CHAPTER NINE

MANAGING THE ALIGNMENT PROCESS

ALIGNMENT IS NOT a one-time event. The initial project phase of implementing an enterprise-wide Balanced Scorecard program aligns corporate-level strategy with business and support unit strategies. This sets the stage for achieving performance synergies.

Change, however, is constant—in the industry, among competitors, in the regulatory and macroeconomic environment, and in technology, customers, and employees. Strategies and their implementation must therefore continually evolve. An aligned organization at one time will soon become unaligned. The second law of thermodynamics teaches us that entropy (disorder) continually increases. New energy must be continually pumped into a system if it is to remain aligned and coherent. In this chapter, we describe the process of managing and sustaining organizational alignment.

CREATING ALIGNMENT

Sometime in the middle of their fiscal year, almost all enterprises conduct a multiday off-site meeting organized by the strategic planning department. At this meeting the executive leadership team reviews and updates the company’s strategy in light of changing circumstances and the new knowledge gained since the last strategy was formulated. The update involves many of the traditional techniques of strategic planning, including environmental scans, SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, competitive analysis, five-forces models, and scenario planning.

Subsequently, business units and shared-service departments do their own annual strategy planning updates. The strategies of these organizational units, however, are often done in isolation, uninformed by the corporate strategy, and therefore they do not reflect how the units must work together to achieve integration and synergy. These fragmented, unaligned management processes explain why most enterprises encounter great difficulty in implementing their strategies.

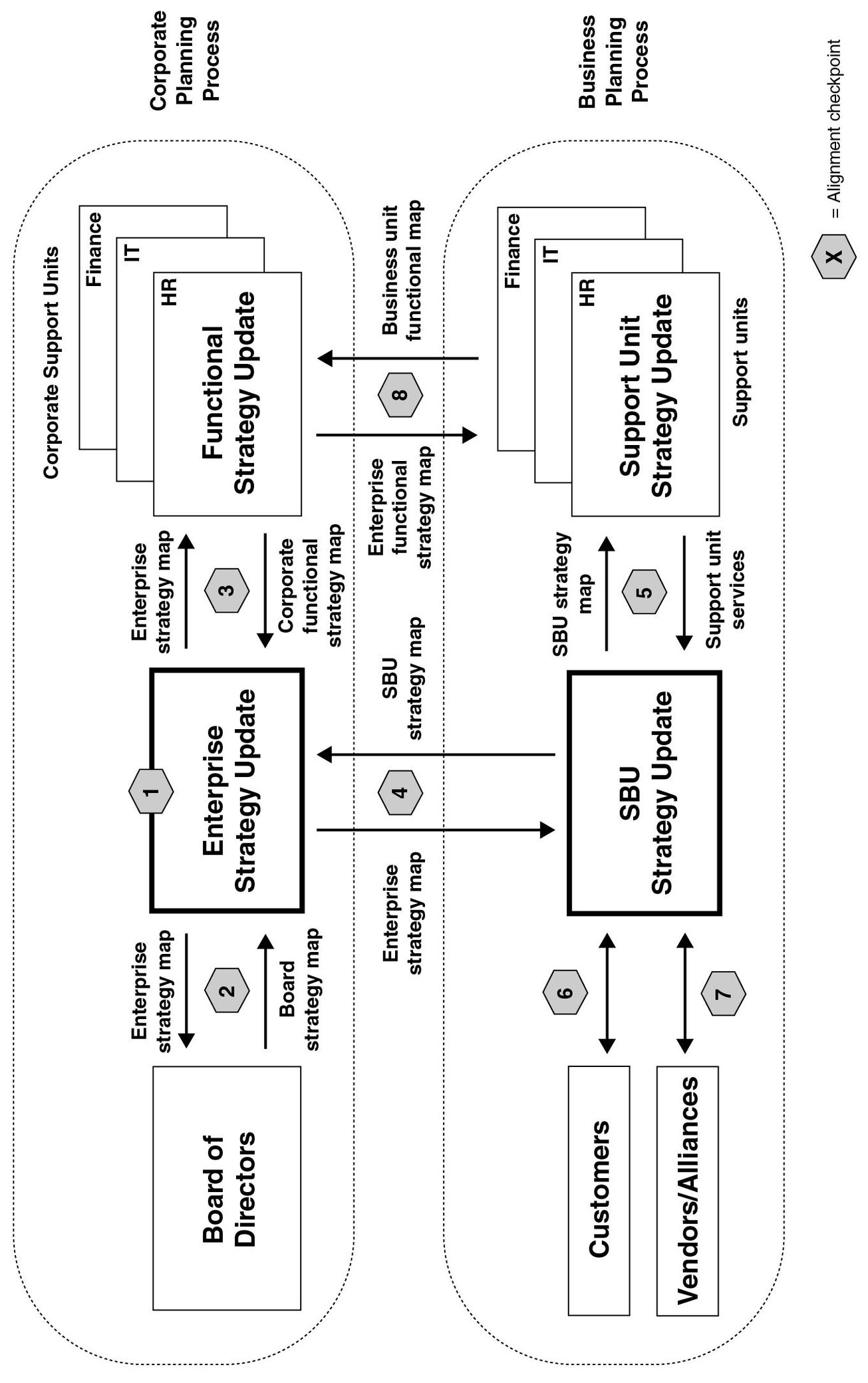

A comprehensive and managed alignment process helps the enterprise to achieve synergies through integration. We have identified eight alignment checkpoints (see Figure 9-1) from the practices of successful Balanced Scorecard users. If an organization is aligned at each of the eight checkpoints, all its initiatives and actions are directed toward common strategic priorities:

- Enterprise value proposition: The corporate office defines strategic guidelines to shape strategies at lower levels of the organization, as described in Chapters 3 and 4.

- Board and shareholder alignment: The corporation’s board of directors reviews, approves, and monitors the corporate strategy, as described in Chapter 7.

- Corporate office to corporate support unit: The corporate strategy is translated into those corporate policies—such as standardized practices, risk management, and resource sharing—that will be administered by corporate support units, as discussed in Chapter 5.

- Corporate office to business units: The corporate priorities are cascaded into business unit strategies, as discussed in Chapters 3, 4, and 6.

- Business units to support units: The strategic priorities of the business units are incorporated in the strategies of the functional support units, as discussed in Chapter 5.

- Business units to customers: The priorities of the customer value proposition are communicated to targeted customers and are reflected in specific customer feedback and measures, as discussed in Chapter 8.

- Business units to suppliers and alliance partners: The shared priorities for suppliers, outsourcers, and other external partners are reflected in business unit strategies, as discussed in Chapter 8.

- Business support units to corporate support: The strategies of the local business support units reflect the priorities of the corporate support unit, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Figure 9-1 Building Alignement Chackpoint into the Planning Process

As a specific example of an aligned corporation, let’s revisit the Ingersoll-Rand story told in several earlier chapters. Recall that Ingersoll-Rand’s new corporate strategy (depicted in Figure 3-4) was to shift from being a holding company of product-centered business units to one providing branded, integrated customer solutions that cut across traditional business unit lines. IR’s new enterprise value proposition illustrates fulfillment of checkpoint 1. The strategy shift required a new culture of teamwork and knowledge sharing, new competencies, and new leadership values. The cultural shift was facilitated by the corporate human resources organization, as described in Chapter 5. Figure 5-10 illustrates how Ingersoll fulfilled checkpoint 3 by translating the corporate business strategy into a corporate human resources strategy focused on leadership development, cross-business teamwork, and realignment of personal goals to the new strategy. Once the corporate-level alignment was achieved, Ingersoll’s corporate HR group cascaded its template to HR groups in the five major business groups, fulfilling checkpoint 8. This process aligned local HR groups located within business units with corporate HR priorities.

Each of Ingersoll’s business groups created a Strategy Map that reflected the dual citizenship theme of achieving local excellence while delivering on corporate-level themes (see Figure 3-4), fulfilling alignment checkpoint 4. Ingersoll also began to communicate the new corporate strategy with its board and shareholders in its annual report (see Figure 7-10), fulfilling alignment checkpoint 2. Thus Ingersoll successfully passed all five corporate planning alignment checkpoints shown in the upper half of Figure 9-1.

The single most important component of the organization alignment occurs at alignment checkpoint 4: the linkage of business unit strategies to the enterprise value proposition. Many organizations take explicit actions to monitor this alignment. At Canon, USA, the corporate planning group creates sticky notes that show every objective from its six main business and support units’ Strategy Maps. Then it posts the business and support unit objectives on the corporate map to see how well each corporate objective is supported. Next, it analyzes the results to see why some objectives have strong support and others have weak support. In this way, the planning group not only monitors alignment but also identifies cross-functional and cross-unit links within the strategy so that it can create value-sharing communities across the company.

During the planning process at St. Mary’s/Duluth Clinic Health System, the vice president of strategic alignment reviews the Strategy Maps of various divisions and departments to ensure alignment among them and also with the corporate strategy. The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi, discussed in Chapter 4 (Figure 4-1), explicitly identifies objectives on its corporate Strategy Map that are common across all business units. This provides a point of reference for the director of the corporate planning group to ensure that business unit strategies align with corporate themes, such as risk management and cost reduction.

In each of these companies, a corporate-level group managed an explicit process to ensure that business unit strategies were aligned vertically with corporate priorities and horizontally with the strategies of related business units.

The implementation of business unit strategy has three other alignment checkpoints. In Chapter 5, we describe how to achieve checkpoint 5 by introducing the portfolio of strategic support services, which translates the priorities of a business unit Strategy Map into specific support unit programs and initiatives. Figures 5-3, 5-4, and 5-5 illustrate how Handleman built tight links between business units’ strategy and the desired human resources support.

In Chapter 4, we show how IBM Learning (Figure 4-8) developed business unit Strategy Maps to align its training and learning services with business unit strategy. In both the Handleman and the IBM cases, the companies introduced explicit processes to align the strategies of key support units with value creation in business units, as required by alignment checkpoint 5.

Companies can also introduce explicit measures and processes to align with their customers and suppliers (checkpoints 6 and 7). For example, as discussed in Chapter 8, Rockwater developed scorecards jointly with its top ten customers to define explicitly the value proposition desired by each customer. Subsequent quarterly reviews of these scorecards with customers helped to strengthen the bonds and make Rockwater an industry leader. In Chapter 1, Sport-Man, Inc.’s purchasing department (see Figure 1-7) used a similar structure to create strong alignment with the company’s suppliers, which manufacture and deliver products to Sport-Man’s retail outlets.

In summary, the planning processes at corporate units and in business and support units set priorities, allocate resources, and—the new task—create alignment throughout the enterprise. Organizations create alignment by embedding the eight alignment checkpoints into their planning processes. Having created alignment through the planning process, organizations face the remaining question: how to manage and sustain alignment on an ongoing basis.

MANAGING AND SUSTAINING ALIGNMENT

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. These are the words we live by. We developed the Balanced Scorecard so that organizations can measure and therefore more effectively manage strategic processes such as customer acquisition, customer retention, new product development, and employee competency development. If we wish to manage the new alignment process, we should—to be consistent with our message—identify alignment measures.

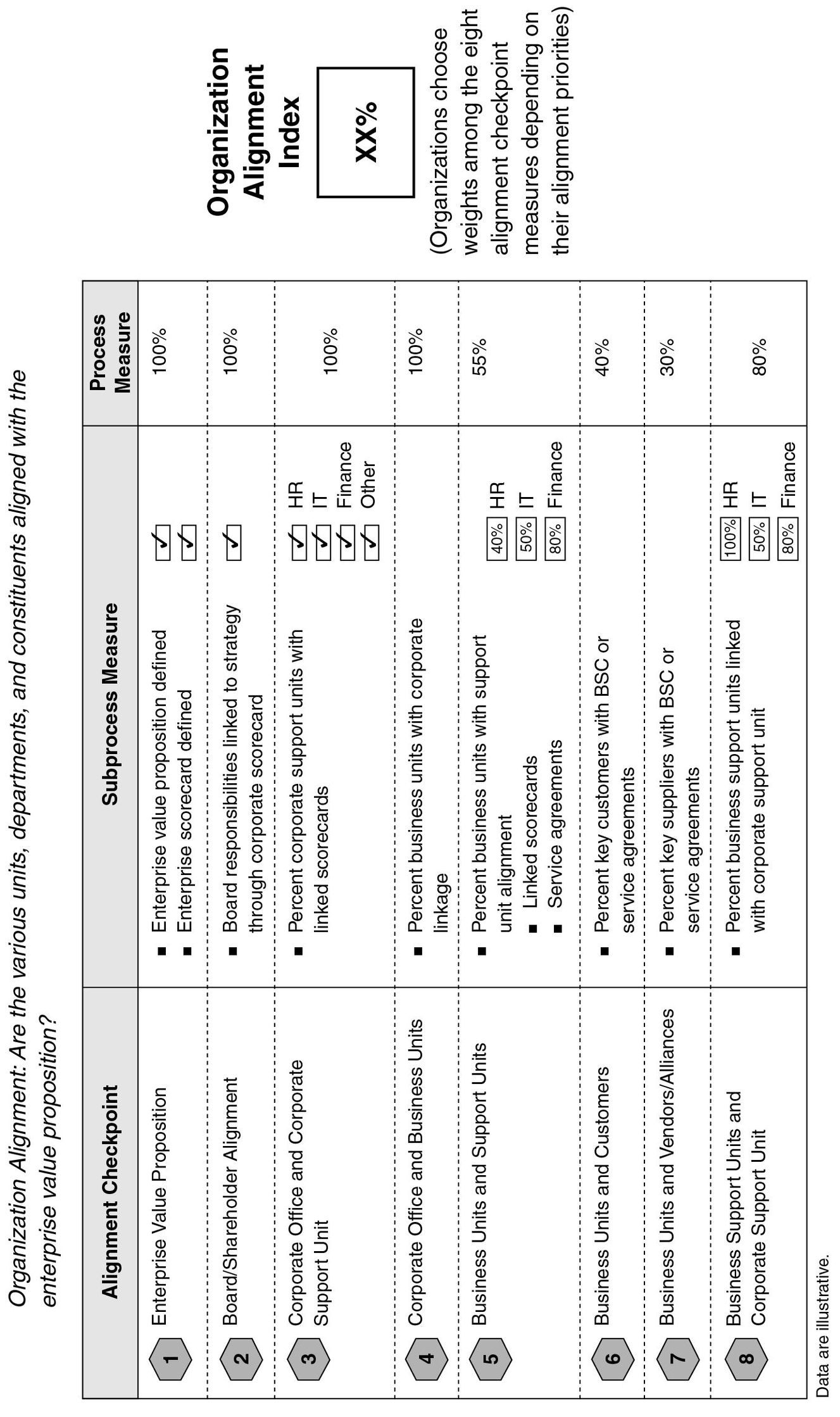

Figure 9-2 shows the development of alignment measures for each of the eight alignment checkpoints. Organizations can aggregate these measures into an organization alignment index by choosing weights specific to their priorities and beliefs about where synergistic benefits are most likely to arise.

The proposed measures are process—not outcome—measures. The corresponding outcome measures—such as the percentage of business units that have achieved six sigma quality levels or the percentage of business units achieving their targets for retention of key customers—should appear on the corporate scorecard. The process measures monitor the quality of the alignment process itself. Our theory of alignment predicts that a superior organization alignment process leads to high achievement of the corporate outcome measures.

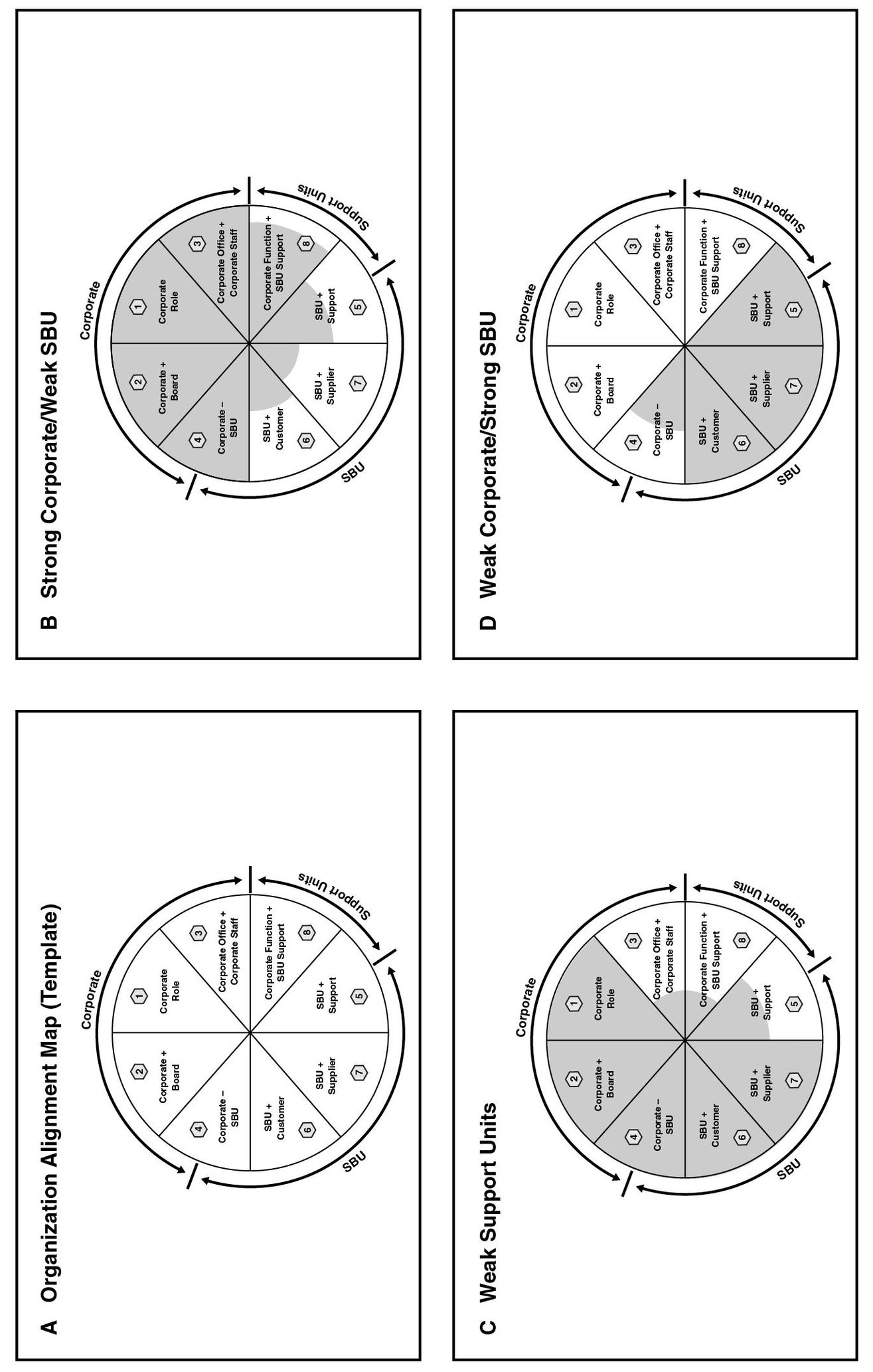

The alignment checkpoint metrics, along with the subprocess measures (see the middle column of Figure 9-2), provide useful feedback about the performance of the alignment process. We can develop an overall picture of the health of and the issues surrounding alignment by displaying the individual checkpoint measures on an alignment map, as shown in Figure 9-3. Panel A, in the upper-left quadrant, shows the starting point—a blank template that condenses the eight alignment checkpoints into three domains: corporate, business units, and support units. The three other panels depict situations where organizations typically fall short in the alignment process.

Panel B, in the upper-right quadrant, illustrates an alignment program with strong corporate leadership but weak implementation in the business and support units. The corporate strategy has been defined and translated into an enterprise value proposition (checkpoint 1), and the strategy has been reviewed and approved by the board (checkpoint 2). The strategy has been translated to the corporate staff departments (checkpoint 3), which in turn have provided guidelines to support departments in the business units (checkpoint 8). Corporate has made serious efforts to translate its strategic priorities in the enterprise value proposition to the business units (checkpoint 4), but the business units do not share this passion. Execution at the business unit level (checkpoints 5, 6, and 7) is weak. Many of the potential benefits of the corporate program have yet to be realized.

Figure 9-2 Measuring Organization Alignment

Figure 9-3 Organization Alignement Maps

Panel C, in the lower-left quadrant, describes an alignment process characterized by strong execution at the corporate and business unit levels but weak implementation by the support units. The problem begins with a weak link at the corporate level. Corporate has not emphasized the translation of its priorities to the corporate staff departments (checkpoint 3), and corporate staff has not been able to communicate corporate priorities to the business support units (checkpoint 8). The local support units, therefore, have not been responsive to business unit requirements and therefore cannot support their strategies.

The fourth example, Panel D in the lower-right quadrant, describes a situation that is frequently encountered when the BSC performance management program is initiated in a local business unit. Alignment within the business units is excellent, with strong links to customers (checkpoint 6), suppliers (checkpoint 7), and the local support units (checkpoint 5). The business unit has attempted to integrate its strategy with what it perceives to be corporate strategy and priorities, but without adequate leadership and guidance from the corporate headquarters, it has yet to link with the strategies of other business units and create synergies with them (checkpoint 4). The business unit’s support units also suffer from the lack of strategic guidance from their corporate support units (checkpoint 8).

The alignment map provides a simple picture of the current status of organization alignment, and it summarizes the detailed and actionable measures selected by the enterprise to monitor the performance of its alignment processes.

ACCOUNTABILITY

The final building block of managing organization alignment is accountability. Just as the chief financial officer is accountable for running budgeting and the vice president of human resources is accountable for running employee performance management, a senior executive should be responsible for running the alignment process. Unless someone is accountable, alignment will not happen.

Several organizations have started to establish an accountability structure for organization alignment. J. D. Irving, a multibillion-dollar Canadian conglomerate, created a position called alignment champion to help business units implement the various change programs in their strategies. St. Mary’s/Duluth Clinic, a health-care provider in northern Minnesota, created a position of vice president of strategic alignment. The executive in this position facilitates the execution of the organization’s strategy. By placing this position at the vice president level, the CEO sent the message that ensuring organization alignment was a high priority for him. Canadian Blood Services (formerly the Canadian Red Cross) created an alignment council at the outset of its Balanced Scorecard program to ensure that the strategies of corporate and various business units would be consistent and integrated.

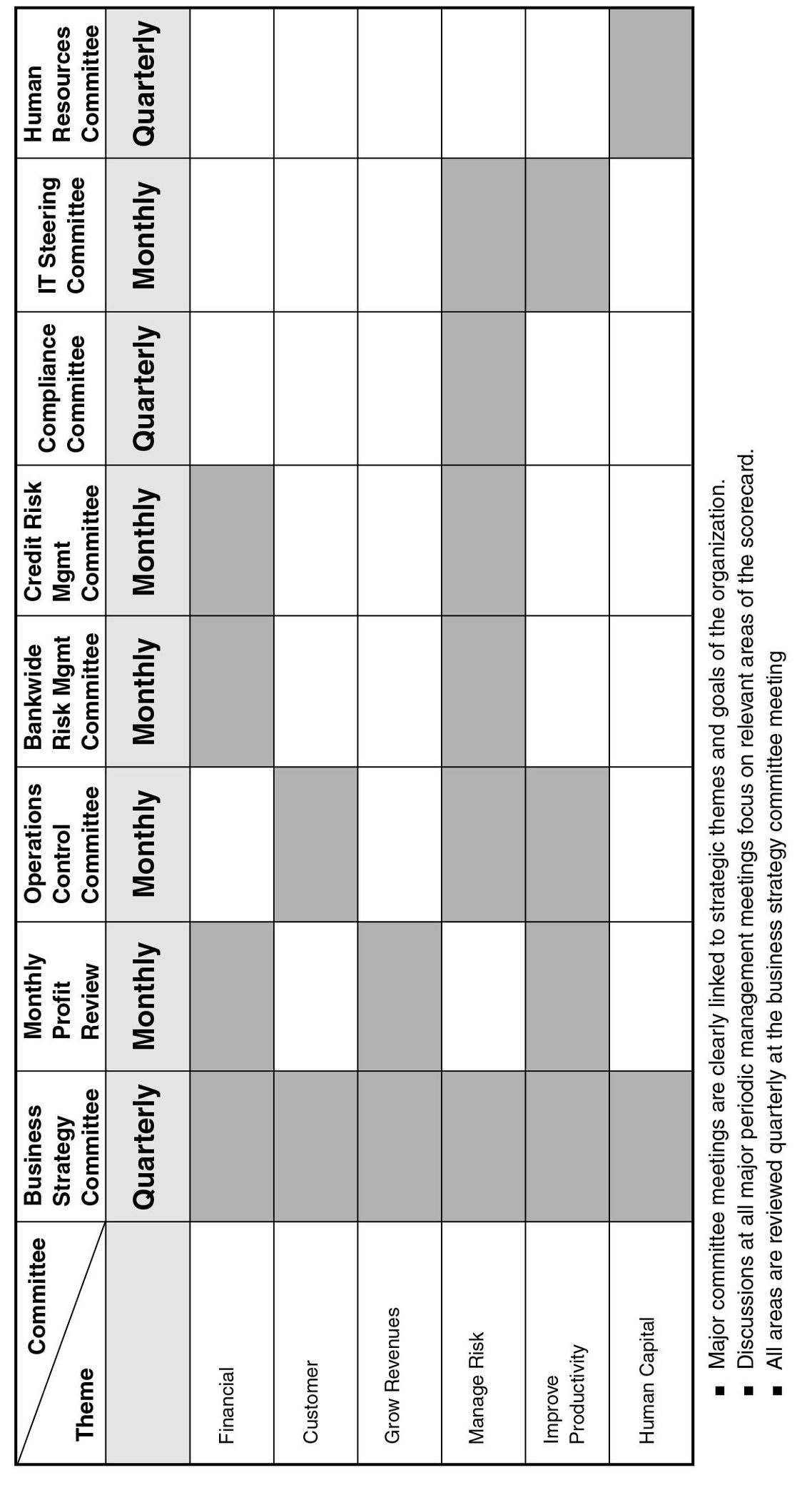

The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi, Headquarters for the Americas (BTMHQA), discussed in Chapter 6, introduced a sophisticated scheme to create alignment through its governance process. As shown in the first column of Figure 9-4, the bank’s strategy was built on six strategic themes: grow revenue, manage risk, improve productivity, align human capital, and enhance financial performance and customer satisfaction.

The bank already had eight committees involved in some aspect of organizational governance, as shown in the column headings in Figure 9-4. The bank asked each committee, in addition to its traditional duties, to monitor the strategy themes within its domain of responsibility. For example, the credit risk committee, at its monthly meeting, discussed and acted on the financial and risk-management strategy themes. At the monthly meeting of the operations control committee, members monitored the customer, risk-management, and productivity themes. On a quarterly basis, the business strategy committee reviewed all six strategy themes. With this formal assignment of responsibilities, BTMHQA embedded alignment and accountability in its core management committees and processes.

The organizations in these examples addressed components of the alignment process by assigning accountability to specific individuals or committees. Although this is a move in the right direction, we believe that alignment and accountability must be built into all the key management processes undertaken throughout the year.

We have recently observed in practice a new role emerging in organizations to manage strategy execution in a comprehensive and integrated way. Examples are the Chrysler Group, Crown Castle, U.S. Army, and St. Mary’s/Duluth Clinic. We call this new role the office of strategy management (OSM). The new office is often the successor to the Balanced Scorecard project team. The OSM represents the natural evolution of the Balanced Scorecard from a project to an ongoing alignment and governance process.1 One of the key roles for the OSM is to manage the alignment process, with the following job description.

Figure 9-4 Alignment and Accountability at Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi, Americas

Organization Alignment

The OSM helps the entire enterprise gain a consistent view of strategy, including the identification and realization of corporate synergies. The office of strategy management facilitates the development and cascading of Balanced Scorecards at different hierarchical levels of the organization. Its responsibilities for the alignment process include the following:

- Defining, on the corporate scorecard, the synergies to be created through cross-business integration at lower organization levels

- Linking business unit strategies and scorecards to the corporate strategy

- Linking support unit strategies and scorecards to the strategic objectives of the business units and corporate

- Linking external partners, such as customers, suppliers, joint ventures, and the board of directors, to the organization’s strategy

- Organizing the executive leadership team’s review and approval of the scorecards produced by the business units, support units, and external partners

Alignment, like the other strategy execution processes, crosses organization boundaries. To be executed effectively, alignment requires the integration and cooperation of individuals from various organizational units. This poses a dilemma because most organizations have no natural home for cross-business processes. Organizations are built on business units or functions that operate in isolation from each other. Those organizations that have instituted an office of strategy management address this problem by creating a small group of individuals to manage the cross-business processes, including alignment, that are critical to successful execution of strategy.

SUMMARY

Any interface where two disparate organizations—corporate, business unit, support unit, customer, or supplier—come together represents a potential source of value creation through alignment. The enterprise value proposition and the cascading process of Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards are the mechanisms that unleash and capture this incremental value.

By its very nature, alignment requires cooperation across organizational boundaries, and therefore the process must be managed proactively, preferably by an individual or organizational unit that is accountable for the success of the alignment. Assigning responsibility and accountability for an effective organizational alignment process is a natural task for the new office of strategy management, which can coordinate the multiple planning processes and ensure, at least annually, that all the alignment checkpoints are achieved.

NOTES

The office is described in more detail in R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, “The Office of Strategy Management,” Harvard Business Review (October 2005): 72–80.