For the past decade, I have served as faculty chair of the Senior Executive Program for China, a flagship HBS program for Chinese managers. In this role I visit China often, and I am used to seeing dramatic changes from one visit to the next. Nevertheless, a recent experience in Shanghai left me dumbfounded. I love dumplings—who doesn’t?—and I make it a point to find restaurants that specialize in this delicacy. On this trip, I found just my kind of spot not too far from Hongqiao train station: a few tables, rickety chairs, and the most delicious dumplings in this part of the universe. At the end of the meal, I handed the cashier my credit card. She shook her head and said the restaurant did not accept cards. I should have known, of course. Not many small establishments do. I apologized and gave her a 50-yuan bill, only to be rejected again: “No card, no cash,” she said and pointed to a QR code displayed at the top of the apparently defunct register. “We only take Alipay or WeChat Pay.”

The restaurant, it turned out, had gone cashless. And it is not alone. Everywhere in China, cash is falling out of favor faster than you can say, “Check, please.” How did this happen? Card-based transactions, it seemed to me, had just gained prominence. And now, a minute-and-a-half later, cash was dead? Supplanted entirely by mobile payments?

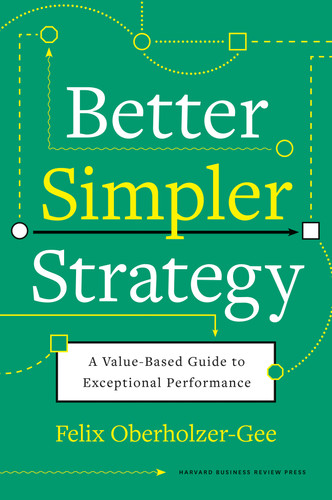

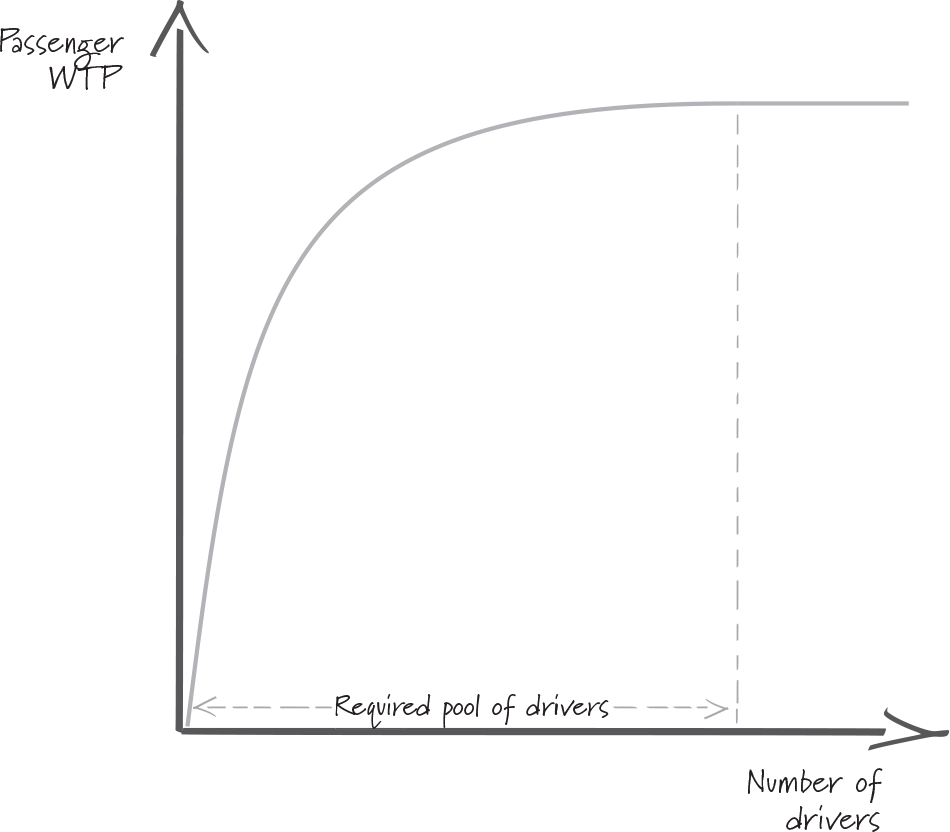

Rapid changes such as this one are emblematic of markets that have strong network effects. In these markets, customer willingness-to-pay (WTP) for a product or service (or even the use of money) rises as the adoption of the product or service increases (figure 8-1). At the outset, it is challenging to convince restaurants to accept mobile payments because few customers use the service. Similarly, customers are reluctant to install Alipay on their devices because few stores accept it. As adoption increases, however, the WTP of stores and restaurants grows. And as more establishments accept mobile payments, the number of customers who use these applications rises quickly.

Figure 8-1 Network effects: Adoption increases WTP

Network effects are a positive feedback loop: as more retailers attract a larger number of customers, additional retailers are drawn in. Network effects can cause markets to reach a tipping point: to spring from very low adoption to universal acceptance in no time at all. And the reverse is true as well. As fewer people use cash, the number of establishments that can make change drops and fewer stores are willing to accept cash. This situation gives customers an incentive to move to mobile payments.

China and other countries—Sweden, for example—are well on their way to becoming cashless societies. In 2010, mobile payment services were not on the top ten list of apps in China. Only a decade later, three-quarters of the Chinese population prefers mobile payments to cash.1 When Alibaba opened its futuristic supermarket, Hema, a few years ago, cash registers were not featured as part of the design. The People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, now has to intervene to protect the use of cash. The authorities regularly crack down on the hundreds of retailers that have stopped accepting cash.2 If history is any guide, the central bank faces an uphill battle. Network effects move WTP in a powerful fashion.

(Are you wondering how I solved my dumpling problem? While I was not able to pay for the meal, it turned out that the restaurant’s employees were happy to accept the price of the dumplings as tips—in cash!)

Three Flavors

It is useful to distinguish three types of network effects. They all raise WTP as adoption of a product increases, but the mechanism by which this occurs differs.

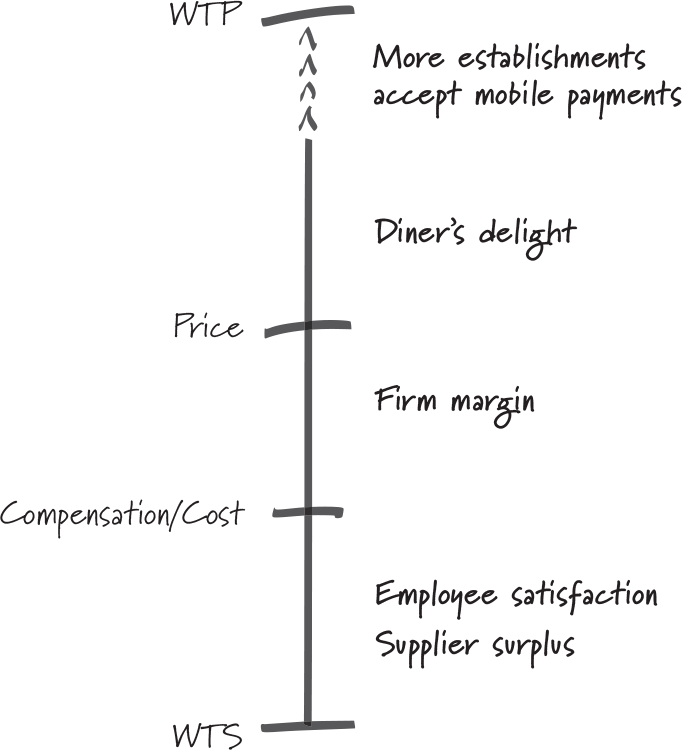

Direct network effects increase WTP whenever additional customers purchase a product (figure 8-2a). Any communication device is a good example. Think of the very first person who bought a fax machine. The device had no value; there was no one with whom to exchange fax messages. As the machines proliferated, the WTP for fax machines increased with the number of businesses and individuals who owned one. Think of a product you own. Would it become more useful or valuable if a larger number of people had that same product? If the answer is yes, there is a direct network effect.

Figure 8-2a Direct network effect

Indirect network effects raise customer WTP with the help of a complement (figure 8-2b). Game consoles and games, cars and repair shops, and smartphones and applications are all examples of markets with indirect network effects. As more customers purchase smartphones, developers will create more apps. And the availability of a greater number of useful apps raises the WTP for smartphones, thereby attracting additional customers. Indirect network effects often create chicken-and-egg dynamics. If we had more charging stations, more people would drive electric cars. But we lack charging stations because so few people own electric vehicles. To break the impasse, companies often invest in complements that have limited demand, hoping to spur indirect network effects.

Figure 8-2b Indirect network effect

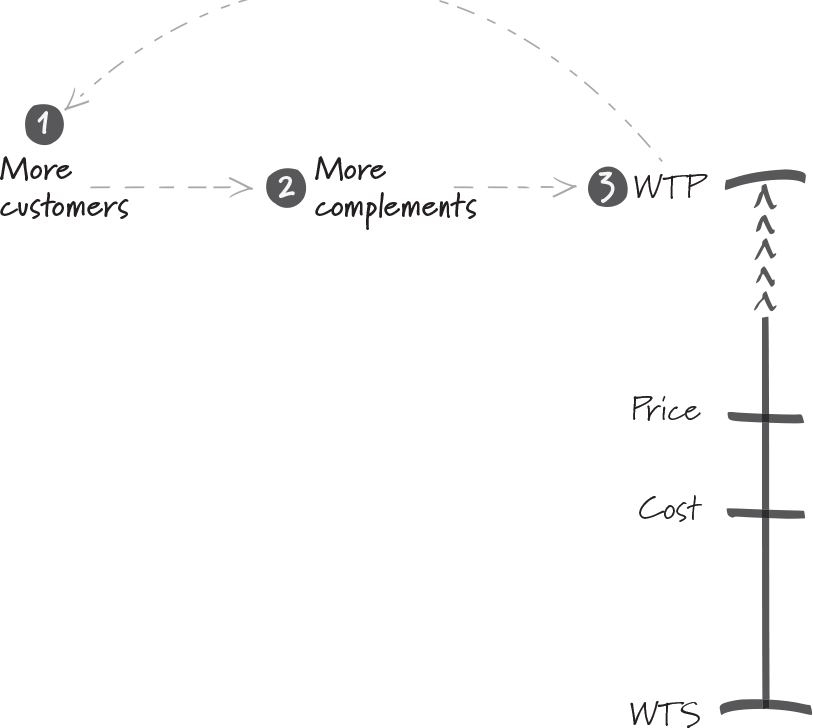

The third type of network effect is characteristic of platform businesses (see figure 8-2c). These companies attract more than one type of customer (or supplier), and WTP increases for one group as the other grows larger. Think of online travel agencies. Hotels find it more advantageous to list their properties on Expedia as more people book on the platform, and having a choice among a greater number of hotels draws additional customers. Many businesses create value by bringing together different types of customers. The New York Times, for instance, attracts readers and advertisers. Uber matches passengers and drivers. Amazon’s marketplace appeals to shoppers and merchants. In each of these cases, the WTP of one group of customers (advertisers, drivers, merchants) increases as the other group (readers, passengers, shoppers) grows in size.

Figure 8-2c Platform network effect

In this chapter, we will explore how network effects contribute to outsized business success, how they can lead to dramatic failures, and how they contribute to the creation of an economy that is increasingly dominated by very large (and exceptionally profitable) companies.

Sometimes, Winners Take All

Fifteen years after its founding, Facebook dominates social media. With 2.4 billion monthly active users, the company is the leading social network in more than 90 percent of all countries. Its share of social media page views is 50 percent in the United States, 70 percent in Africa, and 80 percent in Asia*, Europe, and South America.3 While successful historically, the company is now under enormous competitive and political pressure. Younger users flock to Snapchat and TikTok; Pinterest is gaining stature in e-commerce; and Amazon has started competing with Facebook for advertising dollars. To make matters worse, data and privacy scandals have nurtured cynicism about the organization’s motives and leadership. Facebook is now the least trusted among US social networks.4 Politicians and regulators speak openly about ways to break up the company.

How well is Facebook doing in these times of extraordinary challenges? Its performance is stellar. The company added more than 100 million users in 2019, 1 million of those in the mature US market alone. The same year, revenue rose by 29 percent, and shares were up by more than 50 percent.5 What explains this extraordinary staying power? Shouldn’t Facebook have fallen apart?

Facebook’s performance is testament to the remarkable power of network effects. The company benefits from all three types. As Facebook adds users, joining the network to socialize with friends and acquaintances becomes more attractive (direct network effect); brands and users have greater incentives to create and post content (indirect network effect); and the site becomes more desirable for advertisers (platform network effect). It is true that the tired-looking design and the loss of user trust have lowered WTP.6 At the same time, network effects lock in the company’s market position, and they keep WTP more than competitive with other social media.

At their most powerful, network effects provide formidable advantages, and markets tip in favor of a few companies. Google and Baidu (in search), Amazon and Alibaba (in e-commerce), Sony and Microsoft (in game consoles), Verizon and AT&T (in mobile services), and Visa and Mastercard (in credit cards): every one of these companies benefits from significant network effects.

The Geography of Network Effects

One of my morning rituals is to check my messaging apps. I usually begin with text messages, continue with WhatsApp, quickly check WeChat, and end with LINE. I had to install all these apps because network effects are often regional or even local in nature. WhatsApp is by far the largest messaging app globally, but it is close to useless in Japan, where LINE is leading. In China, everybody with a phone is on WeChat. If I had acquaintances in Ethiopia, Iran, South Korea, Uzbekistan, or Vietnam, I would need to install Viber, Telegram, Kakao, imo, and Zalo, the leading messaging apps in those countries.7

The strength of network effects depends on the number of users, but the relevant number is rarely the global one. Think of a company like Uber. Platform network effects play in its favor. Passengers benefit if the number of drivers increases, and drivers are more likely to join Uber if there are more passengers. But for Uber, the relevant number of users is entirely local. If I order an Uber in Boston, a larger number of drivers in San Francisco does not change my WTP.

The geography of network effects limits the attractiveness of many large platforms. Uber has 3 million drivers globally, but the company needs to start from scratch when it enters a new market, almost as if its business elsewhere did not exist. The result is a patchwork of local champions. Uber leads in the United States, DiDi dominates China, Gojek is ahead in Indonesia, and BlaBlaCar is number one in Germany. Regional network effects still produce powerful first-mover advantages. Once DiDi pulled ahead in China, that market tipped and Uber stood no chance. But Uber’s defeat in China had little effect on its standing in other markets.

Local Competition

How many different ride-sharing apps do you use? If I had to guess, I would say more than one. If you live in San Francisco, you probably have apps for Uber and Lyft. If Jakarta is home, I would guess you use Gojek and Grab. In Seoul, I would expect to see Kakao, TMap, and perhaps even TADA. Not only do network effects rarely lead to Facebook-style global dominance, even at the local level, winner-take-all outcomes are the exception. Different platforms often compete side by side. How many companies can survive in a local market? For example, what are the chances that Poolus, the fourth-positioned ride-sharing company in Seoul, will be a sustainable business?

To get a sense of how competitive a market will be, it is helpful to be specific about the mechanism by which network effects raise WTP. From a passenger’s perspective, arguably the most important benefit is proximity.8 A service with more drivers can offer shorter wait times (figure 8-3).

Figure 8-3 Competition in ride-sharing services

As wait times fall, the incremental benefit to passengers gets progressively smaller. Few people care whether their car arrives in a minute or in 30 seconds. To be competitive in wait times, a service needs to have the number of drivers indicated by the dashed line in figure 8-3. If Seoul is sufficiently large to allow four companies to each assemble this required pool of drivers, Poolus can survive. If only a single company can assemble the required pool, the local market is winner-take-all.

I hear you objecting—and you are correct, of course. What I just said is not quite right. One complication is that adding drivers to a market will have three effects, not one: as passenger wait times fall, more passengers will use ride-sharing services, because they like the shorter wait times, and, for a given number of passengers, drivers will have to wait longer. If the latter effect dominates, the market will never be able to reach the maximum passenger WTP shown in figure 8-3 because drivers exit as their wait times increase. A further complication is that ride-sharing companies typically treat drivers as independent contractors, not employees. This saves cost, but it also allows drivers to work for multiple ride-sharing organizations. In effect, a new entrant will not have to assemble a new pool of drivers. The entrepreneur can simply “borrow” the drivers already in the pool. This makes ride sharing far more competitive. Are you surprised that companies like Uber find it so difficult to reach profitability?

Ride sharing teaches a critical lesson. It is wonderful to know that your business benefits from network effects. It is even more important, however, to have a thorough understanding of how the number of customers will influence WTP. Knowing the mechanism by which adoption raises WTP helps you assess how competitive a market will be.

Let’s look at e-commerce platforms as another example. Clearly, people love shopping online. With a bit of work, you can always find a good deal. If lower prices are the key to the customer’s heart, e-commerce will be highly competitive. In figure 8-4, the line labeled “Low prices” shows how customer delight changes as an e-commerce business adds vendors. Initially, customer satisfaction rises because there is more price competition. The incremental effect wears off quickly, though. You only need a handful of vendors to be price competitive.

Figure 8-4 Competition in e-commerce

Fortunately, customers are not exclusively concerned about low prices. Many also care about a great selection. Amazon and Taobao lead in their respective markets, in good part because they offer unprecedented variety. If selection is critical because customers like the idea of one-stop shopping, e-commerce sites need a far greater number of stores to be competitive in customer delight, and winner-take-most outcomes are more likely. Amazon’s market share in US e-commerce stands at more than 50 percent. Tmall’s share in China is even greater.

Similar dynamics are at play at Rappi, a Colombian instant-delivery startup that competes heavily on its broad scope of services. In addition to delivering meals and groceries, Rappitenderos make ATM visits, walk your dog, stand in as the 11th player in a soccer match, purchase your concert tickets, and exchange, in person, the oversized shirt you bought on Zara.com. Rappi’s model builds network effects that benefit workers (who fear being idle) and customers (who greatly value the near-instant provision of an extraordinary selection of services).

In all these examples, it is key to think about the incremental customer delight and supplier surplus that is created as you broaden the scope of platform services. Do you really strengthen your network effects—even at your current scale?

The Price of Exclusivity

It was to be the most memorable welcome-back party ever. In the summer of 1997, thousands of Apple loyalists traveled to MacWorld Boston to celebrate the return of their hero, Steve Jobs. Forced in 1985 to resign from the company he had cofounded, Jobs had returned to Apple earlier that year. He found a company in shambles. Low on cash and short on a vision for its future, Apple was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.9 Mary Meeker and Gillian Munson, then analysts at Morgan Stanley, summarized the firm’s dire prospects at the time: “Apple, in our view, is a deeply troubled company—revenue has declined between 15 percent and 32 percent year-to-year in each of the last six quarters.… Using medical analogies, we have written this patient off as dead.”10 Newspapers and magazines feverishly followed the steep decline and widely anticipated the failure of the world-renowned company (figure 8-5).11

Figure 8-5 Apple’s touch with failure

The crowd in Boston’s convention center was giddy with expectation. What announcement would Jobs make? What surprise did he have in store for them?

Jobs did not disappoint. In fact, his surprise was bigger and more profound than his audience had anticipated: “Apple lives in an ecosystem, and it needs help from partners,” Jobs explained. “I’d like to announce one of our first partnerships today, a very meaningful one, and that is …” The screen behind Jobs lit up, and the stunned crowd saw—Bill Gates! Jobs announced a collaboration with Microsoft, Apple’s archrival, its despised, decidedly uncool (and wickedly successful) nemesis.12

How had it come to this moment? How had Apple, the most profitable computer company of the 1980s, sunk so low? Direct and indirect network effects are an important part of the story. Throughout the 1990s, customer WTP for Microsoft’s Windows operating system increased as adoption, fueled by the low prices of PCs, grew rapidly. Thanks to the growing number of Windows users, it was easier to exchange documents and ask for help with pesky software. Even more important than this direct network effect was an indirect effect: the incentive to develop, maintain, and update software written for Windows.

In the early history of computers Apple had been a force to be reckoned with. Its global market share stood at 16 percent in 1980, but that changed with the subsequent onslaught of significantly less expensive PCs built on Windows software and Intel microprocessors. By the time Jobs returned to the company in 1985, the difference in scale was astounding. That year, Intel shipped 76 million processors, and Microsoft had an installed base of nearly 350 million machines. Apple, on the other hand, shipped fewer than 5 million units, and its installed base was a mere 10 percent of Microsoft’s.13 Suppose you were a developer with a great idea for a novel type of software. Would you write for Windows, or for Apple? As Jobs explained in 1996, “The key is to convince developers of innovative new software products that they can make those products run best or only on your operating system.”14 By the summer of 1997, Apple had lost this ability.

A key element of Apple’s collaboration with Microsoft was Gates’s promise to continue developing Office—the popular suite of productivity software—for the Mac platform. In the past, Microsoft’s releases of the Mac version of Office had been sporadic, which led many Apple customers to switch to Windows. Now Gates promised timely releases, the same number of Office versions for PCs and Macs, and, better still, features that would exploit the unique capabilities of Apple’s OS.15

Apple’s brush with bankruptcy illustrates the dual role of premium prices. They generate a sense of exclusivity and enviable margins, and they keep the number of customers limited. Such niche strategies can be highly successful and sustainable in the long term, think of Porsche or Hermès, for example. In markets with strong indirect network effects, however, premium prices reduce the incentives of companies to provide the very ingredient for business success: complements. In this environment, premium prices are difficult to sustain. In fact, they cost Apple the chance to be the leading player in personal computing.*

Apple’s difficulties reflected more than a lack of compelling software, of course. The 1995 product shortages, a poorly designed licensing program, the confusing reorganization of the marketing function, and miserable inventory management all conspired to weaken the company.16 Add competitors with powerful network effects, however, and the company was in serious trouble. Jobs remembered that Gil Amelio, a former CEO of Apple, was fond of saying, “Apple is like a ship with a hole in the bottom leaking water.”17 That hole was the missing network effects. Sadly, Amelio thought his job was “to point the ship in the right direction.” How could he have left the hole unplugged?

Fast-Forward

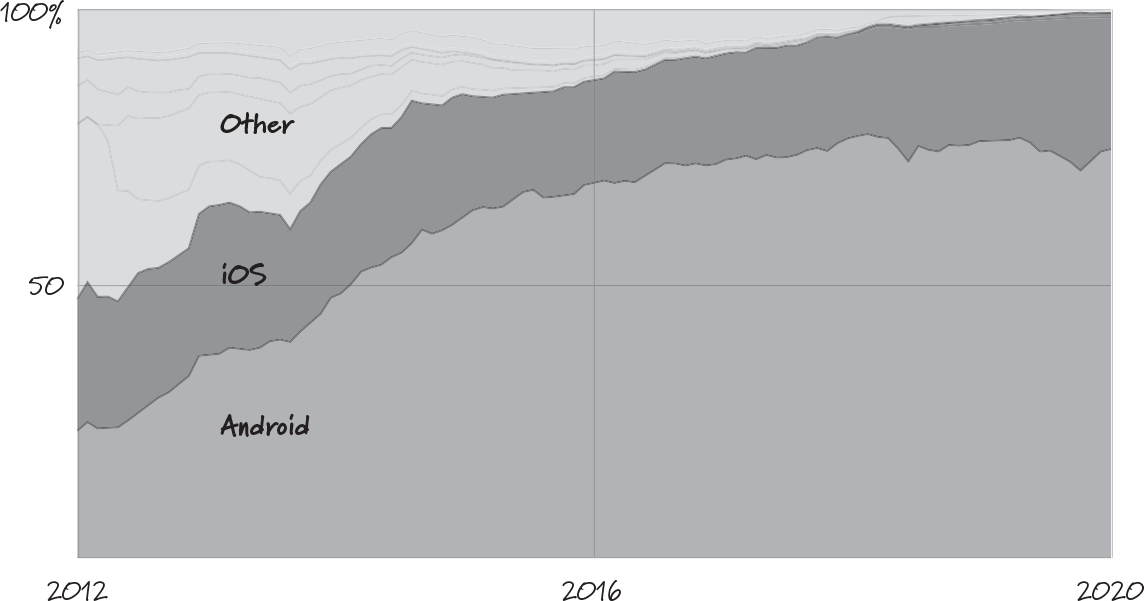

It is interesting to apply the lessons of 1997 to Apple’s current situation. Figure 8-6 shows the company’s market share in mobile operating systems.18 Is Apple in trouble once again?

Figure 8-6 Global market share of mobile operating systems

It is easy to see that same scenario. The company sells expensive phones, and it generates a precious sense of exclusivity. Meanwhile, the competing platform, Google’s Android, is the default operating system on less-expensive devices that dominate the global market. Isn’t this a replay of the 1980s and 1990s? Is Android the new Windows?

There are indeed similarities. Operating systems with a small number of users are unsustainable. Windows phones, for example, never caught on, and Microsoft abandoned its mobile phone platform in 2020. Microsoft’s failure in phones, however, was not due to network effects. These do not play a significant role in this market because users can easily connect with one another irrespective of their mobile operating systems. Moreover, the same mobile phone applications are available on every platform, because developing apps tends to be far less expensive than developing the feature-rich software for personal computers.19 Even Microsoft, with its minuscule market share, had an app store that boasted more than 500,000 products.20

For Apple, the key question is whether complementors will continue to develop products and services for an operating system with a 20 percent market share. If complements are not too expensive to produce, the answer is yes, and Apple will thrive. If complements require significant and perhaps country-specific investments, however, Apple will come under pressure in countries like Indonesia, where its market share has fallen to less than 6 percent. The moment technology evolves to include expensive integrations of phones and complements—think of applications in financial services, transportation, and health—developers will again give preference to the operating system with the largest number of users, Android in this instance. While no one knows the trajectory of technology, understanding how the cost of developing complements can elevate or diminish the importance of network effects is a critical skill that every strategist needs in their toolbox.

The Savvy Strategist—Imaginative and Vigilant

Managing in environments that have strong network effects is challenging because the feedback loops accelerate change: seemingly in the blink of an eye, cash disappears; platforms like TikTok, an entertainment app, and Pinduoduo, an e-commerce business, gain hundreds of millions of users almost overnight. In other instances, network effects impede change: they give rise to a stable set of platforms that dominate their industries decade after decade. Network effects create turbulence and intransigence; they generate vast opportunities for change and nearly immutable competitive outcomes. What mindset should you adopt in this type of environment? I argue that imagination and vigilance are two of the most important traits.

Imagination

A common view is that industries either have network effects or they don’t. This mindset is too narrow. Many companies gain advantage by creating network effects where none existed. Others succeed by making existing effects much more powerful. Apple’s FaceTime service created new network effects for customers who owned iPhones and iPads. UberPool added network effects between passengers who want to travel to similar destinations.

As you think about ways to lift your customers’ WTP with the help of network effects, do not focus on the current state of your industry. Don’t pay attention to whether or not your company benefits from network effects at this time. Instead, think of someone who owns one of your products. How might they benefit if others adopted that same product? Let your imagination fly.

Vigilance

Even if your firm lacks opportunities to create network effects, other companies might succeed at building them. Because network effects create a significant first-mover advantage, it is critical that you spot budding networks and up-and-coming platforms early. Pay close attention not only to rival companies but also to suppliers. The latter, recent business history shows, can become particularly powerful. Online platforms are a fairly recent phenomenon in many supply chains. But once they are established, they are difficult to displace, and they are likely to help themselves to a significant share of your profits. OpenTable, the leading restaurant-reservation service in the United States, is a good example. The platform charges restaurants a fixed monthly fee and a commission for each reservation.21 In an industry where profit margins often hover below 5 percent, an OpenTable reservation can cost an establishment as much as 40 percent of its net profit.*, 22

Yet restaurants have little choice. For many diners, an establishment that is not listed on OpenTable simply does not exist. Competing platforms such as Resy, Reserve, and Tock, all of which entered the market in the early 2000s, have found little success. “When only ten other restaurants are on Resy, you don’t want to be the one to take the plunge and possibly lose revenue,” says Dallas restaurateur Brooks Anderson. “OpenTable is as ubiquitous as Coca-Cola.… People are afraid to make the switch.”23 Restaurateurs learned a hard lesson. What is rational individually—everybody wants to be on the largest platform—creates significant challenges for the industry as a whole. Allowing one platform to become dominant is a grave strategic mistake.

I find it interesting to see how many network effects we now take for granted. Remember when searching for information required a trip to the library? Finding high school classmates involved thumbing through yearbooks and telephone directories? Estimating traffic was an art, not a science? How we trekked from store to store to find the products we wanted to purchase? Network effects underpin many of the businesses that have had such an impact on the way we live and work today. Technology made these advances feasible, but network effects are the reason these businesses were actually built and why they attracted the talent and the capital that allowed them to offer their services at scale.

As I think about network effects, a few insights stand out for me.

- Network effects increase WTP by connecting users directly, through complements or via platforms. Companies that build network effects raise WTP and they limit competition at the same time.

- Market share is an inadequate predictor of profitability. It should never be used as a strategic goal. Markets with network effects, however, are an exception. They reward companies with more users and greater share.

- Facebook-style winner-take-all outcomes are rare. Interestingly, geography both limits and enhances the strategic value of network effects. If these are local in nature, different companies win in different markets. But if the markets are small enough, they are more likely to tip and create a single winner. The net result is a patchwork of local champions.

The dark side of network effects is the extent to which they limit competition. The question of whether companies like Facebook, Google, and Alibaba have become “too big” is hotly contested.24 To resolve the issue, we need to weigh the customer delight that results from network effects against the cost of limited competition. This is not a new question, of course. The regulation of natural monopolies—companies, such as railways and utilities, that benefit from scale to such an extent that no one is able to compete—involves similar trade-offs, with one important difference. While the monopolies of yore used their market power to raise prices and shrink customer delight, the opposite is more typical now. Do the low prices limit competition and innovation to such an extent that we would be better off forgoing some of the immediate benefits of network effects? We do not know.