![]()

Xunzi’s Interstate Political Philosophy and Its Message for Today

Xunzi (ca. 313–238 BCE) was a famous thinker from the Warring States Period. There have been many in-depth studies of his philosophy in the light of the history of thought in China, but in the political arena the majority of such studies examine his view of domestic administration; very few scholars have examined Xunzi’s ideas from the perspective of international politics.1 What Xunzi has to say about international politics is found scattered throughout his writings but is largely concentrated in three chapters: “Humane Governance,” “Humane Authority and Hegemony,” and “Correcting: A Discussion.”2 Although what Xunzi has to say about international politics cannot strictly be called a theory in the full sense of that term, yet from the ideas he set out more than two thousand years ago it is possible to explain aspects of modern international politics.3 This implies that some of his ideas must be quite reasonable. This essay looks at Xunzi’s interstate political philosophy from the perspectives of methodology, the basic concepts of international politics, and the strategy for China’s rise.

METHOD OF ANALYSIS

Analysis of Individual Entities and on the Level of the Individual

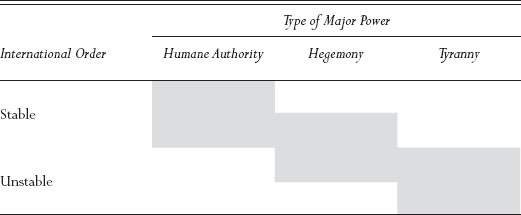

International actor and international system are two important analytical variables in contemporary international relations theory. To explain the phenomenon of international politics by means of changes of actor is called “individualistic analysis”; to explain the same phenomenon by means of changes in the international system is called “holistic analysis.” Although Xunzi does discuss interstate norms (rites) and the system of Five Services as a means of preventing international conflict, yet since his thought is grounded in the premise of the unity of the whole world, he discusses how to implement a stable international order from the viewpoint of the policy of major powers. Xunzi thinks that major powers are the cause of the success or failure of stability in the international system but the international system cannot change the behavior of major powers. He begins by analyzing the conditions under which states rise, fall, and collapse, and then brings together the causes of change in the international order. In his analysis, order and disorder serve as the two values of the dependent variable, interstate order. Sage king (or humane authority), hegemon (or hegemony), and tyrant (or tyranny) serve as the three values of the independent variable, the nature of the state.4 In the Xunzi, as verbs wang (to be a sage king) means “to lead the world”; ba (to be a hegemon) means “to dominate the world,” and qiang (to be a tyrant) means “to be stronger than other states.” As nouns, the three terms refer to states or their leaders who undertake these respective actions. Xunzi sees the character of the state, the type of ruler, and the nature of policy as three aspects of the same thing, holding that these three are all of a piece. The degree of stability of international order is determined by the nature of the world’s major powers. He concludes that if the world’s major powers are ruled by sage kings or hegemons, then the international order is stable; if by tyrants, then it is unstable. If the great power is a hegemon, then even though it enjoys stable relationships with its allies there is instability in relations with countries outside the alliances (see table 2.1).

An established methodology for studying international relations theory is what is known as the levels of analysis. The three levels of analysis in international studies are: system, organization and individual. Xunzi’s analysis belongs to that of the individual. In his analysis, the state is a mediating variable and the ruler is the most basic independent variable. He thinks that the state is a tool with which the ruler can administer society. Differences in the ruler’s morality and beliefs result in different principles and policies in running the state and hence in different types of state. The differences in morality of the rulers of the world’s major powers lead to a difference in the nature of their states, and this in turn determines whether the international order is stable. He says, “The state is the most important instrument for ruling all under heaven. The ruler holds the most important position under heaven. If you find the way to hold it, then there is great peace and great glory, and the source of all that is praiseworthy. If you do not learn the way to hold it, then there is great danger, and a great accumulation of such dangers means that it would be better not to have the state than to have it.”5

International Order in Relation to the Nature of Major Powers

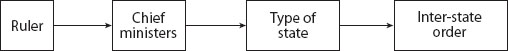

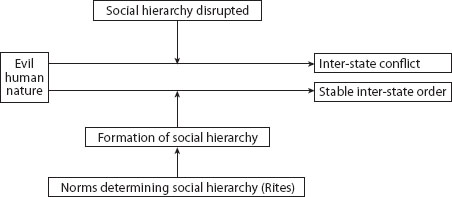

Xunzi’s analysis of individuals is not limited to the ruler alone; he also emphasizes the role of the chief ministers. In his analysis, the chief ministers and the nature of the state are equally important mediating variables. The chief ministers are a mediating variable coming between the ruler and the nature of the state (figure 2.1). He believes that the core role of the ruler is not to administer the state himself but to choose chief ministers who will do this. He says, “One who holds the state must not administer it alone, since strength and weakness, glory and shame lie in choosing chief ministers. An able person with able chief ministers may be a sage king. Someone who is not able but knows and is fearful because of it yet seeks able persons may be a powerful ruler. Someone who is not able and who does not know that he should be fearful and does not seek able persons, but surrounds himself with flatterers, hangers-on, and favorites, is in such danger that, at its most intense, the state falls.”6

Figure 2.1 Policy makers and interstate order

In comparing the two variables of the ruler and the chief ministers, Xunzi thinks that the role of the ruler is decisive because the mediating variable of the chief ministers changes along with changes in the type of ruler. Xunzi thinks that worthy ministers are not rare, but the important question is whether the ruler is able to use them. There are many kinds of chief ministers, but the decisive factor is what type the ruler employs:

Hence, King Cheng, with regard to the duke of Zhou, was such that the king went along with whatever the duke suggested since he knew the duke was of value. With regard to Guan Zhong, Duke Huan employed him in all the affairs of state, since he knew he was of benefit. The state of Wu had Wu Zixu, but he was not used and the state was brought to its knees, losing the Way and losing the worthy. Therefore, one who honors sages may attain humane authority; one who honors the worthy may attain hegemony; one who respects the worthy will survive, whereas one who slights the worthy will perish. From old times until now it has always been the same.7

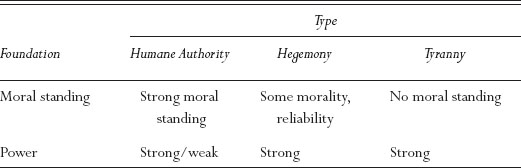

Conceptual Determinism and Internal Causal Determinism

International political theory may be categorized into three groups: materialist determinism, conceptual determinism, and a combination of the two. In general, realist theory is materialist determinism, seeing the hard power of a state as the determining factor; constructivist theory is classical conceptual determinism, seeing human ideas as the determining factor. Institutionalist theory adapts from both of these, holding that material strength and organizational norms are of equal importance. Xunzi does not deny the importance of material power but his method of analysis is the same as that of constructivist theory, seeing concepts as the original motivation for all conduct. The difference between him and the constructivists is that his independent variable is the personal concept of the ruler and the chief ministers, whereas constructivism stresses that the independent variable is the concept of society as a collective. In discussing norms of action, Xunzi uses the three terms humane authority/sage king, hegemony/hegemon, and tyranny/tyrant. These are somewhat similar to Alexander Wendt’s use of Kantian culture, Lockean culture, and Hobbesian culture. Xunzi says, “Humane authority wins over the people; hegemony wins over allies; tyranny wins over territory.”8 This means that emperors and kings compete for talented people, hegemons compete for neighboring allies, and the rulers of great powers compete for territory. Xunzi thinks that to win over talented people requires morality; to win over allies requires sincerity and credibility; to win over territory requires strength. Wendt thinks that the three different types of cultural structure—Kantian, Lockean, and Hobbesian—are international norms that differ, being grounded in legitimacy, cost, and power.9 If we compare these two sets of concepts we find that humane authority and tyranny are similar to Kantian and Hobbesian culture, respectively, but hegemony is not very much like Lockean culture.

Xunzi sees the cause of change in a state’s status as dependent not on the ability of the ruler and chief ministers but on their ideas. He thinks that the various ideas of the ruler lead him to choose chief ministers who reflect the new political principles leading to different results and hence changes in a state’s status: “Those who follow the principle of humane authority and work with subordinates of humane authority can then attain humane authority; those who follow the principle of hegemony and work with subordinates of hegemony can then exert hegemony; those who follow the principle of a failed state and work with subordinates of a failed state will fail.”10

Since Xunzi sees the ideas of the ruler and chief ministers as the original driving force for state conduct, his method of analysis is that of internal causal determinism. “One suitably prepared will be a sage king; one suitably prepared will be a hegemon; one suitably prepared will survive; one suitably prepared will perish. In the use of a state of ten thousand chariots, the wherewithal to establish its authority, the wherewithal to embellish its renown, the wherewithal to overcome its enemies, and the wherewithal to determine security or danger for the state all depend on oneself, not on others. To be a sage king or a hegemon, to be secure or in peril and perish, all are determined by oneself, not by others.”11 This means that the ruler’s type of political achievements depends on the conditions he has prepared.

Rigorous Analysis and Comparative Analysis

All international political phenomena are the result of many factors coming together. Depending on the number of independent variables that are chosen for the analysis, analytical methods may be separated into rigorous analysis or comprehensive analysis. Comprehensive analysis involves joining together several variables to explain the changes of the dependent variable, but not examining the relationships among the joined variables. Unlike comprehensive analysis, rigorous analysis refers to the use of a single variable to explain the logical causal relationship between independent and dependent variables. For instance, Kenneth N. Waltz explains the presence or absence of war in the international system in terms of the independent variable of the power structure of major states. This is an example of rigorous analysis. Hans J. Morgenthau explains the changes in the international system according to many independent variables such as power, military strength, economic profit, culture, law, morality, and diplomatic strategies. This is an example of comprehensive analysis.

Xunzi’s method of analysis is rigorous rather than comprehensive. He treats the ideas of the ruler as the most basic independent variable and explains this as determining the type of chief ministers who will implement state policies; he uses the type of chief minister to explain the type of state, and then uses the type of state to explain whether there is international stability (see figure 2.1). If we refine his analytical logic, we arrive at figure 2.2. We can add policy direction as a mediating variable between the chief ministers and the type of state, and state power and foreign relations between type of state and interstate order. In Xunzi’s thought, variables at different levels have clear logical relationships and these logical relationships are consistent.

Figure 2.2 Relationships of variables at different levels

Comparative analysis contrasts with case analysis. Single-case analysis refers to giving arguments in support of a thesis based on a particular case, whereas comparative analysis relies on using different cases to illustrate the pros and cons of an argument. Xunzi habitually uses cases from each side to discuss a point, and thus his method is that of comparative analysis. The examples he quotes most often in support of his thesis are King Tang of the Shang, the duke of Zhou, and King Wen of Zhou. The counterexamples he chooses are Jie of the Xia and Zhòu of the Shang. For example, in discussing whether humane authority is seized or naturally accrues to its incumbent, he says,

Tang and Wu did not seize all under heaven. They practiced the Way, carried out justice, worked for the common good of all under heaven, and removed the common ills of all under heaven so all under heaven accrued to them. Jie and Zhòu lost all under heaven. They acted contrary to the virtue of Yü and Tang, muddled the distinctions of rites and norms, acted like birds and beasts, accumulated evil, and gave full rein to wickedness and all under heaven left them. That to which all under heaven accrues is called “humane authority”; that which all under heaven deserts is called “death.”12

This means that no ruler can seize world leadership. World leadership will automatically come to those who do sufficient good for people and depart from those who commit evil.

Although Xunzi’s understanding of interstate politics is quite markedly logical, according to the standard of modern science his analytical method is not scientific. His way of quoting examples to justify his arguments is not done well according to scientific positivism. Many of the examples he chooses come from historical legends. They lack any time for the events, background, or basic account and there is no way of ascertaining their authenticity. Moreover, his examples lack the necessary variable control and his way of using examples is by simple case-selection. Although this method is frequently used in modern international relations theory, its scientific value is poor. It is weak in terms of his powers of confirmation and persuasion.

STATE POWER

The Dual Nature of the State as Actor and Tool

In Xunzi’s writings the term state sometimes refers to a political unit and sometimes indicates a tool of the ruler. This usage is basically the same as in contemporary politics. From the perspective of international politics, the state is an international actor, but from the perspective of domestic politics, the state is the tool by which the ruler rules the people.13

Xunzi distinguishes between the state of the Son of Heaven and those of the feudal lords, depending on the greatness of their power: “Of old, the Son of Heaven had a thousand officials whereas the feudal lords had a hundred. One who employed these thousand officials to make his writ run among the states of the feudal lords was called ‘sage king’; one who employed those hundred officials to make his writ run within his own boundaries—even though the state was not secure, yet at least it would not change hands and be abolished—was called ‘prince.’”14 In this passage the term state refers to a political unit. The state of the Son of Heaven was a royal state, however, and its territory and strength far exceeded those of the feudal states; thus, its power was greater than that of the feudal states.

From the point of view of function, Xunzi thinks that the state is a political tool: “The state is a big instrument under heaven and entails heavy responsibility. One may not but carefully choose people to deal with it and then run it. Placing it in risky hands will only lead to danger.”15

The Relationship of Political Strength to Military and Economic Strength

Xunzi’s view of the roles of political strength, military strength, and economic strength and the relationships among them is rather unlike that held nowadays. Today it is generally held that economic strength is the basis of political strength, but Xunzi holds the opposite view. He thinks that political strength plays a role as the basis for economic and military strength. He believes that whatever the strength of one’s economic or military might, they are meaningless without the foundation of political strength. This idea of Xunzi is similar to that of the former CIA chief analyst Ray S. Cline (1932–2009), who formulated the equation that expresses the relationships among the components of comprehensive national power. According to Cline’s equation, Pp = (C + E + M) × (S + W).16 Comprehensive national power is the product of both soft and hard power, so if soft power is zero, then comprehensive national power will also be zero and hard power will be unable to play any role. Xunzi says,

King Wen obtained the Way and with a territory of less than a hundred square kilometers he united all under heaven. Jie and Zhòu lost the Way. They held power over all under heaven but could not enable an ordinary person to live till old age. Hence, for one who is good at using the Way, even if he has a state of less than a hundred square kilometers, that suffices to be independent. For one who is not good at using the Way, even if had a country like Chu of three thousand square kilometers, he would be put into servitude by his enemies.17

The history of the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 can help us to understand why Xunzi thinks that political strength is the foundation of military and economic strength. When the Soviet Union broke up, its military strength was equal to that of the United States and its economy ranked third in the world. But when the Soviet government lost people of ability because of its internal and external politics, its hard power was unable to exercise any role in ensuring the survival of the nation.

Xunzi also thinks that political strength is the basis for the growth of hard power. Xunzi holds to moral determinism; hence, he believes that the key to the success or failure of a state is whether the state’s policy is correct. When the policy is correct, state power will increase, but when it is incorrect, it will diminish:

If the top leader does not value the rites, then the army will weaken; if the top leader does not love the people, then the army will weaken; if one is not faithful in what one has promised, then the army will weaken; if rewards and payments are not plentiful, then the army will weaken; if the generals and commanders are incapable, then the army will weaken. If the top leader has a penchant for exploitation, then the state will be impoverished; if the top leader has a penchant for profit, then the state will be impoverished; if the officials and great ministers are numerous, then the state will be impoverished; if craftsmen and merchants are numerous, then the state will be impoverished; if there are no constraints on undertakings, then the state will be impoverished. … Thus, in the time of Yü there was a decade of floods and in the time of Tang seven years of drought but there was no famine under heaven. After ten years the harvest was plentiful again and there was more than enough. There was no other reason for this but that they understood the beginning and end and the origin and course of events.18

The tripartite separation of powers in the United States, the Meiji Restoration in Japan, and the socialist system of the Soviet Union are all political factors that resulted in a rapid increase of national power for the nations concerned. This modern history helps us to understand Xunzi’s idea that political strength is the basis for a growth in hard power.

Xunzi thinks that a state’s political system is the basis that ensures whether a state’s economy can develop rapidly. This idea is the exact opposite of that which holds that the economic level is the basis for a political system. He says, “Hence, one who restores the rites attains humane authority; one who works at politics becomes strong; one who wins over the people is secure; one who hordes wealth perishes. Thus the one who is a sage king enriches the people; the one who is a hegemon enriches the officials; a state that will survive enriches the great ministers; a dying state enriches its coffers and fills its storerooms.”19 In 1978, China adopted the policy of reform and opening to replace the previous political guideline based on class struggle, and its economy developed rapidly. This part of history helps us to understand Xunzi’s idea that political policy is the basis for growth of economic strength.

Xunzi also thinks that the political principle of foreign policy is the basis for guaranteeing state security. He thinks that state security is not wholly dependent on the size of military force, but is also determined by whether at the political level a state is able to maintain reasonable relationships with others:

If you want to deal with the norms between small and large, strong and weak states to uphold them prudently, then rites and customs must be especially diplomatic, the jade disks should be especially bright, and the diplomatic gifts particularly rich, the spokespersons sent should be gentlemen who write elegantly and speak wisely. If they keep the people’s interests at heart, who will be angry with them? If they are so, then the furious will not attack. One who seeks his reputation is not so. One who seeks profit is not so. One who acts out of anger is not so. The state will be at peace, as if built on a rock, and it will last long like the stars.20

In the 1960s, China adopted a policy of opposition to the two hegemonic powers, the Soviet Union and the United States. But in the early twenty-first century, China has adopted the policy of living harmoniously with its neighbors. In the 1960s, China fought with the United States in Vietnam in the south, and in the north the Soviet army put pressure on the border, whereas in the early twenty-first century China maintains normal relations with major powers such as the United States and Russia (which is the successor after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991). China’s security today is much better than it was in the 1960s. This historical comparison helps us to understand Xunzi’s idea that the principle of foreign policy is the basis for state security.

Xunzi thinks that political strength plays a greater role than economic strength in diplomatic conflicts. He thinks a policy of economic bribery is ineffective in interstate relations. Rather, the most effective means is to use proper conduct to win over other states:

If you serve them with wealth and treasure, then wealth and treasure will run out and your relations with them will still not be normalized. If agreements are sealed and alliances confirmed by oath, then though the agreements be fixed yet they will not last a day. If you cut off borderland to bribe them, then after it is cut off they will be avaricious for yet more. The more you pander to them, the more they will advance on you until you have used up your resources and the state has been given over and then there is nothing left. … Thus the intelligent prince does not do so. He must restore rites so as to unify his court, correct law so as to unify his officials, be even in governing so as to unify his people, and then customs will be unified in court, the various affairs will be unified under the officials; the mass of ordinary people will be unified along with him. If you do so, then those close by will compete for affection and those far away will want to draw near. The whole country will be of one mind. The three armies will join their strength together. Your reputation will be such as to overawe them and your authority strong enough to goad them. They will come and bow down to you and accept your direction. No strong or violent state will not send ambassadors to you, like in the fight between Wu Huo [a giant] and Jiao Yao [a dwarf].21

In 2005, in order to gain a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, the Japanese government spent sixteen billion U.S. dollars buying votes from developing countries but still failed to win a seat.22 In 1971, the United States opposed the United Nations granting China’s seat to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). At the time, American aid to third world countries far exceeded Chinese aid. Nevertheless, with the help of friendly countries in Africa, the PRC successfully acceded to the China seat at the United Nations that year. These two historical examples help us to understand Xunzi’s idea that in foreign affairs political strength is more useful than economic strength.

The Principle of Uneven Development of Power

Xunzi thinks that an important reason why one’s own state can be strong is that the administration of other states is a failure: “Others accumulate faults daily; we become more perfect every day. Others become poorer daily; we become richer every day; others are overloaded with work daily; we have more and more leisure every day. In the relations between prince and ministers, people of high and low status, others draw daily further and further apart while we grow closer and closer every day. One acts correctly while others make mistakes. One who makes his own state act correctly will attain hegemony.”23 This view of Xunzi is very similar to the idea of relative power in contemporary international relations theory. Because the power status of a state in terms of strength is relative to that of other states, a state’s relative advantage relies on its increasing the gap between its own strength and that of others. Nevertheless, an important factor accounting for the increasing gap is the decline of the other state. If the increase in strength of all states was equal, then their relative strengths would not change.

Xunzi also says, “The states of others are all in a mess and my state alone is well-ordered. Others are in danger and I alone am safe. Others have lost their states; I arise and administer them. Therefore, in using the state the benevolent person does not rely only on his own state; he must also conquer the will of people in other states.”24 Xunzi is not opposed to annexation but he thinks that different kinds of annexation yield different results. He thinks that morally correct annexation can increase strength whereas immoral annexation will decrease strength: “One who uses virtue to annex others will attain humane authority; one who uses might to annex others will become weak; one who uses riches to annex others will become poor. From of old until now it has always been the same.”25

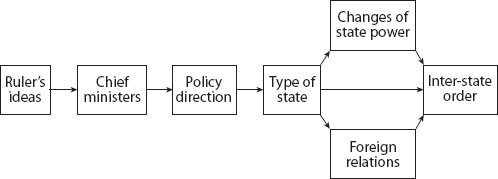

Guided by conceptual determinism, Xunzi attributes the cause of uneven development of state power to different ideas on the part of the rulers. He says, “Speaking of ministers, there are flattering ministers, usurping ministers, efficient ministers, and sagacious ministers. … [T]hus by using sagacious ministers one can attain humane authority, by using efficient ministers one can be strong, by using usurping ministers one is in danger, and by using flattering ministers one will perish.”26 Based on this statement, we can extrapolate the logic of the relationship between rulers and ministers. Changes in the status of state power arise from state policy, which is formulated by high-ranking officials. Choice of these ministers is determined by the ideas of the ruler (see figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Causes of uneven development of power

Xunzi says, “There is no lord of men who does not want to be strong and does not hate weakness, who does not want to be secure and does not hate danger, who does not want renown and does not hate shame. This is what Yü and Jie held in common. To fulfill these three desires and avoid the three ills, what way is the most appropriate? I say: ‘prudently choose your prime minister; there is no other way than this.’”27 Xunzi also summarizes the experience of the extinction of states in history: “In the past there were ten thousand states, and now there are fewer than a hundred. There is no other explanation for this; they did but fall away from this [a careful choice of ministers].”28

Because Xunzi thinks that the choice of the type of officials employed is directly related to the rise and fall of state power, he sees the choice of people as the core of a strong state’s strategy: “If you wish to harmonize all under heaven and restrain Qin and Chu, there is nothing better than employing intelligent and exemplary persons. They easily use their knowledge and wisdom. They do not overwork themselves at their tasks but their accomplishments and fame are very great. They work easily and happily; hence the perspicacious prince treats them as a treasure, whereas the foolish one finds them difficult.”29 Xunzi also proposes the principle of talent, which does not distinguish between noble and mean in choosing worthy people: “Why can the lord not open positions to talent broadly, neither favoring relatives nor being partial to noble persons, but only seeking those who are able? If he does this, then the ministers will perform their tasks with ease and give precedence to the worthy and happily follow their directions. In this way there could still be a Shun or a Yü and the royal career could rise again. If you want your efforts to unite all under heaven, your renown must equal that of Shun and Yü; what could be more joyful or more praiseworthy than this?”30

Xunzi’s understanding of shifts in state power is a classic case of having an intelligent prince and worthy aides. It is this understanding that leads him to the conclusion that political talent is the key to a state’s strength. On this point his view is basically the same as that of China’s ancient political philosophy, which sees regulations as determined solely by human beings and does not see the system of democratic election as having the inherent capacity to remove unsuitable people. In Xunzi’s time, people had not yet realized that political system creativity is a basic factor affecting changes of status in state power.

Since Xunzi makes unifying the world the highest political goal of the prince, he is not unconditionally opposed to states pursuing a policy of annexation. He assesses the correctness of annexation according to the nature of the annexation. This idea is manifestly incompatible with international norms since World War II. He rather exaggerates the role of political power with regard to state security. Even if a small state upholds a moral foreign policy, it will be hard to avoid large states having ambitions to invade it. In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, which is a typical example of this.

INTERNATIONAL POWER PERSPECTIVE

Contemporary international relations theory discusses three aspects of international power: first, the nature of power relationships, that is, whether relationships among states are cooperative, competitive, or confrontational; second, the grade of power, that is, whether it is dominant, subordinate, or participatory; and third, the content of power, that is, to which area a state’s power belongs: political, economic, or military. Xunzi’s discussion of state power concentrates mainly on the character of power, a topic that is very seldom addressed in contemporary international relations theory.

Definitions of “All under Heaven” and “Possessing All under Heaven”

The idea of “all under heaven” is the basis for Xunzi’s analysis of the nature of state power. Clarifying this concept is helpful for understanding his ideas of the three types of international power: humane authority, hegemony, and tyranny.

He thinks that “all under heaven” is the whole world and that “possessing all under heaven” amounts to having world leadership. This kind of power is the result of the masses and the various feudal states willingly accepting the leadership of the sage. It is not a status that the ruler can win by violence: “All under heaven is the heaviest burden there is; unless one is very strong one cannot bear it. It is huge; unless one is very clever one cannot administer it. Its people are many; unless one is very perspicacious one cannot keep them in harmony. None but a sage can manage to perform these three tasks properly. Hence none but a sage can be a sage king. … All under heaven is so huge that none but a sage may possess it.”31 Xunzi rejects the idea that Jie and Zhòu possessed world leadership: “A popular saying goes that ‘Jie and Zhòu possessed all under heaven; Tang and Wu usurped and took it.’ It is not so. That Jie and Zhòu had the title of Son of Heaven and that the title of Son of Heaven was theirs is correct, but to say that all under heaven was Jie’s and Zhòu’s is not correct.”32 Here he denies the popular saying that the kings Tang and Wu usurped world leadership from Jie and Zhòu, respectively. He thinks that it is correct to say that Jie and Zhòu had the title of leader of the world, but it is wrong to say that they possessed world leadership.

Xunzi holds that the title of world leadership and world leadership itself are two different things:

The sons of a sage king are his children. They have the legitimacy to inherit the position of a sage king after his death as well as the ancestral house of all under heaven. If they are incompetent or improper, however, then internally the ordinary people will detest them and externally the feudal lords will rebel against them; close at hand there will be no unity within the domain and far away the feudal lords will not obey. Commands will not run within the domain. Furthermore, the feudal lords will invade and attack them. If it is like that, then even if they do not perish, I say that they do not possess all under heaven.33

Between 2002 and 2010, the Afghan government ruled Afghanistan in name, but in practice its authority was restricted to the capital, Kabul. Even though this example is not one of world leadership, it can help us to understand what Xunzi has to say about “possessing all under heaven.”

Xunzi thinks that state power and world leadership are different. He holds that state power can be seized but world leadership may not be; rather, it automatically accrues to the appropriate person: “It is possible for a state be stolen from others, but it is not possible for all under heaven to be stolen from others. It is possible for states to be annexed, but it is not possible for all under heaven to be annexed.”34 At the beginning of World War II, the military and economic power of Nazi Germany rose considerably and the expansion of its armies outward increased Germany’s power over world affairs, but Germany was not able to rely on this to gain international leadership; instead, it increasingly became the enemy of many countries. This experience from history can help us to understand Xunzi’s distinction between the ruling power of a state and leadership of the world (all under heaven).

Humane Authority Founded on Political Morality

Xunzi thinks that humane authority is the highest form of world power. Its foundation is the morality of the ruler of a kingdom (the Son of Heaven): “Thus it is said: by practicing justice in their states, their fame spread in a day. Such were Tang and Wu. Tang had Bo as his capital, King Wu had Hao as his capital; both were only a hundred square kilometers, yet they unified all under heaven and the feudal lords were their ministers; among those who received their summons there were none who did not obey. There was no other reason for this but that they implemented norms. This is what is called ‘establishing norms and attaining humane authority.’”35 This is to say that the superior morality of King Tang of the Shang and King Wu of the Zhou were such that they could attain leadership of all under heaven based on the small cities of Bo and Hao, respectively. The religious authority of the Vatican is rather like what Xunzi says about humane authority. The territory of the Vatican is even smaller than that of Singapore and its economic might is not up as great as Singapore’s. Moreover, it has no army. Nevertheless, the Vatican’s authority in world affairs is far beyond Singapore’s. This example can help us to understand why Xunzi thinks that morality is the foundation for attaining leadership under heaven.

Xunzi thinks that people who possess humane authority do so because they implement moral norms. Speaking of the sage king, he says,

Unlike others, his benevolence stretches to all under heaven; his justice to all under heaven; his authority to all under heaven. Since his benevolence stretches to all under heaven, there is no one in all under heaven who does not love him. Since his justice stretches to all under heaven, there is no one in all under heaven who does not respect him. Since his authority stretches to all under heaven, there is no one in all under heaven who dares oppose him. Relying on the authority of invincibility and a policy of winning people’s support, one can win victories without wars, acquire without attacking. Troops in armor are not sent out and yet all under heaven submits. This is the man who knows the humane way of leadership.36

Since Xunzi thinks that humane authority is founded on the superior morality of the ruler himself, he thinks that only a sage can possess humane authority: “The sage is someone who possesses the Way and is perfect all round and who is the standard for judging the authority under heaven.”37 We would have difficulty finding a political leader who meets Xunzi’s standard, but if one compares Franklin Delano Roosevelt as president of the United States during World War II and the recent George W. Bush, we can see what Xunzi means about the moral power of the leader playing a role in establishing international norms and changing the international system. Roosevelt’s belief in world peace was the impetus for the foundation of the United Nations after World War II, whereas Bush’s Christian fundamentalist beliefs led to the United States continually flouting international norms, which resulted in a decline of the international nonproliferation regime.

Hegemony Based on Hard Power and Strategic Reliability

Xunzi thinks that hegemony is a lower form of international power than humane authority. Humane authority is something that other states are willing to accept as their leadership under heaven, whereas hegemony is interstate domination when the ruler’s moral level falls short of that required for humane authority and when he attains interstate leadership by great force and strategic reliability. Humane authority naturally accrues to a sage but hegemony can be gained only by the ruler’s striving for it.

Xunzi thinks that even though hegemony is a lesser form of interstate power than humane authority yet attaining hegemony is not easy. Even though the moral level of the hegemon is not as high as that of humane authority yet it must at least reach the level of being strategically reliable. In other words, one cannot attain hegemony by trusting to hard power while lacking strategic reliability. When describing hegemony, Xunzi says,

Although virtue may not be up to the mark, nor were norms fully realized, yet when the principle of all under heaven is somewhat gathered together, punishments and rewards are already trusted by all under heaven, all below the ministers know what they can expect. Once administrative commands are made plain, even if one sees one’s chance for gain defeated, yet there is no cheating the people; contracts are already sealed, even if one sees one’s chance for gain defeated, yet there is no cheating one’s partners. If it is so, then the troops will be strong and the town will be firm and enemy states will tremble in fear. Once it is clear the state stands united, your allies will trust you. Even if you have a remote border state, your reputation will cause all under heaven to quiver. Such were the Five Lords. Hence, Huan of Qi, Wen of Jin, Zhuang of Chu, Helü of Wu, and Goujian of Yue all had states that were on the margins, yet they overawed all under heaven and their strength overpowered the central states. There was no other reason for this but that they had strategic reliability. This is to attain hegemony by establishing strategic reliability.38

Xunzi thinks that strategic reliability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for hegemony. Strategic reliability alone cannot ensure that one attains hegemony; one also needs a basis in hard power. The ruler of a hegemonic state must win the trust of his allies and must also strengthen his hard power. Only in that way will the allies respect him as a hegemonic lord. When Xunzi describes the hegemons, he says,

They open up wasteland for cultivation, fill their barns and storehouses, make all their preparations, carefully recruit, select, and accept officials of talent and skill, and then reflect on congratulating and rewarding them to advance them, and strictly punishing them to correct them. They save dying states and ensure an inheritance to lines that are dying out. They uphold the weak and forbid the violent, and, since they have no mind for annexation, the feudal lords love them. They practice the way of turning enemies into friends so as to draw closer to the feudal lords and the feudal lords delight in them. … Thus by clarifying their conduct as lacking all desire for annexation, and relying on their way of turning enemies into friends, even when there is no sage king or hegemon, they can always win. These are the men who know the way of hegemony.39

Tyranny Based on Military Force and Stratagems

Xunzi thinks that tyranny is a lesser form of international power than hegemony. This kind of power relies on military force and stratagems. Since the only way for an expanding tyranny to invade the territory of other states is by military force, a state ruled by tyranny will inevitably have many enemies. This implies that tyranny will easily be weakened. Xunzi says,

One who uses brute force will face the defended cities of others and fight with the troops of others, and we will use force to overcome them; hence, injuries to the other’s people will inevitably be serious. When injuries to the other’s people are serious, then the hate of the people of other states against us will inevitably be great. When the hate of the people of other states against us is great, then they will want to fight us every day. Their defended cities fighting with their troops, and our using force to overcome them will all inevitably result in serious injuries to our people. When injuries to our people are serious, then the hatred of our people against us will inevitably be great. When the hatred of our people against us is great, then they will increasingly not want to fight for us. When the people of other states increasingly want to fight us and our people increasingly do not want to fight for us, this is why the formerly strong become weak. Territory will be taken but the people flee, troubles will mount and achievements diminish; even if the land defended increases, the defenders will decrease. This is why the formerly great will be weakened.40

This passage says that the rule of tyranny relies only on force and lacks morality. This type of power inevitably turns everyone else into an enemy; thus it is doomed to perish.

According to what Xunzi has set out about the three forms of interstate power—humane authority, hegemony, and tyranny—we may illustrate their nature and basis as in table 2.2.

In his analysis of the foundations of the three forms of interstate power, Xunzi overlooks the importance of hard power for humane authority. Even if the territories of Bo and Hao ruled by the kings Tang and Wu, respectively, were small, the states of the feudal lords of that time may have been even smaller and weaker. By the Spring and Autumn Period, the scale of states had generally increased in size. Both Qi and Qin were once larger than Chu, and so Chu was not the strongest state at the time. Therefore, when Xunzi uses the example of Chu’s being larger than the lands of the kings Tang and Wu and yet not being able to attain all under heaven to prove that power is not important for humane authority, his argument is less persuasive.

The Foundations of Different Types of Power

The international moral authority of the U.S. president Woodrow Wilson at the end of World War I was very high, and he proposed the very moral Fourteen Point plan and proposed the founding of the League of Nations. But within America, isolationism prevented Wilson from fully participating in international affairs, with the result that after World War I the United States could not attain world leadership. This shows that the moral standing of a leader, though a necessary condition for attaining world leadership, is not a sufficient condition. Lacking strong power or failing to play a full part in international affairs and having only moral authority is not sufficient to enable a state to attain world leadership. Hard power may in fact be equally important for both humane authority and hegemony. Morgenthau notes that the moral norms that restrain savage conflict domestically are invalid in international society. International society and domestic society have two different kinds of moral norms.41 Clearly, Xunzi did not think about any difference in nature between interstate and domestic society and so he held that the norms of domestic society are wholly applicable to the interstate social system.

INTERNATIONAL ORDER

Although Xunzi’s understanding of the role of concepts is like that of constructivist theory, his understanding of interstate conflict and stability is like that of contemporary realist theory. His ideas for preventing interstate conflict and upholding interstate order, however, are like neoliberal theory.

The Human Origin of Conflict

Xunzi holds that human nature is evil. That people strive for gain is a natural social phenomenon. Competition inevitably leads to violent conflict: “Now, the nature of man is such that from birth he tends toward gain. He follows this inclination, and hence competition and rapacity ensue while deference and yielding are discarded. … Now, to follow human nature and go along with human inclinations must lead to competition and rapacity and be concordant with opposition to distinctions and to disrupting principles and so lead to violence.”42 The first principle of Morgenthau’s summary of the six principles of political realism is objective law rooted in human nature: “Political realism believes that politics, like society in general, is governed by objective laws, that have their roots in human nature. … Human nature, in which the laws of politics have their roots, has not changed since the classical philosophies of China, India, and Greece endeavored to discover these laws.”43

Xunzi wrote a special chapter to discuss human nature. He criticizes Mencius’s theory that human nature is good for failing to understand what human nature is:

Mencius says, “Man learns because his nature is good.” I say, “It is not so. Rather it is that he did not yet know human nature, nor did he examine the distinction between human nature and custom. Whatever nature is, is given by heaven and need not be learned or worked for. Rites and norms are produced by the sage and it is possible for men to learn them and they can be accomplished through working. What need not be learned or worked for by man is called human nature; what can be learned or accomplished through working is called custom. This is the distinction between nature and custom.”44

Xunzi thinks that the evil of human nature is the basic cause of interstate conflict, because since human desires are unlimited there is no way to fulfill them with material goods: “When man is born he has desires. Though desires are unfulfilled yet he cannot but seek. If he seeks, and has no limits set, then he cannot but conflict with others. If he conflicts with others there will be disorder, and if there is disorder there will be poverty.”45

The Restraining Role of Social Norms

Xunzi holds that increasing a society’s material wealth cannot solve the problem of conflict among people. He looks to restraining human desires as the way to avoid social conflict. He defines human desires as a reflection of human emotions. He says, “Nature is what heaven provides; emotions are the essence of nature; desires are the reflection of emotions.”46 Based on this understanding of desire, Xunzi thinks that by reinforcing rationality, the “mind,” it is possible to restrain the desires, which are a reflection of emotions, and thus social disorder can be avoided:

Man’s desire for life is strong; man’s hatred of death is strong. Yet people follow life and still choose to die, not because they do not want to live or because they want to die, but because they are not able to live and they are able to die. Therefore, when one’s desires aim to cross the limit and action does not reach the point it is because the mind stops the action. What the mind is able to do is to aim for principle and then, no matter how many the desires are, they will not harm order! If desires are not over the mark and action goes over it, this is the work of the mind. If the mind loses principle, then even if desires are few they will only stop at chaos! Hence, ordering chaos lies in what the mind can do rather than in the desires of the emotions.47

Xunzi thinks that the way to reinforce the Warring States Period thought that the erationality in the mind is to establish social norms (rites). He wrote a special chapter discussing what “rites” are: “Rites are what direct the administration. To administer without rites is for administration to fail to run. … Rites are to directing a state as scales are to light and heavy, as the inked cord is to crooked and straight. Hence, without rites human beings cannot live and without rites affairs cannot be accomplished and a state without rites is not at peace.”48 This is to say that rites are the norm for directing politics. If one does not deal with political affairs according to norms, then they will not be settled. Since he believes that the norms are present in the human mind, Xunzi holds that it is possible to restrain human nature via the norms in the mind: “Now, human nature is evil and it must be corrected by teachers and the model. Once rites and norms are obtained, then it can be ordered. Today people have no teachers or models and they incline to wrongdoing and are not correct. They have no rites or norms and so they are recalcitrant and disordered.”49 This means that human behavior is conditional on the mind being educated or constrained by social norms.

Xunzi explains how interstate norms can restrain state behavior from the perspective of a balance of supply and demand and how violent conflict can then be avoided and international order upheld. He thinks that norms in the mind can rationalize human desires and also increase the level of satisfaction. In other words, when human desires decrease and the capacity for satisfaction increases, then it is easier to attain a balance between them. Xunzi says, “The early kings hated disorder and so established rites and justice to distinguish people, to cultivate human desires, and to provide for what human beings sought, such that desires would not outstrip things and things not fall short of desires. The two together supported each other and grew up, and this is whence rites arose.”50

Xunzi’s ideas about how to use norms to prevent interstate violent conflict has points in common with contemporary neoliberalism, since both hold that norms are to be found in the human mind and that the norms in the human mind can control people’s selfish pursuit of their own interests. Referring to agreements relating to trade and nuclear weapons, Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye say, “All these regimes were designed to resolve common problems in which the uncontrolled pursuit of individual self-interest by some governments could adversely affect the national interest of all the rest.”51 And, “Over time, governments develop reputations for compliance, not just to the letter of the law but to the spirit as well. These reputations constitute one of their most important assets.”52

Hierarchical Basis for Social Norms

Xunzi thinks that social norms have two roles that help to prevent interstate violent conflict. The first is what has just been outlined in the preceding section, that norms can adjust the balance between desires and levels of satisfaction. The second is to determine classes in society so that people’s conduct will be determined by the class to which they belong and so violent conflict will be avoided. He says, “The life of human beings cannot be without communities. If there are communities without distinctions, then there will be conflict, and if conflict, then disorder, and if disorder, then poverty. Hence, the failure to make distinctions is the bane of human life, whereas having distinctions is the basic good of all under heaven. The ruler is the key to the management of distinctions.”53 When explaining how hierarchical norms are able to prevent disorder in society, he says, “The early kings hated disorder and so they determined the distinctions of rites and norms so that there were classes of rich and poor, high and low status, sufficient so that there could be mutual oversight. This is the root of fostering all under heaven.”54 Norms for distinguishing social classes are the basic way to maintain the stability of all under heaven.

Xunzi thinks that if there were no social classes to repress human beings’ natural desire to seek material goods, then interstate violent conflict could not be avoided. He says,

When distinctions are equal, then there is no sequence. When one grasps hold of equality, then there is no unity. When the mass of people are all equal, then no one can be sent on commission. There is heaven and there is earth and hence up and down are to be distinguished. As soon as an enlightened king holds power, he runs his state with regulations. Two nobles cannot obey each other; two commoners cannot commission each other. This is the setup of heaven. When the powers exercised by two people are equal and their desires are the same, then since goods cannot satisfy them there will be conflict. If there is conflict, there will inevitably be disorder. And if there is disorder, there will be poverty.55

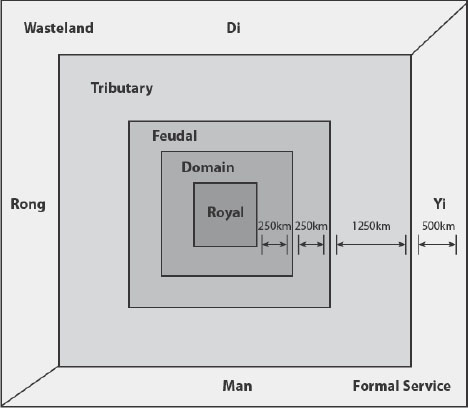

According to the historical experience of the Five Services of the Western Zhou, Xunzi thinks that by relying on the relationship of near and far to establish interstate norms of different grades it is possible to repress interstate violent conflict.56 He thinks that the system of Five Services established by the Zhou was able to uphold the stability of the interstate system under the Western Zhou because this system involves different grades of state undertaking different areas of responsibility and hence this system of norms was effective: “The norms of humane authority are to observe the circumstances so as to produce the tools to work thereon, to weigh the distance and determine the tribute due. How could it then all be equal!”57 This is to say, interstate norms should be designed according to the differences between states rather than be the same for each state. In fact, modern international norms still share this characteristic. The members of the United Nations are classified into three grades: permanent members of the Security Council, nonpermanent members of the Security Council, and ordinary members. The International Monetary Fund allocates the number of votes according to the size of contributions. The World Trade Organization determines the level of tariffs to be paid according to whether one is a developed or developing country. These examples help us to understand how Xunzi sees hierarchical distinctions as a basis for the effectiveness of interstate norms. See figure 2.4, which sets out the logical relationships in Xunzi’s view of human nature, social grades, social norms, and interstate order.

Xunzi describes the Five Services of the Western Zhou as follows:

Therefore, the various Chinese states had the same service and the same customs, whereas the states of the Man, Yi, Di, and Rong had the same service but different regulations. Within the pale was the domain service and outside the pale the feudal service. The feudal areas up to the border area were the tributary service; the Man and Yi were in the formal service; the Rong and Di were in the wasteland service. The domain service sacrificed to the king’s father, the feudal service sacrificed to the king’s grandparents, the tributary service sacrificed to the king’s ancestors, the formal service presented tribute, and the wasteland service honored the king’s accession. The sacrifices to the father were carried out daily, to the grandfather monthly, to the ancestors by season. Tribute was offered once a year. This is what is called observing the circumstances so as to produce the tools to work thereon, weighing the distance, and determining the tribute due. This is the system of humane authority.58

Figure 2.4 The influence of evil human nature and social hierarchy on interstate order

The modern understanding of the system of Five Services is as follows. The states of central China gave the same kind of service to the Son of Heaven and were governed by the same rites and institutions, while the states of other nationalities, though still owing the same service to the Son of Heaven, were governed by different institutions. The feudal lords surrounding the royal capital offered agricultural service. The feudal lords at a distance of 250 kilometers offered service as border guards. The feudal lords from the feudal area to the border area gave tribute at fixed seasons. The task of the minority tribes of the south and east was to pacify the local population. The minority people of the north and west merely had to give tribute at irregular intervals to show that they accepted the leadership of the Son of Heaven. Those responsible for agriculture had to provide offerings for sacrifice every day. Those responsible for security had to provide sacrificial offerings every month. Those responsible for tributary goods had to provide sacrificial offerings every season. Those responsible for keeping their own peace gave sacrificial offerings once a year. Those who merely showed their acceptance of the leadership could give offerings irregulary. The norm of providing offerings at different frequencies was made according to geographics distance from the throne. This is the method of the kings, In figure 2.5, the formal and wasteland services are interpreted as geofraphically distinct area rather than as sequential concentric regions. The ancient Chinese believed that the earth is quadrate and covered by a round heaven.

Figure 2.5 The system of Five Services

Xunzi’s understanding of the causes of war is basically the same as that of realist theory, namely, that international war comes from social anarchy. Xunzi considers only how a hierarchical system can help in reducing interstate conflict, however, and does not consider how changes in the balance of power among states mat also alter the hierarchical relationship in the interstate system. When the balance of power change and the status of a state is not adjusted, then war may break out. The main reason Xunzi fails to discuss how to adjust hierarchical norms so as to adapt to changes in the relative power of states is that he is an internal causal determinist. He considers only how state policy can influence change in state power and does not consider what impact changes in the balance of power have on the conduct of states.

CONCLUSION AND FINDINGS

My main purpose in reinterpreting Xunzi’s interstate political philosophy is less to introduce an ancient author’s view of interstate relations than to learn something relevant to the strategy of China’s present rise.

The Goal of the Strategy of China’s Rise

Xunzi thinks that humane authority is a form of interstate leadership that is higher than hegemony. All under heaven accrues to the sage king by itself and is not seized. This view merits reflection. What kind of superpower does China want to become? A superpower may be a humane state or a hegemonic state. The difference between the two lies not in the greatness of their power but in their moral standings. If China wants to become a state of humane authority, this would be different from the contemporary United States. The goal of our strategy must be not only to reduce the power gap with the United States but also to provide a better model for society than that given by the United States.

The international community increasingly focuses on what kind of superpower China will become. International society clearly does not want China to become like the Nazi Germany or fascist Japan. At the same time, it does not want to see China become another United States. If China becomes another United States, two things could follow: the world could be divided between two hegemonies and there would be a return to the Cold War, or China would replace the United States and the world order would remain unchanged. The international system of humane authority is not perfect, but compared with the present hegemonic system it allows for more cooperation and greater security.

For China to become a superpower modeled on humane authority, it must first become a model from which other states are willing to learn. Scholars have coined the terms Beijing Consensus and Washington Consensus. In fact, these are two competing models of society. As long as China can build itself up as a country worthy of imitation by others, it will then naturally become a humane state. Since China undertook its policy of reform and opening in 1978, the Chinese government has made economic growth the core of its strategy. An increase in wealth can raise China’s power status but it does not necessarily enable China to become a country respected by others, because a political superpower that puts wealth as its highest national interest may bring disaster rather than blessings to other countries. In September 2005, the Chinese government proposed a foreign policy of a harmonious world and set the goal of building friendships with other countries.59 But in August 2008, the report at the Foreign Affairs Meeting of the Party Central Committee again said that “the work of foreign affairs should uphold economic growth at its core.”60 Two months later, the October meeting of the Tenth Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the Sixteenth Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party again set the building of a harmonious society as the long-term historical task of the socialist state, and proposed social fairness and justice as the basis of social harmony.61 The lack of coordination of these announcements shows that the Chinese government does want to replace accumulation of economic wealth with the building of a harmonious society as its highest political goal but, owing to political inertia formed over the long period during which economic growth has been the core, the Chinese government has not yet been able consciously to make building a humane authority the goal of its strategy for ascent.

The Power Basis of the Strategy for China’s Rise

The Chinese government has already proposed the strategic principle of the road of peaceful development,62 yet whether this strategic principle has as its core increasing resource power or increasing operating power—that is, political power—is not yet clear. At present, the most popular idea in China is that of the basic path of increasing comprehensive national power by developing the economy. If we use Xunzi’s view of political power as the basis for hard power, however, and apply it to the question of comprehensive national power, we find that, since 1949, China first underwent political change before there was an increase in economic development or military power. In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party founded a completely new political system in China and, hence, there was a great increase in comprehensive national power from 1949 to 1956. In 1978, the Chinese government implemented reform and opening-up and so created the historical economic boom of the past thirty years. In 2002, the Chinese government began to implement the policy of balanced development of military buildup and economic construction, with the result that national defense capability rapidly increased.63 In contrast, when the government adopted mistaken political guidelines, such as during the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution, the national economy and military force were seriously diminished.

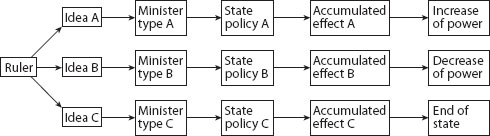

Xunzi’s idea of justice and the current popular notion of soft power are different. The notion of soft power does not differentiate between cultural power and political power, whereas Xunzi’s idea of justice refers to the leader’s ideology and is a matter of political power. He sees political power as the basic factor in comprehensive state power. This is very revealing for us today. If we take soft power as being made up of both cultural and political power, then we find that political power plays an enabling role as the basis for other elements of power to play a role. For instance, the United States’ military power, economic power, and cultural power grew during the period 2003 to 2006, but because the Iraq war launched by the Bush administration in 2003 lacked international legitimacy, U.S. capability in terms of political mobilization both at home and abroad—that is, political power—went into serious decline. Thus, the United States’ comprehensive national power shrank and its international status declined during those three years. This example, as well as that of the collapse of the Soviet Union, proves that political power is the operating power for resource power, military power, economic power, and cultural power. Without the former the latter cannot play their roles. On this basis, we can depict the relationships among the various factors of power as in figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6 Relationships among the various factors of power

If CP stands for comprehensive state power, M for military power, E for economic power, C for cultural power, and P for political power, then figure 2.6 may be rewritten according to the following formula:

CP = (M + E + C) × P

According to this formula, given no change in China’s current military, economic, or cultural power, it is only if China can greatly increase its political power—at least its strategic reliability—that China can greatly increase its comprehensive national power and international status. We may take the 2006 China-Africa Summit as an example. The total of China’s aid to African countries over the previous three years had not exceeded that of Europe or the United States, but the positive reaction to China’s aid from African countries vastly exceeded that to aid from Europe and the United States. The reason was not that the sum of aid offered by China was greater than that given by Europe or the United States, but rather that China’s aid to Africa has no political conditions attached, whereas European and American aid comes with political conditions. China’s sincerity in its economic aid has increased its political influence. What this tells us is that although the work of increasing China’s soft power includes both political and cultural power, the key lies in political power.

Strategy of Ascent

If the basis for China’s strategy of ascent is based on increasing political power, then the current versions of strategy popular in academia do not apply to China’s situation. The idea of economic construction as the core made materialism the dominant social belief in China. This had a strong influence on the discussion of the rise of a great state. Academia discusses four kinds of important strategies: the strategy of change (multipolar or confrontational), the strategy of avoidance (independent autonomy or isolationism), the strategy of merging (free rider or following the strongest), and the strategy of following the crowd (multilateral cooperation). Apart from the strategy of change, the other three strategies are all based on the logic of increasing China’s economic wealth.

Unlike the materialist strategy, the strategy Xunzi recommends for a rising power stresses human talent, that is, it focuses on competition for talent. Xunzi attributes changes in international politics to the political ideas of the leader and makes the choice and employment of talented persons the basic strategy for strengthening a state. In 1935, Joseph Stalin proposed the slogan “Cadres determine everything.” In 1938, Mao Zedong proposed a similar view that “once the political line is determined, the cadres are the decisive factor.”64 Their views are like Xunzi’s. At present, China’s strategy of seeking talent is still mainly used for developing enterprises and has not yet been applied to raising the nation as a whole. Talent is still understood as having to do with technicians rather than politicians or high-ranking officials. What Xunzi’s ideas about talent tell us is that the strategy of seeking talent should not be one of enterprise development. Rather, it has always been the strategy for the rise of a great power. The personnel requirements for the rise of a great power are not for technicians but for politicians and officials who have the ability to invent systems or regulations, because a pronounced ability to invent systems and regulations is the key to ensuring the rise of a great power.

If in the agricultural era of two thousand years ago the success or failure of the rise of a great state was determined by human talent, then, two thousand years later, the economic development of today’s knowledge economy is also determined by human talent; hence, we can suppose that the factor determining the success or failure of a rising power today is also human talent. Xunzi thinks that there are many talented people with both morality and ability, and the key is whether the ruler will choose them. This tells us that the strategy of finding talent to ensure the rise of a great power has several aspects. One is that the degree of openness is high: choosing officials from the whole world who meet the requisite standards of morality and ability, so as to improve the capability of the government to formulate correct policies. For example, in ancient times, the Tang Dynasty in China and the Umayyad Empire in North Africa, Spain, and the Middle East, in the course of their rise, employed a great number of foreigners as officials. It is said that at its peak more than 70 percent of officials in the Umayyad Empire were foreigners.65 The United States has attained its present hegemonic status also by its policy of attracting talented and outstanding foreigners. A second point is that the speed of correction was rapid. Unsuitable government officials could be speedily removed, reducing the probability of erroneous decisions. This applied to all politicians and officials if they lost their ability to make correct decisions for any reason, such as being corrupted by power, being out-of-date in knowledge, decaying in thought, suffering a decline in their ability to reflect, or experiencing deterioration in health. Establishing a system by which officials can be removed in a timely fashion provides opportunities for talented people and can reduce errors of policy and ultimately increase political power.

Equitable International Norms

After the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, equality of state sovereignty gradually developed to become a universal international norm. Xunzi’s thought is the exact opposite of equality of sovereignty. He thinks that norms for an unequal hierarchy are a help in preventing interstate conflict. Some countries are concerned that China’s rise will result in a return to the tribute system of East Asia. The tribute system once played a role in maintaining regional order but it is outdated for the modern world. In fact, any effort to restore the tribute system will weaken China’s capability for international political mobilization. Furthermore, the objective power status of large and small states is not equal. Establishing hierarchical norms is a help in maintaining a balance between a state’s power and its international responsibility and is a help in reducing international conflict and improving international cooperation

In current political discourse, hierarchy is a pejorative term, implying inequality. Objectively, however, not all states are alike in power, and therefore hierarchical norms are the only way to ensure equity. The norm of equality cannot maintain equity. Boxing competitions are carried out according to different grades of weight. This is one kind of hierarchical norm and it serves to guarantee the equity of the competition. To fail to distinguish grades of weight and to rely only on norms of equality to determine the winner would be to fail to uphold equity. According to Xunzi’s interpretation of the system of Five Services, distinctions in international norms should be decided according to a state’s status in international society. Large states with a central power status in the world should be subject to more stringent international norms, whereas marginalized states that lie farther away from the center of world power should be subject to more relaxed international norms. This is an unequal international norm that helps to uphold international equity. In the cooperation of the 10 + 1—the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China—China is required to implement the norm of zero tariffs in agricultural trade before the ASEAN states do. This unequal norm enabled the economic cooperation of the 10 + 1 to develop more rapidly than that between Japan and ASEAN. Japan’s demand for equal tariffs slowed the progress of its economic cooperation with the ASEAN states, which lags far behind that of China and ASEAN.

Historically, neither hierarchical norms nor norms for equality have been able to prevent large-scale international war from breaking out, but if we examine recent international history, we can see that in those areas that implemented hierarchical norms, international peace was better maintained than it was in areas that had norms for equality. During the Cold War, the equal status of the United States and the Soviet Union was such that they undertook many proxy wars in order to compete for hegemony, while their special status in NATO and in the Warsaw Pact, respectively, enabled them to prevent the members of these alliances from engaging in military conflict with one another. China’s rise cannot avoid influencing the international security system. Now, what kind of international norms should China propose to uphold international peace? To maintain world peace requires great capability, and none but a superpower has that kind of capability. Based on Xunzi’s understanding that hierarchical norms are beneficial in preventing conflict, China should propose that large states and small states should have different international responsibilities, and that different states should respect different security norms. For instance, in upholding international peace, small and large states with different security responsibilities have different rights. If nuclear weapons do not proliferate, then nuclear states must strictly adhere to nonproliferation while providing security guarantees to nonnuclear states.

I personally think that a phrase of Xunzi’s can summarize his interstate political philosophy: “Hence, in matters of state, norms being established, one can attain humane authority; reliability being established, one can attain hegemony; political scheming being established, the state will perish.”66 When applied to the strategy of China’s rise, this means that by making political power the foundation and constantly renovating the political system, China will rise to become the world’s leading power; if it develops political, military, and economic power on an equal footing, then it can become a great power. If it makes economic construction the core, then it will gradually become a medium-level developed country. If political strife is the guideline, then it will decline. Xunzi’s thought is but one of many schools of interstate political philosophy that were current in ancient China. If we can rediscover more interstate political ideas of ancient Chinese philosophers and use them to enrich contemporary international relations theory, this will provide the guideline for a strategy for China’s rise. There are also defects in Xunzi’s thought; hence, in borrowing ideas from him we need to exercise caution.