Chapter 1. Access as a Development Tool

IN THIS CHAPTER

- Why This Chapter Is Important

- What Types of Applications Can You Develop in Access?

- Access as a Scalable Product

- What Exactly Is a Database?

- Getting to Know the Database Objects

- Object Naming Conventions

- Hardware Requirements

- How Do I Get Started Developing an Access Application?

- What’s New in Access 2007?

- Other New Features Found in Access 2007

- Additional Tips and Tricks

- Practical Examples: The Application Design for a Computer Consulting Firm

Why This Chapter Is Important

In talking to users and developers, I find that Access is a very misunderstood product. Many people think that it is just a toy for managers or secretaries wanting to play with data. Others feel that it is a serious developer product intended for no one but experienced application developers. This chapter dispels the myths of Access. It helps you decipher what Access is and what it isn’t. After reading the chapter, you will know when Access is the tool for you, and when it makes sense to explore other products.

What Types of Applications Can You Develop in Access?

I often find myself explaining exactly what types of applications you can build with Microsoft Access. Access offers a variety of features for different database needs. You can use it to develop six general types of applications:

- Personal applications

- Small business applications

- Departmental applications

- Corporationwide applications

- As a front end for enterprisewide client/server applications

- Intranet/Internet applications

Access as a Development Platform for Personal Applications

At its most basic level, you can use Access to develop simple personal database-management systems. I caution people against this idea, though. People who buy Access hoping to automate everything from their wine collections to their home finances are often disappointed. The problem is that Access is deceptively easy to use. Its wonderful built-in wizards make Access look like a product that anyone can use. After answering a series of questions, you have finished application switchboards, data entry screens, reports, and the underlying tables that support them. In fact, when Microsoft first released Access, many people asked whether I was concerned that my business as a computer programmer and trainer would diminish because Access seemed to let absolutely anyone write a database application. Although it’s true that you can produce the simplest of Access applications without any thought of design and without writing a single line of code, most applications require at least some designing and custom code.

As long as you’re satisfied with a wizard-generated personal application with only minor modifications, no problems should occur. It’s when you want to substantially customize a personal application that problems can happen.

Access as a Development Platform for Small Business Applications

Access is an excellent platform for developing an application that can run a small business. Its wizards let developers quickly and easily build the application’s foundation. The ability to build code modules enables developers to create code libraries of reusable functions, and the ability to add code behind forms and reports enables them to create powerful custom forms and reports.

The main limitation of using Access for developing a custom small business application is the time and money involved in the development process. Many people use Access wizards to begin the development process but find they need to customize their application in ways they can’t accomplish on their own. Small business owners often experience this problem on an even greater scale. The demands of a small business application are usually much higher than those of a personal application. Many doctors, attorneys, and other professionals have called me in after they reached a dead end in the development process. They’re always dismayed at how much money it will cost to make their application usable.

Access as a Development Platform for Departmental Applications

Access is perfect for developing applications for departments in large corporations. It’s relatively easy to upgrade departmental users to the appropriate hardware; for example, it’s much easier to buy additional RAM for 15 users than it is for 4,000! Furthermore, Access’s performance is adequate for most departmental applications without the need for client/server technology. Finally, most departments in large corporations have the development budgets to produce well-designed applications.

Fortunately, most departments usually have a PC guru who is more than happy to help design forms and reports. This gives the department a sense of ownership because they have contributed to the development of their application. It also makes my life as a developer much easier. I can focus on the hard-core development issues, leaving some of the form and report design tasks to the local talent.

Access as a Development Platform for Corporationwide Applications

Although Access might be best suited for departmental applications, you can also use it to produce applications that you distribute throughout the organization. How successful this endeavor is depends on the corporation. There’s a limit to the number of users that can concurrently share an Access application while maintaining acceptable performance, and there’s also a limit to the number of records that each table can contain without a significant performance drop. These numbers vary depending on factors such as the following:

- How much traffic already exists on the network?

- How much RAM and how many processors does the server have?

- How is the server already being used? For example, are applications such as Microsoft Office being loaded from the server or from local workstations?

- What types of tasks are the users of the application performing? Are they querying, entering data, running reports, and so on?

- Where are Access and your Access application run from, the server or the workstation?

- What network operating system is in place?

My general rule of thumb for an Access application that’s not client/server-based is that poor performance generally results with more than 10–15 concurrent users and more than 100,000 records. Remember, these numbers vary immensely depending on the factors mentioned, as well as on the definition of acceptable performance by you and your users. The basics of when to move to a client/server database are covered in Chapter 22, “Developing Multiuser and Enterprise Applications.” I cover additional details about this topic in a separate book, Alison Balter’s Mastering Access 2002 Client/Server Development, also published by Sams.

Developers often misunderstand what Access is and what it isn’t when it comes to being a client/server database platform. People often ask me, “Isn’t Access a ‘client/server’ database?” The answer is that Access is an unusual product because it’s a file server application out of the box, but it can act as a front end to a client/server database. In case you’re lost, here’s an explanation: If you buy Access and develop an application that stores the data on a file server in an Access database, the workstation performs all data processing. This means that every time the user runs a query or report, the file server returns all the data to the workstation. The workstation machine then runs the query and displays the results in a datasheet or on a report. This process generates a significant amount of network traffic, particularly if multiple users are running reports and queries at the same time on large Access tables. In fact, such operations can bring the entire network to a crawl.

Access as a Front End for Enterprisewide Client/Server Applications

A client/server database, such as Microsoft SQL Server or Oracle, processes queries on the server machine and returns results to the workstation. The server software itself can’t display data to the user, so this is where Access comes to the rescue. Acting as a front end, Access can display the data retrieved from the database server in reports, datasheets, or forms. If the user updates the data in an Access form, the workstation sends the update to the back-end database. You can accomplish this process either by linking to these external databases so that they appear to both you and the user as Access tables, or by using techniques that access client/server data directly.

Because Access 2007 ships with an integrated data store (the SQL Server 2005 Express Database Engine), you can develop a client/server application on the desktop and then easily deploy it to an enterprise SQL Server database. Chapter 22 briefly covers the alternatives and techniques for developing client/server applications. Alison Balter’s Mastering Access 2002 Client/Server Development provides details on how to develop Access projects.

When you reduce the volume of network traffic by moving the processing of queries to the back end, Access becomes a much more powerful development solution. It can handle huge volumes of data and a large number of concurrent users. The main issues usually faced by developers who want to deploy such a wide-scale Access application are the following:

- The variety of operating systems used by each user

- Difficulties with deployment

- The method by which each user is connected to the application and data

- The type of hardware each user has

Although processing of queries in a client/server application is done at the server, which significantly reduces network traffic, the application itself still must reside in the memory of each user’s PC. This means that each client machine must be capable of running the appropriate operating system and the correct version of Access. Even when the correct operating system and version of Access are in place, your problems are not over. Dynamic link library (DLL) conflicts often result in difficult-to-diagnose errors and idiosyncrasies in an Access application. Furthermore, Access is not the best solution for disconnected users who must access an application and its data over the Internet. Finally, Access 2007 is hardware hungry! The hardware requirements for an Access application are covered later in this chapter. The bottom line is that, before you decide to deploy a wide-scale Access application, you need to know the hardware and software configurations of all your system’s users. You must also decide whether the desktop support required for the typical Access application is feasible given the number of people who will use the system that you are building.

Access as a Development Platform for Intranet/Internet Applications

Using data access pages, you can publish your database objects as static or dynamic HTML pages. Static pages are standard HTML you can view in any browser. Access 2000 introduced the capability to create XML data and schema documents from Jet or SQL Server structures and data. You can also import data and data structures into Access from XML documents. You can accomplish this either using code or via the user interface.

Note

This book provides coverage of Internet-related features, such as working with HTML and XML files.

Access as a Scalable Product

One of Access’s biggest strong points is its scalability. You can scale an application that begins as a small business application running on a standalone machine to an enterprisewide client/server application. If you design your application properly, you can accomplish the scaling process with little to no rewriting of your application. This feature makes Access an excellent choice for growing businesses, as well as for applications you are testing at a departmental level with the idea that you might eventually distribute them corporationwide.

The great thing about Access is that, even acting as both the front end and back end with data stored on a file server in Access tables, it provides excellent security and the capability to establish database rules previously available only on back-end databases. You can apply referential integrity rules at the database level, ensuring that, for example, users do not enter orders for customers who don’t exist. You can enforce data validation rules at either a field or record level, maintaining the integrity of the data in your database. In other words, many of the features previously available only on high-end database servers are now available by using Access’s own proprietary data storage format.

What Exactly Is a Database?

The term database means different things to different people. For many years, in the world of xBase (dBASE, FoxPro, CA-Clipper), database was used to describe a collection of fields and records. (Access refers to this type of collection as a table.) In a client/server environment, database refers to all the data, schema, indexes, rules, triggers, and stored procedures associated with a system. In Access terms, a database is a collection of all the tables, queries, forms, data access pages, reports, macros, and modules that compose a complete system.

Getting to Know the Database Objects

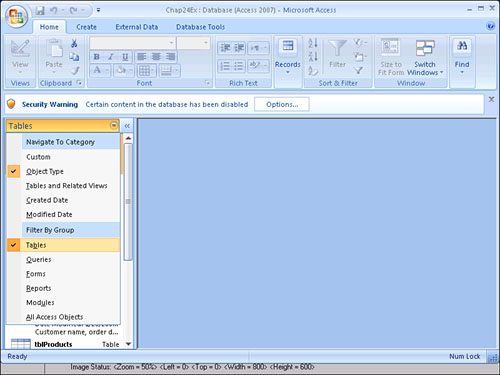

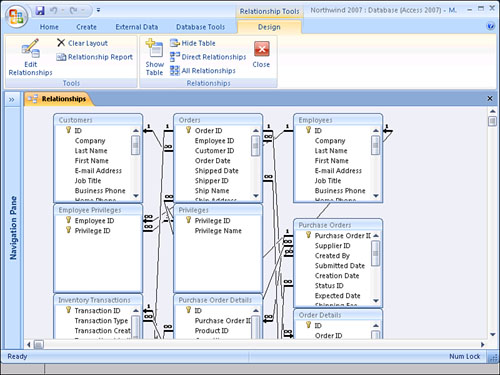

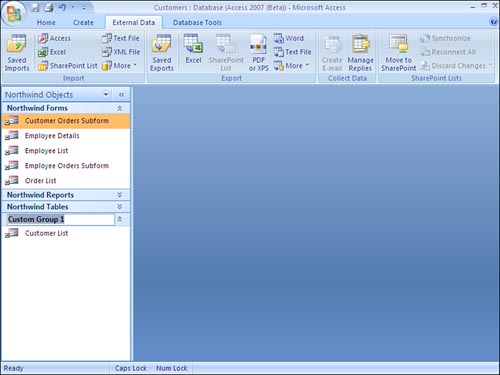

As mentioned previously, tables, queries, forms, reports, macros, and modules combine to comprise an Access database. Each of these objects has a special function. An Access application also includes several miscellaneous objects, including relationships, database properties, and import/export specifications. With these objects, you can create a powerful, user-friendly, integrated application. Figure 1.1 shows the Access application window. Notice the categories of objects listed in the Navigation Pane. The following sections take you on a tour of the objects that make up an Access database.

Figure 1.1. The Navigation Pane displays categories for each type of database object.

Tables: A Repository for Your Data

Tables are the starting point for your application. Whether your data is stored in an Access database or you are referencing external data by using linked tables, all the other objects in your database either directly or indirectly reference your tables.

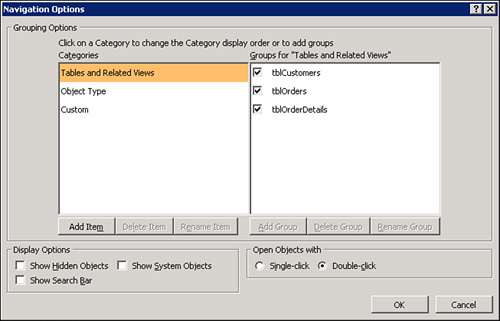

To view all the tables that are contained in the open database, select Tables from the Navigation Pane drop-down, as shown in Figure 1.2. (Note that you won’t see any hidden tables unless you have checked the Hidden Objects check box in the Navigation Options dialog box, as shown in Figure 1.3.) If you want to view the data in a table, double-click the name of the table you want to view.

Figure 1.2. To view all tables, select Tables from the Navigation Pane drop-down.

Figure 1.3. The Navigation Options dialog box allows you to show hidden tables.

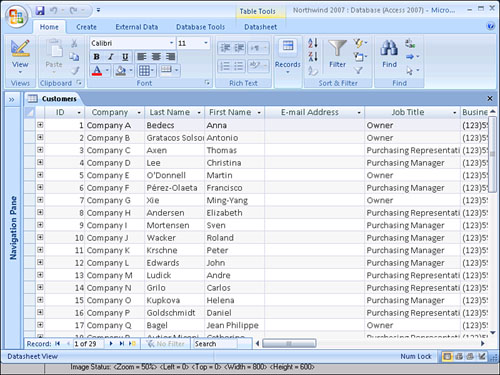

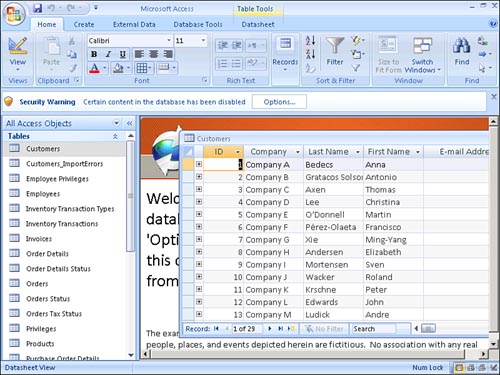

Access displays the table’s data in a datasheet, which includes all the table’s fields and records (see Figure 1.4). Note that I have collapsed the Navigation Pane so that you get a better view of the table (described later in this chapter). You can modify many of the datasheet’s attributes and even search for and filter data from within the datasheet. If the table is related to another table (such as the Northwind Customers and Orders tables), you can also expand and collapse the subdatasheet to view data stored in child tables. This book does not cover these techniques. You can find them in the Access user manual or any introductory Access book, such as Sams Teach Yourself Microsoft Office Access 2007 in 24 Hours.

Figure 1.4. The Datasheet view of the Customers table in the Northwind database includes all the table’s fields and records.

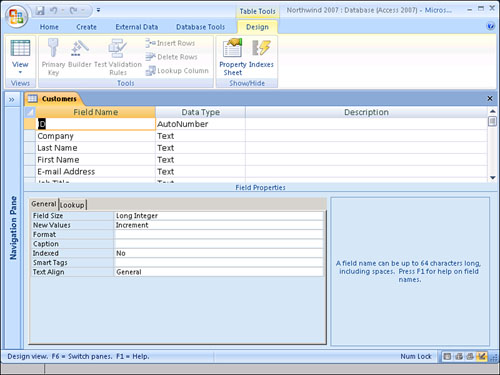

As a developer, you most often want to view the table’s design, which is the blueprint or template for the table. To view a table’s design, click the View icon on the home page of the ribbon while the table is open (see Figure 1.5). In Design view, you can view or modify all the field names, data types, and field and table properties. Access gives you the power and flexibility you need to customize the design of your tables. Chapter 2, “What Every Developer Needs to Know About Databases and Tables,” covers these topics.

Figure 1.5. The design of the Customers table is the blueprint or template for the table.

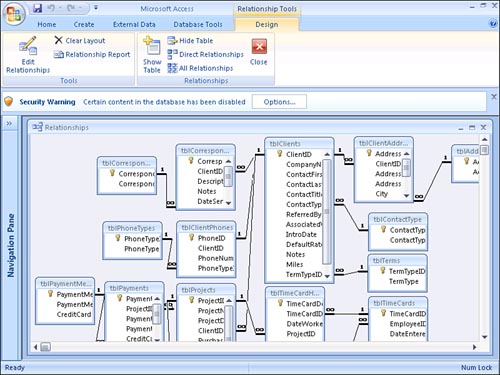

Relationships: Tying the Tables Together

To properly maintain your data’s integrity and ease the process of working with other objects in the database, you must define relationships among the tables in your database. You accomplish this by using the Relationships window. To view the Relationships window, click to select the Database Tools tab. Then select the Relationships button in the Show/Hide group. The Relationships window appears, as shown in Figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6. The Relationships window is the place where you view and maintain the relationships in the database.

In this window, you can view and maintain the relationships in the database. If you or a fellow developer has set up some relationships, but you don’t see any in the Relationships window, select the All Relationships button in the Relationships group on the Design tab to unhide any hidden tables and relationships.

Notice that many of the relationships in Figure 1.6 have a join line between tables with a number 1 and an infinity symbol (∞). This indicates a one-to-many relationship between the tables. If you double-click the join line, the Edit Relationships dialog box opens (see Figure 1.7). In this dialog box, you can specify the exact nature of the relationship between tables. The relationship between Customers and Orders, for example, is a one-to-many relationship with referential integrity enforced. This means that the user cannot add orders for customers who don’t exist. Notice that the check box to Cascade Update Related Fields is not checked. This means that the user cannot update the CustomerID of a customer in the Customers table. Because Cascade Delete Related Records is not checked, the user cannot delete customers from the Customers table if they have corresponding orders in the Orders table.

Figure 1.7. The Edit Relationships dialog box lets you specify the nature of the relationship between tables.

Chapter 3, “Relationships: Your Key to Data Integrity,” extensively covers the process of defining and maintaining relationships. It also covers the basics of relational database design. For now, remember that you should establish relationships both conceptually and literally as early in the design process as possible. They are integral to successfully designing and implementing your application.

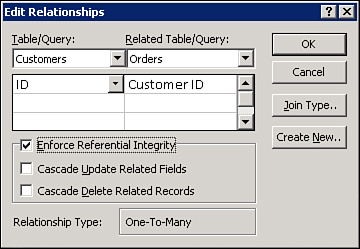

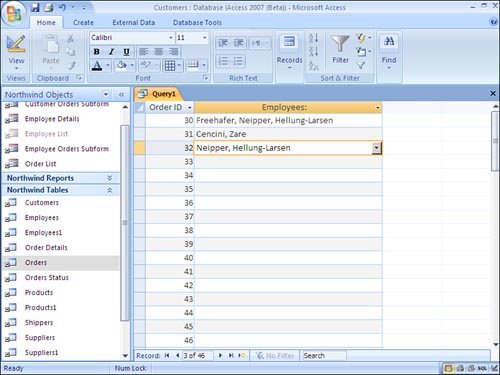

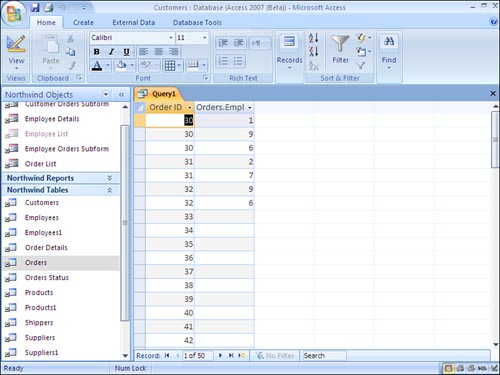

Queries: Stored Questions or Actions You Apply to Your Data

Queries in Access are powerful and multifaceted. Select queries enable you to view, summarize, and perform calculations on the data in your tables. Action queries let you add to, update, and delete table data. To run a query, select Queries from the Navigation drop-down and then double-click the query you want to run, or right-click to select the query you want to run and then click Open. When you run a select query, a datasheet appears, containing all the fields specified in the query and all the records meeting the query’s criteria (see Figure 1.8). When you run an action query, Access runs the specified action, such as making a new table or appending data to an existing table. In general, you can update the data in a query result because the result of a query is actually a dynamic set of records, called a dynaset, based on your tables’ data.

Figure 1.8. When you run the Inventory on Order query, a datasheet appears, containing all the fields specified in the query and all the records meeting the query’s criteria.

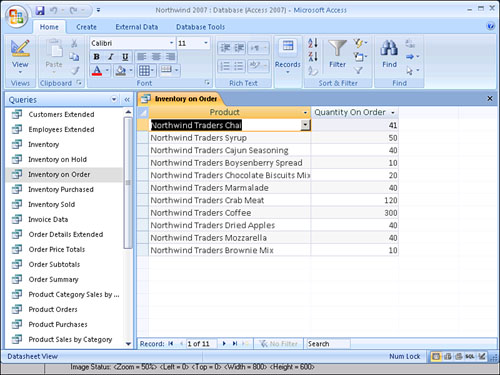

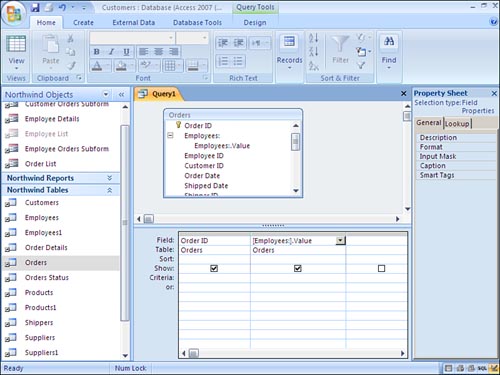

When you store a query, only its definition, layout or formatting properties, and datasheet are actually stored in the database. Access offers an intuitive, user-friendly tool for you to design your queries. Figure 1.9 shows the Query Design window. To open this window, select Queries from the Navigation pane drop-down, choose the query you want to modify, and right-click and select Design. The query pictured in the figure selects data from Purchase Orders, Purchase Orders Status, and Purchase Price Totals tables and queries. (Note that you can base queries on tables and on other queries.) It displays the Creation Date, Supplier ID, Shipping Fee, Taxes, and several other fields from the Purchase Orders table, the Status from the Purchase Order Status table, and the Sub Total expression from the Purchase Price Totals query. Chapter 4, “What Every Developer Needs to Know About Query Basics,” and Chapter 12, “Advanced Query Techniques,” both cover queries. Because queries are the foundation for most forms and reports, I cover them throughout this book as they apply to other objects in the database.

Figure 1.9. The design of this query displays data from the Purchase Orders and Purchase Order Status tables and the Purchase Price Totals query.

Forms: A Means of Displaying, Modifying, and Adding Data

Although you can enter and modify data in a table’s Datasheet view, you can’t control the user’s actions very well; likewise, you can’t do much to facilitate the data entry process. This is where forms come in. Access forms can take on many traits, and they’re very flexible and powerful.

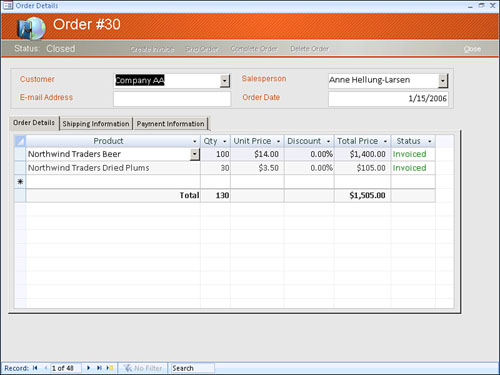

To view any form, select Forms from the Navigation Pane. Then double-click the form you want to view, or right-click the form you want to view and click Open. Figure 1.10 illustrates a form in Form view. This form is actually four forms in one: one main form and three subforms. The main form displays information from the Orders table, and the subforms display information from the Order Details table and the Orders table. As the user moves from order to order, the form displays the orders details associated with that order. When the user clicks to select the Shipping Information and Payment Information tabs, she can see additional information about that order.

Figure 1.10. The Order Details form includes customer, order, and order detail information.

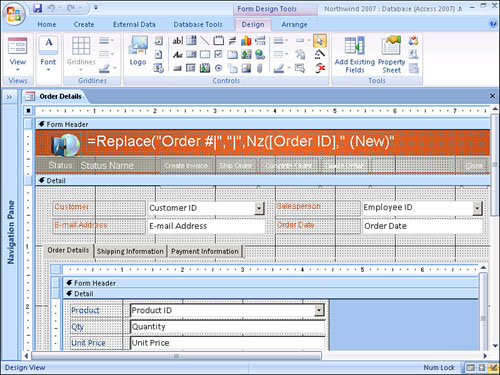

As with tables and queries, you can also view forms in Design view. To view the design of a form, right-click the Form from within the Navigation Pane and select Design. Figure 1.11 shows the Order Details form in Design view. Notice the three subforms within the main form. Chapter 5, “What Every Developer Needs to Know About Forms,” and Chapter 10, “Advanced Form Techniques,” officially cover forms. I also cover forms throughout this text as they apply to other examples of building an application.

Figure 1.11. The design of the Order Details form shows three subforms.

Reports: Turning Data into Information

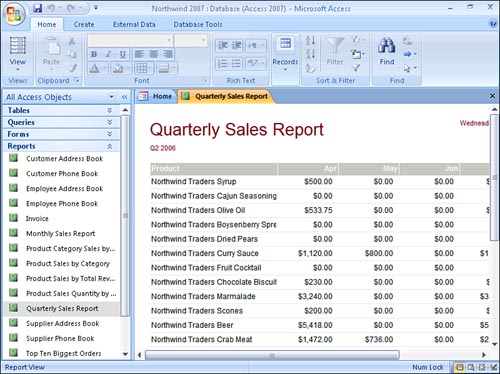

Forms enable you to enter and edit information, but with reports, you can display information, usually to a printer. Figure 1.12 shows a report in preview mode. To preview any report, right-click the report in the Navigation Pane and select Print Preview, or double-click the report you want to preview. Notice the colors in the report, as well as other details, such as the shaded area for the column headings. Like forms, reports can be elaborate and exciting, yet can contain valuable information.

Figure 1.12. This preview of the Quarterly Sales Report displays information in the report.

If you haven’t guessed yet, you can view reports in Design view, as shown in Figure 1.11. To view the design of any report, right-click the report in the Navigation Pane and select Design View. Figure 1.12 illustrates a report with many sections; in the figure you can see a Report Header, Page Header, Detail section, Page Footer, and Report Footer—just a few of the many sections available on a report. Just as a form can contain subforms, a report can contain subreports. Chapter 6, “What Every Developer Needs to Know About Reports,” and Chapter 11, “Advanced Report Techniques,” cover reports. I also cover them throughout the book as they apply to other examples.

Macros: A Means of Automating Your System

Macros in Access aren’t like the macros in other Office products. You can’t record them, as you can in Microsoft Word or Excel, and Access does not save them as Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) code. With Access macros, you can perform most of the tasks that you can manually perform from the keyboard, menus, and toolbars. Macros enable you to build logic into your application flow.

Available in Microsoft Office Access 2007 are embedded macros. Instead of appearing in the Navigation Pane as a separate object, an embedded macro is part of the object to which it is associated. When you modify an embedded macro, it does not affect any other macros or objects in the database. Because you can prevent embedded macros from performing certain potentially unsafe operations, they are trusted. (Macros, including embedded macros, are covered in Chapter 7, “What Are Macros, and When Do You Need Them?”)

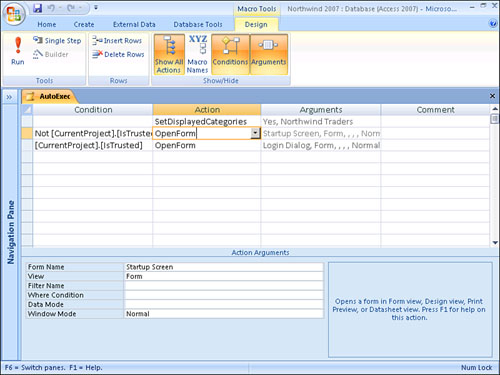

To run a macro, select Macros from the Navigation Pane, right-click the macro you want to run, and then click Run. Access then executes the actions in the macro. To view a macro’s design, right-click the macro in the Navigation Pane and select Design View. The macro pictured in Figure 1.13 has four columns. The first column enables you to specify a condition. The action in the macro’s second column won’t execute unless the condition for that action evaluates to True. The third column shows you the arguments for that line of the macro, and the fourth column lets you document the macro. In the bottom half of the Macro Design window, you specify the arguments that apply to the selected action. In Figure 1.13, the selected action is OpenForm, which accepts six arguments: Form Name, View, Filter Name, Where Condition, Data Mode, and WindowMode.

Figure 1.13. The design of the AutoExec macro contains conditions, actions, arguments, and comments.

Modules: The Foundation to the Application Development Process

Modules, the foundation of any application, let you create libraries of functions that you can use throughout your application. You usually include subroutines and functions in the modules that you build. Functions always return a value; subroutines do not. By using code modules, you can do the following:

- Perform error handling

- Declare and use variables

- Loop through and manipulate recordsets

- Call Windows API and other library functions

- Create and modify system objects, such as tables and queries

- Perform transaction processing

- Perform many functions not available with macros

- Test and debug complex processes

- Create library databases

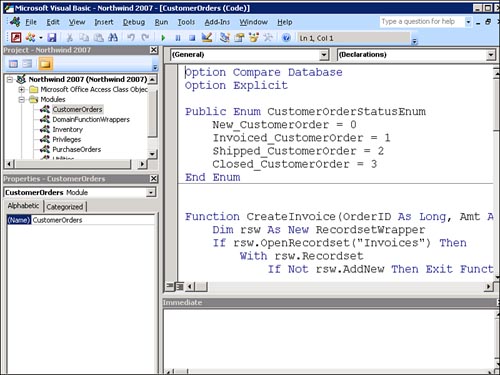

These are just a few of the tasks you can accomplish with modules. To view the design of an existing module, right-click the module you want to modify in the Navigation Pane and click Design View to open the Module Design window (see Figure 1.14). The global code module in Figure 1.14 contains a General Declarations section and five functions. The function that is visible is called CreateInvoice. Chapter 8, “VBA: An Introduction,” and Chapter 13, “Advanced VBA Techniques,” discuss modules and VBA, respectively. I also cover modules and VBA extensively throughout this book.

Figure 1.14. The global code module in Design view shows the General Declarations section and CreateInvoice function.

Object Naming Conventions

Finding a set of naming conventions—and sticking to it—is one of the keys to successful development in Access or any other programming language. When you’re choosing a set of naming conventions, look for three characteristics:

- Ease of use

- Readability

- Acceptance in the developer community

The naming conventions that I use in this book were derived from the Leszynski/Reddick naming conventions that were prominent in Access versions 1.x and 2.0. These standards were adopted and used extensively by the development community and can be found in most good development books and magazine articles written in the past few years. These conventions give you an easy-to-use, consistent methodology for naming the objects in all these environments.

Appendix A, “Naming Conventions,” is available for download at www.samspublishing.com and includes a summarized version of the conventions for naming objects. I’ll be using them throughout the book and highlighting certain aspects of them as they apply to each chapter.

Hardware Requirements

One of the downsides of Access is the number of hardware resources it requires. The requirements for a developer are different from those for an end user, so I have broken the system requirements into two parts. As you read through these requirements, be sure to note actual versus recommended requirements.

What Hardware Does Microsoft Office Access 2007 Require?

According to Microsoft documentation, these are the official minimum requirements to run Microsoft Access 2007:

- 500 megahertz (MHz) processor or higher

- Windows XP with Service Pack 2, Windows 2003 with Service Pack 1, or a later operating system, such as Windows Vista.

- 256 megabytes (MB) RAM or higher

- 1.5 gigabytes (GB) of hard disk space (some will be freed after the original download package is removed from the hard drive

- 1024x768 or higher resolution

- CD-ROM or DVD drive

- A pointing device

The bottom line for hardware is the more, the better. You just can’t have enough memory or hard drive capacity. The more you have, the happier you will be using Access.

How Do I Get Started Developing an Access Application?

Many developers believe that because Access is such a rapid application development environment, there’s absolutely no need for system analysis or design when creating an application. I couldn’t disagree more. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, Access applications are deceptively easy to create, but without proper planning, they can become a disaster.

Task Analysis

The first step in the development process is task analysis, or considering each and every process that occurs during the user’s workday—a cumbersome but necessary task. When I started working for a large corporation as a mainframe programmer, I was required to carefully follow a task analysis checklist. I had to find out what each user of the system did to complete her daily tasks, document each procedure, determine the flow of each task to the next, relate each task of each user to her other tasks as well as to the tasks of every other user of the system, and tie each task to corporate objectives. In this day and age of rapid application development and changing technology, task analysis in the development process seems to have gone out the window. I maintain that if you don’t take the required care to complete this process at least at some level, you will have to rewrite large parts of the application.

Data Analysis and Design

After you have analyzed and documented all the tasks involved in the system, you’re ready to work on the data analysis and design phase of your application. In this phase, you must identify each piece of information needed to complete each task. You must assign these data elements to subjects, and each subject will become a separate table in your database. For example, a subject might be a client; every data element relating to that client—the name, address, phone, credit limit, and any other pertinent information—would become fields within the client table.

You should determine the following for each data element:

- Appropriate data type

- Required size

- Validation rules

You should also determine whether you will allow the user to update each data element and whether it’s entered or calculated; then you can figure out whether you have properly normalized your table structures.

Normalization Made Easy

Normalization is a fancy term for the process of testing your table design against a series of rules that ensure that your application will operate as efficiently as possible. These rules are based on set theory and were originally proposed by Dr. E. F. Codd. Although you could spend years studying normalization, its main objective is an application that runs efficiently with as little data manipulation and coding as possible. Chapter 3 covers normalization and database design in detail. For now, here are six of the basic normalization rules:

- Fields should be atomic—that is, each piece of data should be broken down as much as possible. For example, instead of creating a field called

Name, you would create two fields: one for the first name and the other for the last name. This method makes the data much easier to work with. If you need to sort or search by first name separately from the last name, for example, you can do so without extra effort. - Each record should contain a unique identifier so that you have a way of safely identifying the record. For example, if you’re changing customer information, you can make sure you’re changing the information associated with the correct customer. We refer to this unique identifier as a primary key.

- The primary key is a field or fields that uniquely identify the record. Sometimes you can assign a natural primary key. For example, the Social Security number in an employee table should serve to uniquely identify that employee to the system. At other times, you might need to create a primary key. Because two customers could have the same name, for example, the customer name might not uniquely identify the customer to the system. You might need to create a field that would contain a unique identifier for the customer, such as a customer ID.

- A primary key should be short, stable, and simple. Short means it should be small (not a 50-character field). A Long Integer is perfect as a primary key. Stable means the primary key should be a field whose value rarely, if ever, changes. For example, although a customer ID would rarely change, a company name is much more likely to change. Simple means it should be easy for a user to work with.

- Every field in a table should supply additional information about the record that the primary key serves to identify. For example, every field in the customer table describes the customer with a particular customer ID.

- Information in the table shouldn’t appear in more than one place. For example, a particular customer name shouldn’t appear in more than one record.

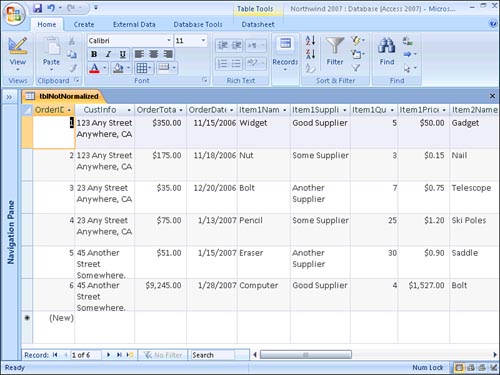

Take a look at an example. The datasheet shown in Figure 1.15 is an example of a table that hasn’t been normalized. Notice that the CustInfo field is repeated for each order, so if the customer address changes, it has to be changed in every order assigned to that customer. In other words, the CustInfo field is not atomic. If you want to sort by city, you’re out of luck, because the city is in the middle of the CustInfo field. If the name of an inventory item changes, you need to make the change in every record where that inventory item was ordered. Probably the worst problem in this example involves items ordered. With this design, you must create four fields for each item the customer orders: name, supplier, quantity, and price. This design would make it extremely difficult to build sales reports and other reports your users need to effectively run the business.

Figure 1.15. This table hasn’t been normalized.

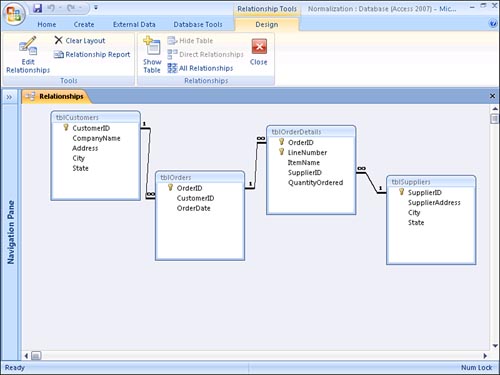

Figure 1.16 shows the same data normalized. Notice that I’ve broken it out into several different tables: tblCustomers, tblOrders, tblOrderDetails, and tblSuppliers. The tblCustomers table contains data that relates only to a specific customer.

Figure 1.16. The data has been normalized into four separate tables.

I have uniquely identified each record by a contrived CustID field, which I use to relate the orders table, tblOrders, to tblCustomers. The tblOrders table contains only information that applies to the entire order, rather than to a particular item that the customer ordered. This table contains the CustID of the customer who placed the order and the date of the order, and I’ve related it to the tblOrderDetails table based on the OrderID. The tblOrderDetails table holds information about each item ordered for a particular OrderID.

There’s no limit to the potential number of items that the user can place on an order. The user can add as many items to the order as needed, simply by adding more records to the tblOrderDetails table. Finally, I placed the supplier information in a separate table, tblSuppliers, so that if any of the supplier information changes, the user has to change it in only one place.

Prototyping

Although the task analysis and data analysis phases of application development haven’t changed much since the days of mainframes, the prototyping phase has changed. In working with mainframes or DOS-based languages, it was important to develop detailed specifications for each screen and report. I remember requiring users to sign off on every screen and report. Even a change such as moving a field on a screen meant a change order and approval for additional hours. After the user signed off on the screen and report specifications, the programmers would go off for days and work arduously to develop each screen and report. They would return to the user after many months only to hear that everything was wrong. This meant the developer had to go back to the drawing board and spend many additional hours before the user could once again review the application.

The process is quite different now. As soon as you have outlined the tasks and the data analysis is complete, the developer can design the tables and establish relationships among them. The form and report prototype process can then begin. Rather than the developer going off for weeks or months before having further interaction with the user, the developer needs only a few days, using the Access wizards, to quickly develop form prototypes.

Testing

As far as testing goes, you just can’t do enough. I recommend that, if your application is going to be run in Windows 2000, Windows 2003, Windows XP, and Windows Vista, you test in all environments. I also suggest you test your application extensively on the lowest common denominator piece of hardware; the application might run great on your machine but show unacceptable performance on your users’ machines.

Testing your application both in pieces and as an integrated application usually helps. Recruit several people to test your application and make sure they range from the most savvy of users to the least computer-adept person you can find. These different types of users will probably find completely different sets of problems. Most importantly, make sure you’re not the only tester of your application, because you’re the least likely person to find errors in your own programs.

Implementation

Your application is finally ready to go out into the world, or at least you hope so! Distribute your application to a subset of your users and make sure they know they’re performing the test case. Make them feel honored to participate as the first users of the system, but warn them that problems might occur, and it’s their responsibility to make you aware of them. If you distribute your application on a wide-scale basis and it doesn’t operate exactly as it should, regaining the confidence of your users will be difficult. That’s why it is so important to roll out your application slowly.

Maintenance

Because Access is such a rapid application-development environment, the maintenance period tends to be much more extended than the one for a mainframe or DOS-based application. Users are much more demanding; the more you give them, the more they want. For a consultant, this is great. Just don’t get into a fixed-bid situation. Because of the scope of the application changing, you could very well end up on the losing end of that deal.

There are three categories of maintenance activities: bug fixes, specification changes, and frills. You need to handle bug fixes as quickly as possible. The implications of specification changes need to be clearly explained to the user, including the time and cost involved in making the requested changes. As far as frills go, try to involve the users as much as possible in adding frills by teaching them how to enhance forms and reports and by making the application as flexible and user-defined as possible. Of course, the final objective of any application is a happy group of productive users.

What’s New in Access 2007?

Access 2007 sports a plethora of new features, all worth taking a look at. Although Microsoft targeted many of the new features to the end user, there are many other useful enhancements in the product. The following sections provide an overview of the new features. I cover each feature in more detail in the appropriate chapter of this book.

What’s New in the User Interface?

The user interface in Microsoft Office Access 2007 has been redesigned from the ground up. Microsoft made this design change to help you find the commands that you need, when you need them. Many features that previously were buried deep within Access’s menu structure are now easily accessible. From the moment you launch Microsoft Office Access 2007 to the time you exit the application, your user experience will be very different from that of Access 2003, or any of the previous versions of Microsoft Access.

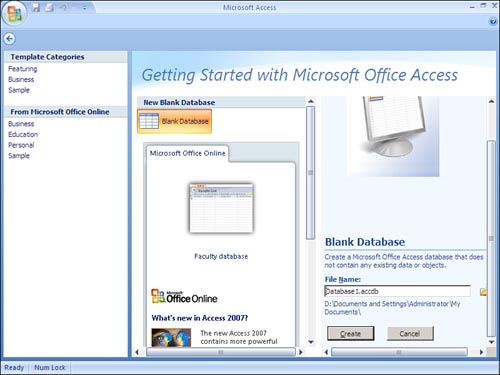

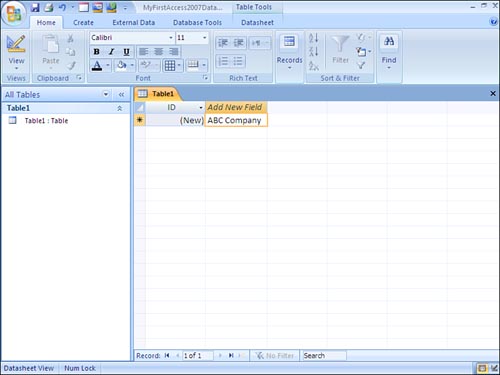

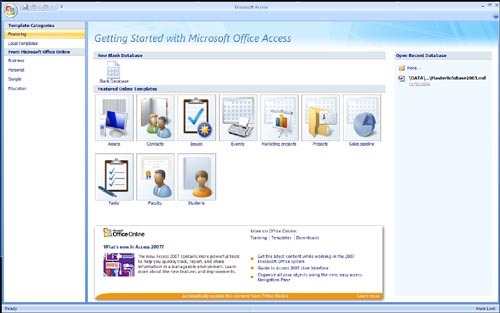

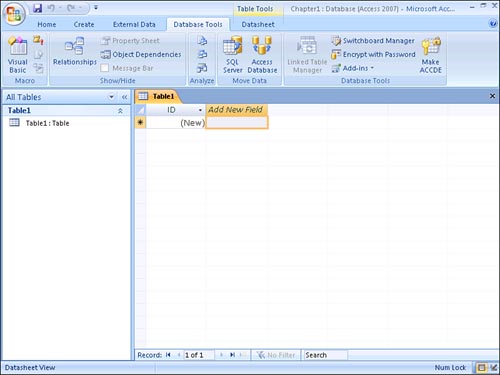

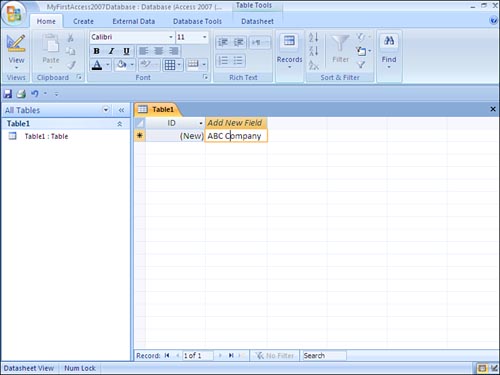

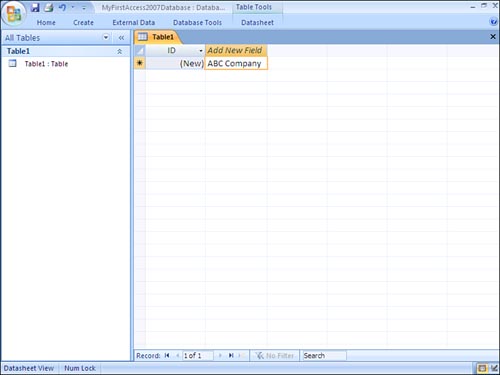

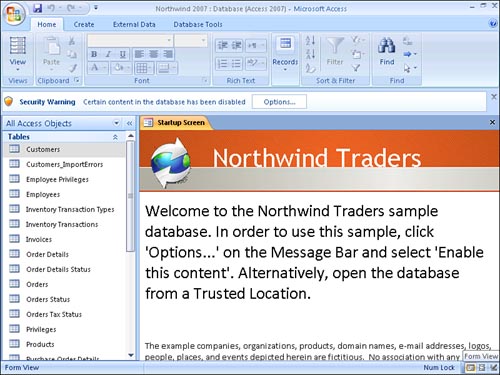

When you launch Access 2007, the screen appears as shown in Figure 1.17. Here, you can opt to create a new blank database, open a recently used database, open other existing databases, or create a new database from a template. If you select Blank Database, Access prompts you for the name and location of the database, as shown in Figure 1.18. When you click Create, the screen appears as shown in Figure 1.19.

Figure 1.17. The Access 2007 desktop looks quite different from that of its predecessors.

Figure 1.18. You must select a name and a location for the database.

Figure 1.19. Access 2007 includes a new tabbed interface.

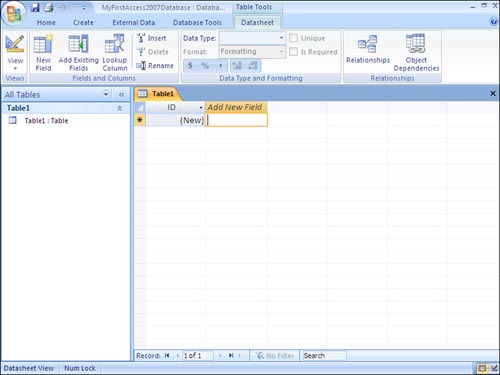

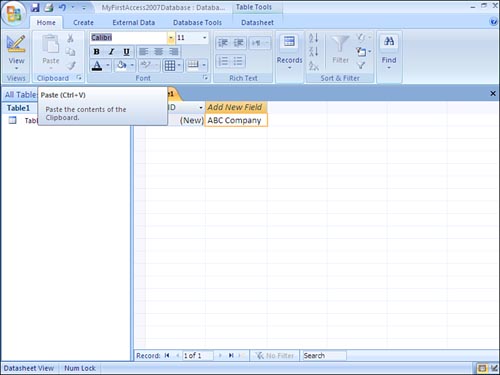

Notice that Microsoft Office Access 2007 provides you with a tabbed interface (see Figure 1.19). When you create a new blank database, Access 2007 provides you with a new datasheet so that you can create the first table contained in the database. You can use this technique to create a table, or you can create a table in Design view. Notice that underneath the tabs is what looks like a fancy toolbar. Microsoft refers to this toolbar as the ribbon. The next section (“Getting to Know the Ribbon”) goes into the details of the ribbon. In the sections that follow, we’ll look at each tab available in Microsoft Office Access 2007.

Getting to Know the Ribbon

The ribbon is the area at the top of the program window; it replaces menus and toolbars. Using the ribbon, you can choose the category of commands with which you want to work. The ribbon contains command tabs and contextual command tabs. The following sections cover both types of tabs.

Exploring the Command Tabs

When you launch Microsoft Office Access 2007, you are presented with a tabbed interface. The tabs displayed include Home, Create, External Data, Database Tools, and Datasheet. This section explores the details of each tab.

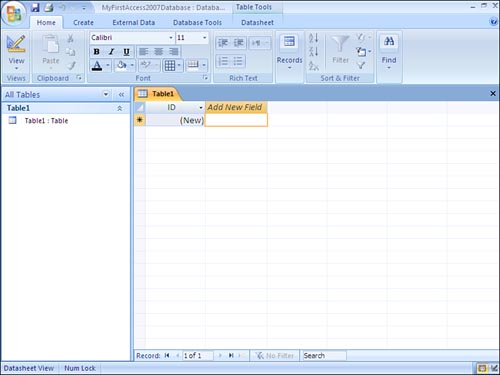

The first tab is the Home tab (see Figure 1.20). It enables you to perform the following types of functions:

- Switch between views (datasheet and design)

- Cut, copy, and paste

- Format text (add bold or underline, change the font, and so on)

- Work with rich text (bulleted lists and numbered lists)

- Work with records (save, total, spell check, and so on)

- Sort and filter data

- Locate data meeting specific criteria

Figure 1.20. The Home tab enables you to perform basic formatting and record-oriented tasks.

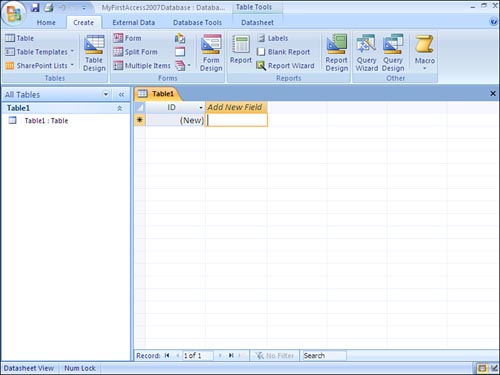

The second tab is the Create tab (see Figure 1.21). It enables you to perform the following types of functions:

- Create tables, table templates, and SharePoint lists

- Create various types of forms

- Create various types of reports

- Create queries and macros

Figure 1.21. The Create tab enables you to create database objects.

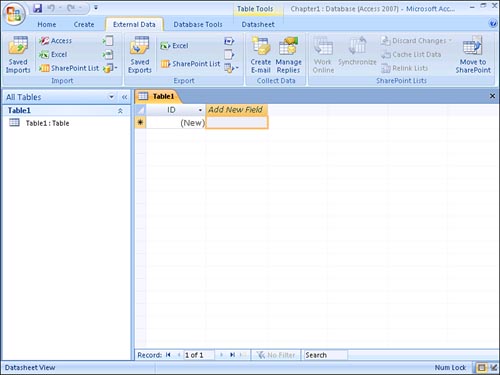

The third tab is the External Data tab (see Figure 1.22). This tab enables you to perform the following types of tasks:

- Process saved imports and exports

- Interface with other Access databases, as well as with Excel spreadsheets, SharePoint lists, text files, XML files, and other databases such as Open Database Connectivity (ODBC) databases

- Create and manage email

Figure 1.22. The External Data tab enables you to interface between Microsoft Office Access 2007 and other applications, such as Excel and SharePoint.

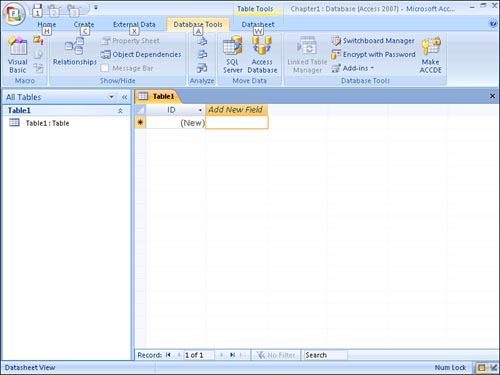

The fourth tab is called the Database Tools tab (see Figure 1.23). It enables you to do the following:

- Launch the Visual Basic editor

- Work with macros

- Work with relationships and object dependencies

- Perform analysis tasks

- Interface with SQL Server

- Work with linked tables

- Manage switchboards

- Encrypt databases

- Work with add-ins

- Compile your database

Figure 1.23. The Database Tools tab enables you to perform miscellaneous database-related tasks.

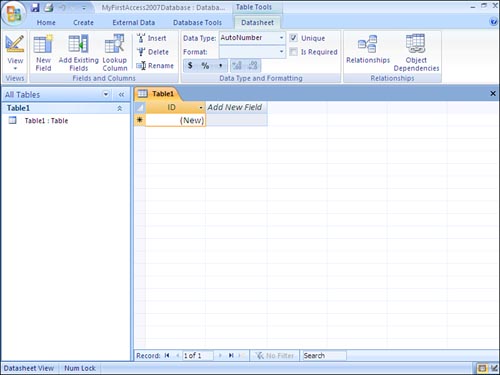

Exploring the Contextual Command Tabs

Other tabs are contextual and therefore vary depending on what you are doing. For example, when you first create a new database, Access assumes that your first task will be to create a new table. It places you in Datasheet view, and the Datasheet tab appears (see Figure 1.24). This tab enables you to perform all tasks relating to the process of working with a datasheet. These tasks include working with fields and columns, modifying the data type and formatting associated with a column, and working with relationships. I cover each context-sensitive tab as appropriate within this shortcut.

Figure 1.24. The Datasheet tab is a contextual tab, available while you are working in Datasheet view.

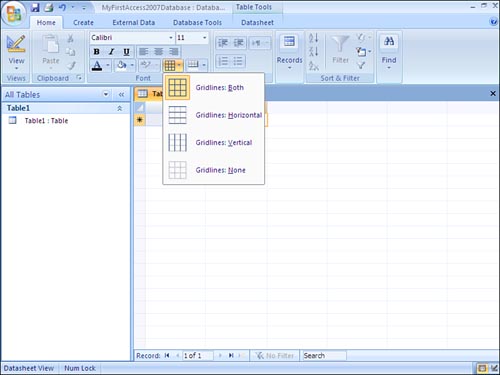

Utilizing the Gallery

The gallery is a control that displays a choice visually so that you can see the results you will get. The idea is to allow you to browse and see what Microsoft Office Access 2007 can do. Figure 1.25 provides an example. As you can see, when you click the arrow on the right side of the Gridlines button, a gallery appears showing you how each result will appear. This feature makes it easy for you to confidently make your selection from the options available.

Figure 1.25. The gallery gives you a preview of the effect that the selected choice will make.

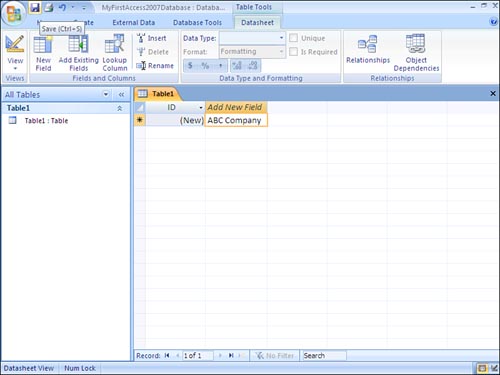

Working with the Quick Access Toolbar

The Quick Access toolbar is a single standard toolbar that appears at the top of the ribbon and provides single-click access to commands such as Save and Undo. Notice the Save, Print, and Undo buttons in Figure 1.26. These buttons are all on the Quick Access toolbar; you can easily access them at any time. You can customize the Quick Access toolbar to include the commands that you use most often. You also can modify the placement and size of the toolbar. As you can see, the small toolbar appears above the command tabs. To change the placement of the Quick Access toolbar, simply right-click the toolbar and select Show Quick Access Toolbar Below the Ribbon. The toolbar appears below the ribbon (see Figure 1.27).

Figure 1.26. The Quick Access toolbar enables you to easily access commonly used commands.

Figure 1.27. You can place the Quick Access toolbar under the ribbon.

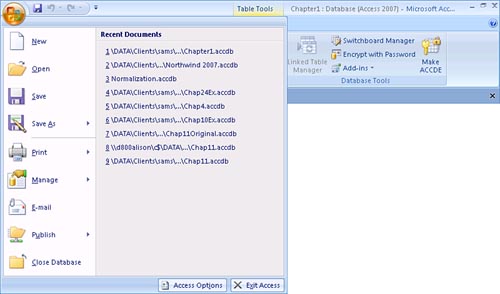

Working with the Microsoft Office Access Button

The Microsoft Office Access button appears in the upper-left corner of the application window. When you click the Microsoft Office Access button, a menu appears (see Figure 1.28). Using the menu, you can perform the following tasks:

- Create new databases

- Open existing databases

- Save changes to the current object

- Use the Save As menu to save to other Access file formats as well as to a web server or to a PDF or XPS file

- Print or print preview

- Manage databases by compacting and repairing them, backing them up, and working with Database properties

- Email your databases to other people

- Close the current database

Figure 1.28. The Microsoft Office Access button provides a menu necessary to perform commonly used commands.

Ribbon Tips and Tricks

You can use the same keyboard shortcuts with Microsoft Office Access 2007 that you could with previous versions of Access. This means that you can perform many of the commonly used features (such as Save) using the keyboard shortcuts that you are familiar with. When you hover your mouse pointer over the ribbon on a button that is associated with a keyboard shortcut, the shortcut appears as a ToolTip (see Figure 1.29).

Figure 1.29. When you hover your mouse pointer over a command associated with a keyboard shortcut, the shortcut appears as a ToolTip.

Another way in which you can identify keyboard shortcuts is to press your Alt key while on a particular tab. All the Alt key shortcuts appear as small indicators (see Figure 1.30). For example, when you press Alt with the Home tab active, you can see that Alt+F will access the Microsoft Office Access button.

Figure 1.30. If you press the Alt key on your keyboard, the Alt shortcuts appear as small indicators.

Sometimes you are going to want extra screen real estate and will want to collapse the ribbon so that only the active command tab appears. Microsoft Office Access 2007 makes this quite easy. To collapse the ribbon, double-click the active command tab. Your application window appears as in Figure 1.31. To open it again, simply click the tab you want to activate.

Figure 1.31. Double-click the ribbon to collapse it.

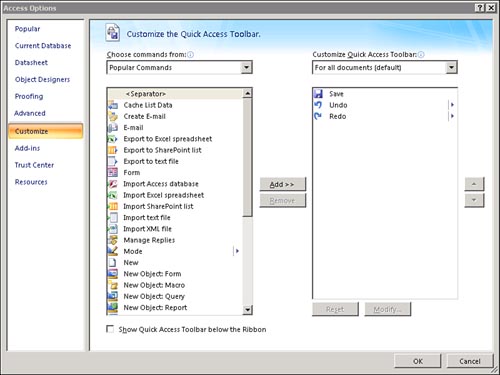

Customizing the Quick Access Toolbar

As mentioned in the section “Working with the Quick Access Toolbar,” you can customize the Quick Access toolbar. To do so, right-click the toolbar; a context-sensitive menu appears (see Figure 1.32). Select Customize Quick Access Toolbar. The Access Options dialog box appears with the Customization page selected (see Figure 1.33). The following steps show you how to customize the Quick Access toolbar:

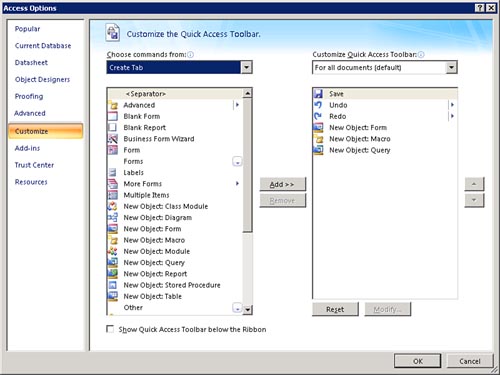

- Use the Choose Commands From drop-down list to select the category of commands from which you want to choose. For example, in Figure 1.34, the Create commands are selected.

Figure 1.32. When you right-click the Quick Access toolbar, a context-sensitive menu appears.

Figure 1.33. The Customization page of the Access Options dialog box enables you to customize the Quick Access toolbar.

Figure 1.34. After you select Add, the command appears in the list box on the right side of the dialog box.

- Use the Customize Quick Access Toolbar drop-down list to determine whether your changes will apply for all documents (databases) or for only the specific document that you are working with.

- Select a command from the list box on the left side of the dialog box and click Add to add it to the list box on the right side of the dialog box. For example, in Figure 1.34, the Blank Form command has been added from the Create Tab options.

- Use the up and down arrows on the right side of the dialog box to move the command up or down within the list of existing commands.

- After you add all the desired commands, click OK to complete the process. The Quick Access toolbar now appears with the icons associated with the commands that you added to the toolbar (see Figure 1.35).

Figure 1.35. After you add three commands to the Quick Access toolbar, they appear next to the existing toolbar buttons.

Tip

If you want to reset the Quick Access toolbar to its default state, click the Reset button on the Customization page of the Access Options dialog box.

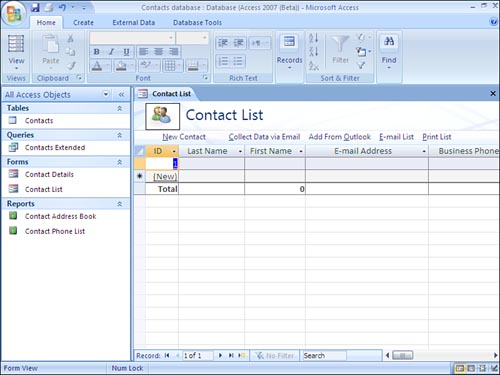

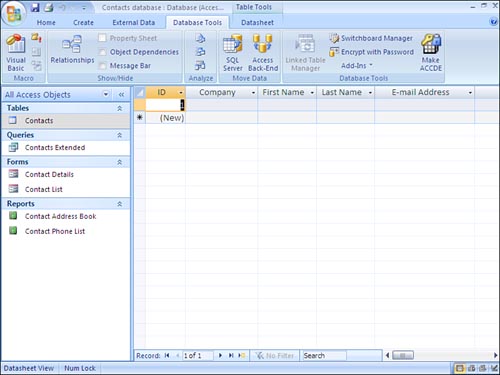

Getting to Know the Navigation Pane

Microsoft has replaced the Database window with the Navigation Pane. The Navigation Pane contains the names of all the objects in your database, including the forms, reports, pages, macros, and modules that compose your database. In Figure 1.36, you can see that the Contacts database is composed of one table, one query, two forms, and two reports.

Figure 1.36. The Navigation Pane enables you to select and work with the appropriate database object.

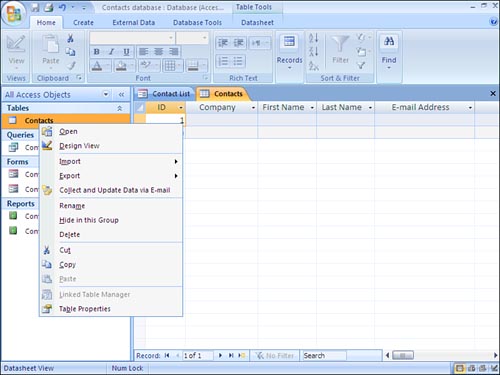

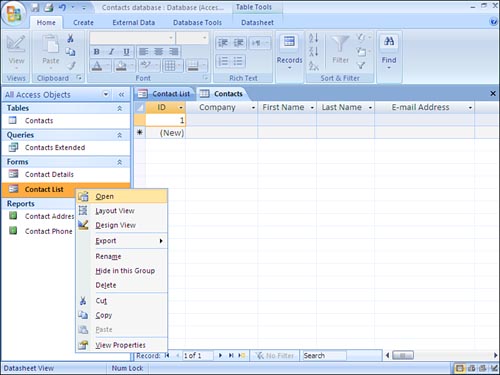

Applying a command to a database object is easy; simply right-click the object, and a context-sensitive menu appears. For example, the context-sensitive menu associated with the Contacts table enables you to open, design, import, export, delete, and perform other important functionality necessary when administering a table (see Figure 1.37). Another example is the context-sensitive menu that appears when you right-click a form. Notice in Figure 1.38 that the options for a form are quite different from those for a table. They include the ability to work with the form in various views; to export, rename, and delete the form; as well as to view form properties.

Figure 1.37. After you right-click a table, the context-sensitive menu enables you to perform functionality associated with a table.

Figure 1.38. After you right-click a form, the context-sensitive menu enables you to perform functionality associated with a form.

Working with Tabbed Documents

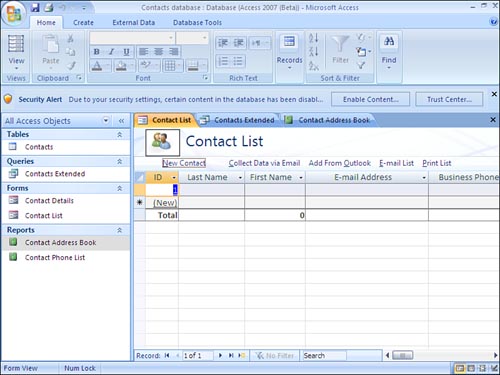

In Microsoft Office Access 2003, all open documents (forms, reports, and so on) appeared on the taskbar. Microsoft has replaced this paradigm with that of tabbed documents. When you have open forms, reports, and other objects, they appear as tabs on the ribbon (see Figure 1.39). You can easily move from object to object by simply clicking each tab. Notice in Figure 1.39 that three objects are open: Contact List, Contacts Extended, and Contact Address Book. The Contact List form is currently the active tab.

Figure 1.39. Each open document appears as a tab on the ribbon.

Showing or Hiding Document Tabs

If you prefer the older style of either viewing only one object at a time or of overlapping windows that appear on the taskbar, you can change the behavior of Access by using Access Options. Follow these steps to view only one object at a time:

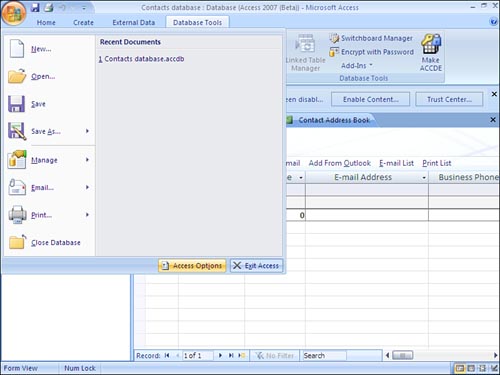

- Click the Microsoft Office button.

- Select Access Options (see Figure 1.40). The Access Options dialog box appears.

Figure 1.40. Access Options enables you to modify the behavior of Access and specific databases.

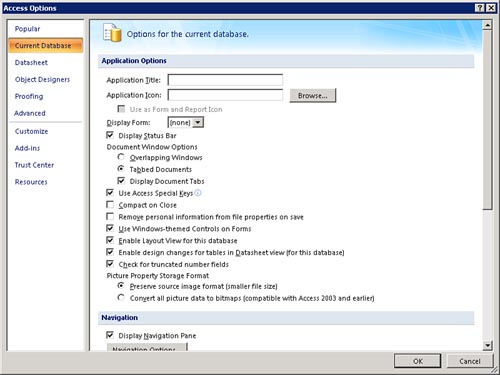

- Click Current Database. Your screen should appear as in Figure 1.41.

Figure 1.41. The Current Database options affect the behavior of a specific database.

- In the Application Options section, click Display Document Tabs to deselect it.

- Click OK to close the dialog box. You will receive a message indicating that you must close and reopen the current database for the specified option to take effect.

- Close and reopen the database to see the changes take effect. Your screen should now appear as in Figure 1.42. Notice that no tabs appear under the ribbon.

Figure 1.42. After you close and reopen the database, no tabs appear under the ribbon.

Displaying Overlapping Windows

Another option is to display overlapping windows. Here are the steps involved:

- Click the Microsoft Office button.

- Select Access Options. The Access Options dialog box appears.

- Click Current Database.

- Click Overlapping Windows to select it.

- Click OK to close the dialog box.

- Close and reopen the database to see the changes take effect. Your screen should now appear as in Figure 1.43. Notice that no tabs appear under the ribbon.

Figure 1.43. After you close and reopen the database, you can see each object as an overlapping window.

Note

The Display Documents Tabs setting is a per-database setting. You must modify this setting for each database. New databases created using Access 2007 show document tabs by default. Databases created in earlier versions of Access use overlapping windows by default.

Exploring the New Status Bar

The status bar in Microsoft Office Access 2007 is similar to that of earlier versions of Access but sports some new features. In addition to showing status messages, property hints, progress indicators, and other features familiar to earlier versions of Access, the new status bar enables you to modify the current view and to zoom. It also provides rich right-click functionality.

You can quickly and easily modify the view you are working with by simply clicking the appropriate tool in the lower-right corner of the status bar (see Figure 1.44). For example, when a form is open, you can switch among Form view, Datasheet view, Layout view, and Design view. When a table is open, you can switch among Datasheet view, PivotTable view, PivotChart view, and Design view.

Figure 1.44. You can modify the view that you are working with by clicking the appropriate tool on the status bar.

Another feature of the new status bar is the capability to adjust the zoom level to zoom in or out. You do this by using the slider on the status bar.

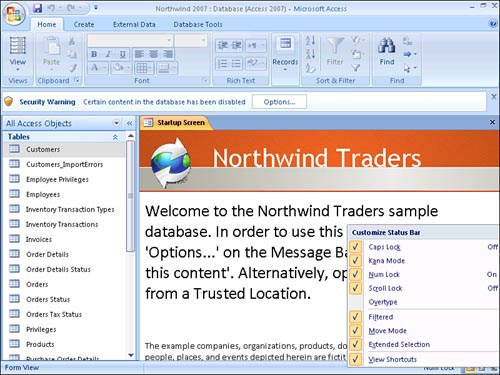

Finally, the new status bar provides a host of commands that are available when you right-click it. Notice in Figure 1.45 that you can perform commands such as changing the Caps Lock setting, the Num Lock setting, and whether the data is filtered. You simply click to select or deselect the appropriate setting.

Figure 1.45. When you right-click on the status bar, you can perform many commands.

Showing or Hiding the Status Bar

Microsoft Office Access 2007 gives you the option of hiding or showing the status bar. The following are the steps you must take to change the visibility of the status bar:

- Click the Microsoft Office button.

- Select Access Options. The Access Options dialog box appears.

- Click Current Database.

- Click within the Application Options section to deselect Display Status Bar.

- Click OK to close the dialog box.

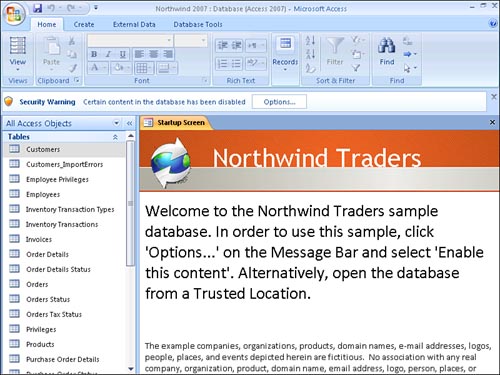

- Close and reopen the database. The status bar should no longer be visible (see Figure 1.46).

Figure 1.46. After you close and reopen the database, the status bar no longer appears.

Working with the Mini Toolbar

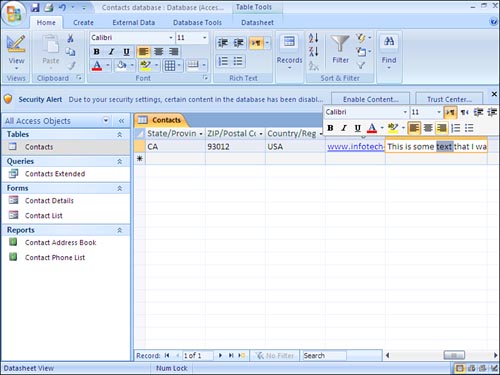

Microsoft Office Access 2007 offers many text formatting features. In earlier versions of Access, formatting text required using a menu or displaying the formatting toolbar. The mini toolbar enables you to easily access formatting features without having to use menus or display a toolbar. Here’s how:

- Select the text you want to change. (The text must be in a memo field using the rich text feature.) The mini toolbar appears above the selected text (see Figure 1.47).

Figure 1.47. After you select text, the mini toolbar appears above the selected text.

- Click to select the appropriate formatting options (for example, bold).

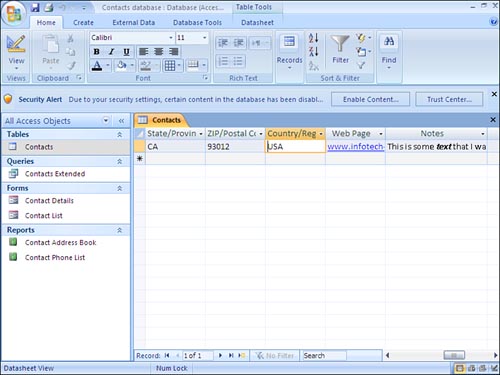

- Move your mouse pointer away from the mini toolbar. The mini toolbar fades away, and the text appears with the selected formatting (see Figure 1.48).

Figure 1.48. Notice that the word text in the Notes field is bold and italic.

Note

If you don’t want to apply formatting to a selection, simply move your mouse pointer a few pixels away from the toolbar, and the mini toolbar disappears.

Note

You can apply formatting only in specific situations, such as within a Memo field where the Text Format property is set to Rich Text.

What’s New with Forms?

The number of new features available with forms in Access 2007 is so vast that I will provide an overview here and then will supply the details in Chapter 5. The features new to forms include the following:

- The ability to quickly create a form with Quick Create

- A new view called Layout view

- The ability to work with Stacked and Tabular layouts

- Split forms

- Alternating background colors

- New filtering features for form data

What’s New with Reports?

Reports also sport a plethora of new features. Many of the features are similar to those provided for reports. They include the following:

- The ability to create a report with Quick Create

- A new view called Layout view

- The ability to work with Stacked and Tabular layouts

- New Group, Sort, and Totals features

The Exciting World of Pivot Tables and Pivot Charts

Access 2002, 2003, and 2007 enable the user to view any table, query, or form in PivotTable or PivotChart view. Pivot tables and pivot charts enable users to easily perform rather complex data analyses. This means that you can perform many of the data analysis tasks once left to Microsoft Excel directly within Microsoft Access. Pivot tables and pivot charts are available in subforms as well, and you can programmatically react to the events that they raise.

Other New Features Found in Access 2007

Microsoft Office Access 2007 includes greatly improved importing and exporting features. For example, you can now export to PDF and XPS fields. You can also save your importing and exporting specifications so that you can reuse them later. I cover these features in Chapter 20, “Using External Data.”

Microsoft Office Access 2007 is tightly integrated with Microsoft Office Outlook 2007. You can both collect and update data using Microsoft Office Outlook 2007. When you use the new Data Collection feature, Microsoft Office Access 2007 can automatically create a Microsoft Office InfoPath 2007 or HTML form. It can then embed that form in an email message. You can then send it to selected Outlook contacts or even to contacts stored in an Access database. When the recipient fills out the form and returns it, you can seamlessly store the resulting data in your Microsoft Office Access 2007 database.

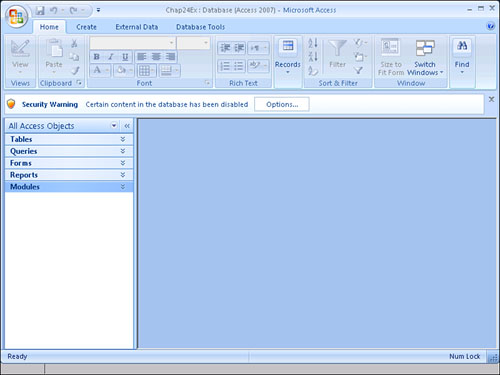

In addition, Microsoft has completely revamped security in Microsoft Office Access 2007. The User Security model has been completely eliminated in Access 2007, unless you keep your database in the old Access file format (.mdb or .mde) and that database already has user-level security applied. In other words, if you open a database created in an earlier version of Access and that database already has security applied, Access 2007 will support user-level security for that database. If you convert a database created in an earlier version of Access to the Access 2007 file format, Access 2007 will strip all user-level security settings from the database, and Access 2007 security will apply. You will learn much more about security in Chapter 31, “Database Security Made Easy.”

What Happened to Replication?

Replication is not supported in Microsoft Office Access 2007, unless you keep your database in the old Access file format. If you open an existing .mdb file where replication has already been implemented, the replication will be supported. You can also use Access 2007 to replicate a database created in an earlier version of Access, as long as you do not convert that database to the new file format.

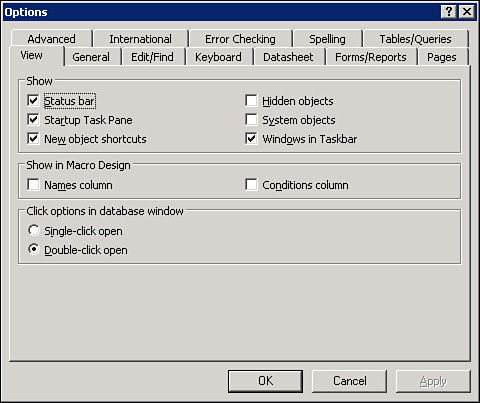

You will not be able to convert a replicated database to the Access 2007 file format. However, there is a solution, which involves manually re-creating the database in the Access 2007 file format. You should do this only if you feel that the benefits afforded by the Access 2007 file format outweigh the benefit received from replication. If you do decide to manually re-create the database, you must first make sure that all hidden and system objects are available. Then do the following:

- Open the replica that you want to convert using the same version of Access in which you created it.

- Select Tools, Options.

- Click the View tab. The Options dialog box appears, as in Figure 1.49.

Figure 1.49. The Options dialog box allows you to view hidden and system objects.

- In the Show section, select Hidden Objects and System Objects.

- Click OK to apply your settings and close the Options dialog box.

Re-Creating the Database

Next, you must manually re-create the database. Here’s how:

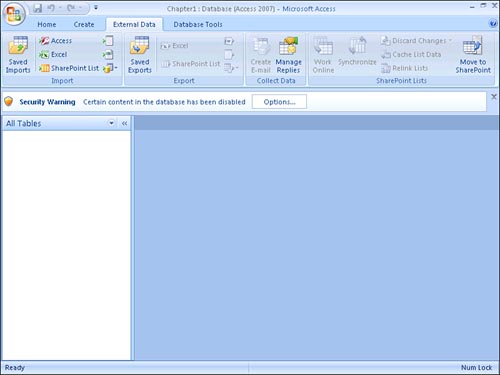

- Create a blank Access 2007 database and open it.

- Close the table called Table1 without saving it.

- Click the External Data tab (see Figure 1.50).

Figure 1.50. You use the External Data tab to import and export data.

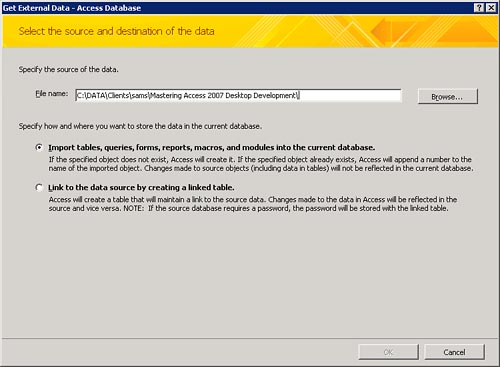

- In the Import group, select Access. The Get External Data – Access Database dialog box appears (see Figure 1.51).

Figure 1.51. The Get External Data – Access Database dialog box prompts you to locate the database whose objects you are importing.

- Browse to locate the replicated database, and then click Open.

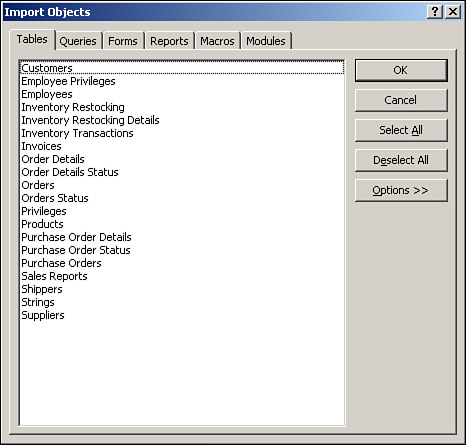

- In the Get External Data – Access Database dialog box, click Import Tables, Queries, Forms, Reports, Macros, and Modules into the Current Database and then click OK. The Import Objects dialog box appears (see Figure 1.52).

Figure 1.52. The Import Objects dialog box prompts you to select the objects you want to import.

- Click to select the objects that you want to import into the new database. If you want to import all objects, click Select All on each tab. Do not select any tables. You will handle them separately.

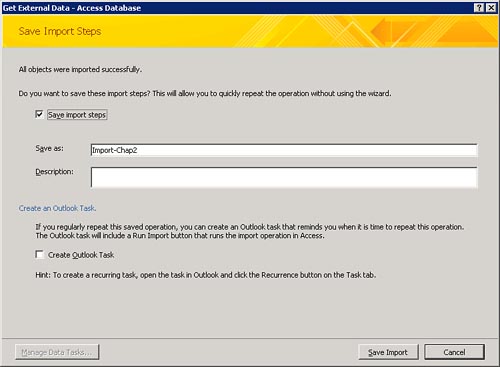

- Access prompts you to save your import steps. If you want to do so, click the Save Import Steps check box, enter the required information (see Figure 1.53), and then click Save Import.

Figure 1.53. Select Save Import if you plan to perform the import process again at a later time.

- Open the replicated database in Access 2007.

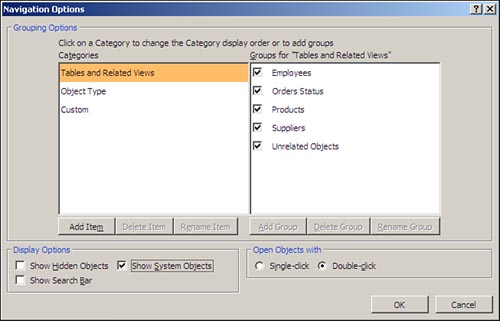

- Make sure that the s_GUID, s_Lineage, and s_Generation fields are visible. To do this, right-click the top of the Navigation Pane and select Navigation Options. The Navigation Options dialog box appears (see Figure 1.54).

Figure 1.54. Use the Navigation Options dialog box to indicate that you want to display system objects.

- Select Show System Objects in the Display Options section. Click OK to close the dialog box.

- Create a Make Table query for each table in the database. The Make Table query will take all the data in the old table and create a table in the new database with the same data. If the s_GUID is a primary key that acts as a foreign key in other tables, you must include the s_GUID field in the new table. There is no need to copy the s_Lineage and s_Generation fields to the new table.

- Run the Make Table queries. This will create the tables in the new database. It’s important to note that the new table will not inherit any of the field properties, and it will not inherit the primary key setting from the original table.

- In the new database, create the same index and primary key used in the replica’s tables.

- Create the necessary relationships for each table in the new database.

- Save your new database.

What Happened to ADP Files?

Access Data Project (ADP) is also no longer supported in Microsoft Office Access 2007, again unless you keep your database in the old Access file format. Although supported with the old Access file format, it is probably best that you do not do any new development with ADP files. If you have existing ADP files that are currently meeting your business needs, you don’t need to rewrite them at this time. If you decide at some point to make major changes to those existing applications, that is when you should consider moving them to the new .accdb or .accde file format and rewriting their functionality as necessary to take advantage of the new features available in Microsoft Office Access 2007 and eliminating the features specific to ADP files.

Additional Tips and Tricks

There are a few additional tips and tricks that you should be aware of when working with Microsoft Office Access 2007. They include advanced Navigation Pane techniques and the process of working with multi-valued fields. The following sections discuss each of these topics in detail.

Advanced Navigation Pane Techniques

Microsoft Office Access 2007 sports some wonderful Navigation Pane techniques that you should be aware of. These include the capability to create custom categories and groups, show or hide the groups or objects in a category, and remove and restore objects in custom groups. Let’s start with the process of creating custom categories. Here are the steps involved:

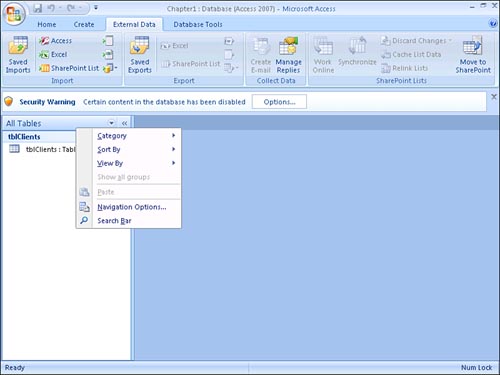

- Right-click the menu at the top of the Navigation Pane. A cascading menu appears (see Figure 1.55).

Figure 1.55. A cascading menu enables you to control the behavior of the Navigation Pane.

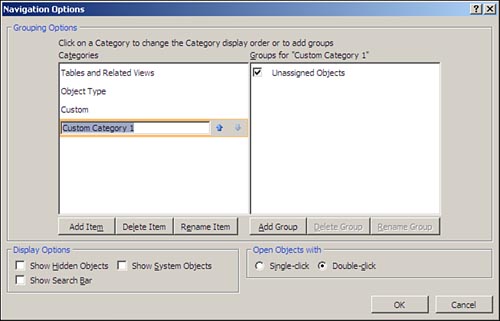

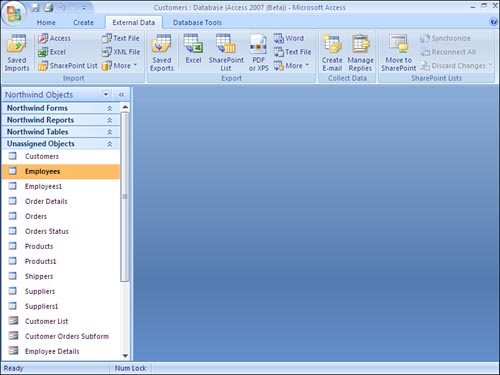

- Select Navigation Options. The Navigation Options dialog box appears (see Figure 1.56).

Figure 1.56. The Navigation Options dialog box enables you to manipulate important features of the Navigation Pane.

- Click Add Item to add a category. Your dialog box appears as in Figure 1.57.

Figure 1.57. You can easily add a category to the Navigation Pane.

- Type the name of the new category.

- Use the up and down arrows to move the category up or down in the list.

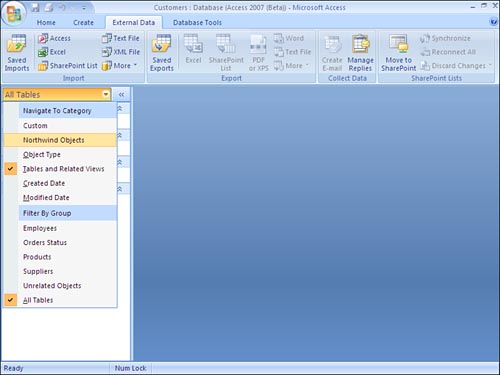

- Click OK to close the dialog box. If you left-click the Navigation Pane menu, you will see your new category in the list (see Figure 1.58).

Figure 1.58. After you create a custom category, you will see it in the list of available categories.

Adding Custom Groups to the Category

After you have created a custom category, you will want to add custom groups to it. Here are the steps involved:

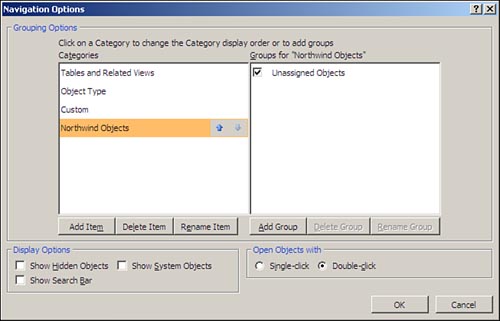

- Right-click the menu at the top of the Navigation Pane and select Navigation Options. The Navigation Options dialog box appears.

- Click to select the category to which you want to add groups. In Figure 1.59, Northwind Objects is selected.

Figure 1.59. Select the category to which you want to add groups.

- Click the Add Group command button. A new group appears.

- Type the name of the new group.

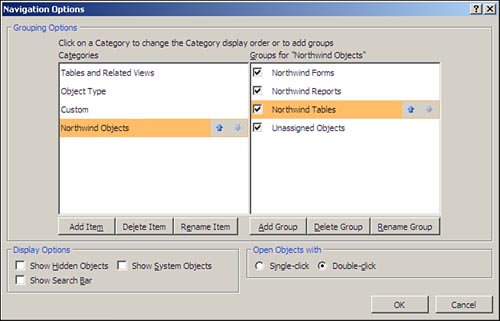

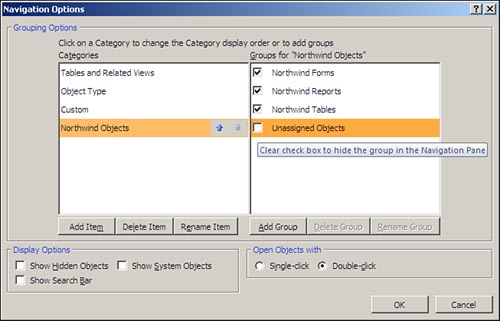

- Continue adding new groups to the category. When you are finished, the Navigation Options dialog box should appear as in Figure 1.60.

Figure 1.60. After you add groups, they appear in the dialog box.

- Click OK to close the dialog box. The groups now appear within the category (see Figure 1.61).

Figure 1.61. After you close the dialog box, the new groups appear within the category.

Note

You can create a maximum of 10 custom categories. Of course, you can rename or delete categories at any time.

Adding Objects to Custom Groups

You are now ready to add objects to your custom groups. Here’s how:

- Click to select the category to which you want to add the new objects.

- In the Unassigned Objects group, select the objects you want to include in your custom group and then move them to the group. You can drag the items individually; hold down the Ctrl key and click and drag multiple items; or right-click one of the selected items, point to Add to Group, and then click the name of the custom group. Regardless of the method, Access adds the objects to the designated group.

Note

When you add a database object from the Unassigned Objects group to a custom group, you are creating a shortcut to the object. If you remove the object from the custom group, you are not removing the object. Instead, you are removing the shortcut contained in the custom group.

Hiding the Unassigned Objects Group

After you have added all your objects to custom groups, you might want to hide the Unassigned Objects group. The process is quite simple:

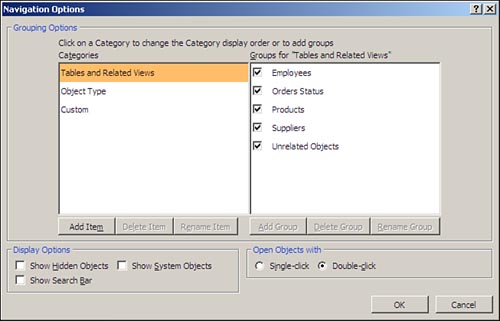

- Right-click the menu at the top of the Navigation Pane and select Navigation Options. The Navigation Options dialog box appears.

- Click to select a category (for example, Northwind Objects).

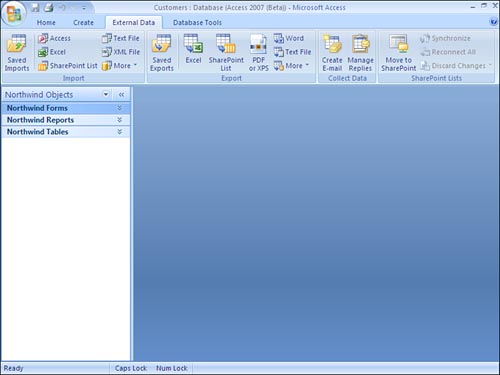

- In the Groups for Category pane (see Figure 1.62), click to clear the Unassigned Objects check box.

Figure 1.62. Click to clear the Unassigned Objects check box.

- Click OK to close the dialog box. The Unassigned Objects group no longer appears (see Figure 1.63).

Figure 1.63. The Unassigned Objects group no longer appears.

Creating a New Custom Group Containing an Object Found in an Existing Group

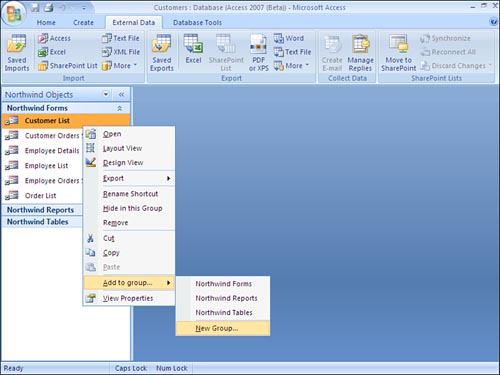

Another trick is to create a new custom group containing an object found in an existing group. To complete this process, you must have a custom category and group containing at least one item. Here’s the process:

- Use the Navigation Pane to view the object you want to place in the new group.

- Right-click the object and select Add to Group, New Group (see Figure 1.64). A new group appears in the Navigation Pane (see Figure 1.65).

Figure 1.64. You can right-click an object and immediately add it to a new group.

Figure 1.65. The new group appears in the Navigation Pane.

- Enter a name for the new group.

- Notice that the object you selected appears in the new group. Drag additional shortcuts to the group as desired.

In addition to what you have learned thus far, you can also show or hide the groups and objects in a category. In fact, you can show or hide some or all of the groups in a custom category and some or all of the objects in a group. There are some important points to remember:

- You can hide an object either via the Navigation Pane or via a property of the object itself.

- You can completely hide objects or groups, or you can simply disable them.

Completing the Process

Now that you know the details of showing or hiding groups and objects in a category, here’s how you finish the process. To hide a group in a category, simply right-click the title bar of the group that you want to hide and then select Hide from the context-sensitive menu. To restore a hidden group to a category, follow these steps:

- Right-click the menu bar at the top of the Navigation Pane and select Navigation Options.

- Click to select the category containing the hidden object.

- In the Groups for Category list, click to select the check box next to the hidden group.

- Click OK. The group should now appear in the Navigation Pane.

Hiding an Object in Its Parent Group

At times you will want to hide an object in its parent group. All you need to do is right-click the specific object that you want to hide and then select Hide. If you want to hide an object from all categories and groups, follow these steps:

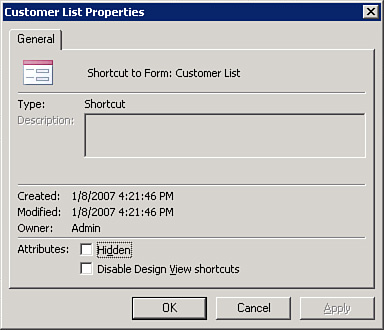

- Right-click the object that you want to hide and select View Properties. The Properties dialog box appears (see Figure 1.66).

Figure 1.66. You use the Properties dialog box to hide an object.

- Click the Hidden check box.

- Click OK. You will no longer see the object in the Navigation Pane.

Restoring a Hidden Object

You are probably wondering how to restore an object after it is hidden. Here’s how:

- Right-click the menu at the top of the Navigation Pane and select Navigation Options from the shortcut menu.

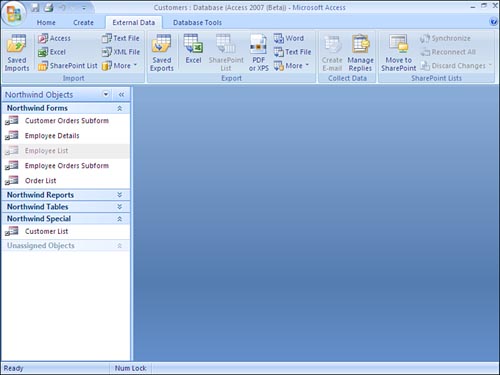

- Under Display Options, click Show Hidden Objects.

- Click OK to close the dialog box and return to the Navigation Pane. The Navigation Pane shows all hidden objects as dimmed (see Figure 1.67).

Figure 1.67. The Navigation Pane shows all hidden objects as dimmed.

- If you hid the object from its parent group and category, right-click the object and select Unhide. If you used the

Hiddenproperty to hide the object from all categories and groups, right-click the object, select View Properties, and then clear the Hidden check box.

You can easily add, remove, or rename an object in a custom group. If you want to delete an item from a custom group, simply right-click the object and select Delete. This action does not remove the object from the database; it simply removes the shortcut from the custom group. The object will appear in the list of Unassigned Objects. You can then add that object to another group. First, you must display the Unassigned Objects group. Then click and drag the object to the appropriate group. Finally, if you want to rename an object, simply right-click it and select Rename Shortcut. Type the new name for the shortcut and press Enter.

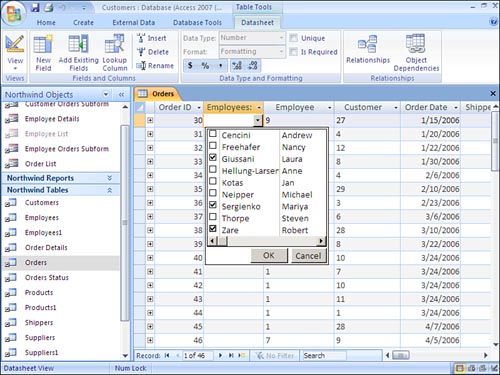

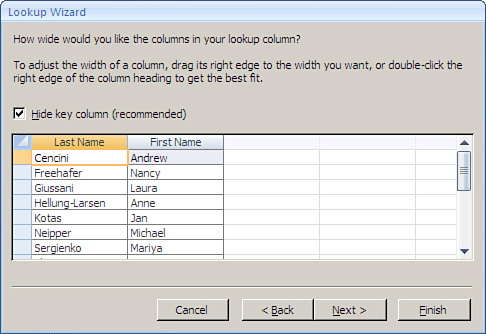

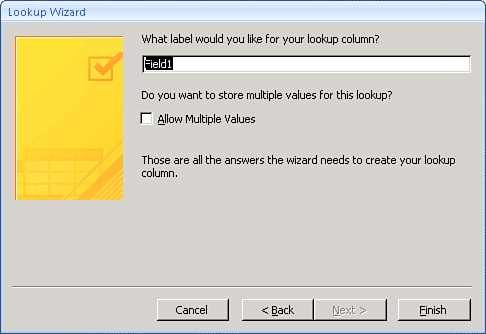

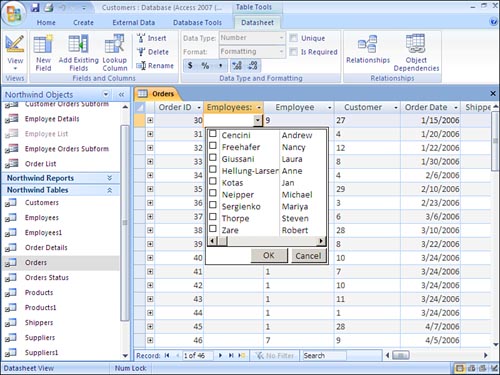

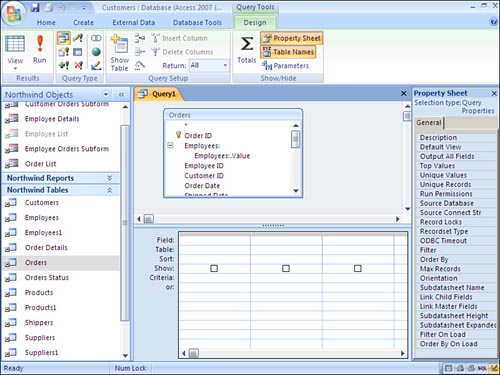

Creating Multi-valued Fields

Another new feature available in Microsoft Office Access 2007 is the new multi-valued field. As its name implies, a multi-valued field is a field that holds multiple values. You can use this to represent a relationship between two tables. For example, an order table can have a multi-valued field for the employee associated with the order, if that order can be associated with multiple employees. When you use the drop-down list in the order to select an employee, the list appears with check boxes. You can select multiple items in the list and then click OK to close the list (see Figure 1.68).

Figure 1.68. You can easily select multiple items in a multi-valued field.

Multi-valued fields are appropriate for specific situations. One of those situations is when you are using Microsoft Office Access 2007 to interface with data stored in Microsoft Windows SharePoint 2007, and that list contains a field that uses one of the multi-valued field types available in Windows SharePoint Services. Another situation is when you want to purposely simplify the database design. Although this seems counter to basic database design principles, it helps to understand that the Microsoft Office 2007 database engine does not actually store the multiple values in a single field. It uses system tables to build the relationship and then visually brings the data back together for the user. If you think about it, you will realize that the relationship between the tables is actually a many-to-many relationship. In this example, an order can be associated with multiple employees, and each employee can be associated with multiple orders.

Multi-valued fields allow Microsoft Office Access 2007 and SharePoint 2007 to be tightly integrated because using multi-valued fields in Access supports the equivalent field type in SharePoint Services. This means that when you link to a SharePoint list containing a multi-valued data type, Access creates a multi-valued data type locally. When you export an Access table to SharePoint, multi-valued fields seamlessly port to SharePoint. In fact, when you move an entire Access database to SharePoint, all the tables containing multi-valued fields become field types available in Windows SharePoint Services.

You might still be wondering when it is appropriate to use multi-valued fields. The following are some guidelines:

- When you want to link to a SharePoint list

- When you plan to export an Access table to a SharePoint site

- When you plan to move an Access database to a SharePoint site

- When you want to store a multi-valued selection from a small list of choices

Caution

Do not use multi-valued fields if you plan to upsize your data to Microsoft SQL Server because SQL Server does not support multi-valued fields. Therefore, when you upsize an Access database to SQL Server, the upsizing process will convert the multi-valued field to an ntext (memo) field containing a delimited list of values.