of organizational alignment.

Before proceeding to the process for creating a corporate-level Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard to describe the enterprise value proposition, we embed our approach in an historical perspective. Chapter 2 describes how organizations have struggled for more than a century to find the ideal structures to manage their strategies. We believe that the search for the perfect structure will remain frustrating unless companies also use a third lever—their measurement and management systems—to align structure with strategy.

NOTES

Information on the Balanced Scorecard Hall of Fame can be found at http://www.bscol.com/bscol/hof.

These are the five principles documented in R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Competitive Environment (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

D. Rigby, Management Tools (Boston: Bain & Company, 2001).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

The following are among the important references on corporate strategy:

A. D. Chandler Jr., Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962); Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); and “The Functions of the HQ Unit in the Multibusiness Firm,” Strategic Management Journal (1991): 31–50.

M. E. Porter, “From Competitive Advantage to Corporate Strategy,” Harvard Business Review (April–May 1987): 43–59.

B. Wernerfelt, “A Resource-based View of the Firm,” Strategic Management Journal (1984): 171–180.

M. Goold, A. Campbell, and M. Alexander, Corporate-Level Strategy: Creating Value in the Multibusiness Company (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994); A. Campbell, M. Goold, and M. Alexander, “Corporate Strategy: The Quest for Parenting Advantage,” Harvard Business Review (March–April 1995): 120–132.

D. J. Collis and C. A. Montgomery, “Competing on Resources: Strategy in the 1990s,” Harvard Business Review (July–August 1995): 118–128; “Creating Corporate Advantage,” Harvard Business Review (May–June 1998): 70–83; and Corporate Strategy: Resources and the Scope of the Firm (Chicago: Irwin, 1997).

C. Markides, “Corporate Strategy: The Role of the Centre,” in Handbook of Strategy and Management, 1st edition, eds. A. Pettigrew, H. Thomas, and R. Whittington (London: Sage Publications, 2001).

J. Barney, “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage,” Journal of Management (1991): 99–120.

J. Bower, “Building the Velcro Organization,” Ivey Business Journal (November–December 2003): 1–10.

K. M. Eisenhardt and S. L. Brown, “Patching: Restitching Business Portfolios in Dynamic Markets,” Harvard Business Review (May–June 1999): 72–82.

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, “The Office of Strategy Management,” Harvard Business Review (October 2005): 72–80.