![]()

The Two Poles of Confucianism: A Comparison of the Interstate Political Philosophies of Mencius and Xunzi

Mencius and Xunzi were two great pre-Qin Confucians, yet generations of scholars gave them radically different assessments: Mencius was raised to the status of “Second Sage” after Confucius, while Xunzi remained neglected for centuries until the late Qing Dynasty (nineteenth century). The main reason for this was that Xunzi’s thought was close to that of the Legalists, and two of his disciples, Hanfeizi and Li Si, were prominent Legalist scholars and politicians. Hence, in a society dominated by Confucian orthodoxy, he was “discriminated” against.1

From the point of view of research in international political philosophy, however, Xunzi most certainly deserves to be highlighted. Xunzi lived at the end of the Warring States Period and died just seventeen years before the first emperor of Qin unified China in 221 BCE. Hence, he had the opportunity to personally experience, as well as understand on the basis of texts, practically the whole course of events and history of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (eighth to third century BCE) and on this basis propose his own point of view and his own ideas about international politics. Therefore, he may be seen as the great synthesizer of international political philosophy of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. In sorting out and studying his international political philosophy, we find that his academic importance is indisputable. If we take Xunzi as the endpoint of international political philosophy in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, then Mencius is a key point in the same era but earlier than Xunzi. As a student of Mencius’s international political philosophy, I have found that they have areas of agreement as well as areas where they sharply disagree. These similarities and differences show that both inherited the same academic lineage and also show how Xunzi criticized and developed the thought of his predecessor, Mencius. In this essay I make a simple synthesis and comparison of the similarities and differences in the hope that it will awaken the reader’s interest.

Put simply, what Mencius and Xunzi hold in common in their international political philosophy is their methodology. What they share to some extent is their understanding of international power, and where they differ is in their understanding of state power, the origin of conflict, and the way to resolve conflict. Naturally, the contributions that their international political philosophies make to contemporary international relations theory and China’s foreign policy are not identical.

AREAS OF AGREEMENT

In reflecting on the international questions they faced, Mencius and Xunzi adopted similar methods of analysis. They both set their level of analysis at that of the individual.

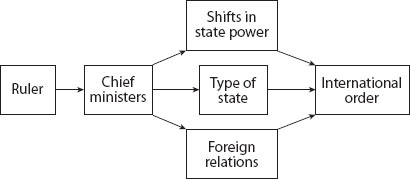

In Mencius’s view, the type of state determines the nature of the international system and international order. In his analysis, the nature of the international system as a dependent variable has two variants, namely, the system of humane authority and that of hegemony. The dependent variable of international order also has two variants, namely, order and disorder. The independent variable of the nature of the state has two variants, namely, the sage king and the hegemon. Mencius’s definition of humane authority is a state “that practices benevolence by virtue,” whereas his definition of a hegemonic state is “one that pretends to benevolence but uses force.”2 In Mencius’s language, the terms sage king and hegemon both refer to the nature of the state and also to the type of ruler, and can refer to the nature of the system as well. In other words, the type of ruler, the nature of the state, and the nature of the system are three ways of expressing the same thing. This is exactly the same as Xunzi’s analytical frame. The specific logical relationship is that the ruler who implements humane (or hegemonic) government may make the state become humane (or hegemonic) and then go on to establish a system of humane authority (or hegemony). A system of humane authority is peaceful and hence there is order, whereas a hegemonic system is unstable and hence there is disorder.

Like Xunzi, Mencius sets his analytical level not at that of the state but rather at that of the individual. In his analysis, the nature of the state is only a mediating variable. The basic cause that determines the nature of the state is the ruler. A given type of ruler leads to a given type of state. A ruler who implements humane authority will have a humane state, whereas a ruler who implements hegemony will have a hegemonic state. In this way, the ruler himself will ultimately shape and determine the features of the entire international system. Mencius and Xunzi had good reasons for doing their analyses at the individual level. A state is a political organization formed by human beings. In the linguistic system of contemporary international relations theory, idioms such as a state thinks or a state decides use the word state synecdochically. In fact, a state itself cannot think or decide. It has no way of acting. What can think, decide, and act are the people in the state, especially the ruler. Therefore, Mencius thinks that the ruler and the state are of the same nature. Often in his writings he refers to the ruler in place of the state, as for instance, “O King, if you should but implement benevolent governance for the people,” or “if the king goes to punish them, who will oppose the king?”3 or “if the ruler of the state likes benevolence, he will have no enemies in all under heaven.”4 In fact, it is not the ruler himself who has no enemies in all under heaven; it is rather the state, which the ruler who likes benevolence represents.

Xunzi is a conceptual determinist whereas Mencius is a conceptual determinist with a tendency toward dialectic. They both think that the persons of the ruler and the ministers are the original motivation for all state conduct. Mencius’s dialectical tendency lies in his denial that force has any importance to a state that aspires to humane authority. But he recognizes the important role of force to any state that aspires to hegemony. He says, “Using force and pretending to benevolence is the hegemon. The hegemon will certainly have a large state. Using virtue and practicing benevolence is the sage king. The sage king does not rely on having a large territory. Tang had seventy square kilometers and King Wen had a hundred square kilometers. Should you make people submit to force rather than to the heart, force will never suffice; should you make people submit to virtue, they will heartily rejoice and sincerely follow, as the seventy disciples followed Confucius.”5 This passage says that to become a hegemon a state must be large and powerful, whereas to become a humane authority a state relies not on military force but on the attractive force of morality, which causes other states readily and sincerely to submit and come to the king. Furthermore, Mencius even more than Xunzi points out clearly that it is enough to rely on the will of the ruler and the ministers. Their firm determination can effect a rapid change from hegemon to humane ruler or from humane ruler to hegemon. Mencius encourages King Xuan of Qi to implement royal government by saying, “Hence the ruler is not a humane ruler because he does not act as one, not because he cannot.”6

Mencius and Xunzi both adopt a strict method of analysis, that is, they use a single variable to explain the changes in the logical chain of cause and effect. Both take the idea of the ruler as the first independent variable and international order as the ultimate dependent variable and construct a progressive layered logic chain of cause and effect. Therefore, figure 5.1 applies equally to Xunzi’s and to Mencius’s international political thought.

Finally, Mencius and Xunzi both use the method of induction on the basis of isolated cases to present their point of view. In fact, this method of research is the one commonly adopted by scholars in the pre-Qin era. In assessing this method, Yan Xuetong points out in chapter 2 of this volume, “Many of the examples he [Xunzi] chooses come from historical legends. They lack any time for the events, background, or basic account and there is no way of ascertaining their authenticity. Moreover, his examples lack the necessary variable control” and their “scientific value is poor.” The veracity and plausibility of the cases are not very strong. Hence, “according to the standard of modern science his analytical method is not scientific.” As a scholar educated in contemporary social sciences, I completely agree.

Figure 5.1 The chain of causation between the ruler and international order

If you are a scholar with a sense of history, however, then you will find Professor Yan’s remarks quoted here a bit hard on the ancients. Most of the pre-Qin classics were lost in the confusion at the changeover between the Qin and Han dynasties. The works of the masters that we now see have passed through the large-scale compilation and reading of the Han Confucians. Hence, historical material that nowadays seems to be lacking in “real origins” may not necessarily have been inauthentic history at the time of the masters, or they may have generally held that these examples were real history. Their veracity is a bit like that of contemporary people who believe that the earth orbits the sun. This fact does not require us to state the time, background, process, and origins of this belief.

POINTS OF PARTIAL SIMILARITY

Mencius’s and Xunzi’s views of international power or world leadership have points in common and points where they differ. Neither pays attention to the structure of international power or relations between large states. Rather, they are interested in the nature of international power. The difference lies in that Mencius specifically points out the direction and policy by which a state can attain humane authority, whereas Xunzi does not specially note this. Furthermore, Mencius forcefully rejects hegemony, whereas Xunzi is not opposed to a state making efforts to attain hegemony.

Xunzi separates international power into three kinds—humane authority, hegemony, and tyranny—whereas Mencius recognizes only two kinds: humane authority and hegemony. Both think that humane authority is the highest form of power in the world. Its foundation is the morality of the ruler (the Son of Heaven). To possess humane authority is almost like possessing world leadership, or “possessing all under heaven.” Mencius says, “Should you exercise humane government, then all within the four seas would lift their heads and gaze on you and seek to have you as their prince.”7 “Possessing all under heaven” refers not to using military force to conquer the world but rather to gaining such political legitimacy that the various states of the world consciously submit to one’s leadership. Both scholars think that one does not acquire world leadership by seizing it, but rather it spontaneously belongs to one.8 The conversation between Mencius and his pupil Wan Zhang over the abdication of Yao in favor of Shun illustrates this point:

Wan Zhang said, “Yao gave all under heaven to Shun. Is that not so?”

Mencius replied, “No. The Son of Heaven cannot give all under heaven to anyone.”

“So who gave all under heaven to Shun?”

He replied, “Heaven gave it to him.”9

The problem is that heaven cannot speak, so how do we know that a particular person or state has received the mandate of heaven? Mencius points out one can observe the direction of a person’s mind. If the mind is directed positively, this is a sign that one has obtained the mandate of heaven, and from this one can possess world leadership. If a person’s mind is directed negatively, then this means that one has lost the mandate of heaven, and from this one will lose world leadership. He says, “He appointed him to preside at the sacrifice, the hundred spirits enjoyed his offerings. This showed that heaven accepted him. He appointed him to be in charge of affairs and the affairs were well managed, so that the common people were at peace with them. This showed the people accepted him.”10 He again uses the example of Yao abdicating in favor of Shun to prove his point: “Of old, Yao presented Shun to heaven and heaven accepted him. He revealed him to the people and the people accepted him. Therefore I say, ‘Heaven does not speak, it simply shows itself by deeds and actions.’”11

Although Xunzi argues that a state should make an effort to attain humane authority, he does not say what policies the enlightened ruler or state should adopt to this end, whereas Mencius does give a more detailed prescription. Mencius’s basic suggestion is that the ruler should first raise his moral standing to become a benevolent prince and then both at home and abroad he should “implement benevolence.” Mencius begins from the premise that human nature is good, holding that “all people can become a Yao or a Shun,” the ruler naturally being no exception. Yao, Shun, Yü, Tang, and Wu were all ancient sage kings and the models for later rulers. From their way of behaving to their actions, they embodied the Confucian political philosophy of being “sages within and humane rulers on the outside.” Hence rulers should study and imitate their every word and action. Mencius says, “If you dress in the dress of Yao, recite the words of Yao, and do the deeds of Yao, then you are quite simply Yao.”12 That is, by studying and imitating the sage kings the ruler becomes a sage king himself.

If the ruler has an idea of benevolence and justice, the next step is to implement benevolent government.13 “Benevolent government” is a policy for both domestic and foreign affairs. In domestic matters, Mencius asks the state to restrict its excessive absorption of social resources, adopt a policy of light taxation, and ensure that the basic requirements of life are guaranteed for the common people. Once the ordinary people’s basic livelihood is guaranteed, then you must promote education, lest “well-fed, adequately clad, and peacefully housed, but without education, they are close to the birds and beasts.”14 Regarding the state, education of the people serves to establish a harmonious society. Mencius thinks that teaching the people is geared toward making the ordinary people “understand human relationships,” such that “there is affection between parents and children, justice between rulers and ministers, distinct roles for husband and wife, sequential order between older and younger siblings, and trustworthiness among friends.”15 Once these five areas are performed well, society will naturally be harmonious and ordered.

In his foreign policy, Mencius also stresses benevolence and justice as the main principle. He opposes the then-common practice of states employing hegemonic strategies to go to war, annexing land and increasing their populations. He especially emphasizes that the government should stop using war to annex land and people. He says, “Enacting one unjust deed, killing one innocent person, and obtaining all under heaven: they [sage kings] all would not have done such things.”16 Again, “To take from one state to give to another is something a benevolent person would not do. How much less can one do so by killing people?”17

On hegemony Xunzi and Mencius part company. Xunzi thinks that humane authority is the ideal form of power and hence deserves being promoted, whereas tyranny is the worst form of power and hence should be opposed. He has no moral reaction to hegemony nor is he opposed to its existence. On the contrary, he implicitly supposes that a hegemonic state must have a considerable degree of morality even if its morality falls far short of that of a humane authority. He says,

Although virtue may not be up to the mark or norms fully realized, yet when the principle of all under heaven is somewhat gathered together, punishments and rewards are already trusted by all under heaven, all below the ministers know what they can expect. Once administrative commands are made plain, even if one sees one’s chance for gain defeated, yet there is no cheating the people; contracts are already sealed, even if one sees one’s chance for gain defeated, yet there is no cheating one’s partners. If it is so, then the troops will be strong and the town will be firm and enemy states will tremble in fear. Once it is clear the state stands united, your allies will trust you. Even if you have a remote border state, your reputation will cause all under heaven to quiver. Such were the Five Lords. Hence Huan of Qi, Wen of Jin, Zhuang of Chu, Helü of Wu, and Goujian of Yue all had states that were on the margins, yet they overawed all under heaven and their strength overpowered the central states. There was no other reason for this but that they had strategic reliability. This is to attain hegemony by establishing strategic reliability.18

This passage means that even if the morality of a hegemonic state is not perfect, it understands the basic moral norms of this world. The domestic and international policy of a hegemonic state must take as its principle reliability in its strategies. Domestically it should not cheat the people and externally it should not cheat its allies.

Mencius also thinks that humane authority is the ideal form of international power and most worth aspiring to, but he is vehemently opposed to hegemony. He thinks that even if a hegemonic state succeeds in dominating the whole world, its span will be brief and illegitimate and it will not win the support of many countries because a hegemonic state “uses force to subdue people.” The biggest problem with using force to subdue people is that the states that follow one “will not follow from their hearts, but because their strength is insufficient,” and therefore they will look for an opportunity to rebel.19 Moreover, although hegemons’ false benevolence, fake justice, and paucity of goodness may allow them to cheat people for a while, it cannot be forever. The result of their lack of benevolence will become apparent and as a consequence they will lose the minds of the people and end up losing hegemony. Mencius goes on to say that a state that seeks hegemony for itself risks its own security, because that type of state must practice hegemonic government and this requires seeking profit in everything, and seeking profit in everything will upset the orthodox order of society. He says, “If ministers serve their prince with an eye to profit and sons serve their fathers with an eye to profit and younger brothers serve their older brothers with an eye to profit, so you end up expelling benevolence and justice between rulers and ministers, fathers and sons, and older and younger brothers and all draw close to one another with an eye to profit, such a society has never avoided collapse.”20 Furthermore, promoting hegemonic government will make all large states your enemies and they will fight with your allies. This requires an expenditure of state force and is a threat to the life and property of the people. Mencius uses the example of King Hui of Liang pursuing profit alone with the result that the power of his state went into decline to explain that profit is a danger to the state and the ordinary people. He says, “For the sake of territory, King Hui of Liang trampled his people to pulp and took them to war. He suffered a great defeat but returned again only fearful that he would not win so he urged on the son whom he loved and buried him along with the dead. This is what is called ‘starting with what one does not love and going on to what one does love.’”21 Thus, he concludes, “The three dynasties acquired all under heaven by benevolence and they lost it through lack of benevolence. This is the reason why states decline or flourish, rise or fall. If the Son of Heaven is not benevolent, he cannot retain what is within the four seas. If the feudal lords are not benevolent they cannot retain the altars of soil and grain.”22

From Xunzi’s and Mencius’s analyses of hegemony set out earlier, we can see that the origin of the difference between their views on this question lies in a difference in their definitions of hegemony. Xunzi thinks that the basis of hegemony is hard power and reliability in strategy,23 whereas Mencius thinks that the only basis for hegemony is hard power. Therefore, Xunzi accepts that the existence of hegemony has certain positive features, whereas Mencius thoroughly rejects it. What is interesting is that Xunzi’s analysis of hegemony is much closer to the United States’ advocacy of hegemony, namely, that a superpower must not only exercise hegemony but also be faithful in its alliances. When its allies are threatened it should not spare itself in protecting them, as in the 1960s and 1970s the United States protected South Vietnam and took part in the Vietnam War. Thus, we also find that the domino theory and Xunzi’s theory of reliability in strategy have points in common. Mencius’s attitude to hegemony, by contrast, is very much like that of the Chinese government. Since 1949, the various Chinese governments have firmly opposed hegemony and hegemonism.24

POINTS OF DIFFERENCE

Understanding of State Power

Although Mencius and Xunzi both emphasize the importance of political power and acknowledge it as the primary factor in state power, they have different opinions about the degree of importance of political power.25 Mencius greatly respects political power and depreciates the importance of economic and military power, whereas Xunzi thinks that all three are necessary, but political power is the foundation for the exercise of economic and military power.26

Professor Yan says, however, that “Xunzi overlooks the importance of hard power for humane authority.” I beg to disagree. Professor Yan says,

Even if the territories of Bo and Hao ruled by the kings Tang and Wu, respectively, were small, the states of the feudal lords of that time may have been even smaller and weaker. By the Spring and Autumn Period, the scale of states had generally increased in size. Both Qi and Qin were once larger than Chu, and so Chu was not the strongest state at the time. Therefore, when Xunzi uses the example of Chu’s being larger than the lands of the kings Tang and Wu and yet not being able to attain all under heaven to prove that power is not important for humane authority, his argument is less persuasive.

I think that here Professor Yan has misread Xunzi and misread history. Although it is certain that the territories of Kings Tang and Wu were larger than those of some of the feudal lords, their territories were far smaller than those ruled by King Jie of the Xia and King Zhòu of the Shang; hence, in terms of hard power they were definitely on the weaker side. For example, when King Wu led a punitive expedition against King Zhòu, he certainly had fewer troops than King Zhòu did.27 So when Xunzi says that the kings Tang and Wu were able to attain humane authority even with territories of only one hundred square kilometers, he is speaking of their hard power in relation to that of King Jie of the Xia and King Zhòu of the Shang. Furthermore, in land area, for most of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods the state of Chu was the first or second largest state. It was only toward the end of the Warring States Period that it was overtaken in size by Qin. Moreover, in the Spring and Autumn Period, Chu was certainly what could be called a superpower. It contended for hegemony first with Qi and then with Jin and was very rarely eclipsed. Hence, I think that there is a certain plausibility in Xunzi’s using the failure of a state as large as Chu to attain all under heaven and comparing this with the territories of Kings Tang and Wu as proof that hard power is not important to humane authority.

The difference in view of Mencius and Xunzi on the issue of state power may be owing to a difference in political philosophy. Mencius is a pure ethical idealist who believes that for the state to simply seek material goods, especially to raise its military power, is harmful. He uses the example of King Hui of Liang, who set his sights purely on profit, as quoted earlier. In contrast, a state that seeks benevolence and justice can attain humane authority over all under heaven and will have no enemies at all.

Mencius argues,

With a territory of a hundred square kilometers, it is possible to be king. O King, if you should implement benevolent governance for the people, reduce punishments, lighten taxes and duties, allowing for deeper plowing and ensuring that weeding is well done, then the fit will spend their holidays practicing filial piety, brotherly affection, loyalty, and constancy. At home they will serve their parents and elders; outside they will serve their masters; then they can but take wooden staves in hand and attack the armored troops of Qin [in the northwest] and Chu [in the south], whose rulers steal their people’s time so that they are not able to plow or hoe to support their parents. Their parents freeze and starve; their brothers, wives, and children are dispersed. They set pitfalls for their people or drown them. If the king goes to punish them, who will oppose the king? Thus it is said, “The benevolent has no enemies.”28

This is to say that a state that speaks of benevolence and justice and implements benevolent government will be united internally. Political motivation will be strong. In contrast, a state that speaks of gain and implements hegemonic government will be rent apart internally and its political motivation will be weak. In a conflict between a king and a hegemon, the king can win without a fight.

For Mencius the pursuit of political morality is called “justice” and the pursuit of military and economic power is called “profit.” The relationship between Xunzi’s three factors of state power—political power, economic power, and military power—thus becomes in Mencius’s thought one between justice and profit. Hence, the debate about justice and profit becomes a debate between the king and the hegemon. In other words, if the ruler speaks of justice, proposes the kingly way, and implements benevolent government, then the result will be that political power will rise and ultimately one will become king of all under heaven. If the ruler speaks of profit, proposes the hegemonic way, and implements hegemonic government, although some countries may be called hegemonic, most will descend into political chaos and a diminution of state power. Moreover, even the successful hegemonies will be unable to hold on to their status for long. Their state power will rapidly decrease and they will lose their hegemonic status. The deductive relationships in Mencius’s debate between justice and profit can be set out as in figure 5.2

Figure 5.2 Logical relationships: justice vs. profit and humane authority vs. hegemony

The Origin of Conflict

Xunzi believes that human nature is evil and Mencius believes that it is good. Their viewpoints are diametrically opposed, and this leads them to equally opposed views about the origin of conflict. Xunzi thinks that there is no end to desires and that material goods cannot satisfy them. Since desires cannot be satisfied, people will go on seeking more. This quest will never end and hence it will give rise to competition, which will continue and break out in violent conflict. He says, “When man is born he has desires. Though desires are unfulfilled, yet he cannot but seek. If he seeks, and has no limits set, then he cannot but conflict with others. If he conflicts with others there will be disorder, and if there is disorder there will be poverty.”29

It is relatively easy for an exponent of the evil of human nature to start from human desires and postulate the origin of violent conflict, but how an exponent of the goodness of human nature can postulate the origin of violent conflict requires a lot more effort to explain. The question confronting an exponent of the goodness of human nature such as Mencius is: if human nature is good, where does the evil present in real life come from? If a person could but maintain the goodness of their nature, then international conflict would not take place.

First, Mencius thinks, not that human nature is originally good, but that human beings have a natural inclination toward the good, that is, that they have an a priori basis for being good. These naturally good tendencies need to be directed, educated, and fostered before they can be fully expressed—that is, nature may move toward goodness and hence the goodness of human nature is a process. Mencius says, “It is no surprise the king is not wise. Although there are plants in the world that grow easily, yet with one day of sunshine and ten days of frost, they will not be able to grow. I see you very rarely, and the moment I leave the Jack Frosts come. I may bring out some buds, but to what good?”30 That is, even though the king has the seeds of goodness in his heart, yet they cannot grow properly with one day of violence or ten of cold. This is especially so when Mencius leaves, since the people who lead the king to fall into injustice (the frost) will gather around him and egg him on to do wrong. Therefore, Mencius’s theory of the goodness of human nature says, not that human nature is originally good, but that the heart has seeds of goodness, which may be developed to do good.31

Second, the fact that Mencius thinks the king can be led astray by small-minded persons shows that he acknowledges that people may be led astray by profit and desire. Mencius distinguishes two kinds of organ in the human body. The first is the “small” organs, such as the mouth, the ears, the eyes, and the nose. These organs are designed to satisfy natural desires: “The mouth is oriented to taste, the eye to colors, the ear to sounds, the nose to smells, the four limbs to ease and rest. This is nature. There is also about them what is of Heaven’s decree, so the gentleman does not ascribe everything to nature.”32 The second kind is the “great” organ, the good mind, the mind of benevolence, justice, rites, and wisdom. There is a contradiction between the great and small organs: namely, the tension between benevolence and profit or between good and evil. A person becomes the sort of person he is by following the effects of the organs; that is, “those who follow the great organ are great people; those who follow the small organs are petty people.”33

Now, why is it that some people follow the great organ (become exemplary persons) and some the small organs (become petty people)? Mencius says, “The organs of ears and eyes do not think but are veiled by things. When one thing encounters another thing, then it leads it astray. The organ of the mind does, however, think. By thinking it obtains; by failing to think it fails to obtain. These are what Heaven has given to us. Establish yourself in that which is great and then what is small cannot steal from you. This alone is what makes a great person.”34 In other words, if a person does not restrain the organs of desire, such as ears and eyes, then he will be led astray by profit. If he can use his mind to think, then he can maintain his good nature. Hence, whether one becomes an exemplary or a petty person depends on one’s own choice.

Ways to Resolve International Conflict

Xunzi thinks that increasing the material goods and wealth of a society will not resolve the conflict that may arise between people, because human desires will increase along with the increases in wealth and will continue to rise. He advocates using the rationality of the mind to control desires, and he believes that the way to strengthen the rationality of the human mind is to establish social norms (rites).35 Norms can make human desires reasonable and can also increase the capacity for satisfaction. When desires decrease and the capacity for satisfaction increases, then the two will easily come into balance. Moreover, norms can also distinguish social classes, so people will act according to the norms proper to their class and thus avoid conflict arising. Xunzi’s reliance on external forces to suppress conflict is at one with his philosophical theory of the evil of human nature.36

I am in full agreement with what Yan Xuetong says about the role hierarchical norms can play in suppressing domestic and international conflict, but it would seem that he has overlooked one issue: given that norms are implemented and maintained by people (or by states), then how can they be implemented or maintained when there are evil persons (or evil states) that seek their own ends by flouting norms, especially when these people (or states) have considerable force?37 Although it may be possible to wait in expectation of a true kingly state, such states occur only rarely in history, and when there are none how is one to cope? I fear that one must place one’s hope in the collective response of persons or states with a sense of justice. Then force is simply the support for implementing and maintaining norms.

Mencius’s resolution of international conflict is quite different from Xunzi’s. Since he advocates the goodness of human nature, Mencius believes that the idea of goodness in the human mind will ultimately overcome evil desires. Of course, Mencius believes in the effectiveness of “rites” in suppressing conflict between people, but he is faced with a world in which “rites are dethroned and music is bad.” Therefore, the first thing to be done is to restore the ritual order. Hence he proposes a two-step strategy. The first step is to use persuasion and education to influence the rulers so that the goodness in their minds will suppress the evil. As for who can carry out this task, Mencius believes that it is worthy people like himself. Therefore, Mencius spent his life going from state to state (he visited Zou, Lu, Qi, Wei, and Teng). On his arrival he would first preach to the rulers the way of benevolence and justice with the aim of transforming them from their tendency to “talk of profit rather than talk of justice.” Through education, he would form and enlighten the goodness of their minds so that the inherent nature of benevolence, justice, rites, and wisdom would shine out and so that benevolent government would lay a foundation for thought.38

Once the ruler’s way of thinking has been rectified, the second step is to correct distorted human relationships, that is, to restore the ritual order.39 Mencius thinks that when the good in human nature is obscured by desire, human nature itself is distorted. When human nature is distorted, the relationships among people are also distorted. When human relationships are distorted, conflict will invariably arise. Therefore, to prevent violent conflict it is necessary to respect human relationships. The distortion of human relationships is shown in the demise of rituals among people. In human relationships there are hierarchical relationships (ruler and minister, father and son) and relationships of equality (between brothers, spouses, and friends). They can all be unified through the principle of benevolence and justice. He says, “Ministers will serve their lords with benevolence and justice; sons will serve their fathers with benevolence and justice; younger brothers will serve their elder brothers with benevolence and justice; so that ruler and minister, father and son, elder and younger brother will expel thoughts of profit and harbor benevolence and justice and draw close together.”40 With human relationships in order and the ritual order restored, and once the ruler has adopted the way of benevolence and justice, then a state will no longer harbor thoughts of gain against another. The more there are of this kind of kingdom then naturally the less there will be of international conflict.

Mencius’s plan for regulating international relations is for “internal inspection” or “internal reflection.” That is, he asks the individual to look into the goodness in his own mind and, by developing this goodness, to ease conflict, including international conflict. Now, Mencius is a Confucian like Xunzi but whereas Xunzi advocates a restoration of the Western Zhou system of Five Services, Mencius does not stress this. The reasons for this are twofold: first, the previously mentioned difference in their views regarding the goodness or evil of human nature, and second, a change in the times.

Xunzi lived at the end of the Warring States Period. By that time, Qin had already become the undisputed hegemon and had the power to unify China. Hence, the key political question then was in what way Qin would unify all under heaven. The previous unified world (all under heaven) had been the feudal system of the Western Zhou. Since this system had been idealized by Confucius and other Confucians as the system of Five Services, and its creation ascribed to King Wu of the Zhou and the duke of Zhou, Xunzi was bound to uphold this form of unified world.

Mencius lived in the mid–Warring States era. This was a time when the various states were in chaos and no one state could come to the fore and emerge as a hegemon, as Qin would later do. Mencius also hoped for unity in all under heaven and for a return to the feudal system of the Western Zhou, but given the conditions of international politics in his time it was very difficult to realize this hope. Hence although Mencius himself was confident about this goal, he had to realize that his duty at the time was to make people wake up and stop chaotic war. This can be seen in his dialogue with King Hui of Liang:

Suddenly he asked me, “How can all under heaven be calmed?”

I replied, “It can be calmed by being united.”

“Who can unite it?”

I replied, “One who does not like killing others can unite it.”

“Who can give it to him?”

I replied, “There is nobody in all under heaven who will not give it to him.”41

This exchange shows that Mencius was very busy trying to put the idea of benevolence and justice into the ruler’s mind and trying hard to form one ruler or several who could stop international wars. It was not yet the time for establishing international norms, since if peoples’ minds were not first correct, then even if there were norms in place no one would want to implement them with any sincerity.

THE MESSAGE OF MENCIUS’S INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY FOR TODAY

Mencius was a scholar of an idealistic moral bent and was used to converting political issues into moral ones. This meant that his political opinions could not become the first political strategic option of any state during his lifetime, when the strong devoured the weak. Xunzi was more realistic than Mencius. In his international political philosophy there is much that can be put into practice. Over time, however, the world of today has come to be unlike the jungle of the Warring States Period. The influence of morality and values cannot be discounted in international relations or in a state’s foreign policy. Hence, Mencius’s international political philosophy with its moral idealism still has something to contribute to the realization of China’s foreign policy and to international relations theory.

Mencius praises humane authority and denigrates hegemony. He thinks that the way to unite all under heaven is by conversion of hearts rather than by force. Even if historically no humane authority has been established that has been able to leave violence behind, Mencius’s viewpoint, which does not accord with history, gives us room for reflecting on what sort of great state China will develop into. If in the future China develops into a hegemonic state, then it will be a case of the rise and fall of yet another hegemon. If in the course of its rise, China can develop into a humane authority, then this will be a unique case in history of the rise of a great state. Although in recent years the Chinese government has proposed the political guidelines of “scientific development” and “taking the human being as the basis” (so its policy does have something in common with Mencius’s benevolent government), in its foreign policy China lacks a universal moral ideal or high point. The lack of this moral ideal means that many countries view China’s rise as that of a state thirsty for power and thus misread it as a serious threat to the stability of the international system. That is to say, China still lacks what can attract the countries of the world to naturally follow it.

Mencius stresses that a humane authority should first be a model political state in the international system. Hence, if China wants become a humane authority, it should establish itself as a model polity for the world. Only in this way will it be possible to attract other states to imitate it. Mencius thinks that the attractive power of a humane authority lies not in riches but in political ideals and in the model of social development founded on these ideals. Even though Mencius’s own view of benevolence and justice may not be adopted by the Chinese government in all its details, Mencius’s thought can still tell us that today, when China’s GDP has already attained a considerably high standard, the Chinese government should be all the more concerned about what kind of political ideal and model of social development should be created. This is not only to build a firm foundation for China’s own rapid progress but, even more, to exert sufficient international attraction to transcend the political ideals and social system of the West.

Mencius’s opposition to hegemony can still serve as a reference point for the Chinese government today. In fact, the hegemony that Mencius talks about is much more about the policy of strong states and not really a reference to the status of a state in the structure of international power. Hence, while China is rising daily, the Chinese government must, on the one hand, continue to affirm its principle of opposition to hegemony while, on the other hand, being very prudent and careful and doing everything to avoid other states’ thinking that it is pursuing hegemony. This requires China to stress area cooperation and multilateralism, and to uphold the authority of the United Nations and international legal norms.

Mencius’s international political philosophy may be summed up in one word as “the benevolent has no enemies.”42 Enemies here refers not only to military enemies but also to political enemies. The greatest lesson China can draw from this is that its development should be a process not only of increasing its power but also of expanding its political ideas and model. If power alone is exalted, this will lead people to be afraid and it will not win their admiration. On the contrary, if, when power is elevated, there is creativity in the area of ideas and models, then once China has risen it will become a humane state and that kind of state will win people’s admiration and respect.