CHAPTER TWO

CORPORATE STRATEGY AND STRUCTURE HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

THE PROTOTYPICAL ORGANIZATION, at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, was Adam Smith’s pin factory, a small, focused enterprise producing a narrow range of products for its local customers. The organization structure of Smith’s pin factory was simple: an owner-entrepreneur with perhaps a supervisor and several hired workers. The owner-manager ordered materials, hired and paid the employees, supervised production, and performed marketing, sales, billing, and cash collections.

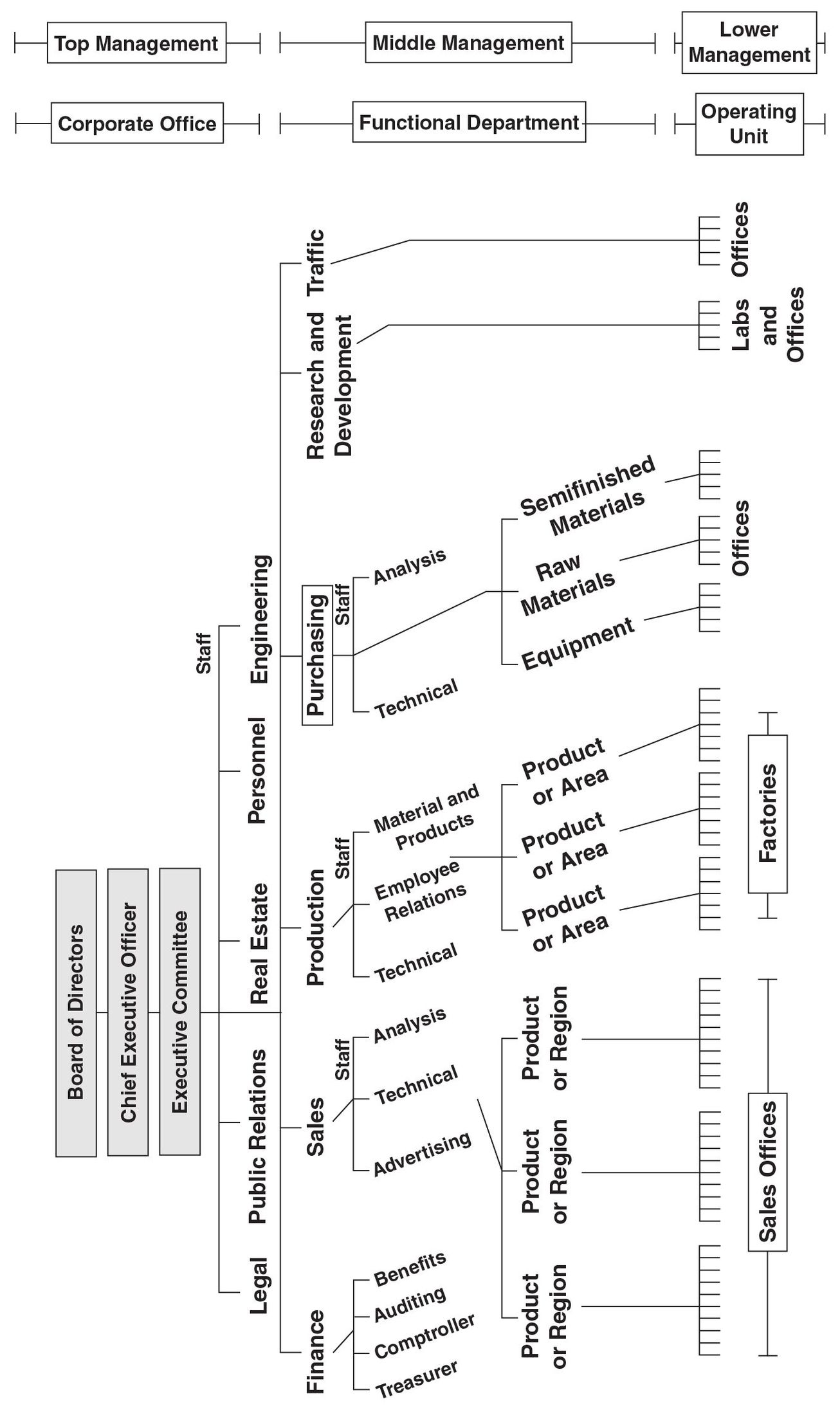

The Second Industrial Revolution, starting in the middle of the nineteenth century, saw the growth of much more complex capital-intensive industries, such as primary and fabricated metals, chemicals, petroleum, machinery, and transportation equipment. The dominant corporations in these industries enjoyed enormous economies of scale because of their significant capital investments in production and distribution facilities. To cope with their larger investment base and extended range of customers, the companies needed a more elaborate organization than Smith’s pin factory to coordinate and gain the scale economies from their purchasing, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and product development activities. They also needed, of course, more managers to staff these departments and to coordinate products and processes. Figure 2-1 illustrates the centralized functional organization that evolved to manage the typical late-nineteenth-century industrial enterprise.1

In the centralized functional organization, the two largest functional departments—production and sales—performed the primary value-adding activities. A third department, finance, performed two important functions: (1) coordinating the flow of funds to and from the various operating departments and (2) providing information to senior executives so that they could monitor the operating units’ performance and allocate resources among them. The enterprise also needed departments to perform specialized activities such as purchasing, research and product development, logistics, engineering, legal, real estate, human resources, and public relations. The heads of the major functional departments, along with the president and chairman of the board, constituted the corporation’s senior decision-making team. Regular meetings of the senior executive team coordinated the activities across the corporation’s functional departments.

Figure 2-1 The Multiunit, Multifuncitonal Entreprise

Source: Albred D. Chandler Scale and Scope: the Dynamics of industrial Capitalism (cambridge , MA: Harvard University Press, 1990)

The centralized functional structure in late-nineteenth-century corporations offered considerable advantages for the enterprise. Individuals in each functional department had considerable experience and expertise in their fields. They collaborated with department colleagues to perform their assigned tasks—in production, purchasing, product development, legal, and marketing—effectively and efficiently. And the large clusters of people doing similar tasks provided excellent opportunities for coaching, mentoring, and promotion from within.

Successful industrial companies continued to grow in the early twentieth century. Some acquired competitors through horizontal combinations. Several, such as Ford Motor, undertook vertical integration to better coordinate the flow of materials into and out of factories. Most companies expanded geographically so that they could leverage their physical and organizational economies of scale in their domestic markets to reach customers in more distant markets. And many exploited their existing production and distribution infrastructure, as well as their extensive organizational and managerial capabilities, to diversify into new product lines and market segments.

So by the early twentieth century, the simple, focused, local manufacturing company familiar to Adam Smith a hundred years earlier had morphed into a giant, multiproduct, multifunctional, multiregional corporation. The management challenge was to continue to offer attractive, innovative, low-priced products to a broad customer base without collapsing from the complexity of operations that were now internalized within a single corporation.

As centralized functionally organized companies expanded and diversified, they encountered new problems. Coordination and handoffs between departments were often inefficient, costly, and time-consuming. The lack of shared information among marketing specialists and salespeople (who dealt with customers), engineers (who designed new products and services), and operating people (who built the products and provided the services) often led to expensively designed products and services that were costly to manufacture and deliver and didn’t meet customers’ expectations and needs. Functional organizations typically were also slow to respond to changes in customer preferences and new opportunities or threats in the marketplace.

Alfred Chandler summarized the problems faced by these centralized, functional organizations:

The lack of time, of information, and of psychological commitment to an overall entrepreneurial viewpoint were not necessarily serious handicaps if the company’s basic activities remained stable, that is, if its sources of raw materials and supplies, its manufacturing technology, its markets, and the nature of its products and product lines stayed relatively unchanged. But when further expansion into new functions, into new geographical areas, or into new product lines greatly increased all types of administrative decisions, then the executives in the central office became overworked and their administrative performance less efficient. These increasing pressures, in turn, created the need for the building or adoption of the multidivisional structure with its general office and autonomous operating divisions.2

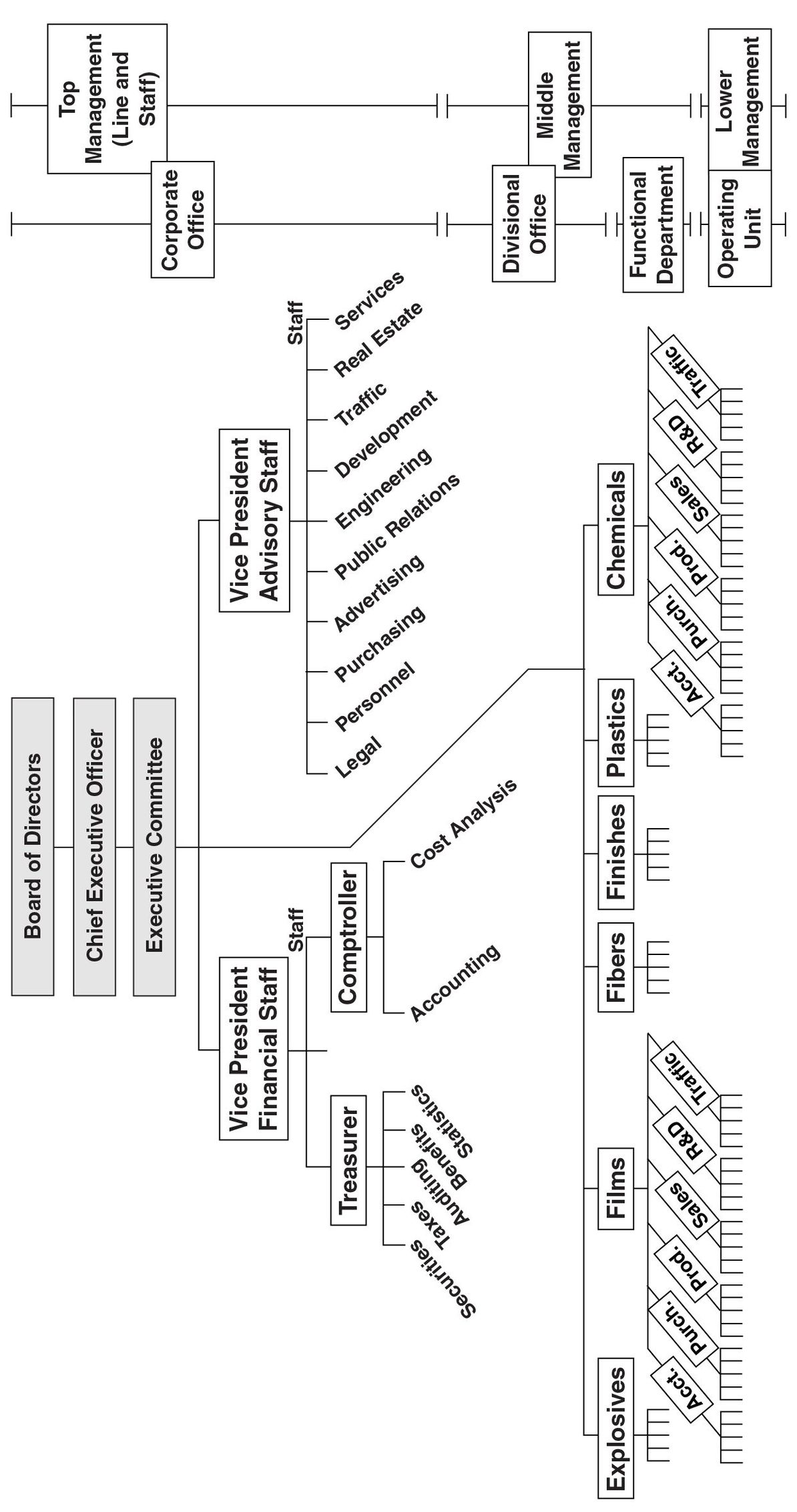

Companies such as DuPont, General Motors, General Electric, and Matsushita introduced a new organization form in the 1920s and 1930s. The multidivisional company was organized around divisions focused on specific product lines and geographic regions. Each division brought together employees with skills from all the business functions to work together to develop, build, and deliver a specific product line sold to customers in defined market segments (see Figure 2-2). A general manager headed each division, assisted by a staff that included the heads of functional activities for the division. So each product or geographic division became a replica of the original enterprise, with its own centralized functional department organization, except that the general manager was now a middle manager reporting to the senior executives in the corporate headquarters.

Executives in the corporate office no longer ran the business. Their role was to evaluate the performance of the operating divisions and do the strategic planning and resource allocation of funds, facilities, and personnel to the divisions. The corporate office also included staff who had specialized skills to support the corporate executives and who advised and coordinated the work done by their counterparts in the operating companies.

Figure 2-2 DuPont Corporation: An Example of Multidivisional (M-from) Structure

Source: Alfred D. Chandler, Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990)

The introduction of the multidivisional organization, although enabling the product and geographic divisions to be more responsive to local opportunities and threats, had its own management challenges. The smaller product divisions lost many of the efficiencies—the scale economies and learning curve effects—associated with focused, functional organizations whose resources could be shared throughout multiple product lines, market segments, and geographies. Customers became confused and often complained when multiple salespersons, from what they previously thought was a single corporate entity, called on them, each one promoting a narrow product line. Also, companies risked losing deep functional expertise when they dispersed specialists throughout the organization into the small heterogeneous groups in each operating division, rather than cluster them where they could educate and solve problems with each other in homogeneous groups.

The 1960s saw the birth of the conglomerate, a new organization form. Rather than achieve growth through expansion from core businesses, technologies, and capabilities or through acquisition in related businesses and industries, several companies grew by acquiring and merging unrelated businesses. Companies such as ITT, Litton Industries, Textron, and Gulf + Western became a collection of autonomous operating companies with no apparent synergies among them.

One apparent motivation for conglomerate growth was to reduce the risk of business cycles by investing in a diversified portfolio of businesses. This rationale, of course, was more about reducing the risk to the senior executive team, because shareholders could diversify by owning shares in a broad portfolio of companies and thereby avoid the high costs of mergers and acquisitions and the deadweight loss of a corporate office. A more plausible, economically grounded rationale was that the senior executives in these conglomerates were exceptional managers and could use their superior knowledge and skill to create more value from the collection of companies they owned than would occur if the companies operated independently without the benefit of the corporate office.

A similar organization form arose in many developing nations. Business groups, such as the Tata Group in India, the Koç Group in Turkey, Siam Cement in Thailand, and the Samsung and Hyundai chaebols in South Korea, are massive collections of unrelated businesses that operate mostly within their country of origin. These groups evolved within each country because their local governments followed an explicit policy of import substitution by erecting trade and capital barriers that limited foreign competition. The business groups, typically headed by a skilled entrepreneurial family, prospered locally by substituting for institutional gaps in their countries’ infrastructures, such as poorly functioning capital and labor markets, limited consumer information and recourse about product quality, and uncertain and frequently corrupt judicial and political environments.3

But most of the countries in which business groups developed and thrived are now joining the global economy. With their countries now open to global markets, the previously protected business groups are now subject to vigorous competition from abroad. The headquarters of these country-specific business groups must now evaluate the benefits of having hundreds of unrelated businesses operate within a single corporate structure. They must address how the executive team at the business group headquarters adds, rather than subtracts from, the value being created by its local operating companies.

Beyond the development of conglomerates and emerging market business groups, the current information- and knowledge-based global economy has created new opportunities for a corporate headquarters to create synergy. Some corporations have delivered consistently excellent performance by operating effective management systems among their business units, with all managers following similar business strategies. For example, a company like Cisco has exceptional skills for integrating technology companies procured in acquisitions. Others are effective at managing innovative product development throughout a collection of companies by following product leadership strategies. At the other extreme, some headquarters are adept at managing mature, commodity-type companies to foster continual cost reductions, process improvements, supply-chain management, and cooperative labor relations.

Several companies have become enormously successful by leveraging a well-known brand across diverse businesses. Disney movies create animal characters, such as Mickey Mouse and the Lion King, which Disney then leverages into theme parks, television programs, and consumer retail outlets. Richard Branson founded Virgin Airlines and subsequently leveraged the Virgin brand—associated with fun, high quality, excellent service, and a particular lifestyle—into businesses as diverse as trains, resorts, finance, soft drinks, music, mobile phones, cars, wines, publishing, and bridal wear.

Other corporations, such as financial services and telecommunications companies, have exploited their customer relationships to offer one-stop shopping for a wide array of services within their industry. Corporations such as Microsoft and eBay have become dominant in their sectors by leveraging an industry-standard platform into a broad array of services. Pharmaceutical and biotechnology corporations leverage their basic and applied research about specific disease categories into new drugs and treatments that enable them to dominate their sectors.

In all these examples, individual businesses are worth far more within the corporate structure than if they were operated as independent units. The key organizational question for any sizable enterprise, therefore, is how the corporate headquarters adds value to its collection of functional, product, channel, and geographical business units. For the corporate office to add value, the benefits from its monitoring, coordination, and resource allocation must exceed the cost of its operations. The corporate headquarters destroys value when it introduces delays in decision making, is not responsive to emerging local opportunities and threats, and makes errors in resource allocation and direction because of its lack of contact with local market conditions, competitors, and technologies.

If the corporate headquarters does not add value, then the market for corporate control will operate to restructure the company. The leveraged buyout (LBO) and management buyout (MBO) movement of the 1980s was a reaction that unleashed the value contained in collections of business units. Enabled by innovation in capital markets, this movement eliminated or dramatically reduced the role of corporate offices, particularly in diversified corporations, that were perceived to be destroying rather than creating shareholder value.

ALIGNING STRUCTURE WITH STRATEGY

Much of the academic as well as managerial literature on strategy focuses on business-level strategy: how a business unit positions itself and leverages its resources for competitive advantage.4 If all companies were akin to Adam Smith’s pin factory, this treatment would be sufficient. But because most companies are now a complex mixture of centralized functional and decentralized business units, corporate headquarters have tried various ways of coordinating activities and creating synergies.

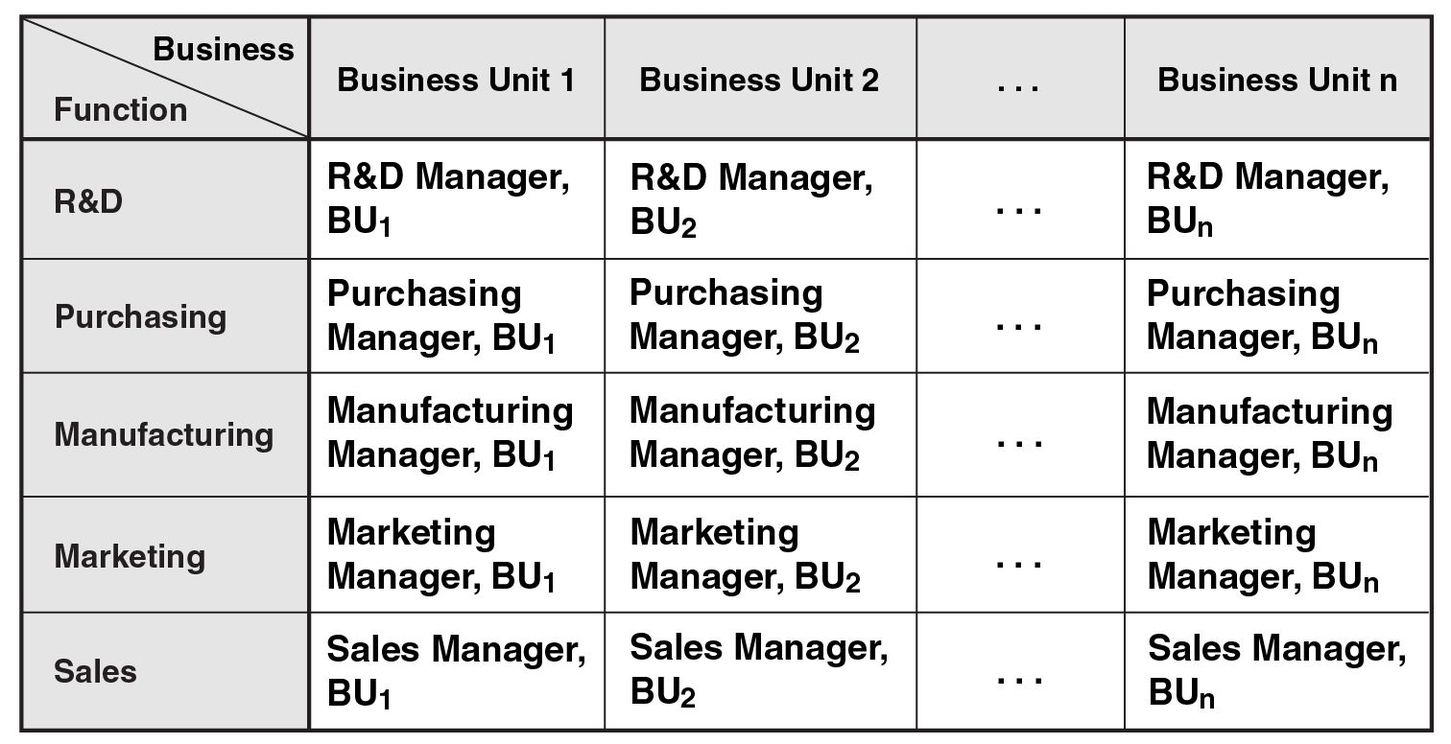

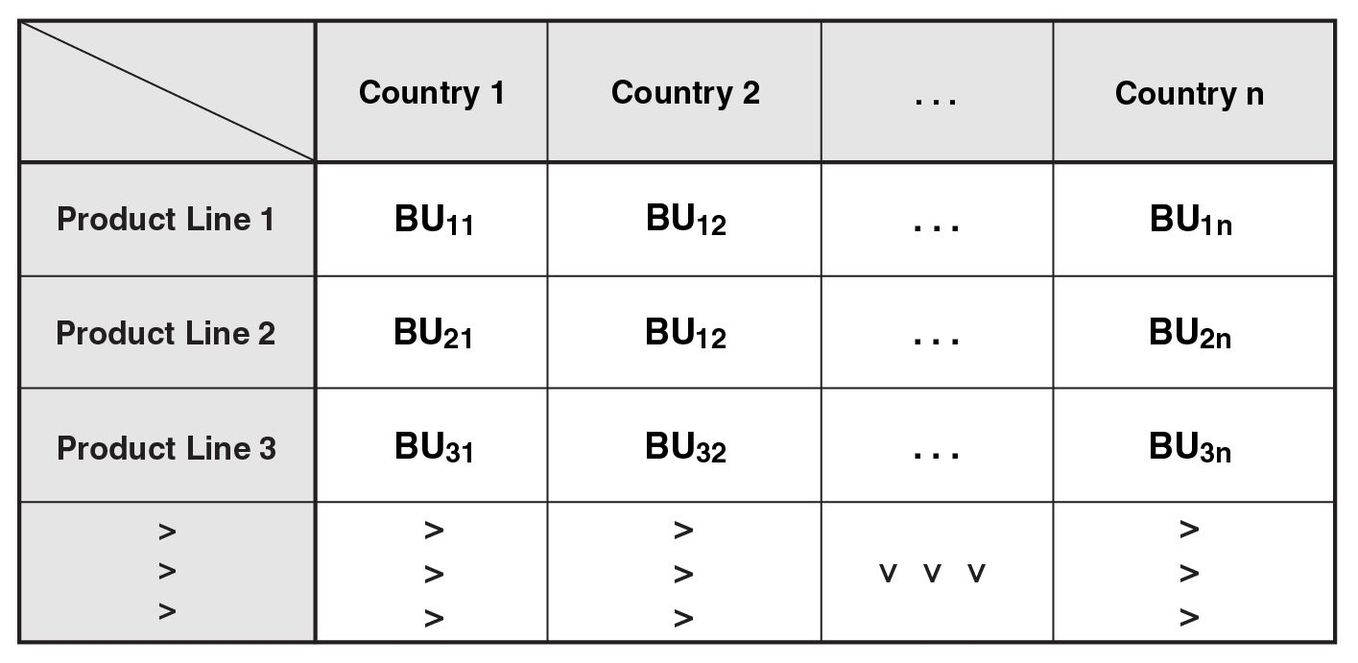

Many companies have attempted to solve the coordination problem by adopting a matrix organization.5 Figure 2-3 shows a typical matrix organization in which a manager reports both to a senior corporate functional executive and to a product or line-of-business manager. Figure 2-4 shows a matrix organization that attempts to align local operating companies with global product groups and local country managers.

Figure 2-3 The Matrix Organization

ABB, a global electrical products company, made the product line–geographical matrix approach popular in the 1990s, when it organized its hundreds of local business units around the world. In the new structure, each local business unit reported to both a country executive and a worldwide line-of-business executive. The matrix organization apparently allowed the corporation to achieve the benefits of centralized coordination, functional expertise, and economies of scale for product groups while maintaining local divisional autonomy and entrepreneurship for marketing and sales activities.

Figure 2-4 The Matrix Organization Across Global Product Groups and Countries

In practice, despite their appeal, matrix organizations have proven difficult to manage because of the inherent tension between the interests of the senior executives responsible for managing either a row or a column of the matrix. A manager stuck at a matrix intersection struggles to coordinate between the preferences of his “row” and “column” managers, leading to new sources of difficulty, conflict, and delay. The ultimate source of accountability and authority in a matrix organization remains ambiguous. Newer, so-called post-industrial forms of organization have been proposed. Examples include virtual and networked organizations that operate across traditional boundaries, and Velcro organizations, which can be snapped apart and reassembled in new structures in response to changing opportunities.6

With all the innovation in new structures, a purely organizational solution to balancing the tension between specialization and integration remains elusive. This should not be surprising. In McKinsey’s famous 7-S Model for designing aligned organizations, strategy and structure are only two of the seven S’s.7 A third S—systems—must also be mobilized to create organizational alignment. McKinsey defined systems as follows: “the formal processes and procedures used to manage the organization, including the management control systems, performance measurement and reward systems, planning, budgeting, and resource allocation systems, information systems, and distribution systems.”

McKinsey conducted its research for the 7-S Model in 1980, before the development of Strategy Maps, the Balanced Scorecard, and the five principles—mobilize, translate, align, motivate, and govern—for creating a strategy-focused organization.8 We can now see how the Balanced Scorecard innovation enables companies to design their operating systems to align structure with strategy and also to contribute to the four other S’s: staffing, skills, style, and shared values.9 The insight from our work with hundreds of organizations is that organizations should not search for the perfect structure for their strategy. Instead, they should choose a structure that is reasonable and seems to work without major conflicts, and then design a customized, cascaded system of linked Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards to tune the structure—the corporation and its collection of centralized functions and decentralized product groups and geographical units—to the strategy.

BALANCED SCORECARD: A SYSTEM FOR ALIGNING CORPORATE STRATEGY AND STRUCTURE

Chandler’s work and extensions by Michael Porter affirm that strategy precedes structure and systems. We must start, therefore, with a brief discussion of corporate strategy before illustrating how Strategy Maps and the Balanced Scorecards align organization structure with corporate-level strategy. Goold, Campbell, and Alexander argue that corporate strategy—the rationale for operating multiple businesses within the same corporate entity—must derive from the company’s “parenting advantage.”10 The corporation must demonstrate what we call the enterprise value proposition: how corporate headquarters creates more value from the businesses it owns and operates than its rivals would if they owned the same set of businesses, or if the businesses operated completely independently. 11 The four Balanced Scorecard perspectives provide a natural way to categorize the various types of enterprise value propositions that can contribute to corporate synergies:

Financial Synergies

- Effectively acquiring and integrating other companies.

- Maintaining excellent monitoring and governance processes across diverse enterprises.

- Leveraging a common brand (Disney, Virgin) across multiple business units.

- Achieving scale or specialized skills in negotiations with external entities such as governments, unions, capital providers, and suppliers.

Customer Synergies

- Consistently delivering a common value proposition across a geographically dispersed network of retail or wholesale outlets.

- Leveraging common customers by combining products or services from multiple units to provide distinct advantages: low cost, convenience, or customized solutions.

Business Process Synergies

- Exploiting core competencies that leverage excellence in product or process technologies across multiple business units.12 Consider competencies in microelectronics fabrication, optoelectronics, software development, new product development, and just-in-time production and distribution systems that lead to competitive advantage in multiple industry segments. Core competencies can also include knowledge in how to operate effectively in particular regions of the world.

- Achieving economies of scale through shared manufacturing, research, distribution, or marketing resources.

Learning and Growth Synergies

- Enhancing human capital through excellent HR recruiting, training, and leadership development practices across multiple business units.

- Leveraging a common technology, such as an industry-leading platform or channel for customers to access a wide set of company services, that is shared across multiple product and service divisions.

- Sharing best-practice capabilities through knowledge management that transfers process quality excellence across multiple business units.

Collis and Montgomery summarize such effective corporate strategies:13

An outstanding corporate strategy is not a random collection of individual building blocks but a carefully constructed system of interdependent parts . . . [I]n a great corporate strategy, all of the elements [resources, businesses, and organization] are aligned with one another. That alignment is driven by the nature of the firm’s resources—its special assets, skills and capabilities.14

Strategy Maps and the Balanced Scorecard turn out to be ideal mechanisms to describe enterprise value propositions and subsequently to align enterprise resources for superior value creation. The headquarters executive team uses its corporate Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard to articulate the theory of the enterprise: how the enterprise generates additional value by having business units operate within its hierarchical structure rather than have each unit operate as an independent entity, with its own governance structure and source of financing.

NOTES

This brief summary of a complex history is drawn from Chapter 2, “Scale, Scope, and Organizational Capabilities,” in A. D. Chandler Jr., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 14–49.

A. D. Chandler Jr., Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962), 297.

T. Khanna and K. Palepu, “Why Focused Strategies May Be Wrong for Emerging Markets,” Harvard Business Review (July–August 1997): 41–51.

We explored the role of Strategy Maps and Balanced Scorecards in describing and implementing business unit strategy in the book Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

S. Davis and P. Lawrence, “Problems of Matrix Organizations,” Harvard Business Review (May–June 1978); H. Kolodny, “Managing in a Matrix,” Business Horizons (March–April 1981).

L. Hirschhorn and T. Gilmore, “The New Boundaries of the ‘Boundaryless’ Company,” Harvard Business Review (May–June 1992); M. Raynor and J. Bower, “Lead from the Center: How to Manage Divisions Dynamically,” Harvard Business Review (May 2001); J. Bower, “Building the Velcro Organization: Creating Value Through Integration and Maintaining Organization-Wide Efficiency,” Ivey Business Journal (November–December 2003): 1–10.

R. H. Waterman, T. J. Peters, and J. R. Phillips, “Structure Is Not Organization,” Business Horizons (1980).

R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

R. S. Kaplan, “The Balanced Scorecard: Enhancing the McKinsey 7-S Model,” Balanced Scorecard Report (March 2005).

D. Collis and C. Montgomery, Corporate Strategy: Resources and the Scope of the Firm (Chicago: Irwin, 1997), refer to essentially the same concept as the “corporate advantage.” We will use the more vivid image of the corporate as parent to its various offspring.

M. Goold, A. Campbell, and M. Alexander, Corporate-Level Strategy: Creating Value in the Multibusiness Company (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994); A. Campbell, M. Goold, and M. Alexander, “Corporate Strategy: The Quest for Parenting Advantage,” Harvard Business Review (March–April 1995): 120–132.

Core competencies has been defined by Markides as the “pool of experience, knowledge and systems within the corporation that can be deployed to reduce the cost or time to create or extend a strategic asset”; strategic assets are the “imperfectly imitable, imperfectly substitutable, and imperfectly tradable assets that promote cost advantage or differentiation.” See C. Markides, “Corporate Strategy: The Role of the Centre,” in Handbook of Strategy and Management, 1st edition, eds. A. Pettigrew, H. Thomas, and R. Whittington (London: Sage Publications, 2001).

D. J. Collis and C. A. Montgomery, “Competing on Resources: Strategy in the 1990s,” Harvard Business Review (July–August 1995): 118–128; and “Creating Corporate Advantage,” Harvard Business Review (May–June 1998): 70–83.

Collis and Montgomery, “Creating Corporate Advantage,” 72.