![]()

If American neoconservatives are liberals mugged by reality, Chinese realists are idealists mugged by the surreal events of the Cultural Revolution. In the case of Yan Xuetong, he grew up in a family of morally upright intellectuals and, at the age of sixteen, was sent to a construction corps in China’s far north, where he stayed for nine years. Here’s how he describes his experience of hardship: “At that time, the Leftist ideology was in full swing. In May, water in Heilongjiang still turns to ice. When we pulled the sowing machine, we were not allowed to wear boots. We walked barefoot over the ice. Our legs were covered in cuts. We carried sacks of seed that could weigh up to eighty kilograms [about 176 pounds]. We carried them along the raised pathways around the paddy fields. These were not level; make a slight misstep and you fell into the water. You just thought of climbing out and going on. When you at last struggled to the end and lay down, your eyes could only see black and you just could not get up. … [W]e saw people being beaten to death, so you became somewhat immune to it.” In 1969, the Voice of America predicted that war could break out on the Sino-Soviet border: “When we young people learned this, we were particularly happy. We hoped that a massive war would improve the country, or at least change our own lives. Today people fear war, but at the time we hoped for immediate action, even to wage a world war. That way we could have hope. In that frame of mind, there was no difference between life and death. There was no point in living.”

Four decades later, Yan Xuetong has emerged as China’s most influential foreign policy analyst and theorist of international relations (in 2008, Foreign Policy named him one of the world’s hundred most influential public intellectuals). He openly recognizes that his experience of hardship in the countryside has shaped his outlook: “[It] gave people the confidence to overcome all obstacles. And this confidence is built precisely on the basis of an estimation of the difficulties faced, on the basis of always preparing for the worst case. Hence, many people who went down to the countryside are realists with regard to life. People who have not experienced hardship are more liable to adopt an optimistic attitude toward international politics.”1

To the outside world, Yan may appear as China’s “Prince of Darkness,” the hawkish policy adviser who is the enemy of liberal internationalists. Mark Leonard, the author of the influential book What Does China Think?, labels Yan as China’s “leading ‘neo-comm,’ an assertive nationalist who has called for a more forthright approach to Taiwan, Japan, and the United States.” A “neo-comm” is China’s equivalent of the American neocon: “The ‘neo-comm’ label will stick because there are so many parallels between Yan Xuetong and his analogues [the neocons] in the USA. Yan Xuetong is almost the mirror image of William Kristol. … Where Kristol is obsessed with a China threat and convinced that US supremacy is the only solution to a peaceful world order, Yan Xuetong is fixated with the USA and sure that China’s military’s modernization is the key to world stability.”2

But Leonard’s account—based on English-language sources—misrepresents Yan’s views. Yan is neither a communist (or Marxist) who believes that economic might is the key to national power nor a neocon who believes that China should rely on military might rather than multilateral organizations to get its way. Yan’s argument is that political leadership is the key to national power and that morality is an essential part of political leadership. Economic and military might matter as components of national power, but they are secondary to political leaders who act (at least partly) in accordance with moral norms. If China’s leaders absorb and act on that insight, they can play a greater role in shaping a peaceful and harmonious world order. Yan is still a political realist, because he believes political leadership shapes international relations; it’s the way the political world actually works, not just an ideal. Moreover, Yan believes that the global order is bound to be hierarchical, with some states being dominant and others less influential. But dominance is achieved mainly by morally informed political leadership rather than economic or military power.

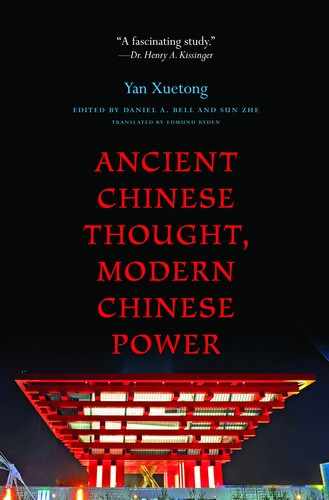

Yan’s theory was shaped by his groundbreaking academic research on ancient Chinese thinkers who wrote about governance and interstate relations during a period of incessant warfare between fragmented states, before China was unified by the first emperor of Qin in 221 BCE. In this way, too, Yan is different from the neocons: he is a scholar as well a political commentator. This book is a translation of Yan’s work on the international political philosophy of ancient Chinese thinkers. The three essays by Yan are followed by critical commentaries by three Chinese scholars. In the last chapter, Yan replies to his critics and draws implications of pre-Qin philosophy for China’s rise today. The book includes three appendixes: a short account of the historical context and the key thinkers of the pre-Qin period that may be helpful for nonexperts, a revealing interview with Yan Xuetong himself, and Yan Xuetong’s discussion of why there is no Chinese school of international relations theory. Readers of this book may not agree with all of Yan’s arguments, but the “neo-comm” label, we hope, will not stick.

THE INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY OF PRE-QIN THINKERS

The Spring and Autumn Period (ca. 770–476 BCE) and the Warring States Period (ca. 475–221 BCE) were a time of ruthless competition for territorial advantage among small states. The various princely states still gave feudal homage to the Zhou king as their common lord but, as Yang Qianru notes in chapter 4, it “was rather like the relationship of the members of today’s Commonwealth to Great Britain. They accept the Queen as the head of the Commonwealth but enjoy equal and independent status along with Great Britain.” The historical reality is that “several large princely states already had two basic features of the modern ‘state’: sovereignty and territory. Not only did the states have independent and autonomous sovereignty, they also had very clear borders.” Arguably, the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods have more in common with the current global system than with imperial China, then held to be the empire (Middle Kingdom) at the center of the world. Hence, it should not be surprising that there emerged a rich discourse of statecraft that may still be relevant for the present-day context. As Yang puts it,

on the grounds of protecting their own security, [the pre-Qin states] sought to develop and resolve the relationships among themselves and the central royal house and thus they accumulated a rich and prolific experience in politics and diplomacy. This complicated and complex political configuration created the space for scholarship to look at the international system, state relations, and interstate political philosophy. The pre-Qin masters wrote books and advanced theories trying to sell to the rulers their ideas on how to run a state and conduct diplomacy and military strategy while they played major roles in advocating strategies of becoming either a humane authority or a hegemon, making either vertical (North-South) or horizontal (East-West) alliances, or either creating alliances or going to war. Scholars who have researched the history of thought have looked only at one side and emphasized the value of the pre-Qin masters’ thought as theory (philosophical, historical, or political), whereas most of these ideas were used to serve practical political and diplomatic purposes among the states. Their effectiveness both then and now is proven. Therefore, there is no doubt about the positive and practical role of researching the foreign relations, state politics, and military strategies of the pre-Qin classics or of applying the insights gleaned from studying these masters to international political thought.3

Chapter 1 is a comprehensive comparison of the theories of interstate politics of seven pre-Qin masters: Guanzi, Laozi, Confucius, Mencius, Mozi, Xunzi, and Hanfeizi. Yan deploys the tools of international relations theory to analyze their ways of thinking and what they say about interstate order, interstate leadership, and transfer of hegemonic power. Yan’s analysis shows that there is a wide diversity of perspectives in pre-Qin international political philosophy. But there are also commonalities: “the pre-Qin thinkers hold that morality and the interstate order are directly related, especially at the level of the personal morality of the leader and its role in determining the stability of interstate order.” Rulers concerned with successful governance in a world of shifting allegiances and power imbalances also need to employ talented advisors: “Confucius, Mencius, Xunzi, Mozi, and Guanzi all explain shifts in hegemonic power through the one mediating variable of the need to employ worthy people, that is, all of them think that employing worthy and capable persons is a necessary, even the crucial, condition for successful governance.” And if the rulers want to strive for the morally highest form of political rule, the pre-Qin thinkers (with the exception of Hanfeizi) all agree that the basis of humane authority is the moral level of the state. Yan does not say so explicitly, but there is a strong presumption that areas of agreement among such diverse thinkers must approximate how international politics works in reality.

In her commentary (chapter 4), Yang Qianru objects to Yan’s social scientific method on the grounds that it abstracts from concrete historical contexts and is driven by the aim of constructing an explanatory model that allows the researcher to draw normative conclusions of universal significance and to analyze China’s rise. Yang does not object to the methods of international political theory per se, but she argues that “we need to correctly grasp the reality of historical texts and the thought of pre-Qin masters, and then deepen and expand the areas and perspectives of current research.” But perhaps Yan and Yang are not so far apart; it’s more a matter of two methodologies with different emphases that can enrich each other. Yan does aim to “grasp the true picture [my emphasis] of pre-Qin thought so as to make new discoveries in theory.” In principle, he could distort the ideas of pre-Qin thinkers for the purpose of creating new theories or drawing implications for China’s rise, but he doesn’t do that: at some level, he is concerned with historical truth. So the more historically minded interpreters can help Yan’s project by correcting and improving his account of pre-Qin thinkers; if they think his account is wrong, let them draw on detailed accounts of the historical context to explain the problem. As for the historically minded interpreters, they can learn from Yan’s research so that investigations of the pre-Qin historical context will be guided by questions that are of greater theoretical and political relevance today.

In chapter 2, Yan focuses more specifically on Xunzi’s interstate political philosophy. Xunzi (ca. 313–238 BCE) is the great synthesizer of international political philosophy of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. Although he generally upholds Confucian moral principles, he begins with dark assumptions about human nature and is explicitly concerned with appropriate strategies for nonideal political contexts. In contrast to modern ideas of equality of sovereignty, Xunzi argues for hierarchies among states, with powerful states having extra responsibility to secure international order. Xunzi distinguishes among three kinds of international power, in decreasing order of goodness: humane authority, hegemony, and tyranny. Tyranny, which is based on military force and stratagems, inevitably creates enemies and should be avoided at all costs. In an anarchic world of self-interested states, the hegemonic state may have a degree of morality because it is reliable in its strategies: domestically it does not cheat the people, and externally it does not cheat its allies. But strategic reliability must also have a basis in hard power so that the hegemon gains the trust of its allies. For Xunzi, humane authority, meaning a state that wins the hearts of the people at home and abroad, is the ultimate aim. Humane authority is founded on the superior moral power of the ruler himself. Yan comments:

We would have difficulty finding a political leader who meets Xunzi’s standard, but if one compares F. D. Roosevelt as president of the United States during World War II and the recent George W. Bush, we can see what Xunzi means about the moral power of the leader playing a role in establishing international norms and changing the international system. Roosevelt’s belief in world peace was the impetus for the foundation of the United Nations after World War II, whereas Bush’s Christian fundamentalist beliefs led to the United States continually flouting international norms, which resulted in a decline of the international nonproliferation regime.

Yan agrees that humane authority should be the aim of the state, though he criticizes Xunzi for overlooking the fact that humane authority must also have a basis in hard power: “Lacking strong power or failing to play a full part in international affairs and having only moral authority is not sufficient to enable a state to attain world leadership.”

In his commentary (chapter 5), Xu Jin argues that it is difficult for Xunzi to argue that hierarchical norms can be “implemented or maintained when there are evil persons (or evil states) that seek their own ends by flouting norms, especially when these people (or states) have considerable force.” Xu suggests that it is easier to support Xunzi’s political conclusions with Mencius’s view that human beings have a natural inclination toward the good. Moreover, Mencius can contribute to the debate about how to implement humane authority: in addition to emphasizing the morality of the ruler, he puts forward detailed proposals such as light taxation and a land-distribution system meant to secure the basic requirements for life for the common people.

Yan’s third chapter (cowritten with Huang Yuxing) provides a detailed picture of the hegemonic philosophy of The Stratagems of the Warring States. This book has not been regarded as a major philosophical treatise but it is a valuable historical resource for theorizing about the foundations of hegemonic power, the role of norms in a hegemony, and the basic strategies for attaining hegemony. Yan and Huang compare their findings with contemporary Western hegemonic theory and propose that ancient Chinese thinkers saw political power as the core of hegemony, with government by worthy and competent persons as its guarantee. Even a text that recounts the strategies of annexation and alliance of hard-nosed politicians stresses the importance of respect for interstate norms in attaining or maintaining hegemony: “Without the support of norms and relying only on power, the strategists of the Warring States Period could not have attained hegemony; hence, their emphasis on interstate norms is genuine and not primarily intended as a cloak for a profit motive.” Yan and Huang draw on a recent case to illustrate the point that failing to respect interstate norms will have a negative influence on a state’s hegemonic status: “The unilateralist foreign policy of President George W. Bush weakened the international political mobilizing capacity of the United States.”

In his commentary (chapter 6), Wang Rihua expands on strategies for achieving hegemony by drawing on other texts from the pre-Qin period. He points to the frequency of covenant meetings in the period that performed the political functions of affirming hegemony, controlling allies and preventing them from falling away from the alliance, and determining international norms so that the will of the hegemonic state became the international consensus, thus institutionalizing the hegemony. Moreover, political hegemonic theory of the period, like just-war theory today, preferred the military strategy of acting in response to aggression rather than launching wars of aggression. It also stressed that hegemonic states had the duty of providing security guarantees to small and medium-size states, and economic assistance in times of danger, such as famine. But Wang reminds us that “the ancient Chinese classics, including The Stratagems of the Warring States, all acknowledge that the main distinction in power is between humane authority and hegemony.” Pre-Qin thinkers held that the exercise of hegemonic power over other states within a fragmented world, even if the power is informed by morality, is inferior to the exercise of humane authority in a world where there is a single ruler over everything under heaven.

RETHINKING CONTEMPORARY INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THEORIES

Yan makes use of the analytical tools of modern international relations theory to sharpen understanding of the international political philosophy of pre-Qin thinkers. But the pre-Qin thinkers can also help to improve modern theories. International relations theory has been shaped primarily by the history and conceptual language of Western countries, and Yan aims to enrich it with the discourse of ancient Chinese thought. The pre-Qin era is a rich resource not just in the sense that the historical context approximates the contemporary world of sovereign states in an anarchic world, but also because they were writing for political actors, not their academic colleagues: “What pre-Qin thinkers have to say about international relations is all grounded in policy; their thought is oriented toward practical political policies.” Yan is explicit, however, that the aim should not be to produce a distinctively Chinese school of international relations theory. Rather, scholars should aim to improve international relations theory with the insights of pre-Qin thinkers so that it can better understand and predict our interstate world. So what lessons can be drawn from pre-Qin international political philosophy?

Yan stresses that the pre-Qin thinkers discussed in the book, with the exception of Hanfeizi, were conceptual rather than material determinists: they believed that shifts in international power relations are explained more by ideas than by material wealth and military might. In today’s international relations theory, in contrast, “the two well-developed theories are realism and liberalism, and both of these schools look at international relations from the point of view of material benefit and material force.” Yan believes that such theories would become more realistic and have greater policy relevance and predictive power if they took more seriously the role of concepts and morality in shaping international affairs. Constructivism and international political psychology have recently emerged in response to concerns about the material determinism of international relations theory, but “these two theories are not yet mature … and they are stuck at the academic level.”

Even Hanfeizi, notorious for his extreme cynicism, allows for the possibility that morality matters in certain contexts—when humans face nonhuman threats—and Yan argues that Han’s view may become increasingly relevant in the contemporary world, with implications for theorizing about security in new ways:

It shows that with, today’s rise of nontraditional threats to security and the decline of traditional threats to security, morality may play a greater role in international security cooperation than in the cold war period of security attained between two opposing military blocs. Apart from terrorism, nontraditional security threats are basically nonhuman threats to security, such as the financial crisis, the energy crisis, environmental pollution, and climate change. Climate change especially is seen as an increasingly grave threat to international security. Reducing carbon dioxide emissions has become a moral issue. Research on security theory may have to take a moral angle to analyze conflict, cooperation, success or failure, and position shifts in the area of nontraditional security.

The pre-Qin understanding that the basis of international authority is the moral level of the leading state can also enrich modern theories: “The theory of hegemonic stability in contemporary international relations theory has overlooked the relationship between the nature of hegemonic power and the stability of the international order. … According to [the pre-Qin thinkers’] way of thinking, we can suppose that the level of morality of the hegemon is related to the degree of stability of the international system and the length of time of its endurance.” Yan supports this hypothesis with examples from the imperial history of Western great powers: “Throughout history, Great Britain and France, respectively, adopted policies of indirect and direct administration of their colonies. Great Britain’s colonial policy was gentler than France’s, with the result that violent opposition movements were less frequent in British than in French colonies.”

According to pre-Qin thought, the moral level of a state is determined primarily by the quality of the state’s leaders. Yan spells out the implications for contemporary international relations theory: “The theory of imperial overstretch and the coalition politics theory both explain the fall of hegemonic power in terms of excessive consumption of the hegemon’s material strength and overlook the fact that under different leaders the same state evinces a difference in the rise and fall of its power.” Pre-Qin thinkers had specific views about what aspects of political leadership influence shifts in international power: “for the most part they think that it has to do with whether worthy people are employed.” The competition for talent is a feature of the knowledge economy, suggesting that the pre-Qin thinkers may have hit upon a more universal rule that helps to explain the rise and fall of great powers: “If competitiveness among large states more than two thousand years ago and competitiveness among large states in the contemporary globalized world both involve competition for talent, this implies that competition for talent is not a phenomenon peculiar to the era of the knowledge economy but rather is the essence of competition among great powers.” Yan is clearly persuaded by the pre-Qin view that the movement of talented persons among nations is the key indicator to assess national political power, and he adds that it is “an advance on the current lack of any standard to assess national political power in contemporary international relations theory.”

Given variations in the moral levels of states and the quality of leaders and advisors, there will also be variations in the national power of states. Hence, pre-Qin thinking assumes that power in the international system has a hierarchical structure, in contrast to the principle in contemporary relations theory that demands respect for the equality of state sovereignty. Unexpectedly, perhaps, the accounts of pre-Qin thinkers may better model contemporary reality than theories of more modern origin: “If we look carefully at today’s international system, … we will discover that the power relationships among members of the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund are all structured hierarchically and are not equal. The United Nations distinguishes among permanent members of the Security Council, nonpermanent members of the Security Council, and ordinary member states. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have voting structures dependent on the contributions of the members.” Yan does not deny that norms of equality direct state behavior in the international system, and he opposes practices like the traditional East Asian tribute system with China that make no room, however symbolic, for the principle of sovereign equality among nations. But he argues that the principle of hierarchy among states should play a key role in international relations theory, both because it fits the reality of our interstate world and because it helps theorists think about how best to deal with practical political problems, such as minimizing violent international conflict: “Pre-Qin thinkers generally believe that hierarchical norms can restrain state behavior and thus maintain order among states, whereas contemporary international relations theorists think that, to restrain states’ behavior, norms of equality alone can uphold the order of the international system.” Moreover, the case for equality on the ground that it helps to protect the interests of weaker states is not compelling because hierarchical norms can also perform that function: “Hierarchical norms carry with them the demand that the strong should undertake greater international responsibilities while the weak respect the implementation of discriminatory international rules. For instance, developed countries should each provide 0.7 percent of their GDP to assist developing countries, and nonnuclear states must not seek to possess nuclear weapons.”

Pre-Qin international political philosophy also offers insights about how norms are disseminated in the international system. According to contemporary international relations theory, new norms are put forward by major powers, gain support from other states, and are internalized by most states after an extended period of implementation. But “contemporary theory still does not understand the process whereby international norms are internalized. According to the views of the nature of humane authority and hegemony expressed by pre-Qin philosophers, we know that humane authority has the role of taking the lead in implementing and upholding international norms, whereas hegemony lacks this. Based on this realization, we can study the path by which the nature of the leading state affects the internalization of international norms after they have been established.” Yan’s hypothesis is that humane authority is more likely than hegemonic power to succeed in influencing the norms of the international system.

In short, the key to international power is political power, and the key to political power is morally informed political leadership. Yan is a realist, but he believes that states which act in accordance with morality are more likely to achieve long-lasting success in the international realm. States that rely on tyranny to get their way will end up on the bottom of the pile; states that rely on hegemony can end up as great powers; but humane authority is the real key to becoming the world’s leading power. As Yan puts it, “A humane authority under heaven relies on its ultrapowerful moral force to maintain its comprehensive state power in first place in the system.” But Yan also rejects the idealistic view held by pre-Qin thinkers (with the exception of Hanfeizi) that morality alone can determine international leadership: “[A leading state’s] hard power may not be the strongest at the time, but the level of its hard power cannot be too low. … It is unthinkable that a state could attain humane authority under heaven relying purely on morality and hard power of the lowest class. In the international politics of the twenty-first century, the importance of the area of territory ruled has already declined as a factor in gaining world leadership, but a population of more than two hundred million does play an important role.” Without the requisite population, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and Russia “have no possibility of becoming the leading states of the system.” For the moment, India and Indonesia may lack the hard economic and military power. That leaves two states in contention for global leadership: China and the United States. The United States is clearly the leading power now. So what should China do if it wants to take over “first place in the system”?

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHINA’S RISE

Given the importance of political power for international leadership, the Chinese government should not assume that more economic power necessarily translates into the power to shape international norms. As Yan puts it, “an increase in wealth can raise China’s power status but it does not necessarily enable China to become a country respected by others, because a political superpower that puts wealth as its highest national interest may bring disaster rather than blessings to other countries.” Since China undertook its policy of reform and opening in 1978, however, “the Chinese government has made economic growth the core of its strategy.” In 2005, it proposed a policy of a harmonious world and set the goal of building friendships with other countries, “but in August 2008, the report of the Foreign Affairs Meeting of the Party Central Committee again said that ‘the work of foreign affairs should uphold economic construction at its core.’” Yan concludes his analysis of the status quo on a critical note: “The Chinese government has not yet been able consciously to make building a humane authority the goal of its strategy for ascent.” Like contemporary international relations theorists, the Chinese government seems to overestimate the political importance of economic power. In this case, the government may still be under the sway of Marxist economic determinism.

So what should be done instead? Yan proposes that China should learn from Xunzi’s recommendation of strategy for a rising power, which “stresses human talent, that is, it focuses on competition for talent.” Again, there is a critique of the status quo: “At present, China’s strategy of seeking talent is still mainly used for developing enterprises and has not yet been applied to raising the nation as a whole. Talent is still understood as having to do with technicians rather than politicians or high-ranking officials. … The personnel requirements for the rise of a great power are not for technicians but for politicians and officials who have the ability to invent systems or regulations, because a pronounced ability to invent systems and regulations is the key to ensuring the rise of a great power.” Talented people are available but they are not always chosen: “Xunzi thinks that there are many talented people with both morality and ability, and the key is whether the ruler will choose them.”

Drawing on historical examples, Yan puts forward some strategies for finding talent that ensure the rise of a great power. First, “the degree of openness is high: choosing officials from the whole world who meet the requisite standards of morality and ability, so as to improve the capability of the government to formulate correct policies. For example, in ancient times, the Tang Dynasty in China and the Umayyad Empire in North Africa, Spain, and the Middle East, in the course of their rise, employed a great number of foreigners as officials. It is said that at its peak more than 70 percent of officials in the Umayyad Empire were foreigners. The United States has attained its present hegemonic status also by its policy of attracting talented and outstanding foreigners.” Yan is a nationalist—he cares about the good of his country more than that of other countries—but he believes the best way to promote the good of his country is to employ more foreigners. Once China passes a certain baseline of hard power, the main competition with the United States will be competition for human talent rather than for economic or military superiority.

Second, Yan argues that officials should be held responsible for their mistakes. He opposes lifetime job security that increases the risk of officials becoming corrupt, lazy, and prone to repeating mistakes. In the more meritocratic societies, “unsuitable government officials could be speedily removed, reducing the probability of erroneous decisions. This applied to all politicians and officials if they lost their ability to make correct decisions for any reason, such as being corrupted by power, being out-of-date in knowledge, decaying in thought, suffering a decline in their ability to reflect, or experiencing deterioration in health. Establishing a system by which officials can be removed in a timely fashion provides opportunities for talented people and can reduce errors of policy and ultimately increase political power.”

Yan also argues for the establishment of independent think tanks that would provide professional advice on policy. At the moment, “the research institutions attached to our government agencies are not think tanks in the strict sense. Their main task is to carry out policies, not to furnish ideas. To undertake the work of a think tank is to exercise social responsibility.” Such think tanks existed in the past, but “since the founding of the new China in 1949, the state has not allowed high officials to have their own personal advisors or to rely on nongovernmental advisory organizations.” If the think tank system of independent and public-spirited advisors is revived, Yan openly says that he would be willing to serve: “I would take part.”

In short, China can increase its political power by adopting a more meritocratic system of selection of political officials and advisors. But this leads to the question of what exactly these talented and public-spirited politicians and advisors should aim for. In the West, political discourse is usually confined to two options: “good” democracy and “bad” authoritarianism. Pro-democracy commentators, whether hawkish or liberal, put forward proposals for a “community” or “concert” of democracies that would act together to promote democratic development in the world. The social scientific thesis that democracies do not go to war with one another has been the subject of much debate. In Yan’s view, however, the two relevant options are hegemony and humane authority. The former is less good but it secures strategic reliability: countries that pursue hegemony in the pre-Qin sense are reliable international actors, even if they are not always striving for morally admirable goals. Humane authority is the best option—countries that lead with humane authority inspire the rest of the world with their morally superior ways—but it is more difficult to achieve.

So, should China strive for hegemony or humane authority? Yan allows for both possibilities. He regards the United States as a hegemonic power and argues that China should strive for a higher moral standing: “If China wants to become a state of humane authority, this would be different from the contemporary United States. The goal of our strategy must be not only to reduce the power gap with the United States but also to provide a better model for society than that given by the United States.” Nonetheless, he also writes in favor of the pursuit of hegemony: “China can reflect on the alliance-building strategies of The Stratagems of the Warring States and adopt a strategy beneficial to expanding its international political support. The alliance-building strategies of The Stratagems of the Warring States and the Communist Party’s United Front principle are very similar. This kind of principle was able to bring about victory in the War against Japanese Aggression [i.e., World War II], and it may also be successful in guiding China’s rise.” We can infer that China’s aims would depend on the international context. In time of war, it should strive to build reliable alliances to maintain or increase its hegemonic status. In time of peace, it should strive to act like a humane authority.

But how can China act like a humane authority? In the pre-Qin era, the political ideal of humane authority was premised on the assumption that there would be one single ruling authority with sovereignty over the whole world. According to Yan, however, the ideal of world government is neither feasible nor desirable today. So how could China act like a humane authority in a hierarchical world divided into states that often have competing interests? In international relations, it should do as it says: “China should not adopt the United States’ current way of acting, saying that all states are equal while in practice always seeking to have a dominant international status.” The Chinese government also has resorted to some hypocrisy: “China’s proposal for democratization of international relations has not been easily accepted by the international community because China could not abandon its special veto power in the United Nations Security Council.” Instead, China should openly recognize that it is a dominant power in a hierarchical world, but this sense of dominance means that it has extra responsibilities, including the provision of economic assistance to poor countries and security guarantees to nonnuclear states. Rather than insisting on reciprocity with weaker states, China should try to gain their support by allowing for differential international norms to work in their favor. In the cooperation of the 10 + 1—the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China—for example, “China is required to implement the norm of zero tariffs in agricultural trade before the ASEAN states do. This unequal norm enabled the economic cooperation of the 10 + 1 to develop more rapidly than that between Japan and ASEAN. Japan’s demand for equal tariffs with ASEAN slowed the progress of its economic cooperation with the ASEAN states, which lags far behind that of China and ASEAN.”

But it’s not just a question of foreign policy: “For China to become a superpower modeled on humane authority, it must first become a model from which other states are willing to learn.” In other words, China must act like a humane authority at home. Yan argues that the modern equivalent of humane authority is democracy: “I think that in their respect for norms, the modern concept of democracy and the ancient Chinese concept of humane authority are alike. … The electoral system has become the universal political norm today.” Humane authority would also translate into a society that is more open to the rest of the world: “Stricter border controls lead to greater suspicion between nations and more pronounced confrontation. China should promote the principle of freedom to travel, to live, and to work anywhere in the world. People tend to move to the better place, and thus nations with better conditions will be attractive to talented people. Hence, China should expand its policy of opening to international society.”

In appendix 2, Yan portrays himself as a hard-nosed scientific realist: “I am more concerned with how real life and real political behavior can verify explanatory theory. I do not like what cannot be verified, because there is no way of knowing if its conclusions are valid. For instance, in making predictions I like to set a timeframe: within five years, or within three years.”4 Yet his discussion of the “ultrapowerful moral force” of humane authority does seem to veer into normative thinking about a distant future. It’s hard to disagree with his inspiring political vision for China: it would take on extra international responsibilities and help marginalized countries; its rulers would be chosen by some sort of electoral system; their political advisors would be chosen according to a meritocratic system that ensured promotion and demotion according to performance rather than political loyalty; and China’s borders would be open for peoples of all nationalities to join the competition to attract talent. This vision does, however, seem quite far removed from the current reality. But maybe we can forgive a bit of methodological inconsistency. If America’s most influential realists can dream of a world without nuclear weapons,5 then Yan Xuetong can dream of a country that inspires the rest of the world with its humane values.