CHAPTER FOUR

ALIGNING INTERNAL PROCESS AND LEARNING AND GROWTH STRATEGIES: INTEGRATED STRATEGIC THEMES

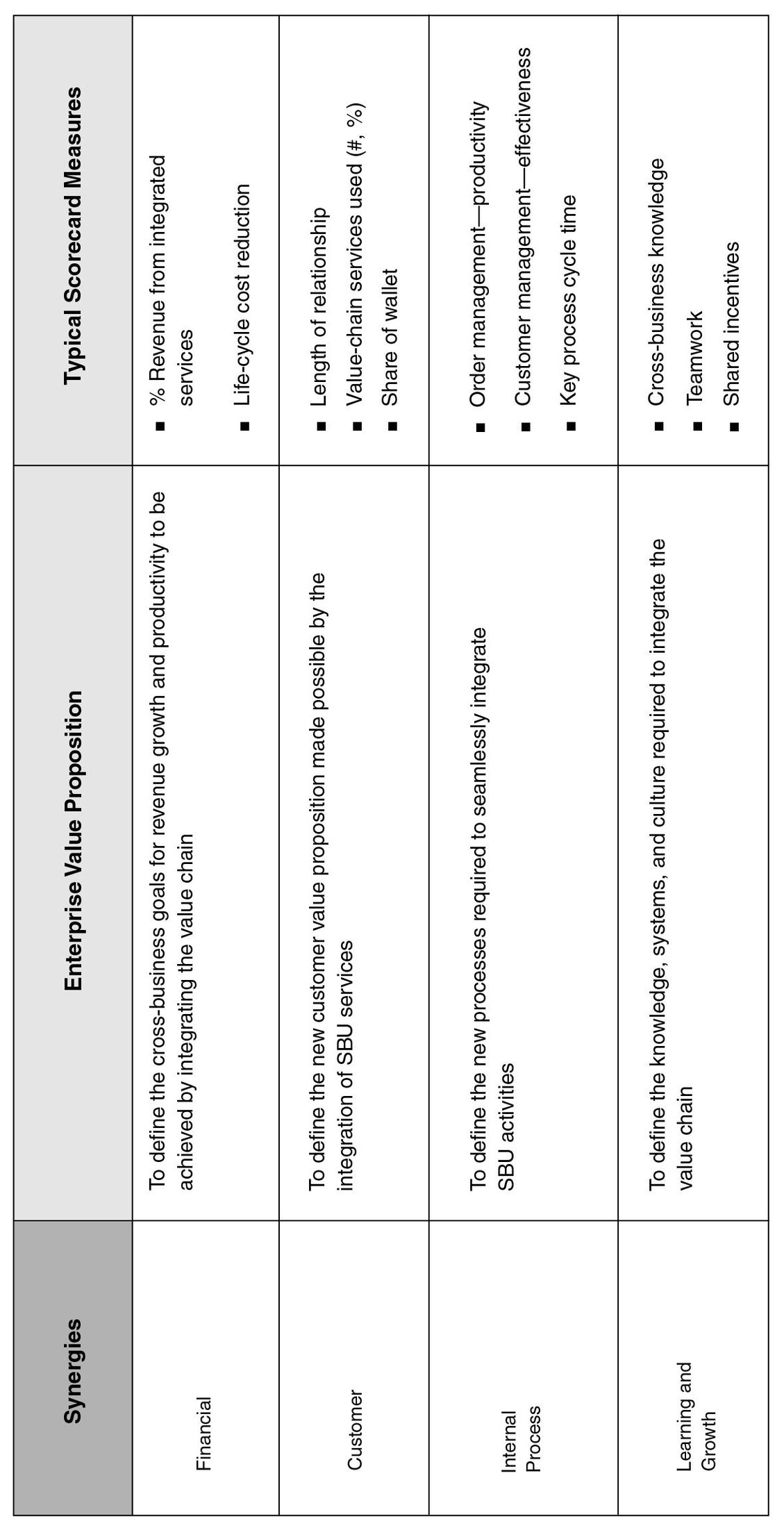

CHAPTER 3 COVERS the synergies from enterprise value propositions that align financial and customer capabilities across a collection of business units. In this chapter, we explore the opportunities organizations can exploit by aligning their internal business processes and their intangible assets to achieve enterprise-level synergies. We discuss four types of enterprise value propositions: shared processes and services, vertical integration, intangible assets, and corporate-level strategic themes.

SYNERGIES FROM SHARED PROCESSES AND SERVICES

Among the most common ways to create enterprise-derived value is by sharing common processes and services among multiple business units. The value from sharing processes and services arises in two ways. First, enterprises gain economies of scale by centralizing processes. Second, they capture the benefits of creating a centralized resource having specialized knowledge and expertise in how to operate a key process or service.

Attaining economies of scale in business processes has long been the goal and competitive advantage of large organizations. From the earliest days of the modern business era, size has created opportunity. More than a century ago, Standard Oil created a dominant advantage through the economies of its large refineries and distribution system. Today, mega-banks such as Citigroup and Bank of America create scale economies by merging the back offices of the banks and other financial institutions they acquire. The Limited, a retailer of fashion clothing for men, women, and children, consolidates the purchasing of its several divisions to create dramatic savings and benefits. It creates similar benefits by centralizing the real estate management of its retail chains. In both cases, if the processes were not centralized, the divisions would be competing with themselves in the open market for fabric and space and would lack the scale to get the best deals from overseas manufacturers or real estate developers.

The management of information technology is another function that creates opportunities for scale economies. The economics of purchasing and operating large processing centers in organizations like Citicorp (in financial services), Allstate (in insurance), and British Petroleum (BP) (in energy)—companies that spend more than a billion dollars per year on IT—create natural opportunities to reduce costs, achieve critical scale in expertise, and improve productivity. Sharing the sophisticated capabilities required for effective IT also allows organizations to improve data center security, adopt flexible standards for operating platforms, and remain current with the never-ending wave of new technologies.

Gaining economies of knowledge in business processes offers similar potential for large organizations. Although the physical management of processes may remain decentralized, the sharing of common philosophies, programs, and competencies can create significant benefits. For example, the quality movement encompasses such programs as total quality management (TQM), the Baldrige National Quality Program, the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), and, most recently, six sigma. Activity-based management stimulates process improvement and management insight, starting from the organization’s cost model. Customer management—embodied in customer value management, customer relationship management, and customer life-cycle management—is designed to focus managers and employees on operational improvements to yield better performance for customers.

These approaches to process management have helped many organizations achieve dramatic improvements in the quality, cost, and cycle times of their manufacturing and service-delivery processes. Many of the same organizations that adopt the BSC to implement their strategies inevitably need to integrate their BSC system within a management approach that often includes one or more of these management disciplines. But some organizations are confused about the relative roles of these programs and do not know how to integrate them, especially if one is already in place.

With the leadership of a corporate program, the BSC can be effectively combined with one or more of these approaches to achieve advantages beyond what any one of them could deliver on its own. The BSC imbues each with organization-wide legitimacy, giving the program a strategic context and anchoring it to the overall management system in a holistic way. The BSC’s cause-and-effect links help highlight those process improvements and initiatives that each program identifies as having the greatest impact on the organization’s strategic success.

CASE STUDY: BANK OF TOKYO-MITSUBISHI (HQA)

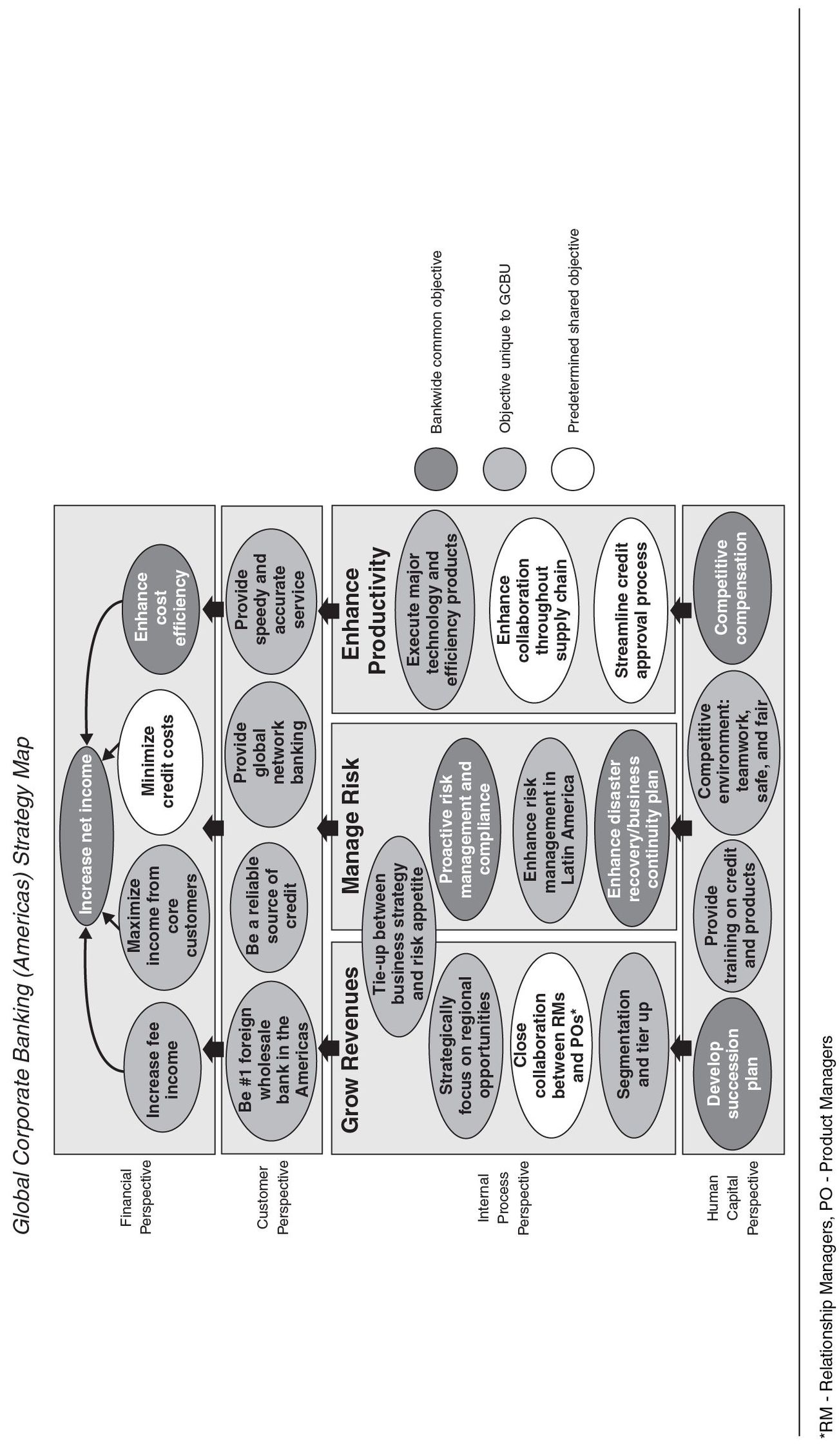

The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi (BTM) is one of the world’s largest banks. HQA, the bank’s New York–based headquarters for the Americas, manages the wholesale offerings of BTM throughout North and South America. In 2001, HQA introduced a Balanced Scorecard management program to help clarify and communicate its strategy at multiple levels, to increase accountability, to improve collaboration, and to reduce risk. We described HQA’s Strategy Map in a previous book.1 The map, reproduced here in Figure 4-1, shows the three major themes of HQA’s strategy: grow revenues, manage risk, and enhance productivity. The risk-management theme provides an outstanding example of a corporate role in the management of a common business process to create enterprise-derived value.

In the Americas region, BTM focused on the wholesale banking business, with twelve branches, eleven subsidiaries, two loan production offices, and four representative offices. Overlying this grassroots organization were four independently managed business units (global corporate banking, investment banking, treasury, and corporate center), each reporting directly to its counterpart in Tokyo. The complex organization produced many challenges to effective communication and, in particular, to effective risk management. Constant tensions existed, for example, between business promotion and credit approval. Centralized direction versus local autonomy, and expatriate versus local personnel, introduced other challenges to clear accountability.

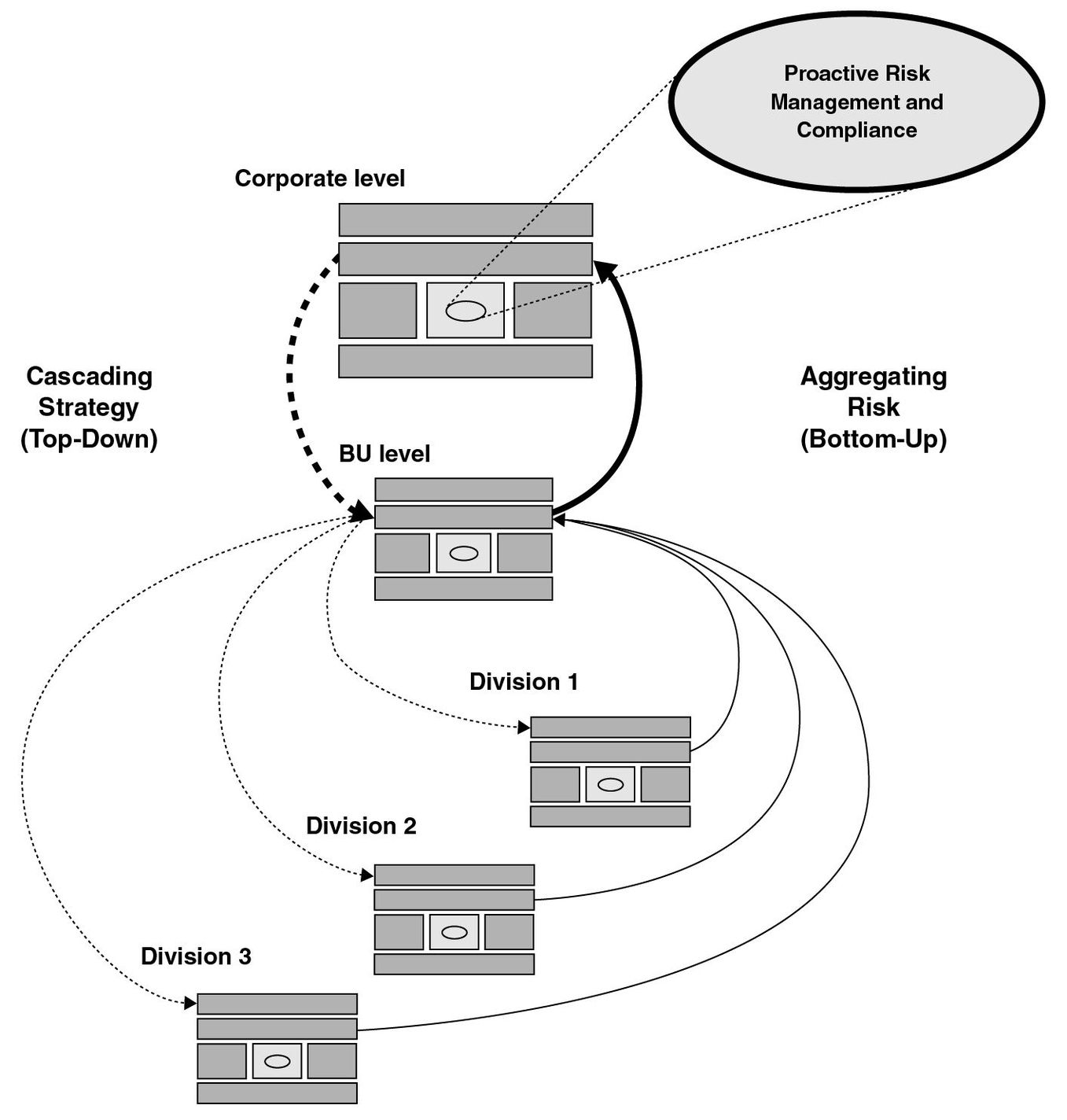

The Strategy Map framework required BTM to articulate the strategy for all organization levels from the top down. This made it easier to identify the risks associated with implementing the strategy. COSO-based risk and control self-assessment (CSA), a methodology based on the framework developed by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission, was introduced on a bankwide basis to proactively manage risks derived from strategy execution. This process, shown on the Strategy Map as “proactive risk management and compliance,” was adopted as a common bankwide objective. As shown in Figure 4-2, CSA was conducted at the lowest level of the organization. The self-assessment was based on the premise that a business is more aware of its own risks than are external parties who might perform risk audits. The CSA results were aggregated from the bottom up into two enterprise-level Balanced Scorecard measures:

- Share of issues identified by business lines (target = 50 percent). This measure highlighted, out of all the issues identified by other parties (including internal and external auditors and regulators), the percentage of the risk issues identified by the COSO self-assessment. This measure had the immediate effect of making the business lines proactively identify risks they had previously ignored or not reacted to.

- Share of issues closed during the period (target = 100 percent). The review of this measure on a monthly basis forced quicker resolution of risk issues.

Figure 4-1 Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubichi

Source : R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strtegy Maps : Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston : Harvard Business School Press, 2004), Figure 1-4.

Figure 4-2 Cascading and Managing the Risk Management Process at BTM/HQA

Source: BSCol Conference, December 11–13, 2002, Cambridge, MA, Bank of Tokyo.

By cascading the Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard from the corporate office to the business units, HQA defined an element in its enterprise value proposition: develop a common methodology for the risk-management process, linked to measures on the Balanced Scorecard, to significantly reduce business risk and secure shareholder value.

SYNERGIES FROM VALUE-CHAIN INTEGRATION

Virtually every organization is part of a broader competitive (or cooperative) environment in which customers combine the products or services of one business with those of another service provider to achieve some higher-level value proposition. For example, when buyers purchase new automobiles, usually they must also secure financing. The automobile manufacturer can elect simply to sell cars and let customers secure their own loans, or it can set up a new line of business to provide the financing. Customers must also have the automobile serviced and repaired. Again, the manufacturer can elect to let customers find their own service shops, or it can set up a new line of business that provides factory-trained mechanics to service its cars.

Both of these businesses—financing and service—create an opportunity for the manufacturer to expand the customer relationship, to increase its share of customers’ automobile-related spending, and to increase the likelihood that customers will purchase their next new vehicles from the manufacturer. The manufacturer can offer an attractive customer value proposition, one-stop shopping, by adding these new businesses.

Many industries present similar opportunities for enterprises to expand their scope into related areas in the customer value chain. For example, IBM, originally a product organization focused on computer hardware and software, expanded into the front end of the customer value chain by creating a consulting services division. This entity designs solutions for customers—solutions that, in turn, include the company’s products. IBM added another line of business on the back end of the customer value chain: an outsourcing business that takes responsibility for operating and maintaining customers’ computer-based systems.

Brown & Root Engineering Services created a new customer value proposition by combining the services of six stand-alone profit centers (engineering, procurement, construction, installation, operations support, and supply) into one integrated service. It offered customers one-stop shopping as well as a new level of operating efficiency that created dramatic cost reductions for customers.

An active headquarters role is essential to the success of such value-chain integration. Each profit center in the examples we’ve cited would have been happy to stay focused on its current market, customers, and services. But the new strategies called for separate profit centers to integrate their activities. For example, the automobile manufacturer had to modify its selling process to encourage cross-selling the financing and service businesses at the time of purchase. IBM had to create an account management process that provided a balanced presentation of its full range of services. And the Brown & Root businesses had to learn how to go to market as teams instead of separate companies. In each case, top-down corporate priorities required the SBUs to expand their scope of activities to accommodate the corporate strategy.

Figure 4-3 shows a generic corporate value proposition for a value-chain integration strategy, along with a typical scorecard. The financial objectives focus on the desired outcomes of the cross-business dimension of the strategy. Each SBU might be given the target to create new revenue by cross-selling other units’ services or selling integrated services. Similarly, it would be asked to create cost reductions resulting from cross-business activity. For example, the automobile manufacturer might look to the service company working with the dealer sales representative to help trigger a new purchase.

The cost of customer retention is a fraction of the cost of new customer acquisition. The customer perspective of the corporate scorecard describes the benefits, such as one-stop shopping and cost reductions, that the new integrated strategy creates for the customer. These benefits could be measured by the expanded breadth of the relationship, the length of the relationship, the share of customer spending, the number of services used, and reduced cost from shared or integrated services.

The internal perspective focuses on the new business processes that are needed to support the cross-business strategy. These might include order processing, which crosses business lines, integrated account management, cross-selling, marketing, and development of new services.

The learning and growth perspective focuses on the new behaviors and competencies that the cross-business strategy necessitates. Typical issues here are the need to increase cross-business awareness, product-line knowledge, teamwork, and shared incentives.

Figure 4-3 Strategic Architecture: Value-Chain Integration

The enterprise value proposition and scorecard shown in Figure 4-3 defines the specific cross-business objectives that the value-chain integration strategy requires. These corporate objectives are then cascaded to the SBUs, which then internalize the corporate objectives in their own strategies.

CASE STUDY: MARRIOTT VACATION CLUB (MVCI)

The Marriott name is synonymous with quality hotels and resorts. In addition to its flagship Marriott properties, the parent corporation includes such brands as Renaissance, Courtyard, Fairfield Inn, and Ritz-Carlton. Its frequent traveler program, Marriott Rewards, is the largest in the industry.

In 1984, Marriott entered the time-share business with the acquisition of American Resorts Group. A time-share is the purchase of an interval of time, typically one week, of product use. The approach appeals to individuals and families seeking the pleasures of a second home without the hassles. What was a fledgling industry in 1984 has expanded with unabated double-digit growth over the past twenty years. Today, Marriott Vacation Clubs consists of four brands: MVC International (MVCI), Horizons, Grand Residence Club, and The Ritz Carlton Club. Each brand addresses a different market segment. In 2003, revenues were approximately $1.2 billion and three to five new resorts were being added each year to help sustain the company’s double-digit growth.

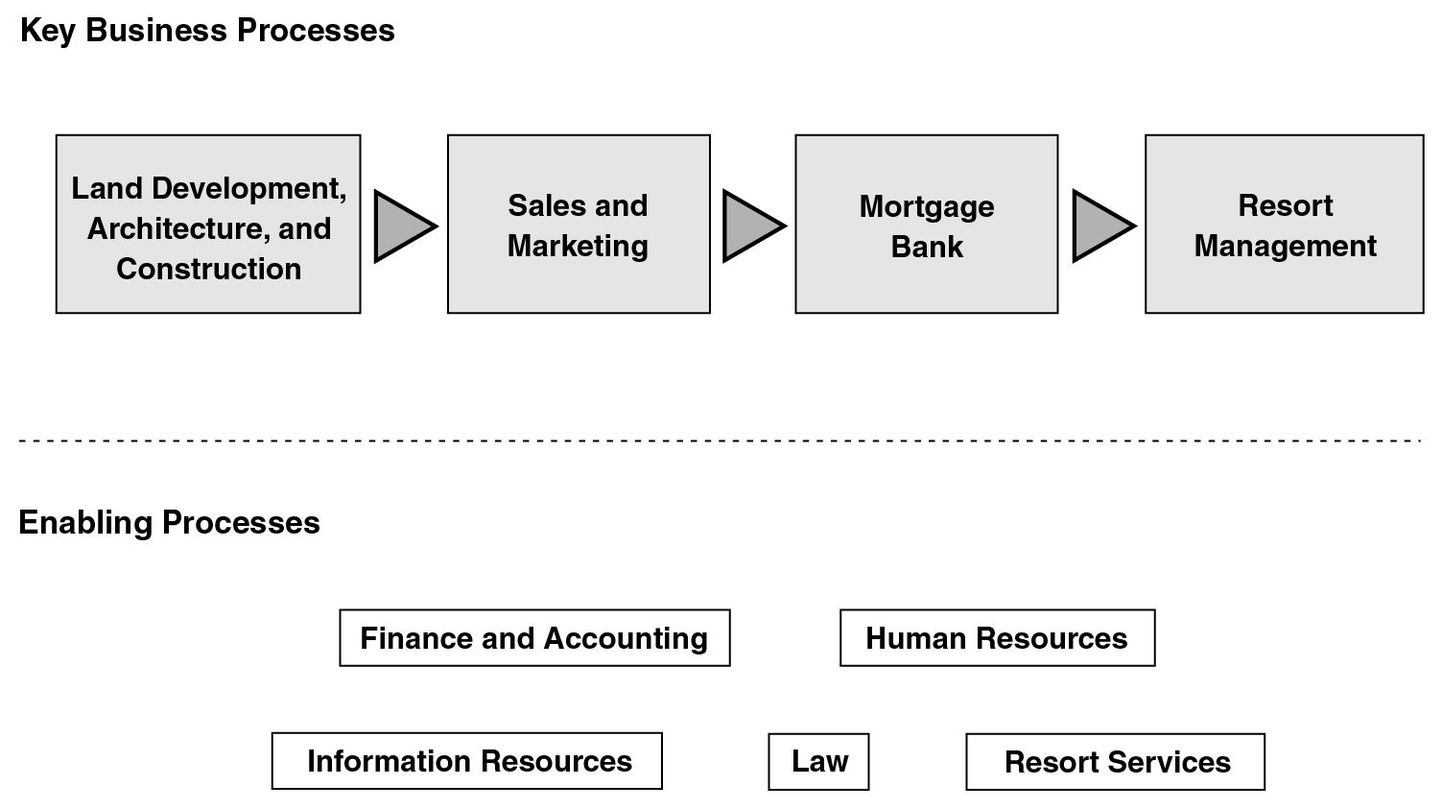

The dramatic success of MVCI was not without its challenges. The core economic model consisted of four very different businesses, each occupying an adjacent link in the industry value chain, as shown in Figure 4-4. The land development, architecture, and construction group selected locations, acquired permits and property, and designed and built resorts. The sales and marketing group sold the resort shares to end customers. The mortgage bank group supported the sales process by providing customer financing. The resort management group operated the completed resort and had the ultimate responsibility for customer service.

Although the interdependency of these four groups was obvious, their cultures and competencies could not have been more disparate. Over time, the work of these four groups evolved into silos; each group performed its own activities, with limited interaction among others. For example, if the development team ran into problems or delays, it kept these problems to itself. In the meantime, the sales and marketing team, assuming that the product would be available, began its marketing campaign, rounding up customers and selling the properties. The operations group, assuming that the product was soon to be available, began hiring and assembling a team of specialists from all over the world. Because the value chain was sequential, small problems escalated as they moved downstream. Clearly, MVCI was missing a major opportunity to create synergy and value by integrating its value chain.

Figure 4-4 The Industry Value Chain for Marriott Vacation Club International (MVCI)

Roy Barnes, a twenty-year veteran of the hospitality business, was assigned by MVCI to address this problem. His title, senior VP of strategy management and customer strategy, described his agenda: to help evolve MVCI from an entrepreneurial to a strategically managed mind-set. Barnes’s specific objective was to restructure the company, jettisoning its four siloed departments and creating a set of integrated business processes tied to the enterprise strategy. He chose the Balanced Scorecard as his framework to support this evolution.

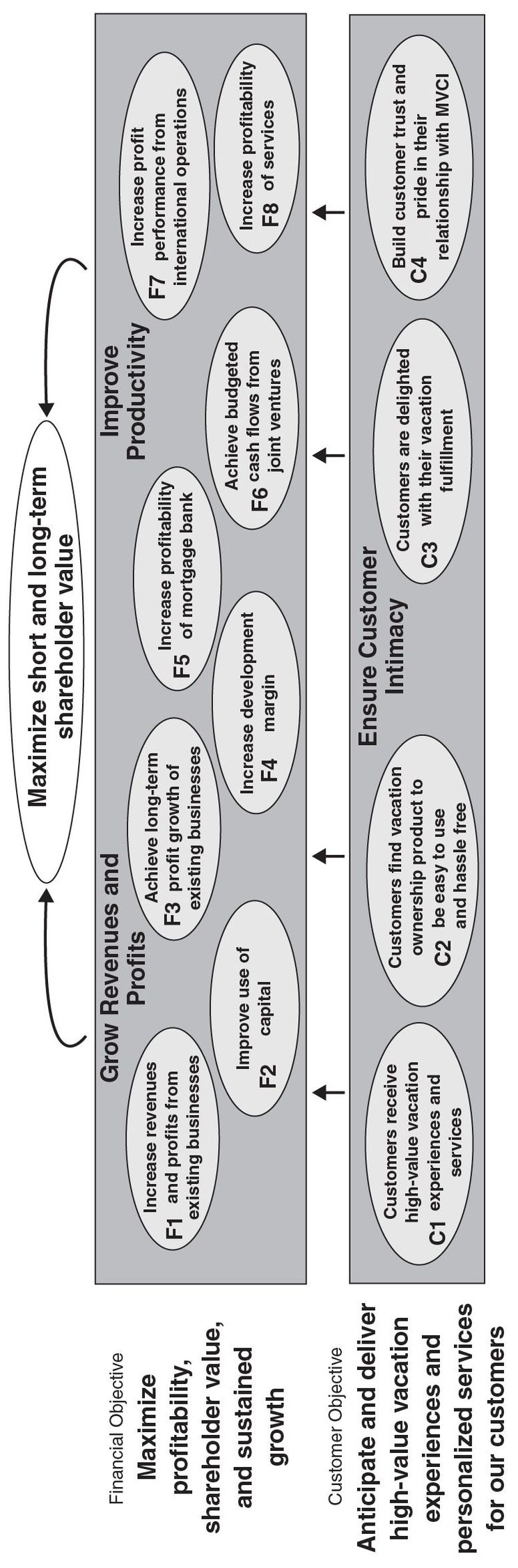

Figure 4-5 shows MVCI’s enterprise-level Strategy Map, which describes its strategy in an integrated and holistic manner. The map reflects the shift in mind-set of viewing the business as a whole instead of as a set of stand-alone, siloed functions. The corporate map defined the goal for integrated team behavior at the lower levels of the organization.

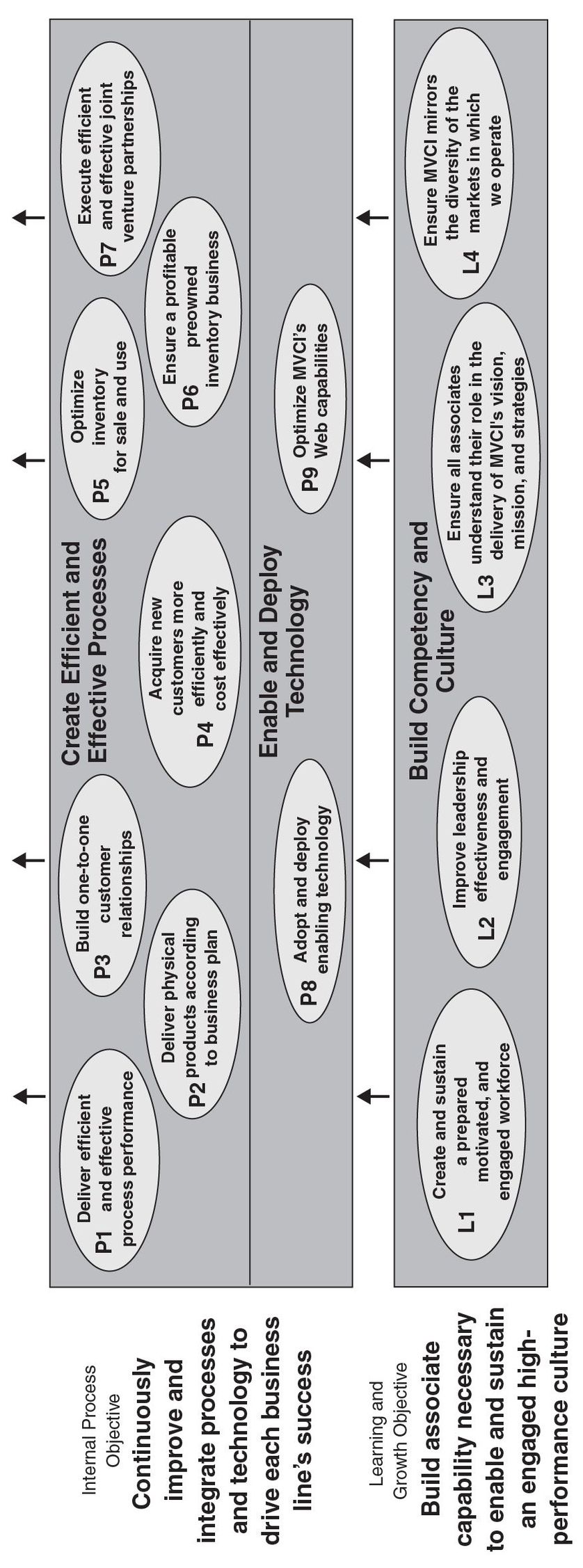

Figure 4-6 shows how the enterprise Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, once completed, were then cascaded through the four levels of the organization: from the MVCI enterprise level to the lines of business, from the LOBs to the four value-chain departments (referred to as “key business processes”), from the departments to the regions, and ultimately, from the regions to each specific resort property. Each level would align its own strategy with the higher-level one that had been cascaded to it.

Although the Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards gave Barnes the tools he needed, he still needed an extended implementation process to bring about the desired change in behavior. His change management approach consisted of five steps:

- Sell the BSC concept. Meet with business leaders from all organization levels to personally sell the new strategy and the Balanced Scorecard framework for managing it.

- Link the BSC to all other governance. Integrate the BSC into the annual cycle of strategy development, planning, budgeting, goal setting, performance reviews, and adjustment.

- Communicate the BSC strategy. Identify the target audiences. Determine appropriate messages and channels for delivery. Communicate each message seven times in seven different ways.

- Link the BSC to compensation. Tie personal incentives to the Balanced Scorecard.

- Maintain focus on the BSC. Use the BSC to monitor performance and manage the corporate agenda, thereby ensuring that the business strategy gets consistent executive visibility.

It took more than a year for MVCI to internalize the new way of managing, but the benefits from the effort were substantial. Now, each group understands the key success drivers of the group in front of it to help monitor the status of activities on which it is dependent. As a result, when the development team runs into trouble, the other groups are aware of it and act accordingly. In just one example of better coordination along the value chain, MVCI documented savings in the millions of dollars. The corporate strategy of value-chain integration was creating major synergies.

SYNERGIES FROM LEVERAGING INTANGIBLE ASSETS

Any enterprise, no matter how diversified, can create enterprise-derived value by proactively managing its leadership and human capital development. In the knowledge-based global economy, intangible assets like human capital account for nearly 80 percent of an organization’s value. Converting intangible assets to tangible results represents a new way of thinking for most organizations. Those who master this process, generally emanating from the HR organization, can create substantial competitive advantage.

Figure 4-5 MVCl’s Entreprise Strategy Map

Source: BSCol Conference, Chicago, May 11-13, 2004, Roy Barnes, MVCI.

Figure 4-6 Cascading the Entreprise Scorecard at MVCI

Source: BCSol Conference, Chicago , May 11-13, 2004, Roy Barnes MVCI.

Because every organization has workers and leaders who require development, and a climate that requires shaping, the enterprise value proposition can be to offer an effective process for developing these human capital assets. Such a process will transcend the specifics of various SBUs; the specific competencies, for example, will be different, but the process for developing them and aligning them will be the same. The corporate headquarters can mobilize three processes for developing human and organization capital across its portfolio of SBUs: (1) leadership and organization development, (2) human capital development, and (3) knowledge sharing.

Leadership and Organization Development

Modern human resource organizations are expected to guide the development of leaders and to help shape the organization’s culture. Although it is difficult to quantify, good leadership and a supportive culture are essential enablers of the successful execution of strategy. The primary objective in developing these assets is to ensure their alignment with the enterprise strategy. Leaders must understand the strategy toward which they are mobilizing their organization, and they must create the values that support this strategy. The enterprise value proposition here is to ensure the alignment of leadership and culture with the strategy.

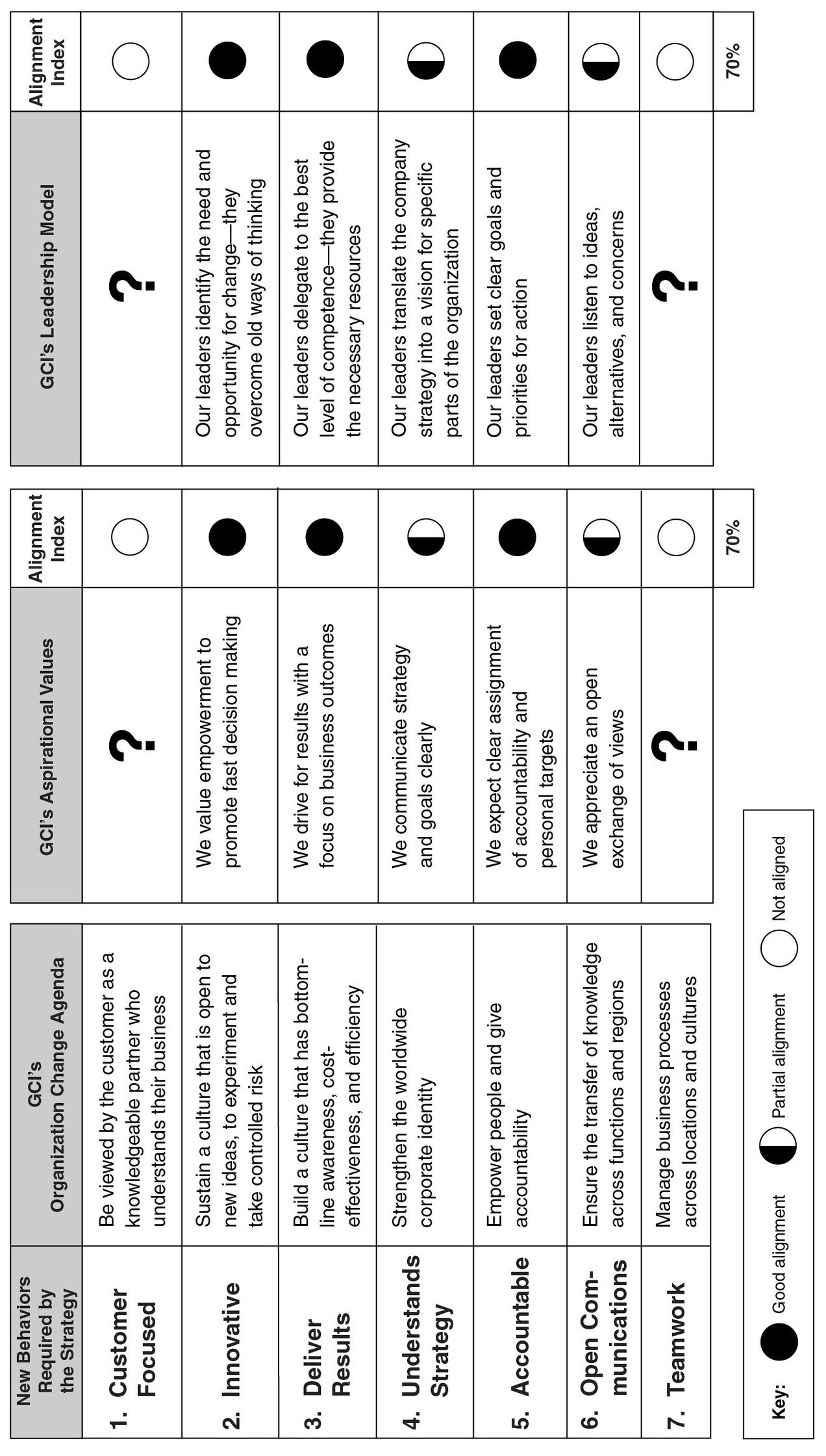

As an example of a company that was initially failing to exploit an enterprise value proposition for leadership and human capital development, consider the audit conducted by the corporate HR organization at one of the strategic business units of Global Chemical, Inc. (see Figure 4-7). The point of reference for this evaluation was the organization’s change agenda, a set of seven behaviors that the SBU’s new strategy required.2 The center panel in the figure shows the set of cultural values that the SBU was promoting in its staff-development programs. Although the SBU’s strategy required a shift from product-dominated approaches to a consultative, customer solutions strategy, no mention of customer focus was found in its “aspirational values.”

Similarly, the SBU’s strategy called for the development of regional centers of excellence. Although this specialization created significant benefits, it called for high levels of teamwork around the globe. The aspirational values defined by the HR organization of the SBU were silent on the teamwork issue. The measure of the alignment of the organization’s aspired culture with its strategic change agenda was only 70 percent.

Figure 4-7 Aligning Leadership and Culture with Strategy at Global Chemical, Inc

The rightmost panel in Figure 4-7 shows the leadership model being used by the SBU to develop its cadre of leaders. Again, the model developed by the HR organization in the SBU was silent on the subjects of customer focus and teamwork. The gap in the leadership and organization development programs revealed by the audit resulted in several major revisions to the SBU program. The corporate initiative thus improved the SBU’s ability to gain strategic benefits from these important intangible assets.

Human Capital Development

Corporations can create enterprise-derived value by improving the development of human capital throughout their business units. Even highly diversified companies operating in many different industries can create value by operating an efficient labor market among their operating companies.

Consider the example of business groups such as India’s Tata Group. The educational systems in developing nations generally do an inadequate job of preparing most students with the fundamental skills required for successful employment. Large conglomerates in these countries can afford to invest in their own education and training programs for entry-level employees and then capture the benefits as their employees pursue lifetime careers with the company. In countries having more developed and more mobile labor markets, the individual receiving the company training would capture most of the benefits through higher wages and the threat of joining a competitor if salary increases were not forthcoming. The corporate Balanced Scorecard of a holding company that actively managed its internal labor market would include objectives relating to rotation of key staff throughout its companies and promotion of executives from one company to another.

Large diversified companies, such as General Electric, also offer exceptional career development opportunities for employees in their various businesses. Steve Kerr, former chief learning officer at General Electric, described how the product lines and geographic diversity of GE allow it to provide unique opportunities for young, promising managers at “popcorn stands” around the world—small businesses whose success or failure would not affect any of the first three digits of GE’s annual operating income. 3 GE uses the information it gathers about managers’ performance at these small businesses to assess which managers it should promote, invest in further, and give greater responsibility to in a different GE company that operates in a different part of the world. At the culmination of twenty or so years of such experiences, GE has produced a cadre of proven leaders capable of major responsibility at its large product and geographic divisions.

Corporate learning and growth objectives relate to recruiting the best talent into the operating companies, operating an outstanding corporate university for internal training and education, providing varied career development opportunities for emerging leaders in the corporation, and sharing best-practice knowledge about similar processes throughout the operating companies.

The greatest payoff comes from an increased focus on strategic competencies. Many organizations are creating the specialized role of chief learning officer (CLO) to accomplish this objective. Strategic competencies are the skills and knowledge the workforce must have to support the strategy. Investing in employee learning and development constitutes the true starting point for any long-term, sustainable change. For knowledge-based organizations, the ability to improve business processes that support a customer value proposition depends on employees’ ability and willingness to change their behavior and apply their knowledge to the strategy. Therefore, organizations that want to ensure the success of their strategies need to understand the required human competencies. They need to assess the current level of strategic competencies and develop programs that will fill any gaps in the organization’s competency profile.

Although competency development programs are not a new idea, tying such programs to the strategy—something that is made possible through the use of the Balanced Scorecard—is new. In recent years, organizations have begun to define strategic job families, or competency “clusters” associated with specific strategic processes. By identifying the relevant strategic job families, organizations can ensure that they develop the right competencies—those that will accelerate strategic results. The importance of understanding and managing strategic job families has been underscored by John Bronson, senior vice president of human resources at San Francisco–based Williams-Sonoma, who estimated that people in only five out of all the company’s many job families determine 80 percent of his company’s strategic performance.4 (At the average midsize to large corporation, only about 10 percent of all job families are strategic.)

Several approaches can be used to close the gap in strategic competencies: recruiting, training, career planning, and outsourcing. The right mix of these approaches will be determined by the strategy’s timetable as well as by the flexibility afforded by the available talent pool.

Kinnarps, a Swedish furniture manufacturer, used its Balanced Scorecard to align the competency development for every employee to strategy execution. The company’s internal training group, Kinnarps Academy, maps every employee’s competency and compares the employee’s competency profile with the actual competencies required for the position as specified by the strategy. The academy then develops customized competency development programs for employees to acquire the skills needed to meet the company’s strategic objectives. The head of Kinnarps Academy says that the BSC has helped the academy be more proactive and goal oriented in its competency development.5 Kinnarps uses an IT program to track competency development investments; the program maps skills to strategy and shows how much is financially lost or gained by an employee’s competency level. The importance of closing the competency gap can thus be understood in terms of its financial impact.

Knowledge Sharing

All enterprises can benefit from knowledge sharing throughout the organization. Even highly diverse business units, having different targeted customers and diverse value propositions, still conduct many similar or identical processes, such as payroll, monthly financial reporting, recruiting, annual employee performance reviews, purchasing, vendor selection and payment, shipping, receiving, and scheduling.

By sharing information about common processes, the enterprise has more opportunity to identify a best practice that can be implemented quickly across all business units. This best-practice knowledge capture and sharing will occur sooner and at lower cost than if independent companies had to contract among themselves for periodic benchmarking studies. For knowledge sharing , the larger and more diverse the corporation, the greater the chance that a process innovation will occur that can be leveraged into benefits throughout the corporate business units.

In many cases, responsibility for knowledge capture and transfer has been assigned to a new organization position, the chief knowledge officer (CKO). Although the field of best-practice management is mature, ways to link specific best practices to strategic outcomes is less well understood. Traditional approaches to leveraging best practices are typically independent of strategy. We are now seeing many organizations use their BSC reporting capabilities to identify high-performing teams, departments, or units based on their ability to deliver strategic results. This makes it possible to document the reasons for high performance and to disseminate this information broadly throughout the organization, thus educating and training others about how they can improve their performance.

Crown Castle International’s (CCI) knowledge management system, CCI-Link, is a comprehensive database and library of the company’s best practices. This knowledge management tool centralizes and shares performance information and best-practice knowledge throughout this global and highly decentralized company.

CCI uses the BSC to benchmark each of its forty district offices on strategic performance measures. Benchmarking helps executives discover which strategic processes and practices are performed best within the firm and helps them train people in other areas of the organization on these processes and practices so that they can meet the highest performance levels. A focus on internal best practices allows Crown Castle to incorporate the lessons learned and helps integrate the strategy, scorecard, process improvement, and training activities throughout the organization.

Crown Castle’s knowledge management practice has contributed immensely to alignment and operational efficiencies, especially amid a period of job cuts. CCI-Link’s core architecture is common across diverse geographies. Countries have common, traditional functions listed, such as finance, assets, and human capital, but the content is largely local. A detailed analysis helps differentiate between geographic areas so that managers can understand the true basis for performance differences.

In a Nutshell

Building the human capital and organization capital of the enterprise is everyone’s job; the HR organization is expected to take the leadership role. Our experience indicates that if these processes are linked to strategy, the value of the enterprise’s human capital increases dramatically. We have described elsewhere how creating alignment and measuring strategic readiness enable HR executives to manage these processes.6 Strategy Maps provide another tool for aligning human capital with the strategy.

Clearly, the science of managing human capital is emerging. New management processes are needed to apply this science. Although a promising 43 percent of HR organizations appoint a representative to help business units manage their HR relationship, according to a survey by Balanced Scorecard Collaborative and the Society for Human Resource Management, only 19 percent actually integrate their strategic plans with those of the enterprise.7 Developing these new processes will increase the value of an organization’s intangible assets.

CASE STUDY: IBM LEARNING

The quality of its people, its leadership, and its culture has long been a differentiator of IBM and fundamental to its success. Through the decades of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, IBM’s people created the most successful company in business history. They combined leadership in the evolution of new technologies with a powerful marketing and sales process to generate strong customer loyalty. IBM invested heavily in the development of its people’s competencies and leadership—the foundations of its success.

This success came to an abrupt end in the 1990s. Although IBM’s laboratories continued to develop the technologies of the future, the enterprise organization could not change its traditional business model. IBM’s strong culture, which had been one of its major assets, turned into a liability. It became a barrier to change in an industry where change was a constant. IBM lost more than $16 billion in the early part of the decade. Many people felt that the company should be broken into pieces and sold.

Lou Gerstner, who had been hired as CEO from outside the company, came to the opposite conclusion. He believed that customers wanted a company that could integrate the diverse spectrum of information technologies and that IBM was best positioned to be that integrator. History has shown the brilliance of that insight. By the year 2000, IBM had returned to its position of industry leader. Under the leadership of Sam Palmisano, the new IBM continues to evolve. The role of leadership, culture, and staff learning remains central to the IBM strategy.

In May 2001, Ted Hoff joined IBM as vice president of learning to help develop these intangible assets. As IBM’s chief learning officer, Hoff was responsible for learning initiatives across the company, developing management training, functional guidance for employees, technical and sales training, and technology-enabled learning. He became a member of IBM’s senior leadership group and the global HR leadership team.

Hoff found, upon his arrival, that IBM was still investing heavily in learning; more than $1 billion per year was being spent. In spite of this significant investment, however, line managers did not know how much they were spending nor what they were getting in return. Learning was an “HR issue.” No strategic planning process existed to integrate learning with the business. Learning was not positioned to be a key driver of business and organization success. Hoff’s corporate mandate was to change this.

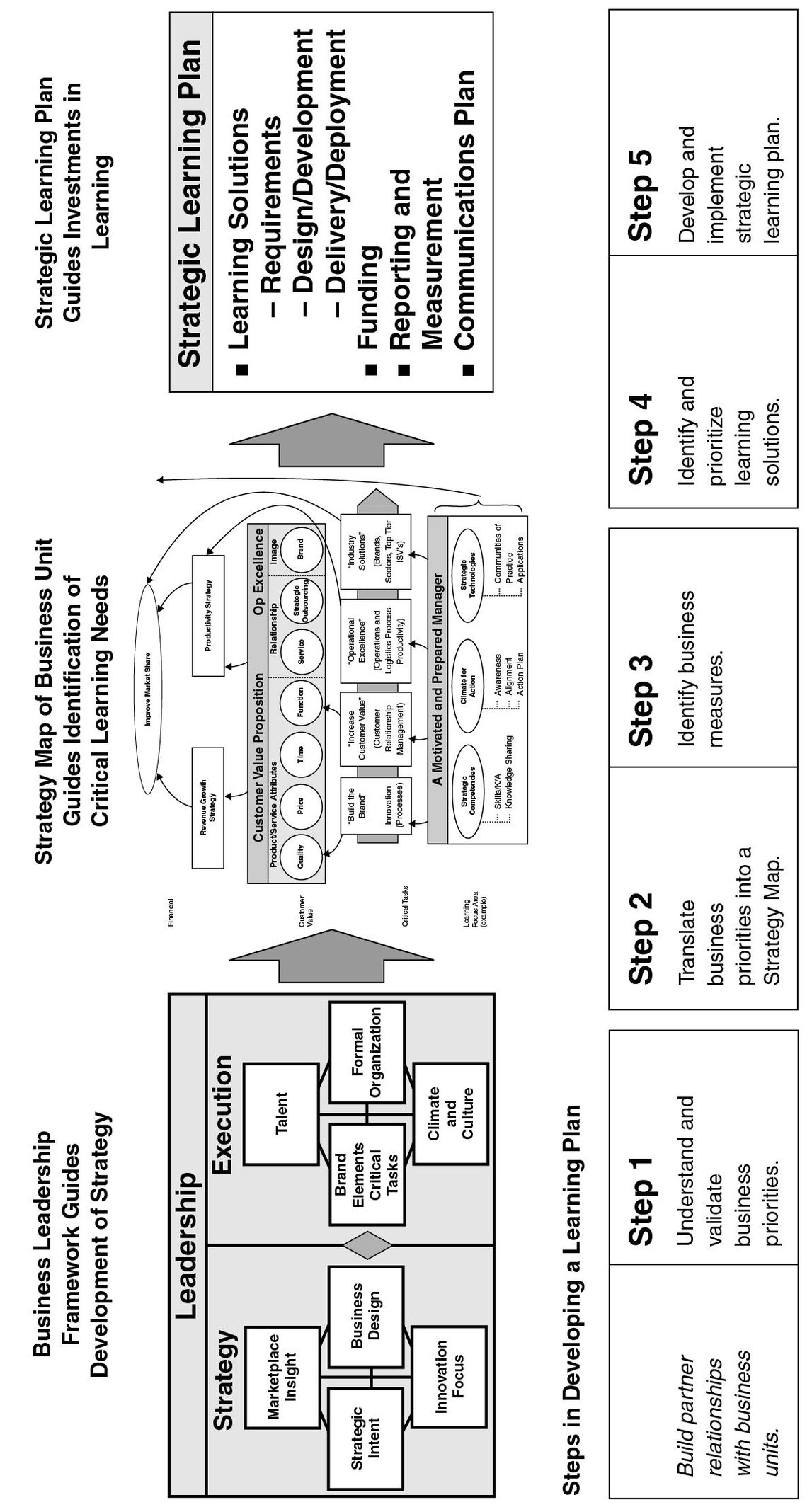

Figure 4-8 summarizes the approach IBM used to align its $1 billion learning investment with the company’s strategy. As shown in the box on the left, IBM has a well-defined strategy formulation process and a leadership-driven approach to execution. The box on the right summarizes the investments in learning that support the strategy. Historically, however, there had been no effective way to ensure that these investments were, in fact, aligned. The Strategy Map of the business unit, shown in the center box, proved to be the missing link. The business strategy was translated into a Strategy Map, a step that enabled the learning organization to focus its investments on strategic priorities.

A five-step Strategic Learning Planning approach was developed and used in each major business unit. Before starting the process, however, a strong partnership relationship had to be built with line management. Hoff assigned a “Learning Leader” from his organization to each unit. This person’s role was to serve as the integrator by (1) understanding the BU’s strategy and (2) developing an appropriate learning strategy.

Step 1—Understand and validate business priorities. The Learning Leader was responsible for research and analysis of the BU strategy. Strategy documents, marketplace information, budgets, business plans, and the Internet, as well as direct interaction with the BU, were typical sources. The Learning Leader partnered with other support teams such as HR, Finance, and Strategy to execute its mission.

Step 2—Translate business priorities into a Strategy Map. Based on the research and interactions, the Learning Leader created a draft Strategy Map of the BU. The draft identified specific issues, objectives, and strategic themes. Through a series of executive interviews, the Leader then validated the Strategy Map. These interviews helped to identify the critical business areas on which the learning programs should be focused. A validated Strategy Map resulted.

Step 3—Identify business measures. A Balanced Scorecard of measures and targets was then derived from the Strategy Map. The Learning Leader used this process to educate the client on the link between intangible assets and tangible business results.

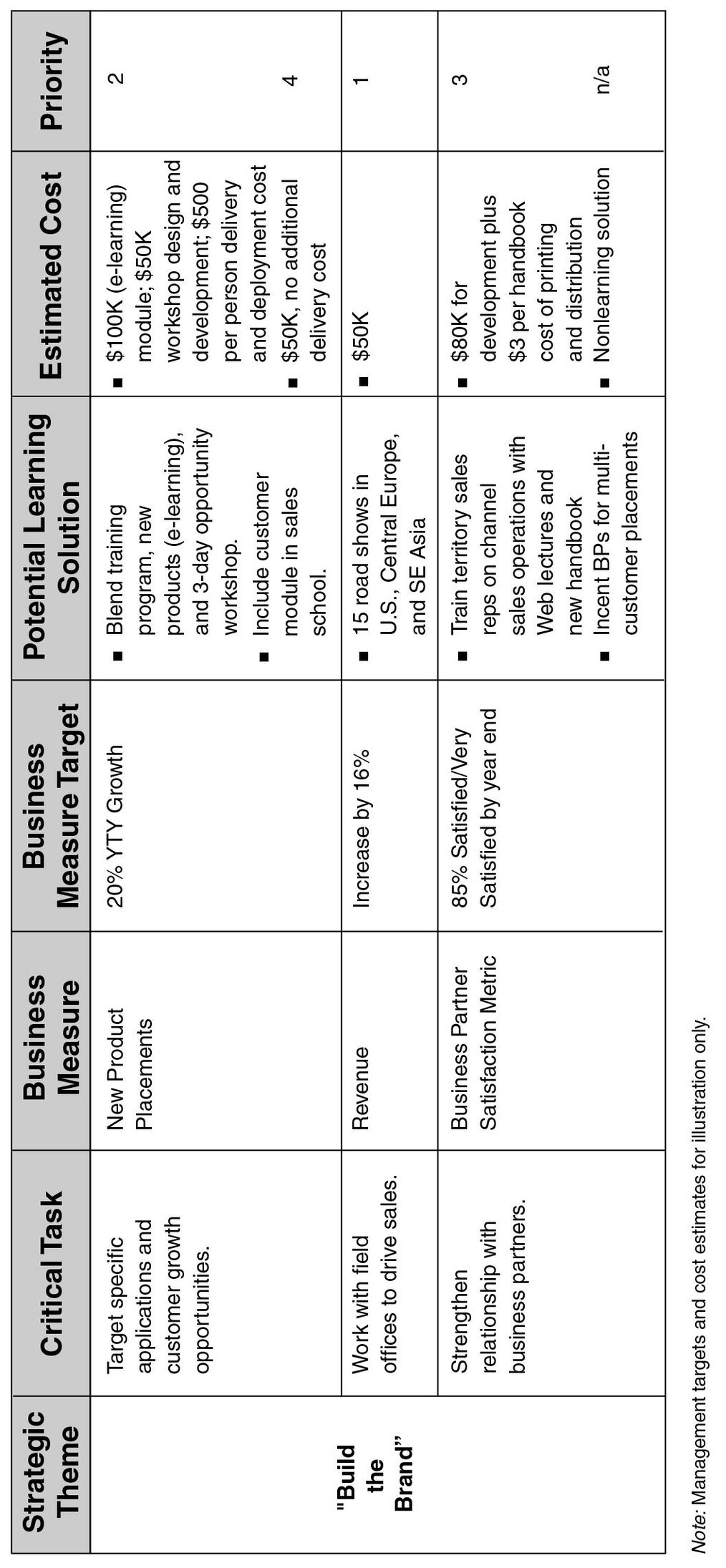

Step 4—Identify and prioritize learning solutions. The culmination of this planning process was the development of a set of learning solutions to support the strategy. Figure 4-9 illustrates the alignment of potential solutions to enable critical business imperatives. BU sponsors were identified for each program. Solutions that fell outside the learning domain (e.g., climate, incentives) were identified for subsequent discussion with HR and line management. The cost of developing and deploying each potential solution was identified. The potential investments were then ranked based on their anticipated impact on scorecard measures. This list provided the final input for construction of the BU’s support plan.

Figure 4-8 Aligning Strategic Learning With Business Units at IBM

Figure 4-9 Aligning Performance Solutions With Business Parners at IBM

Step 5—Develop and implement strategic learning plan. The business analysis and planning performed in Steps 1 through 4 were then consolidated into the final Strategic Learning Plan for the BU. Funding was gained to implement the solutions. A communication plan to support the deployment of the plan was developed and a process of measuring, reporting, and reviewing progress against the plan was developed.

Through the use of Strategy Maps and the Balanced Scorecard, learning investments at IBM now have “line of sight” alignment with business goals. The approach has made a material difference on the integration of different parts of the IBM organization. As described by Ted Hoff, “We are now at the table with the business.”8 The learning organization participates in strategic planning, budgeting, and investment/return discussions. They have access to senior executives as needed. Learning organization staffs are now accountable for results. Most importantly, IBM is converting this most intangible of assets (learning programs) into tangible business results.

INTEGRATION USING CORPORATE STRATEGIC THEMES

Large multiproduct, multiregion organizations strive to achieve competitive advantage through economies of scale and scope among their decentralized units. These companies have a difficult task because the business units must be responsive to local markets and challenges while also helping the corporation capture the scale and scope benefits that result from integrating their operations with other business units. Because the decentralized units have multiple responsibilities, it is difficult to define a sound basis for performance and accountability.

For more than a century, companies expanding into new product lines, new market segments, and new regions have employed a variety of organizational design approaches, some of which we described in Chapter 2. Among the choices are organizing by function, by product, by customer and market segment, or by geography. None of these worked perfectly, so newer forms—including organization by matrix, technology, channel, network, and virtual—have also been tried. Despite all this innovation in organization structure and form, however, the problems of coordination, alignment, and accountability remain.

Several complex organizations have used a corporate-level Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard to create alignment and integration among their diverse and dispersed units. Typically, these two documents enable the enterprise to articulate high-level strategic themes. These enterprises took their existing structure as given, feeling that tinkering by realigning authority, responsibility, and decision rights among operating units would not provide the magic they needed to achieve corporate-level synergies. Rather than continue to search for an ideal but never attainable structural solution, they articulated strategic themes in their corporate scorecard, believing that these would provide an informational solution for allowing decentralized units to seek local gains while also contributing to corporate-wide objectives.

Aligning disparate organizations through strategic themes is especially valuable for public-sector agencies and departments. The problems that the public sector is trying to solve are extremely complex and difficult: drug trafficking, illegal immigration, homelessness, poverty, welfare dependency, teenage pregnancy, environmental pollution, homeland security, crime, intelligence, structural unemployment, and many others. It would be highly unlikely that any single organizational unit, agency, or department had all the authority, resources, and knowledge to solve these problems by itself.

Also, in contrast to the private sector, realigning existing governmental agencies and departments so that they can address a particular problem is a Herculean effort, with progress typically measured in geological time. Each department or agency has its own constituency and, typically, its own band of supporters in the state or national legislature. Attempting to restructure or combine agencies to accomplish a mission more effectively runs into immediate, focused, and highly organized resistance.

Therefore, governments that want to create positive social impact must operate with their existing units, which were formed through a somewhat random, unmanaged, historical time path. Their challenge is how to mobilize diverse agencies—having different missions, different histories and cultures, and different support bases—to cooperate so that collectively they can achieve outcomes beyond what they would accomplish operating independently. Multiple agencies, often at various levels of government and in different jurisdictions, must coordinate their efforts—not a natural act for government bureaucracies—if they are to achieve positive social impact.

In this situation, the Balanced Scorecard provides an ideal mechanism to set high-level, interagency objectives that allow the multiple agencies to work together to accomplish the mission. Thus, we should expect to see public-sector scorecards developed for high-level, multiorganizational initiatives or strategic themes. The Balanced Scorecard provides the context and the process for engaging representatives from the multiple public-sector agencies in high-level discussions and cooperation.

We use three case studies to illustrate the role of corporate-level strategic themes in integrating the operations of diverse and dispersed organizational units. DuPont Engineering Polymers is a representative private-sector example, with its use of five time-sequenced strategic themes. Royal Canadian Mounted Police, a public-sector counterpart to DuPont EP, also used five strategic themes to align its international, national, provincial, and municipal operating units. The Washington State salmon recovery effort illustrates the role of building a high-level Balanced Scorecard to align agencies in different departments and governmental units to address a major public policy issue.

CASE STUDY: DUPONT ENGINEERING POLYMERS DIVISION

The Engineering Polymers (EP) division of DuPont had $2.5 billion in annual sales and employed 4,500 people in thirty operating facilities around the world. EP, like many multinational, multiproduct organizations, experienced difficulties in implementing a coherent strategy throughout its eight related global businesses and six shared-service units.

Like many matrix organizations, EP experienced confusion about roles and responsibilities. People were starting initiatives that were not coordinated across the business, and other new initiatives were generally underfunded and understaffed, so business continued as usual. During the five years before adopting the Balanced Scorecard, EP had compounded annual earnings growth of 10 percent, but this was achieved mainly by cost-cutting and productivity improvements, because revenue growth was only 2.5 percent annually. Craig Naylor, group vice president and general manager, saw how to use the Balanced Scorecard to align all employees, business units, and shared services to a common strategy that featured revenue growth. Subsequently scorecard measures would provide feedback to continually test the strategy.9

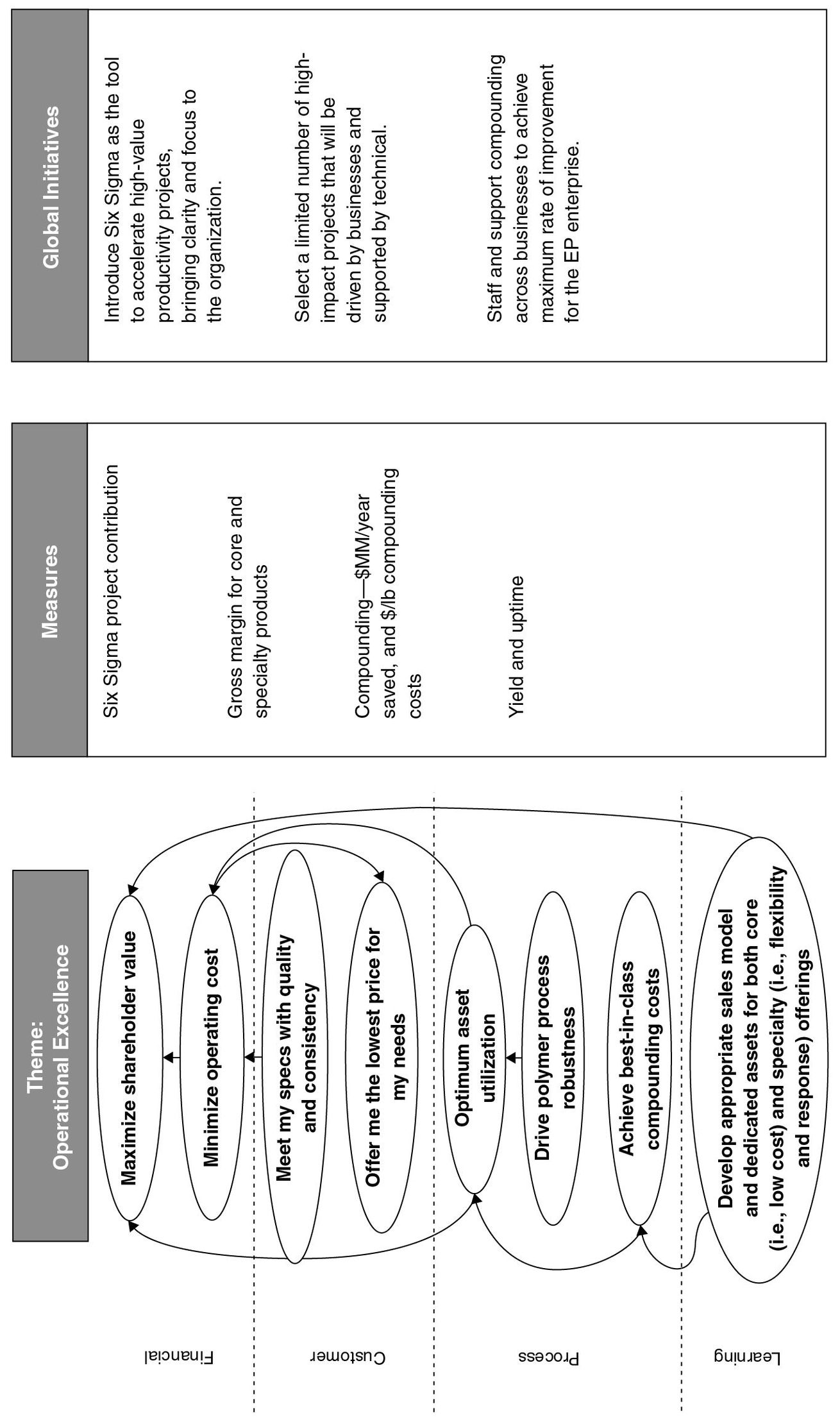

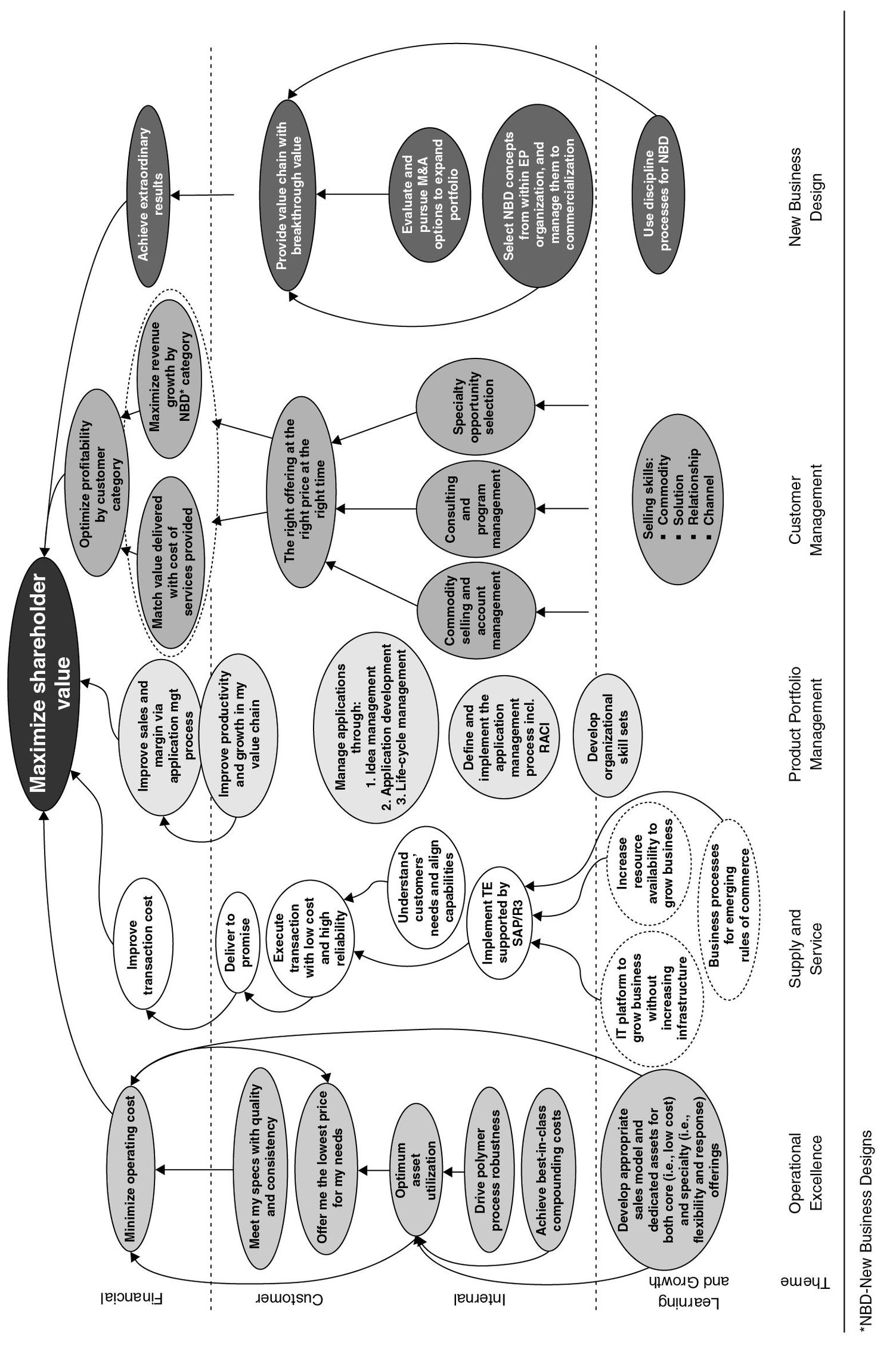

The new strategy had an overarching objective to maximize shareholder value through a combination of productivity improvements and growth opportunities. The improvements in productivity involved both continuous and step changes in process capabilities. The company expected to generate growth opportunities by offering more integrated products and services to customers. DuPont EP’s senior management team built a divisional Balanced Scorecard Strategy Map around five time-sequenced strategic themes that described how the units could align their actions to deliver the revenue growth and cost-reducing financial objectives. The five themes were as follows:

Operational excellence: Deploy process improvement tools such as six sigma and cost reduction to deliver significant productivity improvements.

Supply and service: Create differentiation for customers through logistics excellence to reduce the order-to-cash cycle.

Manage the portfolio of products and applications: Focus on products and applications having the highest margins, and introduce new products and applications.

Customer management: Bring complete solutions to targeted customers, offering a unique package of capable products, low cost, and excellence in supply.

New business design: Devise entirely new ways of reaching and servicing end-use customers.

The sequence of themes corresponded to the time frames required for successful implementation: improving operating processes and logistics would deliver near-term (nine to fifteen months) results. It would take two to three years to create portfolios of products that would provide more complete customer solutions. Realizing the benefits of developing and installing an entirely new business model with customers would take three to four years.

EP developed Strategy Maps and assigned a manager to be accountable for each of the five strategic themes. For example, Figure 4-10 shows the Strategy Map for the first theme: operational excellence. This theme stressed delivering existing products better, faster, and cheaper to customers. The theme’s measures and targets related to specific improvements in cost, quality, yield, and equipment availability. The theme’s strategic initiatives included six sigma quality programs and best-practice sharing across business units to maximize the rate of learning and improvement throughout the division. Figure 4-11 shows the complete EP Strategy Map, which is built on the five sequenced strategic themes.

Figure 4-10 DuPont EP Operational Excellence Theme: Strategy Map, Measures, and Initiatives

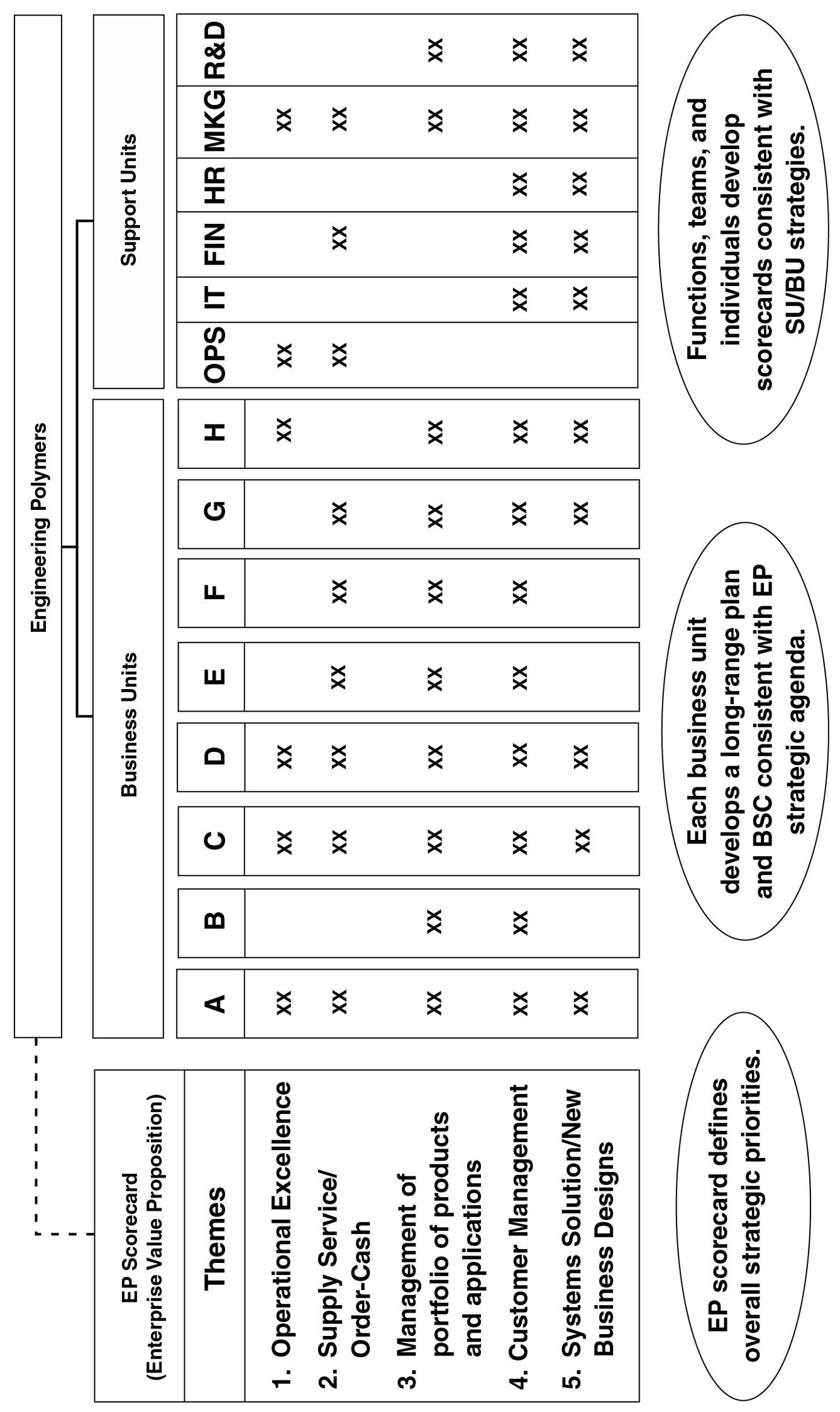

EP viewed the five themes as the DNA of its strategy, the genetic code that would be embedded in every business unit and shared-service unit. EP cascaded the high-level strategic themes by having its three major geographic regions and five product-line units build their own scorecards. These business unit scorecards highlighted how the five themes would be implemented in each region and product line as well as each unit’s unique objectives and initiatives for its local strategy.

Similarly, the global functional units—manufacturing, IT, finance, HR, marketing, and R&D—constructed their own scorecards to ensure that functional excellence would be developed and deployed to assist the global, regional, and product-line strategies. The actual content of each theme could differ in each business unit, but all businesses built their individual strategies around the five themes (see Figure 4-12). This approach made opportunities for leverage and synergy across business units far more visible than ever before.

Note that only a few business units were expected to make a contribution to all five themes. Several focused on as few as two of the themes. In constructing its individual Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, each unit reflected how it could contribute to the division-level themes and also how it needed to cooperate and integrate with other business and support units to achieve cross-unit synergies. The structure shown in Figure 4-12 enabled EP senior management to know what was unique for each business unit and shared-service unit, and which objectives required integrated solutions across several units.

EP, like most organizations, faced a classic conflict. The local businesses and their employees wanted to focus on running their businesses efficiently day-to-day. It was difficult to get sufficient attention from them to align their businesses to divisionwide strategic initiatives. To get share of mind for initiatives relating to EP’s five new strategic themes, amid all the other programs and initiatives already under way, managers forced out many local projects that were not contributing to one or more of the five themes. This made space for new initiatives and projects that would enhance the divisional strategic themes so that they became embedded in the ongoing day-to-day routines of employees.

An often fatal weakness of a matrixed organization is the endless debates that occur among business units, functional departments, and geographical regions about resource allocation. EP reported that the clarity of the five strategic themes, cutting across business units, geographical regions, and shared-service functions, forced greater clarity about priorities and provided more transparency for resource allocation. This led to more productive discussions and dialogues based on a shared understanding of the fundamental drivers of overall business performance. Individuals used the scorecard architecture and measures to gain support for agendas and projects. Enthusiasm and constructive discussions pervaded the organization because of the shared understanding of strategy.

Figure 4-11 DuPont EP Strategy Map, Five Corporate Themes

Figure 4-12 DuPont EP:Aligning Business Regions, and Support Functions with Five Strategic Themes

At DuPont Engineering Polymers, the strategic themes described a strategy that did not change even in its highly dynamic and competitive environment. Although tactics and initiatives may change bimonthly, EP’s strategic themes emphasized fundamental objectives for the organization: improve the supply chain, work better and more closely with distributors, and build new business relationships with end-use customers. These themes were not ephemeral. They sustained organizational direction and focus for years—not weeks, months, or quarters.

CASE STUDY: ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE

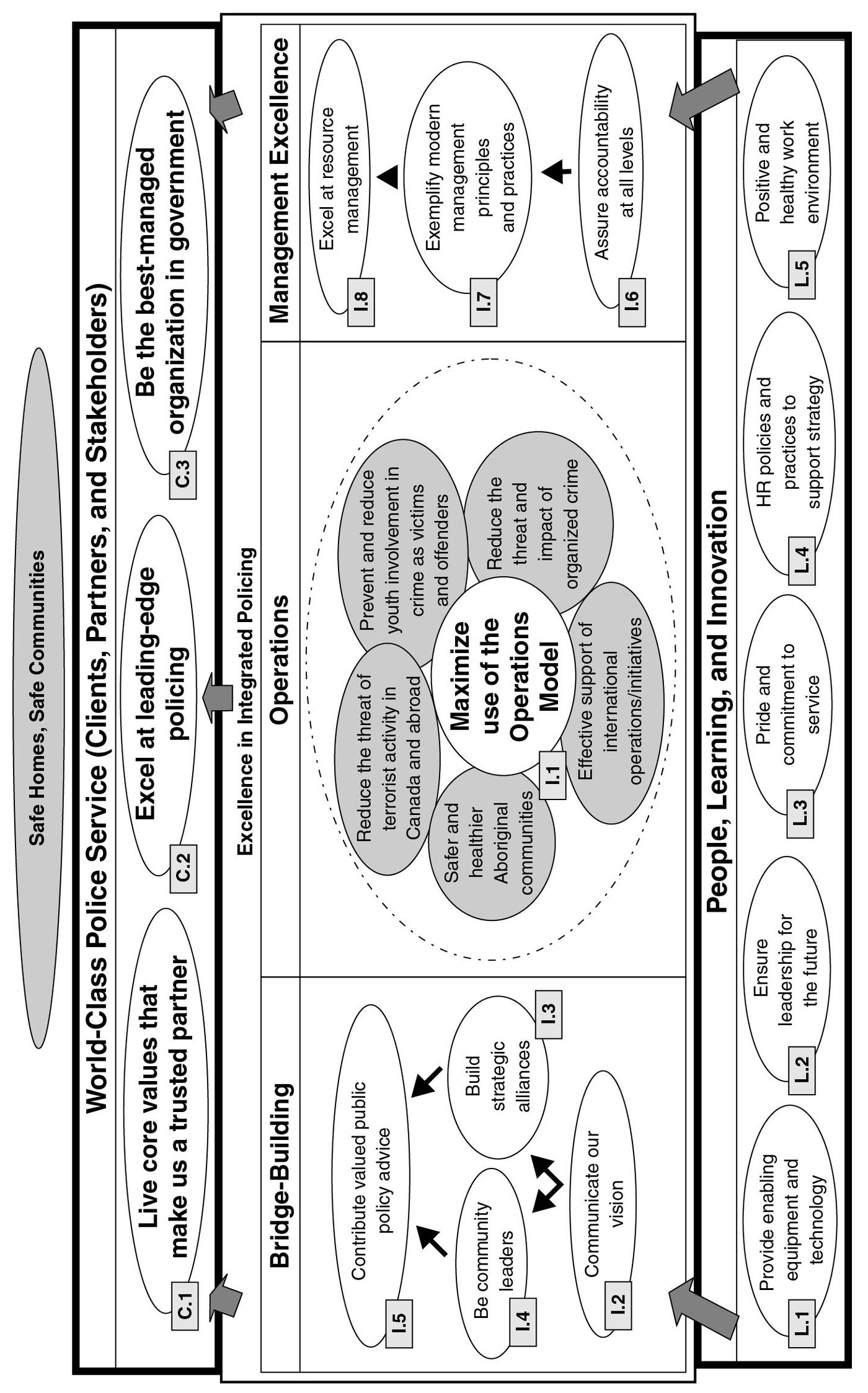

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), with twenty-three thousand employees and a C$3 billion annual budget, is Canada’s national policing service, and also provides contract policing services for Canadian provinces, territories, and municipalities. The RCMP operates at four levels—international, national, provincial/territorial (eight provinces and three territories), and local (over 200 municipalities and 190 First Nations communities). At the turn of the twenty-first century, the RCMP faced several challenges, not the least of which related to finances and resources required for a policing organization entering the new millennium. A new commissioner, Giuliano Zaccardelli, committed himself to continued management improvement at the RCMP. He had a vision that the RCMP could become a strategically focused organization of excellence. Even with his strong leadership and vision, Commissioner Zaccardelli faced the challenge of how to align all RCMP units, spread across an enormous land mass, to corporate-level priorities.

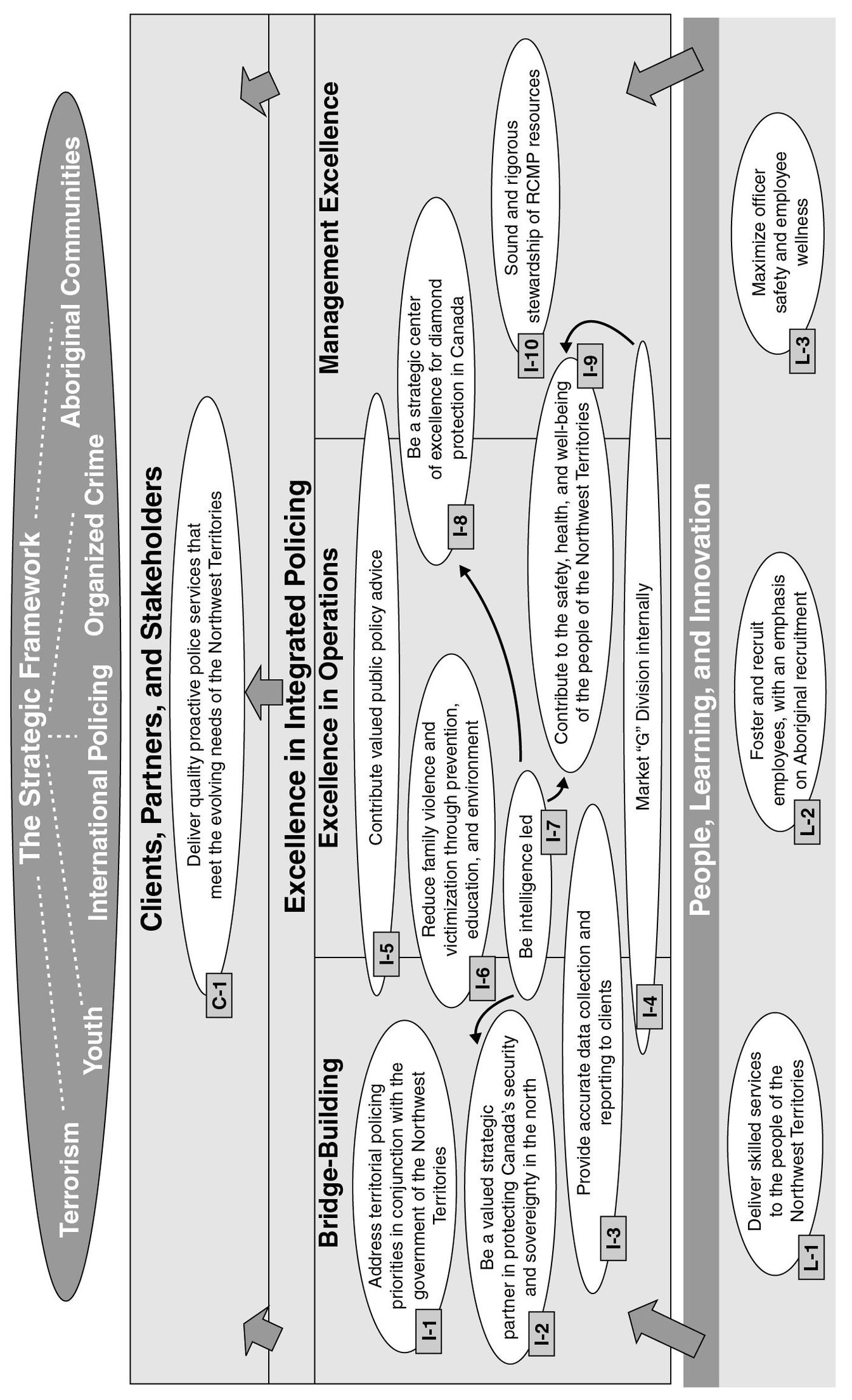

A senior-level project team at the RCMP launched a process to translate the vision and mission (“Safe homes, safe communities”) into something operational that could be understood countrywide. The project team developed a Senior Executive Committee (SEC) Strategy Map (see Figure 4-13).

Figure 4-13 Case Study: Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The top-level perspective (clients, partners, and stakeholders) captures the RCMP value proposition to the core groups it serves: funding agencies, other levels of government (both domestic and international), and citizens in direct receipt of policing services. For example, the value proposition for funding agencies was for the RCMP to “be the best managed organization in government,” while the value proposition for its local partners was to “live core values that make us a trusted partner.” Each of these objectives is tied together by a primary objective: “excel at leading-edge policing.” In essence, the RCMP value proposition is to deliver world-class, leading-edge policing services, at a reasonable cost to partners, stakeholders, and citizens.

The internal process perspective is built around three themes, each containing objectives that support the three pillars of the RCMP value proposition. The bridge-building theme articulates the communication, partnership, and alliance processes that support the goal of becoming a trusted partner. The operations theme, on which we will focus more shortly, stresses the use of the Operations Model—an RCMP methodology for being intelligence led in all activities and conduct of investigations. At the heart of this theme is excellence in service to clients, since excelling at service will increase the quality of all the policing operations. Finally, the management excellence theme supports the requirements of the funding/oversight agencies.

The people, learning, and innovation perspective captures the importance the RCMP places on providing a stimulating and safe work environment for its employees, supported by advanced technology and leadership growth.

The heart of the new policing strategy is contained within the internal operations theme, which describes five overarching corporate-level priorities that go beyond day-to-day policing activities:

- Reduce the threat and impact of organized crime

- Reduce the threat of terrorist activity in Canada and abroad

- Prevent and reduce youth involvement in crime as victims and offenders

- Effective support of international operations

- Contribute to safer/healthier Aboriginal communities

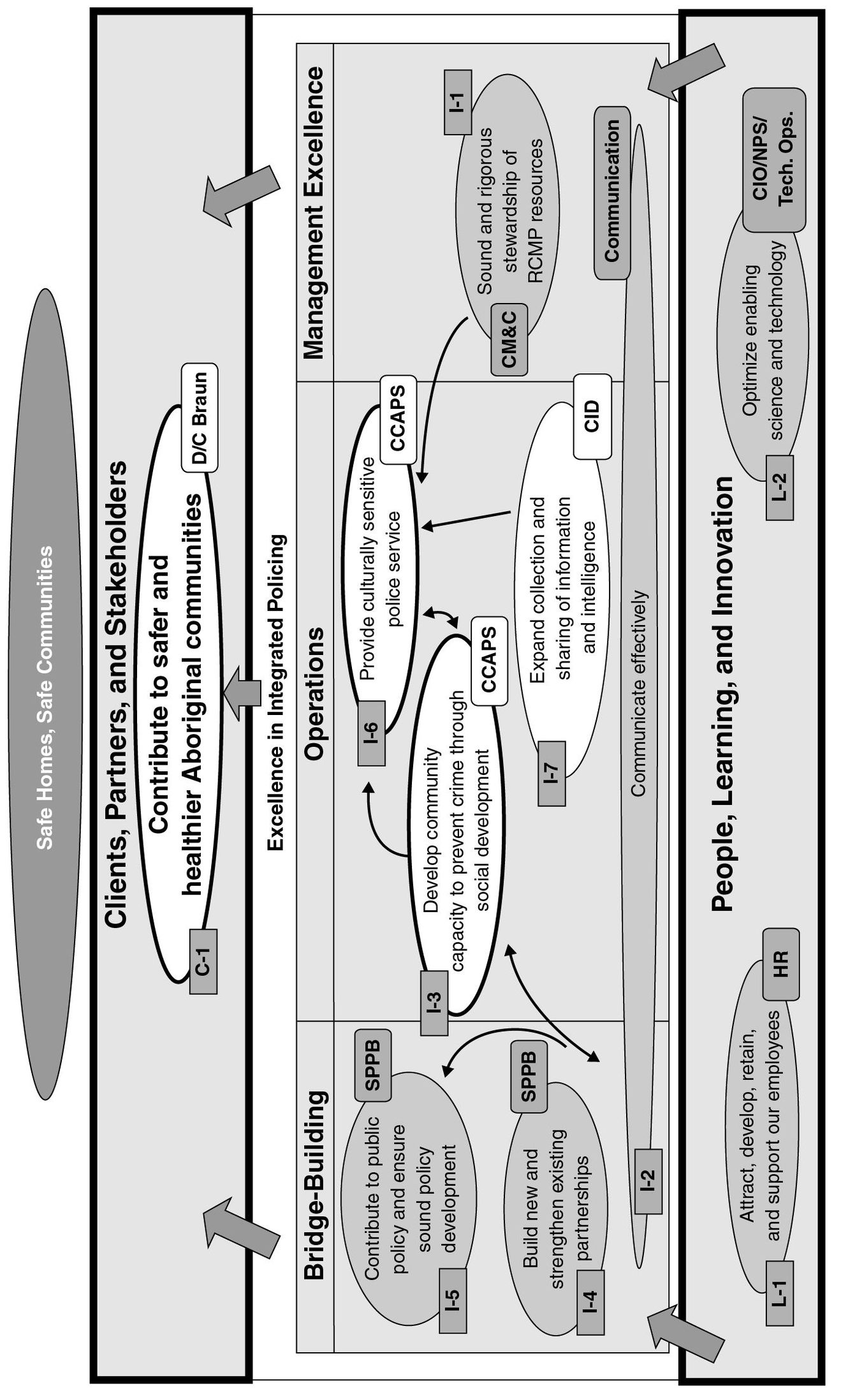

Understanding that each of the five strategic priorities required national-level strategic coordination, the RCMP developed five “virtual” Strategy Maps for each priority (Figure 4-14 shows the Strategy Map for one of the five strategic priorities: contribute to safer/healthier Aboriginal communities). Each of the five priority maps had its own measures, targets, and initiatives required to execute the strategic priorities. A senior RCMP executive was assigned as a priority champion for each strategic priority. The champion convened a panel of RCMP executives for periodic meetings to review progress against the priority’s targets, an example of how Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards can be used to manage “virtual organizations,” in this case a strategic priority for which no single organizational unit had ownership responsibility and accountability.

Figure 4-14 Strategy Map for "Safer, Healthier Aboriginal Communities"

With Strategy Maps and scorecards for the corporate-level strategy and for the five strategic priorities in place, the cascading process to local units could commence. To ensure alignment and consistent execution of these strategic priorities, each objective on the “virtual” Strategy Maps was assigned to a business line—or corporate service line—and placed on the relevant Strategy Map. The local divisional units considered the relevance of the national priorities for their divisions, then customized these high-level strategic priorities to reflect the specific realities of their operations. In addition, the local Strategy Maps incorporated the division’s normal policing responsibilities (see Figure 4-15 for an example of a division-level Strategy Map). Thus an RCMP unit in Canada’s Northwest Territory, where terrorist activity, organized crime, or international crime are rare, would not necessarily incorporate objectives for those priorities. It would definitely include objectives relating to youth involvement in crime and contributing to safer/healthier Aboriginal communities. Conversely, an RCMP unit based in Toronto might not be able to make as great a contribution to Aboriginal communities as the Northwest unit, but would include objectives related to reducing threats from organized crime, international crime, and terrorist activity. In this way, all units played a role in delivering on RCMP strategic priorities beyond their day (and night) job of local policing.

With the BSC at the heart of RCMP’s management system, the Senior Executive Committee could now stay focused on strategic priorities, knowing that the local units were responsible and accountable for day-today operations. Data on strategic objectives were updated every sixty days so senior executives could stay in touch with how their priorities were being implemented in the field.

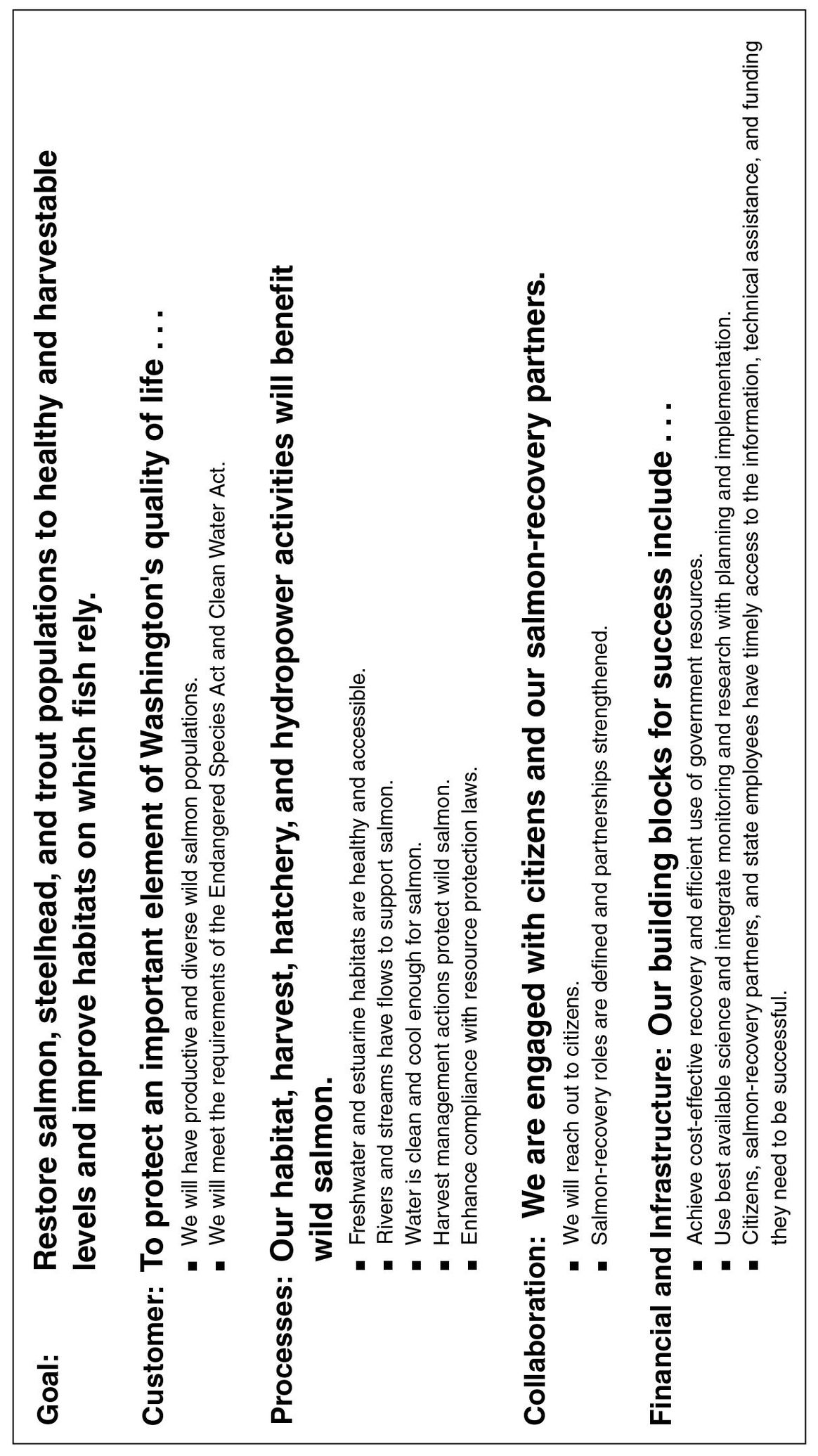

CASE STUDY: SALMON RECOVERY IN WASHINGTON STATE

RCMP is an excellent example of achieving alignment within a large public-sector agency. But some issues are beyond the scope of any single governmental agency or authority. Consider the problem of salmon recovery in Washington State. The federal government, through the Endangered Species Act, had mandated that the state make dramatic improvements in the quantity of salmon in the ocean and rivers around the state. If the U.S. government was not satisfied with the state’s recovery plan and its performance in meeting the plan, it could intervene by demolishing hydroelectric dams and stopping or severely curtailing all forestry, agriculture, hydropower production, transportation improvements, land use changes, and recreational activities, such as fishing and boating, until the state implemented a credible plan to restore salmon populations.

Figure 4-15 "G" Division Strategy Map

Governor Gary Locke had asked each agency to devise performance measures linked to salmon recovery, but he doubted that the sum of these individual, diffuse efforts would add up to the desired outcome of producing a coherent, credible, and acceptable plan to increase salmon populations. No single agency had complete control over all aspects of the environment that affected the supply of salmon. The governance structure was highly fractured and included 6 neighboring states, another country (Canada), 8 U.S. agencies, 12 state agencies, 39 counties, 277 cities, 300 water and sewer districts, 170 local water suppliers, and 27 autonomous Indian tribes whose members loved to hunt and fish. Left on their own, state agencies could set measurable objectives for outputs under their control that influenced salmon production. Yet the decentralized efforts would likely fail because the strategies of individual, decentralized agencies did not represent a coherent, comprehensive strategy.

Washington state already had an interagency strategic process under way to define an agenda for salmon recovery. From this initiative, it was a logical step to build a Balanced Scorecard for a strategic theme to preserve and enhance salmon, even though no czar of salmon existed and no single agency at any level had salmon recovery within its primary authority or responsibility. Assembling knowledgeable and interested senior managers to work on a common task enabled the salmon-recovery task force to pool the participants’ collective knowledge to create a Balanced Scorecard that would express a comprehensive and integrated strategy for salmon recovery (see Figure 4-16). What’s more, the open, transparent process built trust and commitment among the participants about how they could work within their agencies, and collectively across agency lines, to achieve the ambitious salmon recovery targets.

The agency representatives then went back to their agencies and identified performance measures, targets, programs, and initiatives that would contribute to the high-level strategic theme. The agency scorecards would include not only actions under their direct control but also, and perhaps even more important, the links they would have to make with the other government agencies, with private citizens, and with other entities for the entire effort to be a success.

Figure 4-16 Salmon Recovery Scorecard Objectives

For each Balanced Scorecard measure, the salmon-recovery team identified an executive sponsor and supporting interagency workgroup that would ensure a good data collection and reporting process for that measure. The executive sponsor also had the authority to convene meetings to discuss the initiatives that should be funded to improve the measure, and to discuss the progress and problems on the measure’s performance.

Used in this way, the Balanced Scorecard provided the mechanism by which individuals in diverse and dispersed agencies could reach a consensus about a common plan of action, and then implement the needed managerial actions: collecting and reporting data, allocating resources, conducting progress and problem-solving meetings, and adapting the strategy in light of experience and new knowledge.

While the process of strategy formulation came first, the Balanced Scorecard provided a way to begin discussions with the public about indicators of progress. More important, the scorecard provided the discipline to convene individuals from multiple organizational units to describe important strategic themes (in effect, a virtual organization). The scorecard included both the outcomes desired (how to measure success for the strategic theme) and the performance drivers, especially in the internal processes and learning and growth required for the group to achieve the desired outcomes of the strategic theme. Individual organizational units then defined their own strategies and scorecards, including their respective contributions to the objectives articulated in the strategic theme’s scorecard. And the theme-based scorecard provided the mechanism to convene meetings in which representatives from diverse agencies and constituencies could solve problems collectively rather than from within agency silos.

SUMMARY

An enterprise can achieve significant economies of scale when it centralizes key processes—such as production, distribution, purchasing, human resource management, or risk management—to serve its diverse business units. The decision to centralize a shared process is made at corporate headquarters and becomes a component of the enterprise value proposition. The enterprise also creates value when it encourages business units to integrate their previously separate offerings to deliver complete solutions to targeted customers.

An enterprise can enhance its human capital and its employees’ career development by providing opportunities for employment experience in diverse business units and geographic regions. It can also promote the sharing of knowledge and best practices throughout all its business and support units so that new ideas can be rapidly transmitted and assimilated within the enterprise far faster than if each unit had to develop or learn such ideas by itself.

Finally, the enterprise creates synergies when it articulates strategic themes that enhance links and coordination among multiple business units. The strategic themes are articulated on the enterprise Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard. They provide an alternative to a matrix structure organization, because business unit managers now have objectives on their Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards that relate both to their own local objectives and to the enterprise priorities. In effect, business unit managers operate as dual citizens, serving both their local units and the corporate entity.

In the public sector, a Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard can be developed for high-level objectives—such as improving salmon recovery, national intelligence, homeland security, or drug interdiction—that require the coordination and integration of the efforts of many entities if the public benefit is to be achieved.

NOTES

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004), 18–28.

For more information on the organization change agenda, see ibid., Chapter 10; and “Measuring the Strategic Readiness of Intangible Assets,” Harvard Business Review (February 2004).

Talk given at North American Summit, Balanced Scorecard Collaborative, October 2003.

John Bronson, Speaking at BSCol Conference on Human Resource Alignment, Naples, Florida, February 2002.

“Motivate to Make Strategy Everyone’s Job,” Balanced Scorecard Report (November–December 2004).

HBR article - 2004

SHRM research - 2002

TK

“How to Mobilize Large, Complex Organizations Using the Balanced Scorecard: An Interview with Craig Naylor of DuPont Engineering Polymers,” Balanced Scorecard Report (September–October 2000): 11–13.