CHAPTER 10

TOTAL STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT

THE BALANCED SCORECARD, since its introduction in 1992, has evolved into the centerpiece of a sophisticated system to manage the execution of strategy. The effectiveness of the approach is derived from two simple capabilities: (1) the ability to clearly describe strategy (the contribution of Strategy Maps) and (2) the ability to link strategy to the management system (the contribution of Balanced Scorecards). The net result is the ability to align all units, processes, and systems of an organization to its strategy.

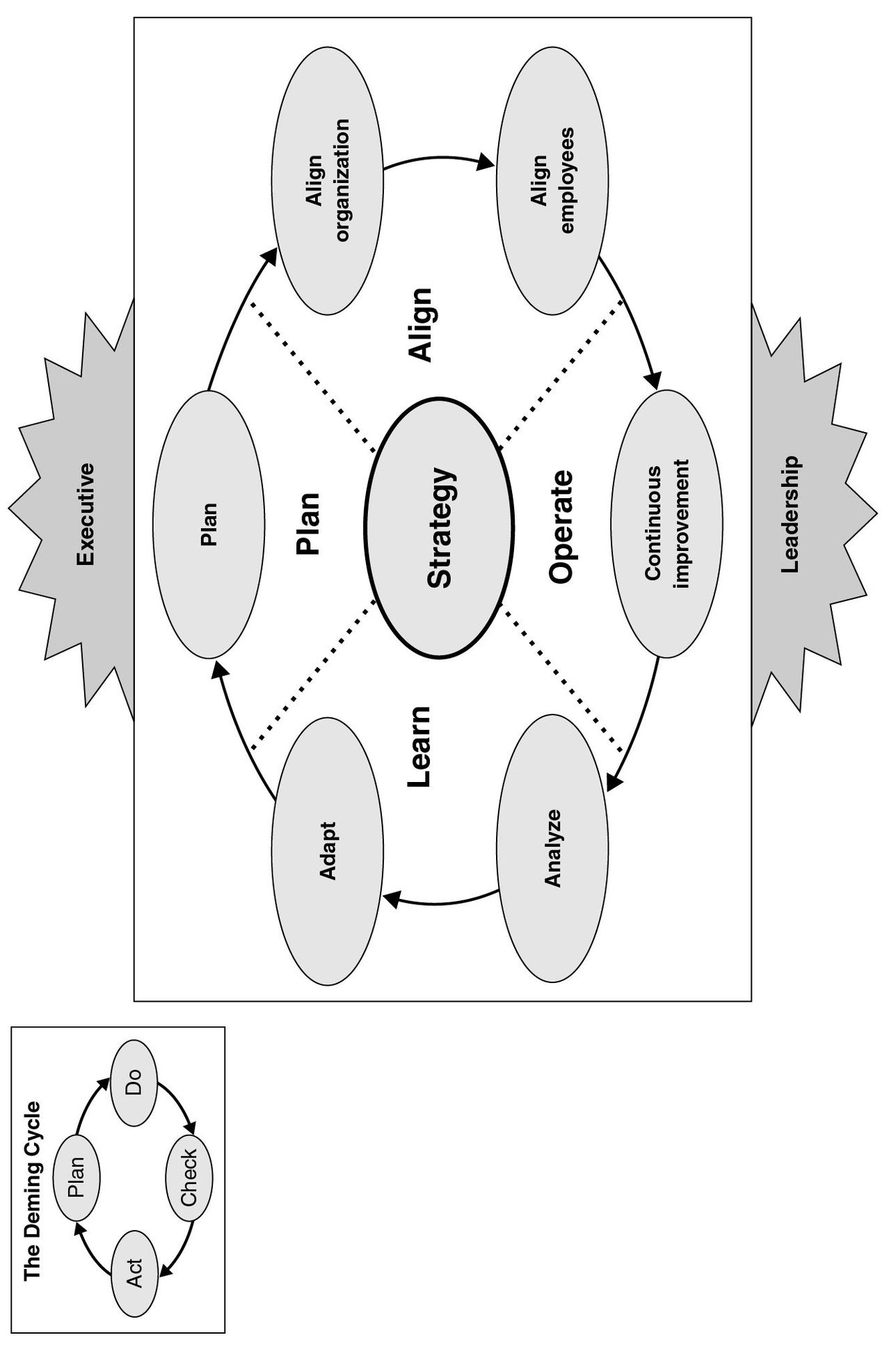

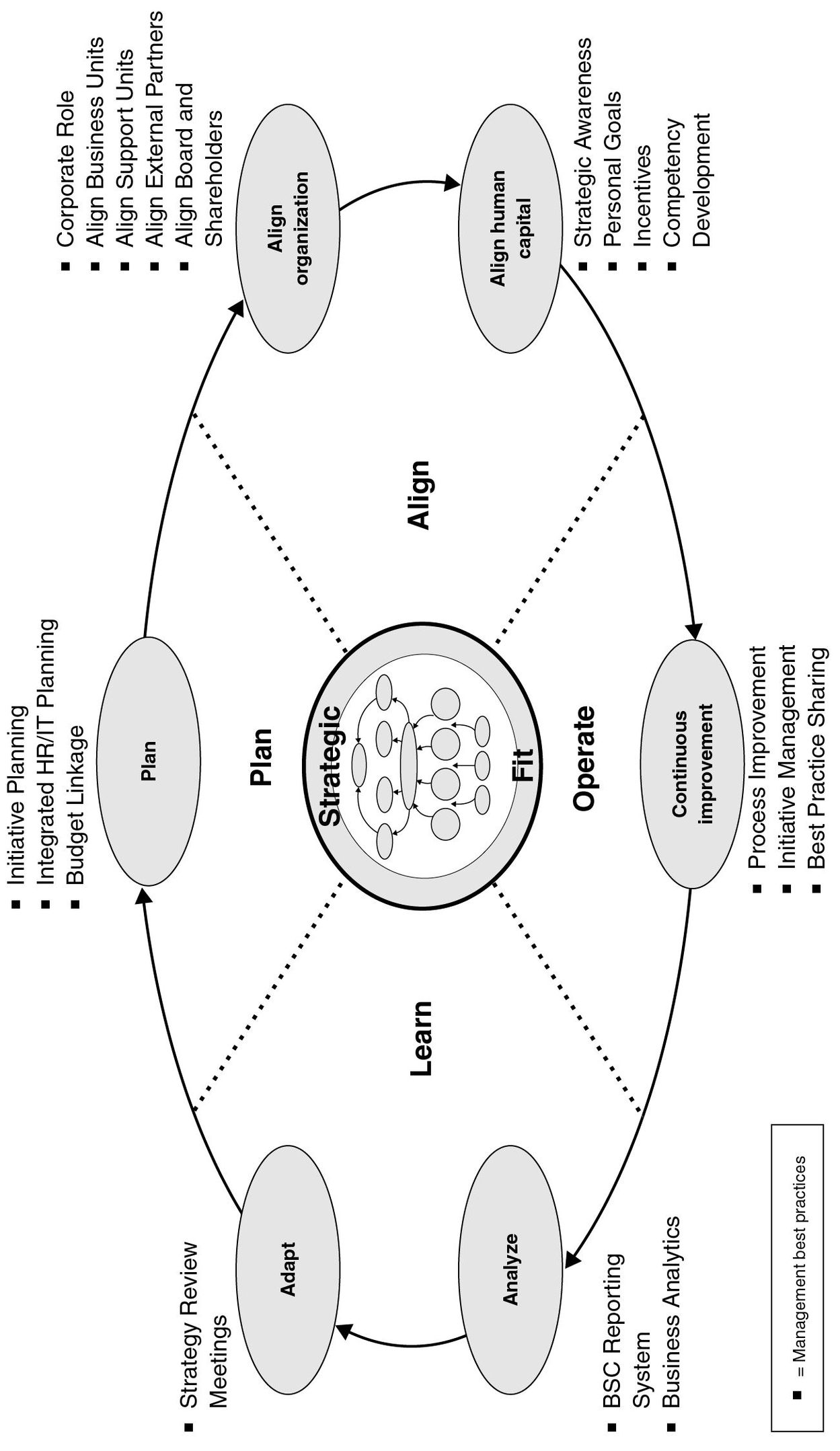

Figure 10-1 describes a simple management framework for strategy execution. The approach adds several important features to the classic “plan-do-check-act” closed-loop, goal-seeking process introduced by Deming in the quality movement.1

- Strategy is explicitly identified as the focal point of the management system (as opposed to “quality”).

- Alignment is identified as an explicit part of the management process. Executing strategy requires the highest level of integration and teamwork among organizational units and processes.

- Executive leadership is a necessary condition for successful strategy execution. Managing strategy is synonymous with managing change. Without strong executive leadership, constructive change is not possible.

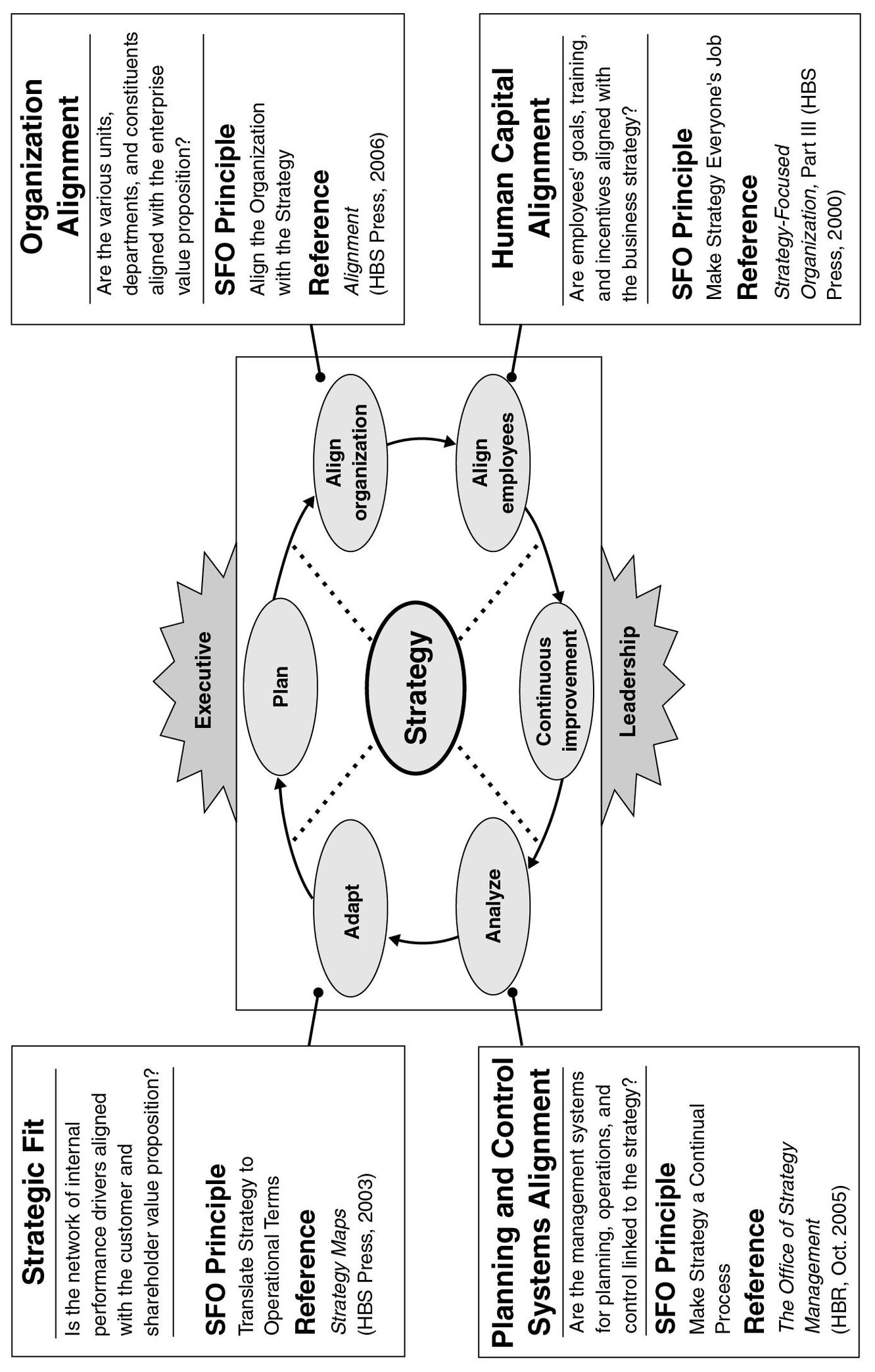

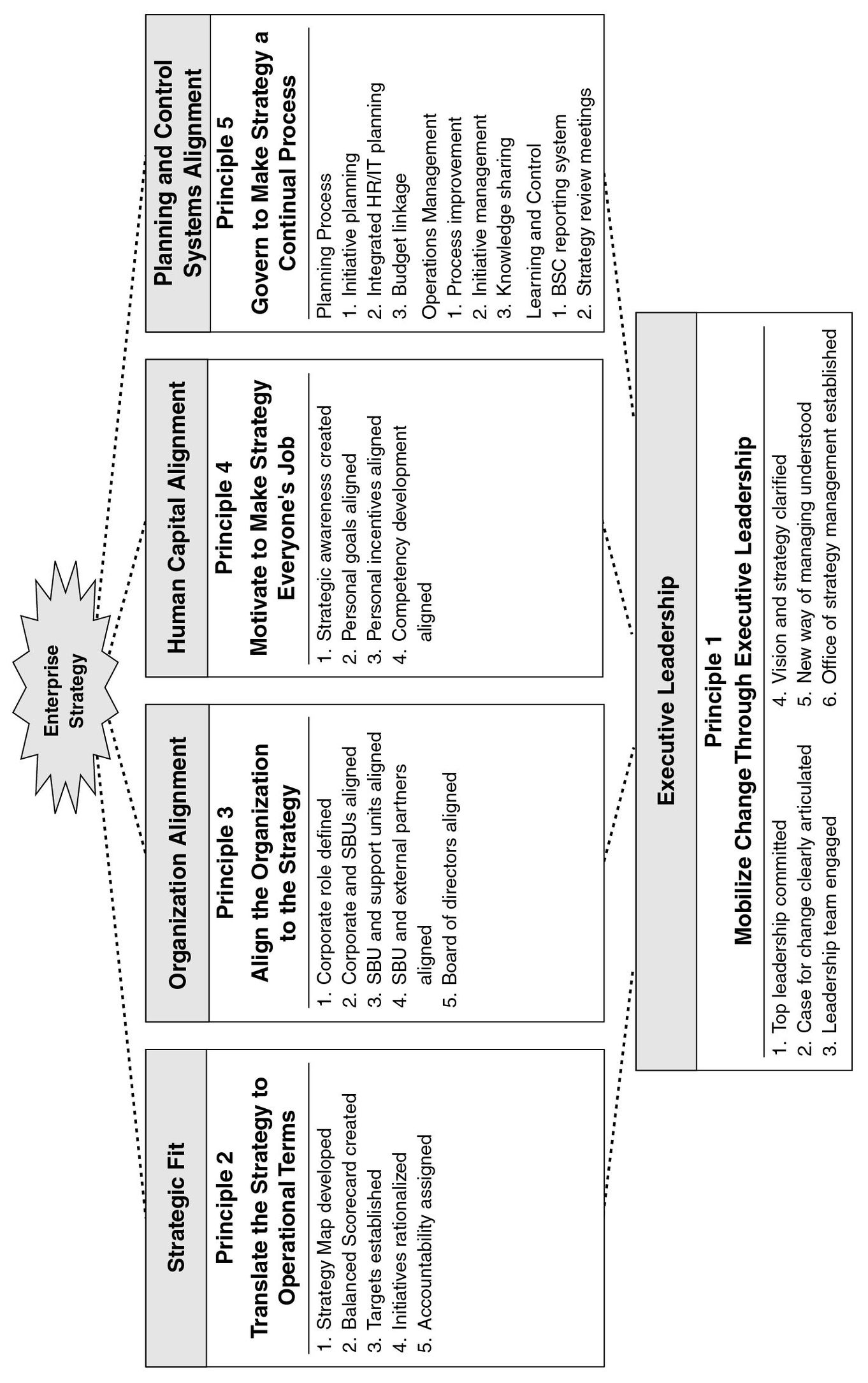

The core idea is that strategy is at the center of the management system. With the strategy clearly defined, all components of the management process can be designed to create alignment. As shown in Figure 10-2, alignment has four components: strategic fit, organization alignment, human capital alignment, and alignment of planning and control systems. We look at each of these in turn.

Figure10-1 The BSC Strategy Execution Framework

STRATEGIC FIT

Strategy consists of numerous high-impact activities that ultimately must be resourced and coordinated through the management system. A strategy can be described by a detailed set of objectives and initiatives. Strategic fit, a concept introduced by Michael Porter, refers to the internal consistency of the activities that implement the differentiating components of the strategy.2 Strategic fit exists when the network of internal performance drivers is consistent and aligned with the desired customer and financial outcomes. Strategy Maps, extensively described in one of our previous books, provide a mechanism to explicitly identify and measure the internal alignment of processes, people, and technology with the customer value proposition and customer and shareholder objectives.3 4 5

ORGANIZATION ALIGNMENT

The subject of this book—organization alignment—explores how the various component parts of an organization synchronize their activities to create integration and synergy. Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards provide executives with a mechanism to describe strategy at each level and to communicate it from one level to the next. They also measure the extent to which goals requiring cross-organization teamwork are being addressed among organizational units.

HUMAN CAPITAL ALIGNMENT

Strategy is formulated at the top, but it must be executed at the bottom—by machine operators, call center personnel, delivery truck drivers, salespeople, and engineers. If employees don’t understand the strategy or are not motivated to achieve it, the enterprise’s strategy is bound to fail. Human capital alignment is achieved when employees’ goals, training, and incentives become aligned with business strategy.

Figure 10-2 Creating Total Strategic Alignment

PLANNING AND CONTROL SYSTEMS ALIGNMENT

The organization’s planning, operations, and control processes allocate resources, drive action, monitor performance, and adapt the strategy as required. Even if enterprises develop a good strategy and align their organizational units and employees to it, misaligned management systems can inhibit its effective execution. Planning and control systems alignment exists when the management systems for planning, operations, and control are linked to the strategy.

Our previous book Strategy Maps and this book have dealt in depth with the first two alignment components: strategic fit and organization alignment. To provide a complete alignment picture, we close Alignment with brief descriptions of the two remaining components: aligning human capital and aligning management systems.

ALIGNING HUMAN CAPITAL

Alignment programs cannot deliver results unless employees have a personal commitment to help their enterprise and unit achieve strategic objectives. The human capital alignment process must gain the commitment of all employees to the successful implementation of strategy.

Psychologists have identified two forces for motivating people. Intrinsic motivation occurs when people engage in an activity for its own sake. They get pleasure from performing the activity; it contributes to their satisfaction and creates outcomes that they value. Extrinsic motivation arises from the carrot of external rewards or the stick of avoiding negative consequences. Positive rewards include praise, promotions, and financial incentives. The threat of negative consequences can also motivate; employees will strive to avoid criticism from a supervisor, a loss in prestige from failing to achieve a public target, or a loss of position or employment.

Intrinsic motivation is generally associated with those who engage in more entrepreneurial and creative problem solving; compared with those who are motivated only by extrinsic rewards or consequences, intrinsically motivated employees consider a wider range of possibilities, explore more choices, share more knowledge with coworkers, and pay more attention to complexities, inconsistencies, and the long-term consequences in their environment. Extrinsic motivation focuses employees on actions to achieve a reward or avoid punishment. Extrinsically motivated employees tend not to question the measures used to evaluate their performance. They assume that higher-level managers have gotten the measures correct and that their job is to move the measures in the desired direction and achieve the targets managers have established for the measures.

Although psychologists generally advocate the benefits of intrinsic over extrinsic motivation, companies have found that these two motivating forces are complementary and not competitive. In fact, the bestperforming companies use both forces to align employees with organizational success.

Communicate and Educate to Create Intrinsic Motivation

We opened this book with a metaphor of rowers in a shell, attempting to achieve alignment as they row down the Charles River separating Boston and Cambridge. These individuals make huge sacrifices to compete. They wake up early on wintry mornings to exercise and practice. They commit several hours each day to the activity. How much do they get paid for it? Nothing. The athletes sacrifice and work hard because they enjoy preparing for the contest, working with their teammates, and competing to win. Imagine the energy released if a company could get its employees similarly motivated—working hard individually and in teams to help the enterprise be the best in a global competition.

Leaders create intrinsic motivation by appealing to employees’ desire to work for a successful organization that makes a positive contribution to the world. Employees want to take pride in the organization in which they spend much of their waking lives. Employees should understand how the success of their organization benefits not only shareholders but also customers, suppliers, and the communities in which it operates. Employees should feel that their organization functions both efficiently and effectively. No one enjoys working for a failing, underperforming enterprise. They should be reassured that the organization does not squander resources in pursuit of its mission. Poorly functioning organizations, bureaucracies that bog down decision making, and turf battles arising from the narrow-mindedness often spawned by functional silos are visible to everyone and demoralizing to all.

Communication of vision, mission, and strategy is the first step in creating intrinsic motivation among employees. Executives can use the Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard to communicate strategy—both what the organization wants to accomplish and how it intends to realize its strategic outcomes. Objectives and measures in the financial and customer perspectives of the Balanced Scorecard describe the outcomes the organization seeks with the entities that supply funds: shareholders and customers (donors and constituents, for nonprofit and public-sector organizations). Objectives and measures in the internal and learning and growth perspectives describe how employees, suppliers, and technology are aligned around critical processes that deliver superior value propositions for customers and shareholders while meeting community expectations. Taking all the objectives and measures together provides a comprehensive picture of the organization’s value-creating activities.

This new representation of strategy communicates to everyone in the organization what the organization is about: how it intends to create long-term value and where each individual can make a contribution to organizational objectives. Individuals are freed from narrow and restrictive job descriptions, a legacy of the scientific management movement of a century ago. They can now come to work each day energized about doing their job differently and better, helping to advance the organization’s success and realize their personal objectives.

New information, ideas, and actions, aligned with organizational objectives, emanate from the organization’s front lines and back offices. Employees become truly empowered by understanding what the organization wishes to accomplish and how they can contribute. Organizational units—business units, departments, support units, and shared services—understand where they fit within the overall strategy and how they can create value within their units and by working cooperatively with other units.

Communication by leaders is critical. Employees cannot follow if executives do not lead. Executives at our conferences regularly report that they could not overcommunicate the strategy; effective communication was critical for the success of their BSC implementations. One CEO told us that if he were to write a book describing his successful transformation of a large insurance company, he would definitely include a chapter on the Balanced Scorecard; it played an invaluable role in the turnaround. But he would devote five chapters to communication, because he spent most of his time communicating with business unit heads, frontline and back-office employees, and key suppliers such as insurance brokers and agencies.

Managers report that they must communicate seven times, in seven different ways. They regularly use multiple communication channels to get the message out: speeches, newsletters, brochures, bulletin boards, interactive town hall meetings, intranets, monthly reviews, training programs, and online educational courses.

Reinforce and Reward with Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation should reinforce the strategic message. The most successful Balanced Scorecard implementations have occurred when organizations skillfully melded intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. If the organization succeeds because of the efforts of its employees, it should share some of the increase in value with the employees who made it happen.

Quite a few Balanced Scorecard implementations have failed, however, when companies relied only on extrinsic motivation. They changed the compensation system to include nonfinancial measures—organized by customers, processes, and people—as well as traditional financial measures. But the new compensation system was more a checklist of measures, and not a reflection of a new strategy. Executives never communicated the rationale for the measures, nor did they embed the measures in a coherent strategic framework such as a Strategy Map containing linked strategic objectives and measures across the four Balanced Scorecard perspectives.

Companies use two principal tools to create extrinsic motivation. First, they align employees’ personal objectives and goals with the strategy; some have even created personal scorecards. Setting objectives for individuals, of course, is not new. Management by objectives (MBO) has been around for decades. But MBO is distinctly different from the kind of employee objectives established with the guidance of a Balanced Scorecard. The objectives in a traditional MBO system are established within the structure of the individual’s organizational unit, reinforcing narrow, functional thinking. In contrast, when employees, through communication, education, and training, come to understand the strategies of their unit and enterprise, they can develop personal objectives that are cross-functional, longer-term, and strategic. Annually, employees validate their personal strategic objectives with the help of their supervisors and human resources professionals. Several organizations have even encouraged employees to develop personal Balanced Scorecards, with each employee setting targets to improve a cost or revenue figure, boost performance with external or internal customers, improve a process or two that will deliver customer and financial value, and enhance a personal competency to drive process improvement.

The second source of extrinsic motivation is unleashed when companies link incentive compensation to targeted scorecard measures. To modify and align behavior as required by the strategy and as defined in the scorecard, an organization must reinforce change through incentive compensation. When Balanced Scorecard measures are linked to an incentive compensation program, managers see a significant increase in employees’ level of interest in the details of the strategy.

Incentive plans vary widely across organizations. The plans, however, generally have an individual component and a business unit and enterprise component. Plans that calculate awards only on business unit and enterprise performance signal the importance of teamwork and knowledge sharing, but they also may encourage individual shirking and free rider problems. Plans that reward only individual performance generate strong employee incentives to improve their personal performance measures, but they inhibit teamwork, knowledge sharing, and suggestions to improve performance outside the employee’s immediate accountability and control. Typical plans therefore include two or three kinds of awards: (1) an individual award based on achieving targets established annually for each employee’s personal objectives, (2) an award based on the employee’s business unit, along with, perhaps, (3) an award tier for divisional or enterprise performance.

We often are asked how to weight the measures in a Balanced Scorecard. Such a question may be a sign that the organization does not truly understand the Balanced Scorecard management system. It is using the BSC narrowly for extrinsic motivation, by modifying its compensation plan, but has bypassed the more important strategy-setting and communication aspect of the BSC, which creates intrinsically motivated employees. Nevertheless, linking the scorecard to compensation is the time (and the only time) when weights do have to be created so that a multidimensional BSC can be reduced to cash, a single dimension.

Organizations select weights based on the nature of their business and their short-term priorities. When there is little time between improvement in employees and processes and subsequent financial performance, the financial measures can be weighted heavily. Organizations that create value over longer periods of time through innovation, human capital development, and deployment of customer databases should weight these internal process and learning and growth metrics more heavily. If the company has a quality problem, then it can weight process improvement metrics heavily; if it has a customer loyalty problem, then it can weight customer satisfaction and retention more heavily. If the company’s strategy requires a rapid installation of new information technology or a major retraining of employees, then those measures can be weighted heavily during the year to highlight the importance of achieving the performance targets during the next twelve months. And if it has an immediate need for cost reduction, then measures related to process improvements and productivity will be highly weighted. Thus, although measures may stay relatively consistent from year to year, the relative weights applied to those measures in the annual compensation plan can vary based on short-term priorities.

We have learned, however, that paying bonuses when financial performance is poor is probably not a good idea even if customer, process, and employee performance are excellent. Financial performance may be disappointing in the short run because of external factors such as an economic or industry slowdown, unexpected changes in macroeconomic variables such as exchange rates, interest rates, and energy prices, or hypercompetition in the industry. Whatever the causes, bonuses must be paid in cash and such payments may not be desirable when the company is hemorrhaging cash during times of financial distress.

This consideration argues for setting a minimal financial hurdle before bonuses are paid. The hurdle might be measured by, say, achieving profits as a targeted percentage of sales, or a minimum return on capital, or achieving breakeven in an economic-value-added calculation. Once the financial hurdle has been exceeded, some portion of the excess is committed to a bonus pool, with actual bonuses based on performance of BSC metrics and a majority of weight on measures in the three nonfinancial perspectives.

Best-Practice Case: Unibanco

Unibanco, with more than $23 billion (USD) in total assets, is the fifthlargest bank in Brazil, and the third-largest in the private sector. Unibanco started its Balanced Scorecard project in 2000 by building a company scorecard and scorecards for its four major business units: insurance and pension, retail, wholesale, and asset (wealth) management.

During 2001, senior executives launched a communication campaign to inform all twenty-seven thousand employees about the new strategy and the method for managing it. Unibanco called on the Schurmann family of Brazil, famous for traveling the world in a sailboat, to give talks to two thousand managers at various bank locations on the topic “We’re all in the same boat,” emphasizing that each crew member must know the destination to contribute to the objective of the boat reaching it successfully.

Advertisements and articles about the Painel de Gestão (management panel) and the relevant indicators appeared on the corporate intranet portal and the internal TV network, as well as in the internal monthly magazine and in personal e-mails sent to every manager. The “successful sailing” campaign branded the scorecard concept for employees and made all the employees aware that their everyday actions affected the success of the company strategy.

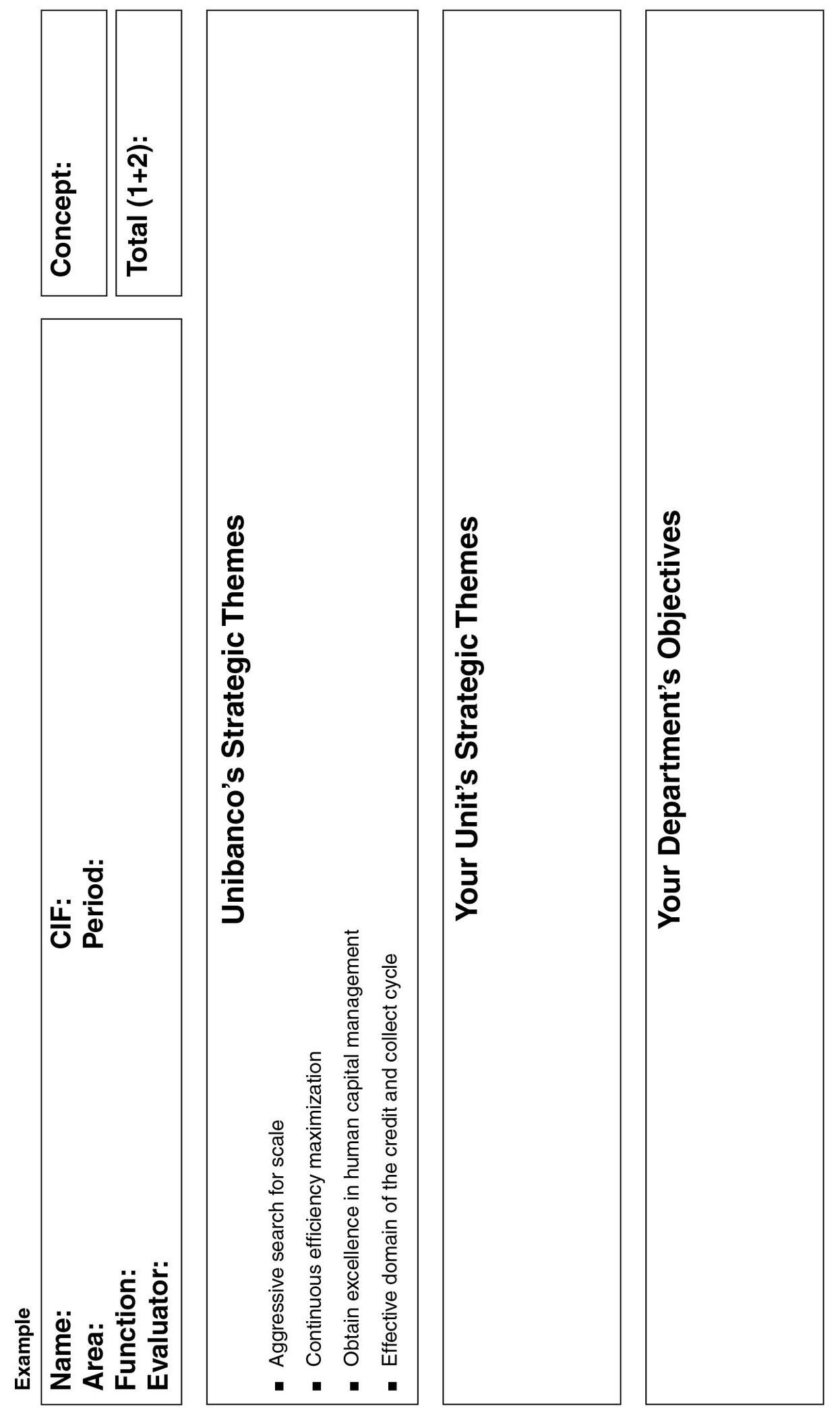

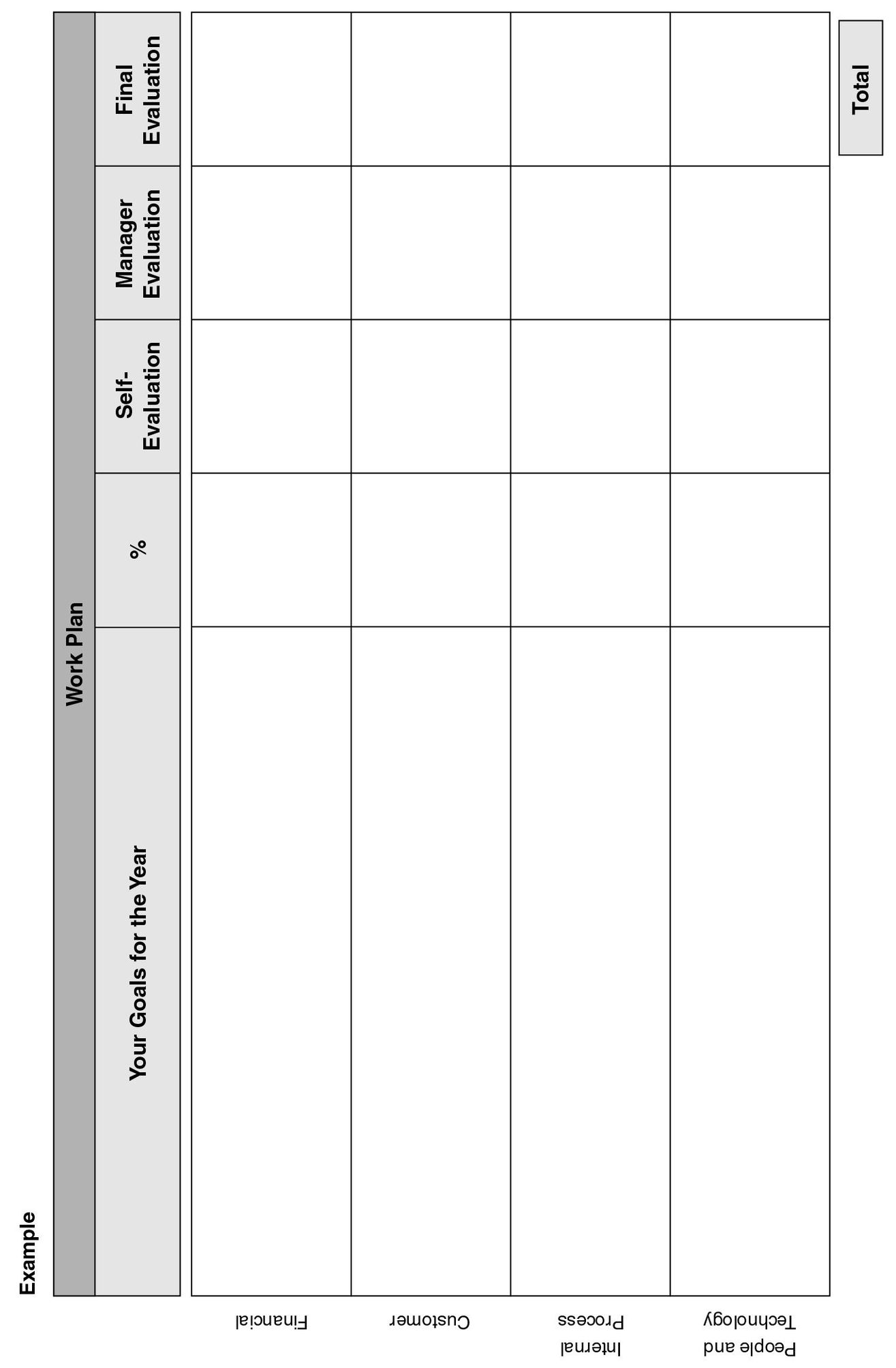

In 2002, Unibanco deployed extrinsic motivation by adapting an existing personnel management tool, the management agreement between each employee and his manager. The first page of the revised management agreement (Figure 10-3) described the unit’s and the bank’s strategic themes. Then employees, with their supervisors, created their personal management agreements (Figure 10-4), which would now be aligned with the unit’s and the bank’s strategic themes. The management agreement contained employee objectives in the four BSC perspectives, with each objective derived from one or more unit and corporate strategic themes.

For example, an employee in the marketing department, helping to create a campaign to stimulate new accounts, would have a financial objective related to the estimated lifetime value of new accounts acquired. An employee producing an output used by another bank unit would treat the value delivered to the other unit as a customer objective. For the learning and growth objective in the management agreement, the human resources group helped employees determine the competencies—knowledge, skills, and behavior—they required to reach the objectives in their three other management agreement perspectives.

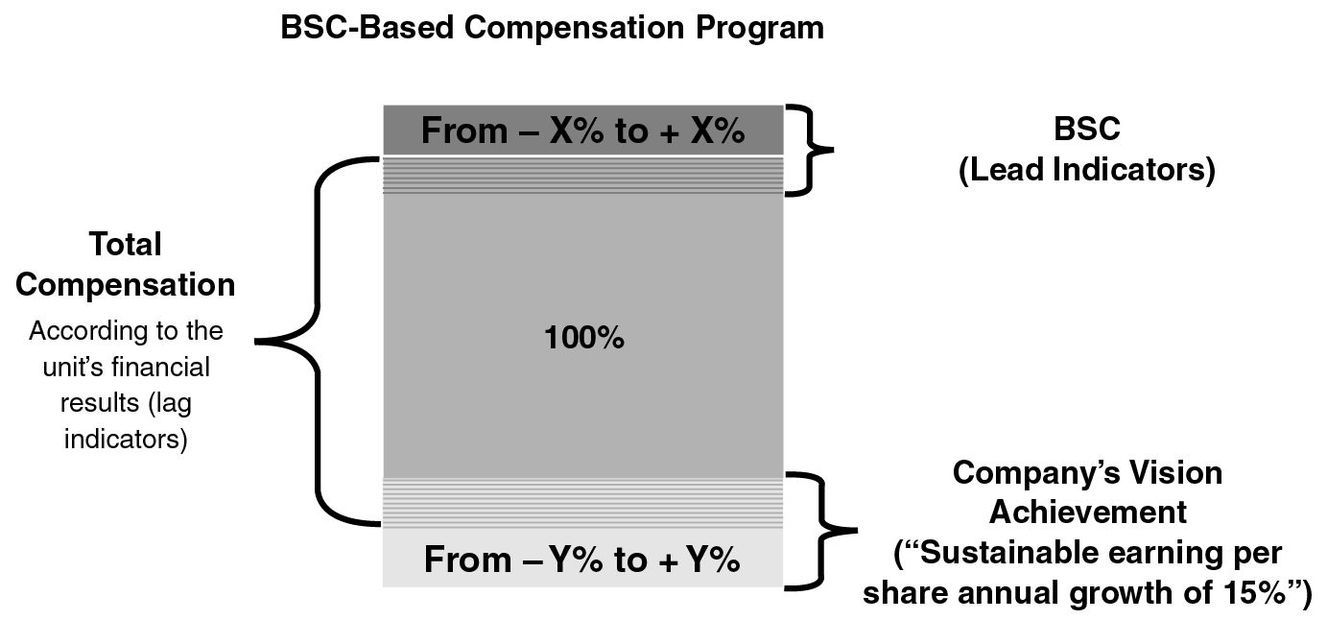

Unibanco deployed a second extrinsic motivation tool when it imbedded the management agreement in every employee’s recognition and bonus plan. Unibanco’s previous compensation program had assigned a total compensation pool to each unit based on the unit’s financial performance. The bank modified this program (see Figure 10-5) by adding two elements of variable pay. It added (or subtracted) a percentage to the compensation pool based on the leading (nonfinancial) indicators on the unit’s Balanced Scorecard; another percentage was added or subtracted based on the company’s performance. The company included a corporate bonus component so that employees would think about the total bank’s performance, and not just the performance of their decentralized unit.

Then in 2004, Unibanco re-energized intrinsic motivation by launching a new “2-10-20” communications campaign. The company set the following goals to achieve, by its eightieth anniversary year in 2006: R2 billion in income, R10 billion in equity, and a 20 percent return on equity. The communications program promoted the 2-10-20 slogan everywhere, including in elevator displays.

People were encouraged to tell the story of how their actions led to successful outcomes. Each monthly issue of the internal magazine selected the best stories to celebrate the individuals and teams that had achieved significant results on key performance indicators. Annually, Unibanco provided a presidential reward for initiatives that achieved breakthrough results for a strategic theme.

Figure 10-3 The Management Agreement at Unibanco

Figure 10-4 Personal Goal Setting at Unibanco

Figure 10-5 Unibanco: Employee Compensation System

From 1999 to 2004, Unibanco employees’ “comprehension of the company’s mission and vision” rose from 72 percent to 83 percent. Earnings per share increased from 5.57 in 1999 to 9.45 in 2004, with expectations of continued substantial increases in future years (to reach the 2-10-20 targets).

Develop Employee Competencies

One final stage is required if organizations are to align employees with strategy. Employees must develop the skills, knowledge, and behavior—which we call employee competencies—that enable them to make dramatic improvements in the critical processes that create value for customers and shareholders.

We have described in other work how to identify the strategic job families that have the greatest impact on the critical processes for strategy execution.6 Significant resources must be devoted to enhancing the employee competencies in the strategic job families. Beyond the strategic job families, employees also have personal objectives that they aspire to achieve. All employees should have accompanying personal development plans that will help them acquire the skills, knowledge, and behavior that make it feasible for them to achieve their personal objectives. In fact, the entire chain of strategy execution starts by equipping all employees with the required competencies to achieve their personal objectives, which link to process improvements, loyal and profitable customer relationships, and, eventually, superior financial performance.

Best-Practice Case: KeyCorp

Cleveland-based KeyCorp is one of the nation’s largest bank-based financial services companies, with assets of over $90 billion and more than nineteen thousand employees. The company provides investment management, retail and commercial banking, consumer finance, and investment banking products and services to individuals and companies throughout the United States and, for certain businesses, internationally.

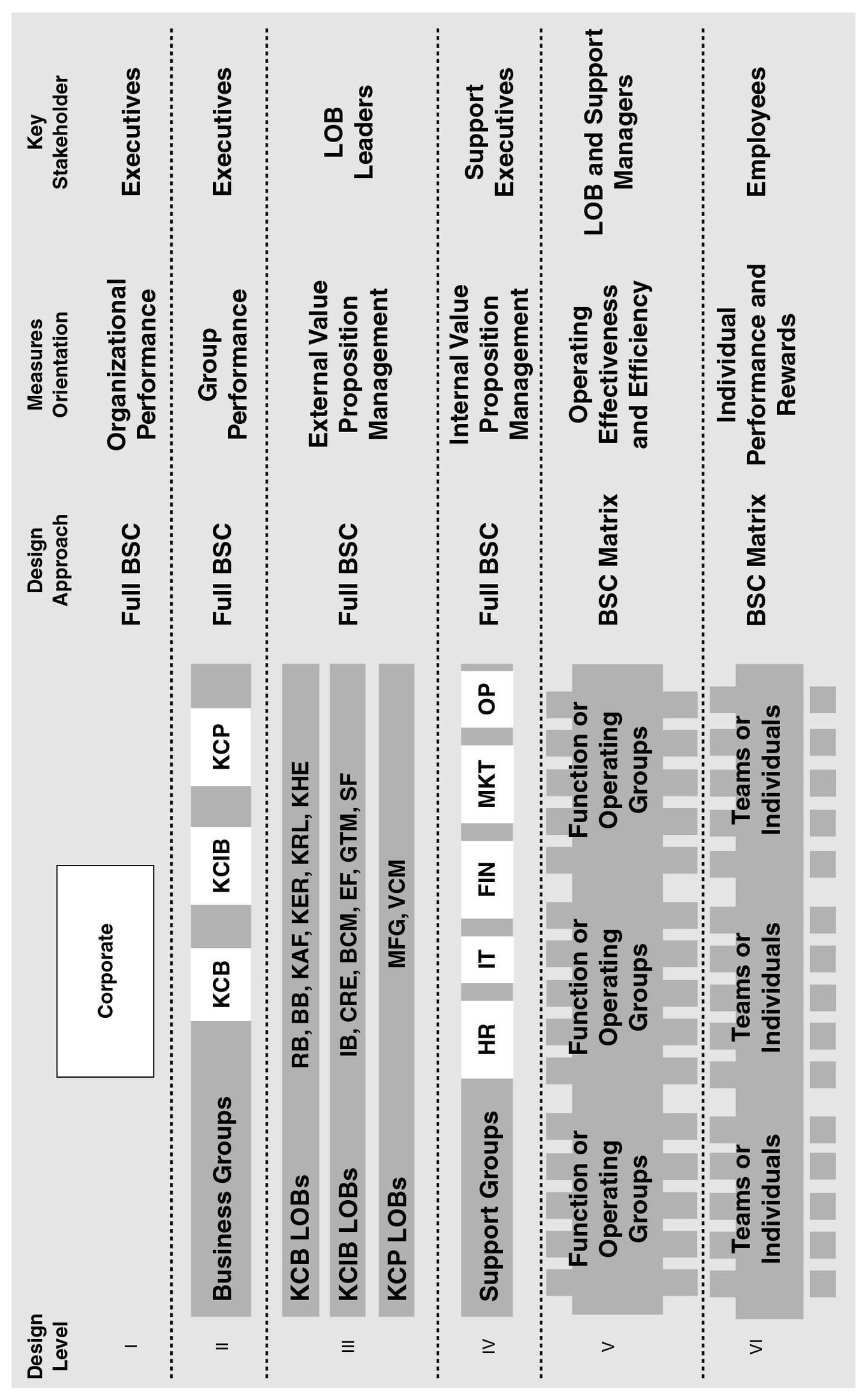

KeyCorp’s Balanced Scorecard program followed a classic cascading process (see Figure 10-6). In 2002, under the leadership of newly appointed CEO Henry Meyers, the company created a corporate Strategy Map and BSC containing strategic themes across the four perspectives: “enhance shareholder value (financial) by being the trusted adviser (customer) through excellent execution that brings the full power of KeyCorp’s capabilities to all client relationships (internal) and staffed by people proud to be at Key and who live the Key values (employee).”7

The BSC team, led by Michele Seyranian, EVP Strategic Planning, cascaded KeyCorp’s high-level corporate themes and objectives to scorecards in what, at the time, were its three major business groups: Key Consumer Banking (KCB), Key Corporate and Investment Banking (KCIB), and Key Capital Partners (KCP) (brokerage, investment banking, and asset management). These level II scorecards were then cascaded down to level III (the fifteen lines of business) and to level IV (five corporate support groups: human resources, information technology, finance, marketing, and operations). A further cascading brought strategic objectives to level V, functional or operating groups within each line of business. The project—cascading the Level I corporate scorecard down to Level V functional and operating group scorecards—was completed by the end of 2002.

The final cascading stage to employees, level VI, was accomplished by aligning individual performance objectives and rewards with Key’s strategic themes and objectives. A particular alignment challenge arose in KCIB, which had to integrate its traditional corporate banking business with a recently acquired investment banking business. The culture of the corporate bankers was quite different from that of the investment bankers, and yet individuals from both groups had to learn to work together to sell seamlessly to corporate clients.

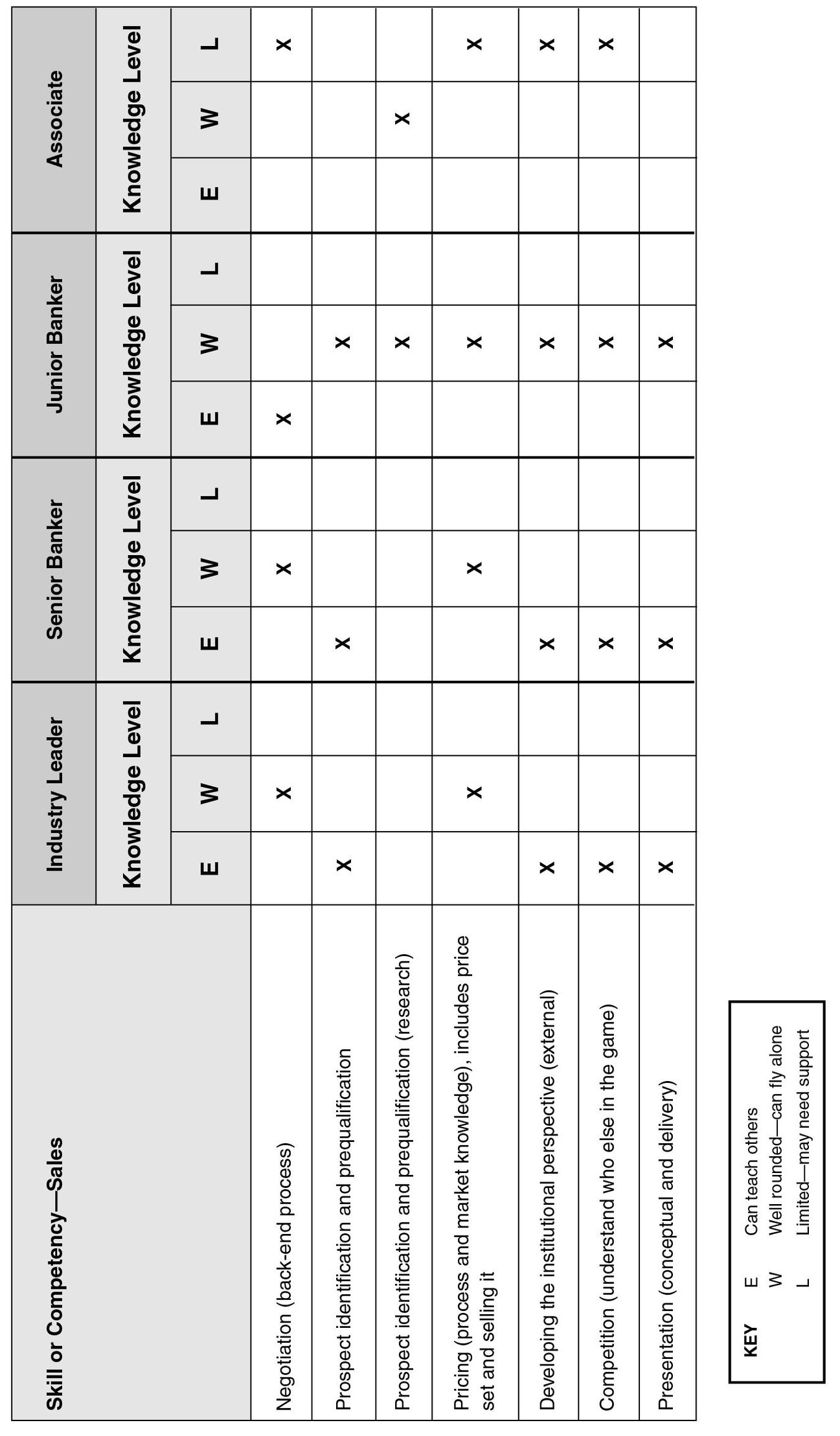

Figure 10-6 KeyCorp Cascades Corporate and Business Unit Objectives to Employees

Tom Bunn, KCIB President, partnered with Susan Brockett, HR Director for KCIB, to lead a project team to create focus, alignment, and accountability around the KCIB strategy. A critical component of the transformation was the identification and definition of those positions in the newly created KCIB organization that would have the greatest impact on outcomes. The team started by developing a detailed list of the skills and competencies required for each critical job position and the learning needs for each job to close gaps in foundational sales, client management, functional, product, and technology skills. For each position, the team identified the skill levels that were necessary for the employee to make an immediate impact with the new business model, which combined corporate and investment banking functions (see Figure 10-7).

For example, an industry leader and a senior banker needed to be expert—capable of teaching others—in prospect identification, competition assessment, presentation skills, and development of the institutional perspective. A junior banker, in contrast, needed to have working-level skills in these areas but needed expert skills in negotiations to be able to close deals that had been identified and sold by senior bankers and the industry leader.

The project team identified training courses that could bring all individuals up to the required skill levels for their positions. It tracked the enrollment and performance of employees in the various training courses that were offered. KeyCorp soon saw the results of linking its comprehensive competency development program to critical strategic objectives. Unlike earlier training initiatives, KeyCorp’s training courses had 100 percent attendance at every session. Employees responded with evaluations such as this one: “The course I just completed is immediately applicable to the work I am now doing . . . When is the next course on [skill xyz] being offered? . . . Finally, training that fits my job.”

Lesa Evans, Senior Vice President of Employee Development, led the effort to design the comprehensive competency development program. Line leaders actively participated throughout the needs assessment, program design, and alignment of the curriculum to individual development plans. For this effort Lesa was nominated for and received the Chairman’s Award for Outstanding Performance Contribution. When she accepted it, she was greeted with a standing ovation from the 150 top KeyCorp executives.

Since the formation of KCIB in 2002, and its focus of improving its banker’s skill sets to create a single point of coordinated contact for its clients, KCIB’s ROE has improved 28.8 percent (16.1 percent in 2005, up from 12.5 percent in 2002). The new business model is delivering results, as revenues have increased and margins have improved. In 2004 KCIB earned $486 million for the year, up nearly 36 percent from $358 million in 2003.

Figure 10-7 Example: Determining Knowledge Level at KeyCorp

ALIGNING PLANNING, OPERATIONS, AND CONTROL SYSTEMS

The final component of the alignment equation deals with management systems that guide planning, operations, and controls.8 These management systems assist managers as they clarify direction, allocate resources, guide actions, monitor results, and adjust direction as required. As shown in Figure 10-8, the planning, operations, and control activities complete the closed-loop, goal-seeking process that places organization strategy at the center. Our research into the approaches of successful organizations has identified several best management practices (noted in the figure and described next).

The Planning Process

The Strategy Map allows an organization to clarify the logic of its strategy. Strategic objectives for shareholders, customers, people, and processes are defined and linked to a set of cause-effect relationships. Beyond defining and describing the strategy, executives must plan the supply of resources to execute the strategy. Three management best practices for planning have been observed: initiative planning, integrated HR and IT planning, and budget linkage.

Initiative Planning

Initiatives—special projects with a finite life span—advance the strategy by accomplishing specific changes, creating strategic capabilities, improving processes, or otherwise enhancing organizational performance. Initiatives contribute to closing the gap between actual and targeted performance on a Balanced Scorecard measure. They also generate a stream of strategic benefits that supports future strategic investments.

Initiative planning involves two steps. The first, rationalization, entails the review and assessment of the current portfolio of initiatives, maintaining only those that directly support specific strategic performance needs. This step establishes what the organization would like to do. Second, managers periodically create a consolidated resource and implementation plan for the initiative portfolio that closes all identified performance gaps. This step addresses the practical constraints of step 1, answering the question, “How many of the rationalized initiatives can we afford?”

Figure 10-8 The Strategic Management Process

Best-Practice Case: The City of Brisbane

The City of Brisbane (Australia) has a rigorous approach to its initiative rationalization. By pinpointing the projects that align most closely with strategy, Brisbane is able to be rigorous about analyzing initiatives and understanding their relationships to strategic outcomes.

Each year, during the planning cycle, cross-functional teams (each with a broad set of capabilities) assess as many as four hundred initiatives to determine whether they fit the city’s strategy. This analysis is applied only to projects whose costs exceed a certain threshold beyond what an individual city department could fund from its own budget. The teams use an analytic method to score each project according to its strategic relevance, and then use these scores to set priorities among the many proposed and existing initiatives. Many initiatives, of course, don’t make the cut.

Individual teams use initiative-specific criteria in their assessment process. For example, for a proposed $10 million project to install filter beds in area creeks, team members looked at three key criteria, including “increased water quality” and “decreased noxious flora and fauna.” They then rated the criteria by their relative importance and the effect of the project in achieving the objective (“healthy rivers and bays”) and computed the scores. From these figures, members calculated the degree of fit for the project in achieving the desired outcome.

Using the BSC, executives map every funded initiative and activity aligned to the organization’s strategy, establishing an important link between high-level vision and operational activities.

Integrated HR/IT Planning

Intangible assets such as human capital and information capital take on value only in the context of strategy. Therefore, planning for human resources and information technology should be aligned with the strategic plan of the organization. The following three-step process aligns HR and IT plans to the organization’s strategy:

- Identify the intangible assets required to support the strategic internal processes on the organization’s Strategy Map.

- Assess the strategic readiness of these assets (how readily deployable the assets are in supporting organizational strategy).

- Establish measures and targets to track progress in closing any gaps between current readiness levels and what is needed to effectively execute the strategy.

Best-Practice Case: City of Brisbane (IT Planning Alignment)

The City of Brisbane sought to make strategic information available to all of its thousands of employees. It created a customized software program and data warehouse to showcase all scorecards, performance information, and the status of objectives and indicators.

By making available this detailed reporting information, the city enabled tight alignment between IT investments and the city’s strategic objectives. IT projects are closely mapped to strategy; those that don’t match must be reassessed. Brisbane’s IT switched its planning approach from culling (reactive) to preempting (proactive) by identifying line-of-sight links to the strategy. Its goal? To limit the number of IT projects and restrict them to only those that are strategic. Once projects pass strategic muster, the city identifies gaps between IT capability and strategy and determines how technology can be better used to reach strategic objectives.

Budget Linkage

Critics of traditional budgeting argue that it is beyond repair and must be abolished. Admittedly, the budgeting process of most organizations is slow, cumbersome, and expensive, and it hinders effective management during rapid change. But when the BSC is introduced into an organization, an opportunity arises to convert the budget process into a useful means of strategic resource allocation. The BSC makes it possible to transform this deeply ingrained process into one that contributes to both strategic outcomes and operational performance.

Best-Practice Case: Fulton County Schools

The Fulton County school system, based in Atlanta, begins its annual budgeting, planning, and strategy process with the BSC. With annual priorities clearly articulated in the BSC, school officials at Fulton can allocate funding to the most strategic programs. Central office departments refine their strategic plans based on annual priorities represented in the BSC and then develop their budgets.

At planning and budget review sessions with top school administrators, department leaders explain their plans for the upcoming year and justify their requested budgets. School principals, in turn, meet once a year with their area superintendents to propose their use of discretionary resources in alignment with their strategic plans. The public is invited to view budget documents and comment on budgetary decisions during two annual public hearings.

The BSC has helped Fulton County Schools increase its accountability to taxpayers. Using it to justify new projects has also helped boost the school system’s credibility in the business community, whose support is necessary if tax increases are needed for new educational initiatives. BSC data clearly shows which programs support the overall strategic mission—boosting overall academic performance—and which ones do not. The BSC thus helps the school board determine which programs to retain or eliminate.

The Operations Management Process

Having developed the plans, committed the resources, informed and aligned the organization with those plans, our best-practice companies typically rely on a variety of operational processes to execute the strategy. These processes tend to fall into three categories: (1) continuous improvement programs like total quality management, (2) initiative management programs that execute one-time change programs, and (3) programs for sharing best practices. Each of these creates value for the enterprise through alignment of program content with the strategy.

Process Improvement

Although more than a century old, quality management has enjoyed a revival in the past twenty-five years, thanks to the success of many Japanese companies. Today, the quality movement encompasses such programs as total quality management (TQM), the Baldrige National Quality Program, the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), and, most recently, six sigma. Reengineering, championed by Michael Hammer and James Champy in the 1990s, is a powerful approach to discontinuous process improvement.9 Activity-based management stimulates process improvement and management insight, starting from the organization’s cost model. Customer management—embodied in customer value management, customer relationship management, and customer life-cycle management—focuses the attention of managers and employees on operational improvements to yield better performance.

These various approaches to process improvement have helped many organizations achieve dramatic gains in the quality, cost, and cycle times of their manufacturing and service-delivery processes. Inevitably, many of the same organizations that adopt the BSC to implement their strategies need to integrate one or more of these management disciplines. But some organizations are confused about the relative roles of these programs and do not understand how to integrate them, especially if one is already in place.

The BSC can be effectively combined with one or more of these approaches to achieve advantages beyond what any one of them could deliver on its own. It imbues each with organization-wide legitimacy, giving it a strategic context and anchoring the program to the overall management system in a holistic way. The scorecard’s cause-and-effect links help highlight those process improvements and initiatives that each program identifies as having the greatest impact on the organization’s strategic success. As one quality expert remarked at one of our conferences, “six sigma teaches people how to fish; the Balanced Scorecard teaches them where to fish.”

Best-Practice Case: Siemens ICM

Siemens Information and Communications Mobile (ICM), the mobile communications unit of Siemens AG, has successfully combined the top-down strategic focus of the BSC with the bottom-up approach of six sigma. ICM combined the two approaches for two reasons: to reach all individuals in the organization, and to equip them with the means to close performance gaps.

ICM uses the BSC to identify strategic gaps in key cross-functional processes: idea to market, problem to solution, and order to cash. Six sigma is then used, at the project level, to drive out defects, wasted time, and non-value-added costs from these processes.

ICM believes that although six sigma may empower small teams to solve concrete problems, it is not by itself a strategic tool. Since integrating these approaches, ICM has seen a change in managers’ behavior; meetings are now highly interactive, and the discussions focus on how projects are being used to achieve strategic performance targets. Managers now have a forum in which to fight for their parts of the strategy.

Initiative Management

Initiative management involves monitoring the progress of all strategic initiatives, assessing their relevance in light of strategic changes, and ensuring their timely completion. Effective initiative management begins with clear accountability. A member of the executive team is usually identified as the initiative sponsor. This means that any issues that are blocking progress can be efficiently dealt with by an individual empowered to make changes. A program manager is appointed and becomes responsible for executing the initiative.

These programs can be simple, stand-alone projects, such as a training program, or complex, ongoing projects, like six sigma. The program manager requires a broad set of skills in project management, consulting, relationship management, and change management.

Best-Practice Case: Handleman

When the Handleman Company introduced its BSC program, executives saw the BSC’s potential as a strategy-coordinating and management tool throughout the company’s many different entities. Handleman created a center for performance management (CPM) to promote strategy execution as a core competency. To be most effective, this new organizational entity was given an overarching set of responsibilities—and the support of executives at the highest levels. Handleman uses initiative management to manage its portfolio of initiatives to ensure coverage of the entire strategy.

CPM devised a four-step initiative management process that it uses with the company’s executive team council.

- Gating: council members screen proposed initiatives to determine those meriting formal review.

- Presenting: Once proposals are approved for consideration, CPM presents them to the council for a final go/no go decision.

- Tracking progress: CPM follows a disciplined procedure to monitor initiatives’ progress.

- Tracking benefits: CPM follows a disciplined procedure to assess whether promised benefits are realized.

The tracking of progress and benefits is the core process for setting priorities and managing the ongoing strategic initiative portfolio. CPM conducts Balanced Scorecard review meetings to track, discuss, and take action on active, approved initiatives. Once an initiative is completed, the initiative owner conducts periodic lessons-learned analyses to determine whether the promised benefits are being delivered by the initiative and to capture strategic learning for future efforts.

Best-Practice Sharing

The strategic governance process should provide feedback that is used to test whether the strategy is working, and ultimately, whether it is indeed the best means of achieving the organization’s mission and vision. When BSC performance information is shared widely throughout the organization, people gain insights into the factors that contribute to performance. When the organization allows access to performance information, people can easily learn whether their strategy is working and which units, departments, and teams are doing a better job of achieving strategic outcomes.

Although the field of best-practices research is, by now, well developed, how to link specific best practices to strategic outcomes is less well understood. Traditional approaches to leveraging best practices typically are independent of strategy. Many organizations now use their BSC reporting capabilities to identify high-performing teams, departments, or units based on their ability to deliver strategic results. Organizations can then document how the high performance was achieved and disseminate this information broadly throughout the organization. In this way, they educate and train others about how to improve performance.

Best-Practice Case: Crown Castle International (CCI)

Crown Castle’s knowledge management system, CCI-Link, is a comprehensive database and library of the company’s best practices. This knowledge management tool, which taps BSC-based analysis, is key to centralizing and sharing performance information and best-practice knowledge throughout this global and highly decentralized company.

CCI uses the BSC to benchmark each of its forty district offices on strategic performance measures. Benchmarking helps executives discover which processes and practices work best across the firm, and it aids them in training people in other areas of the organization on these processes and practices so that they can meet the higher performance levels achieved elsewhere. A focus on internal best practices allows Crown Castle to incorporate the lessons learned and help integrate the strategy, scorecard, process improvement, and training activities throughout the organization.

Crown Castle’s knowledge management practice has contributed immensely to alignment and operational efficiencies—especially during a period of job cuts. CCI-Link’s core architecture is common across diverse geographies. Countries have common traditional functions listed, such as finance, assets, and human capital, but the content is largely local. A detailed analysis helps differentiate between geographic areas so that managers can understand the true basis for performance differences.

The Learning and Control Process

Arguably, the most important part of the closed-loop performance management process is the control process: the ability to detect deviations from target, to determine the cause of these deviations, and to take corrective action as required. When dealing with an organization’s strategy, this process is more about learning than about control.

A strategy is nothing more than a set of hypotheses about how the organization expects to achieve its desired results. The hypotheses should be tested continually, as part of a monthly review, analysis, and adjustment process. Two types of processes are found in our best-practice library: BSC reporting systems and strategy review meetings.

BSC Reporting Systems

Most early BSC reporting systems were based on off-the-shelf spreadsheet applications. Today, with more than twenty commercially available Balanced Scorecard software applications, BSC adopters increasingly are considering their automation options from the outset. And those that have already developed a spreadsheet-based reporting system are, by now, planning to migrate to a specialized BSC reporting tool.

What are the advantages of automation? Compared with manual systems, it is much easier to revise and aggregate data across scorecards, and data can be aggregated into “parent” scorecards, with far less time and effort. Analysis and decision making are thus more straightforward. That’s particularly important for organizations that have dozens of BSCs.

Best-Practice Case: Royal Norwegian Air Force

The Royal Norwegian Air Force uses an automated system called Cockpit to report the results of all its organization units’ scorecards. In addition to presenting data on most measures and initiatives, Cockpit includes executive assessments (interpretations).

This reporting system is based on an underlying enterprise resource planning platform and is accessible to all personnel. Updated information is reported through Cockpit every month, although a paper-based summary is also available. The agendas for strategy meetings are based on specific areas as reported and housed in the Cockpit application. Cockpit also supports management meetings.

Strategy Review Meetings

Just as the BSC is the centerpiece of the strategic management system, so is strategy itself the centerpiece of the new strategic management meeting. As advanced BSC users well understand, it’s no longer sufficient to say that the BSC is on the agenda; the BSC is the agenda.

These meetings should begin with an overall strategic performance review based on the Strategy Map and the relevant Balanced Scorecard(s). Even if data is not available for each measure (often the case early on), the management team should examine strategic performance in its totality. The owner of each objective leads the discussion about his or her objective (s) and the strategic theme(s) for which she is accountable.

It’s important that senior leaders create a supportive culture that encourages honest disclosure and does not punish negative results. Doing so fosters teamwork and motivates managers to reveal problems sooner, before they worsen. Below-target results should be seen as opportunities for improvement, as well as occasions to challenge the validity of the strategy—to understand whether and how it is actually working. Resources may need to be directed to underperforming areas, or executives may need to adjust targets that prove to be too aggressive.

At one organization, top strategic performers were reporting results in the red (under-target) zone. In fact, these units were outperforming other units that had not imposed equally aggressive targets on themselves. This situation arose in an organization that prized truthfulness and showed a great willingness to pursue stretch targets.

Best-Practice Case: Korea Telecommunications (KT)

Since early 2000, KT has used the Balanced Scorecard to drive the agenda of its quarterly executive meetings. Whereas agendas were once merely reports of financial results, today they are discussions of strategy in which participants refer to measurements within the four scorecard perspectives. The heads of KT’s twenty-four offices and business groups gather to discuss the performance of the previous quarter, along with overall performance and strategy. At the fourth-quarter meeting, executives evaluate the year’s overall strategic performance and plan strategies for the next year.

In addition to ensuring a timely flow and transparency of performance evaluation data, the BSC also profoundly affects the way executives track performance and manage strategy execution. The BSC serves as an organizing framework for discussion and analysis. For example, at one strategy review meeting, division heads identified early on the potentially explosive demands created by a new transmission technology, a result of BSC-related performance monitoring. Thanks to the BSC, management was prepared to quickly readjust the network capacity target to meet the new demands and was able to capture a greater share of this emerging market.

SUMMARY

Balanced Scorecard Hall of Fame companies have shown that strategy can be executed successfully. By allowing us to document their management practices, they have shown that the successful execution of strategy requires the successful alignment of four components: the strategy, the organization, the employees, and the management systems. Underlying this is the guiding hand of executive leadership. Each of these alignment components is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for success. Taken together, however, they provide a recipe around which a successful management process can be developed (see Figure 10-9).

Chapters 1–9 of this book describe the organization alignment process. This chapter provides a high-level overview of the processes for aligning employees and systems with the strategy. We believe that, taken together—along with our related work on Strategy Maps, Balanced Scorecards, strategy-focused organizations, and the office of strategy management—these processes constitute the foundation for a new science of strategy management.

Strategy execution is not a matter of luck. It is the result of conscious attention, combining both leadership and management processes to describe and measure the strategy, to align internal and external organizational units with the strategy, to align employees with the strategy through intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and targeted competency development programs, and, finally, to align existing management processes, reports, and review meetings with the execution, monitoring, and adapting of the strategy.

Figure 10-9 Management Best Practices Underlying alignment

NOTES

W. Edwards Deming, Quality, Productivity, and Competitive Position (Cambridge, MA: Center for Advanced Engineering Study, MIT, 1982), 101–104.

M. E. Porter, “What Is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review (November–December 1996).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, “The Office of Strategy Management,” Harvard Business Review (October 2005).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, “Measuring the Strategic Readiness of Intangible Assets,” Harvard Business Review (February 2004): 52–63; see Chapter 8, “Human Capital Readiness” in Kaplan and Norton, Strategy Maps, 225–243.

KeyCorp quote.

The content of this section is drawn from “Govern to Make Strategy a Continual Process,” Balanced Scorecard Report (January–February 2005).

M. Hammer and J. Champy, Re-engineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution (New York: Harper Business, 1993).