Creating Customer Delight

What do the Rubik’s Cube, the cholesterol drug Lipitor, the Switch game console, Super Mario Bros., the Toyota Corolla, and Lady Gaga’s Fame perfume have in common? They are all products that flew off the shelves as soon as they were launched. The Rubik’s Cube sold 2 million units in the first two years. Nintendo’s Switch racked up 1.3 million unit sales in a single week. In each of their respective categories, these are among the most successful product launches of all time.

A common thread to these products and services is that their creators found ways to significantly increase customer willingness-to-pay (WTP). Lipitor, one of the bestselling prescription drugs of all time, was not the first statin that lowered LDL, the “bad cholesterol,” but it was far more effective than its rivals. Bruce D. Roth, Lipitor’s inventor, explains, “[Lipitor] tremendously, incredibly outperformed the other statins. It was as good at its lowest dose as the other statins were at their highest.”1 Similarly, Shigeru Miyamoto, the Nintendo designer who introduced the world to Super Mario Bros., found ways to transform the experience of playing video games. Miyamoto, not a programmer himself, was already famous when he created Super Mario Bros., but with the new game, he hit it out of the park.2 The Economist gushed, “The game took place under a clear blue sky at a time when most games were played on a space-y black background. Mario ate magic mushrooms that made him bigger, or ‘super,’ and jaunted from place to place through green pipes. ‘Super Mario Bros.’ offered an entire world to explore, replete with mushroom traitors (‘Goombas’), turtle soldiers (‘Koopa Troopas’) and man-eating flora (‘Piranha Plants’). It was full of hidden tricks and levels. It was like nothing anybody had ever seen.”3

As these examples illustrate, there are innumerable ways to raise the WTP for products and services. Think of WTP as a wide-open construct. It is influenced by the utility of products, the pleasures they evoke, the status they confer, the joy they bring, and even by social considerations that have little to do with the characteristics of the products themselves. Lady Gaga’s perfume Fame was novel, for sure—a black liquid that sprays clear—but it is safe to assume that part of its success was the association with the artist, the promise, as Gaga put it, that wearing her perfume would give customers “a sense of having me on your skin.”4 (This, by the way, also goes to show how radically WTP varies from person to person; wearing Gaga on your skin, definitely not everybody’s idea of a desirable sensation.)

Of course, these descriptions of ways to increase WTP tell you nothing that you do not already know. It is common sense to develop products and services that meet the needs of customers. In fact, I don’t know of any company that does not claim to serve customer needs, to be customer centric. So what’s new? Isn’t aspiring to raise WTP and customer delight the same as thinking about fabulous products and services?

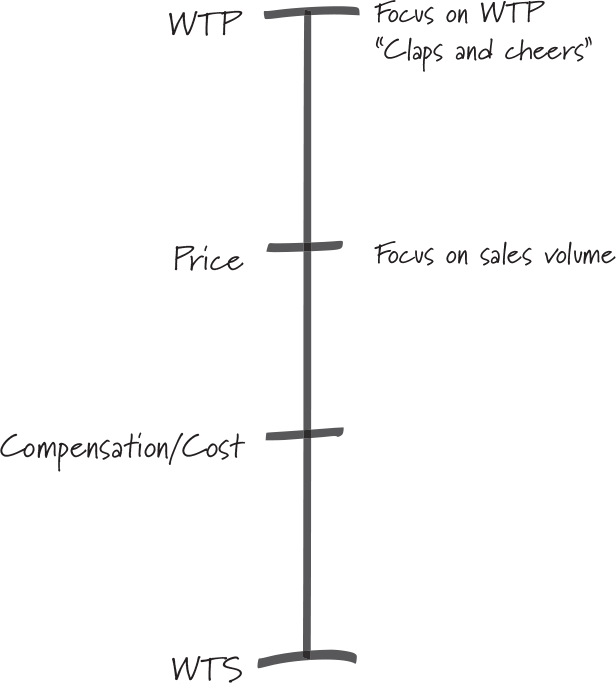

The distinction between focusing on product and focusing on WTP is subtle—but important. A product-centric manager asks, “How can I sell more?” A person concerned with WTP wants to see her customers clap and cheer. She will seek ways to improve customers’ experience even after they have committed to a purchase (figure 4-1). A product-centric manager deeply understands purchase decisions and is interested in ways to sway the customer. Managers who pay attention to WTP consider the entire customer journey and search for opportunities to create value at every step along the way.

Figure 4-1 Many companies pay more attention to sales than customer WTP

A few years ago, I had an interaction with a salesperson that illustrates the difference. I meant to send flowers to a friend for her birthday. Her day came and went, and somehow I forgot. A few days later, I remembered and called a shop to order flowers. It was late afternoon, and the salesperson asked whether I wanted to have the flowers delivered that day or the next. I confessed to being late for my friend’s birthday and urged the salesperson to send the flowers as quickly as possible. Her response caught me by surprise: “Should we take the blame for the late delivery?” I didn’t want her to lie for me, of course. But even in that brief conversation, I saw that this salesperson did not see her job as simply selling flowers; she did not suffer from a narrow product-centric mindset. Her job was to increase her customers’ WTP. (The story has a perfectly predictable ending, by the way. I now receive a reminder a few days ahead of my friend’s birthday, and I order my flowers, perhaps at inflated prices. But I have never even considered using another flower shop.)

Companies that focus on WTP enjoy a long-term competitive advantage for several reasons. One is that we trust companies that have our best interests at heart. In addition, these organizations are often better at identifying opportunities for value creation. They also tend to be more skillful at recognizing the needs of multiple groups of customers and intermediaries, paying attention to instances where raising the WTP for one group lowers the WTP for others. Finally, companies that raise WTP substantially benefit from customer selection effects. Let me illustrate each of these factors with an example.

Customers’ Best Interests

John C. Bogle founded the Vanguard Group, today one of the world’s largest investment companies, after he was fired “with enthusiasm” from his first position at Wellington Management Company. In an industry riddled with conflicts of interest—one recent US government estimate put the cost of deceptive advice from commission-hungry broker-dealers at $17 billion annually—Bogle (and Vanguard) became known as the “mutual fund investor’s best friend.”5 “Our challenge at the time,” he recalled, “was to build … a new and better way of running a mutual fund … and to do so in a manner that would directly benefit [our clients].”6 Under his leadership, the company introduced no-load funds, and it brought low-cost index investing to the individual investor, long before passive investing became fashionable. First ridiculed as “un-American” and “a sure path to mediocrity,” passive funds now account for almost 45 percent of all equity assets in US mutual funds and exchange-traded products.7

Throughout his career, the outspoken Bogle criticized his industry for high prices, misleading advertising practices, and product proliferation that creates little value for investors. In his 2010 book Enough: True Measures of Money, Business, and Life, he summarized Vanguard’s goal and his own personal aspiration: “What I’m battling for—[giving] our citizen/investors a fair shake—is right. Mathematically right. Philosophically right. Ethically right.” For Bogle, clients’ WTP and customer delight always came first. It was this principle that enabled him to build one of the most successful and widely admired companies in a fiercely competitive industry. His clients always knew that Bogle had their best interests at heart.

Identifying Novel Opportunities

E-readers were the hot consumer electronics product of the late 2000s. Only a decade after they were introduced in 2004, one-third of Americans owned one.8 A billion-dollar market had been born. Sony, the leading consumer electronics company at the time, was first to offer an e-reader, the Librie, and it was Sony that set the industry standard by adopting electronic ink, microcapsules that contain dark and white pigments that can each be stimulated to flow to the top and display one or the other color. The Librie offered an unparalleled reading experience on an electronic device.9

Amazon was keen to enter this fast-growing market, but its prospects seemed limited. Sony had adopted the leading technology, was first to market, and spent twice as much on marketing as its rivals.10 Despite these advantages, Amazon beat Sony handily. By 2012, Amazon’s Kindle, introduced in 2007, commanded a 62 percent market share. Sony’s e-reader stood at a measly 2 percent.11 What made the difference? Wireless access. Sony customers had to download books to their PCs (from a hard-to-navigate store with a limited selection of titles) and then transfer their purchase to the reader. When Sony upgraded its device to make PDF and ePub documents accessible, customers had to send their readers to Sony service centers to update the firmware.12 By contrast, Amazon’s Kindle offered free 3G internet access, a feature that turned books into an impulse purchase. When it was first launched, the Kindle sold out in five hours.13

Product-centric companies like Sony pay close attention to the quality of their devices. Sony created a wonderful reading experience, which it knew was an important factor in a customer’s decision to buy the novel device. Amazon, by contrast, focused on WTP. With that broader notion, it offered convenience throughout the customer journey. By the time Sony got around to introducing wireless, it was too late. The market had tipped in Amazon’s favor.

Once you start thinking in terms of WTP, new opportunities to create customer delight arise all the time, and all kinds of “obvious” decisions become a little less evident. For example, where would you install ticket vending machines in a subway? In front of the turnstile entrance, or on the platform? The question seems like a no-brainer. The machine cannot be on the platform; customers need to purchase their tickets before they go through the turnstiles. Correct! And yet, you might wonder if we would create a better customer experience if we placed machines in both places. If you watch customers waiting in line to buy a ticket or top up their subway cards today, you will see frantic activity, riders frustrated by long lines, all of them desperately trying to get their ticket as quickly as possible so as not to miss their train. Once they are on the platform, these same customers then wait patiently for the next train to arrive. How much value would we add by placing a vending machine on the platform? Would customers appreciate the opportunity to use their wait time more productively? Could we, in fact, increase WTP by allowing riders to top up their subway cards in a more leisurely fashion? Before you know it, the “obvious” placement of vending machines is a little less evident. Paying close attention to WTP throughout the customer journey allows you to see opportunities for increasing customer delight in a myriad of ways. Motivating consumers to purchase a product and facilitating its sale (by placing vending machines before the turnstiles) is a far narrower concern than the ambition to create a great customer experience.

Recognizing the Needs of Customers and Intermediaries

Bigbelly produces solar-powered trash bins (figure 4-2).14 The bins compact trash automatically, and they alert sanitation staff when the compactors need to be emptied. The company estimates that trash collection efforts using these bins can be reduced by as much as 80 percent, saving staff time and travel cost for the sanitation department. The bins also promise an end to overflowing trash cans. When Bigbelly entered the market in 2003, cities everywhere were eager to sign on. The city of Philadelphia alone ordered close to 1,000 units.

Figure 4-2 Bigbelly trash compactors—original model

Once installed, however, the bins quickly revealed a near-fatal flaw. Online reviews were scathing, even by the standards of today’s foul-mouthed internet. One (polite) user remarked, “[The Bigbelly compactors] quickly became even more disgusting than regular trash cans.… You actually have to touch a handle to open the slot. Just think of all the germs passed from person to person on that grimy handle. *shudder* I can’t think of a more unsanitary design for an outdoor trash can.”15 Another said, “[My wife] will only open the trash can if she has a napkin or a paper sack handy so that she never actually touches the handle with her skin.… I noticed that a lot of other people do the same. Sometimes people put trash on top of the container, presumably because they don’t want to touch it. I don’t really blame them, either: some of the trash cans look pretty grimy these days.”16

Bigbelly had produced a near-perfect solution for one group of customers, the sanitation departments, but it paid little mind to a second group, the people who actually use the bins. Seeing the negative reactions to the compactors, the city of Philadelphia asked the company to replace one-quarter of its bins free of charge and develop an improved design.17 Fortunately, Bigbelly found a simple but effective solution: it added foot pedals to the bins, re-creating the hands-free experience that people appreciate in traditional trash cans (figure 4-3).18

Figure 4-3 Bigbelly trash compactors—new model with foot pedal

It is natural to think of your company’s customers as the organizations and individuals who pay you. Bigbelly therefore focused on sanitation departments in the same way that insurance companies pay attention to brokers and consumer product organizations work closely with supermarkets. In each case, the final customer is one step removed. For a company whose sole focus is on sales and on the entity that pays the bills, it is all too easy to neglect the customer it ultimately serves. By contrast, organizations that rely on a broader yardstick—the WTP of the intermediary and the final customer—are often at a competitive advantage.

In fact, if managers universally focused on WTP, I would not have the following story to tell you. In 1997, two bright but inexperienced graduate students visited the offices of Excite, a company that had built a popular internet search engine.19 The students met with Excite’s CEO, George Bell, hoping to sell their engine, an obscure piece of software they called Backrub, for $1.6 million. To demonstrate Backrub’s superiority, they searched the term internet on both engines. Excite prominently displayed Chinese web pages on which the word internet stood out. Backrub, on the other hand, provided precisely the kinds of links that users might be interested in.

How excited was Bell? Not at all. In his view, Backrub was too good! You see, Excite’s business model was advertising. For its purposes, the longer users spent on Excite’s site, and the more often they returned, the more money the company would make. In Bell’s world, it was a terrible idea to quickly send users elsewhere by providing highly relevant search results. To optimize revenue, Bell explained, he wanted Excite’s engine to be 80 percent as good as other engines. The Backrub deal never took place. You guessed it, of course. Those two students were Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the founders of Google. Imagine you had bought Google, now valued at more than $1 trillion, for a pittance.

Business models describe how companies capture value. Without value creation, however, the question of how you capture value is moot. Even worse, an obsession with business models can easily undermine value creation, as the Google story illustrates. From the 20th-century Phoebus cartel, which purposely limited the life of incandescent light bulbs, to today’s ink cartridges whose smart chips disable printing in any color when only one of the colors falls below a certain level, history provides countless examples of firms that strengthen their ability to capture value at the expense of creating it. Is it wrong to take solace in the fact that history is generally unkind to firms that pursue these kinds of strategies? Does anyone remember Excite?

Benefiting from Customer Selection Effects

Companies that focus on WTP also perform better because they get to serve the “right” customers. Depending on how your company raises WTP, specific groups will find your product extra appealing. Consider Discovery, a South African life and health insurance company whose ambition is to improve the health of its customers.20 Its trademark Vitality program provides preferential access to fitness clubs; wearables allow customers to earn Vitality points by tracking their exercise; and Discovery even partners with grocery stores to offer its members healthier food. With millions of members, Discovery bills itself as “the world’s largest platform for behavioral change.” Founder and CEO Adrian Gore explains, “The beauty of it is the shared value it creates.… Our customers are given an incentive to become healthier … and we are able to operate with better actuarial dynamics and profitability.”21 Selection effects are critical for Discovery’s success. The company increases the WTP for individuals who are health conscious. With a substantial advantage in WTP, you get to serve (often at a lower cost) the very customers for whom your value proposition is particularly attractive.

WTP as Your North Star

The difference between a product-centric mindset that is motivated mostly by sales and a mindset that focuses on WTP may seem like a fine distinction at first. The stories of Vanguard, the Kindle, Bigbelly, and Discovery show, however, how seeing the world through the lens of customer WTP can confer significant advantage.

Taking value creation seriously can have dramatic strategic consequences. Kaspi.kz, Kazakhstan’s leading fintech company, abandoned its thriving credit card business because it was unable to see a way to create significant value for its customers. Chairman Mikhail Lomtadze explains, “I was giving management presentations saying how many months it takes us to make $100 million—initially, it was 18 months, but it quickly became 12 months and then 6 months. This was our metric. I was really pushing the idea [of] being efficient and profitable … but we ended up where most financial services end up: with customers just hating us.”22 Kaspi turned from credit cards to the seemingly humdrum business of bill payments, a serious pain point in the Kazakh economy. “There is this famous story about a university in Russia,” says Lomtadze. “First, they built the buildings. But instead of paving the roads on campus, they allowed people to find their own way. Once the trails were formed, they laid the concrete. This is how we think about our process.” With a beloved bill payment service at its core, Goldman Sachs–backed Kaspi went on to build an ecosystem of products that is now valued in the billions of dollars. Having learned the difference between value created and value captured in credit cards, never again did Kaspi let customers’ WTP drop out of sight.

Making It Stick

Even in organizations whose culture is firmly centered on customer WTP, it is helpful to develop practices that periodically remind everyone of their firm’s focus. Think of it as the organizational equivalent of Post-it Notes on your refrigerator. It is not that you don’t know that your family needs a fresh carton of milk. But seeing that little pastel note on your fridge is a useful reminder nevertheless. At Harvard Business School, there is seldom a week—and rarely an important meeting—when no one mentions the mission of the school. It is not news to anyone, of course, and it can feel overly rehearsed. And yet, hearing the mission mentioned one more time, the conversation often takes on a different tone, as if by magic.

Amazon is well known for a set of practices that encourage the organization to think in terms of WTP. In Amazon meetings, there is always an empty chair. It is reserved for the customer, whom the meeting ostensibly serves.23 When Amazon managers build a new service, they begin by writing an internal press release that announces the launch of the (not-yet-existing) service.24 Take a look at the internal press release that Andy Jassy, CEO of AWS, wrote for Amazon’s S3 storage service.25 (This is Jassy’s 31st draft, by the way.)26

SEATTLE—(BUSINESS WIRE)—March 14, 2006—S3 Provides Application Programming Interface for Highly Scalable, Reliable, Low-Latency Storage at Very Low Costs

Amazon Web Services today announced “Amazon S3™,” a simple storage service that offers software developers a highly scalable, reliable, and low-latency data storage infrastructure at very low costs. Amazon S3 is available today at http://aws.amazon.com/s3.

Amazon S3 is storage for the Internet. It’s designed to make web-scale computing easier for developers. Amazon S3 provides a simple web services interface that can be used to store and retrieve any amount of data, at any time, from anywhere on the web. It gives any developer access to the same highly scalable, reliable, fast, inexpensive data storage infrastructure that Amazon uses to run its own global network of web sites. The service aims to maximize benefits of scale and to pass those benefits on to developers.

This practice—“working backwards” in Amazon-speak—encourages employees to determine a target audience first and then describe the appeal of the new service.27 This exercise forces them to use language that customers understand. Ian McAllister, a former general manager at the company, explains, “If the benefits listed don’t sound very interesting or exciting to customers, then perhaps they’re not (and [the product] shouldn’t be built). Instead, the product manager should keep iterating on the press release until they’ve come up with benefits that actually sound like benefits. Iterating on a press release is a lot less expensive than iterating on the product itself (and quicker!).”28

As this chapter illustrates, companies that center their strategy on WTP find a rich set of opportunities. The concept is so simple: increase the maximum amount that a customer would ever be willing to pay for your product. The resulting opportunities, however, are extraordinary. As you begin to use the value stick and WTP to formulate your company’s strategy, keep these considerations in mind.

- A sales-focused mindset risks ignoring opportunities to raise customer WTP. In a product-centric organization, you thrive when you increase transaction volume. Organizations that train their lens on WTP have a richer set of avenues to create value and are often more successful for exactly this reason.

- An obsession with business models—how you capture value—is particularly risky, because value capture is a zero-sum game: from the very beginning, you accept that your success makes customers worse off.

- Interdependence is the rule, not the exception. WTP, price, cost, and willingness-to-sell (WTS) are all connected. When you increase WTP, the other elements that make up the value stick will typically move as well. The WTP for Apple products is truly remarkable, but the company incurs extra cost to lift its WTP. Despite its value as a strategic guide, do not consider WTP in isolation. It is important to keep in mind the insight from chapter 3: the ultimate arbiter of strategic success is an increase in customer delight, not WTP per se.

- Leading need not mean winning. Because companies compete for business by offering greater customer delight, having the best quality in the market or being the most admired organization is no guarantee of success. Even companies with middling products can delight customers in extraordinary ways. The Toyota Corolla, one of the entries on my list of stellar product launches, is a good example. By all accounts, the Corolla, first built in 1966, was a modest vehicle. To increase its appeal and raise WTP, the Corolla’s designer, Tatsuo Hasegawa, provided drivers with splashes of excellence: separate bucket-type seats, a sporty floor-mounted gearshift, and aluminum headlight enclosures (figure 4-4).29 Yet in the late 1960s, no one would have placed the Corolla in a lineup of cool cars with high WTP. After all, who would drive a Corolla if you could race a Pontiac Bonneville? So how did the Corolla manage to outsell the Bonneville? Customer delight! At ¥432,000 ($1,200 in 1966, $9,560 in current dollars), the Corolla was a steal. When Corollas were introduced in America in the late 1960s, customers found them to be so simple and reliable that they quickly became a favorite among first-time buyers and middle-income Americans who purchased a second car.30 Toyota built its North American beachhead not by beating Detroit in terms of WTP; the company was second to none when it came to customer delight.

Figure 4-4 The 1966 Toyota Corolla (left) and the 1966 Pontiac Bonneville

- What do executives love best about customer delight? The fact that it is highly contagious. Just ask David Vélez, CEO of Brazil’s Nubank, the world’s largest independent digital bank. Nubank gains more than 40,000 customers each day, 80 percent of them through referrals from existing customers. “Nubank has not had to spend a dollar on customer acquisition,” says Vélez.31 When the neobank announced its credit card for Mexico in 2020, 30,000 people joined the wait-list. Nubank’s secret? “We want customers to love us fanatically.”32