Professor Michael Porter popularized the distinction between operational effectiveness and strategy. Strategic moves, he explains, confer a lasting competitive advantage. Operational effectiveness is important but not sufficient to achieve corporate success.1 After all, everybody strives to be operationally efficient; there is no lasting advantage in adopting modern management practices, because every company will use these techniques if they prove effective. Smart strategic moves create differences between companies. Investments in operational effectiveness reinforce similarities (figure 15-1).

Figure 15-1 Strategy versus operational effectiveness

Warren Buffett is credited with a story about a parade that nicely illustrates Professor Porter’s powerful idea: “One spectator, determined to get a better view, stands on his tiptoes. It works well initially until everyone else does the same. Then, the taxing effort of standing on your toes becomes necessary to be able to see anything at all. Now, not only is any advantage squandered, but we’re all worse off than we were when we first started.”2

Buffett’s story builds on two assumptions. The first is that standing on tiptoes will spread quickly; any initial advantage is fleeting. The second is that the effect of tiptoeing is similar for everyone. The spectators are all a few inches taller, but the differences in height remain roughly the same. Is investing in operational effectiveness really like standing on your tiptoes? Let’s find out. We first discuss the speed with which management practices spread.

The Speed of Diffusion

The view that you cannot achieve a lasting productivity advantage by adopting modern management techniques, it turns out, is too simple.3 More than a decade ago, Professors Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen assembled a research group to systematically study the diffusion of management practices. After more than 12,000 interviews at companies in over 30 countries, the verdict is in.4 My colleague Professor Raffaella Sadun, a prominent member of the group, explains the key finding: “If you look at our data, it’s obvious that core management practices can’t be taken for granted. There are enormous differences in how well managers execute even basic tasks like setting targets and tracking performance. And these differences matter: better-managed firms are at a long-term advantage; they are more productive, more profitable, and they grow at a faster pace.”5

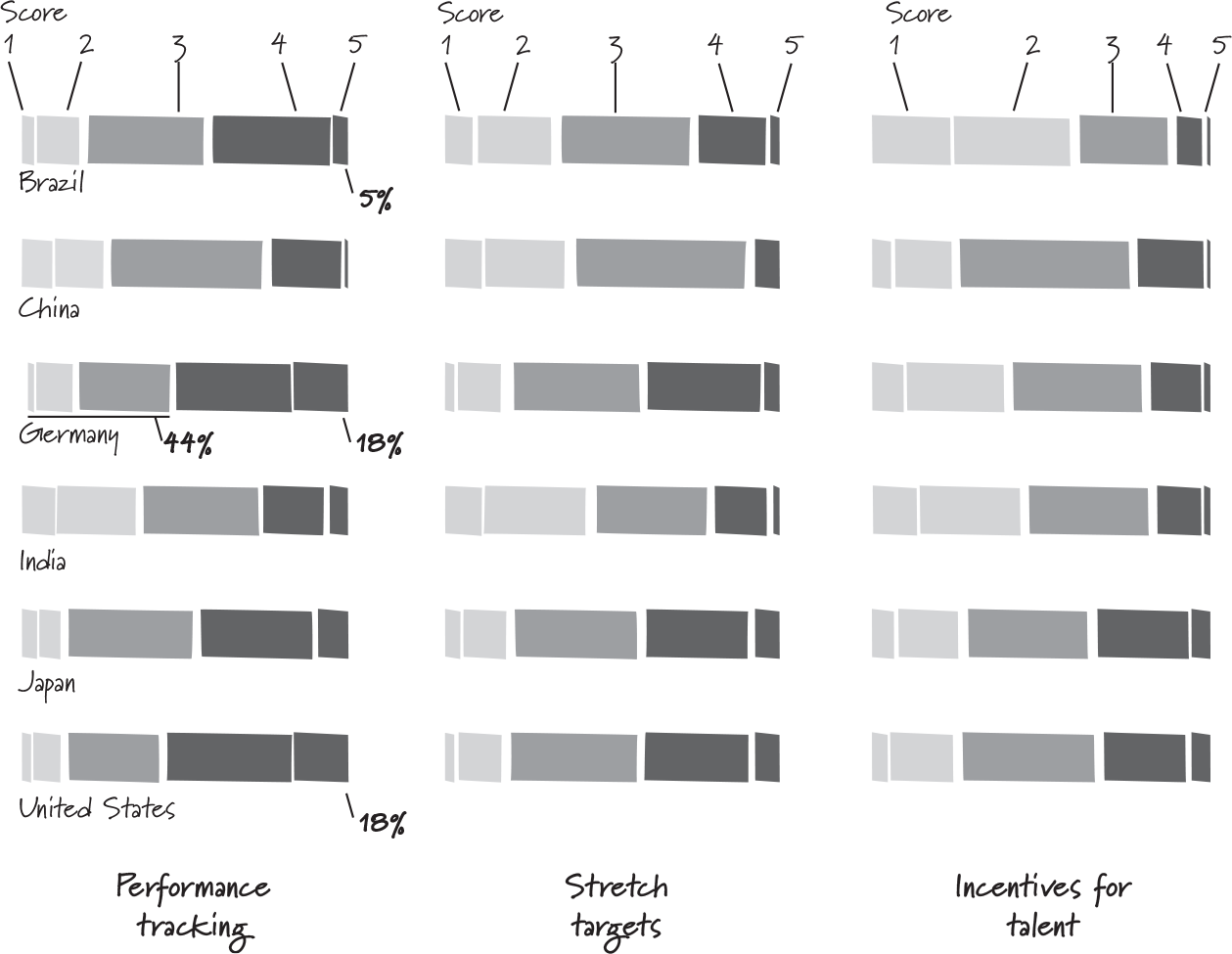

Figure 15-2 displays some of the differences in management quality.6 The left column shows whether companies regularly track their performance, on a scale from 1 (the company has no KPIs) to 5 (KPIs are frequently measured and well communicated throughout the organization).7 Some 18 percent of US companies are rated 5. In Brazil, only 5 percent of firms are top-ranked. Even more interesting than these international differences is the wide in-country dispersion.8 In Germany, only 2 percent of companies have no KPIs, but 44 percent are rated 3 or lower, meaning they still fall well short of best-practice performance tracking. Yet 18 percent of German companies are best in class.

Figure 15-2 Diffusion of management practices

This pattern—excellence and mediocrity living side by side—is repeated across dozens of management practices. The middle column of figure 15-2 illustrates the dispersion in target setting, and the right panel shows the extent to which companies use appraisals and incentives to motivate their employees.* The results are always the same. In similar competitive contexts, some companies are stellar while others are decidedly middling. Substantial differences in the adoption of modern management practices exist even across plants that belong to the same firm. Nothing about the diffusion of good management is automatic or fast.

An important question is whether these practices are applicable everywhere. Might the effectiveness of financial incentives depend on the type of work? Could it be that financial incentives are more broadly acceptable in, say, Anglo-Saxon cultures? There is little doubt that the performance consequences of adopting modern management practices vary from company to company.9 Even so, the effects of better management are so great that they are not easily swamped by external circumstances or company cultures. Consider this: moving a firm from the worst-managed 10 percent of companies to the best 10 percent increases productivity by 75 percent.10 These benefits of better management are remarkably similar across countries and cultures. The sheer size of the productivity advantage suggests that a vast majority of companies would benefit from better management.

You might wonder why so many firms fail to adopt core management practices if they have such significant payoffs. Three barriers seem to be particularly important.

- Knowing your company—Many managers find it difficult to assess the quality of management at their firms. Professor Sadun explains, “At the very end of our conversations with each of the companies, we always asked managers to tell us, on a scale from 1 to 10, how well their company is managed. The mean rating is a 7 on the 10-point scale, quite high, but the answers do not correlate with the actual adoption of modern work practices. Many executives do not seem to know the quality of their management.”11

- Managerial involvement—Some executives prefer a hands-on management style; they frequently visit plants and work one-on-one with employees and suppliers on operational tasks. Others focus on collaboration in the C-suite. There is no general performance advantage in adopting either style, but hands-on managers run the risk of seeing process-oriented management techniques as a substitute for their own personal involvement. As a result, these executives often fail to adopt some of the most effective tools, such as automated performance tracking and financial incentives.12

- Understanding the promise—Not seeing the likely performance consequences of better management is a final hurdle for companies to make the necessary investments. In most companies, the data suggest, improved execution is more valuable than many managers believe. As a result, the gulf between poorly managed firms and better-managed ones is likely to widen over time. Executives who do not believe in incentives, for instance, are unlikely to introduce them, robbing their firms of an essential instrument to encourage the adoption of proven management techniques.

Springboard for Strategy

Standing on tiptoes at a parade is self-defeating, not only because everyone will quickly imitate the move but also because the results do not vary much from one spectator to the next. Do companies that invest in operational effectiveness share this fate? Will they end up looking like everyone else?

Intel provides an interesting example. A leading producer of memory chips in the early days of Silicon Valley, the company had fallen behind its Japanese competitors by the mid-1980s.13 Japanese executives had pioneered practices such as total quality management and continuous improvement in the 1970s, outcompeting Intel with higher quality at lower cost. By any manufacturing metric one might consider—equipment utilization, yield, reliability, overall cost, and productivity—Intel’s performance was dismal compared to that of its Japanese rivals. Craig Barrett, Intel’s manufacturing czar at the time and future CEO, remembers, “We were unpredictable. We were not cost competitive. We were not manufacturing competitive, and the realization was that we needed to do things differently.”14

Intel aimed to slash costs by 50 percent in 1985 and by another 50 percent the following year. To reach these ambitious targets, the company shut down its least-efficient production facilities and let go nearly 5,000 workers. Managers at the remaining facilities were asked to upgrade their manufacturing practices dramatically, often copying the Japanese model. Like its Asian competitors, Intel removed all sources of contamination from its facilities and its supply chain, shifted the responsibility of maintaining production equipment to the suppliers of the equipment, and automated its fabrication units (“fabs”). It took Intel nearly a decade and billions of dollars in investment to remake its operations. By the early 1990s, however, the company’s productivity had quadrupled from the 1980s levels, utilization had surged from 20 percent to 60 percent, and yields improved from 50 percent to more than 80 percent. Intel emerged as a highly efficient, low-cost producer.15

A good number of Intel’s initiatives resemble standing on tiptoes. Closing inefficient plants and copying advanced manufacturing techniques raise a company’s financial performance, of course. But as Professor Porter and Buffett emphasize, these initiatives do not create the type of differentiation that is the basis for long-term competitive advantage.16 For Intel, however, copying Japanese practices was only act one. The company set out to imitate the modern management practices of the day, and in the process of doing so it discovered novel ways to reduce cost, increase speed, and raise quality.

One of Intel’s issues was that its developers created new processes directly on the manufacturing lines, working side by side with production staff. This approach resulted in fast transfers from development to fabrication, a key advantage for a company like Intel that competed on being first to introduce higher-capacity memory chips.17 But codeveloping processes had serious shortcomings as well. The approach led to low utilization—development and production teams frequently competed for access to equipment—and immature and unpredictable production.

As Intel pushed for parity with its Japanese competitors, it began to separate development and production. The 1-micron 386 microprocessor, for instance, was developed in Portland but produced in Albuquerque.18 Over time, the company became world class in moving technology from development to production and from one fab to another.19 It was able to ramp up production volumes without sacrificing quality. How might the company exploit this capability?

Intel made two game-changing strategic decisions. It ceded the market for memory chips, in which it had retained a small and unprofitable share, to its Japanese competitors. Important in the company’s early days, by the mid-1980s, speed counted for little in memory products. Instead, Intel concentrated on microprocessors, a market where its superior design capabilities coupled with manufacturing prowess held great promise.20 Much to the disbelief of its customers, Intel also decided to single-source its microprocessors, beginning with the 386 in 1985.21 This was unheard of in the semiconductor industry. Firms had always licensed their designs to rival companies, reassuring customers that they could meet demand. Intel’s decision to serve as the single source of its products critically depended on its improved manufacturing practices. Barrett remembers, “Intel got to the point where it could generate enough customer confidence to pull off [single-sourcing].… Our quality thrust of the early 80s began to pay off in improved consistency on the manufacturing line and overall better product quality.”

By pursuing operational effectiveness, Intel ended up gaining valuable strategic opportunities, single-sourcing being one of them. Intel is typical in this respect. Programs to raise operational effectiveness often provide the building blocks for strategic renewal.22 It is as if the spectators at the parade had gotten up on their toes and caught a glimpse of something new. They gained a different perspective and began to shift their position in response to it. Once it was fully mature, Intel’s technology transfer strategy, eventually dubbed “Copy EXACTLY!,” was no longer easy to replicate, because it required significant organizational and cultural adjustments. With Copy EXACTLY!, the company’s production engineers lost much of their autonomy. Intel’s Eugene Meieran recalls, “It was a huge cultural issue. Engineers would say, ‘I am an engineer. I want to make changes to the process. Why should I go through this bureaucratic morass [of having the smallest changes approved by senior managers]?’”23 Not surprisingly, some engineers were so unhappy that they left Intel.24

As organizations invest in operational effectiveness, it is of course possible that they end up performing the exact same set of activities as their competitors. But it is unlikely. Even if two companies embrace the same management approach—say, continuous improvement or high-powered incentives—their implementations will vary, and they will discover different avenues to raise willingness-to-pay (WTP) or lower willingness-to-sell (WTS). As a result, operational effectiveness can serve as a powerful springboard to strategic renewal.

Thinking about the role of operational effectiveness in explaining differences in productivity across companies, I take away a few insights.

- Good management practices and operational effectiveness help create meaningful differentiation between companies. They are hard to achieve, diffuse slowly, and can serve as the basis of a long-term competitive advantage.

- As Intel’s experience shows, operational effectiveness and strategy are intertwined. My advice is to pay little attention to the distinction. Do not dismiss an initiative simply because it seems to be an investment in operational effectiveness. It might well turn out to be the catalyst for a strategic renewal.

- Rather than asking whether projects fall in the “strategy” or in the “operational effectiveness” bucket, consider their potential to raise WTP or lower WTS. If an initiative is implemented successfully, how easy will it be for your competitors to imitate it? If a project moves the needle and is difficult to replicate, it will improve your firm’s competitive standing and raise profitability, whether or not the project is a clever strategic move or an attempt to improve operational effectiveness.

- There is no doubt that improving the quality of management can create substantial value. Keep in mind, however, that better execution is no substitute for sound strategy. Maxims such as “execution beats strategy every time” and “culture eats strategy for breakfast” are nonsense. The flawless implementation of an initiative that does not change WTP or WTS will fail to create value.