![]()

Political Hegemony in Ancient China: A Review of “Hegemony in The Stratagems of the Warring States”

The history of ancient China’s interstate politics and foreign affairs has much to say about hegemony. The Stratagems of the Warring States has much discussion of how to contend for hegemony as well as historical instances of such contention. In chapter 3, “Hegemony in The Stratagems of the Warring States,” Yan Xuetong and Huang Yuxing provide a detailed picture of the hegemonic philosophy of The Stratagems of the Warring States. Through their study the authors have summarized the foundations of hegemonic power, the role of norms in hegemony, and the basic strategy for attaining hegemony. They have also compared their findings with contemporary Western hegemonic theory and proposed that ancient China saw political power as the core of hegemony, with government by worthy and competent persons as its guarantee. They also emphasized the influence of norms on hegemony and the corresponding philosophy of contending for hegemony and hence sketched a picture of a political hegemonic theory. The present essay takes theirs as its foundation and seeks to go further in propounding the political hegemonic theory of ancient China, especially of the pre-Qin era.

ONE HEGEMONY, DIFFERENT PATHS: CONCEPTUAL LIMITS

Contemporary Western international relations theory generally defines a hegemonic state in terms of material strengths such as its capacity to make war, its military power, or its economic power. A hegemonic state may be called the dominant power, the predominant or preeminent power, or the leading power or be said to have leadership or world leadership. John Mearsheimer writes, “A hegemon is a state that is so powerful that it dominates all the other states in the system. No other state has the military wherewithal to put up a serious fight against it.”1 Robert Pahre sees the basic indicator of a hegemony in the state’s share of world resources and its GNP relative to the rest of the world.2 Joshua S. Goldstein thinks that a hegemonic state is one that has the greatest military, economic, and political strength.3 Robert T. Gilpin believes that a hegemonic state is a state that controls or dominates the lesser states in the international system.4 Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye think that a hegemonic state refers to “one state [that] is powerful enough to maintain the essential rules governing interstate relations, and [is] willing to do so. In addition to its role in maintaining a regime, such a state can abrogate existing rules, prevent the adoption of rules that it opposes, or play the dominant role in constructing new rules.”5 They point out that in a time of globalization and interdependence, military power plays a minor role.6 The importance of the economy far exceeds that of the military. Immanuel Wallerstein argues that hegemony in the interstate system refers to “that situation in which the ongoing rivalry between the so-called great powers is so unbalanced that one power is truly primus inter pares; that is, one power can largely impose its rules and its wishes (at the very least by effective veto power) in the economic, political, military, diplomatic and even cultural arenas.”7

The conceptions of the hegemonic state in ancient Chinese thought and in Western international relations theory are very similar. In ancient Chinese, “hegemon” (ba) and “lord” (bo, father’s elder brother, a senior peerage) both refer to “the head of the feudal lords in ancient times.”8 In other words, a hegemonic state holds the highest status among the feudal states and is ranked the first state. In this sense, ancient China’s hegemony and Wallerstein’s “primus inter pares” are the same. In the pre-Qin classics, a hegemonic state is generally referred to directly as “hegemon,” but often this term is interchangeable with “great state.” This is the same as in Western international relations theory. Both hold that a hegemonic state is first a great state or a kind of great state. Ancient China customarily calls a hegemonic state a “lord of the hegemony,” as “in the Spring and Autumn Period, the greatest power attained the leading role among the feudal lords.”9 This way of thinking is very similar to that of Mearsheimer.

Since ancient times, however, the Chinese word for hegemonic power and its related concepts have undergone a major shift in meaning. In the Western Zhou, “five states formed a community and the community had a leader. Ten states formed a union and the union had a general. Thirty states formed an army and the army had a ruler. 210 states formed a continent and a continent had a lord.”10 As the “head of the feudal states,” being a hegemonic state was a symbol of status and honor. The status of hegemon came from a feudal gift of the kingdom. After the Spring and Autumn Period, “the Son of Heaven declined while the feudal lords emerged, and thus they are called ‘hegemons.’ A ‘hegemon’ (ba) ‘grasps hold of’ (ba), which refers to his grasping hold of the political education of the sage king.”11 This means that a state that relied on powerful force and managed to win hegemony was called a hegemon. Although the substance was the same as in the past, the origin was different, and thus the word hegemon replaced that of lord. Mencius was the first to understand the way of the hegemon and the way of the sage king as two different political routes, thus giving rise to “the conflict between sage kings and hegemons.”12 In contemporary Chinese, the term lord of the hegemony refers to “the person or group with the most prestige and power in a given field or geographical area,” while hegemon, hegemonism, and a hegemonic state begin to be associated with words with negative connotations, such as arbitrary, control, oppress, and invade.13 The notions of “hegemony” and “hegemonic state” used in chapter 3 and here follow the meaning of the terms in ancient Chinese, which reads them as neutral terms. It is only here that the hegemonic philosophy of ancient China can be compared to that of contemporary Western hegemonic theory.

THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF POLITICAL HEGEMONY

Hegemony is the result of competition for comprehensive state power, but the place of different factors of power in a hegemony may differ. Western hegemonic theory in general distinguishes four theories of core factors of power. (1) Geopolitical theory: Alfred T. Mahan thinks that sea power is the core factor in world hegemony.14 Halford J. Mackinder thinks that land power is the core factor. He constructed a famous syllogism of world hegemony: “whoever controls eastern Europe controls the heartland; whoever controls the heartland controls the world-island; whoever controls the world-island controls the world.”15 Giulio Douhet developed a theory of airpower and stressed that command of the air plays a core role in establishing world hegemony.16 (2) Military hegemonic theory: Mearsheimer thinks that military power—especially that of the army and the capacity for war that it embodies—is the core factor of hegemony.17 (3) Economic hegemonic theory: Wallerstein, and Keohane and Joseph Nye maintain that economic power and status in the international economy are the core factors in hegemony.18 (4) Military-economic hegemonic theory: Paul Kennedy says that the interaction of wealth and power or of economic and military strength is the core factor in world hegemony.19

The Stratagems of the Warring States describes discussions among various schools of thought in interstate politics and foreign affairs during the Warring States Period. In this way it has preserved what the different schools thought about hegemony in pre-Qin times. Like Western hegemonic theorists, “the strategists of The Stratagems of the Warring States analyze the components of comprehensive national power. Moreover, the factors of national power they analyze are of different kinds. Unlike some scholars today, they do not see comprehensive national power as composed only of economic aspects. Among the factors of national power, they frequently mention four: political, military, economic, and geographic.” Unlike Western hegemonic theory, in ancient Chinese hegemonic philosophy there is a school that puts political power as the core factor of hegemony and from this constructs the foundation for a theory of political hegemony.

The theory of political hegemony holds that the core factor of hegemony is political power, and the heart of political power is the ability of the government to govern the state and its influence. According to the summary in chapter 3, the hegemonic theory in The Stratagems of the Warring States holds that “political power is the core of hegemonic power.” Moreover, in the discussion of military power and geographical factors as against political power, it stresses the importance of political power: “Rely on politics; do not rely on courage.”20 Yan and Huang go on to point out that “the merits and leadership of the ruler and the chief ministers are frequently seen as the core factors in hegemonic political power.” Political power is expressed mainly in two aspects: the first is the leadership, or, better, the ability to govern, of the government; the second is the virtue and self-cultivation of the important officials in the government and the political influence that flows from this.

The theory of political hegemony holds that the government’s ability to govern, especially that of the ruler and important ministers, determines the fate of the hegemony. Mozi points out, “Huan of Qi was influenced by Guan Zhong and Bao Shu; Wen of Jin was influenced by Jiu Fan and Gao Yan; Zhuang of Chu was influenced by Sun Shu and Shen Yi; Helü of Wu was influenced by Wu Yuan and Wen Yi; Goujian of Yue was influenced by Fan Li and Minister Zhong. What these five princes were influenced by was correct, and so they held hegemony over the feudal lords. Their deeds and fame was passed down to later generations.”21 When Bao Shuya recommends Guan Zhong as prime minister, he says, “You, O Prince, wish to be a hegemonic king; without Guan Yiwu, it is not possible.”22 After Guan Zhong had become the prime minister of Qi, he did indeed help Qi to establish hegemony. Confucius also acknowledged that “Guan Zhong served Duke Huan, who was hegemon over the feudal lords.”23 And, “Duke Huan gathered the feudal lords from the nine directions not by troops and chariots but by the strength of Guan Zhong.”24 On the contrary, the economic and military power of Qin were both the best, yet the reason Qin was unable to be hegemon was in part because of “the clumsiness of its ministers in charge of planning.”25 Therefore, the theory of political hegemony proposes “worthy princes and enlightened prime ministers,” and firmly believes that “when the worthy person is present, then all under heaven submits; and in the use of one person, all under heaven will obey.”26

Political hegemony stresses that moral influence is of capital importance. Moral influence comes from the merit and self-cultivation of the ruler and his important chief ministers and the policies that derive from this. Virtuous conduct is the basic requirement of the lord of the covenants, or rather of the hegemonic lord: “A great state determines by justice and thereby becomes the lord of the covenants.”27 And, “Without virtue how can one be lord of the covenants?”28 Duke Huan of Qi “relieved poverty, and paid the worthy and capable”29 and undertook to “examine our borders, return seized territory; correct the border marks” and to “not accept their money or wealth.”30 In this way he secured the hegemony for Qi. Duke Wen of Jin “revised his administration and spread grace on the ordinary people”31 and in this way realized the hegemony for Jin. Qin had a wealthy state and a strong army but, because the virtue of Duke Mu of Qin was inferior, in Qin “laws and commands were constantly issued.” “Laws were severe and lacking in mercy, only relying on coercion to keep people submissive.”32 Therefore, “it is fitting that Mu of Qin did not become lord of the covenants.”33 Political hegemony holds that fidelity is the most important constituent component of moral influence: “fidelity so as to implement justice; justice so as to implement decrees.”34 Xunzi notes, “Huan of Qi, Wen of Jin, Zhuang of Chu, Helü of Wu, and Goujian of Yue all had states that were on the margins, yet they overawed all under heaven and their strength overpowered the central states. There was no other reason for this but that they had strategic reliability. This is to attain hegemony by establishing strategic reliability.”35

The theory of political hegemony does not exclude the necessity of material power. The international political philosophy of ancient China held that power that was material in nature and influence that was moral in nature were two basic aspects that constituted power: “The means by which Jin became a hegemon was the military tactics of its generals and the strength of its ministers.”36 Also Mencius says, “Using force and pretending to benevolence is the hegemon. The hegemon will certainly have a large state.”37 Hence, “for a state to maintain its hegemonic status, equal emphasis must be given to virtue, awe, and fidelity.”38

The formation of political influence is a hierarchical process. Ancient China’s international political philosophy and contemporary Western international relations theory both stress the use of hierarchical analysis to observe and analyze the world, and construct a theory of world politics. The difference between them is that in ancient China’s international political philosophy there were four levels of analysis: the individual, the household, the state and the world. Among these four levels there exists a hierarchy and a relationship of cause and effect; thus

Cultivate yourself, manage your family, administer the state, and bring peace to all under heaven.

Of old those who wished to make their bright virtue shine in all under heaven first administered their state. Those who wished to administer their state first managed their family. Those who wished to manage their family first cultivated their person.

Or again, “When you have cultivated yourself, then manage your family; when your family is managed, then administer the state; when the state is administered, then all under heaven is at peace.”39 Different levels of material power and their corresponding levels of morality determine the levels of power in the international political system. In the Spring and Autumn Period, after Qi had attained hegemony, Duke Huan of Qi hoped to go one step further and develop to the level of humane authority. Hence he says to Guan Zhong, “I wanted to be a hegemon and, thanks to the efforts of you and your companions, I have become a hegemon. Now I want to be sage king. It is possible.” Guan Zhong and his fellow ministers tactfully tell the duke that since his virtue has not yet reached the level of a sage king, Qi could not realize humane authority. Duke Huan therefore renounces pursuit of humane authority and remains content with hegemony.40

From this it can be seen that in the sequence of factors leading to hegemony, the greatest difference between China and the West lies in the degree of emphasis given to moral influence and its role. Western geopolitical theory, while emphasizing the geographical environment as the core factor in world hegemony, also holds that even though political power is a constituent part of comprehensive state power or geopolitical power, yet the importance of political power falls far short of that of the geographical environment. Military hegemonic theory, economic hegemonic theory, and military-economic hegemonic theory all follow the same line. Ancient China’s hegemonic thought believes, however, that political power, with moral influence as its core, is an indispensable constituent of power. At the same time, it is present at each level of power, always as the preeminent element. But, generally speaking, hegemony tends toward a greater demand for material power, whereas humane authority sets a relatively higher standard for moral influence. Furthermore, the difference between hegemonic theory in China and in the West lies in a different understanding of the relationship of cause and effect among the different levels. Whereas both China and the West use hierarchical analysis, Western hegemonic theory tends to emphasize the influential role of the priority and structure of the international system of comparative power on hegemony: it is a case of a relationship of cause and effect that moves from the outside to the inside. Ancient China’s hegemonic thought puts more emphasis on the deciding role hegemony plays in the international system: it is a case of a relationship of cause and effect that moves from the inside to the outside.

POLITICAL HEGEMONY IN THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM

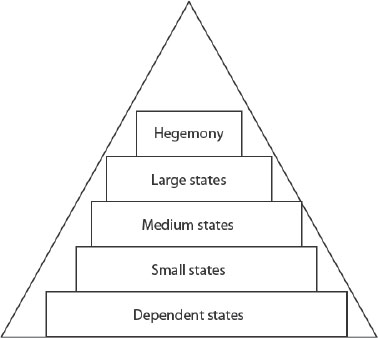

In Western hegemonic theory, hegemony is situated at the pinnacle of the structure of internal political power. It is the highest possible form of international power. In the structure of international political power, according to the size of their power, states form a pyramidal hierarchy (see figure 6.1). Depending on the number of hegemonies involved, Western international relations theory defines the international system as one of unipolarity, bipolarity, or multipolarity.

In ancient China’s hegemonic philosophy, hegemony is not the highest form of power in the system. The Guanzi distinguishes four levels of state power from top to bottom: sovereignty, empire, humane authority, and hegemony.41 The main distinction that the Xunzi makes is between humane authority and hegemony.42 Sovereignty and empire are both forms of state power that belong to the times of ancient Chinese myths and legends, or rather, they belong to an ideal level of power that cannot be realized in the real world. (The united kingdoms founded from the Qin onward all believed that the world they knew was the entire world and thought that the empires they founded did realize the goal of sovereignty or empire.) Hence, the ancient Chinese classics, including The Stratagems of the Warring states, all acknowledge that the main distinction in power is between humane authority and hegemony. Humane authority refers to the unity of all under of all under heaven or, rather, to the formation of a united stare ruling over all the then-known world. It is the first level of power in the real world of politics. Hegemony refer to a power that can influence or even control other stares within a fragmented world, and it is the second level of power, below that of humane authority. In other words, there is “distinction of top and bottom” between humane authority and hegemony.43

Figure 6.1 The pyramid of power envisioned in Western international relations theory.

Hence, in contemporary Western international relations theory, hegemony has become the main strategic goal for a state even its ultimate goal: “The overriding goal of each state is to maximize its share of world power, which means gaining power at the expense of other states, But great power in the system.”44 But in ancient China’s international political philosophy, hegemony is not the ultimate goal for a state. In chapter 3, Yan and Huage fail to distinguish between hegemony and humane authority in The Stratagems of the Warring States and also fail to distinguish between the shift in strategic goals between the early and late Warring States Period. In the early Warring States Period, hegemony was the core of the struggle between the states, but at the end of the period, the strategic goal of Qin was not satisfied with hegemony but aspired to humane authority.

Hegemony is very closely linked to stability or lack thereof in the international system. In Western international relations theory, the theory of hegemonic stability emphasizes the causal relationship between hegemony and the stability of the international system. Neoliberalism, however, emphasizes the causal relationship between the rise and fall of a hegemon as well as shifts in hegemony and shifts in the system. Charles P. Kindleberger points out that what enables the world economy to be stable invariably comes from the stabilizing role of a given state and only one state can perform this function.45 Robert O. Keohane says that a hegemon determines norms and then encourages other members to follow them and in this way promotes international cooperation.46 The theory of long cycles of hegemony thinks that the rise and fall of hegemonies brings about shifts in hegemony. Shifts in hegemony both give rise to wars in the system and, as a result of these wars, bring about the exchange of hegemonic power and thus lead to changes in the system.47

Ancient Chinese hegemonic philosophy also concentrates on the relationship between hegemony and international norms as well as the international system. Yan and Huang summarize The Stratagems of the Warring States on this point: “the relationship of norms to the legitimacy of hegemony, the relationship between respecting norms and using military force, and the relationship between the establishment of new norms and the preservation of old norms.” According to this summary, the hegemonic philosophy of The Stratagems of the Warring States holds that norms provide the basis for the legitimacy of a hegemon and are a support for a hegemon’s use of military force. The establishment of norms is necessary for a hegemon but it also carries a grave risk. Whether the new norms win international approval directly determines the hegemon’s legitimacy. All states may aspire to be called hegemonies: “Duke Wen for this reason made his officials of different ranks and formed the laws of Beilu and so became the lord of the covenants.”48

Hegemony is founded through a series of international norms and brings it about that the international organizations that take these norms as their center embody the hegemon’s power. Likewise, international norms and international institutions will also be internalized as a constituent part of hegemony, giving rise to institutionalized hegemony. Therefore, Robert W. Cox indicates that there are three factors in hegemony: “a configuration of material power, the prevalent collective image of world order (including certain norms), and a set of institutions which administer the world order with a certain semblance of universality.”49 Ancient China’s hegemonic philosophy concentrates on respecting the past, even the international norms and mechanisms left by the ancient kingdoms, and is wary of determining new norms. Political hegemonic theory holds that respect for, and even restoration of, the old international norms and mechanisms of the kingdoms is an important part of moral influence. Furthermore, if one wants to respect and uphold or restore old norms and mechanisms, then it is necessary to create new norms and mechanisms directed by a hegemony. But the establishment of new norms and mechanisms so as to restore and uphold or respect old existing norms and mechanisms at the same time whittles away at the old existing norms. Hence, political hegemonic theory falls into a dilemma.

POLITICAL HEGEMONY AND ITS FOREIGN STRATEGY

Political hegemonic theory results in a strategy of working with allies. Xunzi says, “one who befriends the feudal lords becomes a hegemon.”50 Political hegemonic theory holds that the basic indication of the firmness of hegemony is whether political influence can ultimately gain international recognition, and international recognition of a hegemony is decided by three factors: first, the establishment of alliances of friendship with most of the states within the system; second, becoming allies with the main large states in the system; and third, being able to preside at the meeting of the allies, that is, to become the lord of the covenants. “In the Spring and Autumn Period, great states used their allies to contend for hegemony and took ascendancy to the position of lord of the covenants as the standard for calling themselves a hegemon.”51 Yan and Huang go further in pointing out: “If this bloc is the strongest bloc within the world system, then the head of the bloc is the biggest hegemonic power. If that state heads the only bloc, then it is the only hegemonic power within the system.” Hence, political hegemonic theory holds that to become a hegemon one must first become the lord of the covenants. “A covenant meeting can determine the public recognition of the status of a hegemon.”52 “Speaking from the history of the Spring and Autumn Period, there was no feudal lord who attained to hegemony without successfully realizing the strategy of managing a covenant meeting.”53 In the Spring and Autumn Annals and Zuo’s Commentary alone there are 246 instances of covenant meetings.54 After Duke Huan of Qi presided at a covenant meeting in Juan, “Qi began to be a hegemon.”55 At the peak of Qi’s hegemony, during the forty-three years of Duke Huan’s rule in Qi there were thirty-nine covenant meetings, of which the duke personally took part in twenty-one.56 Duke Wen of Jin presided in succession at the meetings at Jiantu and Zhequan and “began to be hegemon over all the feudal lords.”57 Wu called a meeting for a covenant at the Yellow Pool and “was hegemon over the central states.”58 Thanks to the covenant meeting at Xuzhou, Yue “was termed hegemonic lord.”59 Meanwhile, though Qin had a rich state and a strong army and cleared a thousand square li of land, because it was not able to call together the states and preside over a covenant meeting it could only “be a hegemon over the Western nomadic tribes.”60 In the early Spring and Autumn Period, “when there was no hegemonic lord,”61 Zheng was the most powerful and the strongest state but it could be called only a “little hegemon.” “The main reason for this was because it had not yet been able to establish itself as such during the covenant meetings of the feudal lords.”62

Political hegemonic theory holds that besides affirming hegemony, covenant meetings have two additional important political functions: the first is to control the allies and prevent them from falling away from the alliance, and the second is to determine international norms such that the will of the hegemonic state becomes the international consensus and thus institutionalizes the hegemony. The covenant meetings of the Spring and Autumn Period naturally put more emphasis on multilateral foreign relations, whereas those of the Warring States Period tended to stress bilateral foreign relations. Hence, “toward the end of the Spring and Autumn and in the early Warring States Period, the custom of covenant meetings went into decline. In the mid to late Warring States Period, the meetings evolved into vertical or horizontal alliances.”63 During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, the strategy of holding covenant meetings was not only to establish bonds with allies and uphold the alliances but also to undermine opposing alliances. The frequency with which alliances were concluded between states during the Warring States Period was very great. They were also ideas on how to undermine the alliances of one’s opponents. Therefore, in general during the pre-Qin period the strategy of winning allies was a matter of expediency and there was no strategic value accorded to maintaining an alliance.

Political hegemonic theory is not opposed to sending punitive expeditions abroad but it prefers the military strategy of acting in response to aggression. In contrast to humane authority, which looks more to the attractive force of moral influence to gain the willing submission of other states, political hegemonic theory tends to look to military action to gain submission from other states. Political hegemonic theory is also different from the expansionism of great power politics, however, since it prefers to use the military in response to aggression. Responding to aggression comprises two aspects. On the one hand, it indicates that when foreign relations strategies fail there is no option but to use military means. On the other hand, it means that only after one’s opponent has resorted to force will one adopt military action in response. At its greatest extent, the strategy of responding to aggression is a necessary means by which hegemony can gain moral influence: “If you can stop troops and only later respond, give a hand to others to punish what is not correct, conceal your desire to use troops and rely on justice, then it is to be expected that you can reign over all under heaven by standing on only one foot.” Hence, “If they truly want to make their will that of becoming lord and sage king, then they must not first engage in war or aggression.”64 In the process of winning submission from abroad, political hegemonic theory holds that it is more important to win over people than territory. Control over territory is just a part of gaining submission and it may lead to one’s opponent developing nationalism and hopes for national restoration such that they become your most dangerous enemy. It is only by means of moral influence that one can win over the people’s minds and thus accomplish a through submission. Therefore, political hegemonic theory is opposed to making profit one’s motive or to the selfish and self-serving extension of power and bloody seizing of territory and invasion.

Political hegemonic theory stresses international duties and responsibilities. Political hegemonic theory holds that international norms must win the respect of the whole body of the nation, especially requiring that the hegemonic state itself should be the first to respect the rules and in that way it can lead other states to respect them as well. As for states that turn their backs on the norms recognized by the international community, a hegemonic state has the power and duty to punish them: “being the lord of the covenants, one may punish those who reject the decrees.”65 In the Spring and Autumn Period, international norms were expressed largely by upholding the ritual order of the Zhou court; hence the hegemon led the way in respecting the Zhou rites and had the duty to uphold the same rites: “Without ritual, how can we preside over covenants?”66 A hegemonic state has the duty of providing security guarantees to small and medium states and in times of danger, such as famine, of providing economic assistance: “to be compassionate in great matters and overlook the small makes one fit to become lord of the covenants.”67 In the Spring and Autumn Period, the duties of the lord of the covenants included “loving your friends, being friendly with the great, rewarding your allies, and punishing those who oppose you.”68 Political hegemony holds that a hegemonic state enforces its international duty by strengthening its moral influence, and only a ruler and chief ministers of a certain merit can undertake this. Thus it is said, “The lord of the covenants has a definite duty and should have the standing that matches up to this.”69

CONCLUSION

Ancient China’s theory of political hegemony is different from the Western theories of military hegemony, economic hegemony, and military-economic hegemony. The factor of political power replaces the military, economic, and military-economic power found in the Western theories and becomes the core element of hegemony. Political hegemonic theory holds that while a rich state and a strong army are important elements in the constitution of hegemonic power, their importance is not as great as that of political power. The heart of political power is the ability of the government to govern and its moral influence. The way in which the government’s ability to govern is displayed lies in the administrative ability and moral cultivation of the head of the government and his main officials, whereas moral influence is shown in the capacity of the success of the state’s political and economic model to attract other states. Political hegemonic theory holds that hegemony is not the highest level of power in interstate politics.

Political hegemonic theory holds that there is a close connection between the domestic and international levels. The domestic determines the role of the international. Hence, political hegemonic theory advocates using a new model of political system to develop the economy by establishing a highly effective governing team to promote the development of the state’s economic and military power. Political hegemonic theory gives priority to domestic government and advocates first managing one’s own affairs well rather than directly challenging the status of the current hegemonic state. Political hegemonic theory holds that moral principles are an indispensable part of hegemony. In domestic politics, the quality and merit of the highest government leaders should be raised, whereas in the international sphere one has the duty to promote the maintenance of international norms and accept the responsibility of providing security guarantees to small and medium states and giving them economic assistance. Political hegemonic theory is a new, nonconfrontational model for the rise of a state.