CHAPTER FIVE

ALIGNING SUPPORT FUNCTIONS

CHAPTERS 3 AND 4 SHOW HOW ENTERPRISES create shareholder value by aligning their business units with the corporate strategy. But organizations also create value by aligning their support units with the business unit strategy. Consider the approach advocated by Larry Brady, president of FMC Corporation:

I doubt that many companies can respond crisply to the question, “How does staff provide competitive advantage?” . . . We have just started to ask our staff departments to explain to us whether they are offering low cost or differentiated services. If they are offering neither, we should probably outsource the function.1

Support or shared-service units, such as human resources, finance, purchasing, and legal, have their origin in the nineteenth-century functional organization described in Chapter 2. The units contain employees who have specialized knowledge and expertise that can be productively deployed throughout the organization for tasks such as designing compensation and promotion systems, operating information systems, conducting international treasury operations, and managing regulatory and litigation matters. To achieve critical mass, support groups are typically centralized and, in the aggregate, incur operating expenses of between 10 and 30 percent of sales.

Senior executives have struggled for decades with the question of how to monitor and evaluate their support groups to ensure that they produce benefits in excess of their costs. Organizations such as The Hackett Group provide benchmarking information that compares the company’s spending on its support services to that of similar organizations. But such benchmarking is not really useful unless the organization’s goal is to spend the least amount possible on its support units and to not use these units as a source of competitive advantage.

The output of support groups—such as expert advice, a trained, motivated employee, a report, the design and operation of a key process, or a partnering relationship with a business unit—is often intangible. It is difficult to quantify these outputs when organizations attempt to evaluate a unit’s effectiveness and efficiency. The traditional management control literature refers to support units as “discretionary expense centers,” to contrast them with standard cost centers, where budgeted expenses can be linked, via tight causal mechanisms, to the production of standard products and services.2

Support groups are generally staffed with expert specialists whose culture is quite different from that of managers in line operating units. Consequently, support groups frequently become isolated from the line organization; executives of business units accuse them of living in headquarters-based functional silos and being incapable of responding to local operating needs. In two surveys we conducted, respondents reported that two-thirds of human resources and information technology organizations were not aligned with business unit and enterprise strategies. Correcting this misalignment and transforming the focus of support units—to one of meeting the needs of their internal customers—provide opportunities for substantial increases in shareholder value.

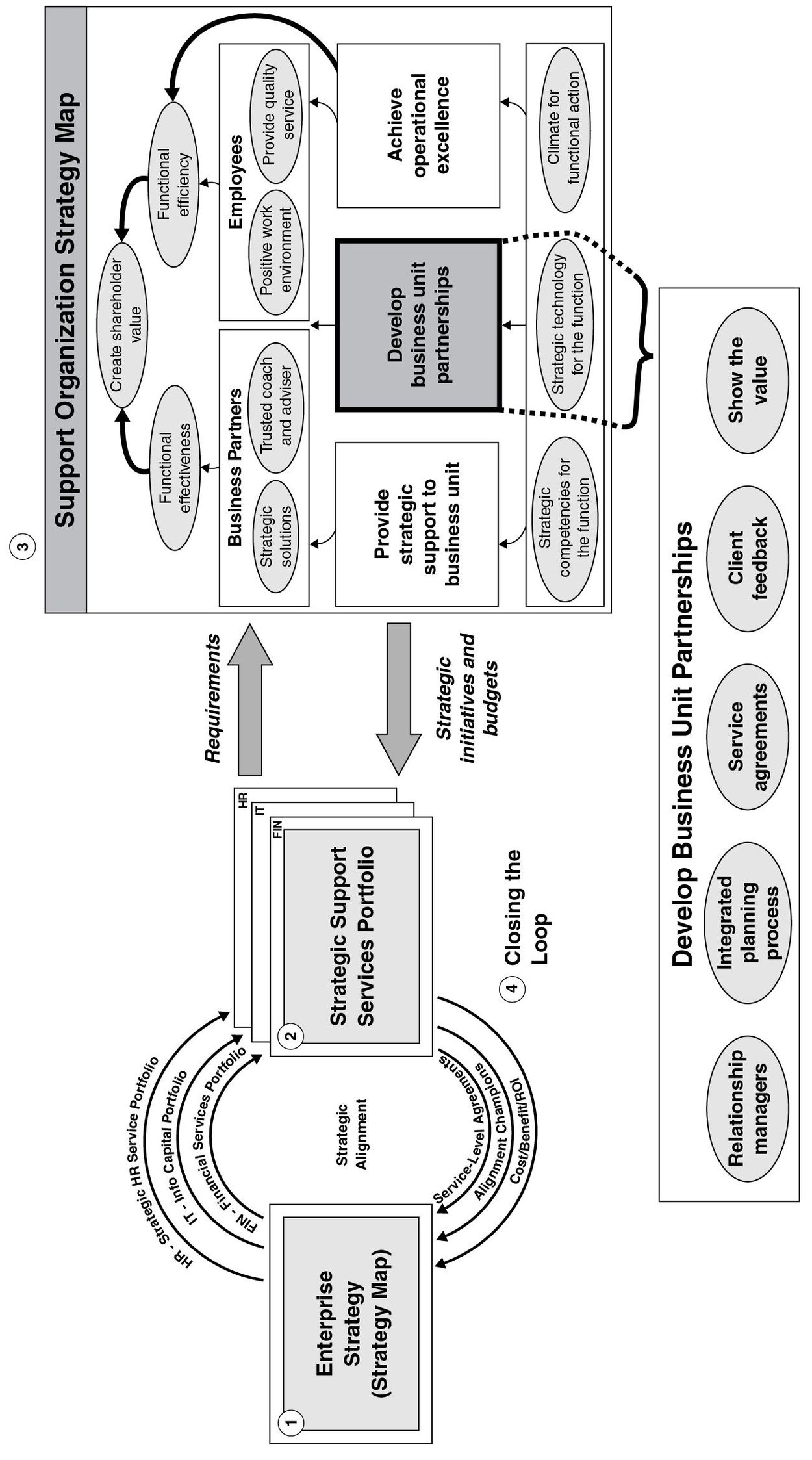

SUPPORT UNIT PROCESSES

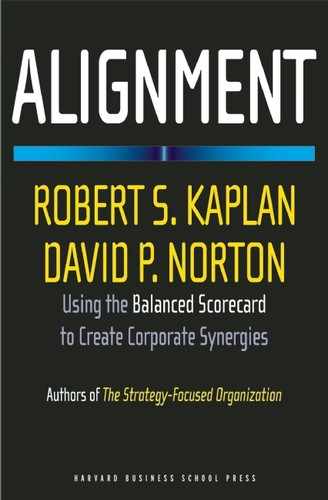

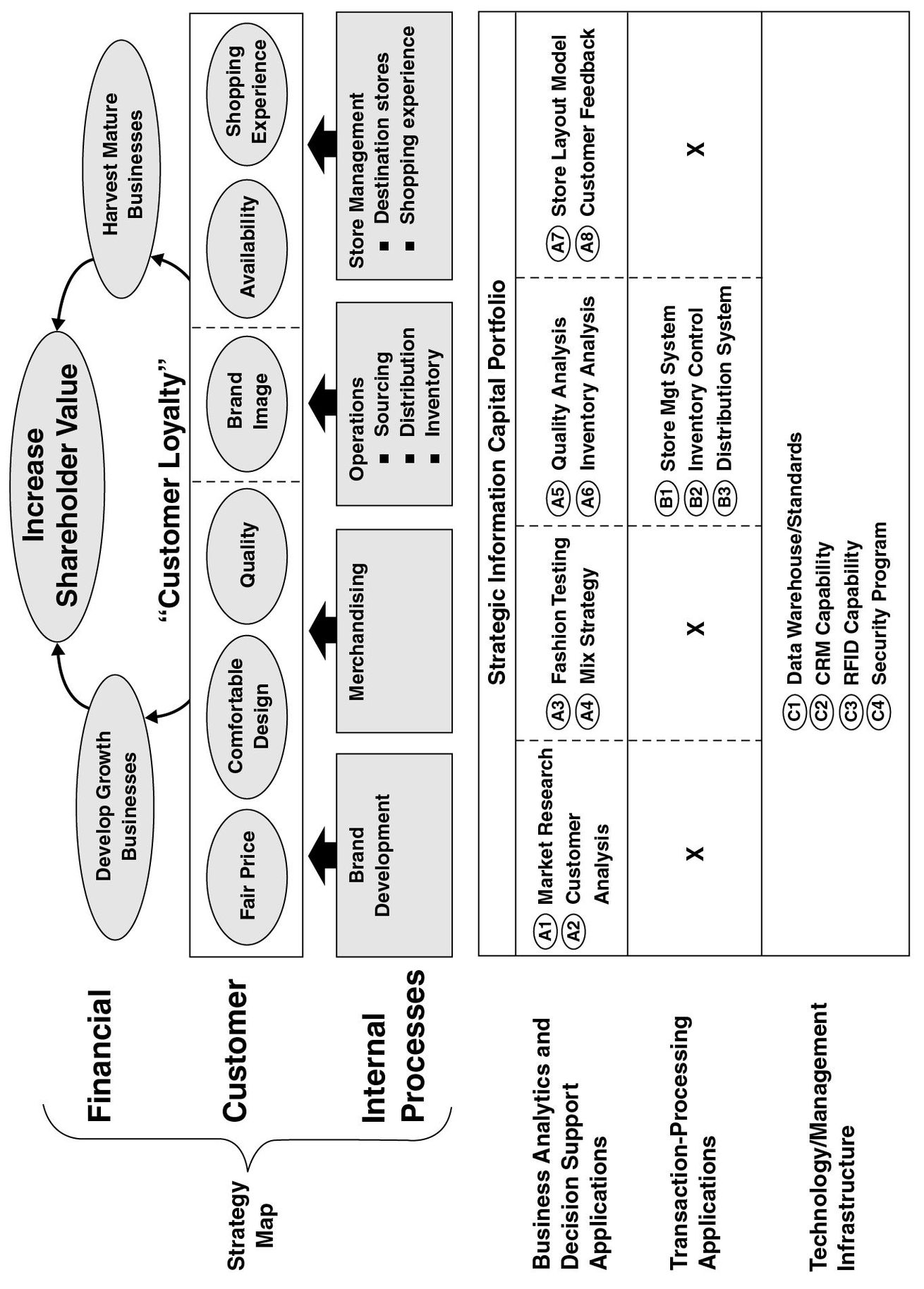

Support units can follow a systematic set of processes to create value through alignment (see Figure 5-1). First, they align their strategies with business unit and corporate strategies by determining the set of strategic services to be offered. The process starts with a clear understanding of enterprise and business unit strategies, as revealed by line organization Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards. Each support function then determines how it can help business units and the enterprise achieve their strategic objectives. For example, as illustrated in Figure 5-1, the human resources, information technology, and finance organizations identify a portfolio of strategic services that will have the greatest impact on the successful implementation of strategy.

Figure 5-1 Aligning Support Units with Entreprise Strategy

Second, support units align their internal organizations so that they can execute the strategy. They develop strategic plans that describe how they will acquire, develop, and deliver their strategic services to operating units. The plan becomes the foundation for the support units’ Strategy Maps, Balanced Scorecards, strategic initiatives, and budgets.

Finally, support units close the loop by assessing the performance of their functional initiatives using techniques such as service-level agreements, internal customer feedback, customer ratings, and internal audits.

As a specific example of this process, Canon, USA—a leading manufacturer and distributor of cameras, copiers, and professional optical products—conducts an annual strategy discussion forum at which business units and support units coordinate their strategies for the upcoming year. Business units start by presenting their strategies to the support units and explaining how support units can contribute to their success. Support unit executives review their past performance and propose their objectives, targets, and initiatives for the future. Line and support unit executives then conduct an active dialogue, culminating in approved support unit functional plans, including Strategy Maps, Balanced Scorecard measures, targets, and approved initiatives. These forums are held during the budget process, enabling the approved resource levels for support units and their strategic initiatives to be incorporated into budget decisions.

SUPPORT UNIT STRATEGIES

Given the quotation from Larry Brady at the beginning of this chapter, what kinds of strategies make the most sense for support units? In principle, support units can create competitive advantage by excelling at any of the strategy archetypes used by business units: low cost, product leadership, or complete customer solutions. Undoubtedly, some of a support unit’s activities should be performed at the lowest possible cost. These would be routine operational tasks such as payroll processing, benefits administration, and computer network maintenance. Such routine activities are necessary for the enterprise to function, but performing them in a world-class manner, other than at low cost, doesn’t provide the organization with differentiation for competitive advantage.

Also, support units that attempt to follow a strategy based solely on low-cost delivery of all their services run a high likelihood of becoming outsourced. Internal groups are not likely to sustain a cost advantage for routine processes over an external outsourcing company. The latter often has advantages from scale economies and the option of producing and delivering services from low-cost regions of the world.

Product leadership is also a difficult strategy to sustain in a service business. New capabilities can be quickly imitated by others. Although product leadership remains a potential strategic option, no organization that we have worked with has asked its service functions to excel at innovation. Support units, in practice, invariably opt for a customer solutions or customer intimacy strategy. They strive to be operationally excellent at delivering basic services at low cost and high reliability, but they also identify a few critical services that they can excel at and that contribute to the differentiation and strategy of the business units they serve.

The customer intimacy or solutions strategy requires that support units build partnerships with their internal customers. This, in turn, leads to requirements for employee competencies in relationship management and for a culture of collaboration and customer focus that is quite new for support units that previously existed in centralized functional silos. Making this transformation from functional specialist to trusted adviser and business partner becomes the critical capability for a support unit’s new strategy.

PORTFOLIO OF STRATEGIC SERVICES

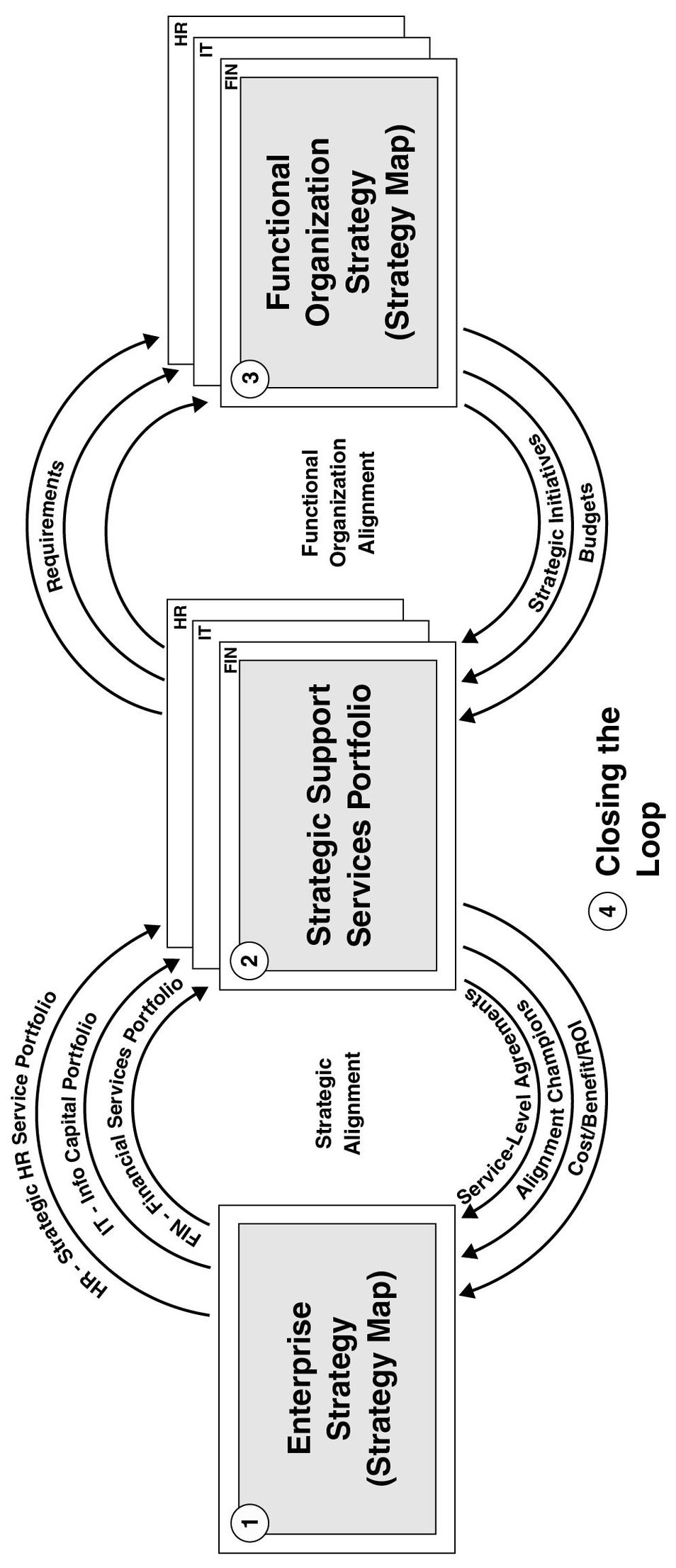

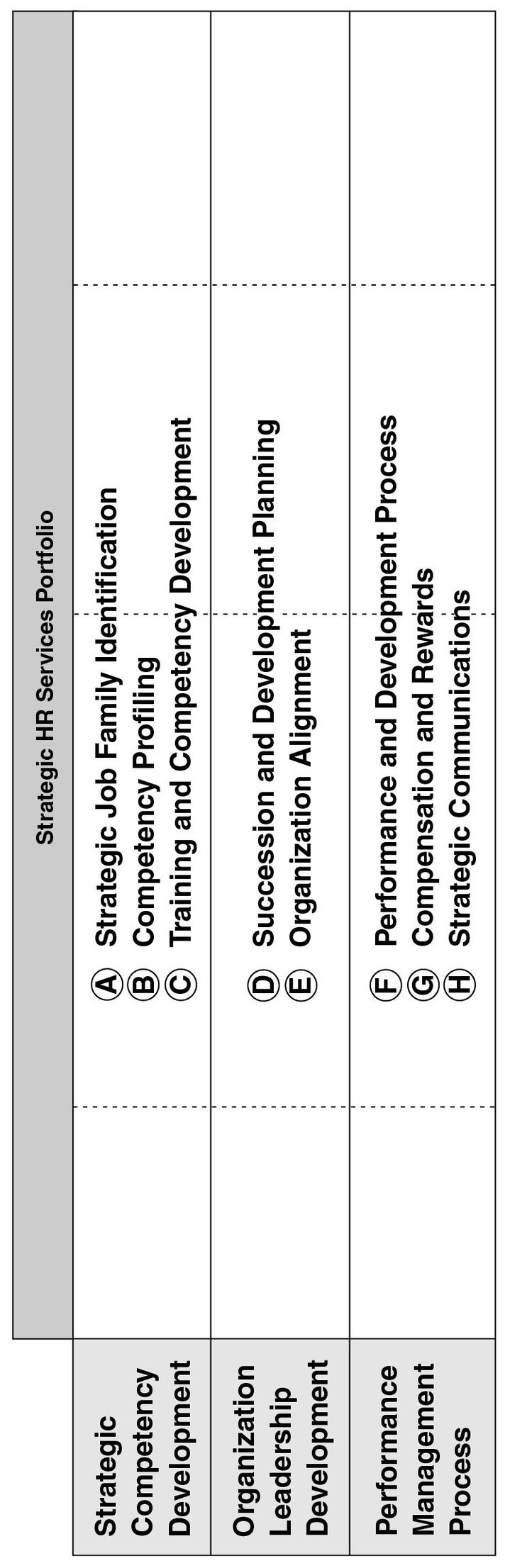

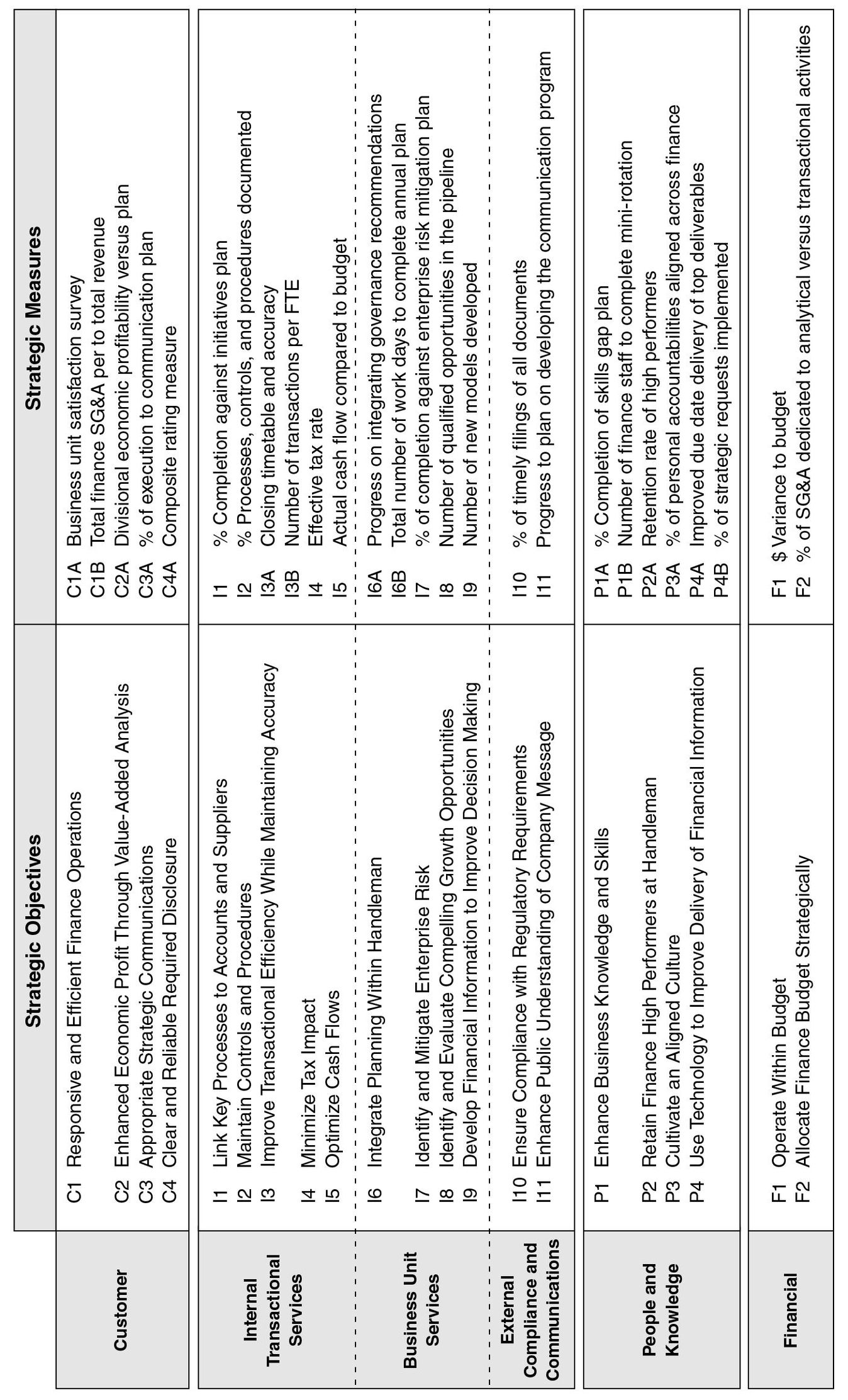

Support units enhance business unit and corporate strategies through the portfolio of services they offer (see Figure 5-2). Each support organization develops a customized set of potential strategic programs. A typical strategic services portfolio contains ten to twenty initiatives. We illustrate the process of developing the strategic services portfolio with three important support units: human resources, information technology, and finance.

Human Resources Portfolio of Strategic Services

Our experience of working with several dozen human resources groups has indicated that the HR strategic services portfolio usually has three components:

- Strategic competency development programs: These programs identify and develop personal competencies that are important to the success of the organization. The programs include identifying strategic job families, developing competency profiles for these families, analyzing the gaps between job requirements and existing competencies, and developing the training programs for employees to close the gaps.

Figure 5-2 A Portfolio of Strategic Support Services Form the Bridge Berween Entreprise and Funtional Strategy

- Organization and leadership development: These programs develop leaders, promote teamwork, foster organization synergy, and enhance the climate and values of the organization. The initiatives that can be included in this theme include developing the leadership competency model, conducting leadership development programs, succession planning, planning the rotation and development of key employees, developing culture and values, sharing best practices, and communicating strategy internally to all employees.

- Performance management process: These programs define, motivate, appraise, and reward the performance of individuals and teams. In particular the programs include helping to set performance goals for individuals and teams, conducting appraisals of individual and team performance, aligning employees’ incentive and reward systems with strategic objectives, and facilitating change management.

We illustrate how companies can develop their HR strategic services portfolio by using a case study from Handleman Company.

CASE STUDY: THE HANDLEMAN CORPORATION

The Handleman Corporation, with sales of $1.3 billion and more than 2,300 employees, operates as the music category manager and distributor for several leading retailers such as Wal-Mart and Best Buy. The music industry presents a range of business challenges, including technological change, piracy, customer concentration, and declining markets. Under the leadership of Chairman and CEO Steve Strome, Handleman adopted the Balanced Scorecard as the framework to clarify and execute its strategy.

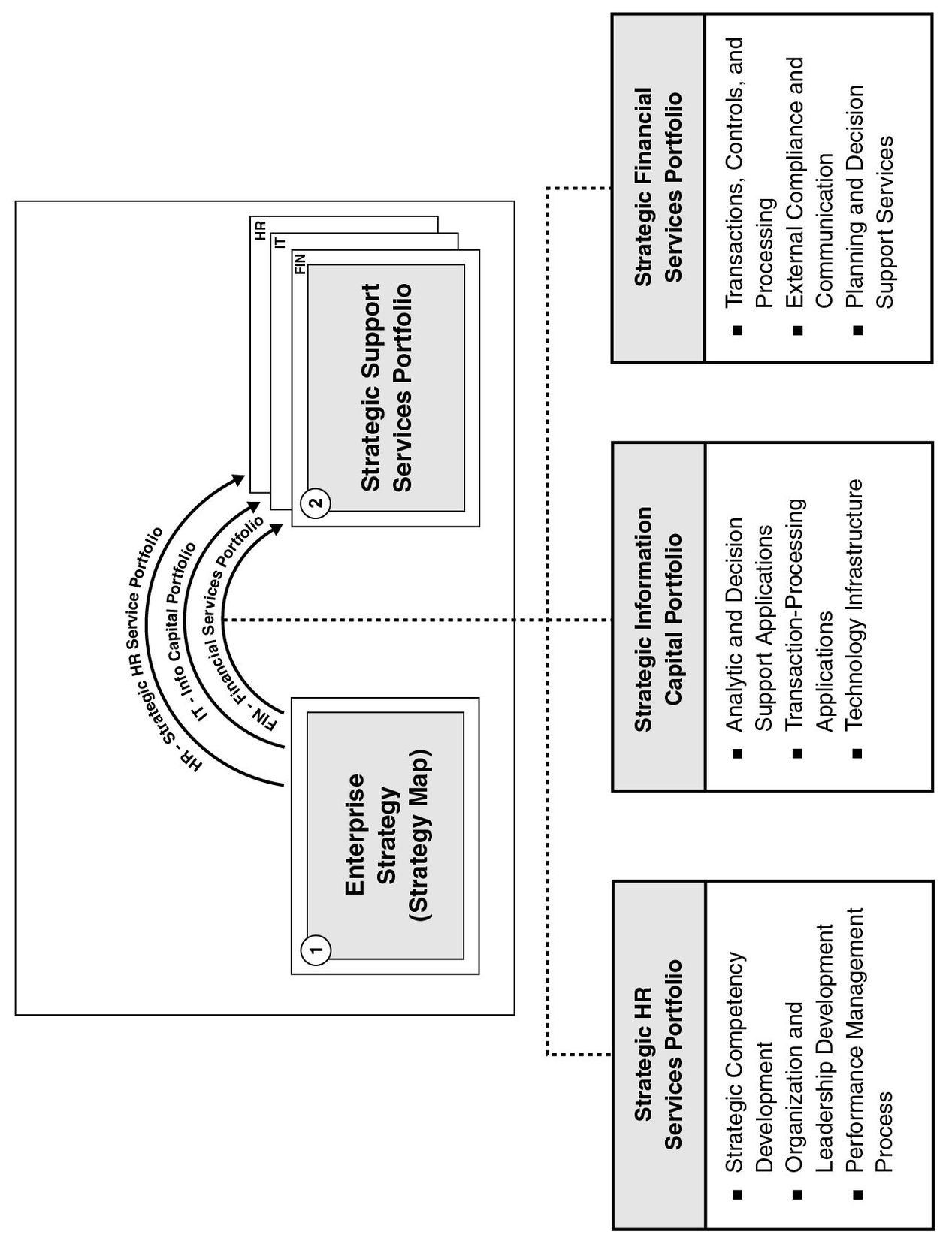

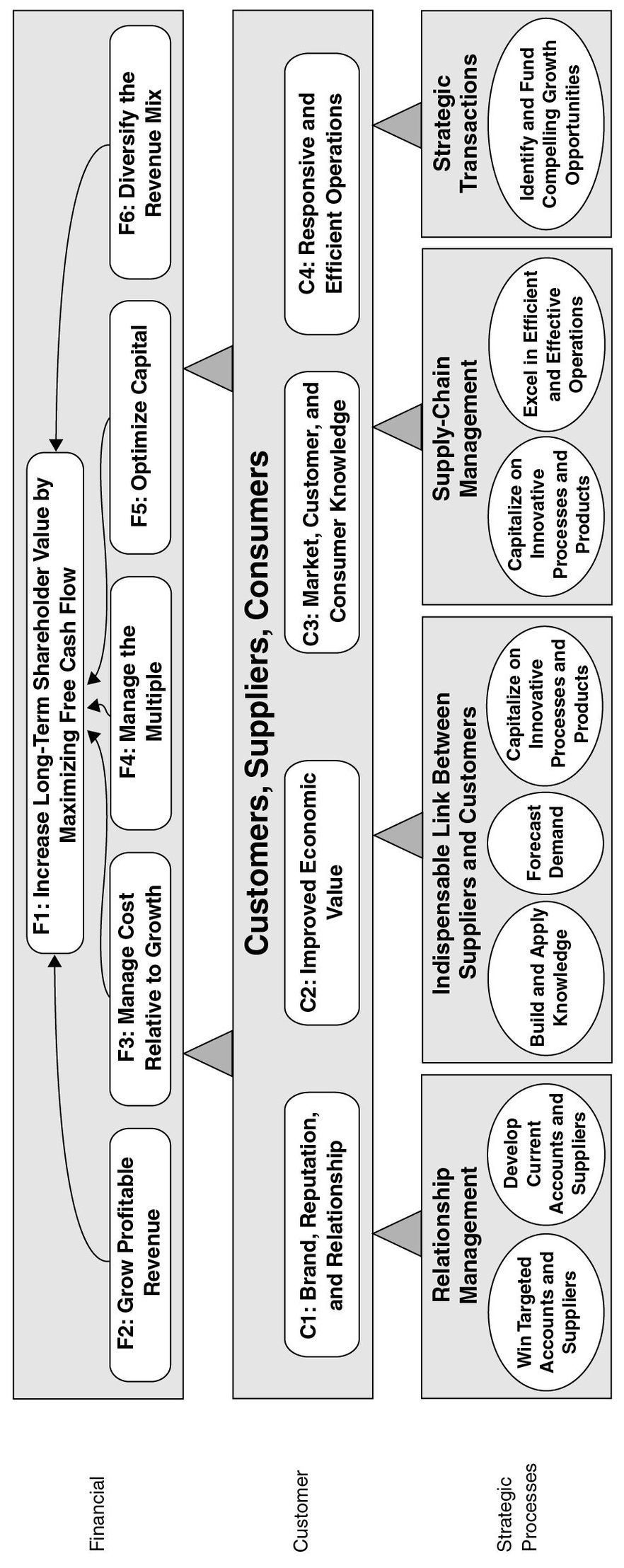

The upper part of Figure 5-3 shows the Handleman corporate Strategy Map (excluding the learning and growth perspective). A key process is applying specialized knowledge of consumer demands to become the indispensable link between the artists and labels (which provide the music) and retailers (which sell the music to consumers). Excelling at the critical internal processes of relationship management and supply-chain management would enable Handleman to deliver higher-quality service than merchants could do for themselves. And it would use strategic transactions to diversify into businesses having growth opportunities that leverage Handleman’s core capabilities and business expertise. Handleman cascaded its corporate Strategy Map to three geographic divisions—the United States, Canada, and U.K.—and to three shared-service units: human resources, information technology, and finance.

Figure 5-3 Strategic HR Services Portfolio at Handleman

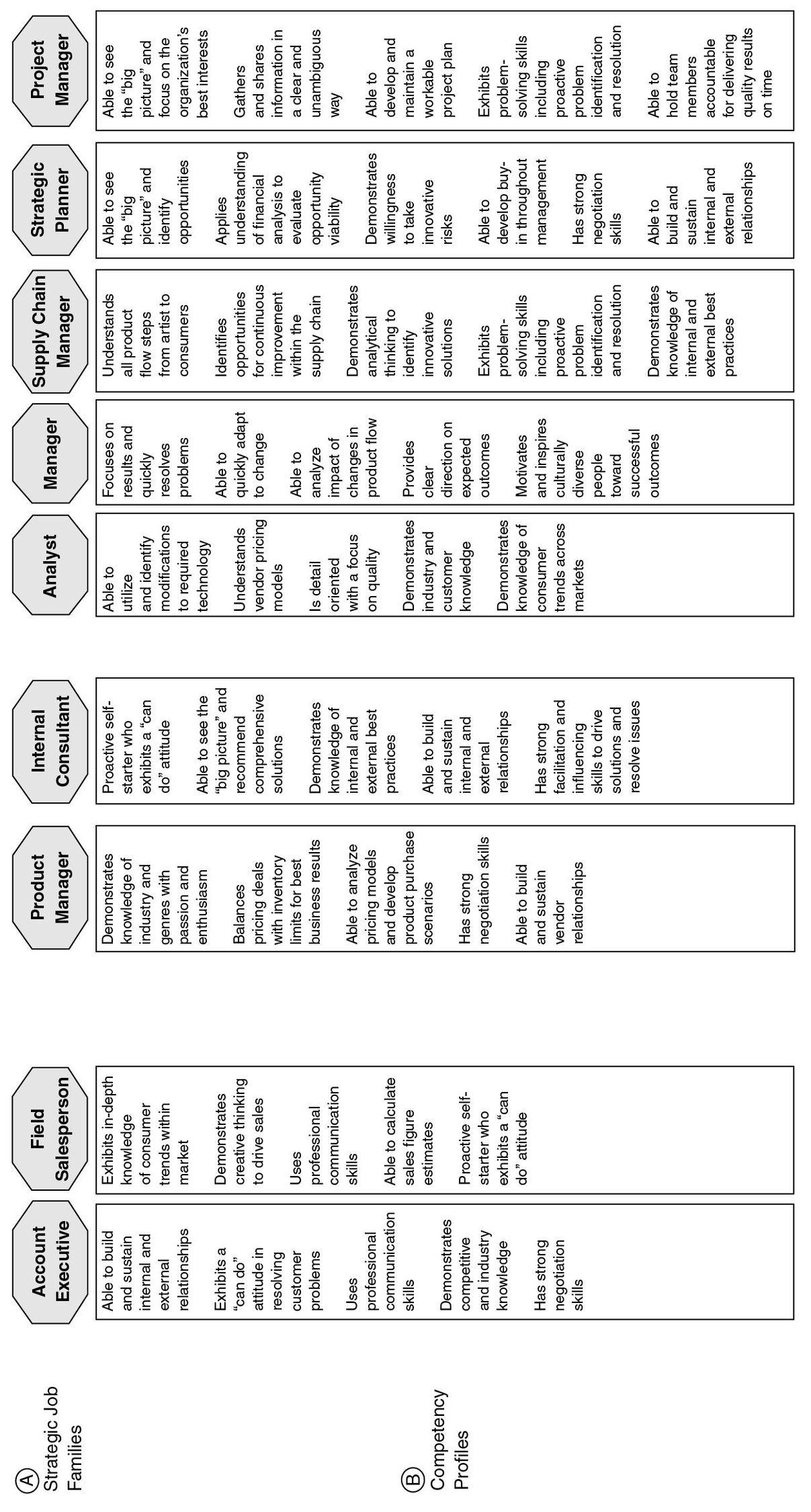

The lower half of Figure 5-3 shows how Handleman’s human resources organization developed strategic initiatives to support the corporate strategy. Starting with initiative A in Figure 5-3, HR executives worked with their line counterparts to identify the one or two job families that would create the greatest impact on each of the four corporate strategic themes. This process produced the nine strategic job families shown in the lower panel of Figure 5-4. In the aggregate, the total number of staff in these nine job families represented fewer than 10 percent of the 2,300-person workforce, allowing the HR organization to focus its staff development efforts on the critical strategic personnel.

For each strategic job family shown in Figure 5-4, an HR executive interviewed key employees and managers to identify the core competencies that were necessary for staffers to be successful in their positions (initiative B in the lower panel of Figure 5-3). The lower columns in Figure 5-4 summarize the competency profiles for each job family. For example, an account executive must have good industry knowledge and must excel at relationship management, communications, and negotiations. A product manager must master technical competencies, such as pricing, product purchase, and inventory management, as well as interpersonal competencies, such as negotiations and vendor relationships. The competency profiles, coupled with an assessment of employees currently in each job family, provided a framework for identifying gaps within individuals and across the organization.

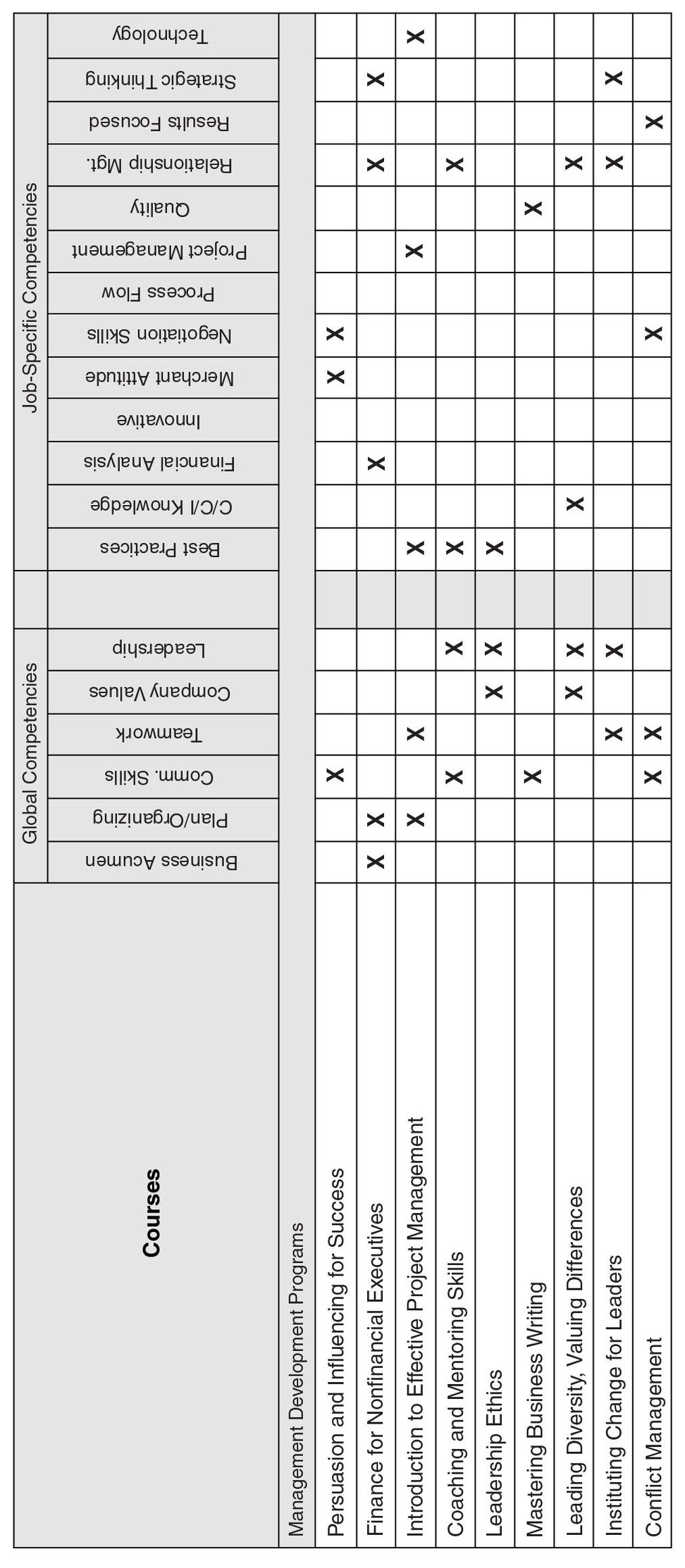

For initiative C in Figure 5-3, the training organization worked with the competency profiles to generate a consolidated list of training courses to close skill gaps in the strategic job families. It identified six global core competencies (see the column headings in Figure 5-5) that were common to all jobs: business acumen, planning and organizing, communications skills, teamwork, company values, and leadership skills. It also identified thirteen competencies that were specific to individual jobs: best practices; consumer, customer, and industry knowledge; financial analysis; innovation; merchant attitude; negotiation skills; process flow; project management; quality orientation; relationship management; a focus on results; strategic thinking; and technology knowledge.

The training organization then launched a series of nine management development programs to help employees obtain and strengthen the specific competencies required for their positions (see the row headings in Figure 5-5). In this way, training programs were directly linked to the strategic requirements of the organization, and the training budget and resources were focused on areas with the greatest return on investment.

The human resources organization, along with the Center for Performance Management (the balanced scorecard group) also led the delivery of the remaining initiatives shown in the bottom panel of Figure 5-3:

Initiative D, succession and development planning: Identify and cultivate high-growth individuals and prepare succession plans for each key job.

Initiative E, organization alignment: Facilitate the design and cascading of scorecards at all levels of the organization.

Initiative F, performance and development process: Help supervisors and employees develop personal objectives, scorecards, development plans, and performance reviews linked to the strategy.

Initiative G, compensation and rewards: Develop new programs to reward top performers and motivate employees to achieve strategic financial and nonfinancial objectives.

Initiative H, strategic communications: Communicate and educate the organization about the strategy through a broad range of channels, such as off-site forums, newsletters, management meetings, and training programs.

Handlemen, after three years of using the Balanced Scorecard, was named to Crain’s magazine list “Best Places to Work in Southeast Michigan in 2003” and included in “Metropolitan Detroit’s 101 Best and Brightest Companies to Work For” over four consecutive years. Handleman was also named the National Association of Retail Merchants Wholesaler of the Year for three consecutive years. This award recognizes Handleman’s outstanding achievements and continuing key role as an integral part of the music industry supply chain.

Information Technology Portfolio of Shared Services

The continued evolution and emergence of information technology offers every organization the opportunity for achieving performance breakthroughs and competitive advantage by effective alignment of this resource with corporate and business unit strategies.3 Those who don’t take a leadership position with IT run the risk that their competitors will. At the very least, an organization must be prepared to be a fast follower with respect to developing and deploying new IT capabilities.

Figure 5-4 Strategic Job Families and Competency Profiles at Handleman

Figure 5-5 Aligning Training Programs Core Competencies Required by the Strategy at Handleman

Every organization must identify and deliver the portfolio of information technology initiatives required to execute its strategy. The information technology portfolio, like its HR counterpart, typically has three components:

- Business analytics and decision support: applications that promote analysis, interpretation, and sharing of information or knowledge

- Transaction processing: systems that automate the basic repetitive events of the organization

- Infrastructure: the shared technology and management expertise required to enable effective delivery and use of information capital

Figure 5-6 illustrates the strategic portfolio approach at Sport-Man, Inc. (SMI). The top half of the figure shows a high-level image of the SMI Strategy Map, and the bottom half shows the company’s portfolio of strategic applications. Because the retail industry is transaction intensive, significant operational economies can be achieved through effective automation of transaction systems.

Wal-Mart’s rise to become the world’s largest retailer came in part from redefining and restructuring the supply chain that linked customer point-of-sale purchases to supplier replenishment. SMI has identified three transaction-processing applications as strategic. Application B1 is a store management system that automates the point-of-sale information; application B2 is an inventory control system that ensures that SMI is always in stock on its core merchandise; and application B3 is a distribution system that provides rapid replenishment of store inventory from regional distribution centers.

Because of the data intensity generated by these transactions, retail organizations make effective use of business analytic and decision support applications to understand consumer behavior and quickly adapt to it. SMI has identified eight such applications to support each theme of its overall strategy. For example, two applications that model and track customer behavior support the “brand development” theme. The market research application (A1) analyzes various market segmentation and value proposition alternatives, and the customer analysis application (A2) looks at customer profitability, cross-purchasing, and the annual purchasing cycle.

Figure 5-6 Strategic Information Capital at Sport-Man,Inc.

The ability to develop these transaction and analytic applications is based on the existence of a sound underlying infrastructure. More than one-half of the typical IT budget is invested in such infrastructure.4 SMI has identified four infrastructure applications: C1, a data warehouse to support the analytic and decision support programs; C2, a customer relationship management (CRM) platform to support store-level management; C3, an investment in radio-frequency identification (RFID) micro-chip technology for supply-chain management; and C4, a data-center security upgrade.

As with the HR portfolio, the IT portfolio typically includes ten to twenty specific applications to support the enterprise strategy, plus additional initiatives to support strategies specific to each business unit. These initiatives must then be converted into a plan that defines how the applications will be developed and how their development will be managed.

Finance Portfolio of Strategic Services

The finance function has specific statutory and operating responsibilities for the corporation. These responsibilities include financial transaction management, such as accounts receivable, accounts payable, and payroll; regulatory reporting, including investor reporting, managing relationships with internal and external auditors, and board reporting; and managerial reporting, such as monthly financials and budget variance reports.

These responsibilities are necessary for all organizations to perform. But if the finance department does not attempt to define a value-creating strategy, the operational and statutory responsibilities will dominate its agenda. A finance department, while continuing to serve in its operational and statutory roles, can add value by building strategic partnerships with managers in the line organization. An example of a strategic support service is helping a senior line manager understand reports on customer and product-line profitability and working with the line manager to develop action plans that transform unprofitable products and customer relationships into profitable ones. An enterprise strategic service would be to incorporate cross-business initiatives and programs into the periodic budgeting and planning process.

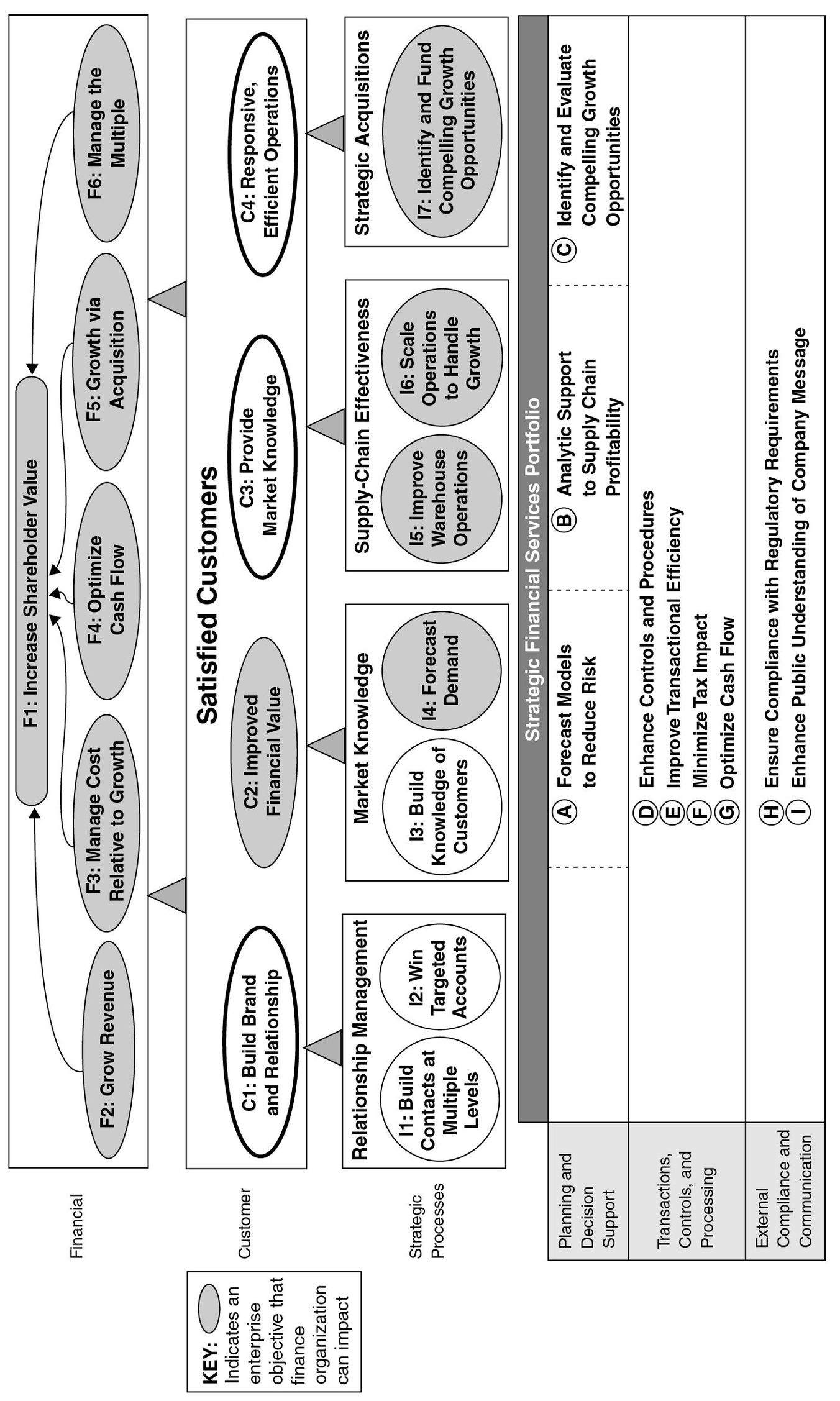

In Figure 5-2, we identified three components of a typical finance portfolio of strategic services:

- Transaction controls and processing: improvements in the structure and effectiveness of transaction systems, such as working capital management and risk analytics that facilitate business units’ asset productivity and risk-management strategies

- External compliance and communication: ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements and external communication, and ensuring that external reports and disclosures adequately reflect the company’s strategy

- Planning and decision support: analytics, consulting, and systems that improve the management of strategy across the organization

Figure 5-7 presents an example of the financial services portfolio development at Retail, Inc., a disguised organization that is structurally similar to our earlier case at Handleman. The top half of the figure shows a partial Strategy Map, clearly defining financial objectives, customer objectives, and four internal process themes. The finance organization, in a workshop with line executives, defined how its services could add value to the strategy. These objectives are shaded on the Strategy Map.

The strategic financial services portfolio is found in the bottom panel of the figure. The planning and decision support section of the portfolio contains three initiatives: A, a statistical model that processes historical data to improve forecast accuracy; B, activity-based costing analytics that calculate supplier and product-line profitability; and C, sophisticated financial planning software that supports the company’s merger and acquisition process. The remaining initiatives are more like infrastructure and are not linked to specific Strategy Map processes.

Four strategic initiatives support transactions, controls, and processing: D, improving controls; E, transaction processing efficiency; F, tax management; and G, cash flow optimization. The external compliance and communication section of the portfolio has H, an initiative for compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley, and I, an initiative to better communicate the company message to investors, intended to impact financial objective F6, “manage the multiple.” These nine initiatives constitute the portfolio of strategic services that will be managed and delivered by the finance organization.

ALIGNING THE SUPPORT ORGANIZATION

Once the strategic services for the support unit have been established, the unit must develop its strategy to deliver the promised services. This strategy, in turn, must be translated into a Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard that communicate the strategy to all support unit employees and help to monitor the performance of the support unit in delivering its strategic objectives.

A support unit, like a business unit, has a mission, customers, services, and employees. Some support units, such as the information technology departments of financial service organizations, have budgets that would place them on the Fortune 1000 list of largest companies. But support departments differ from business units in a couple of ways. Support units do not exist to make a profit; their purpose is to help business units in the line organization generate revenues and make profits. Also, the support unit’s customers are almost always internal, not external; the customers are the internal business units and their employees, who use or benefit from the services provided by the support unit.

Figure 5-7 Strategic Financial Services Portfolio at Retail, Inc.

When constructing a support unit Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, it is useful to think of the support unit as a “business within a business.” At the highest level, the support unit should have the same overarching goal as the enterprise—some measure of shareholder value (or its equivalent in nonprofits). It is essential that all the employees in the organization, whether in line units or support units, stay focused on the ultimate measure of success if they are to function as part of the corporate team.

The financial perspective of a support unit’s Strategy Map is divided into two components: efficiency and effectiveness. Support unit efficiency deals with traditional issues such as the cost of services delivered and adherence to budget. Support unit effectiveness describes the impact that the support unit has on the enterprise strategy. Sometimes referred to as a “linkage scorecard,” the effectiveness objectives should define the specific objectives and measures in the enterprise scorecard that the support unit directly impacts.

For example, an HR organization, through leadership development programs, might improve the enterprise’s ability to grow through acquisition. “Successful growth through acquisition” would appear on HR’s linkage scorecard. Even though HR does not have direct control over this objective—and, in addition, success might require the efforts of other departments—the HR organization is measured (and rewarded, in part) based on such linkage scorecard objectives. This ensures that the support unit always remembers and pursues the ultimate reason that it exists—to enhance enterprise and business unit strategies.

We have observed that some support units build their Strategy Maps as if they were nonprofit organizations, with the customer perspective on top, and the financial perspective—focusing on efficiency, productivity, and resource management—as a subsidiary perspective. Although we are sympathetic to this representation, most of the support units we have observed want to be thought of as contributing to value creation within their enterprises and therefore deliberately include some enterprise-level financial objectives at the top level of their Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards. They want to drive enterprise value creation, not just serve as a captive internal support function.

The support unit generally has two classes of customers: (1) the business unit managers to whom they provide services directly, and (2) the employees or external constituents who are beneficiaries and recipients of the services. Its typical customer intimacy or total customer solutions strategy calls for building business partnerships with its customers. Every support unit should understand its customers’ strategy and use its functional expertise to create and deliver solutions that contribute to its customers’ success.

The internal process perspective of a support unit scorecard has three themes. The first theme focuses on the function’s operational excellence, which will drive the efficiency objective of the financial perspective. Key measures for this theme include cost per transaction, quality, and response time.

The second theme deals with how the function manages the relationship with its internal customers. Service companies, such as IBM, Accenture, and EDS, devote considerable time to defining the processes and skills required for effective relationship management. This is the heart of their account-development strategies. Internal support staff should be no different; they, too, are service companies. They should make a similar investment in defining a client management process. Techniques such as a designated relationship manager, integrated planning, service agreements, and customer reviews have all proven effective.

The third theme deals with strategic support of the business. This theme drives the effectiveness component of the strategy, providing customers with new capabilities that enhance their strategies. The structure of this theme varies from function to function. The architecture mirrors the categories and the specific requirements found in the strategic functional services portfolio discussed earlier.

The learning and growth perspective reflects the specific needs of the functional staff for training, technology, and a supportive work climate.

In summary, the support unit strategy must be aligned with enterprise and business unit strategies. The strategic services portfolio (recall Figure 5-1) defines how the support function aligns its objectives with those of the line organization. This link should be clearly reflected in the customer perspective of the support unit scorecard. Periodic customer reviews should measure the progress being made in delivering the initiatives in the strategic services portfolio. The internal process perspective of the scorecard defines the way in which strategic support will be provided to the business unit.

We now demonstrate how to apply this general architecture to the development of Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards for the human resources, information technology, and finance functions.

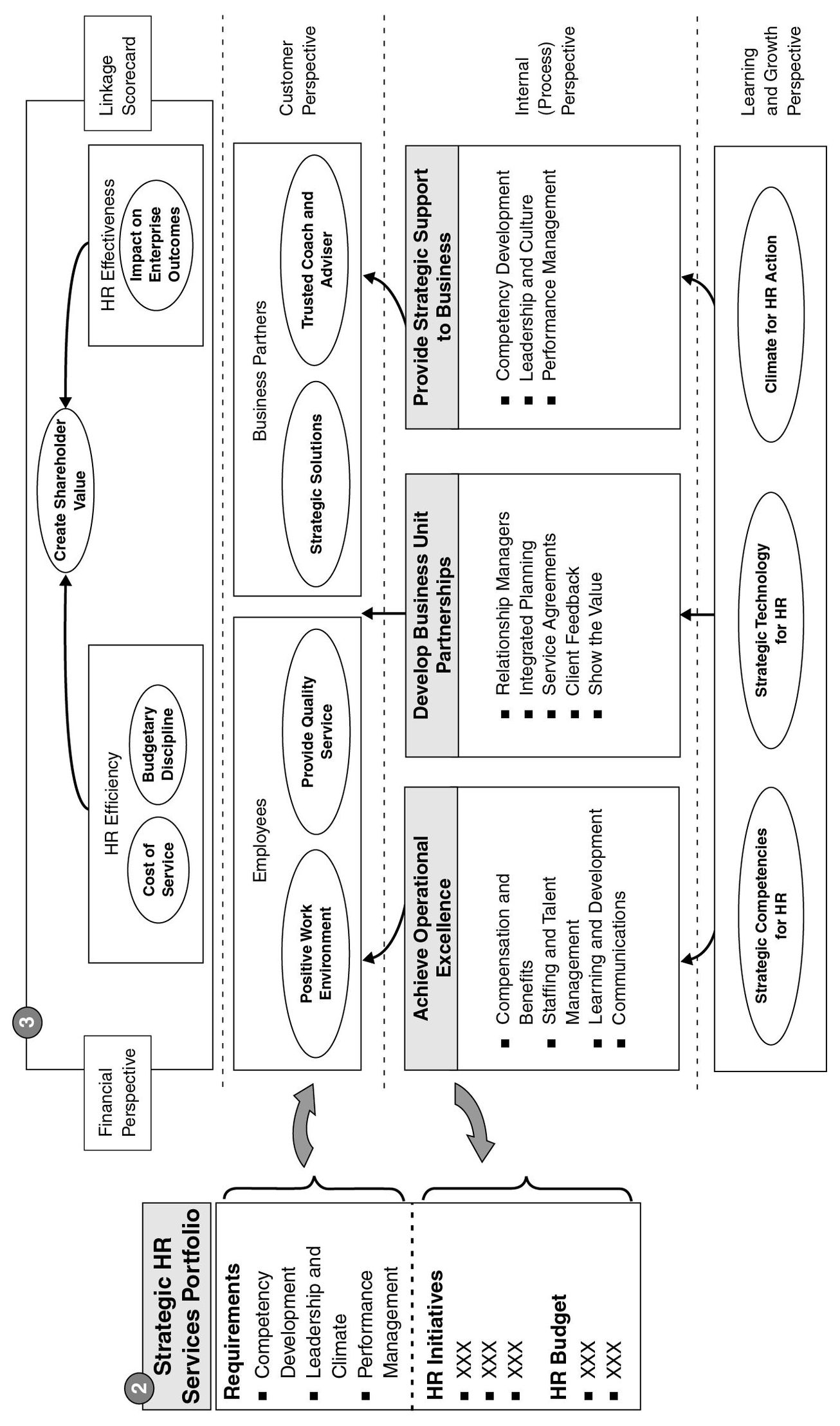

Aligning the HR Organization

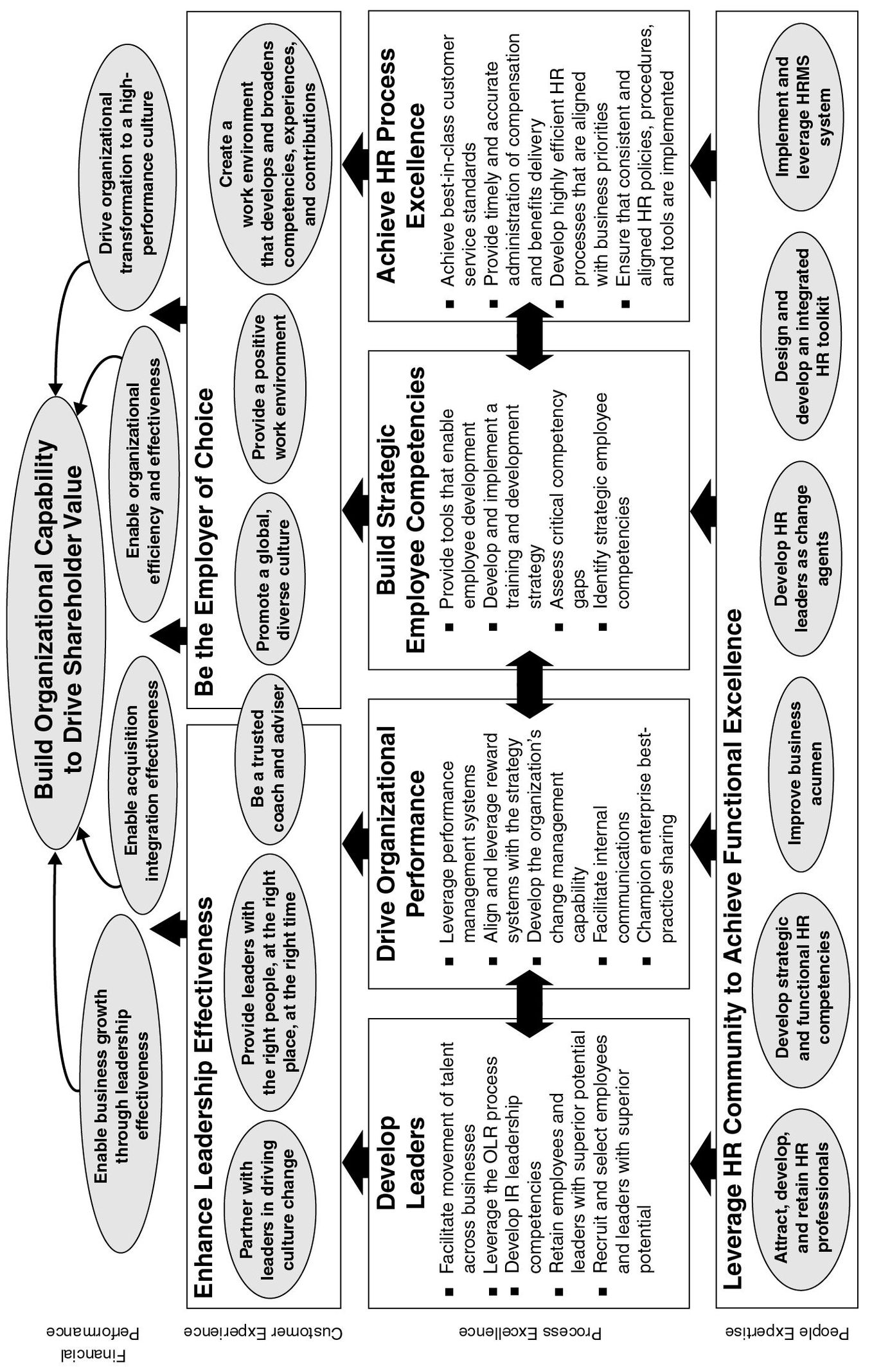

Figure 5-8 presents a Strategy Map template for a human resources unit; Figure 5-9 is the corresponding template for a human resources Balanced Scorecard.5 The two templates have proven to be effective starting points that HR organizations can customize to their actual situations.

The financial perspective of the HR scorecard has two components: HR efficiency and HR effectiveness. Efficiency generally deals with operational issues related to the relative cost of services. Benchmarks relative to external norms are frequently used here. For example, to maintain a focus on productivity, “benefits management cost per employee” can be compared to proposals from external providers.

HR effectiveness can be measured through the linkage scorecard—a small set of measures taken directly from the enterprise scorecard that the HR organization can influence although not directly control. For example, if the corporate strategy is growth through acquisition, the HR linkage scorecard might measure “key staff retention,” “sales created through cross-selling,” or “merger benefits achieved.”

A human resources organization has two kinds of customers: the line business units that HR partners with to deliver its services, and the employees themselves, who are the direct recipients of a full array of HR services. Business units look to HR to provide a professional partnership of knowledgeable support. Some companies, reflecting this professional partnership, rename the customer perspective the client perspective.

The HR organization, in turn, delivers and is held accountable for the solutions negotiated in its strategic services portfolio. Scorecard measures for the business unit partnerships include feedback relative to deliverables in the jointly developed plan (the deliverables are often described in service agreements between a support unit and its business unit customers), and the business unit managers’ assessments of the professional capabilities and service orientation of the HR employees they work with directly. HR’s relationship with its other set of customers—employees—can be measured by a survey of employee satisfaction with the programs and services provided by HR.

The internal process perspective generally is built around three themes. Theme 1, “achieve operational excellence,” focuses on the efficiency with which the many enterprise-level HR programs are delivered. It influences HR’s financial objective to stay within budget while delivering the expected mix and quality of services. This generally means measuring the cost per transaction and the quality and timeliness of HR services, such as compensation and benefits programs, recruiting, training, and annual performance reviews.

Figure 5-8 HR Organization Strategy Map Template

Figure 5-9 HR Organization Balanced Scorecard Template

Theme 2, “develop business unit partnerships,” is often overlooked in practice. It involves developing a formal process for managing relationships with business units. HR should adopt the same kinds of formal customer management processes (planning, account management, and feedback and reviews) that business units use with their external customers. Scorecard measures for this theme might include a status indicator of the level of professional relationships, such as percentage of business units with HR strategic support plans, as well as an account development measure, such as time spent consulting with customers.

Theme 3, “strategic support of business units,” links the HR organization to its strategic services portfolio. Objectives are generally found for the three major areas shown in Figure 5-8: building strategic staff competencies; developing leaders and improving organizational culture; and instilling a commitment to performance management. Responding to the specific requirements to deliver the HR portfolio of strategic services, the HR organization defines specific programs and initiatives to satisfy business strategy requirements (including a budget for initiatives) and a service agreement that defines the specifics of schedules, deliverables, and staffing.

The learning and growth perspective of the HR Strategy Map corrects a typical problem in many HR organizations: the shoemaker’s children going barefoot. Human resources professionals, like all other employees, have specific needs for training, information systems, alignment, and performance management. Particularly as the HR organization shifts its value proposition to providing customized consulting relationships with business units, HR employees must acquire entirely new skill sets. Internal programs for the HR staff should be subjected to the same standards of excellence as those for its business unit customers. HR employees should be viewed as customers of the HR organization for these services, including strategic plans, relationship managers, and feedback processes.

The fourth column in the HR Balanced Scorecard (Figure 5-9) shows the strategic initiatives that support the HR unit’s strategic objectives, measures, and targets. These initiatives are the actions and interventions that lead to successful strategy execution. The initiatives must be budgeted so that informed economic trade-offs can be made. Although most of the initiatives shown in Figure 5-9 support the internal management of the HR organization, those associated with internal processes (I3) comprise the strategic support for business units. This process and associated initiatives produce the deliverables to HR’s customers. The business units must approve the budget for these initiatives as part of the annual plan for the HR unit.

CASE STUDY: HUMAN RESOURCES AT INGERSOLL-RAND

We introduced the Ingersoll-Rand (IR) enterprise strategy and Strategy Map in Chapter 3 (recall Figure 3-4). IR’s corporate-level strategy was to move from being a highly diversified company organized in numerous stand-alone product divisions to becoming a more integrated solutions company that would go to market as a team, integrating the products of several business units to meet a customer’s unique needs. The implications for organization and cultural change were profound. Its strategic theme, “leverage the power of our enterprise through dual citizenship,” spoke to the need for new competencies, new values, the sharing of knowledge, and the expansion of employees’ views beyond the boundaries of their product companies to the IR enterprise as a whole.

Ingersoll’s CEO asked the human resources organization to help implement the dual citizenship theme. Don Rice, senior vice president for human resources and global services, led the effort, starting with developing a Strategy Map for this agenda (see Figure 5-10). The first three process excellence themes—“develop leaders,” “drive organization performance,” and “build strategic employee competencies”—specifically address the corporate strategy agenda. The fourth theme, “achieve HR process excellence,” focuses on the quality and efficiency of HR operational services such as delivery of compensation and benefits.

Collectively, the four process excellence themes deliver the human resources value proposition to its two sets of customers: “enhance leadership effectiveness” of business unit partners and “be the employer of choice” for Ingersoll’s employees. The impact of the HR strategy on financial results would yield results reported in the financial perspective:

- Business growth enabled by better leadership

- Acquisition effectiveness enabled by a team-oriented culture

- Improved efficiency enabled by better management of the HR processes

Figure 5-10 HR Organization Strategy Map at Ingersoll-Rand

Herb Henkel, Ingersoll-Rand’s CEO, commented on the approach taken by IR’s human resources group: “I have never seen anything that so clearly articulates the value that a support function adds to the business. We should use this as a recruitment tool for HR professionals. If anyone couldn’t sign up for this, then we wouldn’t want them in the company.”6

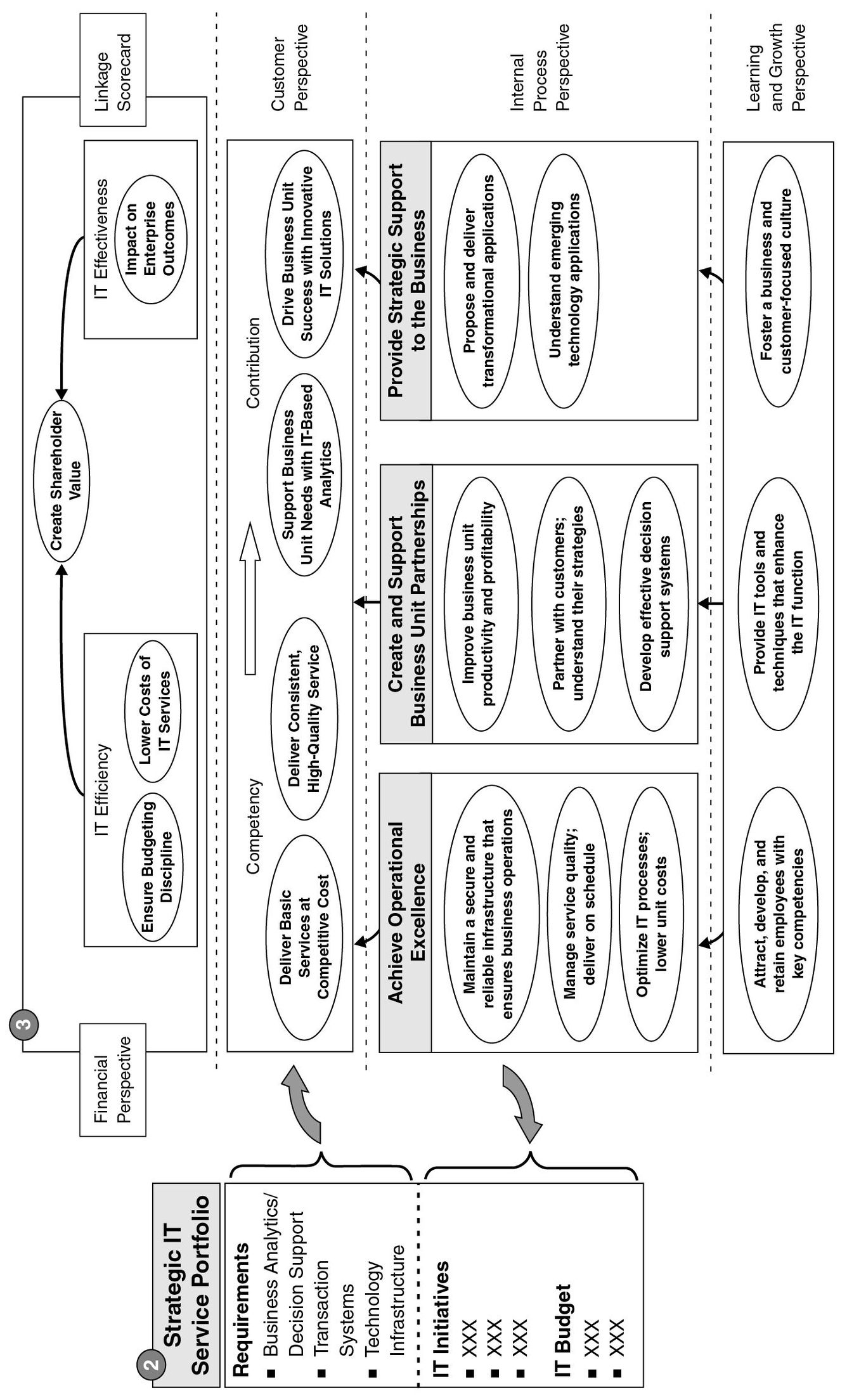

Aligning the Information Technology Organization

Based on our experience with dozens of information technology organizations, we have prepared the generic IT department strategy template shown in Figure 5-11.7 This map illustrates the balance that IT organizations must maintain: be competent at basic, necessary services while developing the capabilities to collaborate with business units, offering them customized services, solutions, and technologies that advance their strategies. This strategic positioning shifts the debate from how much to spend on information technology to how much to invest in IT to advance the organization’s strategic agenda.

The financial perspective reflects objectives to lower the unit costs of supplying basic IT services while also enhancing the enterprise’s outcomes through effective deployment of IT products and services. The IT unit’s strategy gets aligned with the enterprise strategy through the portfolio of strategic IT services, which is derived from the enterprise strategy and negotiated with the business units.

Success in delivering the portfolio of infrastructure and applications is measured, in the customer perspective, at two levels: (1) the basic competency level: the supply of reliable, high-quality IT services at a competitive cost, and (2) the value-adding contribution level, where the IT organization helps business units become more productive and profitable and, ultimately, becomes a vital component in the success of the business units’ differentiation strategies.

The internal process is organized by three strategic themes:

- Achieve operational excellence through access to timely and accurate information and computing resources reliably at reasonable cost. The IT unit provides a cost-effective portfolio of core technology infrastructure—the shared technology and managerial expertise required to deliver computing services to employees—and basic technology applications, including enterprise resource planning (ERP) and other transaction-processing systems, that automate the basic repetitive transactions of the enterprise.

Figure 5-11 Information Technology Organization Strategy Map Template

- Create and support business unit partnerships. The IT unit becomes the trusted adviser to operating managers on how to deploy information technology to improve business unit profitability and external customer satisfaction. The technology includes analytic applications: the systems and networks—such as customer relationship management and activity-based costing (ABC)—that promote analysis, interpretation, and sharing of information and knowledge.

- Provide strategic support to the business. The IT unit supplies innovative and emerging technology-based solutions that help business units position themselves for competitive advantage. It introduces transformational applications, the systems and networks that change the prevailing business model of the enterprise.

The first theme helps to demonstrate the group’s ability to supply basic IT capabilities to business units at competitive costs, along with reliable service delivery and consistent quality. The second theme enables the group to develop solutions customized to the needs of each business unit. In this way, the IT department becomes a strategic partner of the business unit and participates with it in creating and executing its strategy. With the third theme, solutions leadership, the IT group offers product-leadership computing that supports the business units’ differentiation strategy by offering innovative information-based solutions to customers and suppliers.

Information technology support units might opt only for initiatives in the first theme: supplying basic IT infrastructure and applications at low cost and with high reliability and availability. The parent organization, however, might then decide that these basic IT products and services can be obtained most efficiently by outsourcing the function to an external supplier that enjoys tremendous scale and global economies in acquiring and operating IT resources. Internal IT groups will likely want to differentiate themselves from external providers by offering the themes of strategic partnership and solutions leadership to its business unit partners. These require higher spending on IT resources but offer more than commensurate returns through high-value-added products, services, and solutions.

Our colleague Robert S. Gold argues that the typical IT organization follows a sequential strategy of successively satisfying a business unit’s hierarchical needs.8 The IT organization starts by demonstrating its competency in the consistent, reliable, low-cost supplying of basic information capabilities and services, such as those listed in theme 1. Success along these dimensions is necessary but usually is not sufficient to meet all of a business unit’s IT needs. It eliminates dissatisfaction but does not by itself contribute to value creation for the business unit.

Once the IT organization’s competency has been established, it earns the right to move to the capabilities identified in the second and third themes. First, it develops alliances with business units, contributing to their productivity and profitability strategies by offering customized initiatives and applications. The highest level of IT support occurs when IT customizes emerging technology capabilities that position the business unit for distinctive competitive advantage.9

The employee objective in the learning and growth perspective identifies the critical skills required for the IT unit’s people to deliver on the three-pronged strategy of operational excellence, business partnerships, and industry-leadership solutions. The IT unit, of course, needs its own technology support to manage and deliver its offerings. It often must shift the culture away from being a sandbox in which technology mavens happily play by themselves. It must instill a new culture of customer focus in which IT professionals understand the operations and strategies of business units and supply an appropriate mix of products, services, and solutions that create success for their customers, the internal business units.

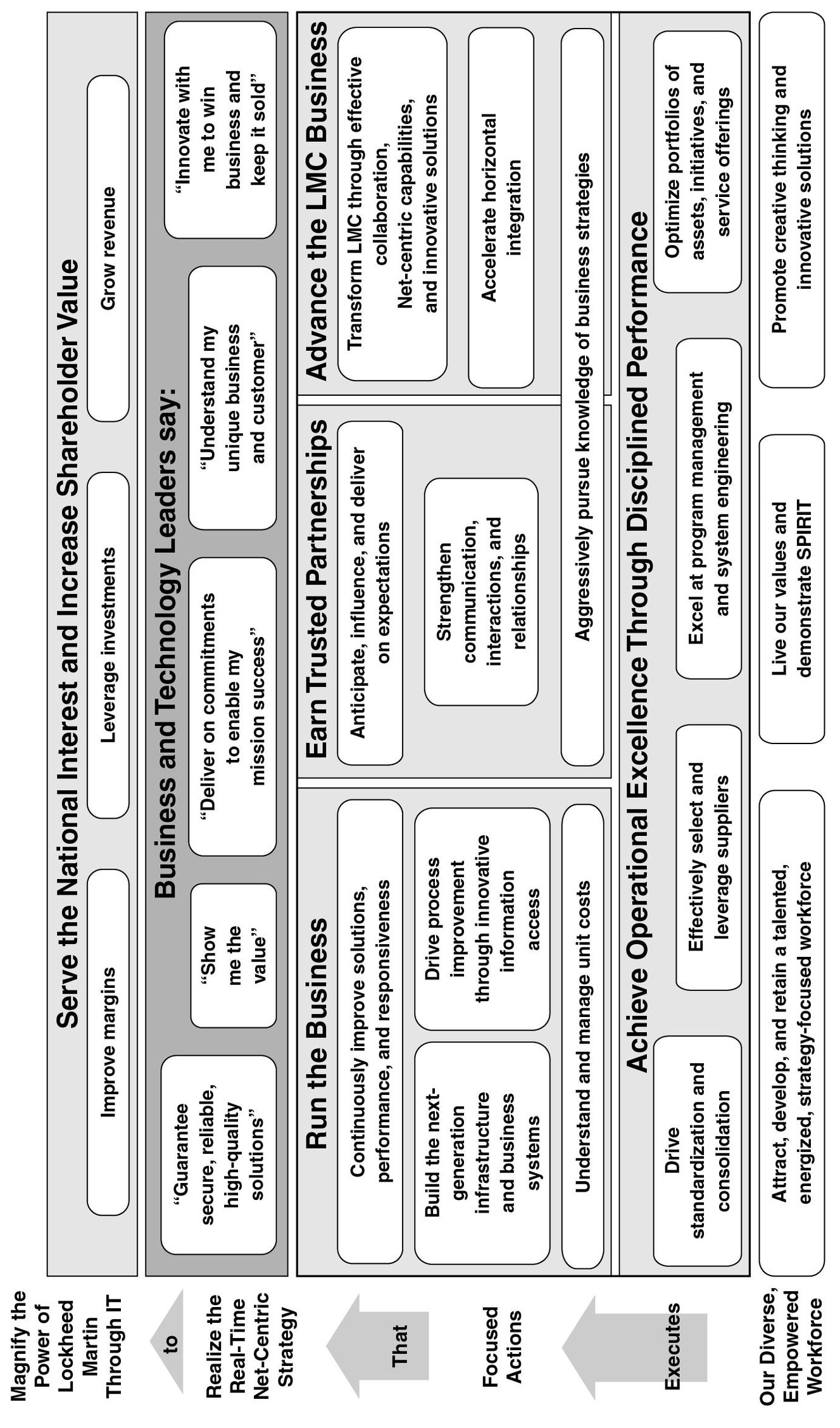

We illustrate the development of an IT Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard for the large information systems group at Lockheed Martin Corporation.

CASE STUDY: LOCKHEED MARTIN ENTERPRISE INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Lockheed Martin Corporation became the country’s largest defense contractor after the merger of Lockheed and Martin Marietta in 1995. Sales in 2004 were $35.5 billion, and the company had a backlog of $76.9 billion. Its largest customer (62 percent) is the U.S. Department of Defense, with other customers including nondefense government (including homeland security), 16 percent of revenues; international sales, 18 percent; and domestic commercial, 4 percent.

Lockheed Martin’s enterprise information systems (EIS) organization has more than four thousand employees working in its Orlando, Florida, headquarters and in several dozen decentralized units around the United States, including Washington, D.C.; Fort Worth; Sunnyvale, California; and Denver. “We’re trying to make strategy a part of everyone’s job,” says Ed Meehan, vice president of operations for Enterprise Information Systems.

Business unit leaders, especially since the 1995 merger, were concerned because the company’s IT units operated in stovepipes and silos. This problem was especially acute because IT capabilities were at the heart of the company’s strategy to be the leader in “Net-centered” capabilities. Lockheed Martin expects its technology to be at the center of how the military will organize and fight in the information age, linking various systems and sensors to exponentially increase the military benefit of those systems that otherwise operate independently.

To meet its new challenges as a value-added IT provider to the corporation, EIS adopted a complete customer solutions strategy to become the supplier of choice for internal IT services for the corporation. It also wanted to serve external customers by helping Lockheed Martin businesses win large IT-related contracts from the government, such as those expected from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

EIS launched a Balanced Scorecard program to align its various operating departments with the overall EIS strategy and also with the strategies of the corporation. The BSC would help EIS become the credible innovator and supplier of cutting-edge, net-centric capabilities. Figure 5-12 shows the EIS Strategy Map. The language reading upward along the left side of the map (“Our diverse, empowered workforce . . .”) provided what one EIS leader called a Reader’s Digest version of the map: a way to quickly both introduce the structure and set up the content when the map is presented to audiences new to the Strategy Map concept.

EIS leadership identified business and technology leaders within Lockheed Martin as their key customers and used the voice of the customer to describe five customer objectives. Reading from left to right, these objectives move from “table stakes” (“Guarantee secure, reliable, high-quality solutions,” “Show me the value,” and “Deliver on commitments . . .”) to objectives that more fully realize potential value from Lockheed Martin (“Understand my unique business and customer” and “Innovate with me to win business and keep it sold”). EIS leadership understood that the credibility EIS would establish following its success in the table stakes objectives was a prerequisite to EIS being seen by its internal customers as a contributing partner in winning business, and not merely as a service provider.

Building on objectives for an “energized, strategy-focused workforce,” the four-themed structure of the internal process perspective reflected this left-to-right movement from competency to contribution. The “disciplined performance” theme contained objectives and broad efforts throughout EIS to enable continuous improvement in overall EIS performance; efforts to drive standardization and consolidation, to manage the use of external suppliers, to employ the disciplines of program management and systems engineering, and to optimize portfolios served as a foundation for the objectives in the themes “run the business,” “earn trusted partnerships,” and ultimately “advance the business.”

Figure 5-12 Lockhed Martin Entreprise Information Systems Strategy

To run the business, EIS recognized that its customers cared primarily about quality and cost. By understanding and managing unit costs, EIS sought to isolate costs from demand and to better manage their impact on total IT cost. Development and enhancement of next-generation infrastructure, process improvement, and improved solutions, performance, and responsiveness were highlighted as key objectives. But satisfying these objectives was only the beginning.

By aggressively pursuing knowledge of business strategies, EIS leadership sought to strengthen relationships with its partners and to anticipate and deliver on their expectations. With this improved relationship, EIS expected to empower horizontal integration within Lockheed Martin and better realize the corporation’s net-centric capabilities. “We’re trying to magnify the power of Lockheed Martin through information technology,” Meehan says. “We’re making people’s ability to get information more seamless.”

Placing the value perspective at the top of the Strategy Map, EIS leaders reinforced the financial contribution that the EIS organization enables in the Lockheed Martin enterprise: to improve margins by managing cost, to leverage investments in existing IT capabilities, and to grow revenue.

By mid-2005, EIS had cascaded this Strategy Map into its ten functional areas and was already seeing heightened awareness and engagement with the EIS strategy among its workforce.

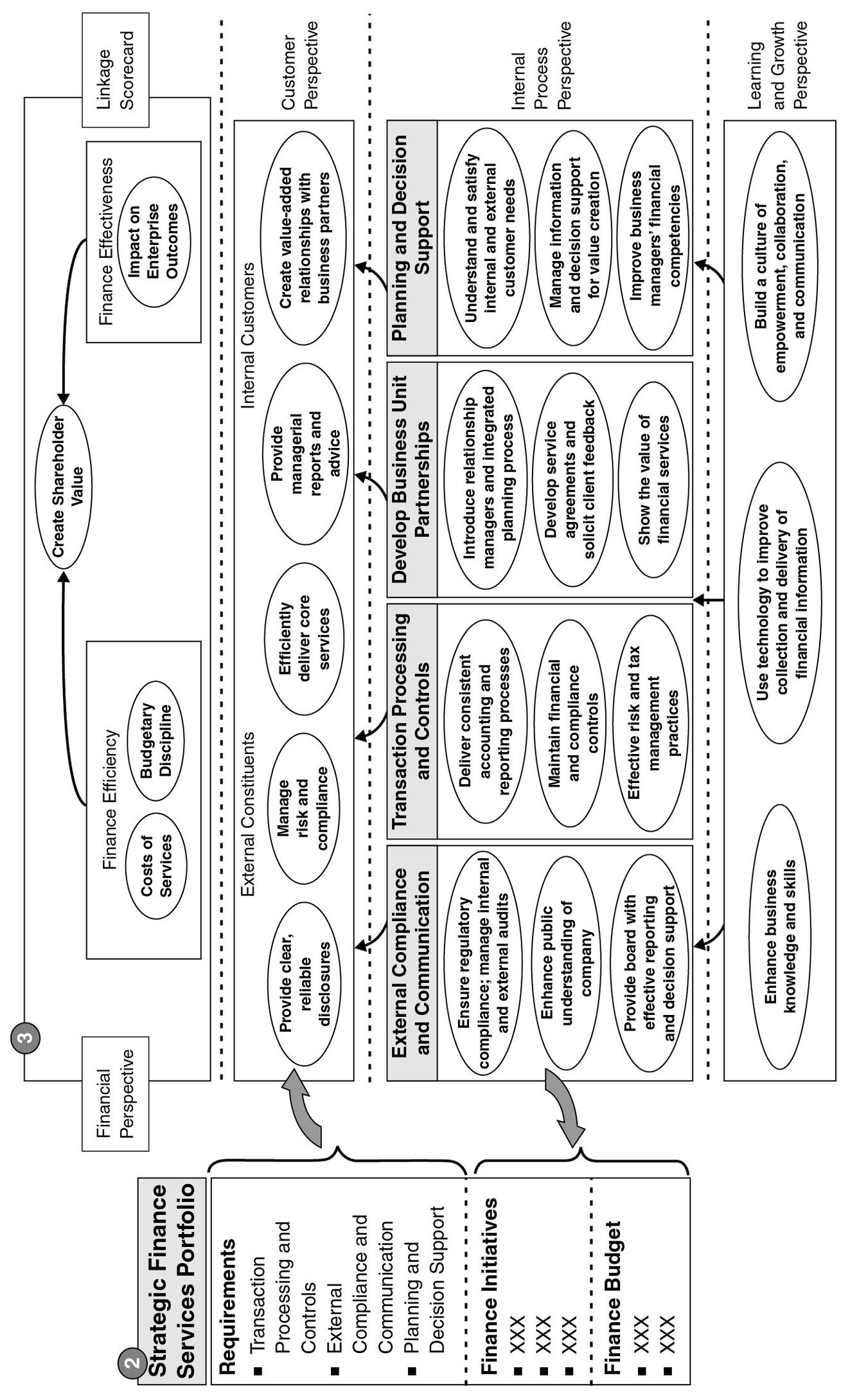

Aligning the Finance Organization

Finance, the third unit we profile, is perhaps the most powerful of all support units.10 It measures and controls the organization’s financial resources, and it interprets and enforces numerous accounting standards and compliance requirements imposed by external regulatory authorities. It also communicates with the enterprise’s diverse constituencies, including shareholders, analysts, the board of directors, tax authorities, regulators, and creditors.

The finance function has encountered dramatic changes in the past decade. Corporate reporting scandals triggered the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, which forced increased scrutiny of organizations’ reporting, internal processes, and controls. Electronic technologies, such as the Internet, revolutionized payments, billing, inventory, and supply-chain processes. The new knowledge-based economy, where 80 percent or more of corporate value is derived from intangible assets, required measurement and management systems that go beyond traditional budgets and financial reporting. Moreover, new measurement approaches, such as economic value added, rolling forecasts, activity-based cost management, and Balanced Scorecards, were introduced. Contemporary finance organizations must cope with the newly imposed external constraints and requirements while simultaneously applying new measurement and management methodologies that help drive the organization’s strategy implementation into the future.

Finance groups are responding to these challenges by extending their historic scorekeeping function to forge new partnerships with business units and corporate executives. A recent study described the CFO’s new role as “chief performance adviser.”11 A Booz Allen Hamilton study found that “chief financial officers are viewed by their CEO as their primary aides in driving company-wide transformation efforts.”12 Clayton Daley, CFO of Procter & Gamble, described the dual roles for today’s CFO: “I consciously think of myself as wearing two hats. I am responsible for traditional accounting issues: cash flow, capital, and cost structures. But my role is increasingly linked with strategy and operations.”13

We can capture these multiple responsibilities using a generic finance function Strategy Map, as shown in Figure 5-13. The financial objectives are to operate the finance function efficiently and stay within the budget authorized for its mix of regulatory, compliance, control, and decision support activities. The efficiency theme also incorporates assisting the enterprise in achieving its cost-reduction and productivity objectives through an effective, adaptive budgeting process, disciplined resource allocation and investment processes, and operational reports and feedback that support employees’ continuous improvement and productivity programs. Its effectiveness objective, derived from objectives on the enterprise Balanced Scorecard affected by the finance function, will share enterprise success measures such as revenue growth, return on equity, and economic profit.

The finance Strategy Map reflects two types of customers: external constituents and internal business partners. External constituents—including shareholders, the board of directors, analysts, and regulators—look to the finance function to provide high-quality quarterly and annual financial reports and disclosures, corporate risk management, and controls and compliance that ensure that the enterprise is operating well within legal and ethical boundaries. The internal business customers want consistent, low-cost execution of basic accounting and finance processes—payroll, accounts receivable and payable, monthly closings, and consolidation—as well as informative reports to management and financial advice and support for its strategies.

Figure 5-13 Finance Organization Strategy Map Template

The internal processes that deliver these benefits to internal and external customers are built around four themes.

External compliance and communication: Address the needs of external constituents through regulatory compliance, effective communication of the company’s economics and strategy, board reporting and decision support, and oversight of internal and external auditing processes.

Transaction processing and controls: Become operationally excellent in delivering reliable transaction processing, record keeping, financial reporting, tax and risk management, and internal controls and compliance. These are the necessary processes that any enterprise expects its finance function to perform well.

Develop business unit partnerships: Build an understanding of business unit requirements for financial management support, and install a professional process to deliver this understanding.

Planning and decision support: Deliver the strategic support plan developed jointly with the business units; become business unit managers’ trusted financial advisers by supplying and interpreting financial and nonfinancial information and by providing a portfolio of analytic tools that supports business decisions, management control, and strategy implementation.

The finance function’s learning and growth objectives describe the transformation requirements of its new role. Finance must maintain its historic competencies in accounting, financial reporting, compliance, and controls. But it must build on these competencies to develop new competencies among its employees that enable them to understand operations and strategy and to work effectively with business unit line managers. Many companies now require that all finance managers spend time working in operating units, often in line positions. Johnson & Johnson sends its new finance function hires through a two-year training program to enable financial managers to have a focus on customers, an understanding of the marketplace, an aptitude for teamwork, and the ability to be positive change agents.14

Almost all routine processing and reporting of transactions are now automated, requiring finance personnel to have strong capabilities in information technology. They must ensure the validity and integrity of financial systems and must enhance transaction-processing systems, such as ERP, with higher-level analytic applications that transform raw data and transactions into information and knowledge for managers.

To excel at the internal process theme of planning and decision support, the finance function cannot be only an objective, independent scorekeeper on the sidelines. It needs a new culture and climate where its professionals become the value-added financial advisers to managers and executives. But while they are transforming into this “chief performance adviser” role, finance managers must be prepared, as a former Federal Reserve chairman once said was his job, to take away the punch bowl when the party becomes a little too exuberant. Finance managers must have a strong value system that helps them achieve a balance between being contributing and loyal team members and representing the needs and expectations of external constituencies for integrity, control, risk management, and long-term shareholder value creation.

CASE STUDY: HANDLEMAN FINANCE DEPARTMENT

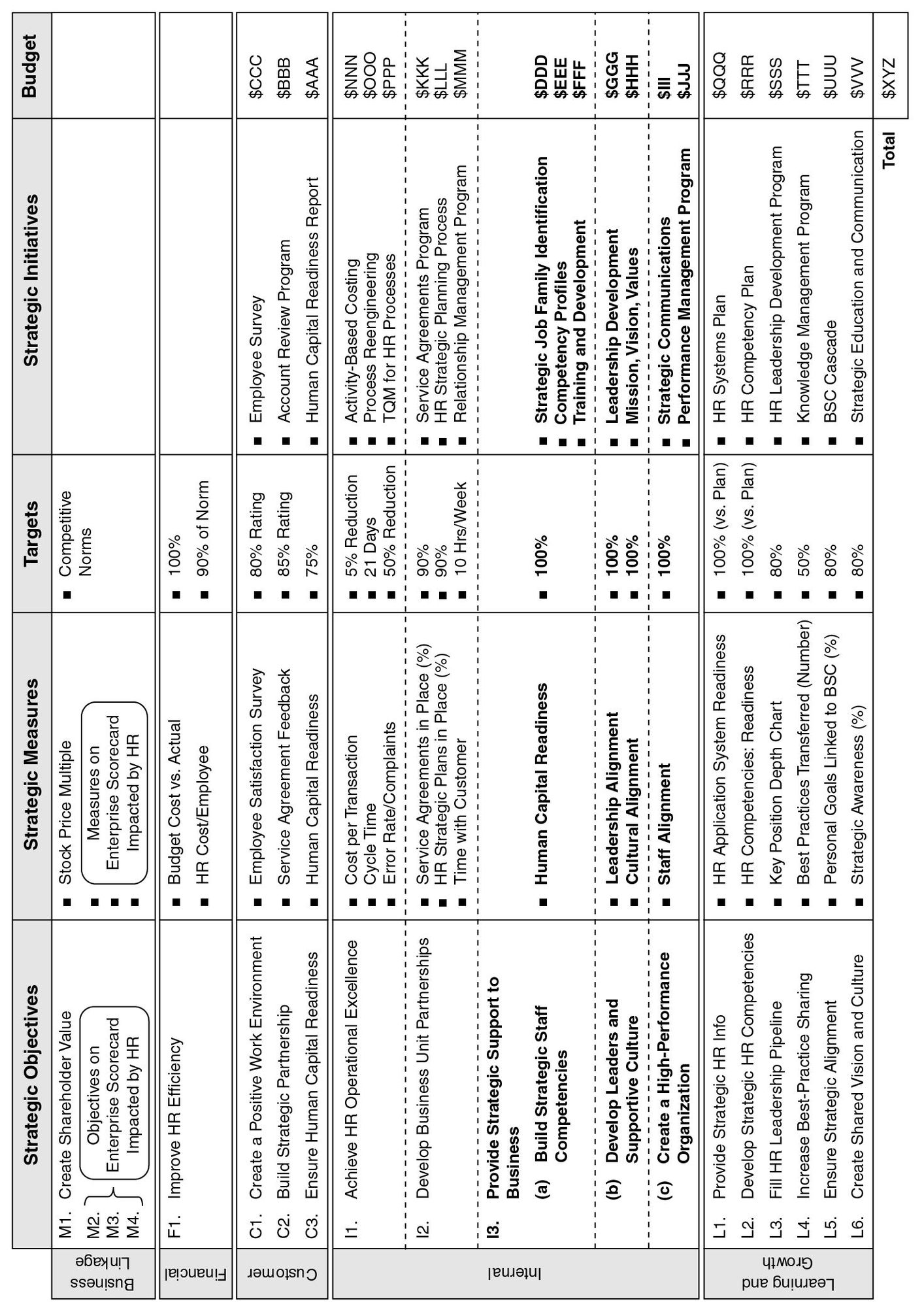

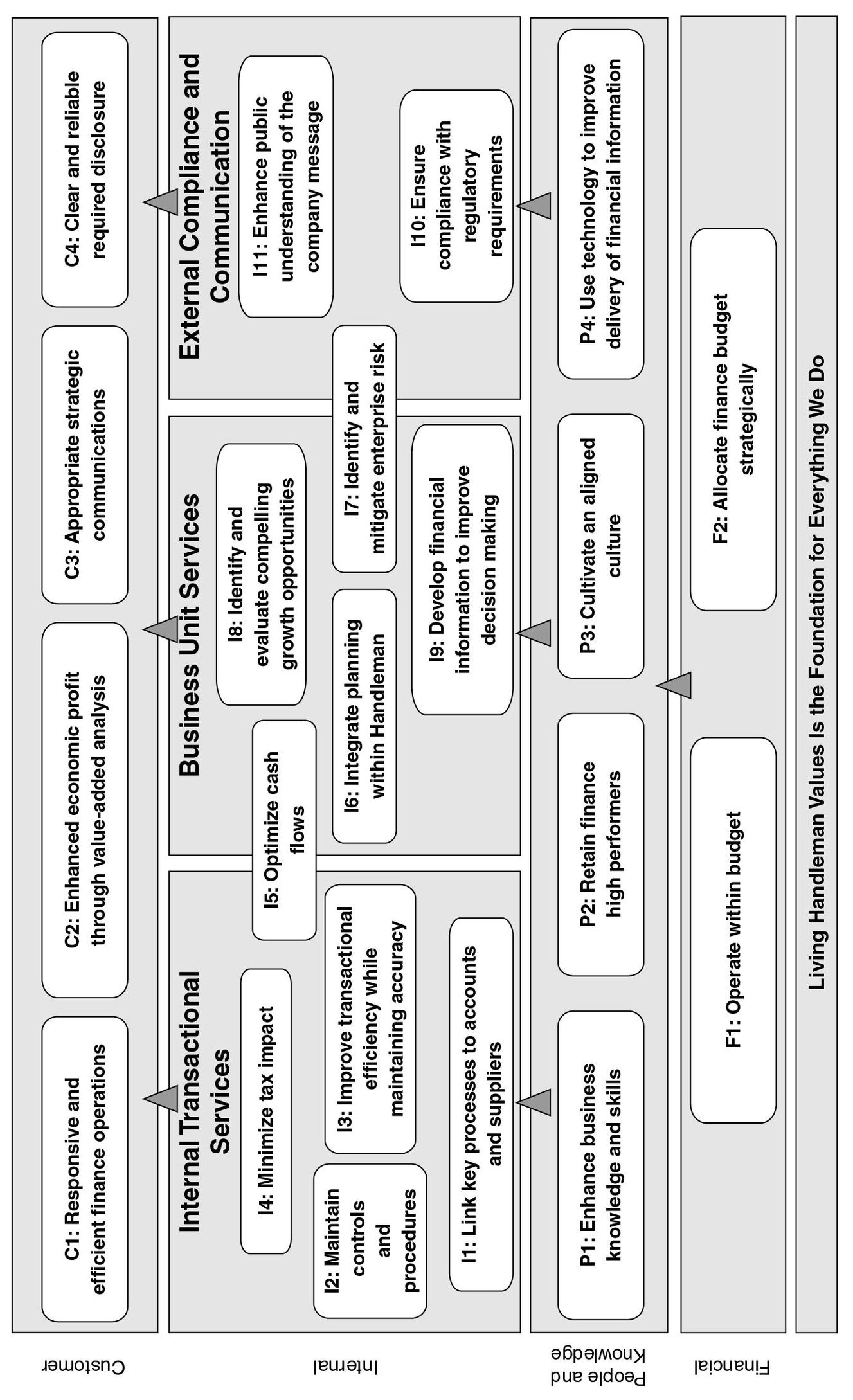

We illustrate a finance department Strategy Map (Figure 5-14) and Balanced Scorecard (Figure 5-15) by continuing with the Handleman example, introduced earlier in this chapter. Its finance unit Strategy Map provides a comprehensive overview of a corporate finance department that includes advice as well as audit, investor relations, tax, controllers group, treasury, and internal financial services within one scorecard.15

The Handleman finance group defined four key customer objectives:

C1: Responsive and efficient finance operations. The finance group will be responsive and efficient. It will focus on reducing the time that is spent on daily transactional tasks and increase the time spent on analytical functions to enhance decision making while maintaining a very high standard for accuracy and controls.

Figure 5-14 Handleman Finance Division Strategy Map

Figure 5-15 Handleman Division Balanced Scorecard

C2: Enhanced economic profit through value-added analysis. Finance will support the business customers in their efforts to maintain and grow the profitability of the company. This support is provided through the thorough investigation and useful analysis of business-related information to facilitate proactive business initiatives. Finance must focus its limited resources in areas that capitalize on enhanced value for its customers.

C3: Appropriate strategic communications. The finance communications plan will increase the company’s price/earnings multiple by employing disciplined practices of clear and visible external communications of the company’s strategy.

C4: Clear and reliable required disclosure. Finance will provide reliable financial information for investors and creditors to make decisions. This information must meet regulatory standards for accuracy and timeliness.

The second customer objective, C2, links the finance group to the success of the business units. With this objective, the finance group commits to working closely with the business units, as their economic partner, to help them increase their economic profits.

The four customer objectives are driven by eleven internal process objectives, organized by three themes: internal transaction services, business unit services, and external compliance and communication. The key internal processes, within the business unit services theme, for becoming an economic partner are as follows:

I8: Identify and evaluate compelling growth opportunities. Finance will play the leading role in helping Handleman grow by acquisitions or partnerships with other firms that can provide quicker and more effective access to new customers, new markets, or new content and suppliers. In addition, finance will identify strategic transactions that expand the company into new businesses, such as rebundling existing offerings, growing the online business, or entering other entertainment or nonentertainment product lines.

I9: Develop financial information to improve decision making. Finance, to enhance business managers’ decision making, will migrate from a primarily transactions-based organization to one that is analytical. This will allow finance to provide the delivery of timely, useful, and fact-based financial information.

The first two “people and knowledge” objectives in the finance Strategy Map are to develop the competencies necessary for the new finance strategy to be implemented, and to retain the experienced, trained, high-performance members of the finance staff. The third objective, “cultivate an aligned culture,” links to the business partnership theme by highlighting the need for those in the finance function to work together to help the business achieve its growth and profitability objectives:

P3: Cultivate an aligned culture. To make the maximum contribution to achievement of the corporate and finance strategy, the finance organization needs to be focused in the same direction. Silos within the functional finance areas need to be eliminated. We are a team, with each individual playing a part in achieving our strategy. We must all understand how we contribute to the finance Strategy Map and must take accountability for our part of the plan. To create this alignment, we will, when necessary, modify our processes, including our compensation systems, internal communications processes, and organizational structure.

The Handleman Strategy Map and accompanying Balanced Scorecard provide an excellent example of the challenges facing a twenty-first-century finance organization. It must continue to excel at its traditional roles of transaction processing, internal controls, external communications, and compliance while also developing the skills and a new culture to forge strategic partnerships with business units, helping them create and sustain higher shareholder value.

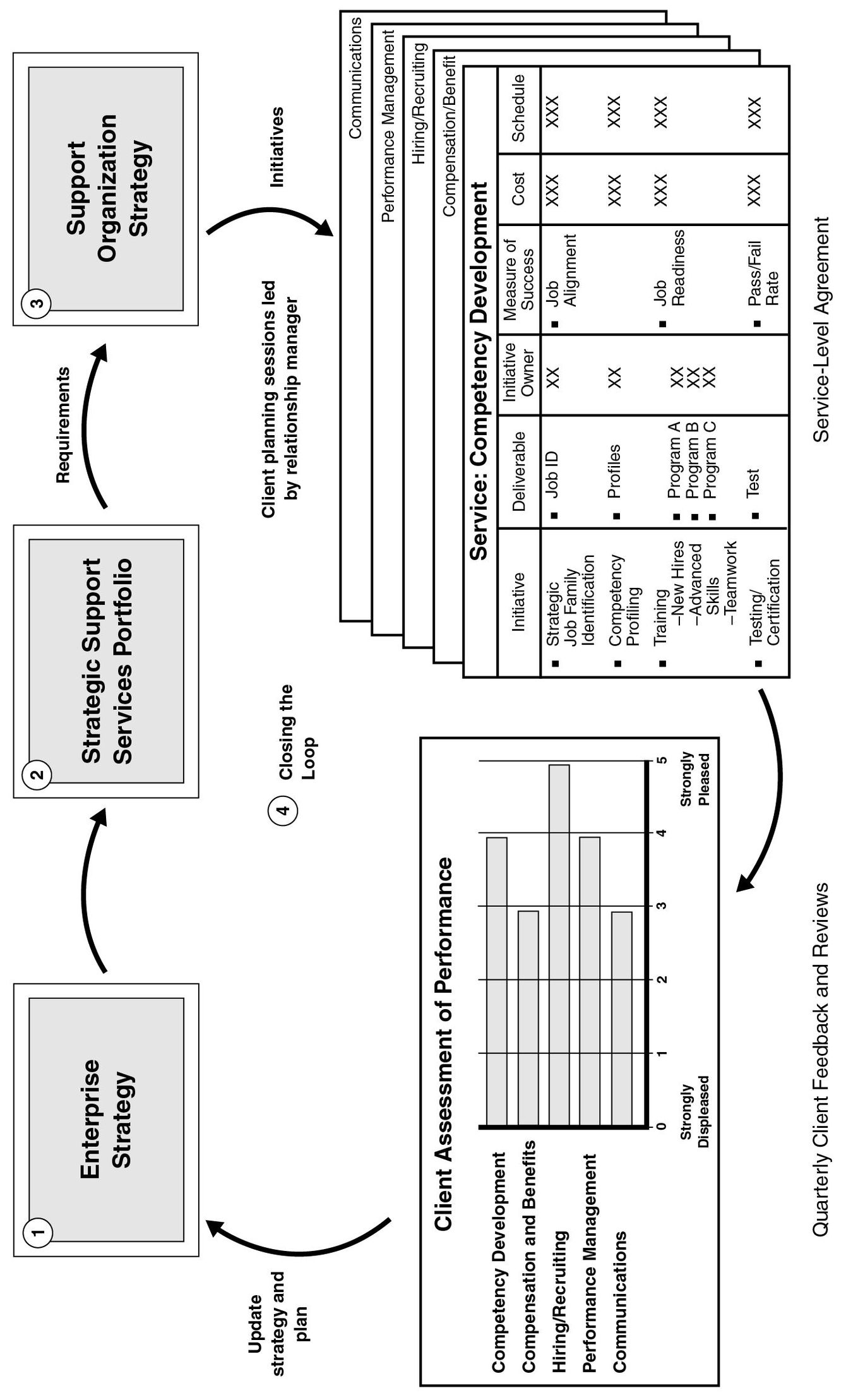

CLOSING THE LOOP

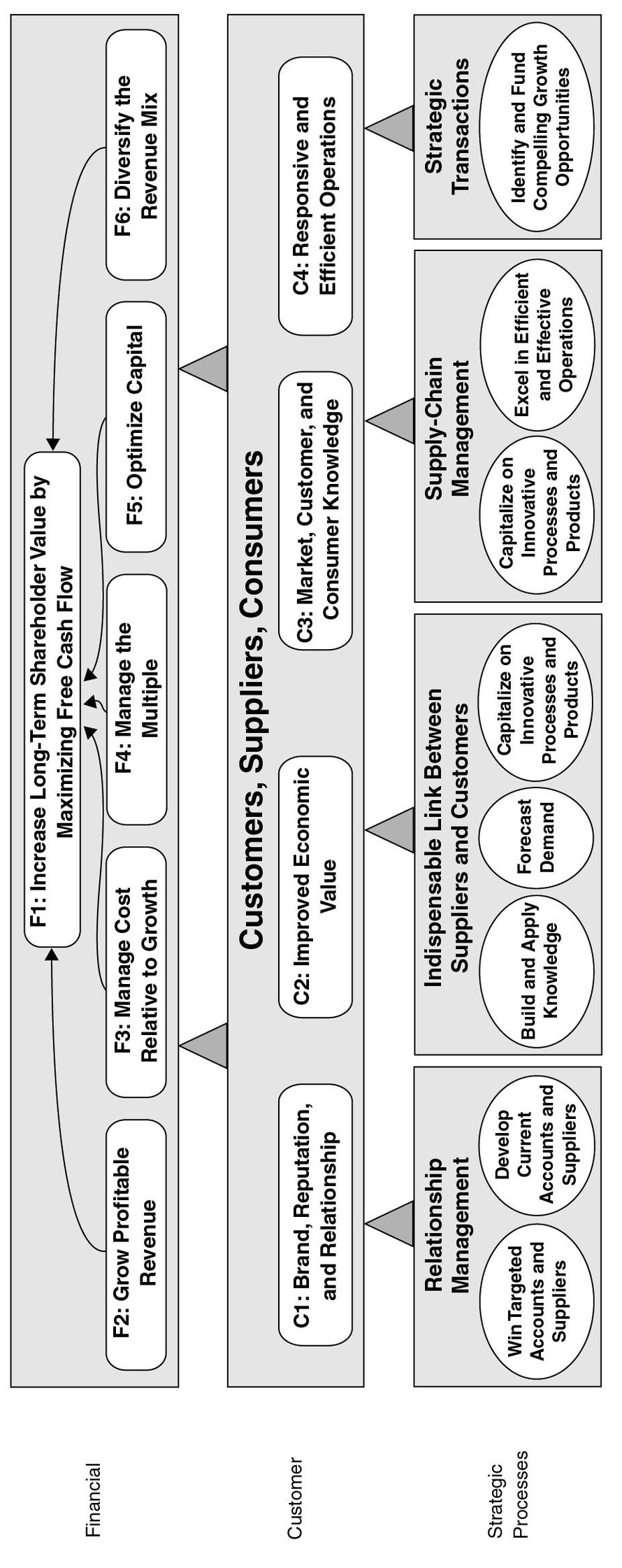

We have illustrated how to develop Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards that align support units with business units and the enterprise. Alignment, however, must be actively managed as an ongoing process, and not just described with maps and scorecards. As illustrated in Figure 5-16, an effective alignment process for a support unit includes the following components.

- A relationship manager from the support unit, responsible for the alignment

- An integrated planning process, in which the support unit participates, that defines the unit’s role to support business unit objectives

Figure 5-16 Closing the loop: A Process to Achieve Support Unit Alignment

- . Service agreements that define the support unit’s deliverables, service levels, and costs, including initiative owners to ensure that each initiative in the strategic services portfolio is delivered effectively to the client, the business units

- Internal customer feedback sessions based on the service agreement

- Assessment of costs and benefits to validate the contribution of the support unit

Relationship Managers

The first step in building a business unit partnership is to assign someone to lead and manage the relationship. It’s impossible to conceive of human resource consultants from Hewitt or information technology consultants from Accenture attempting to manage a client relationship without identifying a relationship manager. Yet, according to our research, only 33 percent of IT organizations and 43 percent of HR organizations follow the practice of assigning relationship managers to the business.16

IBM Learning (described in Chapter 4) started its alignment process with business units by appointing learning leaders to work with each major business unit. A learning leader had to understand the business unit strategy, translate that strategy to a Strategy Map, and educate the client on how training would enhance the strategy. The learning leader facilitated a planning process that identified learning solutions and coordinated their development and delivery. Through these activities, learning leaders forged a strategic partnership with their business unit counterparts.

J. D. Irving, a diverse family-owned conglomerate headquartered in New Brunswick, Canada, identified alignment champions that it assigned to each of eight major business groups. The alignment champions owned the process for developing, communicating, and reviewing business unit plans, measures, and incentives. These change agents helped business unit managers develop their leadership behavior, share best practices, and align their business units with corporate objectives.

Integrated Planning Process

Steps 1, 2, and 3 in Figure 5-17 describe an effective, integrated planning process for support units. The process assumes that business units already have Strategy Maps. If business units do not have a clear articulation of their strategies—one that can be translated into a Strategy Map—then alignment with support functions is considerably more difficult. Relationship managers can be consultants to their business units, helping them to create Strategy Maps when they don’t have one. Building Strategy Maps is an analytic, structured process that relationship managers can learn.

Figure 5-17 Service-Level Agreements and Customer Feedback Process

After a member of the human resources department of one organization helped a business unit manager build a Strategy Map of his business, the manager observed, “This is the best description of my strategy that I’ve ever seen. I never expected to learn something like this from our human resources department.” The planning exercise was a clear step in establishing a professional partnership based on mutual respect.

Service Agreements and Client Feedback

The strategic planning process produces a set of initiatives for the support unit to develop and deliver for the business unit. These deliverables are the essential drivers of results in the business unit; for example, if an effective training program isn’t prepared in time, employee skills will not be developed and the results of new programs, such as quality or sales, will be delayed.

The commitments to deliver the services or programs associated with the initiatives are frequently translated into service agreements that precisely define the support unit’s deliverables. The service agreement provides the basis for managing the relationship between the business unit and the support unit and provides an explicit basis for accountability for results.

An initiative owner is assigned to help keep the support unit focused on delivering each approved initiative in its portfolio and fulfilling the service agreement. The initiative owner works with an assigned sponsor (or customer) from the line organization. The support unit’s executive team manages its portfolio of strategic initiatives as an integrated portfolio, just as venture capital managers actively manage their portfolios of strategic investments. The executive team reviews the status of its strategic services portfolio each month and conducts detailed reviews of specific initiatives at least quarterly.

These monthly meetings promote a professional dialogue about the support unit’s performance and about its shared responsibility with business units. One business unit manager commented, “These quarterly reviews allow us to see problems coming much sooner than in the past. We’re working much better as a team, with less finger-pointing. This has pointed out that good performance from purchasing is a shared responsibility.”

Costs and Benefits

Relationship managers must ultimately ensure that the services provided by their support units meet the objectives established by the business units they partner with. This goes beyond simply showing that initiatives, agreed to by both parties, were delivered on time and on budget. The support unit, led by the relationship manager, must accept shared responsibility for results with the line organizations. If the services don’t produce results, then the support unit bears some of the responsibility.

We generally recommend that when organizations design an incentive compensation system, they base half of the bonuses of support unit staff on results achieved in the businesses they serve. This approach keeps everyone focused on success, as defined by the enterprise.

EXTENSIONS

We have described the strategic services portfolio and Strategy Maps of three key support units that virtually all organizations contain. Rather than a single chapter, we could devote a book to this subject to reflect the alignment of many other support units—such as purchasing, research and development, legal, treasury, real estate, environment, safety, quality, and marketing—with business unit and enterprise strategy. Even the big three we’ve covered in this chapter—human resources, information technology, and finance—typically have multiple departments that work on specialized functions.

For example, an enterprise IT group might include departments having specific responsibility for operations, technology, systems, applications, and security. Therefore, large support units need to use their group-level strategy as the basis for cascading strategy and scorecards down to their operating departments, just as the corporate strategy is cascaded down to business unit strategies.

SUMMARY

Support units contribute to organizational synergies when they align their activities with business unit and enterprise priorities. Although this statement may seem obvious, most organizations do a poor job of creating such alignment. Internal support units need to build new ways of managing that create partnerships and alignment with their internal customers. Such alignment constitutes the principal economic justification for retaining internal shared-services units rather than outsourcing their services to lower-cost providers.

In this chapter, we articulate the basic principles involved in aligning support units with enterprise and business unit strategies. Start by understanding and identifying the specific parts of the strategy that the support unit can influence. These objectives should appear as high-level objectives on the support unit scorecard (the linkage scorecard); they form the common thread between the business and the support unit.

Customer strategies build partnerships with the client (the customer solutions strategy most typically adopted by support units) and feature client objectives as high-level outcomes on the unit’s Strategy Map. Internal process objectives can typically be represented via three strategic themes. One represents the low-cost, reliable, high-quality supply of basic, nondifferentiated services. Another addresses the building of business unit partnerships, and the third emphasizes the creation and delivery of innovative services that help business units succeed with their strategies.

The learning and growth objectives include providing support employees with the new skills, knowledge, and experience they need so that they can become trusted advisers to business unit managers. In this role they exploit new IT services and applications to deliver services more efficiently and effectively; to transform the culture from one focused on functional excellence to one focused on customers; and to deliver solutions that add value to business partner customers. With these guidelines in mind, organizations should be able to align their internal support units to participate in activities that create additional value and synergies for the enterprise.

NOTES

“Implementing the Balanced Scorecard at FMC Corporation: An Interview with Larry D. Brady,” Harvard Business Review (September–October 1993): 146.

See “Responsibility Centers: Revenue and Expense Centers,” Chapter 3 in R. Anthony and V. Govindarajan, Management Control Systems, 8th edition (Chicago: Irwin, 1995), 107–123.

At least one critic, however, would dispute this statement; see N. Carr, “IT Doesn’t Matter,” Harvard Business Review (May 2003).We, with others, respectfully disagree and believe that effective alignment of the IT resource with strategy can be a distinctive source of value creation.

P. Weill and M. Broadbent, Leveraging the New Infrastructure: How Market Leaders Capitalize on Information Technology (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998), 37–39.

Cassandra Frangos, a colleague of ours at the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative, has been a major contributor to our knowledge of building human resources Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards.

Henckel note TK.

Robert S. Gold, a colleague of ours at the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative, has been a major contributor to our knowledge of building information technology Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards.

The motivation for this work comes from F. Herzberg’s adaptation of the hierarchical needs model of A. Maslow, Motivation and Personality, 3rd edition (New York: HarperCollins,1987). The concept of first satisfying hygiene factors (i.e., competency) before addressing motivation (i.e., contribution) was articulated in F. Herzberg, B. Mausner, and B. Snyderman, The Motivation to Work, 2nd edition (New York: Wiley, 1959).

R. S. Gold, “Enabling the Strategy-Focused IT Organization,” Balanced Scorecard Report (September–October 2001).

Arun Dhingra and Michael Nagel, colleagues of ours at the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative, have been major contributors to our knowledge of building finance unit Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards.

“The CFO as Chief Performance Adviser,” report prepared by CFO Research Services in collaboration with Price WaterhouseCoopers LLP, CFO Publishing Corporation, Boston, March 2005.

V. Couto, I. Heinz, and M. Moran, “Not Your Father’s CFO,” Strategy + Business (Spring 2005): 4.

Ibid., 4.

Ibid., 10.

Observe that Handleman’s finance unit has chosen to place its financial perspective at the base, and not the pinnacle, of its Strategy Map. This illustrates our earlier discussion of the option to treat support units as nonprofit organizations, stressing service to clients and customer objectives as the top-level objectives.

SHRM/Balanced Scorecard Collaborative, “Aligning HR with Organization Strategy,” survey research study 62-17052 (Alexandria, VA: Society for Human Resources Management, 2002); “The Alignment Gap,” CIO Insight, 1 July 2002.