![]()

A Comparative Study of Pre-Qin Interstate Political Philosophy

There were several schools of thought on interstate politics among thinkers of pre-Qin (pre-221 BCE) China. Understanding the differences and commonalities among these schools may help us glean from their thought ideas to enrich contemporary theories of international relations. Given the great complexity of pre-Qin political philosophy—both in the number of schools and in their teachings—it is impossible to cover everything. Hence, this essay is limited to the works of seven thinkers: Guanzi, Laozi, Confucius, Mencius, Mozi, Xunzi, and Hanfeizi. It relies on the fruits of established research and examines these seven thinkers from four different angles: ways of thinking, views on interstate order, views on interstate leadership, and views on transfer of hegemonic power.1 The nine concrete issues addressed are analytical method, philosophical concepts, cause of war, path to peace, role of morality, the nature of all under heaven, the basis for the right to leadership among states, unbalanced development, and transfer of hegemonic power. Finally, this essay will apply what has been learned from this study of Chinese thought to enrich contemporary international relations theory and present some findings relevant to China’s foreign policy.

CURRENT RESEARCH: ITS FINDINGS AND LIMITATIONS

Early on, scholars noted the richness of pre-Qin ideas on interstate politics and did some research in this field. For instance, in 1922 Liang Qichao published a History of Pre-Qin Political Thought.2 Two chapters of that book, titled “Unification” and “Antimilitarism,” presented the views of Laozi, Mencius, and Mozi regarding world government and war. Liang Qichao interpreted the pre-Qin philosophers’ idea of “all under heaven” as referring to the whole body of humankind. He saw this as a kind of universalism and illustrated it with Mencius’s saying, “How can all under heaven be settled? It can be settled by being united,” and Mozi’s “Only the Son of Heaven can unify the standards in all under heaven.”3 The book also quotes Laozi’s “Weapons are inauspicious instruments,” and Mencius’s “In the Spring and Autumn Period there were no just wars,” and Mozi’s chapter “Against Aggression” to prove that all three were pacifists, while holding that the Legalists were militarists.4 Although scholars had begun to work on bringing together the interstate political thought of pre-Qin philosophers, in these studies domestic politics and foreign affairs were not clearly distinguished and there was very little in the way of systematic work, and thus this work had little impact on contemporary international relations theory.

There are four ways in which research in pre-Qin political thought has advanced. The first is the fruit of study of ancient Chinese history. While the emphasis here is placed on the pre-Qin period as such and on specific events, there are some studies analyzing pre-Qin thought though very few are undertaken from the point of view of interstate politics. For instance, a history book by Yang Kuan devotes twelve pages to summarizing Daoist thought but of this only some hundred words are devoted to interstate politics.5 History books generally quote pre-Qin works to illustrate the political views of the philosophers but do not discuss the philosophies behind these views. For instance, by quoting Laozi’s sayings that “It is better for the large to keep low” and “the ocean becomes the king of all the rivers because it is low-lying,” a scholar argued that Laozi opposes the annexation of large states by small ones. But this kind of analysis cannot explain the logic of Laozi’s thinking that a large state’s ceding power can head off the outbreak of war.6 If we look at this from the perspective of international relations theory, we will discover that the logical cause of Laozi’s thinking is that he believed war originated from human desires and for a large state to cede power to others indicated that it had no desire to swallow up other states. When a large state has no desire to annex other states and small states have no power to do so, then wars of annexation can be avoided.

The second kind of study is that devoted to the history of Chinese thought. Here the emphasis is placed on analysis of the various schools: Confucian, Daoist, Mohist, and Legalist. There are also studies devoted to specific thinkers.7 Books of this type enable us to understand the evolution of pre-Qin thought and the specific thought of the various pre-Qin masters. For example, scholars have discovered that “before Mencius, there was no clear opposition between ‘king’ and ‘hegemon’; there was only a political difference.”8 A summary like this permits us to conclude that there were different kinds of hegemonic power and helps in improving contemporary hegemonic theory. This kind of research is undertaken from the point of view of domestic politics, however, and does not look at the thought of pre-Qin thinkers from the angle of interstate politics. For instance, Guanzi’s theories on ruling the world in Conversations of the Hegemon have been summarized as discussing “rulers, power, and the relation between rulers and ministers” and understanding that “hegemons and sage kings have a sense of the right time. Having perfected their own states while neighboring states are without the Way is a major asset for becoming a hegemon or sage king.” This illustrates the idea that there is a right time to exert hegemony.9 If one looks at this statement from the point of view of international relations, it does not merely say that exertion of hegemony requires the proper time; more important, it points out the law of relative strength of a rising power to other states. In other words, whether a large state should exert itself to attain hegemonic status is determined by the relative proportion of strength between that state and others, not by an increase of its own absolute strength.

The third kind of study is dedicated to the history of China’s foreign relations. This approach views the thought of the pre-Qin masters from the perspective of diplomatic relations, and holds that it is already evidence of “interstate political theory.”10 This kind of research has changed the idea that the relations of the feudal states were not interstate relations and, hence, has opened a new perspective for understanding the thought of the pre-Qin masters from the point of view of interstate politics. Scholars adopting this approach use ideas from contemporary international relations theory to expound pre-Qin diplomatic thought and thus have opened up a new way of understanding these thinkers. For example, they use “idealism” and “realism” to differentiate the pre-Qin thinkers, taking Laozi, Mozi, and Confucius as “idealists” and Guanzi and Yanzi as “realists.”11 We must be very careful in applying concepts of contemporary international relations theory to the thought of the pre-Qin masters, however, because although there are instances in which these concepts and those of pre-Qin thought overlap, there are also differences. Hence, this kind of ticking off from a list may give rise to misunderstandings. Thus, in contemporary international relations theory, idealism refers to the idea of being founded on the notion of world government and hence avoiding war. This theory is compatible with that of Confucius—whereby the Zhou Son of Heaven is held in respect and the rites of Zhou are used to restrain war between the feudal lords—but it is not compatible with Mozi’s rejection of all war nor with Laozi’s opposition to the use of Zhou rites to uphold peace. Mozi’s thought is closer to modern pacifism, whereas Laozi’s is closer to anarchism.

The fourth kind of research is in international relations. This kind of research took off only in the twenty-first century. It employs ideas from contemporary international relations theory and undertakes comparative research into the political thought of the states of the pre-Qin masters. The initial results have focused on similarities between the pre-Qin masters and contemporary international relations theory. Some scholars maintain that as regards content there are many similarities between Western diplomatic thought and that of the pre-Qin masters. The West has moved from Grotius’s international legal idealism to realism; China went from Guanzi’s hegemonic order and Confucius’s moral order to the realism of Hanfeizi. Wen Zhong’s unlimited diplomacy and Machiavelli’s theories are the same.12 This work has provided us with a comparison of China and the West and has led us to recognize the richness of political thought among the feudal states of the pre-Qin masters.13 Nonetheless, some features of this work of comparison can be challenged. For instance, to describe the conference of the various peoples in the Zhou era as like the United Nations, or to treat the feudal states as independent nation-states easily leads us to overlook the differences between the two.14 At present the academic world accepts that the biggest difference between the nation-state and any other previous form of state is that the latter did not depend on international recognition. Previously, international recognition was not a prerequisite for acceptance as a state.

The results of international relations research have begun to head in a very revealing direction in recent years. Scholars are using pre-Qin thought and contemporary international relations theory to lead them to look for a way to shed new light on contemporary international relations theory. For instance, scholars have noticed that Hanfeizi adopts the view that the political system is an independent variable of the increase in a state’s power, enabling us to realize that there is a need to deepen our understanding of the relationship of between the system and both hard and soft power.15 Some scholars have studied the idea of intervention in Zuo’s Commentary and found that successful intervention depends on the degree of intervention and the consistency of purpose, not on the amount of power exerted.16 A Korean scholar has studied the Record of Rites and discovered that the idea of being a sage within and reigning without can help contemporary political leaders to undertake personal moral improvement and thereby enhance the international environment.17 Some scholars have noted that the Guanzi emphasizes a combination of the development of power in economics, military affairs, and politics, which can be of value to researchers interested in the strategy of rising powers.18 Having read the extracts in Zhongguo Xian Qin Guojiajian Zhengzhi Sixiang Xuandu (Readings in pre-Qin Chinese diplomatic thought), some scholars have remarked that the differences between the thought of the pre-Qin masters and contemporary international relations theory are more important than the similarities, because similarities simply reinforce each other whereas differences allow for the recognition of changes.19 Although the revelatory nature of this kind of research is powerful, little has been accomplished so far in comparing the interstate political thought of the pre-Qin masters.

In fact, none of these four kinds of comparative research of the interstate political thought of the pre-Qin masters has produced much. The main purpose of undertaking a comparison is to be able to grasp the true picture of pre-Qin thought so as to make new discoveries in theory, not to assess the past. That is what this essay attempts to do.

Analytical Levels and Epistemological Ideas

ANALYSIS OF THOUGHT

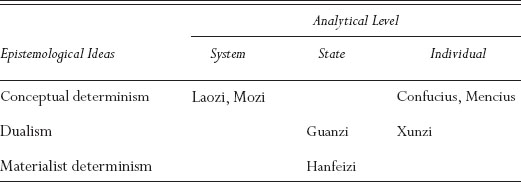

The language and vocabulary of the pre-Qin thinkers were very different from those used today, yet their way of thinking about problems and their logic were very similar. In their works there is no clear methodology, their patterns of thought are heterogeneous, and their analytical logic is contradictory in places. Hence, to clarify and understand the logic of their thought, this essay relies on their basic concepts and categorizes them according to modern epistemological methods. The two axes are those of analytical level and epistemological ideas. In this way we can group the seven authors (Guanzi, Laozi, Confucius, Mencius, Xunzi, Mozi, and Hanfeizi) according to table 1.1.

Levels of System, State, and the Individual

Following the three levels of analysis of international relations, we can classify the analytical perspectives of Mozi and Laozi as on the level of the system, those of Guanzi and Hanfeizi as on the level of the state, and those of Confucius, Mencius, and Xunzi as on the level of the individual person.

Mozi and Laozi analyze interstate relations from the viewpoint of the whole interest of the whole world rather than from that of the advantage of each state. Mozi believes that using war to attain preeminence is beneficial only to a few states, not to most. War enables a very few states to become hegemons but at the cost of many, many small states that perish. Hence, he concludes that war is the greatest abuse. In refuting the idea that states should become strong and exert hegemony he says, “In the past the Son of Heaven enfeoffed the princes, more than ten thousand of them; today, because they have been annexed, the myriad and more states have been eliminated and only four states still stand. This is like the doctor who visits more than ten thousand patients but cures only four; such a one cannot be called a good doctor.”20 Laozi’s model of the ideal world order is based on many small, weak states, not on strong, big states. He holds that if all states returned to the primitive era of recording events on knotted cords and the contacts between states were reduced, then the conflict between states would be reduced, and so he advocates small states with small populations. He says, “Let the people tie knots and use them, enjoy their food, embellish their dress, repose in their homes, rejoice in their customs. Neighboring states will look across at one another, calls of chickens and dogs will reply to one another. The people will reach old age and die but not communicate with others.”21

Guanzi and Hanfeizi conduct their analyses largely at the level of the state. The starting point of their analyses is the state or the ruler, state and ruler being generally interchangeable. Guanzi and Hanfeizi both hold that relative power is the deciding factor in the rise and fall of states and in interstate relations. Guanzi says,

Having perfected their own states while neighboring states are without the Way is a major asset for becoming a hegemon or sage king. … The early sage kings were able to reign as sage kings because the neighboring states made wrong decisions.

There are conditions that mark out the hegemons and sage kings. They are superior in moral virtue, in wise stratagems, in war—knowing the terrain and moving accordingly—and thus they reign.22 Hanfeizi believes that human beings are selfish; hence, conflict cannot be eliminated and only if a state is strong can it uphold state interests. He maintains that the strength and size of a state are dependent on its legal governance: “There is no constant strength or constant weakness for a state. If the one who makes the law is strong, then the state will be strong. If the one who makes the law is weak, then the state will be weak.”23 He constantly reiterates that the authority of the state is the foundation, and even holds that diplomacy is of no help in making a state strong and large: “If today one does not exercise law or administrative techniques domestically while using one’s wisdom externally, then one cannot arrive at strong governance.”24

The method of analysis employed by Confucius and Mencius is on the level of the individual person, specifically, the ruler. Confucius believes that the stability or instability of the world order is wholly determined by the moral cultivation of the political leader. He maintains that the personal virtue of the leader is the foundation of social order. Hence, he says, “If for one day one can overcome oneself and return to rites, then all under heaven will accept one’s benevolent authority.”25 Again, “By cultivating yourself you can bring peace to the common people.”26 Mencius inherited Confucius’s analysis at the level of the individual person. He ascribes the presence or absence of world order and the survival of states to whether the ruler has implemented benevolent governance, not simply to the ruler’s own moral cultivation. He holds that the reason the first kings of the three dynasties of Xia, Shang, and Zhou rose to leadership of their states whereas the three last kings of the same dynasties lost their positions was that the former governed benevolently and the latter did not: “The three dynasties acquired all under heaven by benevolence and they lost it through lack of benevolence. This is the reason why states decline or flourish, rise or fall.”27

Xunzi’s analysis is largely at the individual level. In analyzing the nature of international society, Xunzi regards the nature of the ruler of the leading state and his ministers as an independent variable—that is, whether international society is that of a sage king or a hegemon is determined by the nature of the ruler of the leading state and his ministers: “Those who follow the principle of humane authority and work with subordinates of humane authority can then attain humane authority; those who follow the principle of hegemony and work with subordinates of hegemony can then exert hegemony.”28

Sometimes Xunzi also injects analysis from the perspective of the social system. He sometimes argues that human society is communal; hence, unless there are hierarchical norms, conflict will inevitably arise. To uphold interstate order it is necessary to establish hierarchical norms: “The life of human beings cannot be without communities. If there are communities without distinctions, then there will be conflict, and if conflict then disorder, and if disorder then poverty. Hence, the failure to distinguish is the bane of human life, whereas having distinctions is the basic good of all under heaven.”29

Materialist Determinism and Conceptual Determinism

In stressing the standard of the role of matter or that of concepts, we can separate these seven philosophers into three groups. Hanfeizi is a committed materialist determinist; Guanzi and Xunzi are material and conceptual dualists; and Laozi, Confucius, Mozi, and Mencius are conceptual determinists.

In his examination of the causes of social conflict and recognition of state relations, Hanfeizi is always a materialist. He holds that because times change, material resources cannot satisfy needs, and hence conflict arises within humankind, and rewards and punishments are not able to eliminate it; hence, conflict between states cannot but rely on material forces: “Therefore, when the population increases and goods grow scarce, the energy expended to get by is taxing but the rewards reaped are paltry, so the people strive against one another. Even if you increase rewards and lay on punishments you will not prevent disorder. … Thus I say that as circumstances change so the means of dealing with them vary. In the remote past, conflict was decided by morals; in the recent past, it was decided by clever stratagems; today, conflict is decided by strength.”30

Guanzi is a material and conceptual dualist. Guanzi holds that international order and interstate relations are determined both by relations between human beings’ material interests and by conceptual thought. He holds that to maintain a stable international order both material power and moral thought are necessary. Either one alone is insufficient: “If virtue does not extend to the weak and small, if authority does not overawe the strong and great, if military expeditions cannot bring all under heaven to submission, then it is unrealistic to seek to be hegemon over the feudal lords. If one’s own authority is matched by like authority in another state, if one’s control of the military is challenged by others, if one’s virtue cannot embrace distant states, if one’s commands cannot unify the feudal lords, then it is unrealistic to seek to reign over all under heaven.”31

Xunzi is a moderate conceptual determinist. He sees the ideas of the ruler and chief ministers as the driving force behind state conduct, and therefore the cause of change in a state’s status is dependent on the ideas of the ruler and chief ministers. He thinks that the ruler’s ideas lead him to choose chief ministers, and this causes changes in a state’s status: “By practicing the norms of humane authority and employing humane people, one may attain humane authority. By practicing the norms of hegemony and by employing hegemonic people, one may attain hegemony. By practicing the norms of a dying state and employing people of a dying state, one will perish.”32 Nevertheless, Xunzi’s analysis of the cause of conflict resembles that of a dualist. He sees both human desires and material scarcity as the roots of conflict between states: “When people desire the same goods, their desire will be for more than the goods, and then a scarcity of goods will bring about rivalry.”33 At the same time, he sees a class system as an intervening variable in determining the possibility of conflict between states. He holds that if there are no norms for class distinctions, then people will fight over everything. He says, “The life of human beings cannot be without communities. If there are communities without distinctions, then there will be conflict.”34

Mozi, Confucius, and Mencius all analyze interstate relations in terms of concepts, but they frequently link concepts to the system. Mozi holds that what leads to interstate conflict is that people have failed to love others, and at the same time he holds that there is no system such that people’s thought can be unified to meet in a correct point of view. He says, “Examine where disorder comes from. It comes from failing to love each other.”35 And, “It is clear that all under heaven is disordered when there is no political leader to unify everyone’s thoughts with a correct view.”36 Confucius and Mencius believe that the basic influence on state relations is the moral outlook of the ruler. Morality as a variable has two values: benevolence and nonbenevolence. Confucius believes that the leader may rely on morality to bring distant peoples to submission: “If distant people do not submit, then cultivate benevolent virtue so as to attract them.”37 Mencius says, “If the Son of Heaven is not benevolent, he cannot retain what is within the four seas. If the feudal lords are not benevolent, they cannot retain their state altars of grain. If ministers are not benevolent, they cannot retain their ancestral temples. If the officials and ordinary folk are not benevolent, they cannot retain their arms or legs.”38 Confucius and Mencius both affirm the role of the system (rites), but they believe that benevolence is the foundation of rites—that is, that a concept is the foundation of the system.

Laozi is perhaps the purest conceptual determinist. He ascribes interstate conflict to people’s attitude to, and idea of, life. He says, “There is no greater disaster than not knowing how to be satisfied; no greater misfortune than wanting more.”39 He holds that if at the level of thought people can reduce their desires and be satisfied with the simple life of a small state, and if they fear death and therefore do not dare to travel far, the boats and weapons that could have been used in war will no longer be of use and thus there will be no more violent conflict: “In a small state with few people let there be weapons for tens and hundreds but they shall not be used; let the people so fear death that they shall not travel far. If then there be boats and carriages, yet no one will ride in them; if then there be armor and weapons, yet none will display them.”40

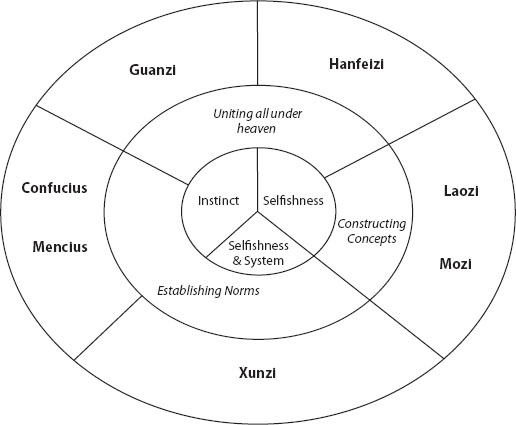

INTERSTATE ORDER

In the works of the pre-Qin masters there is much about the causes of war and the ways to implement peace. Since their understanding of the nature of war differed, their views of whether it was just and the role of morality in upholding interstate order also differed. On this issue of war and peace I group the seven thinkers according to figure 1.1. In the inner circle are the causes of war, in the middle circle are the paths to peace, and in the outermost circle are the masters themselves. From this figure we discover that there is no necessary connection between the causes to which the masters ascribe the outbreak of war and the paths to peace.

Figure 1.1 The causes of war and maintenance of peace

Interstate Conflict and War

The seven thinkers discussed in this essay can be grouped into three categories as regards their views of human conflict and war. Laozi, Mozi, and Hanfeizi believe that the cause of human conflict is the selfishness of original human nature; Xunzi believes that the cause lies in selfishness itself and in a lack of order; Guanzi, Confucius, and Mencius believe that it arises from human beings’ animal survival instinct.

Laozi, Mozi, and Hanfeizi believe that the cause of conflict is the selfishness of original human nature. Laozi holds that the greatest sin is the rapacious mind and this mind is what leads men to fall into war. He says, “When all under heaven is without the Way, warhorses must give birth outside the city. There is no greater disaster than not knowing how to be satisfied; no greater misfortune than wanting more.”41 Since he sees war as the result of a rapacious mind, he views war as a crime: “Weapons are inauspicious instruments. Things like these are such that there are those who detest them. Hence one who has the Way does not touch them.”42 Mozi also looks at the cause of war from the point of view of the selfish human mind. He attributes war to people loving only their particular states rather than the world as a whole: “Each prince loves his own state and does not love others’ states; hence they attack other states so as to benefit their own.”43 Hanfeizi also attributes violent conflict to the selfish nature of humankind. But he explains conflict from the failure of material goods to meet demand: “Therefore, when the population increases and goods grow scarce, the energy expended to get by is taxing but the rewards reaped are paltry, so the people strive against one another.”44 He maintains that private interest is the basic motive for state behavior and a state’s greatest private interest is to possess hegemonic power. He says, “to be a hegemonic king is a great benefit for the lord of men.”45 Human selfishness is, for him, the reason why interstate war is unavoidable. Some people claim that Laozi and Hanfeizi differentiate between just and unjust wars.46 In fact, however, neither of them is concerned about whether wars are just or unjust. Laozi disapproves of all war, believing that all wars are bad; hence his saying, “One with the Way does not touch them.”47 Because all wars are bad, he does not judge their justice or injustice. In contrast, Hanfeizi does not ask if the purpose of a war is just or not; he is only concerned to know if it is victorious or not:

To make war and be victorious is to bring peace to the state and stability to one’s own royal person; the army will be strong and your awe-inspiring reputation established. Even if later you have more opportunities, none will be as great as this one. What gains of ten thousand generations should you worry about after winning the war? To make war and not be victorious is to annihilate the state and weaken the army, you are slain and your reputation extinguished. Even if you want to avoid the present defeat, you will not have a chance to do so, still less can you hope for the gains of ten thousand generations.48

Xunzi does not deny that selfishness is the cause of human conflict, but he thinks that if there are the constraints of a social system, then conflict can be avoided. There are scholars who hold that Xunzi sees the pursuit of material gain as the source of conflict, but in fact Xunzi sees human selfishness and the lack of systematic hierarchical norms as the joint causes of war.49 He says, “when the powers exercised by two people are equal and their desires are the same, then since goods cannot satisfy them there will be conflict.”50 Both Xunzi and Hanfeizi concur in believing that human nature is basically bad and the violent conflict inspired by profit seeking is an inevitable feature of society. Xunzi says, “Now the nature of man is such that from birth he tends toward gain. He follows this inclination, and hence competition and rapacity ensue, while deference and yielding are discarded. … Now to follow human nature and go along with human inclinations must lead to competition and rapacity, and be concordant with opposition to distinctions and to disrupting principles and so lead to violence.”51 Xunzi’s theory that human nature is bad and Mencius’s rival theory that it is good rely on different logics. When Xunzi speaks of selfishness, he means desire for material goods, unlike Mozi. Mozi’s “lack of mutual love” is an abstract kind of selfishness. The difference between Xunzi and Laozi, Mozi, and Hanfeizi lies in Xunzi’s belief that some wars are just and some are unjust. He says that the purpose of a just war is to stop violence and uproot evil; hence, “the armies of the benevolent circulate under heaven.”52

Neither Guanzi, nor Confucius, nor Mencius directly tackles the issue of the origins of violent conflict among human beings, but they all see war as an instrument. We may assume that they think that the cause of violent conflict is the struggle for human survival itself. Moreover, this struggle for survival is not equivalent to selfishness. It is part of man’s animal nature whereas selfishness is a matter of his social nature. Neither Guanzi nor Confucius discusses whether human nature is selfish. While acknowledging that war is not a moral instrument, Guanzi nonetheless accepts that it can serve various political ends. He says, “One who plots for military victories will attain hegemonic authority. Now, although arms are not up to the Way or virtue, yet they can assist a sage king and bring success to a hegemon.”53 Confucius holds that war and humankind have always been present together, and he takes the example of the aggressive nature of wasps and scorpions to explain how human beings use weapons in self-preservation, this being part of their survival kit. When Duke Ai of Lu asked Confucius how war came about in ancient times, Confucius said, “The origins of wounding lie far back. It was born along with mankind. … Wasps and scorpions are born with a sting. When they see danger they make use of it so as to protect their bodies. Human beings are born with joy and anger; hence, weapons arise, and they came into being at the same time human beings did.”54 Some claim that Confucius and Mencius advocate “no war” and are opposed to all war.55 In fact, they are not opposed to all war, only to unjust wars. They support just wars. Confucius assesses the justness of a war by its purpose: “The sage uses troops to put down inhumanity and stop violence under heaven, but later generations of rapacious persons use troops to kill the ordinary people and put states in danger.”56 Mencius asserts the goodness of human nature and therefore does not ascribe the cause of war to human selfishness. He uses the terms punishment and attack to distinguish between just and unjust war: “The Son of Heaven decrees punishment but does not inflict it; the feudal lords inflict punishment but do not decree it.”57 And, “In the Spring and Autumn Period there were no just wars.”58 Mencius also differentiates between just and unjust wars, showing that he believes that war is an instrument designed to implement justice or injustice and that it is a tool humans use to realize their goals.

Interstate Order and Peace

The pre-Qin masters’ understanding of the causes of war and their preference for implementing the ways of peace are not wholly uniform. Laozi and Mozi believe that peace can be realized by constructing concepts; Confucius, Xunzi, and Mencius believe that human behavior can be restrained by systematic norms and by this means peace can be achieved; Guanzi and Hanfeizi think that it is necessary to increase strength so as to attain peace for one’s own state.

Laozi and Mozi both think that it is possible to avoid war by changing people’s ideas, but the ideas each seeks to change are quite different. Some people think that Laozi advocated small states with small populations, because if the world were composed only of small states there would be no large states desirous of making war on small states.59 In fact, Laozi attributes the cause of conflict to human selfishness and believes that this selfishness cannot be eliminated; he thinks that forcing people to fear death and enjoy life will cause them not to wish to go out, thereby reducing interaction between groups of people and, hence, reducing conflict:

In a small state with few people let there be weapons for tens and hundreds, but they shall not be used; let the people so fear death that they shall not travel far. If then there be boats and carriages, yet no one will ride in them; if then there be armor and weapons, yet none will display them. Let the people tie knots and use them, enjoy their food, embellish their dress, repose in their homes, rejoice in their customs. Neighboring states will look across at one another, calls of chickens and dogs will reply to one another. The people will reach old age and die, but not communicate with others.60

He believes that forcing people not to seek progress will help in preventing conflict: “In governing human beings, empty their minds, fill their bellies, weaken their will, strengthen their bones, always make it such that the people know nothing and desire nothing, so that the knowledgeable will not dare to act.”61 Laozi’s thought reminds one of Francis Fukuyama, who claims that the better conditions of life in developed countries are such that young people have no great passions and, hence, developed countries do not think of going to war.62

The stress Mozi puts on the human fear of death and demand for no progress is the exact opposite of what Laozi says. Mozi advocates diminishing human beings’ selfish psychology and replacing it with an altruism of loving one’s neighbor as oneself and thereby avoiding war. Mozi believes that human selfishness is a necessary condition for war and so by changing human beings’ selfish nature—such that they love others as themselves—peace will be realized. Mozi says, “Look at the state of others as one’s own. … Therefore, if the feudal lords love one another there will be no savage wars.”63 Mozi thinks that to bring about this idea of loving one’s neighbor as oneself one must establish a structural system, that is, a system that can unify people’s way of thinking. In this way the government’s advocacy of the spirit of loving one’s neighbor as oneself can be transformed into an idea of the whole society. He thinks that when there is a system by which “the superiors affirm something, then everyone will affirm it, and if they deny something, then everyone will deny it.”64 In such a system, it would be possible to construct a universal idea of loving one’s neighbor as oneself. Hence, he says, “Examine how all under heaven is governed. If the Son of Heaven can but unify the thoughts of all under heaven, then all under heaven is governed.”65

The Confucians—Xunzi, Confucius, and Mencius—think that only by establishing norms (rites) for class distinctions can social order be upheld, but the norms that each proposes differ. Xunzi ascribes the cause of war to human selfish desires and to a lack of norms for class distinctions. He thinks that there is no way to eliminate selfish desires and hence one must rely on authoritative norms that allocate resources to each class: “Hence failure to make distinctions is the bane of human life, whereas having distinctions is the basic good of all under heaven. The ruler is the key to the management of distinctions.”66 The norms that Xunzi speaks of are the authoritative norms that allocate resources to each class. He says, “The early sage kings hated disorder and so they determined the distinctions of rites and norms, so that there were the grades of rich and poor, high and low status, sufficient so that there could be mutual oversight. This is the root for fostering all under heaven.”67 Xunzi thought that norms for classes would ensure the rightful authority of the feudal lords but would also set limits to that authority. Hence, by having norms the princes could check on one another and each be at peace with the others. Confucius thought that the conduct of the feudal lords could be restrained by the moral norm of benevolence and in this way interstate order could be upheld: “If the superior likes rites then the people will easily go along with him.”68 And, “To overcome oneself and return to rites is benevolence. If for one day one can overcome oneself and return to rites then all under heaven will accept one’s benevolent authority.”69 The rites that Confucius refers to are the moral norms to uphold benevolence and justice. This is different from Xunzi’s understanding. Mencius has no discussion of how to uphold peace but we can assume that his ideas on this are similar to those of Confucius.

Guanzi and Hanfeizi think that long-lasting peace is impossible; they merely discuss how to strengthen a state so as to uphold its own peace. They differ in their views on the causes of war. Guanzi ascribes it to human survival instinct whereas Hanfeizi attributes it to human selfishness, but they both see war as an instrument for realizing the good of the state and both hold that the peace of the state comes from exerting military power over other states. Guanzi says, “If war is not won and defense is not firm, then the state will not be secure.”70 Hanfeizi thinks that the cause of conflict is that material goods cannot satisfy demand, but he does not think that systematic norms are able to prevent conflict. He says, “Even if you increase rewards and lay on punishments you will not prevent disorder.”71 He thinks that force is the only thing that can preserve a state’s peace. He says, “Hence when a state has greater force, then no one under heaven will be able to invade it.”72 Since force is the basis of peace, neither Guanzi nor Hanfeizi can avoid the conclusion that the stronger will constantly make war on the weaker. Guanzi thinks that the strong state will use war to enhance its international status. He says, “The importance of a state will depend on the victories of its armies; only then will the state be firm.”73 Hanfeizi puts it even more plainly: “A small state must listen to the demands of a large state; weak troops must submit to the advances of strong troops.”74 Following the logic of Guanzi and Hanfeizi, it is only by using military force to unify everything under a world government that it is possible to realize universal peace. Neither Guanzi nor Hanfeizi discusses whether it is possible to prevent war when two states are evenly balanced in power.

In general, the pre-Qin thinkers hold that morality and the interstate order are directly related, especially at the level of the personal morality of the leader and its role in determining the stability of interstate order. If morality and violent force are taken as two functions by which international order is upheld, then we may divide the seven thinkers considered in this essay into three groups. Hanfeizi believes that only in special circumstances does morality play a role in upholding interstate order, whereas normally violent force is the sole factor in play. Guanzi, Laozi, Confucius, Xunzi, and Mencius believe that morality is a necessary condition for upholding interstate order, but they are not opposed to the use of violent force to maintain order. Mozi, by contrast, holds that morality alone is sufficient to maintain interstate order because, to him, morality implies a rejection of violence.

Hanfeizi has been held as denying the role of morality and his observation, “In the remote past, conflict was decided by morals; in the recent past, it was decided by clever stratagems; today, it is decided by strength,” has been quoted as proof. Yet he does not unconditionally reject the role of morality in upholding interstate order; rather, he thinks that the role of morality is founded on two presuppositions: first, that the main threat facing humankind is not from other human beings but from wild animals and illnesses, and second, that basic needs for clothing and food are met:

In the remote past, people were few but birds and beasts were many. People could not overcome the birds, beasts, insects, or snakes. A sage arose who fashioned wood into nests so as to avoid the many ills and the people liked this and made him reign over all under heaven, calling him “nest-builder.” The people ate fruit, gourds, mussels, and clams; the stink hurt their stomachs and the people suffered many illnesses. A sage arose who struck a flint in tinder and made fire so as to transform the putrid foods, and the people liked this and made him reign over all under heaven, calling him “tinder man.” … In the remote past men did not plow, the fruit of plants and trees sufficing for their food; women did not weave, skins of birds and beasts sufficing for their clothing. Because they did not exert any force and yet were fed and clothed sufficiently, people were few in number and goods were more than enough; hence, people did not fight. Therefore rich presents were not distributed nor were heavy punishments administered, and the people regulated themselves.75

He thinks that when threats to security come from human beings themselves and the basic requirements of food and clothing are not met sufficiently, then morality loses its role in maintaining order.

Guanzi, Laozi, Confucius, Xunzi, and Mencius believe that morality is the key factor in upholding interstate order. For Guanzi, morality is quite simply a necessary condition for international leaders. Only when a leader exercises morality toward other states can interstate order be upheld: “One who wants to employ the political authority of all under heaven must first extend virtue to the feudal lords.”76 Confucius thinks that raising the moral standing of the leaders will result in distant states that had not submitted to their rule coming to heel: “If distant people do not submit, then cultivate benevolent virtue so as to attract them.”77 Xunzi thinks that if the morality of the leaders of the leading states in the world is high, then all under heaven will avoid disorder. The reason for all under heaven being disordered is that the leaders are not up to scratch: “Let morality be whole and attain the highest peak; cultivate civilized principles and unify all under heaven. If you then but touch the tip of a hair there is no one under heaven who will not submit. This is the business of the heavenly king. … If all under heaven is not united and the desires of the feudal lords are opposed, then the heavenly king is not the appropriate person for the post.”78 Mencius believes even more that morality is the key to maintaining interstate order: “Should you make people submit to force rather to the heart, force will never suffice; should you make people submit to virtue, they will heartily rejoice and sincerely follow as the seventy disciples followed Confucius.”79

Laozi distinguishes between the roles the Way and virtue play in upholding interstate order. Laozi thinks that the Way is the foundation of peace: “When the Way exists under heaven, then running horses are kept for their manure.”80 By this he means that when the world has the Way, then horses are detached from their war chariots and taken to the fields to provide manure and there is no need to go to war anymore. He interprets “virtue” as an application of the Way. As he puts it, “The Way generates them [the myriad things]; virtue nourishes them.”81 He thinks that the higher the “virtue” of the Way a political leader implements, the larger the group of people the “virtue” will reach and the more broadly it will extend. He says, “when practicing it [virtue] in the state, one’s virtue is abundant; when practicing it in all under heaven, one’s virtue is universal.”82 Given the relationship between the Way and virtue that Laozi sees, a political leader who has virtue can realize the Way and thereby uphold interstate order.

Even though these five thinkers all believe that morality is the key to maintaining order between states, they also hold that to speak of morality does not imply a total rejection of violent force to uphold order. Guanzi holds that the morality of world leaders includes gentleness toward the obedient and punishment of the recalcitrant. In other words, to fail to punish someone who disrupts interstate order is immoral. He says, “The double-faced were punished by war; the obedient were sheltered by civil ways. When both war and civil conduct were implemented there was virtue.”83 Confucius thinks that reliance on preaching to uphold the norms of benevolence and justice is inadequate. Hence he thinks that the way of war should be employed to punish the princes who go against benevolence and justice. For example, he recommends that Duke Ai should militarily punish the state of Qi for undertaking a political revolution.84 Xunzi even goes so far as to think that talking about morality does not exclude using military force to annex other states. He says, “A humane authority militarily punishes only those who are unjust and never lays siege to others unjustly. … Thus people in disordered states dislike their own governments but like the humane authority’s governance and welcome his military occupation.”85 Mencius thinks that using just war to uphold the norms of benevolence and justice between states is lawful. He says, “It is permissible for the minister of heaven to punish those without the Way.”86 The idea of these four philosophers that just war can be used to uphold international order still has a great influence today. The fifth master, Laozi, thinks that only when it is unavoidable should war be used to uphold order between states, although war itself cannot be said to be just. Hence he says, “Weapons are inauspicious instruments, not the instruments of the gentleman. They may be used only when unavoidable; calm restraint is superior.”87

Mozi affirms that morality can be an effective way of maintaining order among states. Moreover, he thinks that the mention of morality should preclude resort to violence as a means of upholding that order. He is astonished that policy makers do not know what morality is. Policy makers do not apply the domestic norms of morality to interstate matters; hence, interstate order is unable to attain the degree of stability that is found within a state. Mozi notes that people generally look on individual thieves, brigands, and murderers as unjust, but when it comes to the invasion of states, annexation, and war, these phenomena are paradoxically designated as just. It is a failure to apply morality to interstate issues that causes disorder at this level: “Now what is small and wrong is said to be wrong and this is known to be so. Hence it is condemned. What is big and wrong—such as attacking states—is not known to be wrong and so people go along with it and praise it, saying that it is just. Can this be said to be knowledge of the difference between what is just and what is unjust? Therefore it is known that exemplary persons under heaven are confused in their distinction between just and unjust.”88

LEADERSHIP AMONG STATES

The pre-Qin masters generally thought that order among states was determined by the nature of their leaders, and therefore they regularly invoked the concepts of “all under heaven” and “to reign as a sage king.” Moreover, these two concepts are often joined into one: “to reign over all under heaven.” Pre-Qin people did not have the idea of the Earth as a globe; they thought the Earth was square and flat. They did not know that there were lands not joined to the mainland, nor did they know that in other lands there were other people and civilizations. Hence, conceptually speaking, the “all under heaven” of pre-Qin people and today’s “world” have two points in common: one is that the Earth is understood to include the whole surface of the land beneath heaven; the other is that it is limited to the totality of social relationships among human beings. The pre-Qin expression “to reign over all under heaven” and our modern expression “to attain hegemony over the world” have both similarities and differences. Moreover, like today’s thinkers, pre-Qin people had many different notions of what “all under heaven” or the “world” was and they also differed in their understanding of “humane authority” and “hegemonic authority.” With respect to their attitudes to all under heaven and to humane authority, we may classify the differences among the seven thinkers according to table 1.2.

The Nature of All under Heaven and the Basis of Humane Authority

The Nature of All under Heaven

We can classify the pre-Qin thinkers discussed in this essay into four groups depending on their answer to the question whether all under heaven and the state share the same nature. Mozi and Hanfeizi think that the authority of the state and all under heaven share a common nature; Guanzi holds that they are dissimilar; Confucius, Mencius, and Xunzi think that the state is a matter of power and all under heaven is a moral authority, and hence they are different in nature; Laozi thinks that the difference between state and all under heaven lies in the former being secular and the later being transsecular.

Hanfeizi and Mozi both think that all under heaven is the state writ large and so power over them is the same in nature. They think that there are four progressively larger social organizations—family, feudal town, state, and all under heaven—and these four are similar in nature. It is only the scale that differs. Hanfeizi looks at the state and all under heaven as issues of political power and believes that power alone suffices to annex all the states existing in all under heaven into one. In addressing King Zhao of Qin, he talks about the advantages of terrain, saying, “The commands and ordinances, rewards and punishments of Qin, the advantages of its terrain are unlike any [other state] of those under heaven. By relying on these to gain all under heaven, it can easily be annexed and possessed.”89 Mozi believes that power over the state and power over all under heaven are similar in nature, and by using the same methods of governance they can obtain the same results. He says, “Governing the states under heaven is like governing a household,”90 and again, “When a sage governs a state, then its income is doubled; when he governs something as big as all under heaven, all under heaven’s income is doubled.”91

Guanzi thinks that all under heaven and the state both have to do with political power, but different kinds of political power, and so they cannot be grasped in the same way. Guanzi holds that family, local community, the state, and all under heaven are different levels of the social unit and they are essentially different and hence the method of governing each is distinct: “Trying to run the district like a household, the district cannot be run. Trying to run the state like a district, the state cannot be run. Trying to run all under heaven like a state, all under heaven cannot be run.”92 Guanzi believes that acquiring all under heaven is not equivalent to unifying all under heaven, but rather is to allow each feudal state to willingly obey, and so acquiring all under heaven relies not only on power but especially on exercising morality toward the feudal states. He says, “One who wants to employ the political authority of all under heaven must first extend virtue to the feudal lords. In this way, the first sage kings were able to gain and to give, to retract and to win trust, and thus they could employ the political authority of all under heaven.”93 And, “It was political skill by which the first sage kings acquired all under heaven, political skill that amounted to great virtue.”94

Confucius, Xunzi, and Mencius think that there is an essential difference between the state and all under heaven: the former has to do with political power whereas the latter has to do with moral authority. Confucius thinks that all under heaven is composed of many states and that all under heaven and the state are different concepts: “Hence sages used rites to show them; hence all under heaven and states could be acquired and ruled correctly.”95 This statement shows that Confucius sees all under heaven and the state as two different political units. He thinks that all under heaven is owned by all humankind: “The working of the great Way is for all under heaven to be owned by all.”96 Because the Son of Heaven is the representative of heaven:

Under heaven’s canopy there is nowhere that is not the sage king’s land;

Up to the sea’s shores there are none who are not the sage king’s servants.97

Confucius thinks that all under heaven should be seen as having to do with moral authority, and so the rulers of states may not do what the Son of Heaven—who represents heaven—can do: “None but the Son of Heaven may determine rituals, fix measurements, and decree the form of writing.”98 He even thinks that whoever carries out inspections—whether it is the Son of Heaven or the feudal states—to enforce interstate norms and undertake military expeditions, is an indicator of whether there is moral authority under heaven: “When all under heaven has the Way, then rites, music, and punitive expeditions proceed from the Son of Heaven; when all under heaven is without the Way, then rites, music, and punitive expeditions proceed from the feudal lords.”99

Xunzi thinks that the state is a matter of political power and hence both moral and immoral persons may strive to obtain it and use it, but all under heaven is a matter of moral authority and only the sage may enjoy it and use it: “The state is a small thing and a small-minded person may possess it. A person little gifted with the Way can obtain it and it can be held by little force. All under heaven is a huge thing. It cannot be possessed by the small person nor can it be obtained by a person little gifted with the Way, nor held by only a little force. A state can be held by a small-minded person but it cannot exist forever. All under heaven is the greatest and no one but a sage can hold it.”100 He particularly stresses that because the state is a matter of power, people who strive may be able to gain hold of it, whereas because all under heaven is a matter of authority, it cannot be acquired by striving for it. The authority of all under heaven is automatically reserved for the sage: “Tang and Wu did not seize all under heaven … all under heaven accrued to them. Jie and Zhòu did not lose all under heaven … all under heaven left them.”101 Hence, Xunzi says, “It is possible for a state to be stolen from others; it is not possible for all under heaven to be stolen from others. It is possible for states to be annexed but it is not possible for all under heaven to be annexed.”102 Mencius argues in a similar vein: “There are those lacking benevolence who have acquired states; but there has never been anyone lacking benevolence who acquired all under heaven.”103 We can compare the authority of the Pope in the Vatican and that of the military junta in Myanmar to understand the distinction Xunzi and Mencius make between ‘all under heaven’ and ‘states.’

Laozi thinks that all under heaven has to do with transsecular authority and hence is totally different from the secular state. Acquiring state power and acquiring all under heaven cannot be achieved in the same way. All under heaven naturally accrues to one. In this Laozi shares the view of Xunzi. Laozi says, “Govern the state by orthodox methods; use troops in unorthodox ways; acquire all under heaven by undertaking nothing.”104 He even holds that not only can human striving not acquire all under heaven, but no one can hold it: “I have seen that it is not possible to acquire all under heaven by striving. All under heaven is a spiritual vessel and cannot be run or grasped. To try and run it ends in failure; to try and grasp it leads to losing it.”105

The Foundations of Interstate Leadership

Pre-Qin thinkers generally believed that there were two kinds of interstate leadership, humane authority and hegemonic authority. Among the seven pre-Qin thinkers discussed in this essay, Hanfeizi and Mozi thought that there was no great difference in substance between humane authority and hegemonic authority; Guanzi, Mencius, and Xunzi thought that there was a difference; and Confucius, and Laozi have no discussion of whether the two differed.

Hanfeizi thought that hegemonic authority and humane authority were alike in nature. In his exposition, he often links the terms hegemon and sage king as in “the titles of hegemons and sage kings,” “the Way of hegemons and sage kings,” “one who is a hegemon or sage king.” This shows that he does not think there is any difference in nature between the two. Unlike the other pre-Qin thinkers, he does not think that the foundation of humane authority is morality. He holds that in ancient times humane authority was upheld by morality, but with changes of the times the system of humane authority now no longer relies on morality for support: “Of old King Wen practiced benevolence and justice and reigned over all under heaven; King Yan practiced benevolence and justice and lost his state, which goes to show that benevolence and justice were of use in the past but are of no use today.”106 He thinks that the kernel of humane authority and hegemonic authority is to bring the states of the feudal lords to submit: “If the feudal lords round about do not submit, then the title of hegemon or sage king is unfulfilled.”107 Because of this, he thinks that humane authority is also dependent on military might and a legal system. He says, “A sage king is able to attack others.”108 “Hence making the law is the basic task of a sage king.”109

Mozi uses the term sage king more than the term hegemon, but he does not indicate whether there is any distinction between them. Rather, he uses historical examples of humane authority and hegemonic authority to explain the same principle. Mozi’s understanding of humane authority is very secular. He sees humane authority as a matter of social accumulation, a form of social prestige, and he thinks that this prestige is born from the government’s carrying out policies that are beneficial to the people. He thinks that the sages established the institution of humane authority because it is of benefit to the people and hence it exists for their good. He says, “Of old the enlightened kings and sages were able to reign over all under heaven, and direct the feudal lords because their love for the people was sincere. Loyalty joined together with trust and led to benefits. Therefore, throughout their lives no one hated them, and up to their deaths no one tired of them.”110 Mozi thinks that Shun, Yu, Tang of the Shang Dynasty, and King Wu of the Zhou exercised humane authority whereas Duke Huan of Qi, Duke Wen of Jin, King Zhuang of Chu, King Helü of Wu, and King Goujian of Yue exercised hegemonic authority, but he does not say what the difference between them was. He thinks that what the two have in common is that they are founded on a policy of employing worthy and capable persons: “What the former four kings were influenced by was correct, and hence they reigned over all under heaven. … What these five princes were influenced by was correct and so they held hegemony over the feudal lords.”111 This says that the four sage kings and the five hegemonic lords were all influenced by worthy people and hence able to reign or become hegemons. Mozi ascribes the establishment of humane authority and hegemonic authority to the exclusive use of worthy people and the standard of worthiness is that they bring benefits to the people.

Guanzi thinks that the core difference between hegemonic and humane authority lies in the presence or absence of moral ability in the leading state. He thinks that what royal and hegemonic authority have in common is powerful material power and where they differ is that humane authority has the ability to correct the errors of other states whereas hegemonic authority lacks this. He thinks that humane authority can correct the errors of other states because it comes from a superior moral status, not because of any material power. He says, “One who enriches his own state is called a ‘hegemon.’ One who unifies and corrects other states is called a ‘sage king.’ The sage king is gifted with clear vision. He does not take over states of like virtue; he does not reign over those who go the same Way. Among those who contend for all under heaven, a sage king usually conquers violent states with authority.”112 He also says, “One who is conversant with virtue will attain humane authority; one who plots for military victories will attain hegemonic authority.”113 He thinks that humane authority and hegemonic authority can be attained by making an effort, but because the moral prestige of humane authority is high, it can attract the majority of states to follow it, whereas, given that the moral prestige of hegemonic authority is correspondingly less, only half of the states will submit to it: “The one who wins over the majority of all under heaven enjoys humane authority; the one who wins over only a half enjoys hegemonic authority.”114

Mencius thinks that the root difference between humane authority and hegemonic authority is that the former relies on morality and the latter on power to uphold interstate order. He thinks that hegemonic authority relies on power whereas humane authority relies on a stronger form of morality for its maintenance and can survive without a particularly large material force. He thinks that the standard for differentiating between humane and hegemonic authority lies in the purpose for which the ruler upholds his power, not in the amount of his strength. Hegemonic authority borrows the slogan of benevolence and justice to uphold its power whereas humane authority uses power to implement a policy of benevolence and justice. He says, “Using force and pretending to benevolence is the hegemon. The hegemon will certainly have a large state. Using virtue and practicing benevolence is the sage king. The sage king does not rely on having a large territory.”115

Xunzi thinks that both royal and hegemonic authority need the twin forces of power and morality, but that humane authority relies more on morality and hegemonic authority more on power. Xunzi uses the examples of King Tang of the Shang and King Wu of the Zhou, who reigned over states of a hundred square kilometers and upheld the order of all under heaven, to explain that morality is more important than material power in upholding the system of humane authority: “By practicing justice in their states, their fame spread in a day. Such were Tang and Wu. Tang had Bo as a capital, King Wu had Hao as a capital; each state was only ten thousand square kilometers, yet both kinds unified all under heaven and the feudal lords were their ministers; among those who received their summons, there were none who did not obey. There was no other reason for this but that they implemented norms. This is what is called ‘establishing norms and attaining humane authority.’”116 He thinks that the use of morality to uphold humane authority is a sign of a sage king, who chooses to act by moral norms and judges affairs by legal rules. He says, “The sage king acts according to rites and justice and makes clear judgments according to the applicable norms.”117 Xunzi thinks that, even though hegemonic authority relies mainly on material force for support, without the most basic political credibility it cannot be maintained:

Although virtue may not be up to the mark nor norms fully realized, yet when the principle of all under heaven is somewhat gathered together, punishments and rewards are already trusted by all under heaven; all below the ministers know what they can expect. Once administrative commands are made plain, even if one sees one’s chance for gain defeated, yet there is no cheating the people; contracts are already sealed, even if one sees one’s chance for gain defeated, yet there is no cheating one’s partners. If it is so, then the troops will be strong and the town will be firm and enemy states will tremble in fear. Once it is clear the state stands united, your allies will trust you. Even if you have a remote border state, your reputation will cause all under heaven to quiver. Such were the Five Lords. … This is to attain hegemony by establishing strategic reliability.118

In other words, even if the moral level of hegemonic authority is not high, at least one should speak the truth and be trusted by the people of one’s own state and by one’s allies. In those years, the five hegemons were all able to achieve this and thus they established their hegemony.

In the writings of Confucius and Laozi there is no clear discussion of the distinction between humane and hegemonic authority, but their attitudes to humane and hegemonic authority are very different. Confucius has a discussion of hegemonic authority but nothing about humane authority. From his affirmation of the role of Guan Zhong in establishing the hegemony of Duke Huan of Qi, we see two points about his understanding of hegemony. First, he thinks that hegemonic authority also needs morality; a mild use of military power to successfully rule as hegemon is benevolence. He says, “He gathered the feudal lords from the nine directions not by troops and chariots but by the strength of Guan Zhong. Oh! who has his benevolence! Who has his benevolence!”119 Second, Confucius thinks that hegemonic authority has the ability to determine the norms of the world. Subjectively one holds the hegemonic position while objectively the mass of the people benefit: “Guan Zhong served Duke Huan, who was hegemon over the feudal lords and unified all under heaven. The people have benefited from his grace up until today.”120 Confucius exalts the ancient sage kings, Yao and Shun, believing that they established their humane authority by their own moral cultivation. He says, “By cultivating themselves they could bring peace to the common people. Were Yao and Shun not concerned about not being up to this?”121 This is to say, by raising one’s own virtue and cultivation to comfort the ordinary people, even great moral leaders such as Yao and Shun were concerned lest they had not done enough. Since he thinks that humane authority is based on self-cultivation, Confucius thinks that Shun ruled all under heaven by nonaction. He says, “using nonaction to rule, was that not Shun?”122

Laozi discusses humane authority but not hegemonic authority. Laozi thinks that humane authority is a form of prestige that makes all under heaven submit and obey. Its foundation is the moral spirit of willingness to suffer for the people. He uses the example of the sea becoming the king of the rivers—because it is lower than any river—to explain that humane authority requires a willingness to put oneself at the bottom: “Rivers and seas are able to be the king of the hundred valley streams because they are good at choosing the low place and so they can be king over the hundred valleys.”123 He thinks that anyone in the world can attain royal power because he can accept the greatest disaster of a state. He says, “To accept disaster for the state is called being the lord of the altars of soil and grain; to accept destruction for the state is to be the sage king over all under heaven.”124 Because Laozi thinks that only by being willing to suffer on behalf of the multitude is it possible to attain humane authority, his logic is that to contend for humane authority betrays a selfish mind and a selfish person will not think of accepting suffering, so the people who think of contending for humane authority will not achieve it. He thinks that to attain humane authority one must rely on “not striving, for none under heaven may contend with him.”125

In this section, we have discovered that there is a very close correlation between how the pre-Qin thinkers understand the concept of all under heaven and how they understand humane authority (see table 1.2). Hanfeizi and Mozi think that all under heaven and the state belong to the same secular power; hence, they believe that increasing state power or increasing the benefits given to the people are the foundations of humane authority. Guanzi thinks that all under heaven differs from the secular power of the state and hence he sees the basis of humane authority as lying in the moral force that corrects states’ mistakes. Confucius, Xunzi, and Mencius think that all under heaven is a matter of moral authority and hence they talk about moral cultivation and implementation of benevolent government as the foundation of humane authority. Laozi thinks that all under heaven is a transsecular authority; hence he believes that the foundation of humane authority is the willingness to suffer on behalf of the people.

SHIFTS OF HEGEMONIC POWER

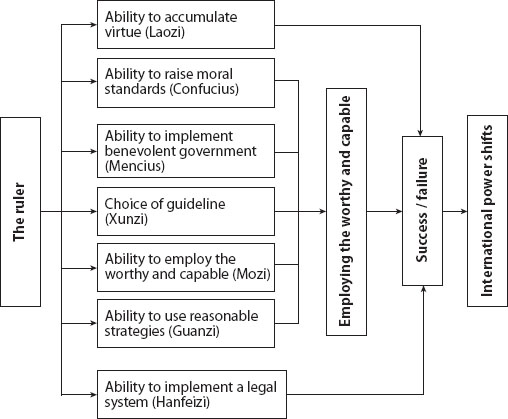

Shifts in hegemonic power are a constant topic in international politics. Pre-Qin thinkers also have something to say about the rise and fall of hegemons. Basically, they look at the rise and fall of hegemonic power in terms of state leadership and universally attribute it to political causes. It is very rare for pre-Qin masters to attribute it to economic causes, and no one ascribes it to the level of production. Yet, although they all speak in terms of political causes, they differ in their understanding of exactly which political factors are decisive.

The Power-Base of Interstate Leadership

The pre-Qin masters generally think that the power base of leadership among states is comprehensive and that elements of state power are not convertible. The classic position is outlined by Sima Cuo: “Someone who wants to enrich a state must enlarge its territory; someone who wants to strengthen the army must enrich the people; someone who wants to be a sage king must extend his virtue.”126 Pre-Qin thinkers generally believe that political, economic, and military factors are all important, but they also generally believe that political capability is the foundation that integrates comprehensive state power.

The pre-Qin thinkers discussed in this essay all believe that politics is the decisive factor in integrating state power. Guanzi says, “If a state is large and its governance small, the state will follow the governance. If a state is small yet the governance big, the state becomes large.”127 Laozi says, “By giving priority to the accumulation of virtue [you find that] there is nothing that cannot be overcome; when there is nothing that cannot be overcome, then none will know your limits; when none know your limits, then you can possess the state; when you possess the key to the state, then your state can last for a long time.”128 Mencius says, “If today, O King, you expand your governance and implement benevolence … who then can resist?”129 Xunzi says, “Hence those implementing the rites will attain humane authority and those stressing governance will be strong.”130 Hanfeizi says, “That by which a state is strong is politics.”131 Mozi thinks that the wealth or poverty and rise or fall of a state all depend on whether the employment of people in politics is appropriate. He sets out all the reasons why a state is not able to become rich and strong: “It is because in governing their states the kings, dukes, and great officials have not bothered to appoint the worthy and use the capable in their administration.”132 In discussing with his disciples what is important in governing a state, Confucius points out that the trust of the people is more important than supplies of food or the army.133

Even though the pre-Qin masters generally agree that politics is the basis for the strength or weakness of state power, they have different views as to what constitutes the core factor of political power. Laozi and Confucius both think this core factor is the ruler’s morality. Laozi thinks that accumulation of virtue by the leader is the key to survival of the state. He sees accumulation of virtue as “the way of being deeply rooted, firmly grounded, long-lived, and forever caring.”134 Confucius says, “Using virtue for governance is to be like the North Star: it holds its position and all the stars circle around it.”135

Mencius thinks that the core factor for political power is to implement a policy of benevolence and justice. He thinks that, on the basis of the leader’s own cultivation of virtue, it is also necessary to implement a policy of benevolence and justice. He thinks that benevolent governance means a reduction in the use of punishment and a reduction in extortionate taxes so that the ordinary people may carry on their business in peace and calm, leaving families and society harmonious. If a state is harmonious domestically then its army, even though it be weak, will nonetheless be victorious over strong enemies. He tells King Hui of Liang, “O King, if you should implement benevolent governance for the people, reduce punishments, lighten taxes and duties, allowing for deeper plowing and ensuring that weeding is done well, then the fit will spend their holidays practicing filial piety, brotherly affection, loyalty, and constancy. At home they will serve their parents and elders; outside they will serve their masters; then they can but take wooden staves in hand and attack the armored troops of Qin [in the northwest] and Chu [in the south]. … Thus it is said, ‘the benevolent has no enemies.’”136

Xunzi thinks that the core factor of political power is the political guidelines of the state. He holds that the political line can determine the future of the government. There are three political lines to choose from—morality, strategic reliability, and political scheming—which lead to attaining humane authority, attaining hegemonic authority, and losing the state, respectively. He warns princes to choose their political line with care: “Hence in matters of state, norms being established, one can attain humane authority; reliability being established, one can attain hegemony; political scheming being established, the state will perish. These three choices are to be carefully considered by the enlightened lords, and they are something that benevolent people cannot fail to understand.”137

Mozi thinks that the core factor of political power is a policy of employing only those who are morally worthy. He thinks that the historical experience of establishing humane authority always hinges on the employment of people and whether the prince is in a favorable or difficult situation: “Under favorable conditions it is necessary to appoint the worthy. In difficult times, it is necessary to appoint the worthy. If you want to honor the way of Yao, Shun, Yü, and Tang, you cannot not appoint the worthy. Appointing the worthy is the root of governance.”138

Hanfeizi, in contrast, thinks that the core of politics is to implement a legal system: “If the one who enacts the law is strong, then the state is strong; if the one who enacts the law is weak, then the state is weak.”139 He thinks that the number of reliable, worthy people is small and inadequate to supply the needs of the state. Hence one must rely on the law to manage the officials so that they complete their tasks and undertake their responsibilities:

The number of reliable officials today does not exceed ten, but there are several hundred posts in the state. If it is necessary to employ only reliable persons, then there will not be enough for the posts available. If the posts are left unfilled, then those who do keep order will be few while the disorderly will be numerous. Hence, the way of the enlightened lord is to single-mindedly enact the law and not seek out the wise; to let techniques of governance be firm and not yearn for the reliable. Now when the law does not fail, then the various officials have no room for deceit or trickery.140

He thinks that to fail to rely on the law and to trust merely the morality of the leader is to court disaster: “By relaxing the law and techniques of governance and turning to governing by the heart, even Yao could not hold the state together on the correct path.”141 This is to say that even a virtuous prince like Yao could not have ruled a state without the use of law.

Guanzi thinks that the core factor in political power is to integrate the means of governing the state. Guanzi thinks that the morality of the leader, the employment of worthy officials, a legal system, unified thinking, and diplomatic initiatives are all related to the rise and fall of states:

A state does not fall merely because it is small or has bad luck. It is rather because the moral conduct of the lord and great ministers is not up to scratch, because official posts, a legal system, and political education are lacking in the state while externally there is plotting by the feudal lords. Because of this the territory is whittled away and the state imperiled. A state is not successful only owing to its large size or because of good luck. It is rather because the lord and his great ministers practice their virtue, because official posts, a legal system, and political education are maintained within the state and the plotting by the feudal lords without is under control. After all this, one’s efforts are crowned with success and one’s reputation established.142

Guanzi sums up all these political factors in the phrase “the techniques of doing” and goes on to say, “Those called sage kings by people in the world know the techniques of doing. … [Those] who are not esteemed by people in the world do not know the techniques of doing. For one who is capable of doing, a small [state] becomes great, a weak [state] powerful. For one who is not capable of doing, then even if he were the Son of Heaven, he could be dethroned by others.”143 He also says,

If a state’s territory is large but not well run, this situation is called being replete with land; if a state’s population is numerous but not well governed, this situation is called being replete with people; if its army is awesome but not kept in control, this situation is called being replete with troops. When the three are all replete and continue to increase, then the state is no longer one’s own state. When land is broad but not cultivated, then it is not one’s land; when ministers are honored but not subordinate as servants, then they are not one’s ministers; when the population is numerous but they are not supportive, then they are not one’s people.144